LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• demonstrate knowledge of statistics and vulnerability factors relating to suicide and self-harm across the lifespan

• understand the impact of rape and sexual assault on risk to self

• implement risk assessments and manage risk in the context of a sexual assault referral centre.

Risk identification and management are core components in many clinical settings. It is well established that risk is not preventable. However, best practice involves making decisions on the basis of knowledge – of the research evidence, of the patient and their social context and of the patient's own experience – and clinical judgement. Sexual assault referral centres (SARCs) are one such setting where these principles are crucial in terms of understanding the epidemiology and applying research regarding risk assessment and management. This article in part applies this knowledge to the SARC setting but is also highly relevant and applicable to other settings.

SARCs provide 24/7 support to people who have experienced recent and non-recent rape and sexual assault. Effective care within the context of a SARC involves addressing both the mental and physical healthcare needs of patients. It is therefore paramount that SARC practitioners providing support to patients are appropriately trained and competent in carrying out risk assessments and devising appropriate plans for risk management. A multidisciplinary approach is also crucial when it comes to effective risk management. Risk assessment and management is a continuous and dynamic decision-making process (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2016). There is an extensive literature detailing the increased risk of psychiatric disorders, self-harm and suicide following sexual assault (e.g. Burnam Reference Bryan and Rudd1988; Hanson Reference Gould, Fisher and Parides1995; Kessler Reference Heke, Forster and d'Ardenne1995; Borja Reference Borja, Callahan and Long2006; Littleton Reference Khadr, Clarke and Wellings2010; Jonas 2011). In England, it is estimated that approximately 40% of individuals presenting to SARCs have a pre-existing mental health problem (Brooker 2015), which suggests that those attending a SARC already present with some vulnerabilities. In addition to risk identification and management being part of the professional duty of every SARC practitioner, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Reference Littleton2012) also stresses the importance of conducting an assessment of patients’ risk and needs. The World Health Organization (World Health Organization 2014: p. 4) states that ‘early identification and effective management [of risk] are key to ensuring that people receive the care they need’.

This article is an attempt to summarise key areas of information and guidance in relation to risk assessment and management within the context of SARCs across the lifespan. Although the article applies much of its content to the SARC context, it may be of interest and value to professionals working in other fields.

For the sake of brevity, we will use the term ‘child sexual abuse’ to refer to sexual violence, abuse or exploitation in relation to children and young people. Similarly, ‘sexual assault’ will refer to both sexual assault and rape.

Sexual offences: UK statistics

Prevalence in the adult population

Although sexual assault is widespread and represents a major public health concern in the UK, given the wide range of mental and physical health problems associated with it, it remains largely underreported (Macdowall Reference Kilpatrick, Veronen, Best and Figley2013). The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW; Office for National Statistics 2020) noted that 154 113 sexual offences against individuals aged 16–59 years were recorded by the police in England and Wales in the year ending March 2020, showing little change from the previous year (154 213). According to the CSEW (Office for National Statistics 2020), estimates for the year ending March 2020 showed that 2.2% of individuals aged 16 to 59 years had experienced sexual assault. The year ending March 2020 was the first year since 2012 with no increase in the number of sexual assaults, and the offence of rape was also seen to fall marginally from 55 771 to 55 130 offences for the same time period.

Prevalence of child sexual abuse among children and young people

The National Crime Survey (Office for National Statistics 2016), which reports on UK population survey data rather than crimes officially reported to police, highlighted some important characteristics of child sexual abuse. It estimated that such abuse had been experienced by 11% of girls and 3% of boys. Furthermore, of these, 27 and 3% respectively were later sexually assaulted as adults. Between 12 and 14% of people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (transgender, transsexual) (LGBT+) reported having experienced child sexual abuse. The abuse began quite early, with 27% of respondents having been abused by 6 years of age and 53% by age 9. In the year ending March 2019 (Office for National Statistics 2020), the police recorded 73 260 sexual offences against children, and around one-quarter (27%) of these were rape offences. Most children do not disclose abuse at the time it occurs but may disclose in later years, if at all. It is important to note that the definition of child sexual abuse within this survey applied only to incidents involving penetration, and these figures are therefore likely an underestimate of the scale of the problem.

Suicide: definitions and statistics

Most practitioners report feelings of anxiety when working with individuals who report suicidal ideation and/or intent and, from our own clinical experience, it is not uncommon for some practitioners to either overreact or underreact to the disclosure of suicidal thoughts by patients. It is therefore important to differentiate terminologies used in routine clinical practice, as different behaviours related to risk to self are likely to result in different management pathways. Box 1 offers definitions of the most commonly used terms.

BOX 1 Suicide-related terms commonly used in clinical practice

Suicidal behaviour: Thoughts and behaviours related to suicide and self-harm that do not have a fatal outcome. Suicidal behaviours include suicidal ideation, suicide plans and suicide attempts.

Self-harm: Intentional self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of motive.

Suicide plan: The formulation of a specific action by a person to end their life.

Suicide attempt: Engagement in a potentially self-injurious behaviour in which there is at least some intention of dying as a result of the behaviour.

Suicide: The act of intentionally ending one's own life.

(O'Carroll Reference Muehlenkamp and Gutierrez1996; Silverman Reference Quinlivan, Cooper and Meehan2007a, Reference Rajalin, Hirvikoski and Jokinen2007b; Nock Reference Nock, Borges and Bromet2008; NICE Reference Kõlves and De Leo2011; British Psychological Society Reference Silverman, Berman and Sanddal2017)

Suicide statistics for the adult population

Suicide is the 14th leading cause of death worldwide, responsible for 1.5% of all mortality (O'Connor 2014) and it is the leading cause of death among young and middle-aged men in the UK (Office for National Statistics Reference Nock, Borges and Bromet2015). Suicide is therefore a major public health concern, with the World Health Organization (2014, p. 3) stating that every 40 s a person dies by suicide somewhere in the world, with many more attempting suicide. As regards UK statistics, 6507 people died by suicide in 2018, compared with 5821 in 2017, representing the first increase in deaths since 2013 (Office for National Statistics 2019). The latest report on suicides registered in 2018 in the UK by the Office for National Statistics (2019) reported a male suicide rate of 17.2 deaths per 100 000, representing an increase from the rate in 2017, but the female suicide rate of 5.4 deaths per 100 000 has remained consistent with the rates over the past decade (Office for National Statistics 2019). In 2018, Scotland was reported to have the highest suicide rate in Great Britain with 16.1 deaths per 100 000 persons (784 deaths), followed by Wales with a rate of 12.8 per 100 000 (349 deaths) and England the lowest with 10.3 deaths per 100 000 (5021 deaths) (Office for National Statistics 2019).

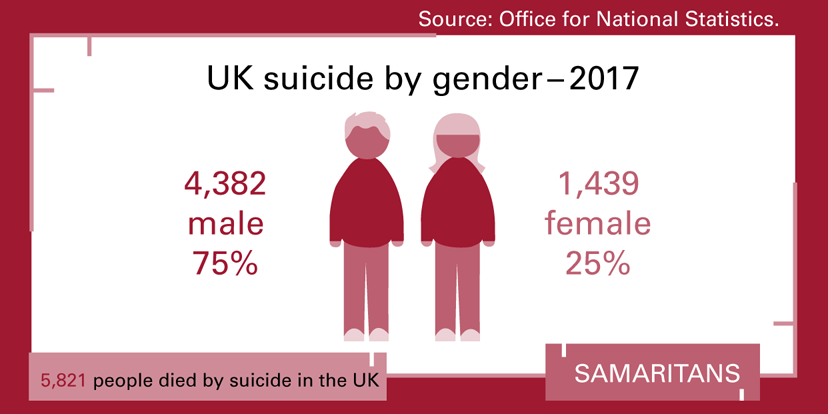

Among men, those aged 45–49 years presented the highest suicide rate, at 27.1 per 100 000 males and among women, those also aged 45–49 years had the highest rate, at 9.2 deaths per 100 000 females (Office for National Statistics 2019). Of note, death rates among the under 25s have generally increased in recent years, particularly 10- to 24-year-old females, where the rate has reached its highest level with 3.3 deaths per 100 000 females in 2018 (Office for National Statistics 2019). There has been a slight change in the male age groups that are more likely to die by suicide in the UK in recent decades: from 1991 until 2011, the highest age-specific male suicide rates were among men aged 30–44 years, whereas since 2013, men aged 45–59 years have had the highest rates, with 21.8 deaths per 100 000 population in 2017 (Office for National Statistics Reference O'Connor, O'Connnor, Platt and Gordon2018). This change in trend is thought to be linked to middle-aged men being more likely affected in recent years by economic adversity, alcoholism and social isolation (Samaritans 2018). The most common method of suicide for both men and women is by hanging, suffocation or strangulation, which account for 59.7% of all suicides among men and 42.1% among women (Office for National Statistics Reference O'Connor, O'Connnor, Platt and Gordon2018). The second most common method of suicide is poisoning, accounting for 18.2% of all suicides among men and 38.3% among women (Office for National Statistics 2018). Figure 1 illustrates UK suicide rates by gender in 2017.

FIG 1 UK suicide by gender in 2017 (data from Simms et al (2019); infographic created for the Samaritans and reproduced here with the permission of Jenni Munro, Samaritans Training Events Coordinator on behalf of the Samaritans research team).

Risk and protective factors for suicide in the adult population are discussed below (in the section ‘Identifying and assessing risk and protective factors’).

Suicide and risk of self-harm in children and young people

Rates of suicide in England and Wales have increased among adolescents by approximately 7.9% each year between 2010 and 2017 (Bould Reference Bould, Mars and Moran2019). There were gender differences, with suicide increasing at a higher rate for females between 2013 and 2017 (13.2% per year). This is a worrying trend. Moreover, Gayle (Reference Fortune and Hawton2019) reports an 11.8% increase in deaths by suicide among young people aged 10–24 in the UK. However, it can also occur in much younger children (<11 years old, i.e. prepubertal). It is estimated that in 2016 approximately 10 000 deaths by suicide worldwide were of children aged 10 or younger (World Health Organization 2016). The lower relative rate of suicide for prepubertal children means that there is less research available for this age group. Research for adolescents is less easily applied to younger children, owing to developmental differences between the two age groups.

Developmental differences among children and young people

In a systematic review aiming to inform suicide prevention strategies in primary schools, the Australian charity Headspace (2018) identified a number of risk factors in childhood and adolescence. This section includes some of their findings.

There are misconceptions that prepubertal children lack the cognitive maturity to engage in suicide (Kõlves Reference Kessler, Sonnega and Bromet2014). Most children understand death by the age of 8 and have an understanding of suicide by age 10 (Pfeffer Reference O'Connor and Nock1997). Data from the USA for 1999–2015 suggest a steep increase in prevalence of suicide between the ages of 8 and 9 for boys, with a less significant increase for girls at this age but still almost doubling (Hanna Reference Burnam, Stein and Golding2017).

A crucial element in child suicidal ideation is the intent to kill or harm oneself rather than their understanding of the finality or lethality of their attempt (Martinez 2013, cited in Headspace 2018). Children (depending on their age) may not understand the finality of death or the lethality of certain acts (Pfeffer Reference O'Connor and Nock1997). However, this does not prevent them from killing themselves. Their level of cognitive development will affect their problem-solving ability and capacity for emotion regulation. If a child does not have a supportive family, they may not have access to resources (from an adult) to help them overcome these problems that could crucially prevent suicide.

Suicide in children is thought to occur after short periods of distress (Oquendo & Mann 2008, cited in Headspace 2018). This has implications for early help for children following/during an acute period of distress. Risk factors for child suicide include the presence of a mental health problem (Grøholt Reference Gayle2003), disorganised or insecure attachment (Pfeffer Reference O'Connor and Nock1997), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Sheftall Reference Pfeffer2016), autism spectrum disorder (Mayes 2013, cited in Headspace 2018), child sexual abuse (Tyler Reference Sheftall, Asti and Horowitz2002), biological/hormonal changes particularly relating to the transition to puberty when suicide rates increase (Westefeld Reference Simms, Scowcroft and Isaksen2010), family conflict (Rajalin 2013), bullying/cyberbullying (van Geel Reference Silverman, Berman and Sanddal2014), problems at school, social isolation/lack of social support (Westefeld Reference Simms, Scowcroft and Isaksen2010), family history of mood disorder and/or suicide and stressful life events (Gould Reference Franklin, Ribeiro and Fox1996). On the contrary, Westefeld et al (Reference Simms, Scowcroft and Isaksen2010) suggest that protective factors for children include a warm, supportive family with either no abuse or abuse identified and responded to at an early stage; early identification and intervention for mental health difficulties; psychoeducation of those in contact with children regarding suicide; and intervention following suicide of another to prevent the child seeing this as a viable solution/contagion.

Differences in risk factors have been reported that suggest changes as a child moves into adolescence. Sheftall et al (Reference Pfeffer2016) report on age differences in a USA population of children (5–11 years of age) and early adolescents (12–14 years) who died by suicide between 2003 and 2012. Risk increased for females as they moved into adolescence. It also increased if the young person had depressed mood and/or depression. Risk was higher for children with a diagnosis of ADHD than for adolescents with the same diagnosis. This could be interpreted as being due to improved impulse control as a child ages. Ethnicity was significant, with more Black male children dying by suicide. In almost one-third of cases the children and young people told someone beforehand that they intended to kill themselves. Also of note is that interpersonal difficulties were precipitants across both age groups.

Adolescent suicidal behaviour

Suicide and self-harm increase during adolescence. Hanging is the most common method of suicide in the UK for both children and adolescents (Fortune 2007; Office for National Statistics 2019). Half of suicide attempts are first attempts and most are impulsive, with only 25% having evidence of planning (Berman Reference Berman, Jobes and Silverman2006). This impulsivity is perhaps linked to the sensation-seeking and increased risk-taking behaviour seen in adolescence (Blakemore Reference Blakemore2019). Adolescence is a time of significant neurological changes, alongside hormonal, social and physical change, all during a time when the young person's identity is developing and they are trying to make sense of themselves and where they fit in the world, with acceptance by others being crucial to them. This transition raises many challenges where they may not yet have the skills to identify alternative solutions and may feel isolated and perhaps less open with their families than in earlier life, owing to the drive to individuate. This perhaps provides some context for the risk factor of interpersonal difficulties as a precipitant. Further, the onset of puberty, along with the associated neurological changes, can increase vulnerability to developing mental health difficulties (Blakemore Reference Blakemore2019). Difficulties with affect control are thought to be linked to increased mental health difficulties in this group (Schweizer Reference Petrak, Doyle and Williams2020).

Risk factors for adolescent suicide include (in addition to those mentioned above for children) depression (Sheftall Reference Pfeffer2016), being a looked after child (Wadman Reference Silverman, Berman and Sanddal2017), struggles with sexuality or gender, aggression and impulsivity (Berman Reference Berman, Jobes and Silverman2006), difficulties in peer relationships, family difficulties and sleep difficulties (Buchman-Schmitt Reference Brooker and Durmaz2014). Furthermore, youth who cut themselves repeatedly have a significant risk of suicide (Cooper Reference Chan, Bhatti and Meader2005). Community studies have indicated rates of self-harm in adolescents to be 15.9–18% (e.g. Muehlenkamp Reference Klonsky and May2004). The period of adolescence has the highest lifetime prevalence of self-harm (Hawton Reference Grøholt and Ekeberg2008).

Vulnerability factors across the lifespan: adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

Other factors should be considered when determining contributing vulnerability factors for increased risk of self-harm and suicide in all age groups. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study began in the USA in 1995 and long-term follow-up has resulted in much published research (e.g. Felitti Reference Dazzi, Gribble and Wessely1998) identifying which ACEs lead to poor health and social outcomes and also mapping life-time risk consequent to these ACEs. ACEs were identified as child abuse/neglect, domestic violence, substance misuse, mental illness, criminality, parental separation and living in care. The research found that one or more ACEs lead to poor outcomes across a range of domains and can include reduced life expectancy. The risk of suicide increases significantly the more ACEs someone has experienced (Bellis Reference Bellis, Hughes and Leckenby2014). The World Health Organization (2013, cited in Allen Reference Allen and Donkin2015: p. 11) summarised the strength of evidence on health outcomes following childhood abuse. It reported a robust association between child sexual abuse and depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, suicide attempts and self-harm, substance misuse, eating disorders, personality disorders, and sexually transmitted infections and risky sexual behaviour.

Sexual violence and suicidal ideation

Adults

Experiencing sexual violence is one of the most significant risk factors for suicide. Suicidal ideation and self-harm are common in people who have been sexually assaulted, with studies dating back to 35 years ago stating that up to 44% report suicidal ideation and 19% reporting self-harm (e.g. Kilpatrick Reference Joiner1985). These figures are unlikely to have changed significantly in recent years. Furthermore, a study conducted by Petrak et al (Reference O'Connor, Gaynes, Burda, Williams and Whitlock1997) in a busy central London genito-urinary medicine clinic found that 16% of women referred to a psychology service after experiencing sexual assault had made a suicide attempt (all by overdose) post-assault and that 9% had taken the overdose within 24 h of the assault having occurred. In the same study, 41% of women had attempted suicide prior to the recent sexual assault. As regards London's SARC statistics, an audit carried out in 2008 (Heke Reference Hanson, Kilpatrick, Falsetti, Freedy and Hobfoll2009) on risk identification among adults attending the service found that 14% had attempted suicide and 14% had self-harmed. However, it is unclear whether the suicide attempts and the self-harm occurred before or after the sexual assault. We believe that this figure is likely to be consistent across other SARCs in the UK. Moreover, a report by NHS England (Reference Macdowall, Gibson and Tanton2013) states that there is an increased risk of suicide for abused children when they reach their mid-twenties and more recent figures from the Office for National Statistics (Reference O'Connor, O'Connnor, Platt and Gordon2018) suggest that nearly two-thirds of complainants of rape and sexual assault (63%) suffered mental or emotional problems as a result of the assault and one in ten attempted suicide.

Children and young people

Khadr et al (Reference Jacobs2018) conducted a prospective cohort study of a clinical population of adolescents (age 13–17) accessing the Havens (London's SARC). The study looked at characteristics of the adolescents in terms of demographics and mental health presentation. Shortly after reporting child sexual abuse, 90% of the participants were at risk (as measured by screening questionnaires) of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 88% were at risk of depression and 71% were at risk of anxiety disorder. This risk decreased over time for depression but less so for PTSD and anxiety disorders. At 4–5 months post-assault, 80% had at least one psychiatric disorder. Interestingly, these were linked to pre-existing vulnerability factors rather than characteristics of the offence, in contrast to the understanding of mental health outcomes following sexual offences (e.g. Chen Reference Callaghan, Waldock, Callaghan and Waldock2010) that cites the offence as the precipitant of mental health difficulties. In the 12 months before the reported incident, 41% of the sample self-harmed. Of course, the child sexual abuse might have been ongoing before the reported incident and so the self-harm may be in this context. Additionally, 72% were the most socially deprived, as classified by the index of multiple deprivation for England (cited in Khadr Reference Khadr, Clarke and Wellings2018). The least deprived in the sample were at higher risk for developing PTSD and anxiety disorders, and 8% of females became victims of a further sexual assault (Khadr Reference Jacobs2018), for reasons thought to relate to their vulnerability. When previous mental health support was controlled for, previous Social Services involvement was significant in terms of later mental health outcomes, whereas previous self-harm and previous child sexual abuse were not.

A study by Tomasula et al (2012) on the link between child sexual abuse and suicide in adolescents in the USA found that males who had experienced child sexual abuse were 10 times more likely to attempt suicide than males who had not. In turn, female victims of child sexual abuse were five times more likely to attempt suicide than non-victims. Victims of child sexual abuse were also more likely to carry out medically serious self-harm and more medically serious suicide attempts than non-victims. This was more apparent for males than females. Although the authors acknowledge that the method of data collection may have led to underestimating the scale of the problem, the results are alarming in terms of the consequences for SARCs of keeping young people safe from suicide and self-harm. Given the evidence on the link between sexual assault/child sexual abuse and the increased risk of self-harm and suicide, it is crucial that SARCs and other services consider how to assess, understand and manage risk.

Identifying and assessing risk and protective factors

The pathways to suicide are complex and although knowledge of risk factors for suicide has grown considerably in recent decades (O'Connor 2014), this has not translated into an improvement in practitioners’ ability to predict suicide (Hawton Reference Hanna2012; Turecki Reference Schweizer, Parker and Leung2016; Franklin Reference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg2017) or to successfully and consistently reduce risk of self-harm and suicide (Bloomer Reference Bloomer2018). Nonetheless, the causes of suicide are many and understanding the psychological processes behind suicidal ideation and the factors that lead individuals to act on their thoughts is crucial to the development and implementation of a risk management plan.

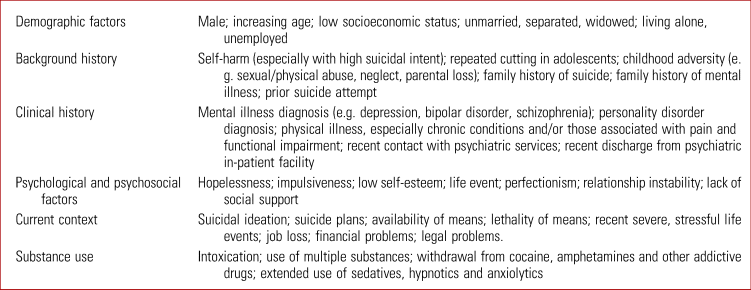

The concept of risk must be associated with a holistic approach to working with people's needs, vulnerabilities and risk to self (British Psychological Society Reference Silverman, Berman and Sanddal2006). Suicidality revolves around a complex interplay between risk factors. It is therefore important to consider the contribution of biological, psychological and social factors (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Risk factors for suicide

Sources: Bryan & Rudd (2006); Department of Health & National Risk Management Programme (Reference Cooper, Kapur and Webb2007); Jacobs (Reference Hawton and Harriss2007).

When to assess risk in a SARC and what to ask

Risk is dynamic, changing over time, and should be assessed at every contact (Box 2). When assessing risk, it is important to balance the seriousness of the possible outcomes with the probability that they will occur, based on specific risk factors. This means that, however confident and competent a practitioner might be in the assessment of risk, there can never be an absolute guarantee. When assessing suicidal ideation, questions should be directed towards determining the presence or absence of: suicidal ideation, the persistence of the ideation, the likelihood of it being acted on and risk to others. Furthermore, it is important to assess level of hopelessness; whether the patient has thoughts about a specific, available method of suicide; whether they have ever acted on such thoughts in the past; whether they are able to dismiss the thoughts; ability to reassure you of their safety, for example until the next appointment; circumstances likely to make things worse; willingness to ask for help if crisis occurs. It is important also to be mindful that some patients who are experiencing suicidal ideation deliberately deny having such thoughts. Other factors to be aware of include the use of drugs and/or alcohol and a marked change in psychiatric symptomatology, such as psychomotor retardation. In individuals presenting with psychomotor retardation, the risk of suicide may increase as their condition improves because of the reduction in inhibition. It is also important to consider the developmental stage of the patient and any risk factors specific or relevant to that age group.

BOX 2 When to assess risk in a sexual assault referral centre (SARC)?

• At initial assessment – this can be the initial telephone screening

• On first attendance at the SARC

• At every subsequent appointment following initial attendance

Risk is dynamic and therefore can change over time, hence the need to assess the patient's risk to self at every contact

Contrary to some myths around suicide, there is no evidence to suggest that enquiring about suicidal thoughts and/or suicidal plans increases risk of suicidal ideation or self-harm. In fact, there is some evidence that it is beneficial for those at higher risk (Dazzi Reference Chen, Murad and Paras2014).

Box 3 lists questions to be considered when conducting a risk assessment with a patient.

BOX 3 Questions to consider when conducting a risk assessment

• Have you ever attempted to take your own life or harm yourself in the past? [Assess recency, severity, frequency]

• Do you use alcohol and/or other illicit substances? [Assess details of the substance, quantity and frequency]

• Do you have any current mental health-related difficulties?

• Do you have any current physical health conditions?

• Have you ever known anyone who has taken their own life or self-harmed?

• Do you ever feel hopeless and have thoughts of being better off dead? [Assess the frequency and persistence of thoughts, and the ways the patient manages them]

• Do you have any specific plans to harm yourself? Do you have images about completing this? [Gain details of these plans, including the means, date and location]

• How likely are you to act on these thoughts at the moment? [Rate intent on a scale of 0–10]

• What has stopped you from acting on these thoughts in the past?

• Children/adolescents: as well as asking the above questions, it is important to clarify who else knows about the risk (i.e. peers or a trusted adult) and, depending on the answer, discuss limits to confidentiality and devise a safety plan that involves making a trusted adult aware – this depends also on the nature of the risk and individual circumstances. It would also be important to clarify the patient's understanding of the consequences of certain acts, e.g. whether they understand that it could lead to death.

Should risk assessment tools be used?

Although the risk assessment guidance provided in this article may seem familiar to many practitioners, it is nonetheless important to include it. Despite the existence of a number of risk assessment scales for suicide, none to date provides enough robust evidence to justify their routine use in clinical settings (Bolton Reference Bolton, Gunnell and Turecki2015; Chan Reference Burnam, Stein and Golding2016; Quinlivan Reference O'Connor and Kirtley2017). It is therefore not surprising that NICE stresses the importance of conducting a risk assessment but does not support the use of specific risk assessment tools (NICE Reference Kõlves and De Leo2011).

A psychosocial assessment that is carried out in a compassionate manner is key to establishing a positive rapport between a clinician and a patient in distress. It is also important to ask about suicide in a direct but sensitive manner.

When carrying out a risk assessment, it is important to identify protective factors that might reduce the risk of suicide. Some patients who present with protective factors still attempt and carry out suicide, but protective factors often contribute to increased resilience when faced with stress and/or adversity.

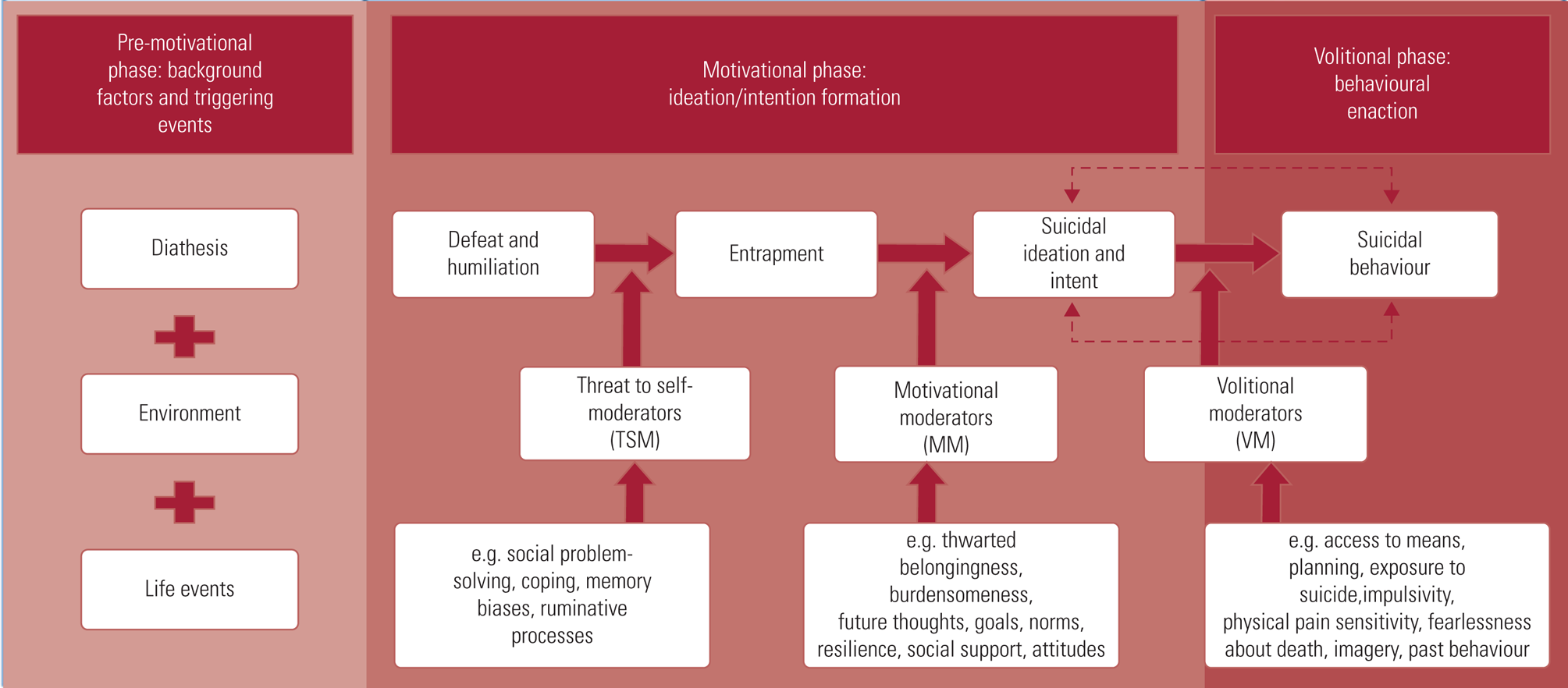

Understanding the pathway – a model

There are several theoretical models that attempt to describe the pathways to suicide (e.g. Joiner Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2005; O'Connor 2011; Klonsky Reference Jonas, Bebbington and McManus2014). We chose to focus on the integrated motivational–volitional model (IMV) of suicidal behaviour by O'Connor (2011), which centres on factors that mediate ideation to action. The IMV model (Fig. 2) suggests that factors leading to suicidal thinking are different from those that govern the transition from thinking about suicide to attempting suicide (O'Connor 2014). This model suggests that suicidal ideation emerges from feelings of defeat or humiliation from which there is no escape (O'Connor 2011, 2013). The IMV model postulates that acting on thoughts of suicide is governed by volitional moderators (e.g. impulsivity, exposure to suicide, fearlessness about death), which increase the probability of suicide attempts/death by suicide.

FIG 2 The integrated motivational–volitional (IMV) model (O'Connor & Kirtley 2018, reproduced with the authors’ permission).

The IMV model is relevant to the SARC population in that sexual violence can often be characterised by a feeling of defeat or humiliation from which there is no escape. These factors could form an important part of a risk assessment.

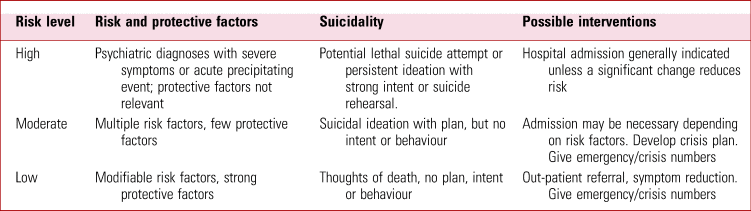

Good practice: risk assessment and management

Assessment of the level of risk is based on clinical judgement, as well as consideration of the risk and protective factors present, and on a detailed suicide risk assessment. This should ideally be discussed within the multidisciplinary team, so that risk is considered and held by teams rather than by individuals. Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage (SAFE-T) (Suicide Prevention Resource Center Reference Rajalin, Hirvikoski and Jokinen2009) is a comprehensive and easy to understand assessment model that can be readily applied to most clinical contexts (Box 4).

BOX 4 Key steps of Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage (SAFE-T)

1 Identify risk factors

2 Identify protective factors

3 Carry out a suicide assessment, e.g. ideation, plans, behaviours, intent

4 Determine the risk level and intervention required

5 Document

(Adapted from Suicide Prevention Resource Center Reference Rajalin, Hirvikoski and Jokinen2009)

Risk management involves devising a care plan to minimise harmful behaviour and maximise beneficial behaviour (Callaghan Reference Buchman-Schmitt, Chiurliza and Chu2006):

• In case of immediate threat, the practitioner should take action to get the patient into an appropriate setting. This is likely to be the local accident and emergency (A&E) department. The should contact the patient's general practitioner at the earliest opportunity.

• If risk is present but not immediate, the practitioner should develop a treatment plan for managing risk, which should be shared with the patient. This plan could include short-term strategies for ensuring safety, crisis planning for high-risk situations, involving significant others and referral for psychological therapy. It should also include moderating any risk factors where possible.

Documentation is a standard practice in healthcare settings and clear and complete documentation of the suicide risk assessment and plan is crucial. The level of risk and rationale should be documented as well as the plan to safeguard the patient, such as referral to A&E psychiatry liaison or referral to a community mental health team or child and adolescent mental health team. Practitioners must also follow up on any referrals made to ensure that the patient is receiving the appropriate care.

Key points in risk assessment and management are outlined in Table 2 and Box 5.

TABLE 2 Risk assessment and management

Source: Suicide Prevention Resource Center (Reference Rajalin, Hirvikoski and Jokinen2009).

BOX 5 Key points in risk management

• Develop a care plan and a safety plan to give to the patient – include triggers to thoughts of self-harm and appropriate responses to those triggers, starting with the least intrusive (i.e. use coping skills) to most intrusive (call 999/go to an accident and emergency department) (Berk Reference Berk, Henriques and Warman2004)

• Information-sharing with others after discussing limits to confidentiality (parents, Social Services, service multidisciplinary team, Trust safeguarding leads, general practitioner, other agencies involved)

• Providing patients written or recorded copies of plans, including crisis contact numbers

• Accurate record-keeping

• Timely follow-ups

• Continued monitoring: risk is dynamic, not static – continued risk assessment is needed

• Consultation with the multidisciplinary team is always recommended

Conclusions

All practitioners in contact with patients must receive adequate training on the assessment and management of risk to self to ensure they feel equipped to support a suicidal patient and be able to implement the most appropriate plan to safeguard them. Risk assessment and management is a continuous and dynamic decision-making process. Practitioners should be aware of the strong association between sexual assault and suicide and self-harm and familiarise themselves with the literature on risk factors and protective factors for suicide, to increase confidence in carrying out risk assessments.

Suicidal ideation and behaviours warrant a thorough assessment. Asking about recent stressors, thoughts about suicide, family history and other factors associated with increased risk will help the practitioner to assess suicide risk. Interventions to reduce risk might focus on modifiable risk factors, such as treating psychiatric disorders and symptoms, addressing psychological stressors and strengthening social support networks.

Collecting and communicating information is an important aspect of any risk assessment and management strategy. Partnership working is therefore essential when it comes to effective risk management. No individual professional or agency can operate in isolation when working with risk.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the writing of this article.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2020.48.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 Risk factors for suicide in the adult population include:

a living alone

b substance use

c mental illness diagnosis

d hopelessness

e all of the above.

2 Assessment of the level of risk is based on:

a clinical judgement, risk and protective factors and a suicide risk assessment

b risk assessment scale only

c number of risk factors present

d number of previous suicide attempts and/or history of self-harm

e feedback from significant others.

3 Khadr et al's 2018 study of adolescents who experienced child sexual abuse found:

a that the risk increased over time for depression

b no link between mental health difficulties and pre-existing vulnerability factors

c that 15% of females were re-victimised

d that at 4–5 months post-assault, 80% of adolescents had at least one psychiatric disorder

e none of the above.

4 Different risk levels and presence of protective and risk factors may lead to different risk management pathways. Which of the following is correct?

a if risk is moderate, a practitioner should always offer voluntary admission

b if risk is low, it will remain low for the following weeks

c if risk is deemed high, admission is generally indicated unless a significant change reduces risk

d if risk is low, follow-up is optional

e all of the above.

5 What does effective care within the context of a SARC involve?

a only addressing physical health needs

b only addressing mental health needs, as approximately 40% of individuals accessing SARCs have pre-existing mental health problems

c addressing both the mental health and the physical health needs of victims of sexual assault

d only addressing a need that an individuals has explicitly asked for help with

e none of the above.

MCQ answers

1 e 2 a 3 d 4 c 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.