The number of elderly people is progressively increasing. Besides medical progress, the life expectancy increase could also be linked to environmental and behavioural factors, some of which can be modified to achieve beneficial effects for health, particularly dietary habits( Reference King, Mainous and Geesey 1 ). The importance of diet has led public health policymakers to develop specific prevention programmes. Moreover, large observational studies have examined the relationship between diet and all-cause mortality in elderly subjects using various food habit classifications that focus, for example, on specific foods or food consumption groups or on dietary patterns that combine multiple features. The results show that some dietary patterns (eating habits, including several food groups), such as the Mediterranean diet( Reference Trichopoulou, Kouris-Blazos and Wahlqvist 2 – Reference Chrysohoou and Stefanadis 13 ) or ‘healthy’ dietary groups defined by high consumption of fruits, vegetables and fish( Reference Kumagai, Shibata and Watanabe 14 – Reference Iimuro, Yoshimura and Umegaki 17 ) or greater consumption of olive oil with raw vegetables( Reference Masala, Ceroti and Pala 18 ), have a protective effect. Similarly, some studies on consumption frequency found that high intakes of fruits and/or vegetables( Reference Strandhagen, Hansson and Bosaeus 19 – Reference Sahyoun, Jacques and Russell 21 ), fish( Reference Darmadi-Blackberry, Wahlqvist and Kouris-Blazos 20 , Reference Gillum, Mussolino and Madans 22 ) or coffee( Reference Fortes, Forastiere and Farchi 23 – Reference Freedman, Park and Abnet 25 ) have a beneficial effect on survival. However, a few of these studies have considered the most relevant adjustment factors. Indeed, dietary habits and mortality are both influenced by many factors not only at the individual level (age, sex, health status, socio-economic, cultural and genetic factors) but also at the population level (for instance, food availability and accessibility in terms of cost).

Another way to assess the effect of diet on health is to consider the concept of food diversity. The advantage of studying the diversity of diets and of used fats compared with monotonous diets is that it allows evaluating the consumption of the most essential micronutrients and of different types of fatty acids (FA). This concept is a part of the French National Health and Nutrition Programme ( 26 ). Indeed, a varied diet, defined by the daily consumption of at least 1 unit of each essential food group, has been associated with a lower mortality risk( Reference Kant, Schatzkin and Harris 27 , Reference Lee, Huang and Su 28 ). However, a few studies have focused on this approach.

Therefore, our main objective was to examine the associations between dietary habits and mortality in an elderly population. The data collected by the 10-year follow-up study of the large French population-based Three-City (3C) cohort allowed investigating whether some dietary habits (consumption of fruits, vegetables, olive oil, fish and caffeine, diet diversity and diversity of used fats) are associated with reduced all-cause mortality in people aged >65 years, independently of previously identified major confounders.

Methods

Data were extracted from the database of the 3C study, a prospective cohort study of vascular risk factors of dementia( 29 ). The present study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. The 3C study protocol was approved by the Consultative Committee for the Protection of Persons participating in Biomedical Research of the Kremlin-Bicêtre University Hospital (Paris, France). All participants signed a written informed consent.

Participants

A sample of community dwellers aged 65 years and older was selected in 1999/2000 from the electoral rolls of Bordeaux (South-West of France), Montpellier (South-East of France) and Dijon (North-East of France). To be eligible for recruitment into the study( 29 ), persons had to be (1) living in these cities or their suburbs and registered on the electoral rolls, (2) aged 65 years and older and (3) not institutionalised. The cohort size by centre was set at 2500 in Bordeaux, 5000 in Dijon and 2500 in Montpellier. A personal letter was sent to each potential subject inviting them to participate, including a brief description of the study protocol and an acceptance/refusal form. The spouse/partner was also invited to participate in the study if he/she met eligibility criteria. As electoral rolls are occasionally inaccurate (persons who have moved may still be registered at their previous address), no further correspondence was sent to persons who did not respond to the first letter, but an attempt was made to contact them by telephone. In total, 24 % of the eligible persons selected from the electoral rolls (n 34 922) could not be reached; among those contacted, the acceptance rate was 37 %. A total of 9693 persons were included; seven persons aged <65 years were subsequently excluded. Participants who had subsequently refused to participate in the baseline medical interview (n 392) were excluded from all analyses leading to an original sample of 9294 community dwellers.

The participants were administered standardised questionnaires and underwent clinical examinations at baseline and after 2, 4, 8 and 10 years. Baseline data were collected by standardised face-to-face interviews. They included information on socio-demographic features, lifestyle (including a brief FFQ), current symptoms and complaints, medical history, blood pressure, past and present consumption of tobacco, alcohol and drug use, anthropometric data, neuropsychological testing and blood sampling.

For the present study, the following participants were excluded: 132 (1·4 %) subjects with missing data for at least one dietary variable, 214 (2·3 %) people with a diagnosis of dementia at baseline and eleven (0·12 %) individuals with no available vital statistics data. The analysis was thus carried out using a sample of 8937 participants with a mean follow-up of 8·85 years.

Baseline dietary assessment

The brief FFQ was administered at baseline to assess the participants’ dietary habits concerning nine broad food categories: (1) meat and poultry, (2) fish (including seafood), (3) eggs, (4) milk and dairy products, (5) cereals (including bread and starches), (6) raw fruits, (7) raw vegetables, (8) cooked fruits or vegetables and (9) pulses. Consumption frequency was classified as follows: never, <1 time/week, 1 time/week, 2–3 times/week, 4–6 times/week and daily. The dietary habits of the whole sample have been described previously( Reference Larrieu, Letenneur and Berr 30 ). Participants were also invited to indicate the dietary fats used at least 1 time/week for dressing, cooking or spreading among those included in the following list: butter, margarine, maize oil, peanut oil, sunflower or grapeseed oil, olive oil, blended oil, duck or goose fat, lard, ‘Vegetaline©’ (mainly SFA), colza oil, walnut oil and soyabean oil. Caffeine consumption was calculated by multiplying the number of cups of tea and/or coffee consumed per day by their estimated caffeine content (about 50 mg/cup for tea and 100 mg/cup for coffee)( Reference Ritchie, Carriere and de Mendonca 31 ).

Fruits/vegetables, fish, meat and olive oil were the four main food consumption groups of interest that were studied as categorical variables. Their consumption thresholds were based on the French National Nutrition and Health Programme guidelines, when applicable to the available data( 26 ). Cooked fruits and vegetables, olive oil and caffeine consumptions were investigated using previously defined categories( Reference Ritchie, Carriere and de Mendonca 31 – Reference Ritchie, Artero and Portet 33 ). Dietary habits included the intake of fish/seafood (<2 times/week v. >2 times/week), fruits and vegetables (<1 fruit and 1 vegetable, cooked or raw/d v. at least 1 fruit and 1 vegetable, cooked or raw/d, and <4–6 servings of cooked fruits or vegetables/week v. >4–6 servings of cooked fruits or vegetables/week), meat (<1 time/d v. >1 time/d), caffeine (<250, 250–375, >375 mg/d). Further, three categories of olive oil consumption were defined: ‘no use’, ‘moderate use’ (for cooking or dressing alone) or ‘intensive use’ (for cooking and for dressing)( Reference Berr, Portet and Carriere 32 , Reference Samieri, Feart and Proust-Lima 34 ). To calculate the diet diversity score (DDS) (from 0 to 5), one point was assigned for each of the following food categories consumed at least once per day: dairy products, meat, cereals, fruits and vegetables. Low diversity was defined by a DDS<3 and high diversity by a DDS≥4( Reference Kant, Schatzkin and Ziegler 35 ). Fat diversity was evaluated as ≤3 different fats v. >3 fats. The threshold of the three different fats corresponds to the median value of various fats used by the population included in the 3C cohort.

Baseline covariates

Socio-demographic information recorded at baseline included age, sex, centre, educational level (no or primary/middle/high school/university), occupation (white collar, employee, blue collar, housewife) and monthly income level (<1500, >1500 euros). Health behaviours were assessed on the basis of smoking status (no, 0–10, 10–30 or >30 packets/year) and intake of alcoholic beverages (0–24, >24 g/d for women; 0–36, >36 g/d for men).

Blood pressure and anthropometric data were measured in standardised conditions. Health-related variables included BMI (<27 and ≥27 kg/m2)( Reference Heiat, Vaccarino and Krumholz 36 ), hypertension (defined as a systolic blood pressure>140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure>90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive drugs)( Reference Brindel, Hanon and Dartigues 37 ), diabetes (fasting blood glucose≥7·0 mmol/l or use of anti-diabetic drugs), hypercholesterolaemia (yes/no, self-reported) and the number of drugs used (0, 1–4, ≥5). History of CVD (yes/no) and other chronic diseases (chronic respiratory disease, cancer, Parkinson’s disease or hypothyroidism) was reported. Disability was estimated using the instrumental activities of daily living scale (yes (score>0)/no). Depressive mood was assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale and was defined by a score <17 for men and <23 for women. Self-rated health was grouped into three categories (poor, average, fair) and self-assessment of correct diet into two classes (no/yes).

Physical activity was assessed differently in the three centres (self-reported or not and with different accuracy levels). Therefore, a common binary variable was considered for the three centres (none, low or regular). Regular physical activity was defined as taking part in some sport regularly or having at least 1 h of leisure or household activity/d( Reference Feart, Lorrain and Ginder Coupez 38 ). Given the important amount of missing data for this variable (1115 missing data for the Bordeaux centre, 11 % of the whole sample), it was used only in sensitivity analyses.

Vital status

Mortality was ascertained from the civil registry by systematic request for all subjects not included in follow-up visits. The date of death was defined as the date of the event, and the date of the last follow-up or phone contact for the 10-year follow-up was considered as the date of censoring. Follow-up included the precise assessment of all causes of death that were coded according to the tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)( Reference Alperovitch, Bertrand and Jougla 39 ). Mortality from CVD (ICD-10: I) and cancer (ICD-10: C), the two leading causes of death in aged populations, were considered for the analyses( Reference Alperovitch, Bertrand and Jougla 39 ).

Statistical analyses

Survival analysis was carried out using the Kaplan–Meier method. Comparisons of baseline characteristics and dietary habits were performed using the log-rank test.

The associations between dietary habits, diet diversity and mortality risk were determined using Cox proportional hazards regression with delayed entry, with age (in years) used as the time axis and left truncation at the age of study entry. The results of the survival analysis are expressed as hazard ratios (HR) with 95 % CI.

In these analyses, the adjustments for covariates were performed in three steps. Univariate analysis was the basic model to test associations between dietary features and mortality (crude model). The second model (model 1) was adjusted for sex, study centre, educational level, occupation and income. Health behaviours and health factors, chosen on the basis of literature data, were then added to the third model (model 2). Interactions between the different dietary habits and covariates included in model 2 were tested and stratified analyses were carried out accordingly.

For missing data, multiple imputations were used by generating five copies of the original data set in which the missing values for the covariates considered in the analysis were replaced by values generated according to the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method and using the PROC MI procedure. Each imputed data set was analysed as if it were complete to calculate the mean HR and CI with the PROC MIANALYZE procedure( Reference Yuan 40 ). Imputations were performed for covariates included in the analyses: education (missing data 0·17 %), income (6·13 %), occupation (0·29 %), smoking (1·63 %), alcohol intake (1·51 %), history of CVD (0·08 %), depression (1·28 %), diabetes (5·65 %), hypertension (0·06 %), hypercholesterolaemia (1·1 %), dependence (0·69 %), self-rated health (0·57 %), number of chronic diseases (0·09 %) and self-rated diet quality (2·38 %).

Analyses were carried out using SAS software (version 9.2).

Results

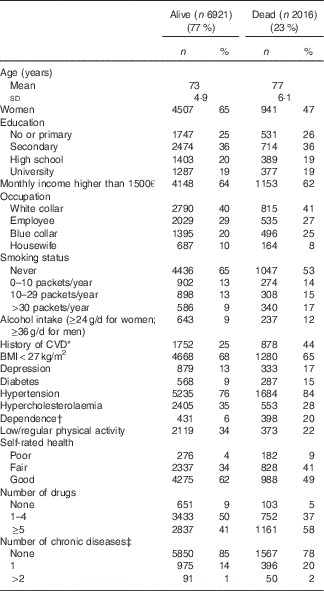

The baseline characteristics and dietary habits of the participants (n 8937) according to their vital status (dead/alive) at the end of the 10-year follow-up are reported in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Participants who died (n 2016) were significantly older at baseline than those still alive (mean age: 77 v. 73 years, respectively) and more often men, heavy smokers or alcohol consumers. They also had more often a history of CVD or chronic diseases, more vascular risk factors and poor self-rated health. In these crude comparisons, mortality risk was higher among individuals with low income and blue-collar workers. Conversely, survival was not influenced by the educational level in this highly educated population. Daily consumption of fruits and vegetables, regular consumption of cooked vegetables/fruits, intensive olive oil use, wide fat diversity and bi-weekly fish consumption were more frequently reported by subjects still alive at the end of the 10-year follow-up. Caffeine consumption and DDS were not associated with survival.

Table 1 Baseline socio-demographic and medical characteristics of the Three-City cohort (n 8937) subdivided according to their vital status (dead or alive) at the end of the 10-year follow-up (Numbers and percentages; mean value and standard deviation)

* CHD was reported in 671 (9·7 %) subjects who were alive and 398 (20 %) subjects who were dead at the end of the follow-up.

† Assessed using the instrumental activities of daily living scale (at least 1 impairment).

‡ Chronic diseases included mainly respiratory diseases and dyspnoea (n 477, 5·8 % of people still alive; n 285, 14·1 % of subjects dead at the end of the follow-up), Parkinson’s disease (n 46, 0·66 % of alive; n 59, 2·9 % of dead subjects) and hyperthyroidism (n 6, 18 9 % of alive; n 143, 7·1 % of dead subjects).

Table 2 Baseline food habits of the Three-City cohort (n 8937) subdivided according to their vital status (alive or dead) at the end of the 10-year follow-up (Numbers and percentages)

Next, the associations between the 10-year mortality risk and dietary habits or diet diversity (at baseline) were assessed after multiple imputations for missing data (Tables 3 and 4, respectively). In crude analyses, various well-known healthy food habits were significantly associated with better survival: eating at least 1 fruit and 1 vegetable (raw or cooked)/d, consumption of at least 4 cooked fruit/vegetable servings/week, consumption of at least 2 servings/week of fish, meat <1 serving/d, greater diet diversity and diversity in fat use.

Table 3 Association between 10-year overall mortality and dietary habits in the Three-City elderly cohort (n 8937) (Crude and adjusted hazard ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

*P<0·05, **P<0·01, ***P<0·001.

† Cox proportional model adjusted for sex, centre, education (no or primary/secondary/high school/university), income (<1500 or >1500 euros/month), occupation (white collar/employee/blue collar/housewife).

‡ Cox proportional model adjusted for sex, centre, education, income and occupation and also for smoking status, alcohol consumption, history of CVD, BMI, depression, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, dependence (instrumental activities of daily living scale), self-rated health, self-rated diet quality, number of drugs and number of chronic diseases.

Table 4 Association between 10-year overall mortality and diet diversity in the Three-City elderly cohort (n 8937) (Crude and adjusted hazard ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

*P<0·05, **P<0·01.

† Cox proportional model adjusted for sex, centre, education (no or primary/secondary/high school/university), income (<1500 or >1500 euros/month), occupation (white collar/employee/blue collar/housewife).

‡ Cox proportional model adjusted for sex, centre, education, income and occupation and also for smoking status, alcohol consumption, history of CVD, BMI, depression, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, dependence (instrumental activities of daily living scale), self-rated health, self-rated diet quality, number of drugs and number of chronic diseases.

In the partly (only socio-demographic covariates) and fully (socio-demographic and health-related covariates) adjusted models, consuming at least 1 fruit and vegetable/d and consuming >4 cooked fruit/vegetable servings/week remained significantly associated with a better survival compared with lower levels of consumption (HR 0·90; 95 % CI 0·82, 0·99, P=0·03 and HR 0·80; 95 % CI 0·70, 0·90, P=0·0005, respectively, in the fully adjusted models). Fish intake of at least 2 servings/week was also significantly associated with better survival (HR 0·89; 95 % CI 0·81, 0·97, P=0·01), whereas consuming meat >1/d had a deleterious effect on survival in the fully adjusted models (HR 1·12; 95 % CI 1·01, 1·24, P=0·03) (Table 3).

For the two indicators of diet diversity (DDS and diversity in fats used), the significant associations observed in crude and partly adjusted analyses were no longer significant after adjustment for health-related variables as well (Table 4).

As the interaction between sex and consumption of olive oil was significant, analyses were stratified by sex (online Supplementary Table S1). The use of olive oil was inversely correlated with mortality risk after adjustment for all covariates, but only in women (moderate olive oil use: HR 0·80; 95 % CI 0·68, 0·94, P=0·007; intensive use: HR 0·72; 95 % CI 0·60, 0·85, P=0·0002).

Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were performed on 5322 individuals with available data on physical activity. In this sub-sample, the consumption of at least 4–6 servings of cooked fruits or vegetables/week was again associated with a lower mortality risk at the end of the 10-year follow-up, independently of physical activity (HR 0·75; 95 % CI 0·62, 0·90, P=0·002). No association was observed between mortality risk and meat, fish or olive oil consumption (online Supplementary Table S2) or diet diversity (online Supplementary Table S3).

Finally, there was no significant association between dietary habits/diversity and the main causes of death (389 due to CVD and 542 due to cancer) after controlling for sex, centre, educational level, income and occupation (data not shown).

Discussion

The present study based on the 10-year follow-up of a French cohort of people aged 65 years or older suggests that healthy dietary habits such as daily consumption of fruits and vegetables, eating 2 servings/week of fish and regular use of olive oil (only in women) are significantly linked to better survival, independently of socio-demographic, health-related and lifestyle variables. Overall, higher diet diversity is associated with lower mortality risk.

A major difficulty when assessing food habits concerns the heterogeneity of the collected data. Indeed, each country has its consumption standards, tailored to cultural habits and the local availability of food resources. Moreover, the methods used to collect such data are also not homogeneous, and consequently results are difficult to compare and generalise from one country to another. Nevertheless, the various eating habits can be standardised in dietary patterns (such as composite scores or consumption patterns of some preferred foods) or by quantitative measurements of food types. Studies on diet quality or adherence to a particular diet are used to determine the most beneficial approach; however, in the case of composite scores, the proper role of each score component cannot be identified. In the present study, where food habits were evaluated with a short FFQ, we examined food groups that have been found to be associated with longer lifespan in previous studies using these different approaches. Our results are in agreement with the French National Nutrition and Health Programme guidelines that include the promotion of daily consumption of fruits and vegetables( 26 ).

We observed a significant association between high consumption of fruits and vegetables and survival after adjusting for major confounders. This result is consistent with earlier studies( Reference Strandhagen, Hansson and Bosaeus 19 – Reference Sahyoun, Jacques and Russell 21 ). In the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study, a better adherence to a plant-based diet was associated with a reduced mortality risk in Southern Europe, but not in the UK or in Germany, after controlling for all known risk factors( Reference Bamia, Trichopoulos and Ferrari 15 ). Similarly, the ‘Olive oil and salad’ pattern was associated with longevity in an Italian elderly cohort( Reference Masala, Ceroti and Pala 18 ).

Fruits and vegetables, which were not separate entities in our FFQ, are the main source of antioxidants that are the basis of the free-radical theory of ageing( Reference Harman 41 ). According to this theory, a balance between free radicals and antioxidants increases life expectancy. Some authors hypothesise that plant foods promote the activation of immune functions or have protective properties( Reference Anderson, Harris and Tylavsky 16 , Reference Iimuro, Yoshimura and Umegaki 17 ). A recent literature review highlighted the effect of high concentrations of polyphenols, carotenoids, folic acid and vitamin C on mortality( Reference Chrysohoou and Stefanadis 13 ). High consumption of flavonoids, found mainly in fruits, could be associated with reduced mortality risk( Reference Ivey, Hodgson and Croft 42 ). The beneficial effects of fruits and vegetables could also be explained by their fibre content that modulates LDL-cholesterol level, insulin sensitivity and blood pressure( Reference Streppel, Ocke and Boshuizen 43 ), all conditions associated with increased mortality risk. This hypothesis is supported by the PREDIMED (Prevention con dieta Meditteranea) study that demonstrated a significant association between lower risk of death and baseline higher fibre intake and fruit consumption( Reference Buil-Cosiales, Zazpe and Toledo 44 ).

Our results are in agreement with the few studies that have investigated fish consumption and risk of death( Reference Darmadi-Blackberry, Wahlqvist and Kouris-Blazos 20 , Reference Gillum, Mussolino and Madans 22 ). A Japanese study found that high consumption of vegetables and fish in subjects older than 75 years is associated with better survival( Reference Iimuro, Yoshimura and Umegaki 17 ). Most of the published studies on the positive association between fish and lower mortality have been carried out in countries with traditional high fish consumption (Japan and Scandinavia). Other studies included fish consumption in the diet scores (e.g., the Mediterranean Diet Score) or in ‘healthy’ diet patterns( Reference Kumagai, Shibata and Watanabe 14 , Reference Anderson, Harris and Tylavsky 16 , Reference Hoffmann, Boeing and Boffetta 45 ) with contrasting results. Hoffman et al.( Reference Hoffmann, Boeing and Boffetta 45 ) did not find any significant association between these dietary patterns and mortality. Conversely, Anderson et al.( Reference Anderson, Harris and Tylavsky 16 ) observed a positive link between survival and a healthy dietary pattern (consumption of low-fat dairy products, fruits, wholegrains, poultry, fish and vegetables). The protective effect of fish consumption on health has been linked to the anti-inflammatory effects of the essential n-3 fatty acids( Reference Chrysohoou and Stefanadis 13 , Reference Gillum, Mussolino and Madans 22 ).

Olive oil is the main source of fat in the traditional Mediterranean diet. Our study reported a beneficial effect only among women. This finding is in agreement with the findings in an elderly British cohort( Reference Hamer, McNaughton and Bates 7 ), where the Mediterranean style dietary pattern was associated with reduced mortality only in women. This sex-specific effect could be explained by women’s longer life expectancy. Many studies support the beneficial effect of the Mediterranean diet on mortality( Reference Trichopoulou, Kouris-Blazos and Wahlqvist 2 – Reference McNaughton, Bates and Mishra 8 , Reference Trichopoulou, Orfanos and Norat 12 , Reference Knoops, Groot de and Fidanza 46 ). Masala et al.( Reference Masala, Ceroti and Pala 18 ) observed that the ‘olive oil and salad’ dietary pattern (high consumption of olive oil) is inversely associated with all-cause mortality in the elderly. The PREDIMED study found that higher consumption of olive oil was associated with a specific reduction in the cardiovascular mortality risk in an elderly Mediterranean population( Reference Guasch-Ferre, Hu and Martinez-Gonzalez 47 ). The beneficial effect of olive oil could be explained by its high concentrations of MUFA and phenolic compounds that improve endothelium function and reduce oxidative stress, thereby promoting healthy ageing and longevity( Reference Chrysohoou and Stefanadis 13 ).

On the other hand, we found that daily consumption of meat, as a broad category, had a negative effect on survival. Most previous studies showing a deleterious effect of meat consumption on lifespan( Reference Iimuro, Yoshimura and Umegaki 17 , Reference Hoffmann, Boeing and Boffetta 45 ) also found that high meat consumption patterns were often associated with unhealthy dietary habits such as high levels of fat consumption. However, in other studies, red meat consumption was not associated with increased mortality risk after correction for confounding factors( Reference Anderson, Harris and Tylavsky 16 ). Comparisons with previous findings are limited by the different definitions of meat consumption groups. In some studies red meat with high content of FA was considered on its own, whereas poultry or lean meat was not included in the analysis. Anderson et al.( Reference Anderson, Harris and Tylavsky 16 ) suggested that high consumption of animal foods could increase the mortality risk, only if meat replaces protective plant foods in the diet. The link between red meat and dietary fat could affect the lipid and lipoprotein profile, and thus CVD risk( Reference Hoffmann, Boeing and Boffetta 45 ).

The association between diet diversity and mortality did not remain significant after adjustment for confounders unlike in other studies( Reference Kant, Schatzkin and Harris 27 , Reference Lee, Huang and Su 28 ). However, comparisons are difficult because these studies used different methods of food collection and different food groups.

The data from our study should be interpreted in the light of the following limitations. First, the 3C sample is not representative of the French population. Indeed, compared with the whole French population, this cohort included more urban dwellers, in better health and living together( Reference Larrieu, Letenneur and Berr 30 ). Therefore, extrapolation of our results to the general population of elderly should be made with caution. The FFQ did not record quantitative data (portions, grams), but only frequencies of consumption. Low-frequency consumption does not necessarily mean lower energy intake, but simply suggests a lack of diversity in eating habits. Moreover, the FFQ did not allow calculating the total energy intake, as recommended to better control for confounding factors and to reduce extraneous variation( Reference Willett, Howe and Kushi 48 ). In a previous article exclusively on the population from the Bordeaux centre (n 1660) of the 3C study, daily energy intake was calculated in a sub-sample by using the 24-h dietary recall technique. In this sub-sample, daily energy intake was not affected by the frequency of consumption of fish, of fruits and vegetables (frequent v. less frequent) or by the use of n-3- or n-6-rich oils (regular v. non-regular)( Reference Barberger-Gateau, Raffaitin and Letenneur 49 ). Moreover, the baseline energy intake among the Bordeaux sub-sample was not significantly different between those who were dead (n 375) or still alive (n 1422) at the end of the 10-year follow-up (data not shown). This suggests that energy intake is not a major confounder in the present analyses. According to the literature, mainly studies with the most accurate data on food consumption (in daily amount)( Reference Osler and Schroll 3 , Reference Hamer, McNaughton and Bates 7 , Reference Bamia, Trichopoulos and Ferrari 15 , Reference Anderson, Harris and Tylavsky 16 , Reference Masala, Ceroti and Pala 18 , Reference Darmadi-Blackberry, Wahlqvist and Kouris-Blazos 20 – Reference Gillum, Mussolino and Madans 22 , Reference Streppel, Ocke and Boshuizen 43 , Reference Knoops, Groot de and Fidanza 46 ) found significant associations between dietary patterns and mortality. Our data did not allow this level of detail. However, our results confirm the benefit of several food categories on survival. Moreover, in our study, the assessment of dietary intake covered only broad food groups. This limitation is important for the interpretation of the association between meat and survival, because the meat group included both white meat (lean, healthy) and red meat (fat, deleterious). The limitations of the FFQ used in this study (few items, absence of validation, only baseline administration) could have led to non-differential misclassification bias. However, previous studies using this questionnaire have reported innovative results that are in agreement with the literature or have been successively confirmed by other independent analyses( Reference Larrieu, Letenneur and Berr 30 , Reference Samieri, Feart and Proust-Lima 34 , Reference Barberger-Gateau, Raffaitin and Letenneur 49 , Reference Berr, Portet and Carriere 50 ). Finally, in our sensitivity analysis including physical activity, only the association with fruits and vegetables remained significant. However, the variable physical activity did not rely on a detailed physical activities questionnaire, and these analyses were conducted in a limited sample (n 5273) reducing statistical power. The interpretation of this result is therefore limited.

Strengths of this study include the prospective population-based study design, with a large sample size, the completeness of the collected dietary data (data provided by >99 % of subjects, possibly due to the use of a simple and short questionnaire) and the low number of dropouts (0·1 %). Many variables were investigated as potential confounders, such as socio-demographic factors, health behaviours, BMI, drug use, self-rated health status and diet. The FFQ used in the 3C study has already allowed highlighting many interesting associations between diet habits and diseases( Reference Ritchie, Carriere and de Mendonca 31 , Reference Ritchie, Artero and Portet 33 , Reference Samieri, Feart and Proust-Lima 34 , Reference Barberger-Gateau, Raffaitin and Letenneur 49 – Reference Feart, Samieri and Rondeau 53 ). Chrysohoou et al.( Reference Chrysohoou and Stefanadis 13 ) insisted on the importance of taking into account socio-economic factors when considering the relationship between food habits and life expectancy, as healthy habits are associated with financial and educational status. In our study, we considered simultaneously education, occupation and income.

In conclusion, this study on the associations between dietary habits and mortality in a large population-based elderly cohort brings reliable evidence that could be used for developing nutritional programmes. Specifically, a diet with a daily intake of fruits and vegetables, regular consumption of fish, as recommended by the French Nutrition and Health Programme ( 26 ), and regular use of olive oil promoted longevity among an elderly community-living population. Diet quality is an important component of a healthy lifestyle that has beneficial effects on survival( Reference King, Mainous and Geesey 1 ). Additional studies should investigate the association between survival, diet and healthy behaviours, but this does not limit the importance of this simple public health message.

Acknowledgements

The 3C Study was conducted under a partnership agreement between the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), the Victor Segalen – Bordeaux II University and the Sanofi-Synthélabo Company.

The Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale supported the preparation and initiation of the study. The 3C Study is also supported by the Caisse Nationale Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés, Direction Générale de la Santé, Conseils Régionaux of Aquitaine, Languedoc-Roussillon and Bourgogne, Fondation de France, Ministry of Research-INSERM Programme ‘Cohortes et collections de données biologiques’, Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale, Institut de la longévité, Conseil Général de la Côte d’Or, Agence Nationale de la Recherche ANR PNRA 2006 and Longvie 2007 and Fonds de coopération scientifique Alzheimer (2009–2012).

F. L. formulated the research question, carried out the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data and drafted the manuscript. T. M., J. S., C. F. drafted/revised the manuscript; L.-A. G. carried out the statistical analyses and revised the manuscript; C. B. was involved in data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, study design, study supervision and drafting/revising of the manuscript.

There were no conflicts of interest for F. L., T. M., J. S., L.-A. G., C. B.; C. F. received fees for conferences from Danone Research and Nutricia.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1017/S000711451600266X