Introduction

Beginning in the last two decades of the 20th century, significant flows of migrants from Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe have attenuated the process of population ageing taking place in Southern European countries (Dalla Zuanna and Billari, Reference Dalla Zuanna and Billari2008). It is not surprising, therefore, that most of the political and scientific debate on the social integration of immigrants in these societies has focused on young adults (Ciobanu et al., Reference Ciobanu, Fokkema and Nedelcu2017). Furthermore, studies analysing the relationship between migration and care needs in later life have usually conceptualised migrants as (potential) care providers while neglecting their care needs (Bettio et al., Reference Bettio, Simonazzi and Villa2006; Walsh and Shutes, Reference Walsh and Shutes2013). As a matter of fact, despite their increasing number, relatively little attention has been paid to older migrants, their care needs and resources (Cela and Fokkema Reference Cela and Fokkema2017).

Intergenerational informal support is an important determinant of older individuals’ wellbeing, and a critical resource to cope with long-term care needs in later life (Klein Ikkink et al., Reference Klein Ikkink, van Tilburg and Knipscheer1999; Kang and Raffaeli, Reference Kang and Raffaeli2016; Albertini et al., Reference Albertini, Mantovani and Gasperoni2019). This is particularly the case in Southern European societies where the welfare system is characterised by a ‘familism by default’ approach (Saraceno and Keck, Reference Saraceno and Keck2011). In these countries, the availability of family care in old age represents a decisive factor in accounting for the wellbeing of older people, and can partly compensate the unequal distribution of formal care (Albertini and Pavolini, Reference Albertini and Pavolini2017). Migrants are usually in a disadvantaged position, vis-à-vis native individuals, in terms of the availability of informal care support in later life, because of the migration experience itself, their poor socio-economic situation, and the typically greater living distance between parents and children. Addressing these potential sources of inequality is becoming increasingly important (Dwyer and Papadimitriou, Reference Dwyer and Papadimitriou2006; Campomori and Caponio, Reference Campomori and Caponio2015; Cela and Barbiano di Belgioioso, Reference Cela and Barbiano di Belgioiosoin press).

Ageing migrants – especially deprived migrants from developing countries – are at risk of missing both relevant economic resources and much needed care resources. These higher risks are due to, among other things, their ‘otherness’ – which determines a lack of both provisions and rights, as well as ability to access public welfare (Warnes et al., Reference Warnes, Friedrich, Kellaher and Torres2004) – and to the social isolation that derives from the difficulty in relating to same-age individuals outside their own kin-network (Bolzman et al., Reference Bolzman, Fibbi and Vial2006; Cela and Fokkema, Reference Cela and Fokkema2017). In a nutshell, the ability of older migrants to cope with long-term care needs is likely to be reduced in all three relevant domains: individual capacities, social networks and formal social protection (Schröder-Butterfil and Marianti, Reference Schröder-Butterfil and Marianti2006).

As previous research has documented, the availability of informal support in later life is associated with the resources, structural opportunities and lifecourses characterising individuals and their families (Rappoport and Docquier, Reference Rappoport, Docquier, Kolm and Ythier J2006; Albertini, Reference Albertini2016). At the same time, family solidarity norms, and filial obligations in particular, play a significant role in determining the provision of care from adult children to their older parents, too. Cultural norms regulating such relations vary considerably both within and between different countries and ethnic groups (de Valk and Schans, Reference de Valk and Schans2008; Schans and Komter, Reference Schans and Komter2010; Silverstein and Attias-Donfut, Reference Silverstein, Attias-Donfut, Dannefer and Phillipson2010).

This article aims to shed light on the social norms regulating filial obligations towards older parents in Italy. More specifically, this article explores the social norms regulating the sharing of care-provision responsibilities – among children, other family members and institutions – and the type of support that is supposed to be given by adult children to their ageing parents; it also investigates the variation of these norms among four different groups: natives (born in Italy with both parents born in Italy) and immigrants (born in Italy or abroad to two foreign-born parents) hailing from Maghreb countries (Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria), the Philippines and China. The article is organised as follows: the next section sets the background to the study, reviewing findings from recent studies on the topic and describing the most salient characteristics of the groups considered in the analyses; the following section introduces the methodological aspects of the study. The results section reports the main findings of both quantitative and qualitative analyses, focusing on the sharing of care-provision responsibilities, also paying attention to the gender division of such responsibilities. The last two sections summarise and discuss the main limitations and empirical findings of the study, and suggest an agenda for future research.

Background: norms of filial support

The Italian context

Traditionally, in most societies, the bulk of work connected with providing care to older individuals who are not self-sufficient falls on to the shoulders of the family. More specifically, it is spouses and adult children who take over most of the duties connected with providing care support to these individuals (Bookman and Kimbrel, Reference Bookman and Kimbrel2011; Furstenberg, Reference Furstenberg2020). This is true not only for those societies in which the welfare system is absent or embryonic and where children represent an ‘insurance’ against risks related with old age (Kreager and Schröder-Butterfil, Reference Kreager and Schröder-Butterfil2004), but also in European societies with developed welfare systems in place. As a matter of fact, several studies have shown that adult children are highly involved in caring for their older parents, both in countries where a family-by-default approach is adopted – such as Mediterranean countries – and in Nordic countries, where the degree of defamilisation of care policies is the highest (Keck and Blome, Reference Keck, Blome, Alber, Fahey and Saraceno2008; Sarasa and Billingsley, Reference Sarasa, Billingsley and Saraceno2008; Saraceno and Keck, Reference Saraceno and Keck2011; Albertini, Reference Albertini2016).

If, on the one hand, filial obligations regarding older parents’ care needs are present and relevant in most societies, on the other hand, their strength, and the norms regulating who among the adult children should provide support, and how, vary between countries and across time. Italy – the national context of our study – is an interesting case. As pointed out in previous studies of family relations in Europe, Italy was (and still is) characterised by a relatively high level of intergenerational co-residence between adult children and older parents; this feature has been interpreted as an indicator of strong family ties and direct support provided by adult children to older parents (Laslett, Reference Laslett1988; Reher, Reference Reher1998). In the second part of the 20th century, however, the development of the pension and public health-care systems has made residential independence in later life increasingly common and a widespread social norm. Intergenerational co-residence is mainly utilised, instead, to provide support to young adult children before they leave the nest (Albertini and Kohli, Reference Albertini and Kohli2013). Among the middle and upper classes, and in those areas of the country where female labour market participation is the highest, the care needs of residentially independent older parents are usually met by a mix of family informal support, (relatively scarce) formal public home care services and nursing homes, and private market care services – often acquired by families on the grey labour market, employing immigrant women (van Groenou et al., Reference van Groenou, Glaser, Tomassini and Jacobs2006; Da Roit, Reference Da Roit2007; Sarasa and Billingsley, Reference Sarasa, Billingsley and Saraceno2008; Da Roit et al., Reference Da Roit, González Ferrer, Moreno-Fuentes, Moreno-Fuentes and Mari-Klose2015; Albertini and Pavolini, Reference Albertini and Pavolini2017). Thus, while norms of filial obligations are comparatively strong in Italy (versus other Western European countries), the way in which support is provided – and the extent to which there is a social acceptance that help provided by adult children is complemented by help acquired on the market – is rapidly changing, especially among the middle and upper classes. Furthermore, in a similar way but to a greater extent than observed in other European societies or the United States of America (USA), in Italy the division of elder-care work is quite gendered: older parents’ care needs – especially when personal care is needed and no spouse is available – are more frequently fulfilled by daughters than sons. In other words, when other providers are not available, sons are more likely to pass the burden of providing intense personal care on to the shoulders of their sisters, whereas they do not appear to share such responsibility with their female partners (Grigoryeva, Reference Grigoryeva2017; Luppi and Nazio, Reference Luppi and Nazio2019).

Migration and norms on social support

Theoretical models and empirical evidence reported in previous studies suggest that norms of filial obligation tend to be stronger among immigrant-origin families than native ones. According to the ‘family change’ model (Kagitçibasi, Reference Kagitçibasi2005; Kagitçibasi et al., Reference Kagitçibasi, Ataca and Diri2010), most migrants to Europe are moving from a collectivistic to an individualistic culture and family system. The former is characterised by a strong practical and emotional interdependence between family generations, whereas individualistic European societies stress emotional interdependence and practical independence and self-reliance. According to the theory of ‘family change’, migrant families bring with them collectivistic values and attitudes that price filial support obligations at a higher level than in the society of arrival. Previous studies also refer to other micro-level social mechanisms that could explain higher levels of functional and normative solidarity among migrant families: the experience of migration itself; the loss of non-kin networks when moving from origin to destination country; the experience of discrimination; and the desire to pass on the traditions and culture of the country of origin. All these mechanisms contribute to reinforcing family bonds. A different hypothesis is that the migration process causes an acculturation gap between first-generation migrants and their descendants; in turn, this could increase family conflict and diminish family solidarity. This latter hypothesis, however, has not found consistent support in recent empirical studies (Albertini et al., Reference Albertini, Mantovani and Gasperoni2019; Baykara-Krumme and Fokkema, Reference Baykara-Krumme and Fokkema2019).

To the best of our knowledge, studies comparing norms of filial obligations between natives and specific immigrant groups are relatively scarce, and based mainly on data from the USA and Northern European countries. In general, the existing empirical evidence suggests that feelings of obligation and indebtedness towards older parents are higher among migrant adult children than among natives. Their stronger norms of filial obligation are also mirrored by migrant parents’ higher expectations regarding the support they will receive from their children when they become old and frail (Burr and Mutchler, Reference Burr and Mutchler1999; Nauck and Suckow, Reference Nauck and Suckow2006; de Valk and Schans, Reference de Valk and Schans2008; Schans and Komter, Reference Schans and Komter2010; Kang and Raffaeli, Reference Kang and Raffaeli2016; Albertini et al., Reference Albertini, Mantovani and Gasperoni2019). Furthermore, while some previous analyses have found that second-generation migrants tend to adapt to the prevailing family solidarity norms of the country of arrival (Silverstein and Chen, Reference Silverstein and Chen1999; Ajrouch, Reference Ajrouch2005), other studies report that intergenerational family solidarity is stronger among immigrants than among stayers and natives, thus documenting a reinforcement of solidarity associated with the migration process (Cela and Fokkema, Reference Cela and Fokkema2017; Baykara-Krumme and Fokkema, Reference Baykara-Krumme and Fokkema2019).

If we shift our attention from solidarity norms to actual instrumental support and co-residence, we notice that structural constraints, needs and resources – and in particular the lack of economic resources, and greater living distance between generations – significantly affect support exchange between parents and adult children in migrant families. Older migrant parents are more likely than natives to receive financial support from their adult children – partly because they do not qualify for a pension in their origin or destination country and because of their worse economic situation. At the same time, a lower percentage of adult immigrant(-origin) children provide social support to their parents than natives. However, this is mainly due to the fact that many of them live in different countries and thus have transnational families. As a matter of fact, once distance is controlled for, it emerges that immigrant(-origin) children are more likely to provide support to their older parents than natives (Albertini et al., Reference Albertini, Mantovani and Gasperoni2019).

Besides these general patterns, previous studies also indicate that relevant variations in family solidarity norms are to be found not only between migrants and natives, but also among groups of migrants from different countries of origin. Because of data limitations, these latter differences have rarely been analysed in previous research. It would be a mistake, though, to assume that immigrant(-origin) people form a homogeneous group: each national group has its own norms, values and cultural traits (Albertini et al., Reference Albertini, Mantovani and Gasperoni2019).

Family solidarity among Chinese, Filipino and Maghrebi populations

Filial piety (xiao) is a relevant principle governing intergenerational relations among the Chinese population. Xiao is rooted in the Confucian tradition and refers to the child's obligation to respect, support and take care of older family members – especially parents and in-laws (Ikels, Reference Ikels2004). The obligation is based on the principle of reciprocity and framed into a representation of children as ‘insurance’ against risks related with old age (Kreager and Schröder-Butterfil, Reference Kreager and Schröder-Butterfil2004): the saying ‘Yang Er Fang Lao’ means that a primary purpose of raising children is so that parents can depend on children when they become older. Filial piety is thoroughly embedded in Chinese cultural and religious values, and is reinforced by governmental regulations as well, including in the China People's Republic Constitution. Schematising, Chinese values and cultural norms on filial support typically: (a) bestow greater responsibility to provide care for older parents on sons; (b) attribute practical and emotional support to daughters (Zhan and Montgomery, Reference Zhan and Montgomery2003; Song and Feldman, Reference Song and Feldman2012); (c) expect that a daughter-in-law assists her husband in caring for his parents (Guo, Reference Guo1996; Ci, Reference Ci2000).

It is not surprising, therefore, that the rich and flourishing literature on intergenerational relations among migrant-origin Chinese families has repeatedly documented that adult children tend to display quite strong norms of filial obligations vis-à-vis native children (Fuligni et al., Reference Fuligni, Tseng and Lam1999; Forrest Zhang, Reference Forrest Zhang2004). Children, especially the first-born son, are seen as an essential source of economic and social support in later life (Chen and Silverstein, Reference Chen and Silverstein2000; Sun, Reference Sun2002; Zimmer and Kwong, Reference Zimmer and Kwong2003; Thang, Reference Thang, Dannefer and Phillipson2010; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Chi and Silverstein2012). The normative support for and practice of intergenerational co-residence – as a form of help from adult married sons to older parents – is also widespread (Ofstedal et al., Reference Ofstedal, Knodel and Chayovan1999).

In the Philippines, older people have historically been dependent on children. Utang na loób (a debt of gratitude or debt-of-will) is a Filipino cultural trait according to which children are expected to provide care and assistance to their parents in old age (Dolan, Reference Dolan1991; de Guia, Reference de Guia2005; Reyes, Reference Reyes2015). This debt of gratitude is particularly strong towards the mother:

children are expected to be everlastingly grateful to their parents not only for all the latter have done for them in the process of raising them but more fundamentally for giving them life itself. The children should recognize, in particular, that their mother risked her life to enable each child to exist. Thus, a child's utang na loób to its parents is immeasurable and eternal. (Holnsteiner, Reference Holnsteiner, Lynch and de Guzman1973: 75–76)

As regards actual transfers, financial support from adult children to older parents is widespread and represents the main source of support for most individuals in later life (Hermalin, Reference Hermalin2002; Ofstedal et al., Reference Ofstedal, Reidy and Knodel2003). Intergenerational co-residence – with adult children taking turns in hosting their parents – is also a common strategy for coping with the care needs of elderly people. Interestingly, previous studies have documented that, in contrast to most other societies, norms regulating social support and actual distribution of support obligations are gender-neutral among Filipinos (Asis and Domingo, Reference Asis and Domingo1995; Natividad and Cruz, Reference Natividad and Cruz1997; Ofstedal et al., Reference Ofstedal, Knodel and Chayovan1999; Agree et al., Reference Agree, Biddlecom and Valente2005).

In most Arab countries, the family constitutes the main source of support in later life. Intergenerational support exchange within the family is built around the principles of kinship, paternal lineage and patriarchal bargain (Charrad, Reference Charrad2001; Yount and Sibai, Reference Yount, Sibai and Uhlenberg2009). In most Islamic communities, familial responsibility is a highly esteemed value, particularly regarding children's obligations to support their parents. The Qur'an – the primary source of Islamic law – states that:

Thy Lord hath decreed that ye worship none but Him, and that ye be kind to parents. Whether one or both of them attain old age in thy life, say not to them a word of contempt, nor repel them but address them, in terms of honour. And, out of kindness, lower to them the wing of humility, and say: ‘My Lord! Bestow on them thy mercy even as they cherished me in childhood.’ (Elsaman and Arafa, Reference Elsaman and Arafa2012: 11)

Men are usually expected to provide financial resources and women to uphold the kin group's collective interests. Co-residence remains one of the most relevant strategies – both in native countries and in countries of destination for migrants – to cope with the long-term care needs of older people. Since a traditional patriarchal kinship structure prevails in Islamic culture, older parents’ co-residence with their son and daughter-in-law is particularly widespread (Rassam, Reference Rassam1980; Aykan and Wolf, Reference Aykan and Wolf2000; Yount and Sibai, Reference Yount, Sibai and Uhlenberg2009; Schans and Komter, Reference Schans and Komter2010). In line with this pattern, previous studies of solidarity norms among Maghrebi-origin migrants living in Europe have found that filial support obligations are particularly strong among families hailing from Morocco, especially among first-generation migrants (Arends-Tóth and van de Vijver, Reference Arends-Tóth and van de Vijver2008; de Valk and Schans, Reference de Valk and Schans2008; Merz and Özeke-Kocabas, Reference Merz and Özeke-Kocabas2009; Rooyackers et al., Reference Rooyackers, de Valk and Merz2014).

Data and sample

As we have seen in the previous sections, the Italian context underlines the relevance of informal family support as a key determinant of wellbeing in later life. At the same time, prevailing social models are changing in the direction of: (a) prizing intergenerational residential independence; (b) prioritising children's emotional support and their involvement in less time-demanding care tasks; and (c) involving the contribution of paid care-givers in the welfare mix. On the other hand, results from previous studies suggest that, among migrant populations, we may find: (a) stronger norms of filial obligations, almost always involving direct care provision from adult children; and (b) frequent intergenerational co-residence. Nonetheless, a preliminary investigation of norms of family solidarity among the three ethnic groups considered here suggests that considerable variation is to be expected among the immigrant population too. By using original data drawn from a qualitative research survey carried out in Italy, the following analysis aims to shed light on the social norms regulating the sharing of care-provision responsibilities – among adult children, other family members, care-givers and institutions – and the type of help which is supposed to be given by adult children to their ageing parents. This article also aims to explore how these norms vary between and within the four groups here considered: native Italians and immigrants hailing from Maghreb countries, the Philippines and China.

The research was conducted in the province of Bologna, which is an interesting case study for the topic under investigation here. Bologna is located in the north-east of Italy, where: (a) immigration is a long-term phenomenon, which started at the end of the 1970s and is still continuing; (b) the presence of immigrant(-origin) populations is statistically relevant in both absolute and relative terms; and (c) the female employment rate among the native population is high and the patterns of family support towards elderly people have been changing rapidly since the second part of the 20th century. The survey was conducted through 493 face-to-face interviews. The sample consists of individuals selected among three diverse ethnic groups and native Italians; more precisely, it comprises: 144 Maghrebis (Moroccans, Tunisians and Algerians), 86 Filipinos, 119 Chinese and 144 Italians. Italians comprise individuals born in Italy with both parents born in Italy, whereas immigrant respondents have two foreign-born parents. The latter have also been classified according to the time spent in the receiving society as follows: (a) second-generation immigrants (G2) if they were born in Italy or arrived in Italy aged under 6; (b) 1.5-generation immigrants (G1.5) if they arrived in Italy aged 6-17; (c) first-generation immigrants (G1) if they arrived in Italy aged 18 or more. The survey was carried out through a snowball sampling technique – respondents were recruited among people living in Bologna: once a respondent was included in the study, other family members could not be interviewed. Since a non-probability sample design has been adopted, it is worth underlining that the data are not statistically representative of the immigrant or native populations. The sample sub-groups, however, reflect relatively well a number of socio-demographic characteristics of the adult population residing in the area under investigation (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic profile of sample sub-groups and corresponding reference population

Notes: Province-level data for the general population are not always available. For this reason, population data sometimes refer to wider territories (in which the province of Bologna is located), so comparison requires caution. 1. Population data refer to the Province of Bologna. Source: Istat 2015 (demo.istat.it). 2. Population data refer to people of 18 years of age and more residing in the Province of Bologna. Source: Istat 2015 (demo.istat.it) for Italians; Census 2011 (http://dati-censimentopopolazione.istat.it/Index.aspx) for Maghrebis, Filipinos and Chinese. 3. Population data refer to people aged 6 years and over, residing in Emilia-Romagna. Source: Census 2011 (http://dati-censimentopopolazione.istat.it/Index.aspx). 4. Population data refer to people residing in the province of Bologna for Italians and in Emilia-Romagna for Maghrebis, Filipinos and Chinese. Source: Census 2011 (http://dati-censimentopopolazione.istat.it/Index.aspx). 5. Population data refer to people aged 15 years and over, residing in Emilia-Romagna for Italians and in the north-eastern regions for Maghrebis, Filipinos and Chinese. Source: Census 2011 (http://dati-censimentopopolazione.istat.it/Index.aspx). na: not available.

Data collection was conducted through a questionnaire administered to respondents by trained interviewers. Most interviews with Maghrebis and Filipinos were conducted in Italian – while some were conducted in French, Arabic and English – whereas most interviews with Chinese respondents were conducted in their native language. The questionnaire included both a section with closed-ended questions aimed at gathering information on demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the respondents and their families, and a section with a set of vignettesFootnote 1 planned to capture norms about family intergenerational solidarity (Mantovani et al., Reference Mantovani, Gasperoni, Albertini, Gasperoni, Albertini and Mantovani2018). The vignette at the centre of this study intends to explore norms regulating support towards older parents by describing a situation in which an old and widowed mother has significant limitations in carrying out her personal and instrumental activities of daily living. Therefore, she is in need of practical help and care. In order to enhance its realism, the vignette identifies the hypothetical older mother and her adult children – one son and one daughter – with names that vary according to the respondent's ethnic origin. The text of the vignette is the following:

[Older woman's name] is an old widowed woman hailing from [respondent's country of origin] who has been living in Italy for many years. Footnote 2 She has two adult children [son and daughter's name], who live in the same city as her. Both her adult children are married and have two babies. [Older woman's name] is not healthy and has some limitations with daily living activities, such as: shopping for grocery and necessities, cleaning and maintaining the house, paying the bills, visiting the doctor, taking walks outside.

Respondents were asked: ‘What should [daughter's and son's names] do in order to help their old mother?’ The goal is to find the criteria used by respondents – and the underlying values and norms – in identifying who should help the older mother (offspring or other individuals), how adult children should behave and what type of support they should give to their mother. Respondents were discouraged from giving non-committal responses, i.e. ‘both adult children ought to help their mother to the same extent’. In such a case, the interviewer was instructed to ask which child – son or daughter – should have taken the main responsibility for helping the mother.

Analytical strategy

All discursive, open-ended answers were transcribed in full and analysed according to two dimensions: (a) who are the individuals (or institutions) that, according to the respondents, bear the main responsibility for helping the older mother; and (b) which support strategy is considered the most appropriate to assist the older mother among those who indicated adult children bore primary responsibility for providing care to the mother.

As regards the first dimension, several subjects were mentioned: adult children (split into the following categories: both adult children, mainly daughter, mainly son), care-giver, nursing home, extended family (other relatives excluding adult children); public welfare institutions or community organisations. The great majority of respondents (75%) mentioned just one subject, and this is more common among immigrant(-origin) people than natives (85% for Filipinos, 80% for Maghrebis, 79% for Chinese and 59% for Italians). In cases of multiple answers (23% of all respondents mentioned two subjects and only 2% indicated three subjects), subjects were ranked according to the priority given by the interviewee. The focus of the following analyses will be on the first and (partially) on the second most relevant support provider identified by the respondentsFootnote 3).

As far as the second dimension is concerned, various strategies of action were cited in the event that respondents mentioned ‘adult children’ as subjects responsible for the older mother. Strategies were classified in two macro-categories, which were further split into different dimensions. The first macro-category refers to the ‘co-residence of adult children with their mother’ and such a strategy is potentially implemented in three different ways: (a) shared co-residence: adult children take turns in hosting their older mother; (b) exclusive co-residence at daughter's house; and (c) exclusive co-residence at son's house. The second macro-category is ‘helping the older mother at her home’, and actual help is possibly given as follows: (a) equal distribution of care workload between son and daughter; and (b) exclusive care workload on the shoulders of the daughter. In a few cases (27 out 388 respondents) multiple strategies were reported; the following analyses, however, only take into consideration the strategy mentioned first.

Who should help the older mother?

Adult children, private care-giver, community or public welfare?

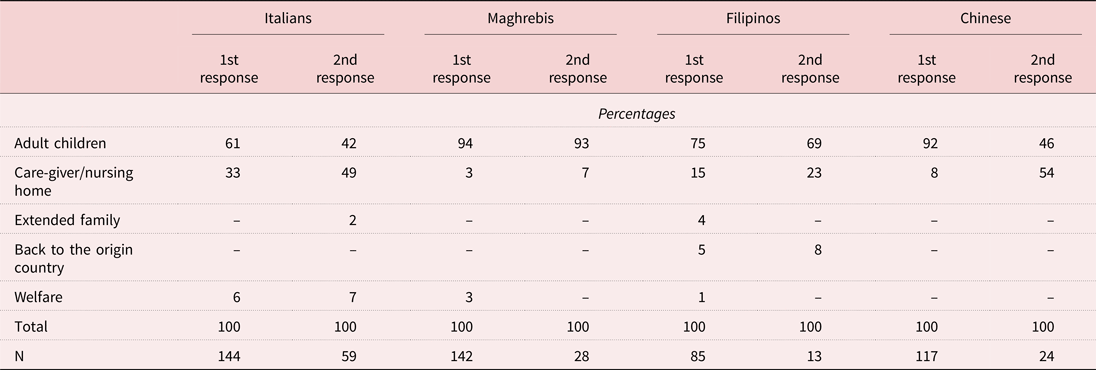

As far as the help provider (who) is concerned, most respondents (75%) identify just one preferred solution, 23 per cent give two options, whereas only 12 cases (2%) indicate three different potential providers of support. The great majority of interviewees state that adult children should support their mother in her daily living activities and this applies to respondents of any ethnic background (Table 2). Nonetheless, some interesting differences are detectable among the sub-groups. Maghrebi and Chinese respondents are the most likely to prioritise adult children as the main providers of support (94 and 92%, respectively), and only a small proportion of them take into account an alternative choice outside the nuclear family, such as hiring a care-giver or opting for the mother's admission to a nursing home (3 and 8%). Nonetheless, the rejection of resorting to formal, paid care is stronger and more systematic among Maghrebis than Chinese: the former also exclude the option of resorting to a care-giver or nursing home when indicating a second-best solution to meet the mother's care needs.

Table 2. Who should help the older mother by sub-groups: first two responses

Furthermore, respondents’ statements reveal that important differences lie behind these similar answers. In fact, the reason why help from public institutions or professional care-givers is rejected systematically varies according to the ethnic background. The ‘myth of the abandoned elderly’ prevails among Maghrebis, who consider the older mother's admission to a nursing home to be amoral behaviour against their deeply rooted social, cultural and religious norms (Hussein and Ismail, Reference Hussein and Ismail2017), whereas Chinese respondents are more likely to exclude involving a care-giver for financial reasons than for cultural and ethical ones; they also have a higher propensity to suggest hiring someone because they lack time to devote to taking care of the mother. This result may be explained by the fact that many Chinese immigrants – especially women – belong to the sandwich generation: they are squeezed between care obligations towards the younger and older generation (Falkingham et al., Reference Falkingham, Evandrou, Quin and Vlachantoni2020; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Feng and Jiang2020).

Taking care of parents is not only a matter of Islamic law, but it is a wider precept embedded in the Moroccan culture. It is unimaginable to abandon one parent on his/her own, we would never consider admitting him/her to a nursing home. (Maghrebi, male, 29 years old, G1)

In Italy it is quite common to admit an old parent to a nursing home, but in the Muslim culture it is judged as an immoral practice, because it means that a son/daughter does not appreciate his/her parents and is not grateful for all the efforts they did to raise their family. (Maghrebi, female, 34 years old, G1)

The old mother lives in her own home … and if they [adult children] have money, they can hire a care-giver. (Chinese, male, 25 years old, G1.5)

If adult children do not have time to take care of their older mother, because they have to look after their babies, they can hire a care-giver. (Chinese, male, 31 years old, G1.5)

Responses given by Filipino and Italian survey participants are more heterogeneous. Although they also think that adult children remain the main actors responsible for helping the older mother, these respondents are more likely to indicate that adult children should seek the support of a care-giver or their mother's admission to a nursing home (33 and 15%, respectively). Resorting to a care-giver/nursing home is seen as a legitimate and blameless choice, with the main limitation being that of the availability of sufficient economic resources:

Admission to a nursing home is impossible, because it is too expensive in Italy. (Filipino, female, 52 years old, G1)

[The adult children] should hire a care-giver, because if they have their own family and are employed, they won't be able to spend time with their old mother. (Filipino, female, 18 years old, G2)

The adult children do not have time to spare, because of their domestic and working commitments. If their mother had financial resources, they should hire a care-giver … or, better, admit her to a nursing home, because a care-giver is an untrustworthy person. (Italian, female, 73 years old)

This finding is consistent with previous research, which stresses that financial resources matter: families with higher socio-economic status are less likely to provide direct care and are more prone to purchase elder-care services (van Groenou et al., Reference van Groenou, Glaser, Tomassini and Jacobs2006; Sarasa and Billingsley, Reference Sarasa, Billingsley and Saraceno2008; Albertini and Pavolini, Reference Albertini and Pavolini2017).

Italian interviewees also emphasise how positive and twofold the effect of hiring a care-giver may be. On the one hand, the older mother will not be forced to leave her home and might preserve her habits and go on living her life in whatever way she pleases. This aspect is not trivial at all, since most older people want to live in their own home and there is a quite widespread assumption that there is a positive relationship between housing and wellbeing among elderly people (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Kantrowitz and Eshelman2002; Pinquart and Burmedi, Reference Pinquart, Burmedi, Wahl, Scheidt and Windley2004): ‘the home environment is the domain in which daily routines and practices are given personal meaning by reference to personal biography’ (Rubinstein et al., Reference Rubinstein, Kilbride and Nagy2005: x):

The adult children could help their mother by paying a person of trust, who can relieve her from the burden of daily activities … I believe that letting the old mother have her independence, in her own home with the help of a care-giver, is the best solution. (Italian, female, 35 years old)

On the other hand, hiring a professional care-giver also allows adult children to satisfy many conditions at the same time, such as: (a) guaranteeing support for their frail older mother without abandoning her in a nursing home; (b) limiting the burden of their filial obligations; (c) preserving their wellbeingFootnote 4; and, last but not least, (d) maintaining their own lifestyle:

The adult children should hire a care-giver. This solution would be the best one, since both the mother and her adult children can retain their independence and freedom. (Italian, female, 64 years old)

The preservation of adult children's residential independence and resorting to the market may appear to be a sign of weakening intergenerational family solidarity: the older mother's needs are satisfied by a professional care-giver and adult children may be exempt from their filial care obligations for the aged. Nonetheless, this is only one way of looking at this transformation of norms of family solidarity. Externalisation of care services can also be seen as a strategy for both safeguarding family wellbeing and strengthening intergenerational ties (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen2009). In fact, even if hiring a professional care-giver – who gives an older parent practical assistance daily (personal care, physical activities, cleaning and maintaining the house) – may be a relief for adult children, this option does not necessarily crowd out a family's informal support and does not necessarily undermine familial emotional support. Indeed, adult children may reallocate their (still) available spare time to investing in preserving a sentimental bond with their frail older mother, i.e. going to visit her and keeping her company (Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Haberkern and Szydlik2009):

I think that [hiring a care-giver] is the best solution, because it guarantees the mother's dignity: the older woman lives in her own little home and a cleaning lady might take care of her, whereas adult children may go to visit her. (Italian, male, 51 years old)

The selection of a care-giver/nursing home also calls into question who should organise and pay for this professional service. Respondents of all ethnic groups have no doubts about who should arrange such professional help: adult children. As regards the care-giver's payment, even if a relevant minority (one out of three respondents) does not specify on whom the cost should fall, the majority (approximately six out of ten interviewees) state that the expenditure should be divided equally between adult children, whereas the financial burden is sporadically charged to the mother.

A number of Maghrebi and Italian respondents also mention that resorting to public welfare services or non-governmental community-based service providers may be a socially accepted and good option:

They [adult children] should seek local social services’ help in order to provide the older mother with daily practical support. (Italian, male, 59 years old)

There are voluntary associations which can help the older mother as regards most daily practical activities, such as doing the shopping, buying medicines, accompanying her to a doctor's appointment. The adult children should exploit these social services … so they can spend their spare time in keeping her company. (Italian, male, 63 years old)

They [adult children] have to get in touch with the local authority and ask for a social worker … in fact, a sick and frail older person is legally entitled to be assisted by a welfare worker paid by the welfare state. (Maghrebi, female, 41 years old, G1)

The number of respondents who mentioned the role of public welfare policies in helping children meeting the old mother's care needs is quite small. Thus, sharing responsibilities between family and public welfare services is a solution cited by just 6 per cent of Italian respondents. The possibility of resorting to public services is even less frequently cited by non-native interviewees, probably also due to the fact that they are less familiar with existing welfare policies both at the local and national level. In particular, 3 per cent of the Maghrebi respondents – especially Moroccans and first-generation immigrants – suggest seeking support from public welfare institutions. Among Chinese respondents, no one refers to this alternative, and this may depend on the fact that Chinese people are either particularly ill-informed of what to do in order to apply for public care services and support in Italy, or are not used to turning to social services for care for elderly people due to the limited availability of these in China (Gu and Liang, Reference Gu, Liang, Bengtson, Kim, Myers and Eun2000; Zhang and Goza, Reference Zhang and Goza2006; Albertini and Semprebon, Reference Albertini and Semprebon2018). Overall, these results suggest that the sharing of responsibilities between family members and public institutions is very rarely mentioned as an optimal solution – much less frequently than resorting to a mix of support from family members and a private care-giver – and this is even more so among immigrant groups.

A small number of Filipino respondents mentioned a different solution to meeting the care need of the older mother: returning her to the country of origin and/or resorting to the help of other relatives:

If they [adult children] have relatives in the Philippines, they should send the mother back to the Philippines because taking care of her in Italy is very difficult, very expensive. (Filipino, male, 47 years old, G1)

They [adult children] should repatriate the mother and pay a relative to look after her there. In Italy, adult children cannot take care of her, because they have their own families. (Filipino, female, 41 years old, G1)

A good solution is to ask for help to all relatives of 12 years of age and more. Everybody should co-operate to support the older mother. (Filipino, female, 22 years old, G2)

A lack of financial resources and/or shortage of time to dedicate to the older mother are the most common reasons mentioned by Filipino respondents in order to justify the option ‘take the mother back home’. Nonetheless, additional plausible explanations to this alternative might be found either in the so-called ‘salmon effect’ – return migration is more likely if migrants’ health conditions deteriorate (Abraìdo-Lanza et al., Reference Abraído-Lanza, Dohrenwend, Ng-Mak and Turner1999; Palloni and Arias, Reference Palloni and Arias2004) – or in the lack of co-ethnic social support in the country of destination (Bolzman et al., Reference Bolzman, Fibbi and Vial2006).

Respondent's gender, age and immigrant generation: do they make any difference?

Although it is necessary to bear in mind that caution is required when using data collected through a non-probabilistic sample design, Table 3 does not suggest any noteworthy differences related to respondent's gender at the moment of selecting who has the main responsibility of taking care of an older mother. In other words, men and women seem to be following the same filial obligation norms towards the older mother, and differences are related more to their ethnic background.

Table 3. Who should help the older mother by sub-groups, gender and immigrant generation: first response only

Notes: G1: arrived in Italy aged 18 or over. G1.5: arrived in Italy aged 6–17. G2: arrived in Italy aged under 6 or born in Italy.

On the contrary, interesting dissimilarities are associated with respondents’ age and, among immigrants, the time spent in the receiving country (that is, immigrant generation).

The respondent's age is an important dimension along which variation in norms of family solidarity can be observed. As a matter of fact, age is a good proxy of the individual's lifecourse and, thus, of his or her subjective situation in terms of the care needs or obligations he or she is embedded into at the moment of the interview. As far as respondent's age is concerned, Italians and Maghrebis display similar patterns: younger interviewees are more prone to indicate that adult children are in charge of providing care to the mother than respondents of the same ethnic group but older age. The opposite gradient is detectable among Filipino and Chinese respondents: the eldest interviewees are more in favour of resorting to the help of adult children and less inclined than younger generations to search for help in the private market of care services.Footnote 5 In other words, an individual's position in the lifecourse appears to be correlated with the idea of who should bear the primary responsibility for providing help to an older parent, but age plays a different role in the four different groups considered.

As regards immigrant generation, Filipino and Chinese respondents born in Italy or arrived before the age of 6 (G2) are less likely to mention adult children as being responsible for the old mother than their first-generation compatriots, whereas the former exclude to a lesser extent the care-giver/nursing home option. In other words, norms regulating filial support obligations seem to vary by generation of immigration, and second-generation immigrants (who have lived in the receiving country for longer periods of time) seem more likely to internalise natives’ values, norms and expectations about family relationships. This result suggests that some forms of acculturation may be in play and are shaping, to some extent, filial solidarity norms.

The role of adult children in supporting older parents: an (un)even burden?

Daughter, son or both?

As mentioned above, most respondents state that adult children should bear the main responsibility for providing care to the older mother. This finding is not unexpected, since unpaid family members are the predominant source of support for frail older parents (Wolff and Kasper, Reference Wolff and Kasper2006; Verbeek-Oudijk et al., Reference Verbeek-Oudijk, Woittiez, Eggink and Putman2014).

However, it is worth noting that even if filial obligations towards older parents are extensively rooted in most societies, adult children do not necessarily shoulder the burden of older parents equally.

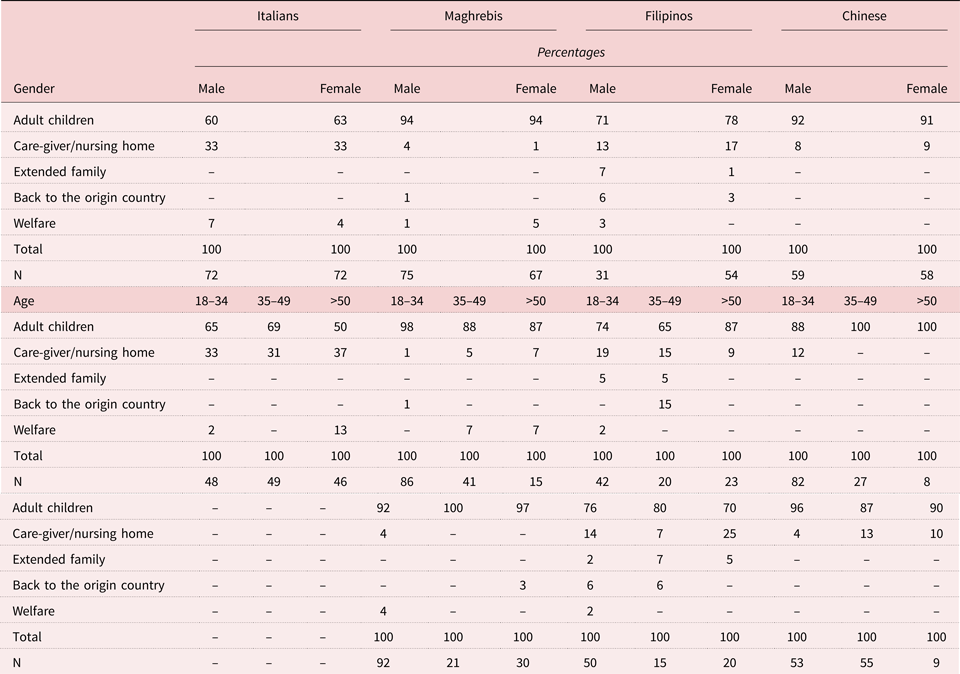

The results reported in Table 4 indicate that a large majority of respondents, across all groups, suggest that both adult children represented in the vignette – i.e. son and daughter – bear the responsibility of providing long-term care to their mother. Italian respondents almost unanimously support the equal sharing of care responsibility between son and daughter (99%), while this support tends to be lower among Chinese (87%) and, even more so, among Maghrebi and Filipino respondents (65 and 63%, respectively). When not supporting a gender-equal distribution of care responsibilities among adult children, Chinese respondents are more prone to identify the son as the main person responsible, Filipino respondents are more likely to suggest the daughter has the main responsibility, while Maghrebi respondents are split almost equally between the two. Prima facie these results suggest that: (a) a gender-balanced division of filial care obligations is widespread across all the four ethnic groups; and (b) this support is particularly strong among Italian and Chinese respondents.

Table 4. Which adult children should help their older mother by sub-groups

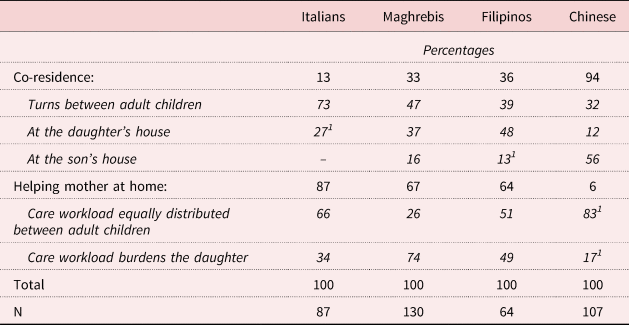

However, once strategies implemented to help the older mother are examined in depth, an evident gender bias comes into sight. As far as care strategies for elderly people are concerned, two possible options are mentioned: co-residence and helping the older mother at her home (Table 5). Co-residence of adult children and their frail older mother is (almost) the only choice according to Chinese respondents (94%), whereas Filipinos, Maghrebis and, especially, Italians are more likely to opt to help the older mother at her home (64, 67 and 87%, respectively).

Table 5. How should adult children help their older mother by sub-groups

Note: 1. Five cases at most.

Co-residence

Co-residence always implies that the mother moves in with one of her children, whereas the opposite solution (one child moves in with the mother) was never cited.

In the case of co-residence, if there were a perfect share of responsibilities between children, the older mother would rotate between children's households. This solution is hypothesised the most by Italian respondents (73%) – although one should bear in mind that a very low proportion of them indicated co-residence as the best strategy (13%), maybe because living very close to parents is hugely widespread in Italy (Glaser and Tomassini, Reference Glaser and Tomassini2000) – who often emphasise the relevance of gender equality in taking care of the older mother, and stress how important is the ending of the ‘sexual taboo’ to this purpose: sons, too, can assist a parent of the opposite sex with bathing and using the toilet:

They [adult children] should take turns at taking on the responsibility to host the older mother at their home … They must arrange to host their mother with no distinction between daughter and son, since nowadays there are no more reasons for embarrassment in assisting a parent of the opposite sex. (Italian, male, 45 years old)

Maghrebi, Filipino and Chinese respondents are less likely than Italians to opt for an equal rotation of the mother between the children's households (47, 39 and 32%, respectively) and, although they stress that ‘son and daughter have the same responsibilities’, they often mention specific conditions (i.e. job and financial constraints, family relationships, mother's will and house size) that should be taken into account when defining which child should bear the greatest burden of co-residence. In other words, time and/or the availability of financial resources are decisive features in allocating responsibilities between siblings:

Both adult children must help her. There is no difference between them. The only differences are associated with job workload and/or the quality of family relationships. (Filipino, female, 54 years old, G1)

If siblings maintain a good relationship, they will decide with which one of the two the older mother may co-habit. They can assess who has the biggest house and/or who has better financial health. Anyway, both adult children have the same responsibility, none of them can do less than the other one. (Chinese, female, 42 years old, G1)

They [adult children] can take turns or the one who lives in an adequate house may host the older mother. Daughters are usually more likely to host the older mother, since they have a stronger relationship with her. Nonetheless, if the daughter's house conditions are limited, the older mother may move in with her son. (Maghrebi, male, 54 years old, G1)

The latter narrative also introduces a popular element to examining obligations towards the older parents: the gender division of parent care among siblings and, more precisely, the social expectation that daughters are ‘natural’ care-givers. This narrative is present in a significant number of responses that, prima facie, indicate that son and daughter should share equally the burden of providing care to the old mother. An in-depth analysis clearly reveals that this gender equality is often a general principle within which quite biased gender-based principles are utilised to specifically identify which tasks should be performed by sons or daughters. The literature has stressed that sons and daughters play different care roles, and the latter more often co-habit with older parents when it comes to caring for them. This gender cleavage is more evident among Filipino (48%) and, to a lesser extent, Maghrebi respondents (37%):

The daughter must take care of her mother and satisfy her needs. This is what our culture teaches us, women are tender-hearted. When a mother is in need, she always asks for help from her daughter, not her son. Mothers are very devoted to sons, but when they age and need help, they will look for the daughter. The older mother should move in with the daughter, whereas the son should help her with money. (Filipino, male, 53 years old, G1)

The older mother should co-habit with her daughter. The daughter is a woman, she is more sympathetic, talkative … she is more capable of providing help, males are not patient. A daughter may take care better of a woman's needs, for example preparing meals, bathing, toileting, doing chores, shopping for groceries … Nonetheless, bills should be paid by both siblings. (Maghrebi, male, 28 years old, G1.5)

These findings confirm that ‘women are usually considered kin-keepers and more likely to take care of the parents in later life’ (de Valk and Bordone, Reference de Valk and Bordone2019: 1793) and, even if sons are not totally relieved of their care-giving role, their responsibility is above all limited to (non-time-consuming) financial help or less-demanding tasks such as paying bills or taking the mother to the general practitioner.

These results, however, are partially unexpected: previous studies have shown that norms of filial obligation among Filipinos are generally gender-neutral and that adult children are used to taking turns at hosting older parents in their homes whereas in Islamic culture a traditional patriarchal kinship structure prevails, which enhances older parents’ co-residence with their son and daughter-in-law. After all, a more accurate investigation of the Maghrebi respondents' answers reveals that men's authority is not at all undermined or underestimated in the case of the mother's co-residence with either her daughter or with her son:

In Morocco the older mother is used to moving in with her daughter, because the latter is more patient in taking care of the mother, whereas the son is a symbol of force and prestige. (Maghrebi, female, 39 years old, G1)

The old mother will have to move in with her son. He is responsible for his mother and his wife has to take care of her mother-in-law … The son … is also financially responsible for his mother. The daughter might have to take care of her mother-in-law. (Maghrebi, male, 23 years old, G1)

The son is better than the daughter. The son might have a good wife, whereas the daughter might have a husband who cannot stand the mother-in-law. (Maghrebi, male, 28 years old, G1)

These narratives well exemplify that Maghrebi sons/men are often deemed to be the unique ‘breadwinners’: they are financially and ethically responsible for their mother, whereas daughters/sisters/daughters-in-law – as women – must provide care to the older family members. These findings are consistent with traditional Islamic culture: the daughter-in-law occupies the lowest status and power position within her household. Modesty and obedience are highly desirable attributes in a daughter-in-law and taking care of the older mother-in-law is a duty (Rassam, Reference Rassam1980).

An (almost) absolute position of primary responsibility attributed to sons in providing care for the older mother is unequivocally traceable among Chinese respondents. Interviewees’ answers are congruent with Chinese values and cultural norms, which promote older parents’ co-residence with the eldest son (Zhang and Goza, Reference Zhang and Goza2006). The only exception we find, vis-à-vis this pattern, is that respondents almost unanimously agree that the older mother should live with her son, but also that the daughter has to contribute to the expenses as well:

[The older mother] lives with her son and his family. This is the Chinese tradition. The daughter-in-law has to help her in toileting, whereas the daughter has to take care of her own family. (Chinese, male, 44 years old, G1)

Traditionally, the older mother moves in with his son. Sons have more responsibilities in daily life. The daughter-in-law has to give assistance to her mother-in-law and the daughter has to take care of her mother as well. (Chinese, female, 47 years old, G1)

Son and daughter-in-law take care of the older mother and live together. Daughter often visits her mother and gives money to her. (Chinese, male, 22 years old, G1.5)

Helping the older mother at her home

If co-residence is the most common option selected by Chinese respondents, helping the older mother at her home is extensively preferred by the other three sub-groups, in particular Italians. According to the respondents, helping the older mother at her home satisfies both the value of reciprocity and the adult children's daily needs related to the dilemma of work–life–care balance and desire for residential independence:

Mom is everything and children have to sacrifice for her. They should take turns at mother's home: one child goes shopping, the other one cleans the house. They cannot abandon their parents … Both children have the same responsibilities … I mean that sons may also help their mother in toileting and bathing. (Maghrebi, female, 46 years old, G1)

Parents sacrifice themselves for children's benefit and later children have to strive for their parents. In this situation, both adult children must help their older mother doing chores at her home. (Filipino, male, 46 years old, G1)

Both adult children must help their mother at her home. They should take into account their time availability and take turns in doing the same efforts. I believe this is the right thing to do, because the mother had raised them for a long time and now it's time for children to care for her. (Italian, male, 39 years old)

Although most respondents state that both adult children have to help their mother equally, gender bias dies hard. An even distribution of responsibilities between adult children is just initially declared, but a clear gender divide often emerges immediately after the first statement:

They [adult children] should help their older mother in the same way and fulfil duties on the basis of their skills: female duties for the daughter, such as cleaning the house, bathing, chatting and keeping company … and male duties for the son, such as managing finances, visiting the doctor… (Maghrebi, male, 34 years old, G2)

This answer well exemplifies the idea that siblings shoulder the care-giving burden very differently. Sons and daughters stick to the script: the former are expected to provide monetary support or run errands, whereas the latter are deemed responsible for helping older parents with emotional support and personal care. This gender specialisation of duties is particularly evident among Maghrebi respondents: 74 per cent report that daughters should bear the burden of the majority of care duties (against 49% of Filipinos and 34% of Italians). Nonetheless, it is important to stress that Maghrebi males are more in favour of this gender imbalance than their female compatriots: among 23 respondents sympathetic with an uneven distribution of care-giving burden, more than half (56%) are male, whereas among 64 interviewees encouraging no gender bias, six out of ten (61%) are female.

It is worth noting, however, that even if helping the older mother at her home is the most frequent form of support mentioned by all sub-groups (except for the Chinese respondents), this option is often conditioned to the mother's health situation and to the time constraints faced by her children. It is quite common for respondents to state that adult children should help the older mother as long as her needs are compatible with their work and family lives:

The siblings should take turns to help their old mother, since she prefers to be assisted by her children. But if this option couldn't be pursued, they should hire a professional care-giver. (Italian, female, 48 years old)

The adult children are married, have a job and have two babies … if they don't have enough time to dedicate to their mother, they should hire a care-giver. (Maghrebi, female, 41, G1)

In other words, helping the mother at her home seems to be just a temporary option, until her health further deteriorates, and alternative solutions are contextually taken into account as well. The most frequently mentioned alternative option is hiring a professional care-giver; this arrangement does not seem to break any social norms of reciprocity. Resorting to formal care-givers does not necessarily plague adult children with the social stigma of abandoning their older and frail parents, but this exemption is possible only if this option is pursued at a later time and adult children do not have time available to sustain the burden of care towards the older mother.

Discussion

In recent decades a significant influx of immigrants to Southern European countries has contributed to counteract the progressive ageing of the native population. Most of the scientific literature on the topic has focused on the processes of social and economic integration of young adult migrants into the societies of arrival. Migrants, especially women, have also been studied as a relevant source of formal care for coping with the increasing care needs of an ageing population – a demand that has not been met by a corresponding increase in public care services (Bettio et al., Reference Bettio, Simonazzi and Villa2006). Given this picture, it is not surprising that the progressive ageing of immigrants and their long-term care needs have often been overlooked in previous sociological studies.

In line with what has been observed for the native population, the wellbeing of older migrants living in Southern European countries is largely dependent on the quality and quantity of the informal care they receive from their families and kin network (Albertini and Pavolini, Reference Albertini and Pavolini2017). As a matter of fact, in a welfare system based on a familism-by-default approach, individuals strongly rely on care provided by children and spouses for their long-term care needs. Immigrants’ resources, in this respect, may be limited in all the three relevant domains: individual capacities, social networks and formal social protection (Schröder-Butterfil and Marianti, Reference Schröder-Butterfil and Marianti2006).

In this article, we have begun to explore the norms of filial obligations towards older parents, comparing Italian natives with three immigrant-origin groups – from the Maghreb, China and the Philippines. The analysis has identified several commonalities across the four groups, but also relevant differences – not only between natives and immigrants, but also among the various immigrant groups. In addition, important differences in norms of family solidarity may be observed within the same ethnic group as well (e.g. among individuals at different points of their lifecourse and/or belonging to different immigrant generations).

Common to all four ethnic groups is that a large majority of respondents indicate that adult children are responsible for providing long-term care support to an older widowed mother. In other words, a strong or complete defamilisation of support obligations is not on the horizon in the Italian social context. However, the extent to which this social norm is largely majoritarian, or not, varies across the four groups. Among Italian respondents, almost one-third indicate that the optimal solution for meeting the mother's care needs is to hire a care-giver, whereas this social norm is shared by a much lower proportion of respondents with immigrant origin. In particular, 15 per cent of Filipino, 8 per cent of Chinese and just 3 per cent of Maghrebi respondents mentioned resorting to a care-giver or a nursing home as the most adequate solution. It is worth noting, however, that a significant quota of Chinese (54%) and Filipino (23%) respondents indicate this option as the second-best solution, thus suggesting that they are not completely averse to seeking professional help to support older, frail parents. Maghrebis, on the other hand, clearly stand out as the group with the greatest aversion to non-family-based solutions to the provision of care; in their view, family still constitutes the main source of support in later life (Charrad, Reference Charrad2001; Yount and Sibai, Reference Yount, Sibai and Uhlenberg2009).

According to Italian interviewees, resorting to private care services has several advantages, such as: preserving adult children's and older parents’ lifestyle; relieving adult children of stress in coping with multiple and competing demands (i.e. raising their own young children, fulfilling their job duties); and increasing the opportunity to focus on the provision of emotional support. On the contrary, the respondents most adverse to this solution consider resorting to formal and paid care as a violation of the social norms and religious prescriptions regulating filial obligations towards older parents. Among Maghrebis, in particular, the rejection of professional care is a matter of not ‘abandoning the elderly’, which would imply a violation of a moral norm/obligation generating social disapproval and/or personal psychological distress (Axelrod, Reference Axelrod1986).

The results also reveal that the issue of who is responsible for the older mother is quite complex and ethnic origin only partially explains differences in attitudes and behaviours. In fact, if respondents’ age – a proxy of the individual's position in their lifecourse – is taken into account, interesting nuances are noticeable. Even if resorting to adult children remains considerably more widespread among the three immigrant groups than natives, older Maghrebis and Italians display a similar lower hostility towards formal care services, whereas older Chinese and Filipinos seem to have more deeply internalised the idea that children owe a debt of gratitude towards their parents and privilege the traditional value of relying on adult children. The time spent in the receiving country (that is, immigrant generation) also seems to play an interesting role in shaping values of filial obligations. Filipino and Chinese respondents born in Italy or arrived in Italy before the age of 6 (G2) are less likely to mention adult children as responsible for the older mother than their first-generation compatriots, and exclude the care-giver/nursing home option to a lesser extent. In other words, the longer immigrants livein the country of destination, the greater the internalisation and acceptance of the native population's norms is: a process of adaptation to the dominant group seems to be in play. These findings suggest that an intersectional approach is required to examine (and understand better) the relationship between family solidarity norms and behaviours. Indeed, additional dimensions (such as gender, age, time spent in the receiving country, social class, etc.) may explain why different social norms are internalised by immigrants, regardless of ethnicity.

As regards the actual strategy that adult children ought to implement to take care of the older mother, interviewees mainly refer to two possibilities: co-residence with the older mother or helping the frail mother at her home. The results reveal a cleavage between the Chinese and other groups. The filial piety principle is still extremely embedded in Chinese people's cultural values and their behaviour is consistent with it, since almost all respondents prefer the intergenerational co-residence option, whereas co-residence is selected as the favourite strategy by about one-third of Maghrebi and Filipino respondents and a very small minority of Italians. In other words, Maghrebis and Filipinos are more likely to help their older mother at her home. To some extent, this finding is at odds with their culture and social norms, which promote co-residence with older parents as a value and a duty (Rassam, Reference Rassam1980; Asis and Domingo, Reference Asis and Domingo1995; Natividad and Cruz, Reference Natividad and Cruz1997; Ofstedal et al., Reference Ofstedal, Knodel and Chayovan1999; Aykan and Wolf, Reference Aykan and Wolf2000; Agree et al., Reference Agree, Biddlecom and Valente2005; Yount and Sibai, Reference Yount, Sibai and Uhlenberg2009; Schans and Komter, Reference Schans and Komter2010).

Even if adult children are deemed to bear the main responsibility of providing care to older parents, and prima facie in all of the four groups the majority of the respondents endorse gender-equal sharing of care responsibilities, in-depth qualitative analyses reveal that norms regulating the sharing of the care burden between siblings are far from being gender-neutral. For instance, most Chinese respondents indicate that the son is the main person responsible for hosting the older and frail mother at his home, but the son's wife actually has the responsibility of providing personal care to her mother-in-law. Among the other three groups – including Italians – the general principle of equal sharing of responsibility goes hand-in-hand with norms prescribing gender-specialisation in care provision. Sons are seen as responsible for providing support with paperwork, household chores, shopping, buying medicines and visiting the doctor. But, according to these norms, the daughter(-in-law) has to take up the most physically, psychologically and time-demanding aspects of care support, i.e. helping with personal care and daily living activities. This gender imbalance is more pronounced among Maghrebi respondents than among the Italian and Filipino ones. This finding is consistent with previous research: Filipino's norms regulating social support are more gender-neutral, whereas Islamic culture promotes a patriarchal kinship structure.

Conclusions

In general, the results of the analysis presented in this article stress that the burden of providing care to older parents still predominantly weighs on adult children's shoulders, regardless of their native or non-native status, or their ethnic origin.

Despite this general commonality, immigrants are more likely than Italians to indicate adult children as being primarily responsible for providing help to an older frail mother. In particular, the filial piety principle – rooted in the Confucian tradition – is still strongly embedded in the Chinese community: (a) children must provide help to older parents; (b) daughters(-in-law) must bestow practical and emotional support; (c) sons are expected to be responsible for older parents’ financial support; and (d) co-residence (at the son's house) is almost the unique feasible strategy to help the older mother.

Intergenerational support – based on the principles of kinship and patriarchal bargain promoted by Islamic culture – is also crucial among Maghrebis. This immigrant group has some similarities with the Chinese immigrant population: (a) adult children are the primary source of help; and (b) an evident gender imbalance affects the distribution of responsibilities between sons and daughters(-in-law). Nonetheless, even if co-residence is traditionally the most common strategy implemented by adult children to help their older parents, results reveal that most Maghrebi interviewees have a preference for helping the older mother at her home, and this strategy is shared with most of the Filipinos and Italian natives as well.

Finally, Filipino immigrants are characterised by the lowest level of rejection of the idea of resorting to a professional care-giver (or a nursing home) as a feasible and not deplorable option to help the older mother. In this aspect, Filipinos are more similar to Italian natives. Furthermore, Filipinos differ from the other immigrant groups in that they are more in favour of a gender-equal distribution of care responsibilities; this attitude is quite consistent with their tradition and values.

This study represents an important effort to explore which norms of filial obligations towards older parents govern immigrants’ behaviour according to their ethnic origin, and whether their culture and values are reinforced (or not) by their immigrant status. Undoubtedly, further surveys should be carried out in order to understand norms ruling filial obligations better; some limitations of the current study need to be overcome.

The three most relevant limits are: (a) the absence of external validity (due to non-random sampling procedures); (b) the local context in which the survey was carried out; and (c) the analysis of just one vignette to explore this complex issue. The latter limitation, in particular, puts into question the reliability of our findings in terms of the norms regulating the gender division of care obligations and the role of public institutions: Would we have obtained the same pattern of responses if we had applied a vignette featuring the story of a frail older father, instead of a mother? Would the answers have been different if additional elements – referring to the availability of public policies – were added to the vignette? Obtaining a representative sample of the population and increasing the set of vignettes utilised are two important directions along which future studies of the topic should invest additional efforts.

At the same time, the present study sheds light on why future analyses of care support in later life should address not only the actual patterns of functional support among native and immigrant populations, but should also focus specifically on support norms across the different ethnic groups within the immigrant population. Furthermore, the results show the need to adopt an intersectional approach: examining differences across key individuals’ socio-demographic characteristics – such as, for example, gender, age and time spent in the receiving country – reveals significant differences within ethnic groups in terms of cultural norm. Finally, future research should also investigate whether, and to what extent, filial support obligations vary over time within each single ethnic group. The results reported in this article suggest that time spent in the receiving country may promote the adoption of natives’ values and norms.