Elite communication about the strengths and weaknesses of international organizations (IOs) is a common feature of global politics. National governments criticize IOs for unpopular policies, but also endorse them to protect multilateral arenas. Civil society organizations (CSOs) challenge IOs for insufficient ambitions, but also praise their efforts to consult with stakeholders. IOs themselves regularly trumpet their achievements in their public relations activities, but also occasionally admit to shortcomings. Elite communication about IOs has recently become more relevant due to challenges from populist politicians on both the right and left, who have criticized IOs for being undemocratic, politically biased and detrimental to national sovereignty.

Yet despite the prominence of elite communication in global politics, we know little about its effects on the popular legitimacy of IOs – that is, the extent to which citizens perceive an IO's authority to be appropriately exercised (Hurd Reference Hurd2007; Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte Reference Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018; Zürn Reference Zürn2018).Footnote 1 A growing literature explores the legitimation and delegitimation of IOs by national and international elites (Binder and Heupel Reference Binder and Heupel2015; Dingwerth et al. Reference Dingwerth2019; Morse and Keohane Reference Morse and Keohane2014; Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019; Zaum Reference Zaum2013). However, this literature primarily maps and explains patterns in the contestation around IOs, without assessing its consequences. With the exception of select studies on the European Union (EU) (de Vries and Edwards Reference De Vries and Edwards2009; Gabel and Scheve Reference Gabel and Scheve2007; Maier, Adam and Maier Reference Maier, Adam and Maier2012), prior studies offer few insights into the effects of elite communication on how citizens perceive the legitimacy of IOs, partly due to the methodological challenge of isolating the effects of elite communication.

It is important to establish whether (and when) elite communication affects the popular legitimacy of IOs, since this legitimacy appears to be central to IOs at consecutive stages of the policy process for four reasons (Sommerer and Agné Reference Sommerer, Agné, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018). First, popular legitimacy can affect whether IOs remain relevant as focal arenas for states' efforts to solve problems (Morse and Keohane Reference Morse and Keohane2014). As illustrated by Britain's vote to leave the EU, weak popular legitimacy can have dramatic consequences for a country's engagement with an IO.

Secondly, legitimacy in society can make it easier for IOs to gain state support for ambitious policies (Putnam Reference Putnam1988). Poor legitimacy among domestic constituencies poses a well-known constraint, for instance, on the negotiation of new trade rules within the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Thirdly, popular legitimacy can influence IOs' ability to secure compliance with international rules (Dai Reference Dai2005). For instance, weak legitimacy of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has often hampered domestic implementation of its macroeconomic prescriptions.

Finally, popular legitimacy speaks to fundamental normative concerns. If populations bound by the authority of an IO lack faith in its legitimacy, this contributes to a democratic deficit in global governance (Buchanan and Keohane Reference Buchanan and Keohane2006).

In this article, we offer the first comparative study of elite communication effects on the popular legitimacy of IOs. Drawing on cueing theory (Bullock Reference Bullock2011; Druckman and Lupia Reference Druckman and Lupia2000; Zaller Reference Zaller1992), we assume that citizens rarely have well-developed political attitudes and are therefore susceptible to elite messages. This basic logic should be particularly applicable in the global setting, since citizens generally have less information about global than domestic political institutions. We develop novel theoretical hypotheses about three particular conditions in global governance that should matter for the effects of elite communication: the communicating elites (national governments, CSOs or IOs themselves), the objects of communication (IOs' procedures or performances) and the valence of messages (positive or negative).

We test our hypotheses using data from a population-based survey experiment designed to isolate the causal effects of elite communication on legitimacy perceptions. We adopt an experimental design to bypass inference problems usually associated with cross-sectional and time-series designs. Using vignette treatments, we randomly vary the three factors of interest (elite, object and valence), which enables us to examine the causal effects on legitimacy perceptions, all else equal. While earlier research has only studied elite communication in the context of a single IO (the EU), we compare its effects across five prominent regional or global IOs: the EU, IMF, North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), United Nations (UN) and WTO. To increase external validity, we conducted the experiment among nationally representative samples of almost 10,000 respondents in three countries: Germany, the UK and the US.

Our findings demonstrate that elite communication matters for legitimacy perceptions, and show how conditions specific to the communicative setting of global governance shape effects. The central results are fourfold. First, we find that communication by national governments and CSOs has stronger effects on legitimacy perceptions than communication by IOs themselves. This suggests that IOs' increasingly prominent practice of self-legitimation confronts credibility constraints that reduce its effectiveness. Secondly, the evidence shows that elite communication affects legitimacy perceptions irrespective of whether it invokes IOs' procedures or performance. While scholars have long debated the relative importance of procedure vs. performance in assessments of legitimacy, citizens appear equally sensitive to both. Thirdly, we find that negative messages about IOs have stronger effects on legitimacy perceptions than positive messages. This suggests that the opponents of global governance face an easier task than its defenders in shaping public perceptions. Fourthly, comparing across IOs indicates that elite communication is more often effective in relation to the IMF, NAFTA and the WTO, than the EU and UN. This finding highlights the benefits of a comparative perspective, and suggests that earlier findings about the effects of elite communication on EU legitimacy, if considered in isolation and as representative of opinions about other IOs, may lead to an underestimation of the general capacity of elite communication to shape perceptions of IO legitimacy.

The state of the art

Two empirical literatures have addressed the topic of elite communication and attitudes toward IOs. Yet neither has offered a systematic and comparative account of the causal effects of elite communication on legitimacy perceptions.

In recent years there has been an upsurge of interest in political elites’ legitimation and delegitimation of IOs (Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019). This development in research reflects trends in world politics: IOs have increasingly become objects of contestation and politicization (Zürn Reference Zürn2018). The literature is centered on three themes. First, growing out of social movement research, a range of contributions have explored CSOs’ opposition to IOs (for example, Kalm and Uhlin Reference Kalm and Uhlin2015; O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien2000). Secondly, a number of studies have examined states' attempts to legitimize and delegitimize IOs in order to further their objectives in world politics (for example, Binder and Heupel Reference Binder and Heupel2015; Hurd Reference Hurd2007). Thirdly, scholars have begun to address IOs' discursive and institutional strategies of self-legitimation (for example, Zaum Reference Zaum2013; Zürn Reference Zürn2018). Taken as a whole, this growing literature maps and explains elite communication about IOs, but does not explore the conditions under which legitimation and delegitimation are successful at shaping popular perceptions of IOs.

The other relevant body of research focuses on public opinion toward IOs (Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2015; Edwards Reference Edwards2009; Johnson Reference Johnson2011; Schlipphak Reference Schlipphak2015; Voeten Reference Voeten2013). This literature is plagued by the poor availability of systematic and comparable data. The data tend to be either fragmented across disparate regional samples (for example, Eurobarometer, Afrobarometer) or insufficiently systematic in their coverage of countries and IOs (for example, World Values Survey, WVS). As a consequence, most studies focus on individual IOs; comparisons across organizations are rare. Substantively, this scholarship mainly examines how individual- and national-level factors combine to explain public support for IOs. In addition, recent experimental studies assess how institutional qualities of IOs affect public opinion toward these organizations (Anderson, Bernauer and Kachi Reference Anderson, Bernauer and Kachi2019; Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg2019). In contrast, the role of elites in shaping public opinion toward IOs has received limited attention. The exception is the sub-literature on public support for the EU, where a range of important contributions have assessed the effects of political parties' positions, polarization and communication on public support for the EU (for example, de Vries and Edwards Reference De Vries and Edwards2009; Gabel and Scheve Reference Gabel and Scheve2007; Maier, Adam and Maier Reference Maier, Adam and Maier2012). However, this literature confronts a number of restrictions. Methodologically, it has proven difficult to establish the causal effects of elite communication on attitude formation, given problems of endogeneity and omitted variables, leading to calls for experimental designs (Gabel and Scheve Reference Gabel and Scheve2007). Empirically, the scope of this literature is limited to the EU; the broader applicability of its findings has not been assessed. Theoretically, this literature is focused on how party cues influence public opinion, whereas elite communication in global governance is a broader phenomenon, involving legitimation and delegitimation by multiple types of elites.

The argument

We build on cueing theory to advance an argument about why elite communication should affect citizens' legitimacy beliefs in relation to IOs, and when those effects should be particularly strong or weak. Our argument rests on the theoretical assumption that citizens rarely have stable, consistent and informed political attitudes, and therefore may be susceptible to elite communication. This expectation unites theories of framing, persuasion and cue taking in American and Comparative Politics. It has given rise to a rich empirical literature, which explores the conditions under which public attitudes are more or less malleable (for overviews, see Busby, Flynn and Druckman Reference Busby, Flynn, Druckman and D'Angelo2018; Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a; Druckman and Lupia Reference Druckman and Lupia2000). For instance, it has been shown that people's attitudes tend to be more malleable on issues subject to less polarization (Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013).

While it is well known that elite communication matters domestically, it may have even greater effects on citizen attitudes in the international setting. Even if citizens have usually heard of the most prominent IOs (Gallup International Association 2005), they rarely have much knowledge about their political mandates, decision-making procedures or policy impacts (Dellmuth Reference Dellmuth2016). IOs are less frequently covered in national media than domestic institutions, and the transnational public sphere is less developed than its domestic counterparts. Citizens therefore rarely have access to rich and varied information about IOs, leaving attitudes more exposed to influence.

Cueing theory focuses on how elite messages shape people's opinions on an issue (Bullock Reference Bullock2011; Druckman and Lupia Reference Druckman and Lupia2000; Zaller Reference Zaller1992). A cue is a message that people may use to infer other information and thereby make decisions (Bullock Reference Bullock2011, 497). Cues thus help citizens overcome informational shortfalls about politics by simplifying choices for them (Zaller Reference Zaller1992). An issue of debate has been whether cueing primarily works through the identity of the messenger or the informational content of the message (for an overview, see Bullock Reference Bullock2011). Recent research suggests that both elite identity and informational content matter (Bullock Reference Bullock2011; Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013).

A rich literature in American and Comparative Politics draws on cueing theory to study when and how cues from political parties influence voter opinions (Broockman and Butler Reference Broockman and Butler2017; Bullock Reference Bullock2011; Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). Party cues are seen to offer explicit information about the policies and candidates supported or opposed by a party, which helps citizens form political preferences. Similarly, in International Relations, cueing theory has inspired an emerging literature that explores when and how endorsements or criticisms from various types of elites affect public opinion on foreign policy matters (Guisinger and Saunders Reference Guisinger and Saunders2017).

Drawing on cueing theory, we assume that communication by trusted elites may offer citizens cognitive shortcuts to opinions about IOs, and that citizens may be responsive to such information because it allows them to form opinions about IOs in efficient ways. Moving beyond applications of these theories to domestic politics, we theorize the specific conditions in global governance that may shape the effects of elite communication. Our argument recognizes that the contextual circumstances of elite communication vary across levels of government. While political candidates and parties are the principal communicators in domestic politics, global governance involves a different set of state and non-state elites, which raises novel questions about the effects of communication under alternative conditions. Specifically, we theorize that the strength of the communication effects will depend on the type of elite that is engaging in communication about IOs, the features of IOs invoked in the communication and the valence of the communication.

Communicating Elites

With regard to the elites engaging in communication, one of the hallmarks of global governance is the multitude of actors that aspire to influence its outcomes. Three types of elites are particularly prominent communicators about IOs: national governments, CSOs and the IOs themselves. National governments often criticize IOs in order to force policy change, deflect blame or mobilize domestic supporters, but may also endorse them to rally support for ambitious goals, lock in policy preferences and protect multilateral arenas (Morse and Keohane Reference Morse and Keohane2014). CSOs frequently challenge IOs for insufficiently ambitious policies and undemocratic decision-making procedures, but may also praise them for their policy achievements and efforts to consult with stakeholders (O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien2000). Finally, IOs themselves increasingly engage in self-legitimation, trumpeting their democratic credentials, expertise-based policies and critical achievements, but also occasionally admit to mistakes when seeking to minimize political damage or generate support for reorientation (Zaum Reference Zaum2013).

There are reasons to expect that these elites exhibit varying degrees of credibility when communicating about IOs, which has implications for the effects of this communication on citizens' legitimacy perceptions. Credibility refers to the belief that a speaker has relevant knowledge and can be trusted to reveal that information accurately (Lupia Reference Lupia and Kuklinski2000). Prior research suggests that sources which are perceived to be more credible are more successful at shaping attitudes (Druckman Reference Druckman2001). According to this view, citizens are not mindless followers of elites who might want to manipulate them, but instead listen specifically to the elites they perceive to be credible on a particular issue. In the domestic context, partisanship has been found to constitute an important source of elite credibility: citizens are more likely to follow cues from party elites whose partisan orientation they share, especially in polarized political systems (Bullock Reference Bullock2011; Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). In the global context, where elites are less strongly linked to specific partisan positions, and the issues are often less polarizing, we expect credibility to instead be tied to perceptions of impartiality. However, we also conduct robustness checks to test for moderating effects of partisan identification and trust in the domestic government on treatment effects.

This expectation of a link between credibility and impartiality is inspired by research on the impact of expert endorsements, which shows that experts can affect public opinion by virtue of their perceived unbiased knowledge (Guisinger and Saunders Reference Guisinger and Saunders2017; Maliniak et al. Reference Maliniak2019), as well as research on media priming, which shows that news sources perceived as authoritative are more likely to produce framing effects (Druckman Reference Druckman2001; Miller and Krosnick Reference Miller and Krosnick2000). Analogously, we expect that citizens consider whether elites in global governance can be expected to hold and reveal accurate information about IOs. Elites who have greater incentives to convey biased information about IOs are less likely to be seen as credible sources. Conversely, elites who stand to gain less from how IOs are perceived can be expected to communicate more honestly about these organizations.

Based on these considerations, we expect citizens to believe CSOs are more credible than national governments or IOs in their assessments of IOs for three reasons. First, CSOs are constitutively independent from IOs and are therefore more likely to be regarded as autonomous voices (cf. Gourevitch, Lake and Stein Reference Gourevitch, Lake and Stein2012). Many CSOs, such as Human Rights Watch and Transparency International, have made it their organizational purpose to offer independent assessments of norm conformance and goal achievement among IOs and their member states (Kelley and Simmons Reference Kelley and Simmons2015).

Secondly, national governments are the principals of IOs (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Lake, Nielson and Tierney2006). They have played a part in creating IOs, serve on their governing bodies and are primarily responsible for implementing their policies. As a result, governments often have particular views about how co-operation should develop, such as in conflicts over burden sharing in the EU, voting weight in the IMF and dispute settlement in the WTO. Because of these stakes, national governments are likely perceived as less credible communicators than CSOs.

Thirdly, IOs have the most far-reaching vested interests in debates about themselves. Their bureaucracies are committed to advancing the goals of these organizations, but depend on the support of their political environment to achieve them (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004). We therefore expect IOs to be the least credible source of information about themselves. We find support for this gradation of credibility in data on popular confidence in different elites worldwide. Data from the most recent wave of the WVS (2010–2014) suggest that environmental and women's CSOs are more credible than both governments and IOs, and that governments are more credible than IOs such as the UN and NAFTA (see Appendix C). This leads to a first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (Elites) The more credible elites are perceived to be by citizens, the stronger their impact on citizens' perceptions of IO legitimacy, all else equal.

Objects of Communication

We assume that elite communication about IOs typically attempts to affect individual attitudes by invoking two alternative grounds for endorsement or criticism: the procedures and performance of IOs. An extensive literature shows that favorable attitudes toward a political institution may be shaped by the procedures and performance of that institution – both in the context of domestic politics (Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2012; Newton and Norris Reference Newton, Norris, Pharr and Putnam2000) and global governance (Bernauer and Gampfer Reference Bernauer and Gampfer2013; Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2015). Thus elites interested in shaping citizens’ attitudes toward IOs frequently refer to these features. Procedural standards invoked in elite communication often relate to democratic aspects of IO policy making, such as inclusiveness and accountability, but can also pertain to expertise and efficiency (Binder and Heupel Reference Binder and Heupel2015). Performance standards include aspects of goal achievement, such as problem-solving effectiveness and collective welfare gains, but can also relate to the fairness of outcomes (Zürn Reference Zürn2018).

Whether citizens' legitimacy perceptions are most sensitive to the procedures or performance of IOs is a topic of debate. Procedural accounts submit that process criteria are the most important for people's perceptions of legitimacy. Even when institutions generate outcomes that are to their disadvantage, actors accept their exercise of authority because of how they were set up and operate (Hurd Reference Hurd2007, 71). Procedural accounts have an antecedent in Weber's (Reference Weber1978[1922]) notion of rational–legal legitimacy, which emphasizes properly administered rules by properly appointed authorities. The idea that legitimacy results from features of the decision-making process is prominent in contemporary theories of procedural fairness (Tyler Reference Tyler1990) and democratic legitimacy (Held and Koenig-Archibugi Reference Held and Koenig-Archibugi2005).

Performance accounts instead claim that legitimacy perceptions are determined by institutions' contributions to collective welfare and distributional outcomes. Substantive outcomes are considered more powerful in shaping the perceptions of institutions than the process by which those outcomes were produced (Hurd Reference Hurd2007, 67). This idea features prominently in the study of domestic institutions: ‘Government institutions that perform well are likely to elicit the confidence of citizens; those that perform badly or ineffectively generate feelings of distrust and low confidence’ (Newton and Norris Reference Newton, Norris, Pharr and Putnam2000, 61). In the global setting, it is commonly claimed that IOs historically have earned their legitimacy through the benefits they have produced for states and societies (Buchanan and Keohane Reference Buchanan and Keohane2006).

Cueing theory gives us no reason to expect that the effectiveness of elite communication would vary depending on the features of IOs that are invoked. If it is correct that citizens consider both the procedures and performance of IOs when forming legitimacy perceptions (Anderson, Bernauer and Kachi Reference Anderson, Bernauer and Kachi2019; Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg2019), then elite communication that invokes these features should be effective in both cases. This leads us to expect:

Hypothesis 2 (Object) Elite communication affects citizens' perceptions of IO legitimacy irrespective of whether it refers to the procedures or performance of IOs, all else equal.

Valence

Finally, we consider how the tone of elite communication may influence the strength of cueing effects. As previously described, elite communication spans the full evaluative spectrum, from endorsing, praising and defending IOs to challenging, criticizing and dismissing them. All types of elites perform these positive and negative discursive strategies, which are frequently referred to as the legitimation and delegitimation of IOs, respectively (Binder and Heupel Reference Binder and Heupel2015; Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte Reference Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018; Zaum Reference Zaum2013; Zürn Reference Zürn2018). Empirical examples include US President Donald Trump calling NAFTA the worst trade deal the US ever signed (New York Times, 30 March 2017), Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis accusing the EU of terrorism during the country's economic crisis (BBC, 4 July 2015), and UN Secretary-General António Guterres praising the organization's peacekeepers for making the world safer (UN, 30 May 2017).

The study and practice of legitimation and delegitimation assume that the evaluative component of communication matters. It is by praising or criticizing IOs that elite messages become potentially powerful in shaping citizen attitudes. Few would expect neutral elite messages to be influential. This expectation is borne out in studies showing that positive and negative elite cues shape public support for the EU (Maier, Adam and Maier Reference Maier, Adam and Maier2012) and on international issues generally (Guisinger and Saunders Reference Guisinger and Saunders2017). However, it is an unexplored question whether legitimation or delegitimation is systematically more or less effective at shaping citizen attitudes toward IOs.

We expect negative elite messages to have stronger effects on legitimacy perceptions than positive messages. We base this expectation on theories in comparative politics, economics and psychology. While identifying slightly different mechanisms, all ground their expectations in general socio-psychological dynamics, and all suggest that negative messages should have a larger impact.

Research on voting behavior shows that people respond asymmetrically to positive and negative information about the economy (Bloom and Price Reference Bloom and Price1975; Soroka Reference Soroka2006). Since people tend to be slightly optimistic in their basic predisposition, negative information usually diverges more from their reference points than positive information, and therefore has a greater impact on attitudes and behavior. This dynamic has also been identified in communication about political candidates and institutions (for example, Lau Reference Lau1985).

Prospect theory suggests a similar story of asymmetry, highlighting a complementary mechanism. It submits that individuals tend to be risk averse, and weigh potential losses more heavily than potential gains (Kahneman and Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979; Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981). Such loss aversion leads people to react more strongly to negative information than to positive, for instance, by cutting back consumption more sharply in response to bad news than they expand consumption in response to good news.

Finally, psychological research on impression formation establishes that bad emotions weigh more heavily than good emotions. Negative information tends to be processed more thoroughly, be stickier and have a greater impact than positive information. As Baumeister et al. (Reference Baumeister2001, 323) summarize: ‘The greater power of bad events over good ones is found in everyday events, major life events, close relationship outcomes, social network patterns, interpersonal interactions, and learning processes…Bad is stronger than good, as a general principle across a broad range of psychological phenomena’.

We expect these general socio-psychological dynamics to also influence how people respond to communication about IOs. They suggest a third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (Valence) Delegitimation attempts have a stronger impact than legitimation attempts on citizens' perceptions of IO legitimacy, all else equal.

Research design

To examine our hypotheses, we conducted a survey experiment (Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Schlipphak2019). This method has advantages in identifying communication effects compared to alternative methods (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a). Cross-sectional or time-series analyses of observational survey data often confront problems of endogeneity and omitted variables. While instrumental variables present a solution that may reduce bias from endogeneity, identifying suitable instrumental variables is often challenging (Gabel and Scheve Reference Gabel and Scheve2007). In experiments, the randomization of individuals to treatment groups and a control group addresses potential biases from endogeneity and omitted variables by ensuring that the observed treatment differences do not systematically depend on potentially uncontrolled influences. When experiments are conducted among representative samples of a population, they combine the high internal validity of experiments with the ability to generalize findings within a given population (Mutz Reference Mutz2011).

Survey Design

We conducted our survey experiment among nationally representative samples in three countries – Germany, the UK and the US – in order to reduce the risk of biases from contextual country factors. Averaging the communication effects across populations from different countries strengthens the external validity of our findings. We selected these countries since they: (a) are politically central in the examined IOs, which makes our findings substantively important for the prospects of global governance; (b) are democratic, which avoids the issue that the legitimacy of political institutions may mean different things to citizens of democratic and autocratic regimes (Jamal and Nooruddin Reference Jamal and Nooruddin2010) and (c) have very high levels of Internet penetration (over 80 per cent), which increases our confidence in the external validity of the data.

To implement the questionnaire, we relied on online panels from YouGov, a well-reputed global survey company (Berinsky, Huber and Lenz Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012). YouGov uses targeted quota sampling with the aim of achieving representative samples at the end of the fieldwork. The samples for our survey were matched to the full populations of the three countries using age, education, gender and party identification. To enable researchers to take national differences in sampling procedures into account, YouGov creates a variable denoting the optimal weight that should be assigned to each observation in order to achieve nationally representative results (for a detailed discussion, see Ansolabehere and Schaffner Reference Ansolabehere and Schaffner2014). While the sample should thus be generalizable to the populations of these countries, the YouGov online panel is self-recruited, which may introduce motivational factors. Participants receive small monetary incentives for their participation, such as entries into prize draws. Since our goal is to establish causal effects through an experiment with high internal validity, rather than to identify absolute levels of perceived legitimacy in a population, we consider this risk acceptable. A total of 3,270 interviews were conducted in the UK, 3,268 in Germany, and 3,135 in the US in January 2015. In addition to the experiment, the survey (Appendix A) included several attitudinal and demographic questions, which we use to describe the country-specific samples (Appendix Table B1), and for balance tests (see below).

Experimental Conditions

To isolate the causal effects of elite communication, we randomly assigned individuals to groups that received different experimental treatments, and a control group that did not receive any treatment. We used a vignette approach to treatment, which is well suited for complex factorial experiments (Mutz Reference Mutz2011, 54). Vignettes are short statements that contain the treatment and precede the question of interest. The purpose of vignette treatments is to assess what difference it makes when the factors embedded in the vignette are systematically varied. In this case, we manipulated three features of the communicative situation: the elite making the statement (Hypothesis 1), the object of communication (Hypothesis 2) and the valence of the message (Hypothesis 3). The vignettes were formulated in a way that allowed us to vary the three factors with precision, but also to express the subject matter in concrete terms so that it would be understandable to respondents (Gibson Reference Gibson2008). Moreover, we sought to formulate vignettes that would work equally well for all IOs and that were short and straightforward, since longer and more complex vignettes make it more difficult to determine what individuals respond to (Mutz Reference Mutz2011, 64–65).Footnote 2

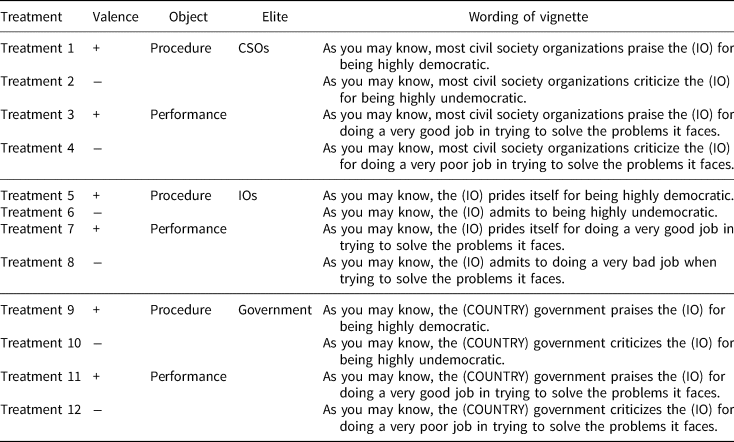

The treatments combined into a 3 × 2 × 2 factorial design, with a total of twelve conditions (Table 1). We allocated the same number of individuals to each combination of factors, and the number of respondents who provided a substantive answer was eventually relatively even across groups (see Appendix Table B2).

Table 1. Vignettes

To examine Hypothesis 1, we varied the elite making the statement in the vignette: CSOs, national governments or IOs themselves. To assess Hypothesis 2, we formulated vignettes about the procedures and performance of IOs: procedural vignettes invoked IOs’ democratic character and performance vignettes the problem-solving effectiveness of IOs.Footnote 3 To evaluate Hypothesis 3, we designed the vignettes so that they included positive or negative statements about IOs.

We operationalize legitimacy perceptions by using a question about confidence in IOs: ‘How much confidence do you personally have in the [IO] on a scale from 0 (no confidence) to 10 (complete confidence)?’ While legitimacy perceptions are a complex phenomenon, confidence has three main advantages as an indicator. First, it aligns well with our conceptualization of legitimacy as the belief that an institution exercises its authority appropriately. The confidence measure taps into respondents' general faith in an institution, independent of short-term satisfaction with specific policy decisions and outcomes (Easton Reference Easton1975; Norris Reference Norris2011). Secondly, a narrow measure of legitimacy beliefs, such as confidence (or trust), has advantages when studying the sources or effects of legitimacy. Different from some alternative operationalizations (for example, Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2012), confidence does not integrate into the measure either potential institutional sources of legitimacy (such as the perceived fairness or effectiveness of an institution) or potential consequences of legitimacy (such as compliance with an institution's rules). While some studies use a multi-item measure to capture various complexities of legitimacy as a concept, these studies usually invoke a broader conceptualization of legitimacy, incorporating normative standards to be met by an institution and/or acceptance of the rules of an institution (for example, Anderson, Bernauer and Kachi Reference Anderson, Bernauer and Kachi2019; Gilley Reference Gilley2006). Thirdly, the confidence measure allows us to relate the findings of this study to the large literature on public opinion that also employs confidence (or trust) as an indicator of legitimacy perceptions (for example, Bühlmann and Kunz Reference Bühlmann and Kunz2011; Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2015; Dellmuth and Schlipphak Reference Johnson2019; Johnson Reference Johnson2011; Norris Reference Norris2011; Voeten Reference Voeten2013).

In the experiment, the control group only received the question about confidence in a particular IO. The treatment groups (Table 1) received a specific vignette first and then the confidence question. Respondents were never allocated to the same treatment group twice. Respondents who were placed in the control group remained in this group throughout all four rounds.

Experimental Rounds

Moving beyond the strict hypothesis test, we also explored the extent to which communication effects vary across IOs. We therefore conducted the survey experiment in several rounds; each round performed the same experiment on a different IO. We selected five IOs that are central in their respective policy domains and prominent in public debate: three at the global level (IMF, UN and WTO) and two at the regional level (EU and NAFTA). While some IOs fly beneath the radar of public awareness, we selected organizations that are both known to citizens at a basic level and regularly subject to positive and negative communication by elites.Footnote 4 This ensures that treatments expressing elite messages about these IOs are understandable and reasonable to respondents. At the same time, the levels of citizen familiarity and public debate differ across these IOs, suggesting potential explanations of variation in the treatment effects, which are further explored in the comparative analysis. Respondents were asked about the regional IO of which their country is a member. That is, the question about confidence in NAFTA was only asked in the US, and the question about confidence in the EU only in the UK and Germany. The order of the experimental rounds for all respondents was: UN, EU/NAFTA, IMF and WTO.Footnote 5

Results

We discuss the results for each hypothesis in turn, and then disaggregate the analysis by IO.Footnote 6

Communicating Elites

The first hypothesis predicts that elite type matters for the effectiveness of elite communication, and yields two observable implications. First, the differences in mean confidence between the treatment groups for the different elite types and the control group should be statistically significant. Secondly, the differences in mean confidence between the treatment groups for the different elites should be statistically significant. In line with our theory, we expect CSOs to be most effective, national governments less effective and IOs themselves least effective in communication about IOs. To explore these observable implications, we pooled the data across the four experimental rounds so that the observations on confidence in the different IOs are clustered at the individual level. We then collapsed the treatment groups on procedure and performance to allow us to contrast the effects of negative communication by CSOs, IOs and governments as well as positive communication by the same elites.Footnote 7 To this end, we created several dummy variables indicating whether respondents were exposed to a specific vignette.

We find evidence that the effects on confidence in IOs depend on the type of elite, which largely corroborates Hypothesis 1 (Figure 1). In line with the first observable implication, the first six treatment effects indicate that communication by all three elite types affects citizens' confidence in IOs. These effects are potentially substantively important when considering that they result from a one-off exposure to treatment. For example, the first treatment effect (0.356) indicates that citizens who have received positively framed messages from CSOs on average have 0.356 more confidence in IOs on an 11-point scale, compared to those who did not receive such messages. However, the third treatment effect is not statistically significant, suggesting that IOs cannot successfully legitimize themselves in the eyes of citizens through appeals to their procedures or performance.

Figure 1. Communicating elites

Note: average treatment effects with their respective 95% confidence intervals, based on weighted data. See Appendix D for detailed results.

Most importantly, the second observable implication receives support as well, albeit not in all parts. The last six treatment effects in Figure 1 indicate that there are some differences in the strength of communication effects between the three types of elites. The results suggest that CSOs manage to sway confidence in IOs more than the IOs themselves, irrespective of whether they seek to legitimize or delegitimize IOs. Similarly, governments appear to shape legitimacy perceptions more than IOs when seeking to enhance confidence in IOs, but not when attempting to weaken it. However, the evidence also suggests that CSOs are not more effective than governments in shaping citizens' confidence in IOs, contrary to our expectation.

These results suggest that the credibility of elites affects their capacity to sway public perceptions of IOs. IOs appear unable to increase their own legitimacy by presenting themselves in a positive fashion. They are likely perceived as partial, and therefore non-credible, as a source of positive information about their own merits. The finding in other research that IO endorsements can affect public opinion about state foreign policy is not at odds with this result, as IOs in those cases communicate about other actors (Chapman Reference Chapman2009). While IOs increasingly engage in various forms of self-legitimation, our findings question the effectiveness of that strategy. Instead, they suggest that IOs have to rely on positive communication by CSOs and national governments to increase their legitimacy. The finding that these two latter types of elites are equally effective communicators may be due to citizens not perceiving governments as partial principals of IOs, but as credible voices about the merits of these organizations.

Object of Communication

The second hypothesis predicts that elite communication is equally effective when invoking the performance and procedures of IOs as grounds for endorsement or criticism. Hypothesis 2 has three observable implications. First, the differences in mean confidence between the procedure group and the control group, as well as between the performance group and the control group, should be statistically significant. Secondly, the differences in mean confidence in these group comparisons should be similar in size. Thirdly, there should not be a statistically significant difference in mean confidence between the procedure and performance groups. To test this hypothesis, we collapsed the treatment groups for the different elites and created a series of dummy variables indicating if respondents received positive or negative procedural or performance treatments.

In line with the first observable implication, the differences in means between the four treatment groups and the control group, respectively, are statistically significant (Figure 2). This indicates that positive and negative messages about both the procedures and performance of IOs are effective at swaying citizen confidence. Consistent with the second observable implication, the differences in mean confidence in these group comparisons are also very similar in size, suggesting that procedure and performance have equally strong effects. This finding is ultimately confirmed by the last two treatment effects in Figure 2, which show statistically insignificant results for the difference-in-means test between procedural and performance treatments, in keeping with the third observable implication. This is corroborated by a t-test statistic for independent samples (t = 0.002 when comparing positive procedural and performance treatments and t = 0.013 when comparing negative procedural and performance treatments).Footnote 8

Figure 2. Object of communication

Note: average treatment effects with their respective 95% confidence intervals, based on weighted data. See Appendix D for detailed results.

These results suggest that citizens care equally about IOs' procedures and performance when developing legitimacy perceptions (see also Anderson, Bernauer and Kachi Reference Anderson, Bernauer and Kachi2019; Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg2019). Theoretical accounts that privilege one or the other appear misguided. Contrary to claims that democratic procedure has become the foremost source of legitimacy (Held and Koenig-Archibugi Reference Held and Koenig-Archibugi2005), citizens may value IO performance just as much. Conversely, it would appear imprudent to conclude from findings in recent scholarship that citizens mainly care about IOs' capacity to deliver (Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2015), irrespective of the procedures they use to develop policies. From the perspective of communicating elites, there may be a wide menu of messages for effective legitimation or delegitimation of IOs.

Valence

The third hypothesis predicts that the valence of messages matters for the effectiveness of elite communication. Hypothesis 3 has two observable implications. First, the differences in means between the group receiving negative treatments and the control group, as well as between the group receiving positive treatments and the control group, should be statistically significant. Secondly, the difference in means between the negative and positive treatment groups should be statistically significant, and negative messages should have stronger effects than positive.

Figure 3 shows that the results are in line with both observable implications. Both positive and negative treatments affect legitimacy perceptions. By implication, the difference in means of −0.517 on the 0–10 confidence scale between negative and positive treatment groups is also statistically significant. Furthermore, negative communication (−0.277) has stronger effects than positive (0.240). The statistically significant difference between negative and positive treatments is corroborated by a t-test statistic for independent samples (t = 5.113, see footnote 8).

Figure 3. Valence

Note: average treatment effects with their respective 95% confidence intervals, based on weighted data. See Appendix D for detailed results.

Figures 1 and 2 further show that this pattern largely holds even when we disaggregate by the elites making the statements and the objects of communication. Figure 2 shows that the effects of negative messages are larger than those of positive messages, regardless of whether elites refer to procedure or performance. The findings in Figure 1 show a more varied pattern. In line with the expectation, they indicate that elite communication by IOs is more effective when negatively expressed. However, for CSOs and governments, the effects are larger when the communication is positively expressed. When we disaggregate by IOs, we find that the statistically significant difference in effects between positive and negative messages holds for all five IOs (Figures 4–6).

Figure 4. Subgroup analysis: communicating elites

Note: average treatment effects with their respective 95% confidence intervals, based on weighted data. Sample size is about 3,000 for the global organizations, about 2,000 for the EU and about 800 for NAFTA. See Appendix E for detailed results.

Figure 5. Subgroup analysis: object of communication

Note: average treatment effects with their respective 95% confidence intervals, based on weighted data. Sample size is about 3,000 for the global organizations, about 2,000 for the EU and about 800 for NAFTA. See Appendix E for detailed results.

Figure 6. Subgroup analysis: valence

Note: average treatment effects with their respective 95% confidence intervals, based on weighted data. Sample size is about 3,000 for the global organizations, about 2,000 for the EU and about 800 for NAFTA. See Appendix E for detailed results.

Overall, these results suggest that delegitimation of IOs by their opponents is more successful than legitimation by IOs themselves and their supporters. In line with earlier socio-psychological findings, people appear to be more sensitive to negative information than to positive. Our findings suggest a problematic relationship in the public contestation over IOs. While public criticism of IOs is often intended to push these organizations to improve, rather than undermine them, such advocacy efforts are likely to have costly negative externalities in terms of reduced public confidence.

Disaggregating treatment effects across IOs

Finally, we complement the hypothesis tests with an exploratory analysis of the extent to which communication effects vary across IOs. This analysis allows us to assess if cueing effects occur less often in the context of the EU compared to other IOs, since most of what we know about the effects of elite communication comes from studies of this organization. If cueing is more often effective in relation to other IOs compared to the EU, this suggests that findings in the European setting may have underestimated the importance of elite communication.

As a starting point, we consider the possibility that communication effects vary with the familiarity of IOs, based on the premise that citizens should be more susceptible to cueing on issues that are less familiar to them (Zaller Reference Zaller1992). The best available survey data suggest that the UN and EU are better known to citizens in the included countries than the IMF and WTO (see footnote 4).

For this analysis, we re-examine the differences in means between the treatment groups and the control group presented in Figures 1–3, but now at the level of individual IOs (see Figures 4–6, based on results detailed in Appendix E). The confidence intervals indicate a 95 per cent certainty that the true treatment effect lies within their range. If the confidence intervals include zero, the treatment effect is not statistically significant.

The analysis shows that the occurrence of treatment effects varies across IOs in ways that are often – but not always – consistent with the expectation that familiarity matters. We exclusively report variation in the occurrence of effects, since differences in the strength of effects across IOs are not statistically significant, as indicated by the overlapping confidence intervals.

We begin by assessing the occurrence of treatment effects by IO for different elite types (Figure 4). Positive communication by CSOs is effective in relation to the UN, IMF and WTO, while negative communication only is effective in relation to the UN and NAFTA. Positive communication by IOs never appears to work, mirroring the general ineffectiveness of IO self-legitimation, while negative communication works in all cases but NAFTA. Positive communication by governments about the UN and WTO seems to influence legitimacy perceptions, while negative communication works in the case of the WTO and EU. In sum, elite communication tends to lead to treatment effects in relation to the UN, WTO and IMF, while we see fewer significant effects for the EU and NAFTA.

Figure 5 reveals a similar pattern across IOs when comparing communication about their procedures and performance. We observe statistically significant effects for all or most treatments relating to the UN, WTO and IMF. Conversely, only one treatment pertaining to the EU yields a statistically significant effect and no treatment at all in the case of NAFTA. We observe the same pattern with regard to valance. As Figure 6 shows, positive communication works in the UN, IMF and WTO, but not in the EU and NAFTA, while negative communication appears to work in the context of all IOs except NAFTA.

Taken together, these results indicate that elite communication is more often effective in the context of some IOs than in others. The pattern is partly consistent with the baseline expectation that citizen familiarity with IOs matters for the effectiveness of elite communication: cueing more often produces significant effects in the context of the IMF and WTO, and more seldom in the context of the EU. However, two IOs diverge from the expected pattern: the UN and NAFTA. We suspect that these exceptions reflect variation in the public contestation of IOs. Earlier research established that elite communication tends to be less effective when issues are more polarized and people have developed stronger priors (Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). While NAFTA is slightly less familiar than the UN, it likely has been subject to greater political contestation in the US in recent years (Hurrelmann and Schneider Reference Hurrelmann and Schneider2015), leading citizens to adopt more developed and less malleable attitudes toward the organization. The same factor might also contribute to the limited effectiveness of elite communication in relation to the EU, as European integration is highly contested in some member countries.

Robustness Checks

We perform seven robustness checks. First, we replicate all analyses presented in Figures 1–6, including country dummies to check whether some of the results are driven by potentially unobserved country-specific variables. This change in model specification does not alter the interpretation of our results (see Appendix F).Footnote 9

Secondly, we go one step further and replicate all analyses at the level of individual countries (Appendix G). The main results from the pooled analysis are robust across countries with a few notable exceptions. In Germany, the varying effectiveness of negative and positive treatments is compounded by positive communication not swaying citizen confidence in IOs at all. The expected results for communicating elites, objects of communication and valence remain robust (Tables G1–G3). In the UK, the results hold across the board, except that negative communication by CSOs is not effective and the government does not appear to be more effective at swaying public opinion than IOs themselves (Tables G5–G7). The latter finding may be due to the extreme dissatisfaction with the British government at the time of our survey. According to the British Social Attitudes survey, only 17 per cent of the population had confidence in the government in 2015.Footnote 10 The main results also hold in the US, even if fewer treatments are significant (Tables G9–G11). The main deviation is that the government appears to be a more effective communicator than both CSOs and IOs themselves (Tables G9). This may reflect greater skepticism about the impartiality of CSOs in the US than elsewhere (Gourevitch, Lake and Stein Reference Gourevitch, Lake and Stein2012). When we disaggregate the country analyses by IO, the pattern is somewhat more heterogeneous, likely reflecting a combination of country-specific experiences of IOs and less statistical power (Tables G4, G8 and G12).

Thirdly, we examined whether eight different individual characteristics measured in the survey, including education and age, are evenly distributed across the conditions we aggregated for the analysis. The results increase our confidence in the randomization of the subjects among treatment groups. We only discover imbalances in six of the ninety-six tests. Balance tests using the twelve treatment conditions in Table 1 show four imbalances for ninety-six tests (see Table 1 and Appendix Tables H1–H2).

Fourthly, we examine whether there are potentially undesired spillover effects because the order of the four experimental rounds was not randomized. For this purpose, we conducted balance tests for each round separately to assess if the fixed order of the rounds could have given rise to biases resulting from dropouts (Appendix Tables H3–H10). We found no pattern indicating a potential systematic bias, as approximately the same (very low) number of balance tests is statistically significant in each round. Still, we examine potential biases further, as the absence of randomization of experimental rounds may give rise to varying distributions of respondents across samples. Indeed, the number of respondents providing substantive answers drops when comparing rounds 1 and 4 (Appendix Table B2). We test whether the experimental effects vary across the four rounds by plotting the predicted marginal effects of the various treatments for different rounds (Appendix I). The slopes of the dummy variables for the specific treatments are largely parallel across the four experimental rounds, indicating an absence of systematic differences.

Fifthly, we replicated all analyses in order to check whether item non-response may have affected the results. If the use of the ‘don't know’ option reflects, for instance, less political knowledge about IOs, these values would not be missing at random (Rubin Reference Rubin1976, 582) and average treatment effects may be biased. We therefore examined the causal process behind missingness, and found that item non-response is unlikely to have affected our results (see Appendix J). While the effects of socio-demographic factors become smaller when comparing rounds 1 and 4, possibly because the samples have become more homogenous due to increasing item non-response, we also find instances of effect sizes becoming larger when comparing across other rounds (for example, education across rounds 3 and 4, and age and gender across rounds 1 and 2). Taken together, the evidence from the balance tests, plots of experimental effects across the four rounds, and item non-response analysis corroborates our confidence in our interpretation of experimental effects across rounds in light of our theoretical argument.

Sixthly, we examine whether the results for governments as communicating elites are conditional on whether people identify with a political party in government and whether people trust their own government. We find that, while the effect of the positive government treatment is unconditional on these two factors, the effect of the negative government treatment is moderated by partisan identification and confidence in national government (Appendix K). More specifically, the negative effect of the negative government treatment is only statistically significant among those who identify with a party in government (Appendix Figure K1) and becomes stronger the higher the respondent's trust in government (Appendix Figure K2). These findings are in line with previous research suggesting that people who distrust their own government are unlikely to follow government cues (Aaroe Reference Aaroe2012), and that a political party's cues work best among those who identify with that party (Maier, Adam and Maier Reference Maier, Adam and Maier2012).

Finally, we examine whether treatment effects might be conditional on political awareness. A large public opinion literature suggests that politically aware individuals are more likely to comprehend and integrate new information into their opinion formation (Druckman and Nelson Reference Druckman and Nelson2003). Yet they also tend to hold more consistent and stable opinions, and may therefore be less responsive to experimental treatments (cf. Zaller Reference Zaller1992). We test these issues by interacting the treatment dummies with two awareness indicators (Appendix Tables K3–K8). The results suggest that more knowledgeable citizens did not respond differently than less knowledgeable citizens when confronted with our vignettes.

Conclusion

Whether citizens perceive IOs as legitimate matters for effectiveness and democracy in global governance. IOs whose legitimacy is challenged may find it more difficult to stay relevant as political arenas, gain support for ambitious new policies, secure compliance with international rules and meet normative criteria of democratic governance (Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte Reference Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018). Against this backdrop, we have evaluated the conditions under which elite communication affects the popular legitimacy of IOs.

The results indicate that: (a) more credible elites – CSOs and governments – tend to affect legitimacy perceptions more than less credible elites – IOs themselves; (b) legitimacy perceptions are equally affected by messages about the procedures and performance of IOs; and (c) delegitimation attempts have stronger effects on legitimacy perceptions than legitimation attempts. Moreover, a comparative analysis suggests that communication effects are more often effective in the context of the UN, IMF and WTO, than in the EU or NAFTA, which can potentially be explained by variation in the familiarity and contestation of IOs. These findings highlight the value of a comparative design for isolating variation and avoiding biased conclusions. They suggest that any inference from previous studies focused on the EU to IOs more generally may underestimate the effects of elite communication at the international level.

We see at least three promising extensions of this research agenda. First, single experiments are seldom sufficient to prove a theory. The empirical test of our argument involved a number of choices that could have affected its findings. Future research could assess the broader robustness of our results using, for instance, alternative operationalizations of legitimacy perceptions and other treatment formulations. Secondly, future studies may explore the generalizability of our findings. It is conceivable that the effects of elite communication are systematically stronger or weaker for a different set of elites (Maliniak et al. Reference Maliniak2019), for IOs engaged in other issue areas (Guisinger and Saunders Reference Guisinger and Saunders2017) or for another group of countries. Thirdly, our analysis invites efforts to assess the effects of elite communication under alternative conditions. It appears particularly relevant to explore how effects on legitimacy beliefs toward IOs are affected by varying levels of ideological division among elites (Gabel and Scheve Reference Gabel and Scheve2007), varying degrees of conflict across messages (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007b), varying time horizons (Druckman et al. Reference Druckman2010) and varying characteristics among citizens beyond those explored here (Zaller Reference Zaller1992).

Beyond these extensions, our findings suggest three broader implications for research and policy. First, they speak to research on the sources of legitimacy in global governance. They show that citizen attitudes toward IOs are not determined exclusively by individual (Armingeon and Ceka Reference Armingeon and Ceka2014), institutional (Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg2019) and country factors (Edwards Reference Edwards2009); they are also shaped by elites' communication about these organizations. Legitimacy perceptions are not set, but continuously evolving, as citizens integrate arguments and information from trusted elites. These findings complement the growing literature on legitimation and delegitimation in global governance (Binder and Heupel Reference Binder and Heupel2015; Dingwerth et al. Reference Dingwerth2019; Zaum Reference Zaum2013; Zürn Reference Zürn2018) by showing how such communicative practices impact legitimacy beliefs.

Secondly, our results shed light on the applicability of cueing theory to politics at the global level, where elite communication operates under different conditions. This article is the first to show how communication effects are shaped by the specific circumstances of global governance, highlighting the varying impact of different global elites across a multitude of IOs. With the growing internationalization of politics, it becomes increasingly important for public opinion research to explore how political communication and attitude formation work in the global realm. Future research should exploit the complexity of global governance to theorize and assess how cueing might work differently under these conditions, for instance, regarding the influence of political parties and the role of elite polarization. International issues are typically assumed to be less politically divisive among elites and less politically salient to citizens than domestic issues (Aldrich et al. Reference Aldrich2006). This may be one reason why we found elite credibility based on impartiality, rather than partisanship, to matter in the global setting, which is contrary to conventional expectations (Bullock Reference Bullock2011; Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013).

Thirdly, in the area of practical politics, the results suggest an uphill battle for elites concerned with the legitimacy of global and, especially, regional IOs. While IOs invest considerable resources in public communication (Ecker-Ehrhardt Reference Ecker-Ehrhardt2018; Zaum Reference Zaum2013), citizens are often not convinced by IOs' attempts to talk up their legitimacy. This indicates that IOs' best chance of boosting their legitimacy is to mobilize supporters among civil society and national political elites who can speak on their behalf. For these advocates of multilateral cooperation, it is good news that citizens are equally responsive to communication about the democratic qualities and problem-solving effectiveness of IOs, since this expands the range of legitimation narratives that may be effectively used. Yet such efforts face the challenge that positive communication is less effective than negative communication in shaping citizen attitudes. Messages that criticize global governance more easily get through to citizens than those that speak to its virtues. In the political struggle over the popular legitimacy of IOs, the elites of discontent appear to hold the upper hand.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UM6KP5 and online appendices at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000620.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions in Warsaw in 2015, the Annual Convention of the ISA in Atlanta in 2016, and research seminars and workshops at Stanford University, Stockholm University, University of Oslo, University of Oxford and WZB Social Science Center Berlin. For helpful comments and suggestions, we are particularly grateful to Brilé Anderson, Thomas Bernauer, Henning Best, Klaus Dingwerth, Erica Gould, Aya Kachi, Judith Kelley, Bob Keohane, Dan Maliniak, Dan Nielson, Christian Rauh, Duncan Snidal, Mike Tierney, Mike Tomz, Kåre Vernby, Michael Zürn, as well as two reviewers and the editor Tobias Böhmelt for BJPolS. The research for this article was funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (M15-0048:1) and the Swedish Research Council (2015-00948).