INTRODUCTION

In June 1960, four undergraduate students from the Geology Department at The Pennsylvania State University drove west to attend a month-long geology field school offered by the University of Wyoming. The students—Steve Kirsch, Harry McGoldrick, Jeffrey Parsons, and Paul Visocky—were fulfilling a requirement for their Bachelor of Science degrees in geology. Upon completing training in geological field mapping, Jeff Parsons remained in the west for the rest of the summer, joining Pennsylvania State University geology professor Robert Scholten as a field assistant mapping geological formations along the Continental Divide in southwestern Montana and adjacent central and northern Idaho. Jeff had never been out of the eastern US before, apart from a brief trip to Canada. The trip west was a grand adventure, involving experiences, places, and lifestyles he had never seen before—project headquarters in a tent that moved from place to place, working in mountainous settings previously unknown, food cooked on an open fire while discussing the day's fieldwork, and sharing stories. It also introduced him to key new skills, including the use of aerial photographs as base maps to guide fieldwork and to map geological features. For all four students, the summer of 1960 was an important experience in their young lives, both academically and personally. For Jeff, a bright, good-natured, understated young man, that summer introduced him to vital new skills, a love of fieldwork, and an interest in visiting and understanding new places that would remain with him the rest of his life. He used those skills and interests to change the discipline of archaeology.

Jeffrey Robinson Parsons died on March 19, 2021, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with his wife Mary by his side, as she had been for more than half a century. He passed after a brief illness. To many of us who knew of his struggles with health the preceding month, it still came as quite a shock. Over the ensuing days and weeks following his passing, a flood of messages arrived from colleagues, former students, and various acquaintances that testified to the number of lives Jeff had touched in significant ways. Many of these messages spoke of his contributions to archaeology, his value as a colleague, and his willingness to help others, particularly students and young professionals, further their careers. One would expect such comments at the passing of a senior scholar and teacher who had accomplished so much. But most of these messages also reflected on Jeff's spirit and kindness, his good humor and easygoing nature, and, as one former student put it, his fundamental decency. In a world increasingly dominated by harsh personalities and a drive to succeed above all else, Jeff Parsons was remembered as much for his kindness, generosity, and congeniality as for his considerable professional accomplishments.

Writing obituaries is not a task anyone really looks forward to doing. As we prepared the following pages, we individually searched for personal experiences over many decades and from different perspectives, first as students and then as colleagues of Jeff, but also as friends. Beyond the personal reflections, however, there is the burden of responsibility to do justice to one of the great scholars in our field. Jeff was a gentle soul who quietly made enormous contributions not only to the study of ancient Mesoamerica and the Andes, but to the entire discipline of archaeology. In addition, he documented aspects of traditional rural lifeways rooted in the past and rapidly disappearing. He did all of this by assembling a variety of skills and interests and working hard, but in the process never losing touch with his humanity. In the end, this has been a cathartic exercise, as it gave us a chance to reflect on the contributions made by Jeffrey R. Parsons to archaeology and anthropology and, more important, on the many ways he touched the lives of others.

EARLY YEARS: GROWING UP AND GEOLOGY AT THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY

Jeff Parsons was born in Washington, DC, on October 9, 1939, the oldest child of Merton Stanley Parsons (1907–1982) and Elisabeth Oldenburg Parsons (1911–2005). His parents both had graduate degrees from Cornell University, where they met in 1935, and shared similar backgrounds, having grown up on farms, his father in western Maine and his mother in central New York (Parsons Reference Parsons2009b:3). At the time of Jeff's birth, the Parsons family lived in Maryland, near Washington, DC, relocating in 1941 to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and then, in 1946, to Fairfax, Virginia. Currently part of the DC urban sprawl, Fairfax was semirural when Jeff lived there. He and his younger sister and brother were involved in 4-H activities, and the family had a large garden and raised bees and chickens while Jeff's father worked as an agricultural economist for the United States Department of Agriculture (Parsons Reference Parsons2009b:3). Jeff described himself as a “middle-class white boy” with two “well-educated and supportive parents,” noting that his childhood was in no way remarkable (Parsons Reference Parsons2019a:3). Summers involved spending time with friends and exploring the outdoors, including bicycling along small country roads that today are filled with six or eight lanes of traffic. The family spent parts of the summer on the family farm in Maine, giving Jeff both an appreciation and respect for people involved in farming, often under challenging conditions. In Fairfax, Jeff often accompanied his father on long walks, and he and his friends explored nearby fields searching for arrowheads and bullets from Civil War battles. And he read, being raised in a house full of books by a mother who loved reading; one book he read as a youth was Life in Ancient Egypt and Assyria (Maspero Reference Maspero1892), his first exposure to archaeological literature. Jeff would later reflect on the role that these earlier experiences had on his decision to pursue archaeology as a career (Figure 1; Parsons Reference Parsons2009b:3–4, Reference Parsons2019a:13).

Figure 1. Jeffrey Robinson Parsons, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 16 months, 1941. Photographer unknown.

As part of his job, Jeff's father occasionally visited agricultural programs at various universities. In 1955, Jeff accompanied him on a visit to Pennsylvania State University, leading Jeff to apply there the following year (Nichols Reference Nichols and Brereton2006:107). He chose to attend Penn State and began his freshman year in September 1957. In those years, the university required students to declare a major when they started classes; based on results of an aptitude test, Jeff chose geology. He would reflect later that he never felt pressured to choose one field or another; although it was assumed that he and his siblings would attend university, they could pursue the field of their choosing (Parsons Reference Parsons2019a:4). He majored in geology and minerology, graduating as the top student in the College of Mineral Industries, an accomplishment that Jeff characteristically never mentioned (though it is documented in a letter from Penn State to Jeff's father; Parsons Reference Parsons2019a:5). But as time went on, Jeff grew less interested in his major and felt a need to expand his educational horizons. He laid the groundwork for such expansion in his first geology field experience in June 1960.

Geology and Minerology majors at Penn State were required to enroll in a field school after completing their junior year. Jeff attended the University of Wyoming field school in the summer of 1960 to learn geological field mapping because it fit this schedule. But his participation as geology professor Rob Scholten's field assistant in Montana and Idaho following field school was something extra and an important addition to his experience. Professor Scholten and student Parsons explored extremely remote localities along the Continental Divide in those two states. They lived in a tent, drank water from streams, ventured well off even the most remote roads and trails, and cooked over an open fire. They used the skills that Jeff had learned in field school and others that Scholten knew to locate and record geological formations using aerial photographs. They saw local people pursuing livelihoods previously unfamiliar to a student raised in the eastern US, such as open-range sheepherding. And they talked, with Scholten describing his own life as a young man growing up in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands during World War II, including his work with the resistance and his time in a labor camp after narrowly escaping execution at the hands of the Gestapo. For the rising university senior from Fairfax, Virginia, this was adventure well beyond expectation, and looking back one wonders if the greatest impact on Jeff's career came from gaining new technical skills or from the excitement of exposure to new places and new lifeways while working with an extremely skilled and interesting professor. Indeed, the adventure continued as Jeff visited the west coast and then returned to Virginia and Penn State after the field season, by Greyhound bus and hitchhiking, further broadening his horizons.

When Jeff returned to Penn State, he decided to fulfill some elective requirements for his degree by enrolling in courses that addressed topics other than geology. He selected a course in Mesoamerican archaeology taught by then Assistant Professor William T. Sanders. Sanders let Jeff enroll despite his lack of prerequisites if Jeff agreed to take another anthropology course concurrently (Nichols Reference Nichols and Brereton2006:108). Admitting Jeff into his course turned out to be an extremely consequential decision both for Jeff and for Bill Sanders. Sanders’ passion for Mesoamerican archaeology inspired Jeff, causing him to recall the Maspero book he had read as a child as well as experiences searching for Civil War artifacts and arrowheads near his home in Virginia. Motivated by Sanders, Jeff decided late that term to make a dramatic change and pursue graduate studies in anthropology with an archaeological focus. With advice from Penn State graduate students and faculty, including Sanders, and University of Michigan alumnus Professor Fred Matson, Jeff applied to two programs—the University of Arizona and the University of Michigan. Despite lacking anthropology courses on his transcript, both programs accepted Jeff. James B. Griffin, legendary long-term Director of the Museum of Anthropology at Michigan, successfully lured Jeff with a research assistantship. For its part, the College of Mineral Industries at Penn State was perplexed: how could the only student in the college graduating with “highest distinction” be leaving a discipline with such career potential to pursue archaeology? The Acting Dean of the College wrote to Jeff's father expressing his dismay and suggesting that, with some experience in archaeology, Jeff might see the error in his ways and return to the fold (Parsons Reference Parsons2019a:5).

In addition to deciding to pursue graduate training in anthropology, in fall 1960 Jeff also applied to be a student assistant the following summer on Sanders’ field project in the Teotihuacan Valley. That project was representative of an emerging emphasis of archaeology in the 1960s on studying the past from an anthropological and social science perspective to understand fundamental processes associated with sociocultural evolution (Nichols Reference Nichols, Mastache, Parsons, Puche and Santley1996; Sabloff and Ashmore Reference Sabloff, Ashmore, Feinman and Price2001). The Teotihuacan Valley Project combined archaeological excavation with settlement pattern survey, an emerging approach that sought to locate all sites in a region, building on ideas introduced by Sanders’ Ph.D. advisor Gordon Willey in his study of the Virú Valley of Peru a few years earlier (Willey Reference Willey1953). Sanders saw Jeff's role as the project geologist (Nichols Reference Nichols and Brereton2006:110), but Jeff lacked the depth of experience examining geomorphology and landform formation processes necessary to provide the essential geological insights, something he would express as a regret later in his career (Parsons Reference Parsons2009b:12). During the preceding summer, however, Jeff had learned how to use aerial photographs to map features systematically, skills that would pay enormous dividends in the Teotihuacan Valley and beyond.

As we sifted through various resources and our own memories, and discussed Jeff's early history with his wife, Mary, and other friends, it seems that the seeds for what he would contribute to archaeology and for the person he would become had been firmly planted early in life. Certainly, the geology background and the technical knowledge of using aerial photographs and other mapping technologies were instrumental to Jeff's contributions to settlement pattern mapping. Growing up in a supportive household where reading and curiosity were encouraged also were fundamental, with Jeff's geology field experience tapping into the latter. But here was a young man raised in a rural-suburban setting who knew of and appreciated farming, having come from generations of people who extracted a living from the land and having spent some time on the Maine family farm. And, finally, here was a student with a passion for fieldwork—something that not everyone shares—a characteristic that he would muse about later in life while recounting the missed opportunity to fit in “just one more survey” to fill a data gap in the northern Basin of Mexico. On reflection, Jeff Parsons was well poised for the next stage of his life.

COMING OF AGE IN THE TEOTIHUACAN VALLEY… AND A FIRST GLIMPSE AT REGIONAL ARCHAEOLOGY

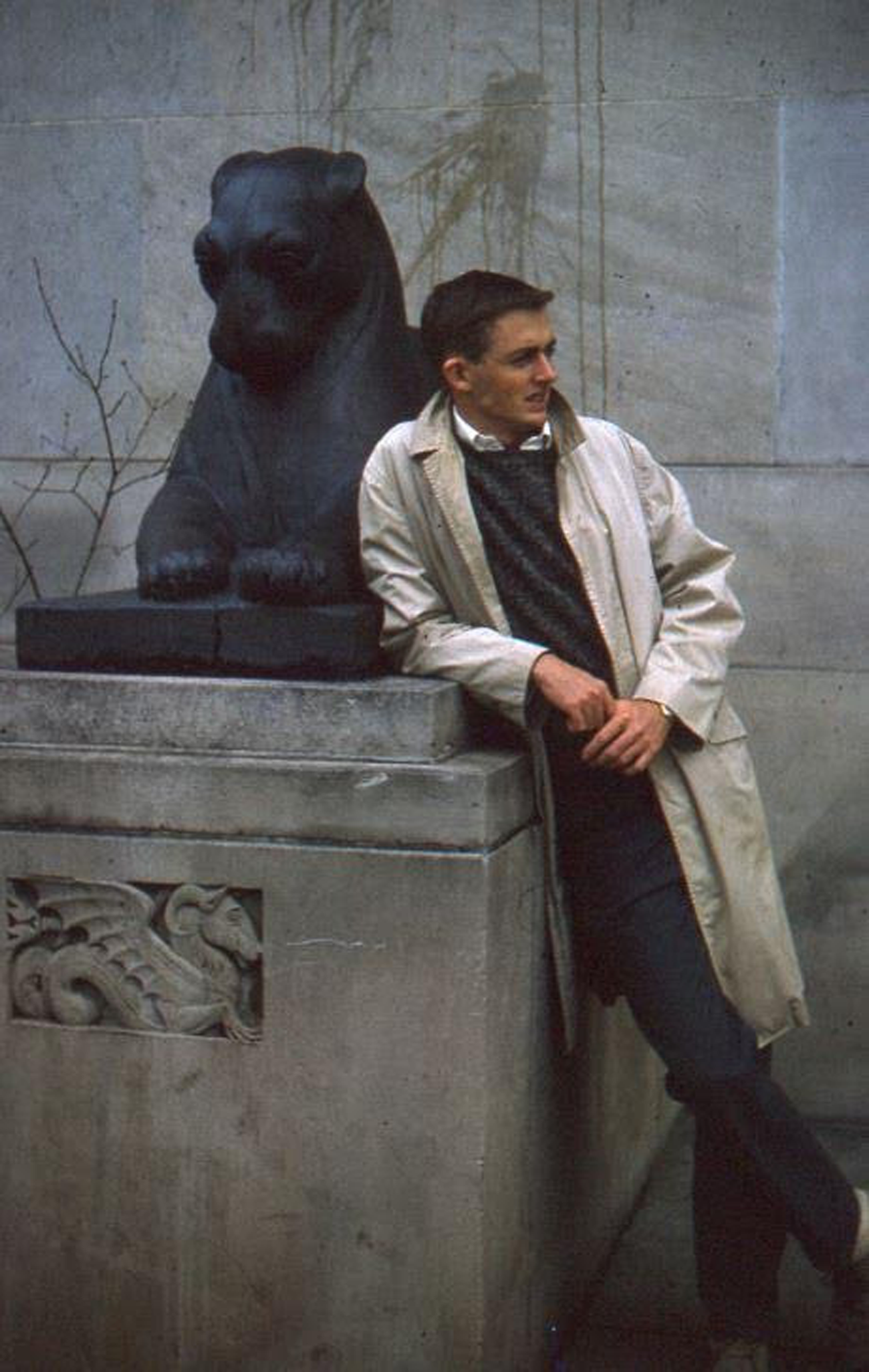

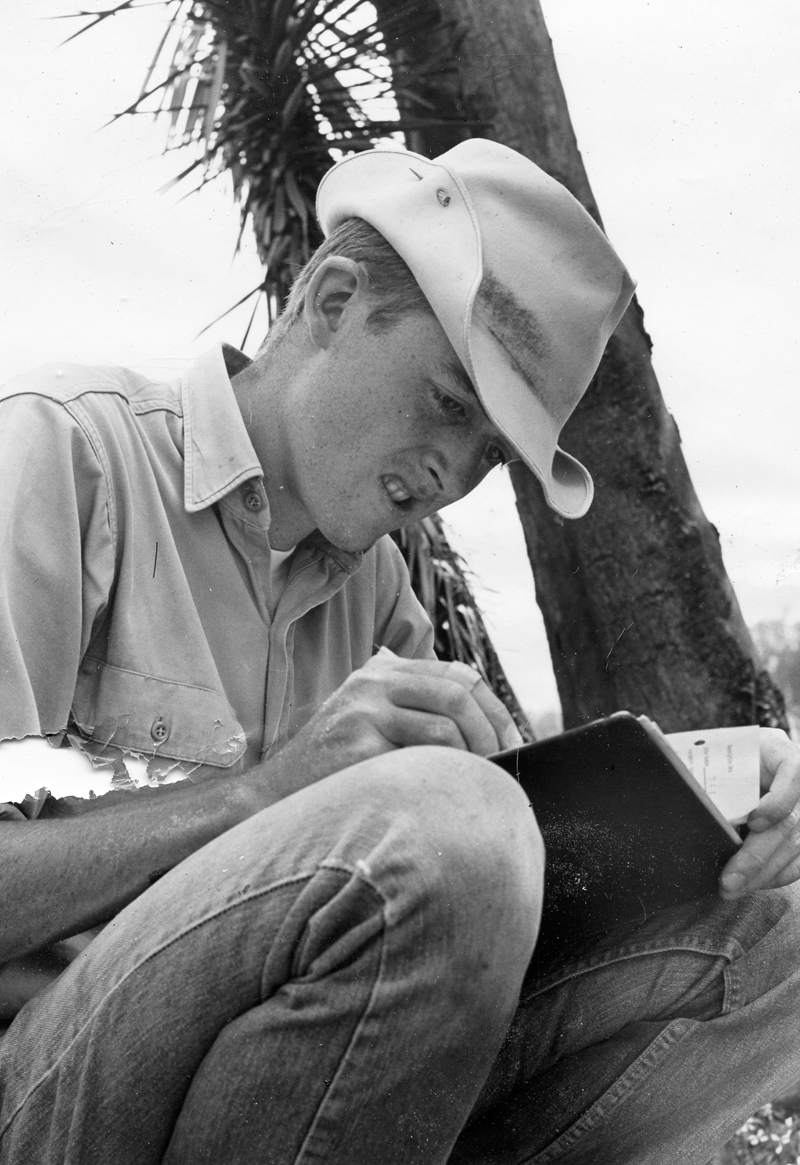

Jeff joined Bill Sanders and his field crew in the Teotihuacan Valley in June 1961 (Figure 2) and became a graduate student in anthropology at the University of Michigan in fall of that same year (Figure 3). Jeff would work in the Teotihuacan Valley for four consecutive field seasons and, following a brief hiatus in 1965 to finish his doctoral dissertation, for a fifth season in 1966. He wrote of these years, and spoke of them often, with fond nostalgia (Parsons Reference Parsons2009b, Reference Parsons2019a, Reference Parsons2022). He was living away from home for an extended period in a foreign country. He was surrounded by sights and tastes and smells and experiences that all seemed exotic to this young man from suburban Washington. He was working on an exciting project led by a charismatic young professor and involving other students with whom he would become lifelong friends. He was developing friendships with residents of Teotihuacan who knew him as “Joaquin,” relationships that yielded additional insights into life in rural Mexico in the early 1960s. Although Jeff would never stop growing intellectually, these early years in the Teotihuacan Valley clearly laid the foundation for the archaeologist he would become. Indeed, he captured some of this experience in his own words (Parsons Reference Parsons2009b:5): “How I loved Mexico in my youth! It was so exotic and so appealing to me: the archaeology was fantastic; the traditional lifeways were interesting; the scenery was terrific; the beer was great; the girls were pretty; the people were friendly; and what few dollars I had went a long way.”

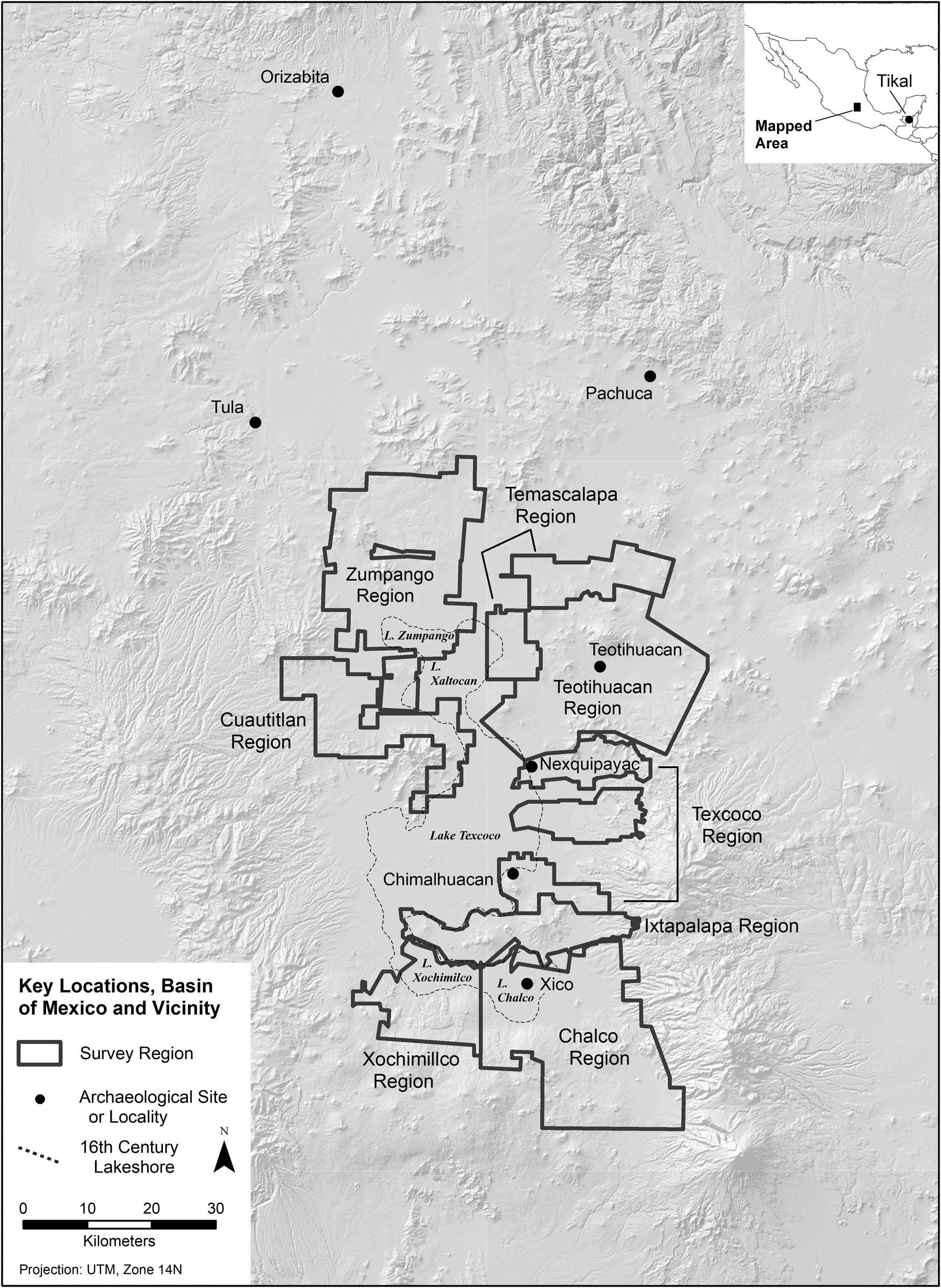

Figure 2. Survey regions and other locations in Mexico mentioned in the text. Map by Gorenflo.

Figure 3. Jeff Parsons in front of the University of Michigan Museums Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1962. Photographer unknown.

The Teotihuacan Valley Project was innovative in many ways. Jeff observed that this was good as his lack of prior archaeological fieldwork was not a major hinderance in a project exploring approaches new to most archaeologists (Parsons Reference Parsons2022:15). Moreover, Jeff's experience in the western US the previous summer provided him with a valuable skillset—reading aerial photographs and using them to record surface features. The shift of focus from geological features to archaeological remains was an easy one: it provided Jeff with the opportunity to make a key contribution to the Teotihuacan Valley Project and, it turns out, to projects in the future through greatly refining the then-emerging methodology of archaeological survey and advancing regional archaeology.

Jeff's first two years of the Teotihuacan Valley Project—1961 and 1962—were spent excavating and surveying. In the early years of that project, survey occurred in two phases: a general survey to locate archaeological sites and develop a rough sense of their age and contents; and a more focused survey, led by a crew member who had developed expertise in a particular period of occupation, to understand sites more thoroughly. In the first year, Jeff worked on excavations directed by other crew members with more experience and used an alidade and plane table (other holdovers of his geology training the preceding summer) to map excavations. In the second year, Jeff directed the excavation of the Mixcuyo Site, an arrangement of several hundred, small, lunate terraces up the side of a hill, later found to be nineteenth-century features associated with maguey cultivation. In both years, Sanders took students on short trips to explore other noteworthy archaeological or historical localities in the Basin of Mexico. Jeff augmented these group experiences with weekend outings—hiking with crew members to other Basin of Mexico localities, exploring parts of Mexico City, and traveling by bus or train to more distant parts of Mexico. Reading excerpts of letters he wrote to his parents during those seasons, one is struck by two things: his growing fondness for Mexico in general and the Basin of Mexico in particular; and his interest in much of what he saw—people, places, land use, archaeological sites, and patterns of rural and urban behavior (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Jeff Parsons recording fieldnotes at the Mixcuyo Site in the Teotihuacan Valley, Basin of Mexico, 1962. Photograph by Bill Mather.

During his final two years on the Teotihuacan Valley Project, Jeff worked exclusively on pedestrian survey. He led the survey of Aztec sites, the most prevalent in the valley. That task took him to many parts of the valley and exposed him to a wide variety of archaeological remains, landforms, land uses, and other cultural behavior. The focus exclusively on survey seemed to have been a natural fit for Jeff, despite the constant pressure to record data on the many Aztec sites found earlier in the project (Parsons Reference Parsons2022:87–89). The work involved spending time at individual sites to make surface collections and describe each site in detail. During these seasons he began to explore improvements to the survey methods used on the project. He continued to travel around the Basin of Mexico and beyond, visiting different areas and different cultural settings. His love of Mexico had become firmly established.

The summer of 1965 involved no fieldwork. Jeff spent those months at Penn State completing an analysis of Aztec pottery in the Teotihuacan Valley for his Ph.D. dissertation. At the same time, the University of Michigan had decided to expand its archaeological focus and was seeking someone who specialized in Latin America. After unsuccessfully trying to hire Sanders, who chose to remain at Penn State where they were building their own anthropology program, and passing on two other established archaeologists, Jimmy Griffin asked Jeff if he would be interested in the job. Jeff accepted and, following the successful defense of his dissertation in January 1966, joined the faculty. Sanders would later remark that Griffin said although they had not succeeded in landing him, they hired the next best thing—a promising young scholar trained by him.

Newly minted Assistant Professor Parsons returned to the Basin of Mexico briefly with a crew of six University of Michigan graduate students in May 1966. One of those students, Mary Hrones, would catch Jeff's eye and they would marry two years later (Figure 5). Following the practice of Bill Sanders, Jeff took his crew on several field trips to other noteworthy archaeological sites—Tula, the obsidian mines near Pachuca just north of the Basin of Mexico, and remnant chinampas (high-productivity agricultural fields in wetlands) near Xochimilco in the southern basin (Parsons Reference Parsons2022:103–109). They all worked together completing the Teotihuacan Valley survey, focusing on the eastern portion of the region, with the aim to get the crew oriented on the new method that Jeff had developed and, to some extent, was still refining for surface survey in the region. Jeff's knowledge of the valley and its residents made the experience for his young crew a rich one, introducing them to the archaeology of the region as well as the culture of rural central Mexico in the mid-1960s. Recalling those days, crew member accounts of the experience are very similar to those Jeff had noted for himself—fascinating archaeology mixed with rich cultural experiences and personal growth. Jeff then left the students working in the Teotihuacan Valley for 10 weeks and joined a survey in Tikal, Guatemala, directed by University of Pennsylvania graduate student Dennis Puleston. This trip was Jeff's first archaeological foray outside of Mexico (other than some brief experience in southern Michigan), exposing him to more new cultures and very different fieldwork conditions (Parsons Reference Parsons2010a). Oriented around brechas—major axes running north, south, east, and west from the center of Tikal—the survey required that fieldworkers use machetes to cut their ways 250 m into the dense forest at predetermined starting points along the brechas and identify any archaeological features encountered. The work was hard and conditions grueling, but Jeff would have very good memories of that project and Denny Puleston for the rest of his life. Jeff's ability to adapt to varying conditions, to endure hardships in the field, and to envision archaeological survey as requiring different methods in different settings, were honed in the Tikal survey. Those lessons would serve him well in the future. He returned to the Teotihuacan Valley in early August to help the Michigan students finish surveying the valley. While in Guatemala, Jeff had decided to return to the Basin of Mexico for more fieldwork, beginning with survey of the Texcoco region in the eastern Basin of Mexico in 1967.

Figure 5. Jeff and Mary Parsons at the Greenwood Ice Caves, Maine, 1984. Photographer unknown.

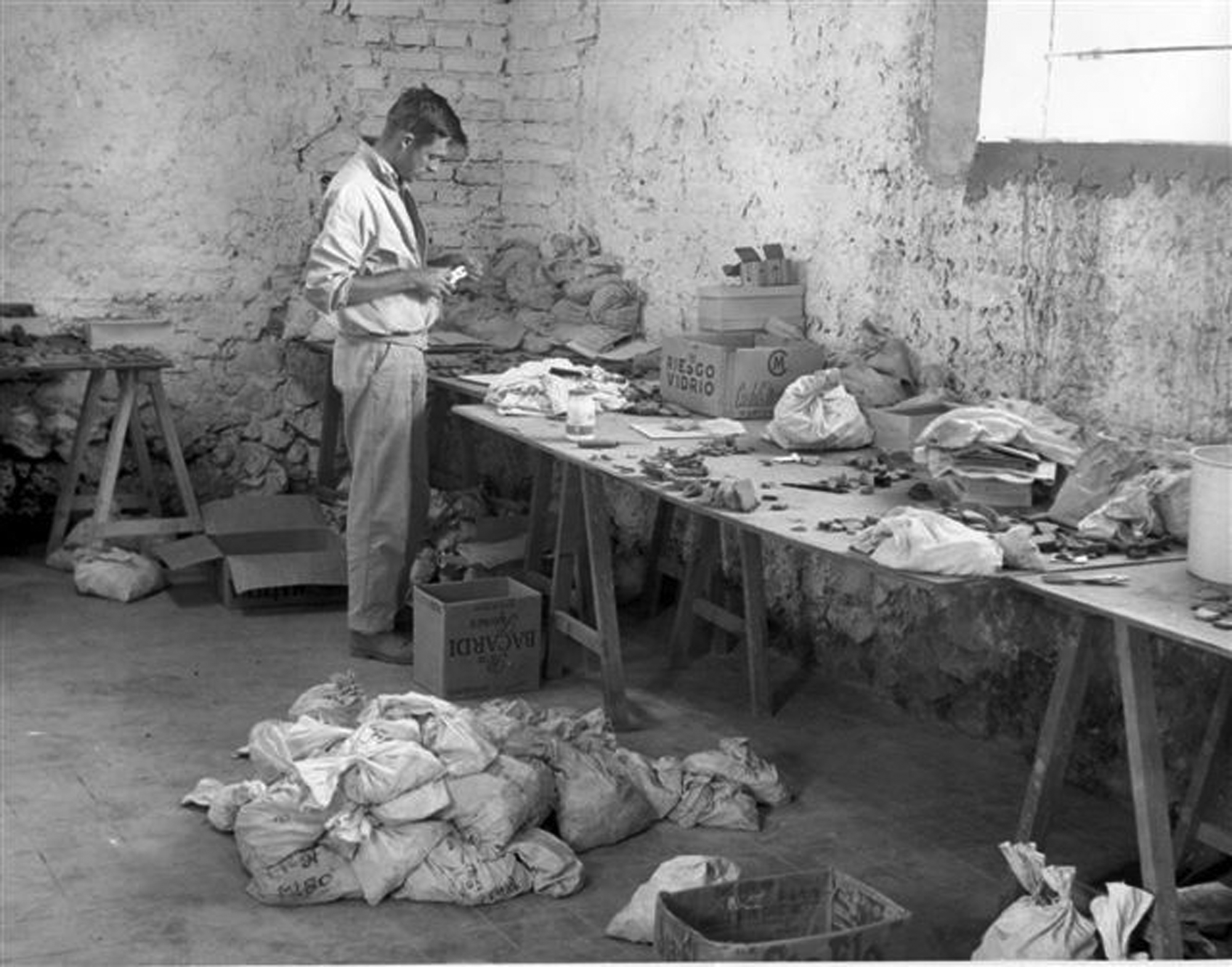

In closing this section, we wanted to remark on the source of many of our insights on Jeff's years as a young archaeologist in the early 1960s. Certainly, we based much the preceding text on many conversations over the years, along with some personal experiences. But we also drew upon letters written by Jeff to his parents and letters written by Mary to her parents. Jeff was fortunate to come from a family that carefully documented many parts of their lives—in letters, diaries, and photographs. He continued this practice and we have benefitted from it, the photographic record of his early archaeological experiences complemented by his own reflections and by letters that he retrieved and later published in part following the passing of his and Mary's parents (Figure 6; Parsons Reference Parsons2019a, Reference Parsons2022).

Figure 6. Jeff Parsons at the Teotihuacan Valley Project headquarters, Teotihuacan, Mexico, 1963. Photograph by Bill Mather.

APPLYING A REGIONAL PERSPECTIVE: THE BASIN OF MEXICO

Bill Sanders saw the Teotihuacan Valley Project as the first in a series of studies of the Basin of Mexico. But Sanders’ own success pulled him in other directions. Jeff Parsons had grown up archaeologically doing survey in the basin, had secured a good job at the University of Michigan, and was perfectly poised to step into the task of surveying more of the region. By the end of the Teotihuacan Valley Project, Jeff's focus on Aztec sites had led him to survey more of the valley than anyone else on the crew. He decided to take on the challenge of surveying much of the remainder of the basin. With funding largely from the National Science Foundation (NSF), he led surveys of the Texcoco region (1967; Parsons Reference Parsons1971; Figure 7), the Chalco-Xochimilco regions (1969 and 1972; Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Brumfiel, Parsons and Wilson1982), and the Zumpango region (1973; Parsons Reference Parsons2008b). Richard Blanton, at the time a graduate student of Jeff's at the University of Michigan, surveyed the Ixtapalapa region in 1969 (Blanton Reference Blanton1972). Sanders would finish the Basin of Mexico surveys by covering the Cuautitlan (1974; Sanders and Gorenflo Reference Sanders and Gorenflo2007) and Temascalapa (1974 and 1975) regions (Figure 2; Gorenflo and Sanders Reference Gorenflo and Sanders2022). Between 1960 and 1975, the surveys discovered more than 3,900 archaeological sites (Gorenflo Reference Gorenflo2015; Gorenflo and Sanders Reference Gorenflo and Sanders2007; Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Kintigh and Gregg1983) and produced one of the most valuable datasets in archaeology. Along with Bill Sanders and Robert Santley, Jeff would summarize these projects and their contributions to understanding pre-Columbian sociocultural evolution in the Basin of Mexico in a classic 1979 book (The Basin of Mexico: Ecological Processes in the Evolution of a Civilization), routinely called La Biblia Verde (The Green Bible; Gándara [Reference Gándara2011]) in Mexico for the color of its cover and the influence it would have on the archaeology of the basin and beyond (Sanders et al. Reference Sanders, Parsons and Santley1979).

Figure 7. Jeff Parsons at Tetzotzingo, Texcoco Survey Region, Basin of Mexico, 1967. Photographer unknown.

Jeff's role in surveying the Basin of Mexico obviously was irreplaceable, in part because he led surveys of what was the largest portion of the region. One of his greatest contributions, however, was refinement of a survey methodology that efficiently yielded reliable, detailed, regional settlement data. He built the Texcoco region survey methodology on lessons learned in the Teotihuacan Valley, trying to address what he felt were shortcomings in the earlier fieldwork. One useful change was collapsing the two-phase approach into a single survey; site location and evaluation would now occur at the same time. Another was replacing smaller aerial photographs used in the Teotihuacan Valley with large formats, the roughly 50 × 50 cm, 1:5,000 photos being more conducive to guiding fieldwork and mapping archaeological remains. Jeff combined these refinements with meticulous field notes and annotations on the aerial photographs, something that our colleague Kenneth Hirth noted recently in recalling his experience working with records from Jeff's surveys. These refinements were later adopted by Sanders in the final two survey regions.

Systematic regional survey clearly was Jeff Parsons’ forte in archaeology, well suited to his emerging interests as well as his fast, long stride. He would comment privately on how he liked to cover large areas and discover previously undocumented sites in new settings that hosted a variety of different land uses. But there were scientific reasons for his interest as well. As the surveys proceeded, Jeff began to get a sense of how the pre-Columbian Basin of Mexico worked. One sees hints of this insight in a 1968 publication in Science, immediately following the Texcoco survey, in which he begins to explore how urban Teotihuacan fit demographically into a larger regional context (Parsons Reference Parsons1968). He had begun to experience the benefits of a regional perspective personally, and in talking to him hints of these insights often preceded final analyses and publication. Jeff had become so familiar with the data, the anthropological problems associated with the evolution of pre-Columbian sociocultural systems in the Basin of Mexico, and the region itself, that he began to see patterns emerge in the field—relatively late initial settlement in the Zumpango region in the northwestern basin (Parsons Reference Parsons2008b; see also Parsons and Gorenflo Reference Parsons and Gorenflo2022a, Reference Parsons, Gorenflo, Córdova and Morehart2022b); interrupted settlement in the Texcoco region in the Early Postclassic period (a.d. 950–1150) that seemed to mark an administrative boundary between the northwestern and southeastern basin (Sanders et al. Reference Sanders, Parsons and Santley1979:140–149); potential groupings of settlements into local polities; and so on.

A particularly valuable characteristic of the Basin of Mexico surveys was their timing. Simply put, the archaeological record was disappearing, and the various forms of development underlying site destruction would accelerate markedly during the 1960s and 1970s. The loss of archaeological sites in the basin was a recurring theme in Jeff's publications, presentations, and conversations (Parsons Reference Parsons, Fish and Kowalewski1990, Reference Parsons1991, Reference Parsons, Drennan and Mora2001b, Reference Parsons, Drennan and Mora2003, Reference Parsons2009b, Reference Parsons2015), and something that he thought about often. The time of those surveys was when the greatest historic population growth occurred in the Basin of Mexico, a problem exacerbated by the expansion of commercial agriculture and accompanying destructive land modification (Gorenflo Reference Gorenflo, Córdova and Morehart2022; Parsons Reference Parsons2019a:336–342). Jeff would later comment that had they to do it all over again, they should have started in the southwestern basin in the early 1960s and proceeded northeast towards the Teotihuacan Valley, in a sense surveying just beyond the expanding urban sprawl, rather than beginning in a more isolated rural northeastern valley.

Meticulous field notes carried into meticulous publications. As Jeff's University of Michigan colleague Henry Wright (Reference Wright2021) observed, the survey monographs that Jeff published set the standard for such offerings. Anyone who has tried to emulate that model will attest as to the magnitude of the task. The delay in publishing survey results was something that bothered Jeff (Parsons Reference Parsons2009b:13; Reference Parsons2019a:216), though the reason for delay was always additional fieldwork in Mexico and elsewhere, to get data out of the field before they were destroyed or otherwise compromised. In addition to the survey monographs, Jeff published a volume of tabular descriptions of sites, evidence of his willingness to share data with the broader archaeological community (Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Kintigh and Gregg1983).

It is easy to forget that all these survey projects in the Basin of Mexico occurred amid considerable fieldwork in coastal Peru, a period early in Jeff's career during which it seemed he was constantly in the field. Indeed, he once remarked on how little he was in Ann Arbor during his first several years as a University of Michigan faculty member. Initially hired to help create a Latin American archaeology program at the Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Jeff had looked beyond central Mexico to develop a broader foundation. But his interest in developing a basis for comparative studies came at the cost of not being able to examine either area in the depth he would have liked, something he would reflect on late in his career despite his massive contributions to the archaeology of the Basin of Mexico and the Peruvian Andes (Parsons Reference Parsons2009b:10–12).

EXPANDING HIS PERSPECTIVE: COASTAL PERU AND THE CENTRAL ANDES

To expand Jeff's Latin American field experience beyond central Mexico, Griffin secured Museum funds to support a two-month exploratory trip for Jeff to Peru and Bolivia in September 1966. Lorenzo Rosselló, a Peruvian businessman with a keen interest in archaeology, had spent 1940–1941 studying architecture at the University of Michigan and was eager to see a Michigan archaeologist conduct research in his country. He used his broad connections to introduce Jeff to the major figures in Peruvian archaeology. Jeff traveled extensively, often with Rosselló, beginning in Lima and the central coast but then moving to the north-central highlands and the north and north-central coast of Peru before visiting the southern highlands of Peru on the way to La Paz and Lake Titicaca, Bolivia. This trip, following closely on the heels of his Tikal survey experience earlier that same year, greatly expanded Jeff's personal knowledge of key areas of Latin American archaeology. His reaction to this new area was very positive. As Mexico had impressed him five years earlier, he was fascinated by the new places he saw, noting personally unfamiliar landforms that included coastal deserts and massive mountains and grasslands in high altitudes, the strong presence of Indigenous culture in the highlands, new lifeways and foods, and remarkable archaeology in the region (Parsons Reference Parsons2009b:7). The journey also increased Jeff's interest in comparing the evolution of pre-Columbian civilizations in Mesoamerica and the Andes, and he began to think about possibly returning to Peru or Bolivia to lead a field project (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Jeff Parsons in front of a chulpa wall, Silustani, Peru, 1970. Photograph by Mary Parsons.

Jeff initially hoped to return to conduct surface survey in the Moche Valley of Peru or around the urban center of Tiwanaku in Bolivia, neither of which worked out (Parsons Reference Parsons2019a:122). During his exploratory excursion, however, he had visited sunken fields (locally named mahamaes; Parsons Reference Parsons2022:244) near the community of Chilca, about 70 kilometers south of Lima, and he applied for funding to support an examination of their function and possible contribution to agricultural production in this arid region (Figure 9). The sunken fields were an interesting contrast to the chinampa agriculture Jeff had seen in the Basin of Mexico, both representing a considerable investment in labor that would have to return high yields to justify the cost of construction and maintenance. But their creation employed opposite strategies—chinampas constructed in wetlands by raising the ground surface to a point where it would enable crop production, sunken fields constructed in arid areas to lower the ground surface, possibly to increase plant access to the groundwater. Jeff secured NSF funding to study sunken fields over two field seasons. Accompanied by Mary, the first season in 1969 focused on aerial photograph research in Peru to identify occurrences of sunken fields up and down the Peruvian coast, and the second season in 1970 focused on fieldwork to examine some of the fields identified the preceding year. Test excavations provided a sense of how sunken fields were constructed and used. Those excavations, coupled with observations of sunken fields currently in use, interpretations by geomorphologists and soil scientists brought into the project, and discussions with locals, indicated different functions that sunken fields could perform with their improved access to the water table—including crop production, grazing, growing reeds, and making salt (Parsons and Psuty Reference Parsons and Psuty1974, Reference Parsons and Psuty1975).

Figure 9. Survey regions and other locations in Peru and Bolivia mentioned in text. Map by Gorenflo.

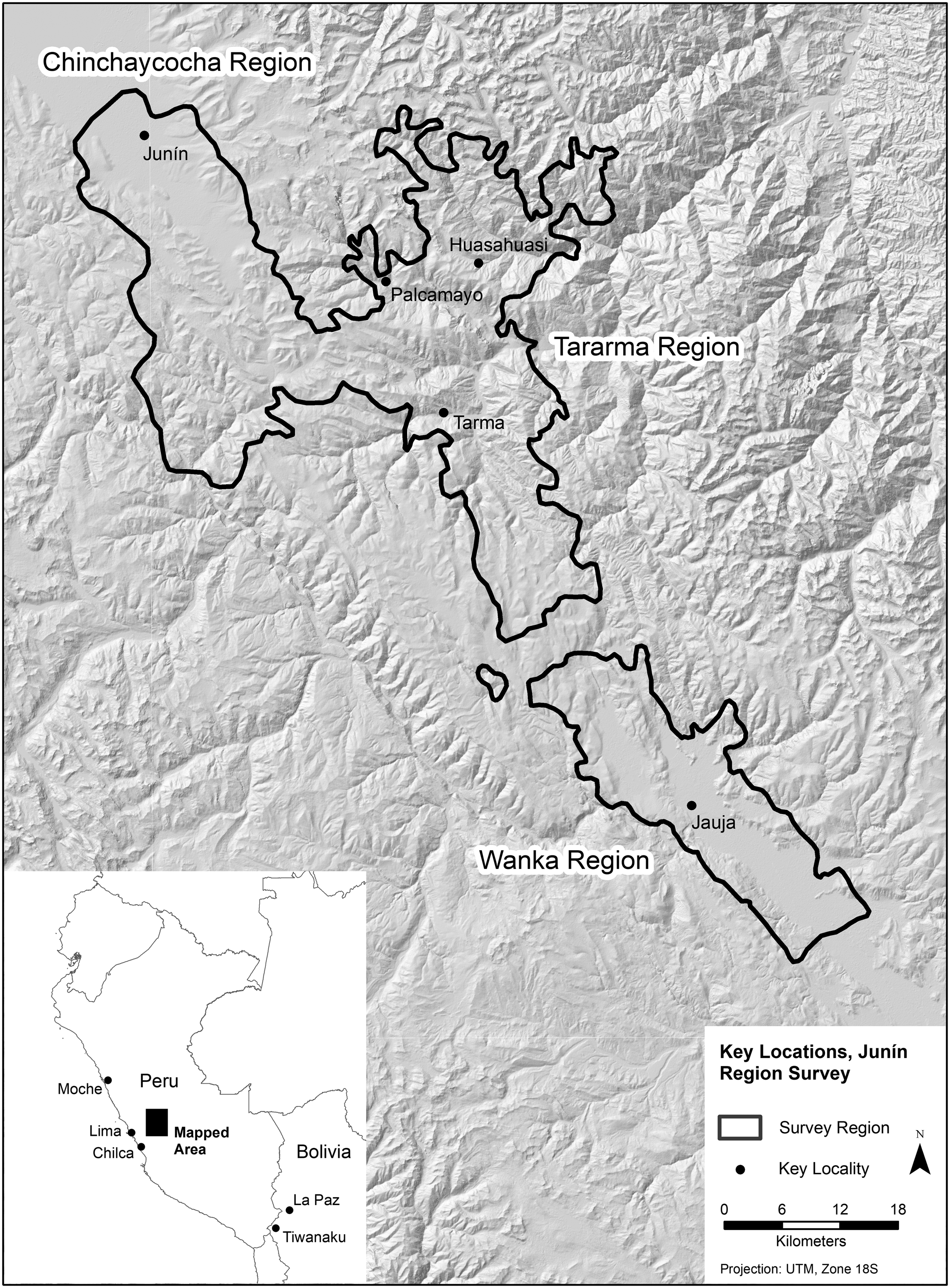

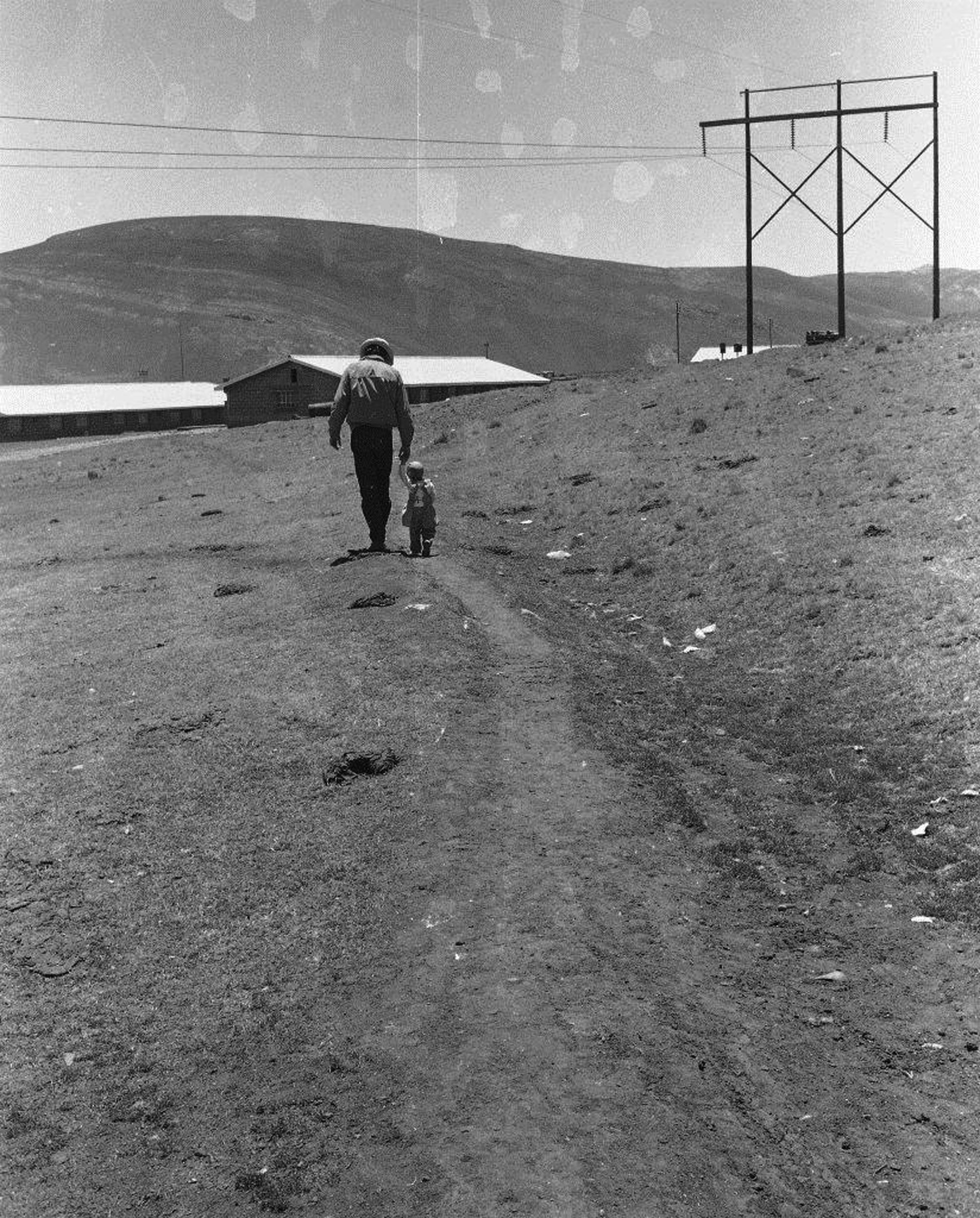

Following the sunken fields project, Jeff and Mary returned to the Basin of Mexico to complete the Chalco-Xochimilco survey and to conduct a survey of the Zumpango region in the northwestern basin (Figure 2). But Peru began to beckon once again. Jeff had met Peruvian archaeologist Ramiro Matos, at the time a professor of anthropology in Peru, who visited the Texcoco region survey project in 1967. Matos expressed an interest in seeing a regional survey conducted in the central highlands of his own country. Despite quite a backlog of data that needed to be written up, Jeff's interest in conducting a regional survey in the Peruvian highlands while he was still young enough to work in such rugged terrain and high altitudes convinced him to pursue a survey in the Junín area of Peru. Developing the project with Matos as a co-principal investigator provided strong project expertise in the cultures, land use patterns, and archaeology of the Peruvian highlands. Jeff and Matos secured NSF funds for two long field seasons of survey in 1975 and 1976 (Figure 9). With Mary, the Parsons’ newborn daughter Apphia, and students from the US and Peru, they began the first year of the Junín survey in June 1975, continuing until December of that year (Parsons Reference Parsons2019a:215–216). The large area surveyed was geographically and ecologically complex, composed of three different environmental zones that ranged from 2,800–4,600 m in elevation. The project focused on surveying the eastern part of the Chinchaycocha-Tarama regions (including the town of Tarma) and the Wanka region in 1975, both kichwa zones characterized by dissected small valleys and intervening ridges at the upper altitudinal limits for trees and shrubs (Parsons Reference Parsons2009b:10). In 1976, the project surveyed the western portion of the Chinchaycocha-Tarama regions (including the town of Junín), lying primarily in the puna grasslands on rolling hills above the tree line, and part of the northeastern part that region (including the town of Husahuasi) comprising cloud forest descending east from the puna towards Amazon Basin (Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 10. Jeff and Apphia Parsons, walking in the puna near Lake Junín, Peru, 1976. Photograph by Mary Parsons.

Figure 11. Jeff reading to Apphia Parsons, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1977. Photograph by Mary Parsons.

Survey in the Peruvian highlands was challenging. Crews worked at high altitudes in terrain that often was steep and difficult to negotiate on foot let alone by vehicle. Temperatures often were low, occasionally dropping well below freezing at night even in living quarters. Weather included brief squalls of snow, hail, sleet, and cold rain that complicated fieldwork. The archaeology was also quite different than that found in the Basin of Mexico, with many more standing stone walls, sites that featured large groups of storage structures, large sites often located on remote ridge tops, and small sites in and near suitable agricultural land. During the second year of survey, crews worked in the puna grassland and in cloud forest (in part of the kichwa), reducing surface visibility considerably. Jeff adjusted field methods accordingly to accommodate new logistical and archaeological challenges. A few problems with local residents—in one case accusing a field crew of being pistachos (light-skinned alien beings who preyed on stray local people) and attacking the crew with stones, in another threatening a crew and refusing access to part of the survey area—introduced other challenges, some overcome in part by articles in a local newspaper publicizing the survey. Through it all, Jeff took things in stride, maintaining his even temper and enthusiasm amid genuine concern, particularly about threats to project personnel.

Settlement patterns in the Junín area provided insights on the evolution of pre-Inka, Inka, and post-Inka complex societies. Evidence included indications of vertical interaction between pastoralists and agriculturalists, marked by sites occurring at the juncture between puna and kichwa, as well as smaller sites located on valley floors that likely were used for crop production during pre-Columbian times. The surveys in highland Peru highlighted for Jeff the distinctiveness of Mesoamerica for its lack of large, domesticated herbivores and pastoralism (Parsons Reference Parsons, Staller and Carrasco2010b). Also noteworthy were marked differences in late pre-Columbian sites from different sections of the survey area, consistent with sociopolitical differences documented in sixteenth-century ethnohistoric sources (Parsons Reference Parsons2019a:221). Results of the survey appeared in two typically impressive monographs that defined regional settlement in an area largely unknown archaeologically prior to the Junín survey (Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Matos M. and Hastings2000, Reference Parsons, Matos M. and Hastings2013). This work would provide a basis for the Upper Mantaro Archaeological Research Project, a multi-year study begun in 1978 and directed by Timothy Earle at the University of California, Los Angeles, that provided compelling additional insights on the region.

Jeff worked hard to develop expertise in the Andes, particularly in the 1975–1976 surveys. He particularly liked the central Andes and found the role of altitudinally based adaptation of great interest in addition to providing further basis for comparing sociocultural evolution in the Andes and Mesoamerica. Unfortunately, civil unrest was descending on Peru and terrorists would roam the highlands, including the area where the surveys occurred, in the 1980s and 1990s. Jeff reluctantly decided to delay any follow-up work due to those dangerous conditions. By the time the terrorist activities subsided in the early 1990s, he felt that for him the physical demands of working at such high altitudes were too great and he never returned to the field in Peru.

BACK TO THE BASIN: EXCAVATION, ETHNOGRAPHY, AND OFF-SITE SURVEY

Following field seasons in Peru in the mid-1970s, Jeff Parsons returned to where for him it all began, the Basin of Mexico. He had developed research questions over the years that he hoped to investigate further. Indeed, part of the justification for full-coverage regional survey was to generate a basis for selecting sites for further examination, notably through excavation. In 1980, Jeff received NSF support to excavate chinampa sites in the southeastern Basin of Mexico, near modern-day Chalco. That project was delayed for one year while NSF negotiated with the Mexican government over payment of a new fee on research funds. The field season finally began in 1981, running from May through November.

The excavations in 1981 focused on a series of questions about the many sites discovered during archaeological survey near the former shore of Lake Chalco. Jeff was uncertain about the function of some of the sites—were they residential sites for chinampa farmers, communities of people hunting and fishing on the lake, temporary residences of transient occupants, or something else? He wanted to understand how these sites might provide additional understanding of the creation and contribution of chinampa agriculture in the area. The six-month field season focused on testing these sites, including part of the administrative center of Xico, to address these and other questions (Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Parsons, Popper, Taft and Farrington1985). Stratigraphy ended up being deep and complex, created in some cases by an enormous accumulation of well-preserved organic materials from dominant cultigens, such as maize and beans. Some test pits exceeded two meters and never reached sterile levels, encountering groundwater before running out of cultural material. The project examined a range of different sites, including those that functioned as residences for people working in pre-Columbian chinampas.

Shortly after the chinampa excavations, Jeff moved into administrative duties at the Museum of Anthropology (Director, 1983–1986; Associate Director, 1990–1991) and the Program in Latin American and Caribbean Studies (Acting Director 1991–1992) at the University of Michigan. Opportunities for long periods of uninterrupted fieldwork, which characterized many of his projects into the early 1980s, seemed to have come to an end, at least temporarily. To maintain some field presence, Jeff decided on a different strategy. By the 1980s he had noticed that many traditional rural lifeways observed in the Teotihuacan Valley and the Basin of Mexico two decades earlier had begun to disappear amid modern development (Parsons Reference Parsons2009b:8). Needing to limit his absence from campus and his administrative responsibilities, Jeff decided to document certain disappearing activities ethnographically in projects that required shorter field seasons.

The first ethnographic study, conducted by Jeff and Mary, focused on maguey production and use in the Mesquital, lying just north of the Basin of Mexico and hosting people who still largely spoke Otomí at the time (Figure 2; Parsons and Parsons Reference Parsons and Parsons1990). Fieldwork funded by the University of Michigan occurred in 1984 and 1986 and focused on the village of Orizabita. Maguey, which refers to several species of Agave prevalent in highland central Mexico, had long been an interest of Jeff's because of the critical role it played economically in parts of the Basin of Mexico lacking sufficient water, soil quality, or both to grow other crops. Jeff and Mary focused primarily on the production of ixtle, the fiber extracted from the leaves (pencas) of magueys and used for various purposes, as well as pulque, a fermented beverage made from maguey sap; they also documented several, less-frequent uses, such as building construction. At the time of fieldwork, many younger residents of Orizabita were losing the ability to speak Otomí as well as many maguey processing skills, such as drop spinning with spindle whorls used to create thread from ixtle. The Parsons’ ethnographic work contributed to understanding the potentially vital role of maguey in pre-Columbian economies.

The next ethnographic study that Jeff undertook was salt making in Nexquipayac, a village on the ancient shore of Lake Texcoco just south of the Teotihuacan region (Figure 2). He first encountered traditional salt makers in 1963 during the Teotihuacan Valley survey. While visiting the area again in 1987, he noted only a few salt makers remained, so with funds from the National Geographic Society (NGS) in 1988 he conducted a study of salt production (Parsons Reference Parsons2001a). Part of his motivation for this study, apart from documenting this disappearing activity, was his hope that understanding the salt making process might help interpret archaeological remains, such as certain sites from near the ancient shore of Lake Texcoco. Working with two traditional salt makers, Jeff documented the process of salt making from harvesting the right type of salinized soil to packing and leaching soil in specially designed pits to boiling the resulting brine to produce salt of varying colors and qualities. A few salt makers were still working when Jeff and three colleagues visited Nexquipayac in 2007, but the numbers had declined further.

Jeff conducted a third ethnographic study in 1992, this time focusing on collecting aquatic insects (Parsons Reference Parsons2006). He had first encountered this activity in 1967 while surveying in the southern part of the Texcoco region, near the village of Chimalhuacan (Figure 2). At that time, he noted a few men pushing small nets through the shallow remnant waters of Lake Texcoco. They sold the insects collected to shops in Mexico City as feed for pet birds. Jeff visited Chimalhuacan again in 1987 and 1991 and noted that this activity was rapidly disappearing. Once again with funds from the NGS, he contacted the last person collecting insects in this portion of former lake. Although this activity had all but disappeared by 1992, Sigvald Linné (Reference Linné1948) had documented netting and other activities for extracting resources from the lake system in the 1930s. The data Jeff collected helped to augment Linné's description of the behavior observed several decades earlier. He argued that exploiting protein-rich lacustrine resources complemented seed and xerophytic (primarily maguey) agriculture in the Basin of Mexico, helping us understand how this region sustained large pre-Hispanic cities and dense populations without a pastoral component to the economy present in other world regions where early cities and states arose (Parsons Reference Parsons, Staller and Carrasco2010b).

In the late 1990s, Jeff was reconsidering two characteristics of the Basin of Mexico settlement pattern surveys that he felt needed to be addressed. One was the potential significance of sparse scatters of cultural material, previously noted but not recorded as sites. The other was the possible uses of the pre-Columbian lakebed by residents of the region. Both questions arose from his recent ethnographic studies of salt making and insect collecting, resource extraction activities that left only subtle physical evidence. Moreover, brief forays into portions of lakebed on earlier surveys in the basin revealed the presence of scattered artifacts—usually insufficient to define a site by the survey methods Jeff had devised, but considering the minimal physical evidence left by modern salt making and insect collecting justifying a further look. He decided to conduct an off-site survey, something he had never done before. To prepare, Jeff visited three ongoing projects using this approach, in Mongolia, Australia, and Italy (Parsons Reference Parsons2019a:322). Confident he could devise such a method for part of the Lake Texcoco lakebed that remained largely intact—in part due to its designation as a protected area by the Mexican government—Jeff secured NGS funds to support fieldwork for two months in 2003, conducted in collaboration with Luis Morett from the Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo in Mexico. The project located roughly 1,100 artifacts and artifact clusters, a shrine (consisting of remnants of a likely wooden platform anchored and supported by wooden stakes), and numerous elaborate ceramic and lithic artifacts (Parsons and Morett Reference Parsons, Morett and Williams2005).

Jeff never got an opportunity to expand on his earlier chinampa investigations. Unfortunately, he was racing against development and development was winning, certainly in the southern basin where the chinampa sites of interest occurred. This situation was a disappointment. Fortunately, the other projects were valuable replacements. The three ethnographies worked out better than expected, providing not only useful information for others but also much greater understanding of maguey production and lake resource exploitation, both in the present and in the past. Part of the reason they yielded such rich results was the relationship Jeff developed with his informants, his genuine interest and kind manner repaid with rich data as locals treated Jeff like a friend and member of the community. Featuring some of this fieldwork as videos in ethnographic portions of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico was further testimony to its significance. Bill Sanders would later remark that of all of Jeff's impressive accomplishments, those three ethnographic studies may have been the greatest.

RETIREMENT: CONTINUING CONTRIBUTIONS MIXED WITH PERSONAL TIME

Jeff Parsons retired from the University of Michigan in 2006 after 40 years as a curator at the Museum of Anthropology and professor in the Department of Anthropology. He remained sharp and active, but he felt it was time to step aside and make way for the next generation. Jeff had achieved much, recognized for his research contributions by the American Anthropological Association with the Alfred V. Kidder Award in 1998, and by the University of Michigan with the Distinguished Faculty Achievement Award in 2002. He would later receive the Society for American Archaeology Excellence in Latin American and Caribbean Archaeology Award in 2015. Colleagues had assembled a volume in his honor (Blanton Reference Blanton2005), testimony to his remarkable career as a researcher, teacher, and innovator who helped change the course of archaeology.

Jeff stayed busy during retirement, mixing a steady flow of professional pursuits with personal activities. Although he had reduced the pace of the former, his interest in many anthropological questions that had brought him to archaeology more than four decades earlier persisted. He maintained a presence in the Department of Anthropology, interacting with current and other emeritus faculty about assorted problems of interest. Jeff continued his contributions to Ancient Mesoamerica, serving on the editorial board from the journal's inception in 1990 until his passing. Not surprisingly, he engaged the profession at the same high level that had marked his career.

Jeff regularly attended professional conferences. Although he saw these as opportunities to reconnect with the growing number of friends he had made over his remarkable career, he almost always participated in the meetings, either presenting a paper or serving as a discussant for other presentations. In retirement, Jeff also lectured at specially organized events, or in response to invitations to talk, often in Mexico and Peru. The frequency with which he was invited to present papers, provide commentary, and lecture attests to both his professional stature and, in the case of lecture series, to his continuing contribution to the discipline. Invitations to lecture in Latin America also testify to the respect he received in these countries where he had spent so much of his professional life, and the fondness of many of his colleagues based on a career of collaboration, kindness, and generosity. As when he was an active faculty member, Jeff reached out to students in a way that few had, his willingness to share data and insights creating lasting memories among rising scholars as it had decades before.

Most of Jeff's fieldwork after he retired focused on assessing the deteriorating condition of the archaeological record in the Basin of Mexico (Parsons Reference Parsons2015). Travel to various portions of the basin in 2008–2010, 2018, and 2019 included visits to selected noteworthy sites in the region. Several trips to Peru occurred during that same general period, mostly aimed at addressing curation of cultural material he had collected during his 1970, 1975, and 1976 field seasons. Trips to the basin were particularly remarkable in that Jeff visited sites all over the region, including those surveyed by the Sanders and Blanton projects. When visiting sites from his own surveys, Jeff often would begin describing a site in detail before arriving at it, his recollections of the archaeological remains often augmented by characteristics of surrounding landforms, local communities, dominant land use patterns at the time of survey, and anticipated threats to the archaeological record. This was particularly remarkable because in many cases he had not seen these sites for three or four decades. He often described other remains that occurred near a site being visited, proposing possible settlement systems that gave rise to the archaeological record. Invariably, he would recall stories of the people involved in a site's discovery and recording, often featuring crews on his own projects and, in the case of the Teotihuacan Valley, his adventures with other field crew members exploring the countryside (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Jeff and Mary Parsons, taking a brief break from visiting archaeological sites in the Texcoco region, Basin of Mexico, 2008. Photograph by Gorenflo.

Jeff's greatest professional time commitment during retirement probably involved research and writing. Those who work on large projects often have a backlog of material to publish. Beginning in 1966, Jeff was almost constantly in the field for nearly a decade, and then was frequently in the field until the early 2000s. One of his greatest concerns was writing up the results of various projects. The settlement pattern monograph for the Zumpango region (Parsons Reference Parsons2008b) and the second volume for the Junín survey (Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Matos M. and Hastings2013) appeared after his retirement, signs of his commitment to continue to produce documents of the same detail and quality as those published when he was a faculty member. Always sensitive to making his work accessible to a broad range of readers, he sought to re-issue many of his earlier monographs in Spanish (e.g., Parsons Reference Parsons2008a), an ongoing effort interrupted by his passing last year. Jeff was working on two final monographs at time of his death, one on the 1981 chinampa excavations and another on the 2003 lakebed survey; both are scheduled for completion in coming years. As with all his projects, Jeff shared access to data and collections from all of his studies with students and colleagues and encouraged and supported their research. In addition to academic research, his survey data have been critical to salvage archaeology in the Basin of Mexico as those efforts struggled to stay one step ahead of development (García et al. Reference García, Gamboa, Vélez Saldaña, Gallut and Peralta2005, Reference García, Gamboa and Vélez Saldaña2015).

One of Jeff's main activities during retirement was compiling records on his family's history. His focus usually was on western Maine, where his father grew up on a farm that had been in the family since the late eighteenth century; the research and publication of those materials was often in collaboration with Mary. As noted above, Jeff came from a family that had documented their lives systematically, in written form (often letters and diaries) and photographs, and it was the discovery of these materials while visiting the family farm one year that inspired this undertaking. The result was several volumes based on accounts of growing up on a rural farm in western Maine during the early twentieth century (Parsons Reference Parsons2009a); life on farms and ranches in rural Alberta, Canada, Connecticut, and New York (Parsons Reference Parsons2013); experiences in rural Maine and other parts of the United States during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Parsons and Parsons Reference Parsons and Parsons2018); and life in various parts of the United States during the 1930s (Parsons Reference Parsons2019b).

In retirement, Jeff seemed to mix business with pleasure quite effectively. He remained active professionally, to the point of continuing to do some fieldwork. But he combined personal travel and activities with professional. Jeff and Mary spent summers in New England, living in and working on the Parson family farmhouse in South Paris, Maine. The demands of maintaining a house whose construction began more than two centuries earlier were considerable, but Jeff was no stranger to hard work, and he threw himself into these tasks with the same energy he committed to his professional activities. The Maine visits also involved various activities found in rural New England, such as attending public suppers, performances at the Celebration Barn Theater, and bluegrass festivals. Part of Jeff and Mary's summers was spent in Jaffrey, New Hampshire, at the lake cottage that Mary's family owns, walking and reading, picking and eating blueberries, playing tennis on the clay court in the forest, and playing Uncle Jeff poker (something Jeff taught to the next generation at a young age). Jeff and Mary traveled for pleasure, often to Europe to visit their daughter Apphia, who resides in London with her husband (Figures 13 and 14).

Figure 13. Jeff and Apphia Parsons painting the Parsons family farmhouse, South Paris, Maine, 1977. Photograph by Mary Parsons.

Figure 14. Jeff and Apphia Parsons, Christmas, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1993. Photograph by Mary Parsons.

In all, the mix of activities during retirement from the university seemed to suit Jeff. He joked about being invited to comment in conferences as one of the grand old men of archaeology, but in fact he remained so connected to and aware of current archaeology that his presence was actively sought for his expertise. Consistent with his ability to describe archaeological sites he had not seen for 40 years, Jeff remained remarkably sharp throughout his retirement.

A FRIEND AND COLLEAGUE SORELY MISSED

Jeff Parsons died on a Friday in late March after a relatively brief stay in the University of Michigan hospital. His passing was a surprise to many who thought, or maybe hoped, that it simply was not his time. At 81, Jeff was still writing, actively participating in professional conferences, working on monographs to document past fieldwork, and helping to assess the condition of the archaeological record in the Basin of Mexico. Another trip to the basin was planned for summer or fall 2021, COVID-19 pandemic permitting.

The shock of Jeff's death was buffered, in part at least, by the enormous outpouring of love, respect, and admiration that came from many corners of the archaeological and anthropological community, and from many other individuals who had known him—colleagues, former students, collaborators, and friends. Certainly, one theme of these messages was his considerable contributions to archaeology and anthropology but what dominated most messages was people reaching out to recall his personal qualities. Jeff's passing was a reminder to many of us that he had accomplished so much as a congenial, gentle soul. His kindness and easygoing nature seemed to infuse all corners of his life, including his professional career. Jeff Parsons had achieved great success without sacrificing his personal warmth and integrity.

Jeff is survived by his wife and partner in life for 55 years, Mary, and by their daughter Apphia and son-in-law Daniel. As many readers of this essay will know, Mary also was Jeff's main research collaborator for decades, primarily in Mexico and Peru. Watching Jeff and Mary walk on an archaeological site in the Basin of Mexico was indeed something to behold, in their youth and in retirement. In revisiting sites discovered decades earlier, they both knew the survey and observational drill better than anyone, having practiced it thousands of times over many years, and they seemed to switch to auto-pilot as soon as they encountered archaeological remains. Both shared a deep-seated affection for the region, its archaeology, and its people, many of the latter descendants of those who had created the sites so many centuries earlier. Mary and Jeff also shared frustration with the enormous loss of the prehistoric record that they had done so much to define. Jeff would occasionally comment with amazement that they could do so much fieldwork from the late 1960s through the mid-1970s (e.g., Parsons Reference Parsons2019a:108), an observation made even more amazing when one remembers that it truly was they and that Mary usually was with him step-by-step (see Parsons Reference Parsons2019a). Her collaboration in many phases of Jeff's career is a testimony to a shared life based on love and professional respect. Apphia grew up in a world most children only could have imagined, going to the field for the first time in Peru when she was only three months old (Parsons Reference Parsons2021). Her professional skills as an adult in Spanish and French translation surely are rooted in those early years being surrounded by Spanish, and occasionally also by speakers of Quechua, Otomí, or other Indigenous languages.

Jeff also is survived by a brother and sister, nieces and nephews, other family members, and a host of students and colleagues, all of whom still feel his loss. It was many in his professional family who reached out when they heard the news of his passing and it is here that the breadth of his connection to others becomes clearer. Certainly, in part this reflects his contribution to regional studies in archaeology, both in getting the data from the field through analyzing and publishing those data. It also surely reflects having worked in a broad range of localities with many different researchers—in Mexico and Peru certainly, but also in Argentina, Australia, Bolivia, Egypt, Guatemala, Iceland, Italy, Mongolia, and various parts of the United States. And it no doubt reflects having been a university professor for more than four decades; time depth usually helps to generate a broad network of connections. But in many cases, people who reached out following Jeff's death were individuals with whom he had merely interacted one way or another, people who simply were touched by the person he was.

We would be remiss if we did not describe something of the funny, fun-loving, quirky individual that was Jeffrey R. Parsons. Part of this likely came from his teenage years when he obligingly let a friend polish the back seat of his father's car so when Jeff turned the corner sharply the young lady in the back seat slid closer to her date. Connections to his youth included references to his beloved 1950 Hudson Pacemaker, a car with a peculiar model name that ironically was transitioning to an archaeological artifact as he drove it into the mid-1960s (Figure 15). He would occasionally offer trivia from old radio shows he listened to in his youth. Who knew that the Lone Ranger's nephew's horse was named Victor or, for that matter, that he even had a nephew? Or the weight of the main character in “The Fat Man”: “There he goes into a drugstore. He steps on the scales…Weight, 239 pounds…fortune, danger!” Yes, Jeff could recite the entire introduction. As a faculty member, he would show and narrate films at departmental parties depicting the train trips of his youth in Mexico along curving sections of track, announcing “the front of the train from the back of the train” and, not surprisingly, “the back of the train from the front of the train.” And he would run films of excavations sped up and in reverse, to show soil in back dirt leap onto shovels and then back into the site area. Jeff's good humor continued in the field. His ability to walk long distances was legendary among his survey crew members, a skill born as a youngster on walks with his father but refined during his first seasons of fieldwork. Jeff and other crew members surveying the Teotihuacan Valley used to go on walks around the valley on their days off; he would claim later that there was a statue of another crew member and him planned for the summit of Cerro Chiconautla on the edge of the valley after they climbed it one weekend. As a graduate student of Jeff's, Liz Brumfiel took up jogging prior to going to the field to survey on one of his projects (Nichols Reference Nichols and Brereton2006:111). Jeff sent a postcard to a former student showing the bridge in Buenos Aires where the two of them were mugged at knife point, noting that the former student might want to add it to his collection of fieldwork memories. After being pulled over with Mary and a colleague by police on the outskirts of Mexico City and forced to a large yard of wrecked cars for a tense few minutes of extortion (mordida, “the bite”), he would occasionally recall the head public servant involved, referring to him as “Officer Larry.” Perhaps the sense of humor was his way of dealing with some of the challenges of life. What else could explain settling down to offer running commentary on one of the Hell Boy movies after a long day of visiting the disappearing archaeological record of the Basin of Mexico? His adopted Mexican name “Joaquin” had ceased to be used except by a few who remembered his early work in the Teotihuacan Valley, though it was replaced by “Joaquincito” for at least one Mexican colleague, further testimony to Jeff's light-hearted ways. In the end, Jeff Parsons was a good person to be around. He worked hard and he worked his crews hard, but they showed up the next day for more of the same, and in many cases the next season as well, because he kept it interesting and fun.

Figure 15. Jeff Parsons and his beloved Hudson Pacemaker, State College, Pennsylvania, 1965. Photographer unknown.

Jeff Parsons often spoke of “being at the right place at the right time” and of his “great good fortune” in having been able to pursue a career he loved. One can find this expressed in his writings where he reflects on his life in archaeology (e.g., Parsons Reference Parsons2022). Equally true is how Jeff capitalized on opportunities, in many instances taking them in different directions and further than anyone would have imagined. For archaeology, and indeed for anthropology, the results of those efforts often were remarkable advances in our understanding of ancient regional organization through his refinement of settlement pattern survey methodology that he subsequently applied to key parts of the archaeological world, providing a basis for interpretations that significantly enhanced our understanding of important places. Jeff Parsons indeed did enjoy good fortune in his life and his career. Most successful people do. As we look back on his passing, and his legacy, as a student, teacher, colleague, and friend, in the end perhaps it is we who have had the greatest good fortune in having known and worked with him (Figure 16).

Figure 16. Jeffrey R. Parsons, 1939–2021. Photograph by Mary Parsons.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We greatly appreciated comments from Mary Parsons and Apphia Parsons on a draft of this testimony to the life and career of Jeffrey R. Parsons. This remembrance has benefitted from conversations over the years with several of Jeff's friends and colleagues, including Liz Brumfiel, Oralia Cabrera, Ruben Cabrera, Bob Cobean, Wes Cowan, George Cowgill, Dick Diehl, Susan Evans, Dick Ford, Kirk French, Jimmy Griffin, Chuck Hastings, Charlie Kolb, Claire Milner, Ian Robertson, Bill Sanders, Lili Sanders, Carla Sinopoli, Yoko Sugiura, and Henry Wright. We are grateful to Nan Gonlin and the editorial staff of Ancient Mesoamerica for their willingness to publish this account of Jeff's life in such a timely manner.

APPENDIX

Additional works by Jeffrey R. Parsons that were not cited in this text are provided below.