Dementia is one of the most common neurodegenerative disorders. Rapid cognitive decline over time increases the risk of dementia(Reference Petersen, Smith and Waring1) and may precede a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease by as much as 10 years(Reference Geschwind, Robidoux and Alarcon2).

At present, there is no treatment that can stop the progress of dementia. In order to postpone or prevent cognitive decline and eventually dementia at old age, intervention is required already at middle age. Therefore, it is important to identify modifiable risk factors (e.g. diet, physical activity and smoking) for cognitive decline in middle-aged populations. Although the underlying mechanism is not yet fully understood, alcohol consumption is a possible determinant of cognitive impairment and dementia. A beneficial effect of (moderate) alcohol consumption on cognitive function has been found in cross-sectional studies in middle-aged(Reference Cerhan, Folsom and Mortimer3) and older subjects(Reference Espeland, Coker and Wallace4–Reference Vincze, Almos and Boda6), and in some(Reference Stampfer, Kang and Chen7–Reference Espeland, Gu and Masaki10), but not all(Reference Barberger-Gateau, Raffaitin and Letenneur11), prospective studies among the elderly. In one study, including both middle-aged and elderly individuals (aged 40–98 years), alcohol consumption has been associated with better cognitive performance and less cognitive decline over time(Reference Wright, Elkind and Luo12). Reviews and meta-analyses on alcohol consumption and cognitive decline and the incidence of dementia have concluded that light to moderate drinking was associated with a lower risk of dementia and cognitive impairment, but not with cognitive decline(Reference Anstey, Mack and Cherbuin13–Reference Peters, Peters and Warner16).

Only a limited number of studies have examined the consumption of different types of alcoholic beverages in relation to dementia(Reference Neafsey and Collins14), and only in elderly populations. Conflicting results have been reported: in some studies, especially wine was associated with a reduced risk of dementia(Reference Truelsen, Thudium and Gronbaek17–Reference Luchsinger, Tang and Siddiqui19), while in other studies, no difference was observed between different sources of alcohol and the risk of dementia(Reference Ruitenberg, van Swieten and Witteman9, Reference Mukamal, Kuller and Fitzpatrick20). In 2002, we reported the associations between total alcohol consumption and cognitive function(Reference Kalmijn, van Boxtel and Verschuren21). At that time, only one measurement of cognitive function was available and no distinction between different types of alcoholic beverages was made. We observed that in women, moderate alcohol consumption was associated with better speed of cognitive processes and better flexibility. The observed associations can be due to alcohol itself, other substances in alcoholic beverages (e.g. polyphenols in red wine) or confounding factors: alcohol consumption may be associated with cognitive function through the associations with other lifestyle factors(Reference Letenneur, Larrieu and Barberger-Gateau22). In the present study, we evaluated the associations between the habitual consumption of alcoholic beverages and 5-year changes in cognitive function in a cohort of middle-aged men and women. In addition, we were able to distinguish between different types of alcoholic beverages in association with the change in cognitive function, controlling for a wide range of possible confounding factors. By studying the consumption of different types of alcoholic beverages in association with cognitive decline, while controlling for other lifestyle factors, more evidence can be obtained whether or not it is alcohol itself that affects cognitive function. If alcohol itself is responsible for an association with the change in cognitive function, we expect an association for total consumption and similar associations for all types of alcoholic beverages.

Subjects and methods

Population

The Doetinchem Cohort Study (DCS)(Reference Verschuren, Blokstra and Picavet23) is an ongoing prospective study among inhabitants of Doetinchem, a small town in the eastern part of The Netherlands. The cohort includes a general population sample of 7769 men and women aged 20–59 years during the baseline examination (1987–91). A total of second (1993–7), third (1998–2002) and fourth (2003–7) examination rounds were completed. The present study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Helsinki Declaration. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the external Medical Ethics Committee of the Netherlands Organization of Applied Scientific Research (TNO). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Details on the DCS have been described elsewhere(Reference Verschuren, Blokstra and Picavet23).

Halfway the second examination round, in 1995, cognitive testing for DCS participants aged 45 years and older was introduced. Between 1995 and 2002 (baseline), 3350 respondents aged 43–70 years, 96 % of all respondents invited, participated in cognitive testing for the first time. At 5 years later (2000–7, follow-up), 2690 of them (80 %) participated in cognitive testing again. Participants who reported to have had a stroke (n 77) were excluded, leaving a total of 2613 participants (1288 men and 1325 women) with two cognitive measurements for the present analyses.

Cognitive tests

The neuropsychological test battery included four tests: the 15 Words Verbal Learning Test (measures memory: immediate and delayed recall), the Stroop Colour-Word Test (measures speed and cognitive flexibility), the Word Fluency Test (measures semantic memory) and the Letter Digit Substitution Test (measures speed). These tests have been described in more detail elsewhere(Reference Nooyens, Bueno-de-Mesquita and van Boxtel24). The tests are sensitive to age, including the middle-age range, and have been used in several other large-scale studies on cognitive function(Reference Møller, Cluitmans and Rasmussen25–Reference de Groot, de Leeuw and Oudkerk27).

Assessment of alcohol consumption

A validated, self-administered, semi-quantitative 178-item FFQ was used to assess the habitual consumption during the previous year. This questionnaire was developed for the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition(Reference Ocké, Bueno-de-Mesquita and Goddijn28). Participants were asked the number of glasses of beer, white wine, red wine, port/sherry/vermouth and spirits they had consumed. Participants indicated their consumption frequency on a daily/weekly/monthly/yearly scale or as never consumed. Alcohol consumption was assessed as the sum of frequencies of five types of alcoholic beverages: beer; white wine; red wine (including rosé wine); fortified wine (e.g. port and sherry); spirits. Spearman's correlation coefficients for relative validity (with 12 monthly 24 h recalls) for alcoholic beverages were 0·74 and 0·87 for men and women, respectively(Reference Ocké, Bueno-de-Mesquita and Goddijn28). In order to create a more reliable measure for habitual consumption of alcoholic beverages, we averaged the data assessed at baseline and follow-up. In order to describe the dose–response associations and to allow non-linear associations, we defined categories of consumption of alcoholic beverages, based on the distribution in our dataset. For every type of alcoholic beverage, there was one category with abstainers (not consuming the specific type of alcoholic beverage, thereby including former drinkers). Consumers of the specific type of alcoholic beverage were divided into quintiles.

Other measures

During the physical examination at the research centre, height, weight, waist circumference and blood pressure were measured, and non-fasting blood samples were obtained(Reference Verschuren, Blokstra and Picavet23), to determine serum total and HDL-cholesterol concentrations. Information on demographic characteristics (e.g. age, education and marital status), lifestyle factors (e.g. smoking and physical activity), medical history of chronic diseases and medication use was collected using standardised questionnaires. Educational level was assessed as the highest level reached and classified into five categories. Smoking status was defined based on cigarette smoking status at baseline and follow-up – never smoker, ex-smoker (quit before baseline), recent quitter (quit after baseline), (re-)starters or current smoker – and the number of lifelong pack years was calculated for ever smokers(Reference Nooyens, van Gelder and Verschuren29). One pack-year corresponds to smoking twenty cigarettes per d for 1 year (or, for example, smoking one cigarette per d for 20 years). A four-level physical activity index (‘Cambridge’ physical activity index)(Reference Wareham, Jakes and Rennie30) was derived by combining occupational physical activity together with time spent on participating in cycling and other physical exercise, assessed by the use of the validated European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition questionnaire on physical activity(Reference Pols, Peeters and Ocke31). Based on the FFQ, energy intake from fat was computed based on nutritional values in the Dutch Food Composition Database(32), and recomputed into sex-specific energy residuals. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Dutch version(33) of the SF-36 (Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey)(Reference Ware and Sherbourne34). The scales ‘mental health’ and ‘vitality’ denote symptoms of depression. Scores on both scales range from 0 to 100 in which higher scores represent better (mental) health.

Statistical analyses

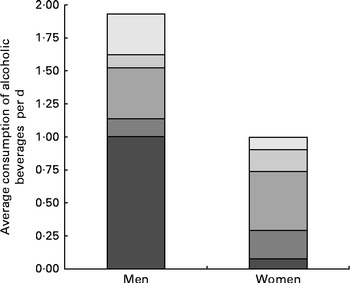

To give an overview of the distribution of the different types of alcoholic beverages consumed by men and women, stacked column charts were constructed.

For each cognitive test, a standardised z-score was computed at baseline and follow-up, based on the means and standard deviations of the total population at baseline. Compound scores(Reference Lezak35) were computed to reduce the number of psychometric variables and improve the robustness of the underlying test construct. Tests were combined based on their conceptual coherence derived from neuropsychological practice in performance testing, and clustering used in former studies(Reference Kalmijn, van Boxtel and Verschuren21, Reference Durga, van Boxtel and Schouten26, Reference van Boxtel, Buntinx and Houx36): global cognitive function (all cognitive tests combined) and three specific cognitive domains, i.e. memory function (Verbal Learning Test), information processing speed (Stroop Colour-Word Test and Letter Digit Substitution Test) and cognitive flexibility (i.e. higher-order information processing; Stroop Colour-Word Test)(Reference van Boxtel, Buntinx and Houx24).

Cognitive decline over follow-up was computed as the difference between the compound scores at baseline and follow-up, and compared between the reference category and each quantile of alcohol consumption using ANCOVA (PROC GLM). Although abstainers were included in all analyses, in these comparisons, the groups of individuals with the lowest consumption were used as reference groups, since the group of abstainers included former drinkers and was not always large enough to give robust estimates. Cognitive decline was analysed as a continuous outcome measure. In all analyses, adjustments were made for age, level of education (five categories) and the baseline level of cognitive function. To deduce the independent association between the consumption of alcoholic beverages and the change in cognitive function, additional adjustments were made for other lifestyle factors: smoking; physical activity; coffee consumption; tea consumption; fruit and vegetable intake; fat intake; total energy intake; vitality and mental health; marital status. These lifestyle-adjusted analyses will be presented.

To test effect modification by sex, we introduced an interaction term of alcohol intake and sex in a linear regression model (PROC MIXED), with age, level of education and baseline cognitive function as covariates. In the same way, we tested for effect modification by age (as a continuous variable), level of education, smoking status and hypertension (all as a categorical variable). If the significance level of the interaction term was < 0·10, the analyses were stratified by the effect modificator.

To test for a linear trend, P-for-trend analyses were performed using linear regression analyses (PROC MIXED) on median values of the consumption of alcoholic beverages in the quantiles in relation to cognitive decline(Reference W37). To examine non-linearity, the quadratic terms of median intakes in the categories (first centred around zero) were also entered into the model.

To test whether the consumption of different types of alcoholic beverages has different effects on the change in cognitive function, the former analyses were repeated with the types of alcoholic beverages as central determinants of change in cognitive function, controlling for the total consumption of the other types of alcoholic beverages.

In order to indicate whether cardiovascular factors (hypertension, serum HDL-cholesterol level, history of heart disease, diabetes, waist circumference and, for women only, oestrogen use) were part of the pathway by which consumption of alcoholic beverages is associated with changes in cognitive function, these factors were added to the regression models as covariables. For all covariables, the baseline measurement was used, except for smoking status.

As we did not test for dementia per se, we ran sensitivity analyses excluding data from individuals who scored lowest on global cognitive function at baseline or follow-up (lowest 2·5 %).

In order to elucidate the results, some additional analyses were performed. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis Systems statistical software package version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Results

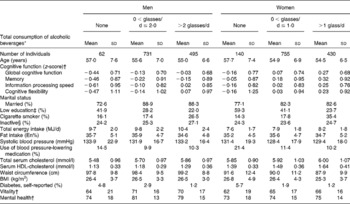

At baseline, men and women who drank alcoholic beverages were on average younger than individuals who did not drink alcoholic beverages (Table 1). In addition, they scored better on global cognitive function and all cognitive domains, were higher educated, were more often cigarette smokers, had a higher total energy intake and had higher serum HDL-cholesterol levels than non-drinkers. Consumption of alcoholic beverages was higher in men than in women: median intake of alcoholic beverages was 1·4 glasses/d (interquartile range 0·6–2·7) in men and 0·5 glasses/d (interquartile range 0·09–1·30) in women. Also, the relative consumption of different types of alcoholic beverages was different for men and women (see Fig. 1). Men mainly drank beer (52 % of total consumption), while women mainly drank red wine (45 % of total consumption), although the average consumption of red wine was similar in men and women.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the study population by categories of total alcohol intake (Mean values and standard deviations or percentages)

En%, percentage of energy.

* Reported average consumption of alcoholic beverages (glasses/d) at baseline and follow-up.

† Higher score = better.

‡ Only primary school or low vocational education.

§ Inactive was defined as the lowest two out of four categories in the physical activity index.

Fig. 1 Average consumption of different types of alcoholic beverages (glasses/d) in men and women (alcohol consumers only). ![]() , Spirits;

, Spirits; ![]() , fortified wine;

, fortified wine; ![]() , red wine;

, red wine; ![]() , white wine;

, white wine; ![]() , beer.

, beer.

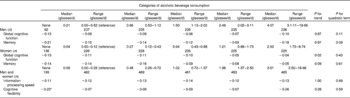

For the associations between the total consumption of alcohol beverages and the change in global cognitive function and memory, an interaction effect was present for sex (P= 0·04). Therefore, these associations were stratified by sex. Effect modifications by smoking status and level of education were not significant. Effect modifications by age and hypertension are mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2 5-year changes† in domains of cognitive function (z-scores) by total consumption of alcoholic beverages (Medians and ranges)

* Average change is different from the reference group (lowest user group) (P< 0·05).

† Average changes are adjusted for age, level of education, sex, baseline cognitive function, physical activity, smoking, energy intake, fat intake, coffee consumption, tea consumption, fruit and vegetable consumption, vitality and mental health, and marital status.

Total consumption of alcoholic beverages

Although not statistically significant, an inverse U-shaped association was observed between the total consumption of alcoholic beverages and the change in memory among men, with the smallest decline at about two to three drinks per d (Table 2). In women, a higher total consumption of alcoholic beverages was linearly associated with a smaller decline in global cognitive function (P= 0·02), with the smallest decline in the highest quantile (corresponding to about two to three drinks per d). Women who drank about two to three glasses of alcoholic beverages per d showed less than half the decline in global cognitive function compared with those who drank very little alcoholic beverages (>0–0·1 glasses/d). Individuals who did not consume alcoholic beverages declined stronger in cognitive flexibility than those who did consume alcoholic beverages (Table 2).

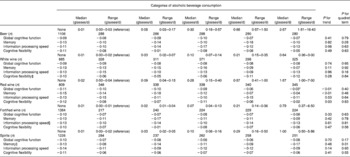

Types of alcoholic beverages

For most types of alcoholic beverages, no consistent associations with cognitive decline were observed (Table 3). Only for red wine consumption, a consistent linear relation over the whole range of intake was observed after adjustments for lifestyle factors: individuals who drank more red wine declined less in global cognitive function (P for trend < 0·01), memory (P for trend < 0·01) and cognitive flexibility (P= 0·03) over follow-up (Table 3). Individuals who drank about 1·5 glasses of red wine per d showed a smaller decline in global cognitive function compared with those with the lowest consumption of red wine (P= 0·02, Table 3). The associations between the consumption of red wine and domains of cognitive decline did hardly attenuate after additional adjustment for several cardiovascular risk factors (P for trends < 0·01, 0·01 and 0·03, respectively).

Table 3 5-year changes† in domains of cognitive function (z-scores) by consumption of different types of alcoholic beverages (Medians and ranges)

* Average change is different from the reference group (lowest user group) at P< 0·05.

† Average changes are adjusted for age, level of education, sex, baseline cognitive function, consumption of other alcoholic beverages, physical activity, smoking, energy intake, fat intake, coffee consumption, tea consumption, fruit and vegetable consumption, vitality and mental health, and marital status.

‡ A significant interaction term was observed for hypertension. However, both in hypertensives and non-hypertensives, the associations were not significant.

§ A significant interaction term was observed for age. However, both in younger and older individuals, the associations were not significant.

∥ A significant interaction term was observed for sex. However, both in men and women, the associations were not significant.

Sensitivity analyses excluding data from individuals who scored lowest on global cognitive function at baseline or follow-up did not essentially change the results.

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that moderate red wine consumption was associated with least decline in global cognitive function, memory function and cognitive flexibility. Consumption of other types of alcoholic beverages was not associated with cognitive decline. We are the first to show that, already at a relatively young age, moderate red wine consumption is prospectively associated with a smaller decline in cognitive function.

The major strengths of the present study are the prospective design, relatively young and healthy participants and the use of a sensitive cognitive test battery without a ceiling effect that was administered two times with a 5-year follow-up. In addition, different types of alcoholic beverages were determined, dietary habits were measured extensively in a large sample twice and lifestyle (e.g. diet) was assessed at a stage of life before cognitive impairment is present, so lifestyle was not altered as a result of cognitive function. Although the participants were still relatively young and healthy when they entered the study, a clear decline in cognitive function, with a wide range, was detected. In addition, the DCS has an extensive spectrum of variables assessed during the measurements. Therefore, we were able to adjust for a wide range of potential confounders, which is extremely important when studying alcohol consumption.

One of the potential drawbacks of the present study is the dropout of initial participants, although an 80 % response at follow-up is still high. Individuals who dropped out were on average older and scored lower on all cognitive domains than those who participated twice, but no differences in the average consumption of alcoholic beverages were observed and the associations between the consumption of alcoholic beverages and cognitive function at baseline were not essentially different between the two groups. Furthermore, it can be argued that the observed associations are the result of multiple testing. Therefore, we only emphasised results that pointed at a consistent association.

Furthermore, the observed associations between the total consumption of alcoholic beverages and red wine consumption and cognitive decline are in line with the results of studies that investigated the associations between the consumption of different types of alcoholic beverages and the development of dementia in the elderly(Reference Truelsen, Thudium and Gronbaek17–Reference Luchsinger, Tang and Siddiqui19) and the conclusion of a recent review on alcohol consumption and cognitive risk(Reference Neafsey and Collins14). In addition, these associations were similar for men and women in our population.

Factors other than alcohol may account for the associations between the consumption of (different types of) alcoholic beverages and cognitive function or the risk of dementia(Reference Letenneur, Larrieu and Barberger-Gateau22). In the present study, the consumption of alcoholic beverages was associated with other lifestyle behaviours, such as smoking and total energy intake. We were able to adjust analyses for a wide range of lifestyle factors. However, the associations between the total consumption of alcoholic beverages and red wine consumption and the change in cognitive function remained in the lifestyle-adjusted models.

Ad hoc analyses showed that at a lower total consumption of alcoholic beverages (up to three glasses per d, equal to the 95 % quantile in women and comparable to the consumption up to the highest category in men), the associations between the total consumption of alcoholic beverages and the change in global cognitive functions were similar for men and women (P for interaction = 0·85). Therefore, we expect that the inverse U-shaped association in men (indicated by the low P for quadratic term) may also apply for women if women would drink comparable amounts of alcoholic beverages.

Most previous studies have looked at total alcohol consumption(Reference Cerhan, Folsom and Mortimer3–Reference Anttila, Helkala and Viitanen8, Reference Espeland, Gu and Masaki10–Reference Wright, Elkind and Luo12, Reference Kalmijn, van Boxtel and Verschuren21), not at different types of alcoholic beverages in relation to cognitive function. Some studies that have looked at different types of alcoholic beverages (beer, wine and liquor) reported that consumption of wine was associated with a lower risk of dementia(Reference Truelsen, Thudium and Gronbaek17–Reference Luchsinger, Tang and Siddiqui19), while in other studies, no difference was observed between different sources of alcohol(Reference Ruitenberg, van Swieten and Witteman9, Reference Mukamal, Kuller and Fitzpatrick20). In the present study, the beneficial associations between the total consumption of alcoholic beverages and cognitive function were in particular determined by red wine consumption: In ad hoc analyses, the associations between the total consumption of alcoholic beverages and the decline in global cognitive function in women completely disappeared after adding red wine consumption to the linear regression model. We observed a beneficial association between red wine consumption and cognitive decline in both men and women, although total consumption of alcoholic beverages was associated with less strong cognitive decline in women only. In men, total consumption of alcoholic beverages included 20 % of red wine (and more than 50 % of beer); in women, this was 45 %. Therefore, a possible explanation for the lack of an association between the total consumption of alcoholic beverages and cognitive function or cognitive decline in our male participants and some previous studies may be a difference in the contribution of red wine consumption to the total consumption of alcoholic beverages between populations.

In the present study, individuals in the highest category of red wine consumption declined less than those in lower categories. It should be noted that the median amount of red wine consumption in the highest category was 1·6 glasses per d. Since only a few individuals drank higher amounts of red wine in our population, we cannot extrapolate the linear beneficial association between low to moderate amounts of red wine consumption and higher amounts of red wine consumption.

Adjustments for several cardiovascular factors did not essentially change the observed associations. This might indicate that it is not alcohol itself that is responsible for a possible favourable effect on the change in cognitive function, since (moderate) alcohol consumption has favourable effects on cardiovascular risk, and cardiovascular risk factors have been associated with cognitive function and the risk of dementia(Reference Kivipelto, Helkala and Laakso38, Reference Duron and Hanon39). In addition, since we observed positive associations for red wine consumption and not for other types of alcoholic beverages and change in cognitive function, it is more likely that non-alcoholic substances in red wine (such as polyphenols) are responsible for a possible favourable effect on the change in cognitive function.

Future research should focus on substances in red wine that may be responsible for the association with slower cognitive decline. Results can be used in interventions to slow or prevent cognitive decline in order to postpone the development of dementia. Also, it has been shown that apoe4 carriers with higher alcohol consumption are more likely to develop the risk of dementia(Reference Anttila, Helkala and Viitanen8), and that daily wine consumption is associated with a lower risk of Alzheimer disease in apoe4 non-carriers only(Reference Luchsinger, Tang and Siddiqui19). The influence of apoe4 on associations presented in the present study is to be investigated.

In conclusion, moderate red wine consumption was associated with less decline in cognitive function in middle-aged men and women. We hypothesise that non-alcoholic substances in red wine may be responsible for any cognition-preserving effects.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the respondents and the epidemiologists and fieldworkers of the Municipal Health Service in Doetinchem for their contribution to the data collection for the present study. W. M. M. V was the principal investigator. The authors acknowledge J. Steenbrink and P. Vissink for providing logistic management, and E. P. van der Wolf for administrative support. The authors also acknowledge A. Blokstra, A. W. D. van Kessel and P. E. Steinberger for data management.

The present study was financially supported with a grant from the Internationale Stichting Alzheimer Onderzoek (grant no. 08 511). The DCS was financially supported by the Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sport of The Netherlands and the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. The data up to and including 1997, including the dietary assessment method, were additionally financially supported by the Europe Against Cancer programme of the European Commission (DG SANCO). H. B. B.-d.-M. was supported by the European Commission: Public Health and Consumer Protection Directorate 1993–2004 and the Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sport of The Netherlands.

None of the funders had a role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

The authors' contributions are as follows: A. C. J. N. and W. M. M. V. designed the research; A. C. J. N. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript; W. M. M. V. supervised the data collection, analyses and the preparation of the manuscript; H. B. B.-d.-M. supervised the development of the dietary assessment method and co-supervised the dietary data collection; A. C. J. N. had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors were involved in interpreting the findings, reviewed the drafts of the paper, and read and approved the final manuscript.

None of the authors had a conflict of interest.