Perhaps more so than any other area of music history, fourteenth-century France offers the sharpest contrast between a small number of sources transmitting music anonymously and the multiple, rich and probably complete manuscript collections dedicated to a single author: Guillaume de Machaut. We owe much to Machaut's decision to collect his own works into professionally executed presentation manuscripts.Footnote 1 Without these collections, our knowledge of his musical capabilities would be negligible and our understanding of wider chronology and stylistic development much poorer.Footnote 2 While some of his literary reputation would have remained, seminal works such as Le Livre dou Voir dit and La Prise d’Alexandre would not have come down to us. Without such works, we would have a poorer understanding of other authors’ inspirations, creative practices and cultural influence.Footnote 3 The standing of artists such as the ‘Master of the Remède de Fortune’ and ‘Master of the Bible of Jean de Sy’ would undoubtedly have remained high due to their contributions to other books, but the appreciation of the links between them and perhaps even of the quality of their overall output may have been diminished.Footnote 4 From the medieval point of view as well, it seems clear that the physical book played an important part in establishing Machaut's works as cultural capital worthy of collection by both the highest aristocracy and the courtier class.Footnote 5 Thus, any adjustment in the dating of these sources or in the narratives that surround their creation has wide resonanance, both in modern scholarship and in the way we understand our creative past.

This article concentrates on one of these books, namely, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, f. fr. 1586 (hereafter C). It discusses a missing element in current narratives surrounding this manuscript's creation, that is, the role, formation and use of exemplars.Footnote 6 The position of MS C as Machaut's first attempt at creating a ‘complete works’ manuscript is by now well established.Footnote 7 My interest here is in the circumstances and the process of bringing such a ‘first’ into being: the practicalities involved in carrying out such a project as well as the social reasoning behind it. Recent decades have seen a step-change in our understanding of the kind of professional, Parisian book-production process with which this source is associated.Footnote 8 Still, there are multiple lacunae in Machaut's biography during the 1330s and 1340s and none of his exemplar materials, records or receipts survives.Footnote 9 Making assertions about practicalities and reasoning involves dealing with motives and with the myriad accidents and coincidences of daily life. This is inherently speculative. Still, we know the book was ordered and delivered, that exemplars existed, and that they were a central tool in the operation of the professional Parisian book trade. Ignoring their influence on the book-production process serves only to obscure the limiting factors involved in such undertakings, not to compensate for or resolve their loss. Thus, speculation based on known processes is more likely to yield interesting insights than speculation devoid of context. In this contribution, I will endeavour to suggest a reconstruction of these materials as they pertain to MS C and to assess the insights gained from looking at this level of production.

I begin with an examination of our characterisation of patronage, authorial control and the practices through which workshops engaged with external entities, especially in relation to the creations of exemplars and their use. Two commissioning models will be considered – one centred on the patron, the other on the author – with the likelihood and implications of each assessed against our knowledge of Machaut's biography and against the general characteristics of MS C. Opting for the model of author as commissioner, the discussion moves to a close examination of the contents of this source and how they relate to decisions made during copying and illumination. Special attention is given to irregularities and difficulties apparent in this process, as these points are most likely to attest to the state of the exemplars from which scribes worked. I suggest that these anomalies can be explained as a result of the copying process itself, without recourse to external influences and coincidences. This shift, in turn, calls for adjustments in the narratives we construct around this manuscript's history. Finally, these various strands are brought together to form an alternative narrative for MS C's creation, assessing its implication for the ways we understand Machaut's social and creative practices, and with that, for wider generic development.

Were this narrative to be accepted, it would go beyond enhancing our concept of the process of creating manuscripts: it would call for changes to our understanding of author–patron relationships as they manifest themselves through artefacts; it would reopen questions pertaining to authorial involvement, control and the meaning of order in manuscript collections; it would redate the emergence of some compositional practices – most notably proposing that Machaut had begun setting rondeaux to polyphony and had used three-part textures in vernacular song composition before 1350 – and it would revisit the evaluation of differences between multiple copies of equivalent materials. While Machaut's case is unique, his central position in assessing wider practice in fourteenth-century France enables such outcomes to have broader reverberations. The key contribution that musical copying brings to this discussion should serve to bring musicological, codicological and literary analysis closer together.

First, however, it is necessary to present the currently accepted narrative surrounding this source.

MS C AND THE PLAGUE: CURRENT HYPOTHESES

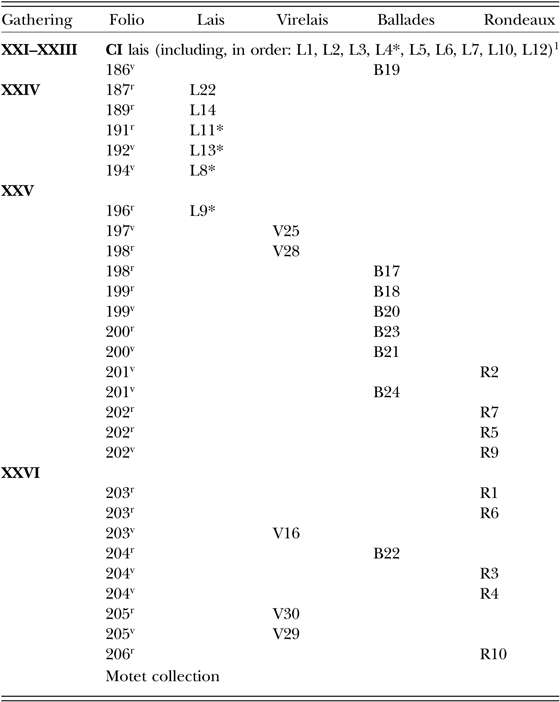

It is hard for anyone looking at MS C not to marvel at its beauty and richness.Footnote 10 Still, a closer look suggests that something did not go to plan during its creation. Towards the end of the collection a set of generically-mixed lyrics set to music has been copied in what seems a hasty and rather ill-fitting manner.Footnote 11 Furthermore, a brief codicological inspection reveals that the first 120 folios of the manuscript follow a clear practice of deviating from the use of quaternions at the end of each narrative unit in order to match poetic and structural units (see Table 1).Footnote 12 The pattern changes in its remaining 105 folios, with the lyric poems exceeding the gathering structure seemingly pre-prepared to house them and the generic units of the musical section being copied through continuously with no reference to the manuscript's physical structure. The adjustments to gatherings XVIII and XXVI suggest that this was not due to an early and consistent decision to change copying procedure at this point.

Table 1 Division of labour in MS C

Source: The table is based on Earp, ‘Scribal Practice’, pp. 371–3 and Guide to Research, pp. 77–9, 132–3. Similar expositions can be found also in Leo, ‘Authorial Presence’, pp. 287–8 and Leach, ‘Machaut’s First Single-Author Compilation’, pp. 254–5.

1 Unless a different number of bifolia is specified, all fascicles are quaternions.

2 Letters appearing in parentheses (gatherings IX, X and XIII) denote the still visible traces of a competing signature-system.

3 Scribe A: c. 15 quaternions, just under eight of which in music section (less text); Scribe B: c. 13.5 quaternions, two of which in music section.

4 1st assistant: 33 illuminations (2 oversized) in five gatherings (regardless of size); MRF: 34 illuminations (5 oversized) in five gatherings (regardless of size); MCB: 40 illuminations (2 oversized) in 11 gatherings (regardless of size/intensity).

I will discuss these characteristics in detail below. For the moment, it will suffice to say that they have been taken to represent evidence of a break in this manuscript's copying process: one which requires external, patron-focused narration. The accepted context for these presumed occurrences closely associate MS C with Bonne of Luxembourg (1315–49), Duchess of Normandy and wife of John (from 1350 King John II of France), who, it is claimed, may have had a hand in the original commissioning.Footnote 13 As a royal commission, the irregularities in the manuscript's structure are explained as a result of Bonne's untimely death. This separates a CI layer (fols. 1–186, and perhaps also fols. 211–25), designed to appeal specifically to Bonne and copied before September 1349, from a much smaller CII layer (fols. 187–210) added later, in time for a completion date before 1356. This divide assumes a neat terminus ante quem and terminus post quem for the contents of the two sections. For example, as all the rondeaux set to music in this source appear in CII, it is currently assumed Machaut first began interacting musically with this form in the early 1350s.Footnote 14 The apparent lack of organisation in the supposed post-Bonne additions is taken to evince Machaut's lack of involvement in the final stage of the work. Perhaps surprisingly, no specific patron-based explanation has been forthcoming for the decision to complete the manuscript in the early 1350s, or for the gap between it and Bonne's death. There is no consensus as to who funded MS C's completion, the exact state it was in when work ceased, or the origins of the added material.Footnote 15

At this point, it is worth stating that considerable lacunae exist in Machaut's biography, and that patronage can range from long-standing and consistent provision of professional services to a single, indirect point of contact. Other than his close association with John of Luxembourg up to perhaps the early 1330s and more settled residency in Reims from the mid-1350s onwards, we have no archival evidence for Machaut establishing exclusive, long-standing relationships with any known patron.Footnote 16 He certainly dedicated works to individual patrons and had dealings with others; the recurrence of such evidence suggests closer relationships, but this remains speculative. For example, the dedication of his Jugement du roi du Navarre (c. 1349) and Confort d’ami (c. 1357) to Charles of Navarre, together with the survival of a document referring to a gift of a horse from Charles to Machaut in 1361, testify to a long-standing relationship. Still, in itself, such evidence does not necessitate a decade of close proximity and continuous contact between the two men. Works can be dedicated from afar and may indicate initial contact rather than an established relationship. The situation with Bonne is even more precarious as Machaut only refers to her specifically in his Prise d’Alexandrie, written some twenty years after her death, and no archival documentation linking them survives. Thus, scholars who identify her as the dedicatee of the Remède de Fortune, of the supposed first conceptualisation of the Navarre, and as the moving force behind Machaut's monophonic virelais, consider her to be a major patron of the utmost importance while relying on problematic evidence.Footnote 17 Simultaneously, scholars with other interests can claim that ‘the traces of Machaut's association with [Bonne] are so slender and insubstantial that no such hypothesis appears very credible, at least on the evidence currently available’.Footnote 18

In what follows, I do suggest that Machaut's circumstances in the mid-1340s would have led him to consider Bonne as an obvious potential patron. This, however, does not imply such a relationship necessarily materialised. While some of my concluding remarks suggest that official acceptance of service may have occurred before Bonne's death, this is not central to my analysis for a simple reason: neither author nor patron exists independently of a practical context. The story, therefore, cannot only be about them.

As we have seen, the accepted narrative surrounding MS C is primarily patron-focused, at times also incorporating the author's wishes, but for the most part avoiding the practicalities of the book-producing workshop. The considerable amount of excellent codicological analysis based on it has thus been aimed at dating the copying work, or at identifying in the final product traces of Machaut's or of his patrons’ momentary wishes and needs.Footnote 19 Middlemen (and perhaps women) and the preparatory work their involvement necessitated of the commissioner rarely feature. Close interrogation of this stance raises a number of other inconsistencies. Assessing those requires a closer codicological look at the manuscript, but not before some clearer definitions are offered for the author–patron relationship and for the way each of them interacted with book-producers and their representatives. This is where we turn next.

ACTORS, ACTIONS AND ARRANGEMENTS: LAYING THE GROUNDWORK

It is becoming increasingly clear that some of the modern shorthand terms describing the process of manuscript creation are rather problematic in practice. John Lowden, for example, exposes the fluidity behind terms such as ‘patron’, ‘workshop’ and ‘iconographer’, even in cases where a manuscript's commissioning history is relatively well documented.Footnote 20 We know that a number of the artists engaged in the illumination of MS C cooperated elsewhere, and, as a group, they have been associated with service to the royal household in Paris.Footnote 21 Still, my use of the term ‘workshop’ is both wider and less institutional than these facts may suggest. I take it to refer to the non-binding or necessarily geographically and temporally concurrent assemblage of professionals charged with executing any element of a manuscript as distinct from author, patron or owner. For convenience's sake (and following the likely procedure in actual circumstance), it is imagined that the interaction with this vague grouping was funnelled through a representative subcontractor associated with the term libraire.Footnote 22

The level of execution, materials used, division of labour and quality of miniatures in MS C suggest a highly professionalised workshop.Footnote 23 Choosing such an entity to create one's manuscript had distinctive advantages, but also some specific practical implications. As is well documented, manuscript creation was a long and arduous process, often requiring a number of years from start to finish.Footnote 24 Indeed, the rationale behind organising professional workshops such as the one that produced MS C – with their established procurement arrangements and stable, efficient and specialised workforce working simultaneously – was to reduce the production period with minimal loss of quality.Footnote 25 Such multi-actor arrangements required a contractual basis and their smooth operation relied on clarity of plans and materials. A workshop could thus legitimately place certain demands on any prospective commissioner of manuscripts.

Initial negotiations would have involved the libraire assessing the timescale and price of the work envisaged. For this, he or she required an overview of the contents of the project and preferably its order. Non-textual elements would be particularly important. Historiation and illumination required the greatest investment of time and resources: illuminating a ten-line-high miniature clearly involved more expensive materials and would have taken longer to execute than copying ten lines of text. Illumination also meant disassembling copied gatherings and allowing for paint to dry before reassembling them.Footnote 26 Music created particular challenges in terms of layout and required specialist scribes.Footnote 27 Other essential parameters included the size of the intended manuscript, its writing block and the quality of its materials and visual programme.Footnote 28 In practice, the more unusual the copied materials (in terms of contents, specific programming and arrangement), the greater the importance of clear and well-ordered exemplars becomes. Late adjustments to the plan were possible and exemplars could be sent in tranches, but this would have cost and time implications, making it harder for the libraire to plan ahead or to orchestrate simultaneous copying and illumination. It could also potentially spoil the appearance of the manuscript or lead to some materials being copied a second time.Footnote 29 All in all, this was best avoided, though it undoubtedly occurred at times.

Due to the need to make sure that the workshop obtained all the materials it needed and knew how to reproduce them correctly, a commissioner's involvement was most intense at the beginning of the process. The multiple technical challenges offered by MS C made such involvement essential, though authors commissioning first presentation copies of their own work necessarily constitute the most extreme cases of such involvement.Footnote 30 Once decisions were made and exemplars supplied, the commissioner's role diminished. Their opinion may have been sought whenever problems arose, or they may have wished to interfere with the process in order to expand, delay or hasten it along,Footnote 31 but aside from funding payments they were no longer essential to the workshop's activities and the two entities did not have to maintain direct, regular contact.

In discussing the notion of ‘commissioner’, it is worthwhile separating it from both ‘patron’ and ‘author’. It is clear that in some circumstances it is possible to conflate two or three of these terms. Still, each carries a distinctive role within the creation process. With the ‘author’ role I associate the responsibility for providing the materials to be reproduced: the contents of the book. Clearly, the actual author of the works contained in any manuscript can be entirely absent.Footnote 32 Still, within the professional workshop's set-up, it is not the scribe's responsibility to choose and order the works to be copied. He or she requires an external ‘author’, be that a literal one, a compiling superior in the project's hierarchy, or an external provider of content. The ‘patron’ denotes the perceived recipient of the finished object, and, most likely, its eventual funder. Clearly, some presentation manuscripts have been created ‘in expectation’ of patronage before a specific recipient was chosen, or they have been created in such a way as to appeal to multiple potential recipients.Footnote 33 In such cases a degree of financial risk is taken by an intermediary, identified as the ‘commissioner’. In this sense, the ‘commissioner’ is the person on the ground who is involved in negotiating with the libraire, specifying decisions and delivering the exemplar materials. It is clear that a commissioner can also act (in whole or in part) as both author and patron, be associated with one or the other function, or exist independently as entrepreneur or agent. When entrepreneurialism is concerned, the commissioner can also double as a workshop professional. Clearly, lines can easily be blurred. As far as the workshop is concerned, for example, the creation of a book containing an original work destined for the patron who commissioned its composition translates into an author-commission: it is he or she who will be responsible for providing the materials to be copied, decide on the format of the book and come up with its visual programme, even if these actions are undertaken under time or financial constraints imposed by the copied work's patron. Patronising a work of literature is not the same thing as patronising its manuscript copy.Footnote 34 In such circumstances, the difference between the patron-commissioner and author-commissioner model relates mostly to whether decisions are dictated by a manuscript's eventual recipient, or whether they more cautiously rely on a pre-emption of the elements patrons are likely to find appealing. But how does this relate to MS C?

HIS BOOK – HER BOOK: PATRONAGE AND CAREER PLANNING

The patron–commissioner model as it is currently narrated raises many practical questions regarding MS C's process of creation: Why was it commissioned? Why then? If indeed a break occurred and Machaut had no involvement with its completion, why would he have allowed a project in which he seems to have invested so much slip out of his control? From where and how did the late materials arrive at the workshop? Was the final decision concerning the manuscript's contents and ordering more likely to have been taken by a particularly involved (though not the original) patron, or by the workshop producing the source? If Machaut designated an original order, was it followed? If not, why? If it was completed as a memorial to Bonne by her widower or orphan (the Dauphin Charles has been suggested),Footnote 35 why were the works in this source arranged so as to privilege her father? What triggered the decision to complete the source in the first place? What would have caused a patron to demand the presumed speed in which the work was completed (a characteristic used to explain the oddities of presentation in the CII additions)? After all, the need for the manuscript to be finished by 1356 so that John II could take it to England during his captivity and expose Chaucer to its contents could not have been foreseen.Footnote 36

The author-commissioning model also raises a number of questions. Some – such as ‘why?’ and ‘why then?’ – are very similar. Others, such as affordability, remain in the realm of patronage. Beyond this, however, they begin to diverge. As continuous authorial involvement and direct contact with the workshop can be taken for granted, the irregularities and inconsistencies within the manuscript have to be explained as a result of the creation process itself, rather than any external intervention.

Answering both sets of questions requires a degree of speculation and while logical, well-founded explanations offer consolation to scholars, experience teaches us that this seldom happens. As we are dealing with creative decisions and luxury objects, some emotive and ephemeral decision-taking is to be expected. We have seen that in practice, the two models may not be as far removed from one another as one might first expect. It is hard to imagine Machaut not acting as the commissioner, regardless of whether he fulfilled that role at the behest of a specific patron's order or undertook the project of his own accord, expecting to find a patron at a later point. Still, in what follows I attempt to demonstrate that a shift away from the patron and towards practicalities defuses certain questions and helps answer others, placing us on a more secure methodological and logical footing when reconstructing this manuscript's early history.

I would argue that the contextual and physical characteristics of MS C do not support a mere agent role for its content's author. As his first collection, Machaut must have been the source for some if not all of the materials to be included, probably forcing upon him some intensive preparation work beyond simply handing over his personal archive.Footnote 37 While single works undoubtedly circulated independently, collecting and collating as many of them as possible (keeping in mind that they were written for different patrons at different times and places) would probably not result in what retrospectively seems a complete collection.Footnote 38 Furthermore, MS C contains newly codified generic structures, the latest in music notational techniques, an intimate relationship between both text and music and between these and the illumination programme.Footnote 39 All this would have required an intensive initial contact between libraire and commissioner and, preferably, the provision of particularly good exemplars.

MS C does not present any obvious signs of specific, aristocratic commission: it sports no dedication, presentation portrait, motto or coat of arms in its presentation. All the same, in other contexts such characteristics have been taken to suggest royal intimacy rather than distance.Footnote 40 Our understanding of the patronage of this source relies on a combination of the careers of the artists who worked on it and the arrangement of the works it contains. Even when set up, the poet–patron relationship seems expectative rather than pre-ordained: the book does not show signs of being externally commissioned by a patron, but rather of an expectation it would find a willing audience ready to celebrate (and compensate) the poet for his efforts once presented with the finished artefact.

In case the funding of such a project should be deemed beyond the means of a cleric in Machaut's situation, one should note that an author-commissioner could have ended his or her involvement with a manuscript before any prohibitively expensive illumination took place. In order to ensure the correct ruling and layout for the text and music – letalone estimate the price of the project as a whole – the illumination programme had to be agreed early on in the production process, probably as part of the initial negotiations. Instructions to the artists could have been kept by the libraire for a long while, separating the copying from the illumination bill, the latter being potentially settled by a later patron.Footnote 41 Even without this proviso, Machaut's inability to afford such an investment is not beyond challenge. Our best price comparison is the manuscript Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, f. fr. 167, a copy of the Bible moralisée made for King John II of France in the early 1350s and illuminated by some of the same artists who worked on MS C.Footnote 42 The cost of its illuminations amounted to some 320 livres at a rate of about 1 livre per working day: well beyond Machaut's means. This task, however, involved executing 5,112 illuminations as compared to MS C's 107. The pigments, gold leaf and occasional larger illuminations of MS C surely made it more expensive per image than the grisaille of the Bible moralisée, and both cases would have involved many additional costs such as buying parchment, ink, copying and binding. Nonetheless, a proportionate reduction in the expense of illumination suggests that such an undertaking may have been within the scope of a cleric enjoying a stable annual income totalling 100 livres.Footnote 43 Even if we assume that each of MS C's illuminations were three times dearer than their Bible moralisée counterparts, the total price of this element of the production would still amount to around 20 livres. A substantial investment, but not unmanageable.

Let us now consider Machaut's situation at the point of commissioning his first collected-works manuscript. The dating of the illuminations, the dits it contains and the time it would have taken to create such a manuscript combine to suggest that the decision to commit the necessary time and capital was probably taken in the second half of the 1340s.Footnote 44 Machaut would have been in his mid-forties. He was clearly an established musical and literary figure with links to the ruling dynasties of France and Bohemia, and enjoyed a secure income from two prestigious benefices.Footnote 45 This was, nevertheless, a period of instability in Machaut's artistic career, following the loss in 1346 of his most important, long-standing and intimate patron, John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia. Furthermore, up to this point considerable portions of his adult life had been spent travelling with John's court. As a result, it may well be that many of his works did not circulate in his home country and that his personal relationships with the wider French nobility were perhaps not as strong as he would have liked them to be. Roger Bowers has suggested that regardless of Machaut's whereabouts in the decade before John's death, he remained officially affiliated with the King of Bohemia until ‘upon the dissolution of his [John of Luxembourg's] household Machaut would have needed to find alternative work with some other employer. Certainly it appears that at this juncture he did not resort to the role of a canon residentiary of Reims.’Footnote 46 He may well have moved away from John's inner circle a good number of years earlier, and was – according to Lawrence Earp but contrary to Bowers's opinion – perhaps more or less permanently attached to Bonne's court by this point.Footnote 47 If the Remède was indeed written for her, a link of some kind must have existed: it is not too fanciful a notion considering Machaut's services to her father and the links between the Luxembourgs and the Valois. They already belonged to an established network, in which cultural artefacts played a part. Nevertheless, we have seen that the surviving documents from this period link Machaut with John's and no other specific patron's business. At least officially, he seems to have remained ‘John's man’ until the king's death, even if from a distance. If this was the case, he would have needed to attach himself to a new court in a more official capacity at this point in his career, be that with Bonne and John of Normandy, as Earp suggests, or with Charles of Navarre, as Bowers proposes. The associations of single works cannot be seen as decisive evidence here, as they could have been written while in John of Luxembourg's service. Still, as the proposed dedicatees of his earlier large-scale narratives point towards Bonne (Remède) and her eldest son or court (l’Alérion), this would have been a reasonable first port of call when looking to establish a new, official allegiance. I tend to support this association from the point of view of Machaut's likely prospects at a given point of time and set of circumstances, regardless of whether it materialised. Seeing the book as a means to acquire patronage makes sense of the object, regardless of the result once finished, and its lack of stated affiliation echoes this function. Yet many questions remain, not least the possibility that the same function relates to a different point in Machaut's career.Footnote 48

Why should Machaut have chosen this precise moment to take upon himself the complicated and costly project of collecting his complete works in a sumptuous presentation collection? There are, of course, any number of possible explanations. For example, Earp suggested as one such reason a heightened sense of mortality in the face of the ravages of the Black Death.Footnote 49 To my eyes, however, the most likely option would be the potential use of such an artefact in cementing a new patronage relationship. A certain amount of hubris can perhaps be pinned to a decision to create a complete-works manuscript rather than a presentation copy of a single work, especially as Machaut would have been hard-pressed to find a model for this kind of commission.Footnote 50 Furthermore, the Remède de Fortune, with its musical interpolations and didactic structure, would have been ideal for such a purpose.Footnote 51 As Froissart's reading of his Méliador to the Count of Foix makes clear, works such as the Remède could have been used in this capacity regardless of their original dedicatee.Footnote 52 Still, one can assume Bonne already had access to a good number of Machaut's works, including the Remède.Footnote 53 If she was first on the list of potential new patrons, the Remède alone would not do as an introduction to his abilities. More generally, his previous professional position in Bohemia, away from the Francophone heartlands, may have caused him to believe that a fuller résumé of the extent and versatility of his abilities would help his search for a new patron, especially if Bonne were not to prove forthcoming.Footnote 54

Thinking along these lines, it would have been a pity not to be able to demonstrate both the impressive bulk and the variety of his work. After all, any dedicatee interested in cultural production would have appreciated his specific achievements in narrative-writing inspired by the Roman de la rose, as well as the special case of the Remède and his cutting-edge preoccupation with both lyrical and musical fixed forms. In this scenario, speed would have been important but not the only objective. After all, Machaut already had links with powerful potential new patrons as well as an independent, stable income. More importantly, such a decision would have required him to have organised his works into at least rough, initial exemplars. Had he not done so, meaningful negotiations with a libraire would have been impossible. Apart from preparing his exemplars, Machaut would also have had to raise funds to get the manuscript project started. As the choice of workshop attests, quality was paramount.

Up to this point, my imagined contextualisation tallies well with the accepted narrative of the creation of MS C. The two differ only in the book's potential to establish a patronage relationship rather than to celebrate one and in drawing attention to Machaut's need to create exemplars and negotiate with the workshop as first steps in the creation process. While the affiliation with an author-commissioner model rather than a patron-led process weakens the notion that Machaut was not involved in the source's completion, it will only become compelling as an alternative narrative if the specifics of the manuscript's structure can be accommodated at least as convincingly without external input.

THE DITS: BETWEEN ORDER AND GATHERING STRUCTURE

The narrative dits that open MS C are each carefully copied onto separate sets of gatherings.Footnote 55 This arrangement was taken to indicate Machaut's wish to be able to change their order until the very last moment, with the final decision having been designed to appeal to Bonne of Luxembourg, or revised (perhaps by her son Charles) after her death.Footnote 56 While the physical analysis is beyond question, its implications are not. The most basic problem is that of intentionality: does the fact that the copying technique allowed for last-minute changes mean Machaut intended to exploit this flexibility, or did he have an order in mind regardless of the gathering structure, it being the result of workshop practicalities? If order was an ongoing artistic preoccupation,Footnote 57 he could have specified it while deciding on the number, position and contents of MS C's illuminations, perhaps in the form of an overall list.Footnote 58 If he did not specify an order at the beginning of the process of creation, could it be that he invested so much in the visual presentation of this source but did not care about the order in which items were to be placed? Did he need extra time? How would more time enable him to improve the order? Was it because he was not sure which order would most appeal to Bonne, or because he hadn’t yet settled on the book's final recipient? As the implicit or suggested patrons for all five dits to appear in this collection are Bonne's immediate family,Footnote 59 could he have gone wrong? Would it have been possible to order this group of works in such a way as to avoid the appearance that it was made for her or for a member of her immediate family? If Machaut was not sure who this manuscript was for, should we not try to come up with an explanation other than the link with Bonne as to why he commissioned it in the first place?

Before attempting to answer some of these questions, another relevant physical characteristic should be taken into account. When looking at the five dits MS C contains, the Behaingne – which opens the manuscript – is the least sumptuously presented of the lot. Its image-per-folio ratio is the lowest and the illuminations were not executed by the best artists available.Footnote 60 More often, it is the beginning of a collection that is given the most visual attention, as this would be the first locus of engagement between it and the prospective patron-reader.Footnote 61 If this work was given the least amount of visual attention, why was it placed first? Why would Machaut decide on an overall illumination programme that attracts attention away from it rather than towards it? The ‘calling card’ attitude presented above may offer an explanation. Placing the Behaingne first can be read as creating familiarity, this being the most famous and widely distributed of Machaut's dits. By playing on existing associations, the reader is drawn in, raising the likelihood he or she will go on to examine the other works on offer. The enhanced presentation of the other works then draws the reader further in. The Remède, placed directly after the Behaingne, is the most effective in this regard. It looks more like a manuscript opener: it presents the highest level of artistic ability and execution in the whole collection, occupies the most space of all the dits present, and has the extra interest of the integrated music.Footnote 62 After being drawn in, one cannot fail to be impressed.Footnote 63 The concentration on Machaut's needs rather than those of a commissioning patron goes some way to explain the lack of specificity here: the association of single works with patrons concern the literary content, not the object of the book. The texts’ association with the Luxembourg dynasty was unavoidable, though this in itself would not have reduced the appeal of the collection to other potential patrons.Footnote 64 It would have made sense, however, to attract their attention by means beyond kinship. The non-specificity of the book itself left options open to the author-commissioner in case things did not work out with the most likely new patron (Bonne) or some other opportunity came up (as perhaps was the case with Charles of Navarre). It may even be that it was deemed inappropriate to visually specify a patron without their direct commissioning or prior acceptance of the project.Footnote 65

Table 1 demonstrates that not only were dits copied on separable gathering-structures, but that each such physical and literary unit was illuminated by a single artist. A common explanation for this is that it allowed the artists greater control in creating and executing the programme of illumination.Footnote 66 I contend that such assertions are only relevant in terms of the consistency of the visual presentation within each work. After all, the planning of the programme would have taken place between the commissioner and libraire long before the scribes or artists got involved. Scribes, in turn, fixed the location and size of the illuminations through the amount of space left empty for their execution. Finally, illuminations were executed following either sketches, verbal descriptions or reference to external lists of images or instructions.Footnote 67 Furthermore, due to the practicalities of drying, artists regularly dismantled gatherings and illuminated loose bifolia.Footnote 68 Put together, this process would have obscured the text's narrative flow and resulted in non-consecutive illumination, making it unlikely that an artist had much interaction with the text illustrated. Evidence from other Machaut sources raises further questions about this link. MS E often matches work and gathering structure, even though all but its first two illuminations were executed by a single artist.Footnote 69 The through-copied Vg, on the other hand, includes gatherings from a single work that were divided between a number of artists.Footnote 70 While the latter practice may not be ideal, it seems that as long as no marked stylistic changes got in the way of enjoying an illumination programme as a whole, commissioners, workshops and, by implication, readers accepted multi-artist collaboration within single narratives.

Another technical element that can, at times, be misconstrued is the meaning of gathering signatures. This is particularly pertinent for MS C as evidence remains of two different signature systems (see Table 1 above). Signatures are often associated with the very last element of production, that is, a manuscript's binding. It is of course true that a binder would require instructions for ordering gatherings (without engaging with their contents), as well as a mechanism through which to ensure each gathering was internally consistent.Footnote 71 Still, the need to keep track of the materials and to be able to take apart and rearrange sets of gatherings would have been required much earlier in the process. As already mentioned, artists illuminating one bifolio at a time would have had to do just that and would have required a system for reassembling and putting gatherings back in order once the paint had dried. The second set of signatures appearing on gatherings IX to XIII, for example, does not necessarily indicate that the Alérion and Vergier were at one point intended to begin the collection, only to be relegated to the end of the dits section. It more likely refers to the internal structure of the bunch of gatherings sent to the ‘Master of the Coronation Book of Charles V’ for illumination, perhaps even added by him/her before dismembering them.

Why, then, copy dits into independent structures? I contend that the best reason for doing so would be that this represents the state of the exemplars used. I do not suggest that the presentation in MS C is a faithful reproduction of the shape and size of the exemplars provided. Indeed, I would find it rather surprising for Machaut's personal copy to have included more than annotated suggestions for an illumination programme, thus saving much space. Furthermore, there is no easy way of reconstructing the size of his copies or how many lines and columns per page they contained. There is also no reason to believe that the various dits – written over a protracted period of time – were kept in the same format. I do not believe that Machaut would have had any practical alternative to keeping his personal copy of each work in some kind of rationalised and unified physical structure.Footnote 72 As rhymed verse results in the length and number of lines for each work being set, it would only require a straightforward calculation to transit from one layout to the other and to plan gatherings accordingly. Indeed, a change in layout would make it more practical for one scribe to copy an entire dit, as it would be harder to coordinate dividing up the copying work if old and new layouts did not match. As the Remède was to receive special treatment by scribe, flourisher and artist, it made sense to be able to maintain its structural integrity (and by implication, that of the other dits). This would have facilitated passing it around between the various practitioners, setting it apart from the manuscript's other materials. This practice would have been unavoidable if we imagine Machaut sending his works to the workshop in dribs and drabs rather than as a complete unit, but this does not seem likely.Footnote 73

Without imagining a long build-up to the commissioning of MS C, a situation ruled out by viewing it as a reaction to John of Luxembourg's death, preparing new exemplars for the five existing dits would have been time misspent. Viewing the commission as a more spontaneous or reactive act leaves no obvious, practical alternatives for Machaut other than to have sent the narrative work to the workshop in their existing, self-contained structures. This position is further supported by the mirroring of MS C's readings in the surviving single-work circulation, often deemed to be ‘early’.Footnote 74 Using such materials would have been a helpful starting point in negotiating the details of the commission, and would have enabled work to begin immediately while the more problematic exemplars for the shorter works were being prepared. The workshop, in turn, would have had no practical or technical reason not to follow this arrangement.Footnote 75 After all, it made life easier, both in terms of the division of labour and in maintaining uniformity of visual presentation. While the ability to tweak the final manuscript order later on may have been an added bonus, I suggest this would not have been the driving force behind opting for the gathering structure visible in this manuscript.

THE PROBLEMS BEGIN: COPYING THE LOANGE

The structure of Machaut's personal collection of shorter lyrics is harder to gauge. While the imagined act of composition depicted in the miniature that opens this section of MS C shows the author surrounded by various unordered scrolls of parchment (fol. 121r), the non-musical lyrics (usually referred to as the Loange des Dames following the rubric introducing them in MS F-G) may already have been kept in a booklet. After all, writing down the shorter works required little space, making a one-per-sheet storage technique rather chaotic and involving scraps of various sizes. Unlike copying music, poetry requires no special design, ruling or preparation, and can be copied in succession without creating layout difficulties. The large number of poems – 198 in MS C, over twice the number of musical works – would have called for some kind of organisation. As their composition appears more or less continuous, a gradual addition to a pre-prepared set of gatherings seems a reasonable assumption.Footnote 76 As a personal archive, these materials may still have presented the poetry in a suboptimal arrangement. If, for example, efficiency and economy of space were prime considerations, single-column ruling of as large a writing block as possible may have been employed. This would imply that the poetry was copied in a prose-like fashion rather than being lineated. This technique was familiar to Machaut: the residual texts of his ballades and rondeaux employ it consistently in all his later manuscripts. In any event, in preparing materials for the workshop, the creation of some kind of structure was likely, as a large bundle of individual works on single sheets would have been badly received and would have increased the potential for error or omission. As with the music discussed below, the process of achieving ordered exemplars could have taken place before the official commission, allowing Machaut to have a better overview of his materials and thus negotiate the planning and execution of the source more efficiently. Alternatively, the ability to send the dits straight away in their pre-existing structure may have given Machaut time to create new exemplars for the shorter works at this point. This second option is perhaps more appealing, as it more easily accommodates the structural anomalies that begin to appear from this point on.

As already hinted, current understanding views this part of the manuscript as the point where the problems began. As with the dits, a separate, irregular gathering-structure was also prepared for the collection of lyrical poetry (gatherings XVI to XVIII), though unusually, the copying of this section was divided between the two text scribes. When it came to copying, this section overshot the prepared space by nearly two folia.Footnote 77 The expanded gathering XVIII (a quinternion) suggests a clear expectation existed for the space needed to copy the lyrics, most probably reliant on the form in which they arrived at the workshop. The division of labour may at first glance suggest that this section was copied by the two scribes simultaneously, but the copying of Hé! gentils cuers, me convient il morir (Lo37) over the seam between gatherings XVII and XVIII negates this, as well as the possibility that gathering XVIII was a late insertion.Footnote 78 It is possible to consider Il m’est avis qu’il n’est dons de Nature (Lo188) – which covers the seam between gatherings XVIII and XIX – and the lyrics that follow it as later additions, but as the scribal hand changes with the structural break and not the lyrical unit, this seems less likely.

In all, I contend that the most likely scenario for this ‘overshoot’ was a mismatch between the layouts used in the exemplar and the manuscript copy. If Machaut's personal, un-lineated copy of the Loange was used as an exemplar, the libraire's difficulty in assessing the number of lines required for this section becomes more understandable. The addition of an opening illumination and scores of rubrics labelling genres may also have interfered with the workshop's planning. In practice, this was compounded by the difficulties of Scribe A in particular in deciphering lyrical structure: he often split poetic lines in two, strengthening the notion that the lineation in the exemplar was suboptimal.Footnote 79 As we have seen, the rationale for professionalism was the saving of time. Professional scribes would not have expected to have to engage deeply with the author's intentions or have to interpret the materials. Indeed, there was no guarantee they would have had the poetic knowledge to do so even if they had the will and time at their disposal. In total, these issues added 151 lines to the space required by this section, accounting for more than half the ‘overshoot’.Footnote 80 Had they been avoided, a single grafted folio would have sufficed to accommodate the estimation error. I find this hypothesis appealing as it combines a likely technique for lyrical archiving unrelated to the practicalities of manuscript-creation with a useful tool for explaining the structural anomalies in MS C as resulting from difficulties encountered by various workshop members.

At the point of this structural seam, a scribal decision had to be made. It was not obvious to decide to start a new quaternion as it would have been abundantly clear that the remaining Loange materials would not suffice to fill it. A different option would have been to copy the remaining materials on single sheets or on a bifolio, grafting them into the structure once the remaining Loange lyrics were copied. While this would have enabled the workshop to maintain a correlation between genre and structure, it was perhaps decided that grafting further materials onto the already extended gathering XVIII would make it too bulky and result in a visible anomaly once the various gatherings were sown together.Footnote 81 Furthermore, considering the estimation error involving the lyrics, the workshop may have been justified in worrying about the copying of the innovative and technically more challenging music section. Committing to grafting here may have forced multiple subsequent graftings at a later stage. This would not only make the production process more complicated, but could potentially diminish the overall look of the final product and thus dent the workshop's professional reputation. The decision to copy through thus seems reasonable on a number of levels, even though it sacrifices the ease with which division of labour can be organised. As a result, only one change of scribe occurs beyond this point. Its location at a generic point of transition in the middle of gathering XIX attests to consecutive, rather than simultaneous, copying here. The decision itself and change of scribal hand at this point suggests it was at least given some thought and was probably taken by a superior. This cumulative lack of confidence may have resulted in the subsequent adoption of the ruling practice suggested for the entire music section of MS C, whereby large-scale preplanning was forsaken in favour of ruling space for each work immediately before copying.Footnote 82

IT ALL GOES WRONG: THE MUSIC OF CI

Creating exemplars for MS C's music section would have posed a different set of challenges. Arguably, Machaut would have had no reason prior to this point to arrange his music into structured gatherings. While a substantial collection of nearly a hundred works would have called for some organising principle, I suggest this was more likely a separation into generically based bundles than gathered booklets. Such an internal division would have made the music easier to handle than an equivalent single stack of poems, the visual presentation of each genre – reliant on the internal repetitions unique to each one – simplifying differentiation between groups. Nevertheless, using a single pre-ruled layout for each genre would have been inefficient, indeed wasteful. Within each generic group, different lengths and complexities of both poetic and musical setting could require vastly different amounts of space for the various compositional elements. For example, the decision to set a ballade in two, three or four voices would have meant significant implications for the arrangement of the page, and in order to accommodate the latter, a reproduced layout would not be efficiently used in the former. Variability of intra-generic poetic structure would result in different amounts of space being required for each piece, voice and textual residuum, with these differences potentially amplified by changes in the setting technique. Thus, identically structured texts may have required completely different layouts when presented musically, according to the number of voices chosen and the length and frequency of melismas within them. Without the ability to reproduce a ruling pattern or to predict the layout, the appeal of using pre-prepared musical gatherings is greatly reduced.

As with the Loange, the workshop was likely to have placed at least minimal demands on the exemplar materials. This was perhaps even more important for the music, as current knowledge suggests that no precedent for the collection of Ars nova secular polyphony was available at the time.Footnote 83 In what follows I suggest that Machaut's ordering technique was to find a consistent process for organising old works into quaternion units for each genre, postponing contending with works that could not be fitted into such structures (either due to unusual layout, or simply because a quaternion was full) to a later date.

The first two generic groups to appear after the Loange – sets of virelais and ballades copied continuously without a correlation of genre and gathering structure – are structurally interesting nonetheless. As attested by the space they occupy in the manuscript (fols. 157v–165r), the sixteen ballades of CI would fit perfectly onto a quaternion, one on each of the sixteen sides this structure affords.Footnote 84 The twenty-three monophonic virelais that precede them required a little more space in the MS C copy (fols. 148v–157r), but considering a likely less expansive copying technique for their many residual strophes, I contend they too represent exactly a quaternion's worth of exemplar materials.Footnote 85 Indeed, the inclusion of twenty-three rather than twenty-four virelais here supports the quaternion hypothesis. While including twenty-four songs would have resulted in a mathematically pleasing ration of three songs per folio, translating this into a gathering structure would have resulted in a virelai being stretched over every single page turn. Copying only twenty-three works allowed for a single work to be copied onto the first recto and the last verso of the gathering, and three songs to be copied on each of the seven full openings this structure offers. This eliminates the page-turning problem.Footnote 86

All the virelais that appear in MS C are monophonic, and while the number and length of lines varies, their generally syllabic style of setting allows for a relatively straightforward estimation of the copying space they would require. Thus, when Machaut came to prepare exemplars for this genre, he would not have had difficulties in planning a ‘gathering's worth’. Perhaps he expected the workshop to continue the copying technique of the dit section, matching gathering structure to genre, but this did not happen in practice. I suggest that while it was the lyrical ‘overshoot’ that caused the subsequent mismatch between generic groupings and gathering structure, it was the technically ground-breaking elements of copying the musical materials that made the workshop weary of estimating the space required for each one. This is supported by the ad hoc ruling practice adopted for the music of this source mentioned above and explains the gap between the amount of space used in MS C and the proposed quaternion exemplar-gatherings from which it was copied.

BRIDGING THE SEAM: PLACING THE LAIS

The lais follow directly on from the virelais and ballades, also beginning mid-gathering (fol. 165r). Nonetheless, this generic unit stands out both structurally and visually. Structurally, the collection of lais stretches over the location presented above as the point of transition between CI and CII (fol. 186v, at the end of gathering XXIII, where a single ballade interrupts the generic collection).Footnote 87 Its beginning also marks the only place in the manuscript where a change of text-scribe occurs mid-gathering.Footnote 88 Visually, it is unique in the Machaut manuscripts in coupling an illumination with each song. Indeed, MS C contains no other illuminations in the entire music section. Thus, the miniature for L1 on fol. 165r is the first such insertion since the beginning of the Loange on fol. 121r, and the fifteen lai illuminations that follow are the last of the manuscript. The series has been interpreted as presenting an overarching, unifying narrative for this generic section, suggesting that they (rather than the songs themselves) had been conceived as a unit.Footnote 89 It seems that the lais were particularly important for the commissioner.Footnote 90 There is no evidence of an interruption within the illumination process of the lais. Thus, illumination either took place after an interruption between CI and CII, or the transition was smoother than hitherto proposed. This point is important, as it suggests that any changes of plan and structural adjustments took place within the original production process.

The ordering of this generic collection relies on the hypothesis that the exemplar used here mirrored the stable order of lais found in Machaut's later sources, but included the instruction to copy first the musical lais and move those not set to music to the end of the generic section.Footnote 91 Coupled with the visual programme, this scenario demands a clear set of instructions by the commissioner, as well as the workshop's deep engagement with the exemplar materials. While unusual in the context of MS C as a whole and of wider professional workshop practice, I concur with it here. The shape of the lai exemplars was never fully discussed. Still, the notion of a set order represented in a later collection but reworked here only works if it was physically evident. While a list commenting on chaotic materials could have sufficed, a gathered set of exemplars accompanied by instructions as to how to deviate from them makes more sense to me. Counting the non-musical works as well, which appear early on in the generic order in later manuscripts, I suggest the CI lais would have fitted on three exemplar quaternions.Footnote 92

The unusual copying procedure could go some way towards explaining the surprising position of the lais in this source (though I propose alternative explanations below). As with the visually rich Remède, one may well have expected the illuminated lais to open the music section.Footnote 93 As discussed in relation to the narrative work above, evidence of the early circulation of Machaut's lais supports an authorial, reader-focused explanation for not placing the most attractive and familiar works first.Footnote 94 Still, the same order of generic presentation could have transpired through the workshop deciding to tackle the technically unprecedented musical section of this source in order of increasing difficulty. First, the more usual materials were copied (dits, then poetry), followed by those music exemplars to be reproduced as supplied (first the easier to lay out, monophonic and text-rich virelais, followed by the polyphonic ballades), leaving lai exemplars, which required active interaction and reordering, to the end. The problems encountered in copying the Loange and the lack of confidence in pre-planning the music's layout resulted in the inability to reorder genres at a later stage.

The seam between CI and CII opens up three procedural possibilities, all of which create difficulties for the current narrative for the creation of the manuscript as a whole. One option, tentatively suggested by Earp, imagines the copying process of the CI materials to have been completed before the supposed break between the layers occurred.Footnote 95 As his understanding of this source necessitates the association of the motets with CI, Earp imagined an original gathering containing the text-only lais and first five and a half motets being discarded and its contents recopied after the decision to insert CII was made.Footnote 96 Consequently, this view sees the copying of this manuscript's text as having been completed by the time of Bonne's death in September 1349, presumably, however, at least partially unilluminated. This complicates the narrative concerning the transition between the two sections. As the process of illumination would have been time-consuming and not necessarily immediate, the notions of an abrupt downing of tools in reaction to Bonne's death or of a hasty completion at some later point are both weakened. Other questions also arise: if the source was so near completion, why wait? Why not turn it immediately into either a commemorative artefact of its originally intended recipient, or the facilitator for a new patronage relationship? The subsequent CII addition becomes entirely opportunistic, inserted to update the ‘completeness’ of the manuscript. The substantial effort required – the diminished visual presentation of the CII songs and the loss of the clear generic principle of organisation – are taken as a price worth paying for this, regardless of who was responsible for the decision. These problematic characteristics are also taken to evince haste in the execution of CII and the possibility of Machaut's detachment from the process, but while up-to-date completeness would perhaps be meaningful for Machaut, would it be for his readers? If he was not involved, how could anyone guarantee completeness? If completeness was so important, why was the Navarre not integrated into the dits section?Footnote 97 As illumination would take much longer than copying CII, why the rush? Why does CII not reflect more closely the visual qualities of CI? This version of events would also diminish the viability of the notion that a single narrative and visual programme stretched over the entire lai section, or at the very least, that the one currently on view was Machaut's original plan.

The second option is that the non-musical lais were not copied and then recopied, but were held back for copying later, making sense of the empty space on fol. 186v. This, however, would suggest that the downing of tools here was primarily a reaction to a problem in the supply of materials for copying. It imagines an expectation of a need to copy works not yet present before the manuscript could be considered complete. According to this view, at least elements of CII were part of the original manuscript plan – indeed, integral to its design – and Machaut continued his involvement in the project until its completion. To my eyes, the most likely materials for which waiting would have been worthwhile would be the final lais of the pre-envisaged series and an entirely missing generic collection; but I will return to the rondeaux below. The third option is closely related to the second, but relies not on an expectation of new materials, but on a division between materials of different quality: between clean and problematic exemplars. Here, the unusual copying of the Lay de plour (L22) – a work beginning on fol. 187r, and thus marking the beginning of CII – is perhaps telling. Earp suggested that the problematic yet workable truncated end of its music can be explained by imagining this copy relying on an exemplar akin to Machaut's ‘autograph’.Footnote 98 While he interprets this to claim L22 must have been a recent composition at the time of copying (i.e., closer to option 2), one can just as easily associate the difference with a transition from reliance on materials designed as exemplars for professional copying to personal copies destined for the author's archive (option 3).Footnote 99

Both options 2 and 3 transfer responsibility for the contents and presentation of CII to the original commissioner, and I find them practically simpler, generating fewer problematic implications. An awareness that the series of lais contains more works than were to be found in the CI exemplars would be another reason to place it after the virelais and ballades rather than at the head of the music section. The continuous copying technique adopted caused this to be the only location where a seamless transition between the layers would have been possible. Viewed in this light, workshop practicalities explain the surprises in this manuscript's structure. While neither option specifically contradicts coincidence with Bonne's death, neither requires it in order to make sense. Indeed, neither requires a break between the copying of the two layers.

If, as I propose, we opt for the second or third option and choose to eliminate the break between CI and CII, the questions raised in relation to the first option are defused and other implications arise. For example, understanding at least some CII materials as forming part of the original manuscript plan suggests that such compositions must have pre-dated the manuscript's commissioning, making them potentially as early as works copied into CI. Disassociating the two layers from notions of ‘early’ and ‘late’ has the potential to change our chronological understanding of both this manuscript's creation process and Machaut's creative activities. For example, the motets can still be considered pre-1349 compositions even if we imagine them being copied after, rather than before, the CII songs, and conversely, the composition of the rondeaux does not have to post-date that year due to their location within the manuscript. Moreover, the very necessity to use 1349 as a linchpin for dating is undermined. For all this to be viable, however, alternative interpretations must be found for the unique characteristics of the CII section. Elizabeth Eva Leach's assertion that the quality of scribal work did not diminish here makes it possible to infer that no change in attitude or working practices occurred at this point.Footnote 100 This implies that the differences seen in the manuscript are not the fault of the workshop, but of the materials supplied to it. The most straightforward way of explaining them is through a marked deterioration in the quality of the exemplar,Footnote 101 that is, a transition from relying on clearly copied gathered exemplars to working with Machaut's personal, unstructured versions. As this change is physical rather than temporal, it does not matter whether such materials arrived at the workshop late (option 2 above), or whether they were available in this form all along (option 3). Indeed, a combination of the two is also possible. Before assessing why this could have happened and how the workshop may have reacted, let us look at the orderly motet section, which up to now was considered part of the older layer of this manuscript.

ACCOMMODATING CII, RECOPYING MOTETS

MS C's motet collection did not seem to challenge the workshop, and it was probably copied from a set of structurally unified exemplars. After all, models for collections of motets were already available, and the simplicity and regularity of its one-work-per-opening layout left less room for error. The evidence of programmatic ordering suggests that the organising hand was that of the commissioner rather than the scribe. It was probably always intended to end the manuscript.Footnote 102

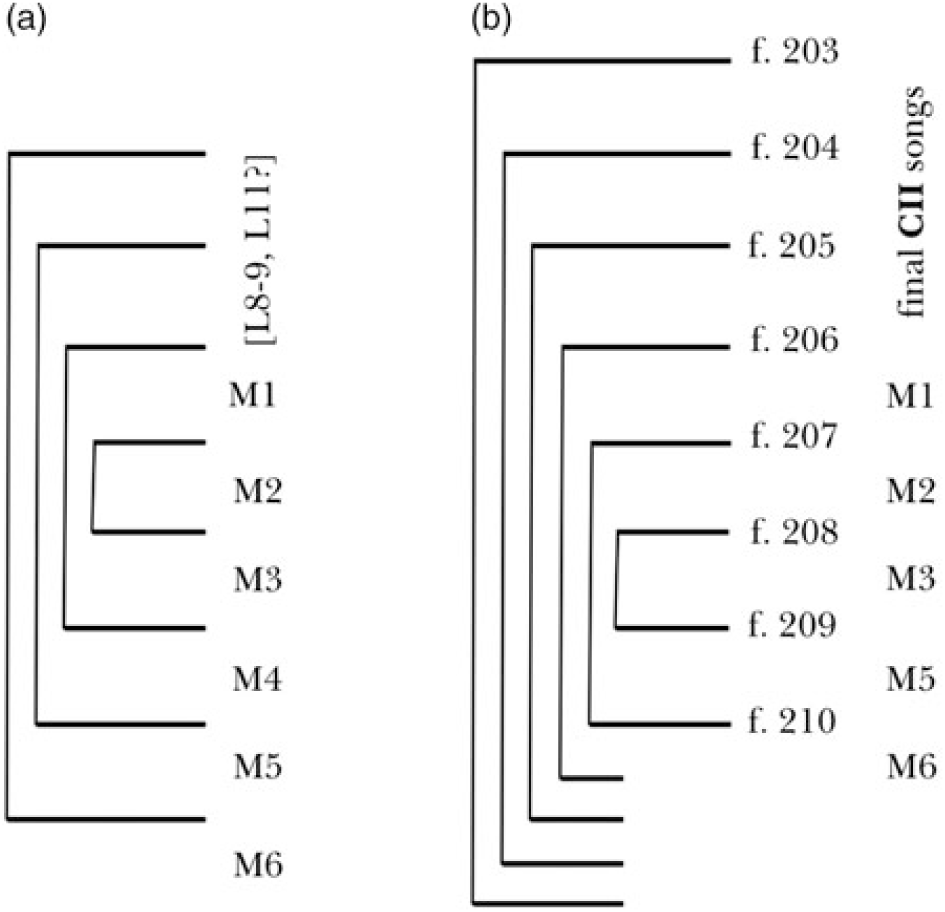

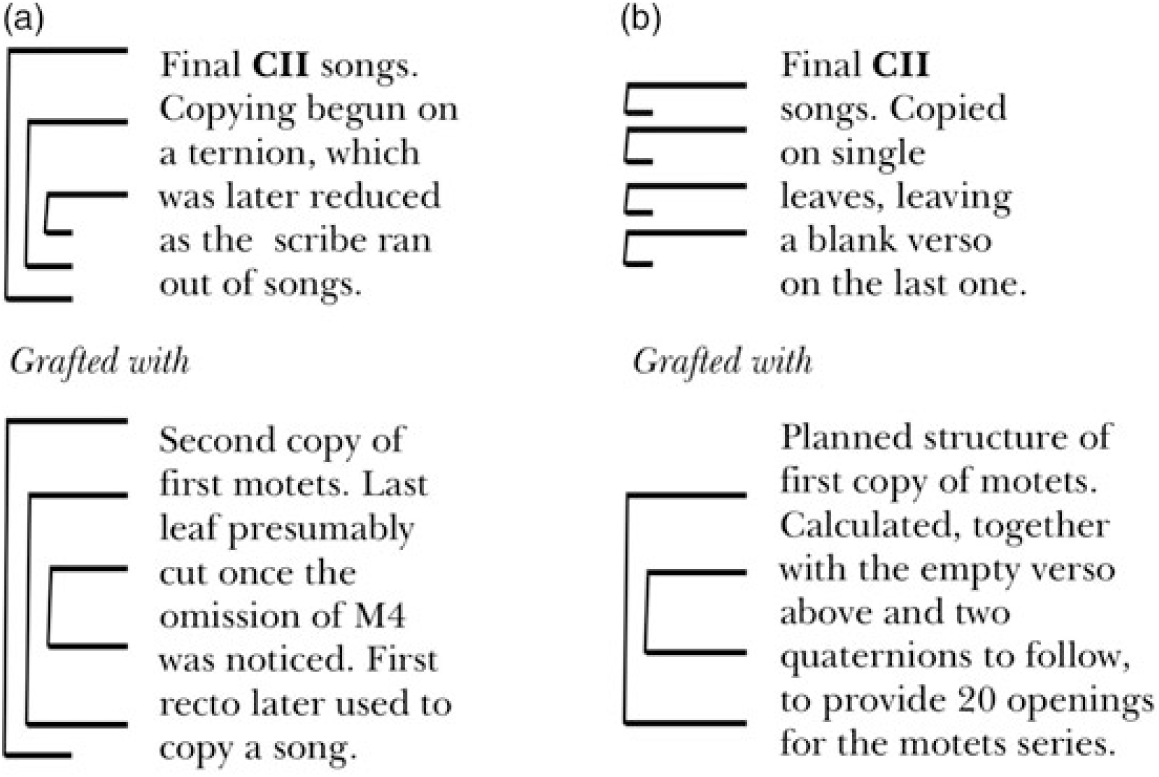

As certain motets have been dated to the 1320s and 1330s, the currently accepted view of MS C's creation places the collection as part of the temporal orbit of CI. Earp suggested it was copied early on as a stand-alone group of gatherings for inclusion after gathering XXIII, with its first gathering recopied as a result of the integration of the CII additions.Footnote 103 Having removed the temporal need to associate the motets with CI, we have little to go on when considering whether they were copied before or after the CII songs. One clue is the omission of the motet De Bon Espoire/Puis que la douce/Speravi (labelled M4 due its stable position in Machaut's later collections) from this manuscript. Earp's explanation sees the omission as a small error brought about by the recopying mentioned above: the turning over of two leaves rather than one.Footnote 104 I suggest that this explanation works better within a single rather than a double copying process. After all, Scribe A would have been more likely to notice the omission if he or she had already copied the missing work once before. Other issues for consideration include the structural anomaly of gathering XXVI and the empty spaces left at the end of the motet collection (gathering XXVIII) and on fol. 186v (end of gathering XXIII). I will consider them here in the order in which they appear in the manuscript. According to Earp's later-integration theory, fol. 187r originally opened a gathering on which the first copy of the motet collection's beginning was to be found (see Figure 1(a)).Footnote 105 It is rather surprising that the independent, multi-gathering copying process envisaged should not result with a structure mirroring that of a dit, that is, starting with regular quaternion gatherings and adjusting the final gathering as is necessary. That this did not occur can be explained either by a compiler's decision to end the manuscript with a full gathering, or as the result of through-copying comparable to the songs of CI. The first option fails to explain why this easy to lay out section left the last opening of the final gathering empty. The second option was discussed in relation to the lais and is contradicted by the interruption of the group of lais on fol. 186v. As Earp concedes, the placing of the non-musical lais L8, L9 and L11 before the motets in a hypothetical early version of gathering XXIII does not explain this anomaly.Footnote 106 It more likely implies an expectation for the integration of further additions into the manuscript before work on CI ceased.

Figure 1 (a) Earp's presumed original plan for CI; (b) current structure

The structure of gathering XXVI is rather mysterious: while its contents would fit perfectly on a quaternion, it uses only two full bifolia at its end preceded by four cut bifolia, or single sheets (see Figure 1(b) above). It seems clear that two elements have been grafted together here, as the transition from cut to full bifolia more or less correlates with the transition from CII songs to motets. The question is whether, as Earp suggests, the motet structure was re-planned to end with the beginning of M6 (as gatherings XXVII and XXVIII were already in existence), or whether the current structure was planned for the motet collection's first copy.

In both readings, it seems the compiler had difficulties estimating the amount of space required for the last few songs before the motets were to begin, either because their state made this difficult, or because it was not clear whether more would require copying. The recopying hypothesis necessitates the re-planning of the first five and a half motets. This requires five and a half openings and thus the preparation of a ternion. In order to explain the stub of the outer bifolio of this group, one would have to imagine the text scribe noticing the omission of M4 – in itself not surprising as he or she would have run out of exemplar materials before reaching the last verso of the gathering – but deciding to cover up the error by cutting the last leaf of the gathering rather than owning up to the mistake and recopying the relatively small amount of material for the third time (see Figure 2(a)). While possible, I would argue that the multi-agent character of professional manuscript production makes such underhand tactics difficult to get away with. The other option – that the motets were copied after the songs of CII – requires only the preparation of two bifolia here, as the empty verso of the single leaf that is now fol. 206 could easily have been taken into account (see Figure 2(b)). The existing structure of two bifolia followed by two quaternions would thus provide the exact number of openings for twenty motets to be copied, using the last gathering to its full. This option removes the need to arrive at M6 at a specific point in the structure, and to have copied M4 once already. Thus, it is possible for the omission to have gone unnoticed. The final empty opening may just as likely have been seen as a planning rather than a copying error. While both readings are technically viable, the prior copying of the motets requires a few more production stages and involves a couple more open questions than the consecutive copying option. To be convincing, however, it demands an alternative interpretation of the inclusion of the CII songs.

Figure 2 (a) Earp's suggested grafting process; (b) my suggested grafting process

THE CII SONGS AND SOME NOTES ON THE RONDEAUX

We have seen how the contents of CI seem to mirror a logical exemplar structure consisting of dits in self-contained units; two quaternions and a quinternion for the Loange; a quaternion of ballades and another of virelais; and three quaternions of lais. Tellingly, CII does not contain enough works in any single genre to fill another dedicated exemplar quaternion. This raises the possibility that the primary difference between CI and CII songs may only be the ease with which they could be integrated into structured, generically-based quaternion exemplars.Footnote 107 In this context, it is interesting to note that all the CI ballades are set to two voices, even though the Remède testifies that Machaut was already experimenting with four-part ballade composition by this point in time.Footnote 108 While potentially carrying chronological implications, this organising principle can also be read as a technique to control space and layout. According to this view, the prime parameter for inclusion in the quaternion exemplar of the CI ballades was Machaut's (or his secretary's) ability to create a consistent presentation. The easiest way to achieve this was to organize first all the works that conformed to the most popular setting size. Chronological and narrative ordering would thus have been a secondary consideration.Footnote 109 If this notion is accepted, strict compositional chronology and generic developmentalism is taken out of the equation. While some CII songs may have been brand new, others could have been just as old as the CI compositions. Two-part ballades may pre-date or post-date each other regardless of the section in which they appear, and three-part songs need not have been composed only after the creation date of the works in CI.

This leads us to the rondeaux. Apart from the one incorporated in the Remède, all the musical rondeaux in MS C appear within CII. The current understanding of this section thus suggests they were set to music after 1349. This would be rather counterintuitive. After all, the rondeau is the only literary fixed-form genre for which we can securely identify a tradition of polyphonic musical settings clearly pre-dating Machaut.Footnote 110 Furthermore, since Machaut had already written many rondeaux texts, I find it hard to believe that he would have needed the experience of composing dozens of settings in other, more complicated textual genres before tackling this relatively simple one. The appearance of rondeaux as motet tenors further weakens this stance.Footnote 111 Finally, it is also telling that the Remède rondeau – placed last in the descending order of difficulty presented in this dit – is a mature, three-part work unlikely to be a first attempt.Footnote 112 Only a few years later Machaut recommended this genre as a good starting point for a budding (admittedly, literary) artist in the Voir dit.Footnote 113

Nine rondeaux appear in CII. Being short and non-strophic, their notation requires little space. Altogether, only six sides are needed, far short of the sixteen sides offered by a quaternion. Following on from the analyses of the separation between CI and CII ballades, virelais and lais, I contend that this is the very reason they do not appear in CI: Machaut had simply not yet come up with a mechanism to organise them into a unified gathering. Once again, an awareness of the absence of a whole genre (perhaps two, if the motets were yet to be copied) makes more sense of integrating the CII materials regardless of the extra work this involved and its detrimental effect on the uniformity and look of the manuscript as a whole.Footnote 114

As previously recognised, the songs in CII can be divided up into two sections.Footnote 115 Omitting B19, the first twenty songs appear in small generic groupings (see Table 2). As discussed above, the lais bridge the two sections and some of the non-musical works appearing here may in fact have belonged to the CI materials. Virelais and ballades follow in the same order in which they were presented in CI, with the new genre (new to the manuscript, not in terms of composition) – the rondeaux – at the end. The exchange in the order of R2 and B24 was probably due to a planning error. When ruling fol. 201v, the scribe estimated correctly that the music of B24 would require four and a half lines but failed to allow room for double underlay under the first two lines, destined to contain the musical repetition of each strophe's A section. A short rondeau – a genre not requiring text stacking – was copied instead, leaving a stave's worth of space empty.Footnote 116 The correct arrangement for the final ballade of the group was then rather inelegantly ruled underneath.

Table 2 Songs of CII using Ludwig numbers, specifying only beginning folio

* denotes works without musical setting.

1 I take all songs which were not copied as presented in the CI exemplar (that is, also lais contained there but held up for copying later) to be CII songs. As my explanation for their copying (and that of the motets) removes the need for a break between the two layers, the exact point of transition has fewer implications in any event.