Adolescence is a time of physical, mental and social development and habits established during these years tend to continue into adulthood(Reference Craigie, Lake and Kelly1,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Wall and Larson2) . Adolescent nutrition is gaining increasing attention for its role as a crucial stage in life to optimise health and health-related behaviours(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3). Much research on adolescent nutrition addresses the content of what is being eaten, in terms of food sources and nutrient intakes, with adolescent diets rarely meeting nutrition recommendations(Reference Rippin, Hutchinson and Jewell4). Whilst measuring dietary intake is a crucial aspect to understanding diet and health, more work is needed to fully understand the practical, social and psychological considerations of adolescents when choosing foods.

The purpose of this review is to summarise what is known about the motivations for food choices among adolescents, exploring how and why they eat and not only what they eat, with a particular emphasis on the Irish context. The amount of data regarding food choice in Irish adolescents is relatively limited, but the patterns of eating and motivations for food choice identified in Ireland are similar to most other adolescent populations. To give context to motivations for food choice in this age group, this review will highlight the importance of this life stage as a time of transition and development of lifestyle behaviours, and will discuss numerous concerns for adolescents, which may influence their food choices and eating habits in different ways.

Adolescence as a time of development

Adolescence is the period of time when a child transitions towards adulthood. The WHO defines adolescence as the broad age range from 10–24 years(Reference Sawyer, Azzopardi and Wickremarathne5). This is further broken down into early adolescence (10–15 years), late adolescence (15–18 years) and early adulthood or ‘emerging adulthood’ (18–24 years)(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3,Reference Arnett6) . The term ‘adolescent’ or ‘teenager’ generally encompasses the ages between 13 and 18 years old, and an adult is considered anyone older than 18 years old, which, in most countries, is the age of legal independence(Reference Sawyer, Afifi and Bearinger7). Whilst different terms are used interchangeably throughout the published literature, and different research focuses on specific sub-groups of adolescents, in this review the term ‘adolescent’ will be used when referring to any details for the age group ranging from 10 to 18 years, i.e. those in early adolescence and all teenagers.

In many developed countries, the teenage years coincide with the years in post-primary school, meaning a combination of biological, mental and social changes occur simultaneously through puberty and increasing independence from parents(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3,Reference Sawyer, Afifi and Bearinger7–Reference Morgan, Thornton and McCrory10) . During the teenage years, adolescents are forming their own individual identity in a world of age-related social norms and restrictions(Reference Morgan, Thornton and McCrory10,Reference Erikson11) . This can be challenging for adolescents, who may feel such as they are mature and able to make their own rational decisions, but do not have the legal or financial freedom to do exactly as they wish. Finding the right balance between developing their own personality and interests whilst following social, cultural and peer norms can be a challenge during the adolescent years(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3).

Health behaviours in adolescents

The complex interaction between biology, the environment and the social context of a person as key components in human development has been well described through the Bronfenbrenner bio-ecological model of human development, which acknowledges the wide range of influential factors on human behaviour(Reference Bronfenbrenner, Morris, Lerner, Damon and Lerner12). At the centre of the model is the person and their level of the independent agency in making decisions on whether to engage in health-promoting or health-compromising behaviours. However, these decisions take place under the influence of the wider social context in which they live, including family, peer, school, community and wider environmental influences on health and physical development, as well as their beliefs and values system(Reference Morgan, Thornton and McCrory10,Reference Bronfenbrenner, Morris, Lerner, Damon and Lerner12) . The interactions between the external food environment and an adolescent's personal food system, i.e. the things an individual has control over themselves, are important when understanding what active considerations and social negotiations are taking place when an adolescent is making a food choice(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Connors, Bisogni and Sobal14) . While the parent–child relationship has a strong influence on decisions and behaviours among younger children, during the teenage years, the peer influence increases and the parent influence decreases(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3,Reference Viner, Ozer and Denny9,Reference Morgan, Thornton and McCrory10) . The influence of wider society also increases among adolescents, as they become more independent and interactive with environments external to the family unit(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3). Adolescents are particularly receptive to positive influences from social and emotional learning and behavioural modelling, since the adolescent brain is still developing rapidly(Reference Morgan, Thornton and McCrory10,Reference Steinberg, Dahl, Keating, Cicchetti and Cohen15) . However, they can also be easily influenced by the negative behaviours of peers(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3,Reference Viner, Ozer and Denny9) . Behaviours and habits developed during adolescence tend to persist into adulthood, particularly in relation to health and eating behaviours(Reference Craigie, Lake and Kelly1,Reference Sawyer, Afifi and Bearinger7,Reference Morgan, Thornton and McCrory10) .

There is evidence to suggest that interventions during adolescence are effective in modifying behaviours. Researchers analysing data from the ‘Growing Up in Ireland’ survey found that problematic behaviours identified in younger school-aged children do not always predict similar problematic behaviours in late adolescence(Reference Smyth and Darmody16). Smoking initiation often begins in the teenage years, but the rates of smoking among Irish adolescents have reduced from 21 to 11 % between 1998 and 2018(Reference Friel, Nic Gabhainn and Kelleher17,Reference Költő, Gavin and Molcho18) . Two characteristics of the adolescent mindset are poor risk perception and a need for instant gratification(Reference Sawyer, Afifi and Bearinger7), making it difficult for adolescents to resist the peer pressure and the nicotine high from smoking, similar to the tendency to consume high sugar and high-fat foods(Reference Rippin, Hutchinson and Jewell4,Reference Hearty and Gibney19) , with little consideration for the future health effects(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3,Reference Sawyer, Afifi and Bearinger7) . While smoking is still a ‘risky’ behaviour undertaken by adolescents(20), the reduction in rates shows that the teenage years can be an effective period to prevent negative health behaviours and to promote positive health behaviours.

Health needs and weight status in adolescents

During adolescence, rapid growth and body composition remodelling occur along with the hormonal changes characteristic of puberty(Reference Patton and Viner8,Reference Das, Salam and Thornburg21) . This gives adolescents more specific nutrient needs than younger children or adults, and sex differences begin to appear(Reference Das, Salam and Thornburg21). Nutritionally, adolescents have increased energy, protein and calcium needs, in line with their changing body composition and establishment of peak bone mass, and increased iron needs, especially in females with the onset of menstruation(Reference Das, Salam and Thornburg21). The effects of hormones cause different body composition outcomes in males and females, with females having greater fat deposition and weight gain around the hip area, and males having greater muscle mass and weight gain around the shoulder area(Reference Patton and Viner8,Reference Das, Salam and Thornburg21) . As adolescent girls reach puberty and begin to menstruate, they enter the ‘child-bearing years’, and therefore have increased requirements for energy and several micronutrients including iron, folic acid and iodine to support a potential developing child(Reference Das, Salam and Thornburg21,22) . These developments occur at different stages in different individuals during these years of puberty, which have both physical, psychological and social impacts(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3,Reference Patton and Viner8,Reference Viner, Ozer and Denny9,Reference Das, Salam and Thornburg21) .

Across the globe, we see the double burden of disease present in adolescent populations, with both malnutrition and rates of overweight and obesity remaining high or even increasing(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3,Reference Bentham, Di Cesare and Bilano23) . The presence of either of these conditions can have negative health effects for the individual and for the population as a whole(Reference Sawyer, Afifi and Bearinger7). Adolescence is now considered a second developmental period, after the initial fetal and infancy developmental period of the first 1000 days(Reference Scott24), which can help make up for developmental disadvantages experienced in early life and can set the basis for positive (or negative) health and lifestyle behaviours for future adult life(Reference Viner, Ozer and Denny9). Ensuring optimal nutrition in adolescents is therefore of crucial importance. Recent data suggest that rates of overweight and obesity are increasing in Irish adolescents(25). The impact of this weight status tends to have a stronger impact on future physical health later in adulthood, but more adolescents are presenting with diet-related non-communicable diseases than previously(26,Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay27) .

Improving diet quality is an important aspect of improving the weight and health status of a population(28). Although it is widely accepted that providing knowledge on healthy eating alone is not enough to change and sustain eating behaviours(Reference Tombor, Michie and Braddick29,Reference Gill and Boylan30) , health promotion messages are one of the best, low-cost interventions available, with the potential to be highly cost-effective when targeted at younger people(Reference Merkur, Sassi and McDaid31). To address the issue of overweight and obesity in the adolescent population, it is important to find ways to make healthy-eating messages more effective and relevant to the target population. Many weight-gain prevention interventions fail to produce the desired results, but those that focus on multiple health behaviours and not only weight alone tend to be more effective(Reference Stice, Shaw and Marti32). Thus, focussing on improving multiple health behaviours such as smoking and eating habits not only weight management, and emphasising the key values held by adolescents directly could be more effective in changing and sustaining positive diet habits, and may also lead to improvements in weight status(Reference Stice, Shaw and Marti32,Reference Bryan, Yeager and Hinojosa33) .

Dietary intakes and eating habits in adolescents

Four large surveys have been conducted among Irish adolescents over the past 20 years, with a focus on diet appearing in each to varying degrees(Reference Költő, Gavin and Molcho18,25,34,35) . The key dietary data from the surveys are summarised in Table 1. The most comprehensive dietary intake data comes from the IUNA National Teens' Food Surveys(25,36) . In general, Irish adolescents do not meet standard dietary recommendations(Reference Rippin, Hutchinson and Jewell4,37) . Some positive trends are showing over time in the Irish adolescent diet(Reference Gavin, Költő and Kelly38), such as increasing consumption of fruit and water, and reducing intakes of sugar and salt(25,Reference Gavin, Költő and Kelly38) . While sugar, salt, saturated fat and fibre intakes are still outside the recommended levels for adolescents, the intakes have changed in a positive direction over the past 15 years(25).

Table 1. Summary of findings from recent surveys conducted in Irish adolescents

NTFS, National Teens' Food Survey; FFQ, Food Frequency Questionnaire; N/R, Not Reported. F&V, Fruit & Vegetables; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverages.

* Full survey collected data for all adults >15 years, figures for 15–24-year-olds reported here.

† Overweight/obesity data not reported in 2018 so 2019 data used. No dietary data in 2019 report.

‡ Foods high in fat, sugar and salt(22).

§ Crisps or savoury snacks; biscuits, doughnuts, cakes, pies, chocolate.

|| Reported as ‘unhealthy foods’ – sweets, cakes, biscuits, salted snacks, pastries & take-aways.

¶ Data for all adults >15 years, no segregated data reported on this measure.

Some eating habits are commonly measured in national surveys, including fruit and vegetable consumption, consumption of snack foods, intakes of added sugar and methods for dieting or weight loss (Table 1)(Reference Költő, Gavin and Molcho18,35,Reference McNamara, Murphy and Murray39) . There are subtle but important differences in the diet habits and food choices in adolescents compared with younger children and adults, likely based on the level of independence, autonomy and skill they have about food(25,40,41) . While we have a relatively strong understanding of the content of what Irish adolescents are eating, we need to understand more about the context in which they eat, and what the motivating or influential factors are that drive their food choices

Body dissatisfaction, dieting & disordered eating in adolescents

Research has shown that adolescents display high levels of body dissatisfaction, resulting in a desire to change their body shape(Reference Költő, Gavin and Molcho18,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42) . Data in Irish adolescents also suggests high levels of body dissatisfaction(Reference McConnon, Burke and McCarthy43), and the 2019 ‘My World Survey’ identified that only 46 % of Irish adolescents were satisfied with their bodies, with boys more likely to be satisfied than girls (59 % vs. 38 %)(Reference Dooley, O'Connor and Fitzgerald44). A recent analysis of trends in health behaviours showed that, over the past 20 years, the rates of dieting have increased in Irish adolescents, as a means to change their body size(Reference Gavin, Költő and Kelly38). Regarding body image and dieting behaviours, 15 % of Irish children and adolescents were dieting to lose weight in 2018, an increase from 12 % who were actively on a weight-reducing diet in 2006(Reference Költő, Gavin and Molcho18,Reference Nic Gabhainn, Kelly and Molcho45) . Girls generally believe they are too big so change their eating habits and increase their exercise to lose weight or to prevent gaining weight, whereas boys generally believe they are too small or thin, so eat more food or exercise more to ‘bulk up’ or gain weight(Reference Gavin, Költő and Kelly38,Reference McNamara, Murphy and Murray39,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Dooley, O'Connor and Fitzgerald44) . Those who are classified as being overweight or obese tend to use these diet and exercise habits to lose weight more than those classified as normal weight(Reference McNamara, Murphy and Murray39). Both diet and exercise are used as means to change body size, but rates of extreme exercise have not changed dramatically over the past 20 years, whereas the reported habits about active dieting have become more pronounced in Irish adolescents(Reference Gavin, Költő and Kelly38). This suggests that changes to diet habits are the main ways Irish adolescents attempt to change their body size. Possibly more concerning is that body dissatisfaction and dieting behaviours are beginning at a younger age, and this desire to be thin is common among adolescents in all societies around the world(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). The most common dieting practices used among adolescents to change their body shape include eating more fruit and vegetables, more protein-rich foods, more grains and drinking more water, as well as eating less fat or oil, less sugar and eating smaller portions(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). Similar trends in eating have been identified in recent Irish data over the past 15 years(25,36) . On the surface, these eating habits appear to be quite positive in terms of the effect on health, however, if the underlying motivation is to change their body size or their appearance rather than to specifically improve their health, the impact of these diet behaviours may be more damaging than intended(Reference Das, Salam and Thornburg21,46–Reference Koven and Abry48) .

The concept of dieting during the teenage years continues to be a cause for concern, particularly as the ‘thin ideal’ becomes more prominent through television and social media(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,46,Reference Holland and Tiggemann49) . Although dieting behaviours, such as restrictive eating, tend to be higher among adolescents classified as overweight(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Hannan47,Reference Daly, O'Sullivan and Walton50–Reference Snoek, van Strien and Janssens54) , with high rates of body dissatisfaction among adolescents in general, it is often the perception of being overweight that results in attempts for weight loss, regardless of whether the adolescent is classified as overweight or not(Reference McNamara, Murphy and Murray39,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,46) . Dieting and restrictive eating are ineffective methods for achieving long-term weight loss(Reference Herman and Mack55–Reference McEvedy, Sullivan-Mort and McLean58), however many adolescents still strive for a smaller body and a lower body weight, often resulting in nutritional deficiencies, disordered eating habits and poorer health outcomes later in life(46,Reference Nagata, Garber and Tabler59) . Dieting and disordered eating habits that begin in adolescence do tend to carry on into adulthood, so preventing these eating behaviours from the beginning is an important element of nutrition education for adolescents(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Wall and Larson2). Poor body image, body dissatisfaction and being overweight are key predictors of dieting or disordered eating habits, all of which are concerns in Irish adolescents(46). Recent evidence has shown that using a more intuitive eating approach, i.e. eating in line with hunger and satiety cues and focussing more on health-gain rather than weight loss, during adolescence reduces disordered eating behaviours later in adulthood, and improves physical and psychological health markers(Reference Hazzard, Telke and Simone60,Reference Christoph, Järvelä-Reijonen and Hooper61) . Elements of intuitive eating(Reference Tribole and Resch62) could be beneficial as a component of the diet and health promotion programs directed at adolescents and young adults, to support healthy eating while aiming to avoid disordered eating habits.

On a population level, it is difficult to identify the prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating, due to the sensitive nature of the topic and relevant data are not always collected in national nutrition surveys(Reference Santomauro, Melen and Mitchison63). Research suggests that eating disorders affect 55⋅5 million people worldwide(Reference Santomauro, Melen and Mitchison63). The age of onset for eating disorders is usually during adolescence(Reference Lock and La Via64), and in Ireland, two-thirds of all eating disorder cases are in adolescents(65). While eating disorders have specific diagnostic criteria, disordered eating, or orthorexia, exists on a spectrum that ranges from normal eating habits through to clinical eating disorders, and is defined as ‘an unhealthy obsession or preoccupation with food, characterised by a restrictive diet, strict patterns of eating and avoidance of certain foods believed to be unhealthy’(Reference Koven and Abry48,Reference McComb and Mills66) . Orthorexia nervosa is considered a pathological preoccupation with healthy eating, while healthy orthorexia is more being interested in healthy eating(Reference Depa, Barrada and Roncero67). It can be easy to confuse disordered eating with healthy eating, since the actions and habits themselves can appear to be positive for health, but if eating a certain way is purely to lose weight or to prevent weight gain, the net effect may not be positive for health(46). Orthorexia is likely to change eating habits and food choices, and it may lead to medical issues, nutritional deficiencies and a poorer quality of life due to the high restriction and food obsession(Reference Koven and Abry48,Reference Depa, Barrada and Roncero67) . While the topic of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in adolescence could warrant its own full review, it is noted here to acknowledge the impact body image concerns or body dissatisfaction can have on eating habits and health, particularly among adolescents who are vulnerable to peer and social concerns about their changing bodies(Reference Depa, Barrada and Roncero67,Reference Mousa, Al-domi and Mashal68) .

Adolescents' interest in their health

Adolescence is a time when risk-taking behaviours tend to begin, with adolescents preferring more instant gratification rather than being concerned for long-term health, which might suggest that adolescents don't place high importance on their health(Reference Sawyer, Afifi and Bearinger7,Reference Morgan, Thornton and McCrory10,Reference Bryan, Yeager and Hinojosa33) . However, specific research on the topic of health suggests that adolescents tend to be concerned for both their immediate and longer-term health, but there are often practical barriers that limit their ability to make health-promoting food choices(Reference McNamara, Murphy and Murray39,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42) . Health was ranked the second most important thing in the lives of young people in a recent survey in Ireland(Reference McNamara, Murphy and Murray39). Adolescents' understanding of health varies around the globe, but health is considered important by most adolescents and they understand the important role food plays in preventing disease and promoting good health(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). Adolescents also understand the connection between physical and mental health and wellbeing, in line with the WHO definition of health as ‘a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmary’(69). Irish adolescents have noted a strong connection between health and happiness(Reference Higgins, Sixsmith and Gabhainn70). Some other interpretations of what health means to adolescents around the world relate to being in good physical shape, being free from disease, having energy for school and daily activities, or maintaining a balanced lifestyle by eating well and being physically active(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Borraccino, Pera and Lemma71) .

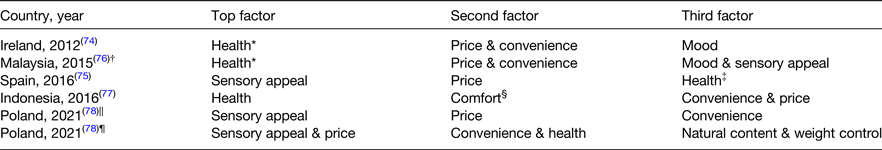

This range in explanations provided shows that adolescents understand ‘health’ to be multifaceted, encompassing disease, physical and mental health aspects, which may differ from the definition of ‘health’ used in nutrition-specific research, which often focuses solely on the healthfulness of foods. The Food Choice Questionnaire (FCQ) is a quantitative tool widely used to assess motivations for food choice, with ‘health’ being one specific motivating factor regularly featuring high in the list of motivations(Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle72,Reference Cunha, Cabral and Moura73) . ‘Health’ in the FCQ relates to the nutrition content of food and how that might benefit the body(Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle72). There are a limited number of studies using the FCQ in adolescents, but they show a unique depiction of the importance that health plays in food choices, and how the value of health differs between adults and adolescents(Reference Cunha, Cabral and Moura73). A summary of the top three most important factors from studies using the FCQ in adolescents is provided in Table 2. In these adolescent cohorts, the original ‘health’ factor often merges with other factors of ‘natural content’ and/or ‘weight control’, suggesting that adolescents view these reasons for food choice as similar(Reference Share and Stewart-Knox74–Reference Ooi, Mohd Nasir and Barakatun Nisak76). In Irish adolescents, the authors noted that the concept of health should be expanded to include constructs of body weight control and the natural content of food, since all three factors merged together in their analysis of FCQ responses(Reference Share and Stewart-Knox74). Similarly, in Malaysian adolescents the factors of health, weight control and natural content merged to form one comprehensive factor(Reference Ooi, Mohd Nasir and Barakatun Nisak76). Spanish adolescents considered health the most important factor in their food choices and it combined with the natural content of food, but remained separate from weight control, which was further down the list of priority, and weight control was more important for girls than boys(Reference Canales and Hernández75). In Indonesian adolescents, a modified version of the FCQ was used and only three main motives for food choice were identified and named as ‘comfort’, ‘convenience & price’ and ‘health’(Reference Maulida, Nanishi and Green77). Interestingly in this study, elements of the original natural content and weight control factors were removed from analysis completely, and males focused more on health than females here, which may be connected to the fact that weight control was not included in the analysis at all(Reference Maulida, Nanishi and Green77). A very recent study in Polish adolescents used the original FCQ tool before and during the Covid pandemic, and the authors reported that the importance placed on both health and weight control increased during the pandemic, for both boys and girls(Reference Głąbska, Skolmowska and Guzek78).

Table 2. Summary of the top three factors from studies using the Food Choice Questionnaire tool in adolescent cohorts

* Health combined with weight control and natural content.

† No specific ranking of factors as this was a validation study. Media, peers & parents were other influences identified.

‡ Health combined with natural content.

§ New comfort factor composed of three mood items and two sensory appeal items.

||Data collected before the Covid-19 pandemic. The fourth most important factors before the pandemic were health, mood & natural content joined.

¶Data collected during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The close connection between the FCQ items relating to health, natural content and weight control in adolescent research suggests that the adolescent perception of health in relation to food is closely linked with the impact that food might have on their weight or physical appearance. Furthermore, there may be differences in the interpretations or value of health between boys and girls. However, health regularly features in the top three most important motivating factors for adolescent food choice, showing that adolescents value the impact food can have on their health when making food choices.

Barriers and facilitators for healthy food choice in adolescents

As outlined above, having good health is a key priority for adolescents, and they understand that their actions now can affect their health in the future(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). Recent data from Irish adolescents indicated that “family” was still the most important thing in the lives of young Irish people, with “health” in second and “friends” the third most important element in their lives, with all three elements potentially affecting their diet habits and food choices(Reference McNamara, Murphy and Murray39). During adolescence, the peer or social influence becomes much greater than the parental influence, which dominated more during childhood(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3). However, adolescents are still dependent on their parents to a large degree, as they tend not to have complete financial autonomy or legal independence(Reference Sawyer, Afifi and Bearinger7). Adolescents do understand that food and nutrition play an important role in their health and wellbeing, and good nutrition was noted as important for 99 % of adolescent participants in the global ‘Food & Me’ study, as a way to prevent illness, ensure they grow and develop correctly, and to set themselves up for a healthy and prosperous future(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). The vast majority of research on adolescent food intakes shows that adolescents rarely follow healthy eating guidelines, consuming high amounts of confectionary or processed foods, and low amounts of fruits and vegetables(Reference Rippin, Hutchinson and Jewell4,25) . As well as knowing the content of adolescent diets, we also need to understand more about the context of their diets and why they struggle to follow healthy eating guidelines, despite their knowledge of the importance of nutrition.

Despite health being important to adolescents, they face many barriers to eating healthy foods. These barriers include their understanding of a healthy diet, taste preferences and the temptation of less healthy foods, their ability to access healthy foods and healthy food being too expensive, and different social and food environment concerns that promote or discourage the consumption of health-promoting foods(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79–Reference Kebbe, Damanhoury and Browne82) . Many studies have attempted to identify the barriers to healthy eating among adolescents, but it is also important to know about the factors that actively motivate or drive certain food choices. Barriers to healthy eating tend to be both individual and external, whereas facilitators tend to be external or interpersonal(Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees81,Reference Kebbe, Damanhoury and Browne82) , but often the same factors that act as barriers also act as facilitators in different circumstances; hence they are grouped together in the sub-sections below, which will be discussed in turn.

Health and nutrition knowledge

A lack of knowledge on healthy eating is often proposed as the reason why adolescent diets are unhealthy, however, most recent research suggests adolescents have a relatively good understanding of a healthy diet, but struggle to implement it(Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79,Reference Browne, Barron and Staines80) . For example, in a study in Ireland, adolescents demonstrated a high level of knowledge on good nutrition but felt they struggled to act on it due to their food environment(Reference Browne, Barron and Staines80). Although adolescents show a strong interest in and a good understanding of the importance of health and nutrition, this level of knowledge varies depending on the location and socioeconomic background of adolescents, with many adolescents often being unclear on which foods are needed to promote good nutrition and health(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). Information on healthy eating comes mostly from school textbooks, public health campaigns, family or friends and more often now from social media or online(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). The sources and quality of this online information, misinterpretation of information, or conflicting assumptions about foods often lead to a mixed level of knowledge on food and nutrition, which in turn can affect consumption habits(Reference Klassen, Douglass and Brennan83–Reference Turner and Lefevre86). Foods are often dichotomised as ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and the foods described as being ‘bad’ or unhealthy are often due to the assumed effect on weight gain(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). Connected to nutrition knowledge, adolescents also report practical barriers to healthy eating, such as a lack of skills or ability to cook or prepare healthy foods, even if they know what they should be eating(Reference McNamara, Murphy and Murray39). Adolescents have directly identified a need and desire for clear, accurate and relevant nutrition information and the development of food preparation skills, so they can make health-promoting food choices and are able to access and prepare these foods for themselves(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Browne, Barron and Staines80) .

Taste

Taste is consistently reported as playing a strong role in adolescent food choices, acting as both a barrier and a facilitator to healthy eating(Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees81,Reference Kebbe, Damanhoury and Browne82,Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon87–Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry89) . While individual taste perceptions and preferences vary among individuals, adolescents tend to have a greater preference for sweet tastes over bitter tastes(Reference Bawajeeh, Albar and Zhang90). Adults tend to prefer or tolerate bitter-tasting foods more, potentially due to the higher awareness among adults of the health benefits of bitter-tasting foods and the negative health effects of sweet foods(Reference Bawajeeh, Albar and Zhang90). Even though adolescents are aware of the role food plays for health, competing interests for taste and other sensory rewards often take preference over the healthfulness of the food(Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett88). Interestingly, data from the FCQ tool shows taste or sensory appeal as having a mixed influence on adolescent food choice (Table 2). The sensory appeal is a proxy for taste in the FCQ, although there is only one specific item for ‘tastes good’. Spanish adolescents placed the sensory appeal at the top of their priorities(Reference Canales and Hernández75), while Malaysian and Indonesian adolescents connected sensory appeal with their mood and it was lower down in influence on their food choices(Reference Ooi, Mohd Nasir and Barakatun Nisak76,Reference Maulida, Nanishi and Green77) . Sensory appeal remained the top motivation for food choice in Polish adolescents both before and during the Covid-19 pandemic(Reference Głąbska, Skolmowska and Guzek78), whereas in Irish adolescents, the sensory appeal did not feature in the list of determinants for adolescent food choice(Reference Share and Stewart-Knox74).

However, when combined with qualitative data, where taste is often noted as being highly important, it is clear there is more to understand on this. In Ireland, taste was reported as a key barrier to healthy eating, where Irish adolescents disliked the taste of many healthy foods and found less healthy foods more tasty and tempting(Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett88). This is echoed in most research in adolescents globally(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees81,Reference Kebbe, Damanhoury and Browne82,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry89,Reference Wippold, Tucker and Smith91) . Taste itself might not be a driving factor for the choice of healthy foods, but the taste and temptation of less healthy foods cause these to be chosen more readily(Reference Kebbe, Damanhoury and Browne82). Food considered as healthy is often assumed to taste bad, and adolescent taste preferences tend to be higher for the less healthy, sugar-rich, treat foods, the temptation of which they find difficult to resist(Reference Hearty and Gibney19,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon87,92) . Even if there is healthy food available that tastes nice, the presence and temptation of less healthy and better-tasting foods make it difficult for adolescents to choose the healthier option(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Kebbe, Damanhoury and Browne82) . If healthy foods are to be more readily consumed, they need to taste good(Reference Kebbe, Damanhoury and Browne82). Additionally, taste combines with convenience and cost, where less healthy food is often cheaper(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees81) . Therefore, elements of taste, sensory appeal and temptation are factors that act together and interact with other factors as both barriers and potential facilitators of healthy food choices in adolescents.

Cost and convenience

The affordability of more expensive, healthier food options is a concern for adolescent consumers, with convenience and the cost of different foods acting mostly as a barrier for healthy food choices(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Share and Stewart-Knox74,Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79,Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees81,Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon87,Reference Wills, Backett-Milburn and Gregory93) . Adolescents tend to have busy schedules, with high demands from school, sports or recreational activities and their social lives, causing them to favour quick, easy-to-prepare foods that need little to no cooking or clean-up(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees81,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry89) . Data from the FCQ show that price and convenience regularly combine in their influence on adolescent food choices, appearing in the top three motivating factors throughout the research (Table 2)(Reference Share and Stewart-Knox74–Reference Głąbska, Skolmowska and Guzek78). Where there are healthy convenience foods available, these foods are often outside the budget of adolescents, particularly younger adolescents(Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79). Individual financial constraints can determine adolescents' food choices when they are buying their own foods, and value for money is noted as a concern for adolescents, with many food choices being made on ‘meal deals’ or special offers on foods(Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79). As stated in the ‘Food & Me’ report, and echoed throughout research globally, ‘healthy options need to be available at a price that adolescents see as affordable and competitive with unhealthy food choices’(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). This statement encompasses the idea that food needs to be healthy and affordable for adolescents, but that the adolescent must appreciate and value that these foods are worth the money. They must be as socially acceptable and as desirable as the unhealthy food options currently available and widely consumed, but more specific research is needed to establish what determines this specific value perception in adolescent groups(Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79).

Social concerns

As adolescents grow, their level of independence increases and time spent with peers becomes increasingly important to them(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli3,Reference Kenny, O'Malley-Keighran and Molcho94) . The most commonly reported drivers or influences from qualitative data appear to be their peers or close relationships, with friends and family reported as having the strongest influence on food choice(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). The quantitative FCQ tool does not include a specific factor relating to peer influence or social concerns, but socio-economic differences are often observed in research with this tool(Reference Cunha, Cabral and Moura73). This is a potential limitation of the original tool, particularly in adolescent populations. The social occasion about food is a popular activity in the lives of adolescents, with socialising often occurring at fast-food locations(Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79–Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees81,Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon87) . Social desirability and social norms about certain foods are key factors considered by many adolescents, where they don't want to eat ‘uncool’ or ‘weird’ foods around their peers(Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79,Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett88,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry89,Reference Wills, Backett-Milburn and Gregory93) . Given the increasing amount of time adolescents spend outside of the home and school environments socialising, there are more opportunities to make poor dietary choices, usually choosing foods that are high in sugar, salt and fat and that are often ultra-processed(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Rauber, Martins and Azeredo95,Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Molcho96) . The taste and affordable nature of these foods also make them desirable and popular as choices, as well as being easy to share with friends, and with fast-food locations providing a safe space for adolescents to socialise in(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79) . Aside from the quality and content of the foods eaten, the occasion of eating is one that supports fun and enjoyment, celebrating independence from their parents and fostering a sense of belonging among their peer community(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). Particularly among adolescents, the social side to food links closely with other factors of taste, access and affordability. In Ireland, friends were noted in the top three most important things in adolescent lives, further suggesting that peers might play a key role in determining their food choices along with other health or social behaviours(Reference McNamara, Murphy and Murray39). Harnessing the value placed on social concerns might be beneficial for improving adolescent diets, where framing healthy eating as a way to establish autonomy from parents and to favour social justice might help to improve the social status of healthy eating, thereby making healthy eating the popular way to eat(Reference Bryan, Yeager and Hinojosa33).

Food environment

Different considerations for food choice take place depending on where the adolescent is eating, be it at home, at school or in a social environment(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13). Adolescents tend to eat a third of their meals away from the home(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Story, Neumark-Sztainer and French97) , which means the external food environment is another strong influence on adolescent diets(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79) . The most common places to eat away from home are school, cafes/restaurants, stores, malls or parks and friends' houses, and the location varies depending on the time of day(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Rauber, Martins and Azeredo95) . Socialising with friends often involves eating more ultra-processed, takeaway or convenience foods, and usually, the occasion of socialising is more important than the food content itself, as described earlier(Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79,Reference Rauber, Martins and Azeredo95) . Family and the home environment are also important influences on food choice, and the media and online environment are becoming more important as influences on food choice among adolescents now as well(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees81,Reference Kebbe, Damanhoury and Browne82) .

School food environment

The school context varies widely between countries and even between individual schools, but when eating at school the most common practices, both in Ireland and other developed countries, are bringing in a packed lunch or buying food at the school canteen(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79) . In some situations, older adolescents can leave the school premises and purchase food from the nearby food environment, which often tends to be less health-promoting in nature(Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Gabhainn79,Reference Kelly, Callaghan and Molcho96) . The school environment has been noted mostly as a barrier to healthy eating, while also providing opportunities to promote and support more healthy food choices and healthy eating habits(Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees81). From the adolescents' perspective, the school food environment plays a highly influential role in their food choices. When healthy food options are not available or when school policies do not enforce healthy lunchboxes, it is difficult to find an incentive and opportunity to choose healthy meals and snacks(Reference Browne, Barron and Staines80,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry89,Reference Wills, Backett-Milburn and Gregory93) . Post-primary school adolescents in Ireland specifically noted a difference in the school food policy environment between primary and post-primary schools, and they requested more support from their schools to promote healthy foods and ban unhealthy foods(Reference Browne, Barron and Staines80). School policy plays a role in ensuring affordable, healthy food options are available in the canteen, and having school healthy eating policies in place to promote healthier lunch boxes for students can be helpful(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Browne, Barron and Staines80,Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees81) . Adolescents in several countries and school settings have specifically requested that they receive better quality nutrition education at school, more opportunities to learn and practice practical skills about cooking and food preparation, and better leadership on nutrition from teachers, parents and engagement from relevant health professionals, as reported in the ‘Food and Me’ study(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). Reported options for how to utilise the school environment to improve adolescent diets and health include the basic level of ensuring healthy food options are available and affordable in the canteen or nearby school environment, but also by improving and increasing the nutrition education and skills training provided to adolescents, who are willing and interested in learning and practicing healthy food habits.

Home food environment

The home environment is a place where adolescents often eat food, but lack autonomy with food decisions, with their parents controlling food purchases(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42) . The home environment also connects with the need for convenience among adolescents, where family meals are common and they can only eat the foods that have been bought for them(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13). Eating food with family usually means more structured meals and more health-promoting foods being eaten, whereas eating meals alone at home can be associated with more processed food consumption and less health-promoting eating habits such as eating while watching TV(Reference Rauber, Martins and Azeredo95,Reference Berge, MacLehose and Larson98,Reference Larson, Fulkerson and Story99) . Adolescents tend to follow their parents' eating habits, but many adolescents find their parents can lack nutritional knowledge and that the strict rules or restrictions parents place about eating can have both a positive and negative impact on their diet(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Fleary and Ettienne100) . Food rules in the home can provide some structure and guidance around adolescents' diets, for example only eating dessert at weekends can help them limit their consumption of less healthy foods(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Wang and Fielding-Singh101) . Such food rules can help adolescents learn positive eating habits and gain some autonomy about eating healthy foods(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Wang and Fielding-Singh101) . However, there is also a risk of negatively affecting adolescents' relationship with food, with restriction or the threat of punishment for breaking the rules furthering the dichotomy between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ foods(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13,Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42) . Adolescents often perceive a low level of control about their food choices at home(Reference Ziegler, Kasprzak and Mansouri13), but a recent study suggested using positive food choices as a way for adolescents to assert autonomy or independence from their parents(Reference Bryan, Yeager and Hinojosa33). Adolescents appear to like having guidance and structure around their diet, but it may be more beneficial for food rules to be positively oriented rather than restrictive in nature, so adolescents can know the benefits of and continue following these healthy habits throughout life.

Online food environment

The online environment can have a strong influence on adolescent food choice, usually resulting in less healthy food consumption(Reference Klassen, Douglass and Brennan83,Reference Qutteina, De Backer and Smits84,Reference Castronuovo, Guarnieri and Tiscornia102) . Particularly influential on adolescent food choice is the social media world, a relatively new form of media(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). Social media provides both information and influence, but the sources and quality of this online information are often poor and can affect consumption habits(Reference Klassen, Douglass and Brennan83,Reference Lynch85,Reference Pollard, Pulker and Meng103) . Research has shown that the quality of diet advice given online rarely matches evidence-based guidance(Reference Lynch85,Reference Sabbagh, Boyland and Hankey104) , and social media exposure in adolescents is linked with more body dissatisfaction, body image concerns and with more disordered eating habits(Reference Holland and Tiggemann49,Reference Klassen, Douglass and Brennan83,Reference Turner and Lefevre86) . The effect of seeing celebrities or peers with certain body ideals can make adolescents unsatisfied with their own body shape(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42). Such exposure can lead to social comparison and can change the perception of a healthy body. Adolescents have noted that social media tends to influence aspects of their diet and nutrition, providing opportunities to fall victim to unhealthy diet trends, with adolescents reporting that they often look up weight-loss tips online(Reference Fleming, Hockey and Schmeid42,Reference Klassen, Douglass and Brennan83,Reference Turner and Lefevre86) . As well as this connection to unhealthy eating habits, spending time on social media means adolescents are spending more time at screens, and higher levels of screen time in adolescents is linked with negative eating habits and health outcomes, such as higher intakes of less healthy, processed, snack foods(20,Reference Rauber, Martins and Azeredo95,Reference Robinson, Banda and Hale105) . Therefore, the online environment affects adolescent body satisfaction, their knowledge and understanding of good diet and nutrition practices, and their eating habits. While the effect of social media on body image is often negative, the influence peers and celebrities have could be harnessed for good through this ever-growing media world.

Conclusions

Much research on adolescent eating behaviours has focused on identifying the barriers to eating healthy foods and research to date has converged on the idea that several external aspects of price, availability and convenience within the food environment are central issues affecting adolescent food choice. However, it is also important to understand the specific motivations adolescents have towards healthy eating and the internal considerations that occur when making food choices, such as choosing foods based on the impact on their physical or social appearance. The principal factors that influence adolescent food choice are echoed around the world, independent of location, age or cultural background. Health is considered important for adolescents, but consistently taste, cost and convenience emerge as key influences on the food choices of adolescents. With relatively limited financial autonomy, adolescents often struggle to afford the more health-promoting foods, and in many circumstances, they do not have easy access to these foods even if they could afford them, due to limited availability within their food environment. It is much more common for cheaper, less healthy and better-tasting foods to be readily available to adolescents, even though they value the important role food and nutrition plays for their health. However, the role food plays in weight control and health can differ, so the importance adolescents place on short-term health or appearance and long-term health risk may affect their food choices. There are subtle but important differences in the barriers and facilitators for food choice in adolescents compared with younger children and adults, based on the level of independence, autonomy and skill they have about food, and the importance placed on health or weight control. The impact that food has on their health is important to adolescents, but only once practical elements of price, access and availability have been addressed, as well as taste preferences and social concerns about food. Social concerns for adolescents are variable depending on the context, but a common theme of body dissatisfaction and a desire to use food as a way to change their body shape is consistent worldwide. It is not as simple as increasing education on good nutrition, and improving the food environment for adolescents. It is also important to understand the specific social motivations for their food choices, and support them to be able to make health-promoting food choices the majority of the time without negatively affecting the social concerns relating to their peers and their bodies.

There is a need to improve the global and national situation on the increasing rates of overweight and obesity among adolescents, but it is also important to avoid the development of eating disorders or disordered eating habits in this impressionable age group. There are separate roles for improving the food environment in terms of access, availability and affordability, improving food in terms of taste and health content, and improving knowledge and skills to understand how to make healthy food choices, while understanding the balance between overeating, healthy eating and disordered eating. Promotion of a healthy diet through intuitive eating for health gain rather than restrictive eating for weight loss, along with adequate education and support surrounding nutrition and food might support a better relationship with food and a more positive health and weight status among adolescents and future adults in the population.

As adolescents gain more autonomy with their food choices, they need the skills to be able to prepare their own meals without over-relying on convenience snacks. Along with the school environment, there is a role at home for parents to support and give the freedom to adolescents to learn and practice preparing their own foods under guidance, so they have the skills and confidence to continue doing so as their level of independence and autonomy continues to increase into adulthood. The online social media environment about food is increasing in influence on adolescent food choice, as this is a source of nutrition information and social influence, but one that is, currently, poorly regulated and can have damaging effects on adolescents' food habits and their sense of self-esteem. There is a need to regulate the quality of nutrition information provided online to ensure this source of information and influence is not harmful to adolescents. There is also an opportunity for health promotion to use social media and digital platforms to encourage positive food choices in adolescents. There are key roles for both the school and home environment to encourage and promote healthy eating, by removing practical barriers and supporting better knowledge and skills for healthy eating, thereby making healthy food choices more accessible to adolescents. The influence of their peers and social networks is uniquely of high importance during adolescence.

It is important to get the balance right between health promotion for good health while remaining sensitive to practical, social and body image concerns in adolescents. Aside from providing basic nutrition, food is a source of physical, social and emotional enjoyment. The social side to food and eating is of particular importance for adolescents as they develop their independence and social status, so this needs to be understood better to improve adolescent nutrition and health. Policymakers and health promotors should aim to remove or minimise the impact of the barriers to healthy eating, and should capitalise on the facilitators as much as possible. Combining information on adolescent nutrition needs, their concerns for health and body image, and the barriers and motivations for healthy eating and food choice should support the development of more targeted and effective interventions in adolescent populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would such as to thank the Irish section of the Nutrition Society for inviting the present review paper as part of the postgraduate review competition.

Financial Support

This work was supported by funding from the Irish Department of Agriculture Food and the Marine.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

A.N.D. was involved in the generation of the review topic, data review and writing the review article. E.J.O.S. and J.M.K. advised on the content and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.