Internships in undergraduate education were deemed by George Kuh (Reference Kuh2008) and the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU) as one method in a list of “high-impact educational practices.” These practices support the AACU’s four student outcomes designed to move universities away from passive learning methods. Internships emphasize the fourth outcome, “integrative and applied learning,” (6) Footnote 1 by placing students in “real-world” worksites that allow engagement with concepts and skills acquired in the traditional classroom setting (see also Hynie et al. Reference Hynie2011). Among other high-impact instructional methods, including service learning and faculty-student collaborative research, an internship

brings one’s values and beliefs into awareness; it helps the students develop the ability to take the measure of events and actions and put them in perspective. As a result, students better understand themselves in relation to others and the larger world, and they acquire the intellectual tools and ethical grounding to act with confidence for the betterment of the human condition (Kuh Reference Kuh2008, 17).

An internship is the most frequently used high-impact method across all types of universities, (Kuh Reference Kuh2008,16) Footnote 2 yet it is more common and more developed in academic disciplines aligned closely with professions, such as nursing and hotel/restaurant management. These internships often are designed to result in job placement with the host company or organization. Footnote 3

The prospect of arranging internships for liberal arts students presents challenges. The host organizations may not identify a need for liberal arts interns, except perhaps as a generic administrative workforce. For their part, liberal arts departments may resist inclusion of career-based elements in their curricula; internships are a facet of “vocational education” and are the responsibility of the university’s career center, not the office of academic affairs (O’Neill 2010, 7–8).

PURSUING HIGH-IMPACT PRACTICE IN POLITICAL SCIENCE INTERNSHIPS

Political science students may engage with society’s “big problems” (e.g., poverty and injustice), and they seek intellectual enrichment linked to pragmatic skills of inquiry, research, and analysis that may empower them as problem solvers at least at a local level. A student’s sense of civic involvement and citizenship, if embraced in a curriculum, helps the program transcend the passive learning models targeted by high-impact educational practices. Individuals outside the discipline may presume automatically that political science produces “politically and civically engaged” graduates (Colby et al. Reference Colby, Beaumont, Ehrlich and Corngold2007, 25–43); therefore, they may be surprised that many political science programs instead focus on “the objective, often mathematically driven study of political institutions and behavior” (Colby et al. Reference Colby, Beaumont, Ehrlich and Corngold2007, 4). Regardless of the curricular priority of the program, an internship—by its nature—stimulates a student’s drive for political and civic engagement.

Two recent journal articles described high-quality political science internships. First, Pecorella (2007) maintained that a “work-learning contract” agreed to among the academic adviser, the student, and the onsite supervisor with scheduled midpoint and final evaluations will prevent students from being regarded as free or cheap labor for menial tasks. A high-quality experience will allow a student to be held to a high academic standard, integrating foundational scholarship (e.g., Kingdon’s (Reference Kingdon2010) policy-making models) in the assignments. Second, Hindmoor (2010, 485) listed at least seven advantages of political science internships to the program, including benefits to the student (e.g., useful experience, access to job opportunities, and improved GPA) and overall benefits for the program (e.g., “complement[ing] teaching in other courses”). Footnote 4 Writing about internships in Australia, Hindmoor echoed Pecorella’s assertion that experiential quality is built on a program’s formal contracts with the target institutions and organizations. Furthermore, a student gains the most from working on a “single project…of genuine interest to the host organisation” (Hindmoor Reference Hindmoor2010, 485). The underlying emphasis in both articles is on the depth of academic expectations rather than how student perspectives may be formed so that they “act with confidence for the betterment of the human condition” (Kuh Reference Kuh2008, 17). Therefore, a case for the high-impact nature of political science internships has not been deliberately made.

Yet, with fewer layers of hierarchy, small-city institutions directly expose students to decision-making processes and the impact of public policy.

FACING A “LOW-DENSITY OPPORTUNITY” ENVIRONMENT FOR INTERNSHIPS

Pecorella and Hindmoor both assume that an internship program has access to capital-city institutions. Universities located far from capitals or major metropolitan areas may tie into an already-established capital-city internship program; however, they more often must rely on local opportunities such as small-city administration, congressional district offices, regional or local offices of state or federal agencies, and any nonprofit organizations located in the area. Footnote 5 These “low-density opportunity” environments pose acute challenges for ensuring quality intern experiences, a quandary that is faced by the Mississippi University for Women (MUW). Located in Columbus, MUW is more than 100 miles from the state capital and metropolitan areas of any significance. The school enrollment of 2,600 consists mostly of commuter students, many of whom hold down at least one job, have children, or both. Mobility is constrained, especially for returning adult learners (i.e., older than age 24) who comprise about 40% of the MUW’s undergraduate enrollment (i.e., full- and part-time students combined). Most students intern locally in city halls and administrative departments as well as the few social service organizations in the area. Other than the Department of Human Services and Department of Corrections, few state agencies have offices in Columbus. Opportunities to intern at area federal offices (e.g., Columbus Air Force Base) are even less likely. Footnote 6

Because of personal commitments (e.g., working at a night job while they intern during the day), students who intern outside of Columbus usually prefer worksites in their hometown. Relatively few students can afford to seek the capital-city experience; much of it must be paid for out of pocket due to limited university resources; a fund for political science internships exists but the annual amount per student is significantly reduced if several students qualify.

Either three or six credits of internship (i.e., POL 490) may be taken toward the 36-credit political science degree. Three-credit internships require 120 hours onsite or 240 hours for the six-credit internship, the latter being a popular summer option.

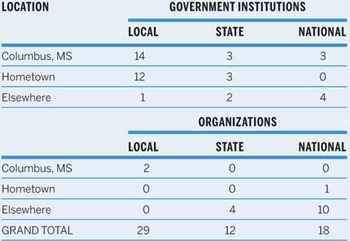

From 1999 to the present, 59 students—the majority being political science majors plus a few social sciences majors—have completed the POL 490 credits at MUW. Table 1 illustrates their internship worksite categories.

Table 1 POL 490 Internship Work Sites [N=59]

Since 2010, five MUW political science interns have been placed through formal programs such as The Washington Center (TWC) Footnote 7 and the Public Leadership Education Network. Of the other 54 placement opportunities, 38 (70.4%) were initially identified by the students themselves via personal connections (e.g., “The mayor of my town goes to my church”).

PURSUING HIGH-IMPACT PRACTICE IN A “LOW-DENSITY OPPORTUNITY” ENVIRONMENT

Small-town government administration provides students with responsibilities that include clerical tasks, which Colby et al. dismiss as offering “little potential to enhance [student] learning” (2007, 234). Yet, with fewer layers of hierarchy, small-city institutions directly expose students to decision-making processes and the impact of public policy. Only 15 of 59 MUW political science interns spent the balance of their time on a single institutional project, as Hindmoor (Reference Hindmoor2010) prefers. The projects include the drafting of bills for presentation in the US Congress or the Mississippi state legislature, writing grants, redesigning the city hall website, compiling material for regular public-affairs communications for a large government agency, producing web videos for lobbying and membership purposes, and helping to plan a statewide professional conference. Footnote 8

The other students who interned locally assumed a variety of duties, some more important than others but typically with daily administration tasks. Small-city institutions have low budgets, Footnote 9 are often staffed by fewer than a dozen people; and are willing to take on an intern only if (1) the student is unpaid, Footnote 10 and (2) the student can contribute to day-to-day operations. Onsite supervisors have been quick to promise that the student will participate in different components of the operation because help is needed in many areas. Preliminary negotiations with the site supervisor similar to the process that produces Pecorella’s written contract prevent the intern from being assigned menial tasks. Footnote 11

Thus, MUW political science internships are concerned with extracting as much valuable experience as possible from less-than-glamorous work arrangements, which is accomplished through the POL 490 assignments. Each student maintains a reflective occupational journal, which is submitted via Blackboard and worth 30% of the final grade. This document is a record of daily tasks, including the student’s reflection and assessment, and it helps the instructor to “monitor how students are doing in their placements, what they seem to be learning, and the kinds of issues each placement site tends to raise” (Colby et al. Reference Colby, Beaumont, Ehrlich and Corngold2007, 244). Another benefit of the journal is in helping students recall their own actions and reactions over time—which aid in completion of their analysis papers.

The proximity that interns in these arrangements have to decision makers and policy outcomes means that the worksite becomes a type of political and policy laboratory. What if the laboratory harbors harsh realities?

Toward the end of the term, students complete two intensive analysis papers, each six to seven pages long and submitted via Blackboard. These papers require the students to link concepts and relationships that they had studied so far in their political science classes with the human and institutional behavior at the worksite. By their nature, the concepts and relationships are slanted toward American politics and public administration. Footnote 12 Each paper is worth 35% of the final grade and generally structured as follows.

Paper 1: Understanding the Work Unit

The overall mission (i.e., guiding principles and goals pursued) of the work unit; leadership/management style; means by which power is communicated within the work unit; and relationships with other entities (i.e., horizontal and vertical).

Sample Question

Feminists see gender-driven influences in much of society. For this question, consider how well (or not) the [internship work unit] upholds feminist standards within its organization. Evaluate the accuracy for the [internship work unit] of the following three feminist organizational principles from Guy (Reference Guy, Timney Bailey and Mayer1992):

-

1. “Organizational hierarchies [are] less rigid.”

-

2. “Organizational climates [are] more cooperative, less competitive, and less aggressive.”

-

3. “Values of trust, openness, and acceptance . . . replace the quest for individual power.”

Paper 2: Opportunities for and Challenges to the Work Unit

Ability to seize opportunities and address challenges; ability to uphold rather than bend set procedures; pressure to accomplish more with fewer resources; and three recommendations for improvement of the unit.

Sample Question

Part of strategic management is developing a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis of all or some of an organization’s functions. Examples of SWOT analyses are in your public-administration textbook. For this question, assume that you have been asked to develop a SWOT analysis for the [internship work unit]. Include as many dimensions of organizational operations that you consider necessary to present a relatively complete picture of [the internship work unit’s] situation this year.

The proximity that interns in these arrangements have to decision makers and policy outcomes means that the worksite becomes a type of political and policy laboratory. What if the laboratory harbors harsh realities? Colby et al. recognized that some interns may have extreme emotional responses to human suffering related to certain worksites (e.g., a prison or a domestic-abuse shelter) and that they may become overly critical of government or social services institutions based on their experiences (2007, 246-8). The internship journals and analysis papers help to channel the students’ critique in a “safe” direction, preventing the internalization of frustrating or upsetting experiences. Furthermore, the analysis papers encourage a mindset of continuous improvement—not only to perceive a problem or challenge but also to find the underlying source and even to identify means by which it may be addressed. It is here that an internship may pursue most directly the qualities of high-impact educational practice.

HIGH-IMPACT LEARNING THROUGH CONSTRUCTIVE CRITIQUE IN ANALYSIS PAPERS

The evaluative abilities of MUW interns are stimulated by several questions for the analysis paper, including those listed previously. Table 2 categorizes responses to a question that requires students to play the role of an outside consultant who makes recommendations for improving the institution or organization. A total of 139 recommendations offered by 49 interns are classified in the table. Footnote 13

Table 2 Type of Recommendations Offered by 49 Interns [N=139]

Note: A small number of students offered fewer than the required number of recommendations, which is why the table classifies 139 recommendations rather than 147.

Three types of recommendations may be ruled out. First, budget and resource recommendations were mostly requests for higher appropriations and better equipment, such as new computers and police cars. Second, the small number of leadership-style recommendations often included commentaries on personalities. Third, recommendations regarding relations with the public and clients may warrant additional attention, but most were an appeal to make the work unit more accessible to outsiders or to improve public relations in general.

One goal of the MUW political science internship program is to encourage students to think critically of the institution’s operational philosophy. This helps them to clarify connections between resources and goals, people and politics, and ideals and reality. Many of the courses in the MUW political science major examine the intent to deliver and the capability of delivering public goods: whether an outcome as straightforward as “safe streets” or as complicated as economic policies intended to produce jobs in tomorrow’s industries. An initial review of the 139 recommendations in this study found only 12 that were explicitly related to the operational philosophy of the entity. Footnote 14 In a state with a troubled history of racial and social relations, it is not surprising that some students highlighted the need for justice and fairness, as illustrated in the following excerpts:

It is hard for even government officials to work together for the benefit of the town. For example, a letter to the editor was written…by a police officer who was black, and he talked about how saddened he was that this town cannot pull away from racism… He tells of how he cannot even trust those he works with because of this kind of discrimination… In order to improve the functioning of a government, the officials must work together as a team and trust one another to make honest decisions (Intern with a local government institution, 2006).

I don’t believe I will ever come around to the way of thinking that promotes low income taxes and associated high fees and other user taxes on everything. This mentality results in the provision of a massively lower level of services for citizens than I have encountered… I see the provision of a decent level of services as essential to the development of a healthy city. Without as much, there is an increasing divide within a community, and you are not growing a substantial segment of your community (Intern with a local government institution, 2006).

Do “low-density opportunity” environments produce significantly weaker experiences? Not at all. Students are exposed to a wide variety of experiences and are not sequestered in a single project that might restrict their overall perception of an institution.

The administrative aspect of the interns’ work afforded them a close view of the practical, Easton (Reference Easton1965)-inspired input/output nature of institutions (indeed, the students have emerged as careful studies of process and efficiency). Review of the 36 recommendations shows that many commented on matters closely related to underlying philosophies of operation. One student explained the following:

I am leery of city-county consolidation in many urban environments because of the great possibility of minimizing the political clout of more concentrated urban minority residents. In Mississippi as a whole and _____ County as well, however, those concerns are largely abated by the equally large percentage of minority residents out in the county… Consequently, greater government consolidation could save a great deal of resources and enable local governments to provide more services. (Intern with a local government institution, 2006)

Even a request to add personnel spoke to an element of operational philosophy:

[N]o one wants to help without being paid… However,…I think if we sent out a newsletter via email and Facebook, we would at least add some [volunteers] there at the office…, but [the director] seemed to have the mentality that until we get more funding through grants, we appear to be “stuck” without more help. (Intern with a nonprofit organization, 2010)

For other students, the need for a disciplined workforce resulted in recommendations that touched on a philosophy of operations—or a need for one:

The employees need to know how to conduct themselves in a professional manner, and I think an ethics seminar would influence them to do so. (Intern with a local government institution, 2011)

[A]ll city employees must be required to follow procedure…One city employee…had been making [unauthorized] purchases for the city…and there had been no consequences for her action. (Intern with a local government institution, 2009)

I cannot count the number of times I heard defendants complaining about never having spoken with their public defender prior to their court date… If a staff of people were to oversee their actions, then perhaps they would be more apt to inform their clients of their rights and to attend court sessions as planned. Otherwise, the judicial system is simply convicting people who in a sense never had a fair chance. (Intern with a local government institution, 2003)

CONCLUSION

Political science interns at universities in low-density opportunity settings typically do not have the ability to maintain capital-city internship arrangements such as those described by Pecorella and Hindmoor. My experience in supervising internships at MUW for more than 10 years has resulted in trying to make the best of the available situation; for their part, students have learned much from evaluating institutional productivity and integrity. Although by no means revolutionary, this avenue illustrates important dimensions of high-impact educational practice. Echoing Kuh’s assertion that an internship “brings one’s values and beliefs into awareness” (2008, 17), interns hone their perception of what makes good government, good policy, and good politics—not just a good evaluative skill but also a quality of good citizenship.

Do “low-density opportunity” environments produce significantly weaker experiences? Not at all. Students are exposed to a wide variety of experiences and are not sequestered in a single project that might restrict their overall perception of an institution. Likewise, the academic assignments require a close evaluation of structure, process, and outcomes, and they encourage students to uncover those underlying factors that inhibit the attainment of public and political goals. In maintaining focus on constructive critique, the interns are developing a mindset and an ability “to act with confidence for the betterment of the human condition” (Kuh Reference Kuh2008, 17).