“On July 14, [1965,] Johnson walked into a staff meeting, took a seat, listened for a while, and then told us, ‘Don’t let me interrupt. But there’s one thing you ought to know. Vietnam is like being in a plane without a parachute, when all the engines go out. If you jump, you’ll probably be killed, and if you stay in you’ll crash and probably burn. That’s what it is.’ Then, without waiting for a response, the tall slumped figure rose and left the room.

“If that’s how he feels, I thought as I watched the door close behind him, then why are we escalating the war; what’s the point if he thinks it’s hopeless? Maybe he’s going to end it. There was truth – rational truth – in what Johnson had said, a moment of illumination. Yet reflecting on the President’s startling statement, I realized that the seeming objectivity of his description also revealed the inward struggle: No matter what course he took, the result would be disaster, total and irrevocable. He was trapped; he was helpless – conclusions that were closer to his own fears than to external reality. Admittedly there was, by now, no easy way out. We had raised the stakes and increased our commitment; American boys were dead and American resources wasted. But still there were choices – to continue the unwinnable war, to withdraw, or to seek some kind of jerry-built compromise. These choices were all unpleasant, but they were not, equally, disasters of fatal magnitude.”

So writes Richard Goodwin, a White House aide and speechwriter under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, in his memoir Remembering America, which appeared three decades ago, made a modest splash, and then was quickly forgotten.Footnote 1 Goodwin’s anecdote serves as a useful way to begin this reexamination of the US military intervention in Vietnam, which was by far the largest and most consequential intervention in the Johnson years (the other being the Dominican Republic). For one thing, the account underscores a key point amply supported by the archival record and the tapes now available: that Johnson and his aides were not optimistic when they Americanized the war in 1965; they were gloomy realists who knew what they were getting into. The hubris so often ascribed to them – thanks in part to the influence of David Halberstam’s monumental, sprawling, brilliant work, The Best and the BrightestFootnote 2 – is seldom seen in that record, at least with respect to the long-term prospects in the fighting. Johnson, the evidence shows, experienced deep doubts not only about whether the war was winnable but whether the outcome really mattered to American national security. The anecdote also goes to the crucial question of presidential maneuverability and the related matter of periodization. Was Johnson really as trapped in mid-July as he told Goodwin and the other staffers? If the answer is yes, does this mean he was also trapped earlier in the year, in February–March, when the most important decisions for escalation were made? What is more, Goodwin usefully reminds us that the administration’s choices on Vietnam, though each of them lousy, were not of the same “fatal magnitude.”

Publicly, of course, Johnson offered a different Vietnam message that spring and summer. He depicted the intervention (the scope of which he sought to downplay) as necessary in national security terms, and as fulfilling a commitment made by three administrations to defend an allied government combating outside aggression. The struggle, he and his principal Vietnam advisors insisted, was part of the larger Cold War, necessary to halt the spread of Moscow- and Beijing-directed communism.

Birth of an Image

This was not a new message. American officials had always seen the Vietnam struggle through a Cold War lens, long before Lyndon Johnson entered the White House. Already in the late 1940s and early 1950s, during the French war against the Hồ Chí Minh-led Việt Minh, civilian as well as military analysts articulated an early version of the domino theory, linking the outcome in Indochina to a chain reaction of regional and global effects. Defeat in Vietnam, they warned, would have calamitous consequences not merely for that country but for the rest of Southeast Asia and perhaps beyond.

In early August 1953, for example, President Dwight D. Eisenhower told a Seattle audience: “If Indochina goes, several things happen right away. The Malayan peninsula, with its valuable tin and tungsten, would become indefensible, and India would be outflanked. Indonesia, with all its riches, would likely be lost too.” “So you see,” he continued, “somewhere along the line, this must be blocked. It must be blocked now. That is what the French are doing.” Consequently, continued American backing of the war effort mattered greatly; by assisting its close ally, Washington was acting “to prevent the occurrence of something that would be of the most terrible significance for the United States of America – our security, our power and ability to get certain things we need from the riches of the Indonesian territory, and from southeast Asia.”Footnote 3

When in early 1954 it began to appear that the French might soon lose the war, Admiral Arthur Radford, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), urged the commitment of US ground forces, and used the domino theory in support of his argument. He warned that if Indochina was lost, and the Western powers did nothing to prevent it, the loss of the rest of Southeast Asia would inevitably follow. Japan, the key to the United States’ defense posture in the region, could be expected to make an accommodation with the communist powers.Footnote 4 President Eisenhower, in a National Security Council (NSC) meeting on April 6, 1954, endorsed this view. According to the meeting’s note taker, the president said that “Indochina was the first in a row of dominoes. If it fell its neighbors would shortly thereafter fall with it, and where did the process end? If he was correct, said the president, it would end with the United States directly behind the 8-ball.”Footnote 5 The next day, Eisenhower gave his now-famous press conference where he publicly articulated this “domino theory”:

Finally, you have broader considerations that might follow what you would call the “falling domino” principle. You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly. So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences … [W]hen we come to the possible sequence of events, the loss of Indochina, of Burma, of Thailand, of the [Malay] Peninsula, and Indonesia following, now you begin to talk about areas that not only multiply the disadvantages that you would suffer through the loss of materials, sources of materials, but now you are talking about millions and millions of people.Footnote 6

After the French defeat later that year, the domino theory slid out of view for several years, as the communist insurgencies in various parts of Southeast Asia lost steam, and as Ngô Đình Diệm’s South Vietnam attained a measure of economic growth and (for a time) political stability. But the theory stood ready to be reasserted whenever some country in Asia seemed in danger of falling to communism. On January 19, 1961, on the eve of Kennedy’s inauguration, Eisenhower warned the new president that if Laos were lost it would only be “a question of time” before South Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and Burma were lost as well.Footnote 7 Later that fall, as the Kennedy team debated increasing the US commitment to South Vietnam’s defense, many top officials expressed the view that the fall of South Vietnam to communism would lead to the fairly swift extension of communist control, or at least accommodation to communism, in the rest of mainland Southeast Asia as well as in Indonesia. Or consider the breathtakingly sweeping prediction by General Lyman Lemnitzer, chairman of the JCS, in early 1962:

Of equal importance to the immediate losses [if South Vietnam were lost] are the eventualities which could follow the loss of the Southeast Asian mainland. All of the Indonesian archipelago could come under the domination and control of the USSR and would become a Communist base posing a threat against Australia and New Zealand. The Sino-Soviet Bloc would have control of the eastern access to the Indian Ocean. The Philippines and Japan could be pressured to assume, at best, a neutralist role, thus eliminating two of our major bases of defense in the Western Pacific. Our lines of defense then would be pulled north to Korea, Okinawa and Taiwan resulting in the subsequent overtaxing of our lines of communications in a limited war. India’s ability to remain neutral would be jeopardized and, as the Bloc meets success, its concurrent stepped-up activities to move into and control Africa can be expected … It is, in fact, a planned phase in the Communist timetable for world domination.Footnote 8

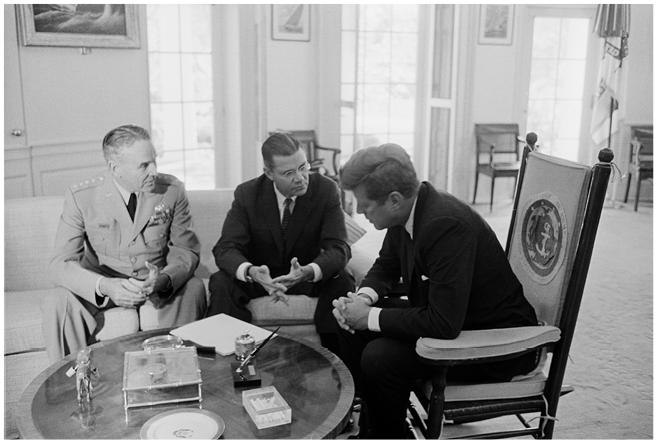

Figure 14.1 President John F. Kennedy (right) speaks with advisors, General Maxwell Taylor, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (left), and Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara (center) (August 23, 1963).

Kennedy himself never articulated the stakes in such grandiose terms, but he did on occasion endorse the domino theory, notably in September 1963 in an interview on NBC’s Huntley–Brinkley Report: “I believe it, I believe it.”Footnote 9 Other officials, too, in the critical years 1963–5, notably the Joint Chiefs of Staff, still articulated the theory in much the same way as before. So did Dean Rusk, now secretary of state but inclined to see things much as he had done a decade before. Lyndon Johnson, who assumed the presidency following Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, on occasion used domino imagery in talking about the choices in Vietnam. “We could pull out of there,” he declared in February 1964. “The dominoes would fall and that part of the world would go to the Communists. We could send our marines in there, and we could get tied down in a Third World War or another Korea action. The other alternative is to advise them and hope that they stand and fight.”Footnote 10

The Credibility Maxim

National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 288, approved by Johnson in March 1964, following a visit to South Vietnam by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, referred to dominoes in all but name in expanding US objectives in South Vietnam. No more would Washington merely seek to secure “an independent non-Communist South Vietnam”; henceforth, the whole of Southeast Asia must be defended. “Unless we can achieve this objective in South Vietnam,” the memorandum argued, “almost all of Southeast Asia will probably fall under Communist dominance (all of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), accommodate to Communism so as to remove effective US and anti-Communist influence (Burma), or fall under the domination of forces not now explicitly Communist but likely then to become so (Indonesia taking over Malaysia). Thailand might hold for a period without help, but would be under grave pressure. Even the Philippines would become shaky, and the threat to India on the West, Australia and New Zealand to the South, and Taiwan, Korea, and Japan to the North and East would be greatly increased.”Footnote 11

If NSAM 288 represented a kind of textbook articulation of the domino theory, it is nevertheless true that American thinking about the Cold War strategic stakes in Vietnam underwent an important shift in the Kennedy–Johnson era. In the documentary record, one sees less concern about the fall of Vietnam immediately leading to the fall of the rest of the region – the CIA, the Intelligence and Research desk (INR) at the State Department, and even numerous senior administration officials now concede that, as Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs William Bundy put it in October 1964, the original domino theory “is much too pat.” Or, as his brother McGeorge Bundy, national security advisor under both Kennedy and Johnson, asserted in a later interview: “[W]hat happens in one country affects what happens in another, yes, but that you could push one down and knock the rest over, its extreme form … I never believed that.”Footnote 12 A CIA report in June 1964 expressed doubts about the theory’s applicability to particular situations. True, the report said, the collapse of South Vietnam could cause neighboring Laos and Cambodia to fall as well. But it was only conjecture. And a “continuation of the spread of communism in the area would not be inexorable, and any spread which did take place would take time – time in which the total situation might change in any number of ways unfavorable to the communist cause.”Footnote 13

Instead, the worry now was less tangible, more amorphous, as US officials began to expound what Jonathan Schell has aptly called the “psychological domino theory.”Footnote 14 To be sure, from the start the domino theory had contained an important psychological component; now, however, that component became supreme. Credibility was the new watchword, as policymakers declared it essential to stand firm in Vietnam in order to demonstrate the United States’ determination to defend its vital interests not just in the region but around the world. Should the United States waver in Vietnam, friends both in Southeast Asia and elsewhere would doubt Washington’s commitment to their defense, and might succumb to enemy pressure even without a massive invasion by foreign communist forces – what political scientists refer to as a “bandwagon” effect. Adversaries, meanwhile, would be emboldened to challenge US interests worldwide.

Vietnam, in this way of thinking, was a “test case” of Washington’s willingness and ability to exert its power on the international stage. It was, in a sense, a global public relations exercise, in which a defeat anywhere in the world, even in comparatively small and remote (from an American perspective) places such as Indochina, could bring serious, even irreparable harm, to the United States’ geopolitical position. Even the incontrovertible evidence of a schism between the USSR and China, which affected the strategic balance in the Cold War in the mid-1960s in serious ways, seemingly did not lessen the importance of the credibility imperative. Beijing appeared to be the more hostile and aggressive of the two communist powers, the more deeply committed to global revolution, but the Soviets, too, supported Hanoi; any slackening in the American commitment to South Vietnam’s defense could cause an increase in Soviet adventurism. Conversely, if Washington stood firm and worked to ensure the survival of a noncommunist Saigon government, it could send a powerful message to Moscow and Beijing that indirect aggression could not succeed.

Again and again in the internal record, and in public pronouncements, one sees references to this psychological domino theory. In 1965 Johnson warned that “around the globe, from Berlin to Thailand, are people whose well-being rests, in part, on the belief that they can count on us if they are attacked. To leave Vietnam to its fate would shake the confidence of all these people in the value of America’s commitment, the value of America’s word.”Footnote 15 Early the following year, Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs John McNaughton put it this way: “The present US objective in Vietnam is to avoid humiliation. The reasons why we went into Vietnam to the present depth are varied; but they are now largely academic. Why we have not withdrawn is by all odds, one reason: to preserve our reputation as a guarantor, and thus to preserve our effectiveness in the rest of the world. We have not hung on (2) to save a friend, or (3) to deny the Communists the added acres and heads (because the dominoes don’t fall for that reason in this case), or even (4) to prove that ‘wars of national liberation’ won’t work (except as our reputation is involved).”Footnote 16 In short, according to McNaughton, maintaining American credibility was now the sole reason for the United States being in Vietnam.

Surely there was more to it than that, if not for McNaughton, then for other officials. Surely the desire to “save a friend” still belonged somewhere in the causal hierarchy, if not perhaps near the top. Dean Rusk certainly spoke in such terms on occasion, as did the president. Surely, too, some officials, notably members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, still adhered to the notion of falling dominoes in the original sense.

What is more, as I have argued elsewhere, a great many well-informed people, in Washington and elsewhere, rejected the notion that American credibility was on the line in Vietnam and that a setback there would inevitably cause similar losses elsewhere.Footnote 17 The skeptics were both numerous and influential, and included many top lawmakers on Capitol Hill (about which more below), mainstream newspapers around the country – including the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal – and prominent columnists. In the intelligence community, meanwhile, analysts at the CIA and INR in 1965 remained disinclined to put much stock on any kind of domino imagery.

The same was true abroad. Many Western governments, while not unsympathetic to what Washington sought to achieve in South Vietnam, emphasized the importance of nationalism and doubted that communism in one country meant communism in neighboring countries.Footnote 18 Some key allies, including the United Kingdom, did offer tepid rhetorical support for the Americanization of the war in 1965 (by which the United States took over from South Vietnam much of the conduct of the struggle), but Washington proved almost totally unsuccessful in gaining meaningful material support from friendly governments for the war effort. The Chinese and Soviet governments, meanwhile, backed the North Vietnamese, but both were anxious to avoid a direct military confrontation with the United States. Both were careful in this period to avoid making direct pledges of support to Hanoi in the event of large-scale American intervention. More important, it now seems quite clear, neither Moscow nor Beijing, nor most American allies, at the start of 1965 believed Washington’s global credibility would be crippled if it failed to stand firm in South Vietnam, particularly given the lack of broad popular support among Vietnamese for the Saigon regime.

None of this prevented top American policymakers from invoking, both publicly and privately, the credibility of American commitments in deciding for, and then justifying, the resort to large-scale war. They did so in the Johnson years, and they did so after the advent of the Nixon administration in 1969. Richard Nixon and his leading foreign policy advisor, Henry Kissinger, privately complained that their predecessors had chosen to make a major stand in Vietnam (disingenuously, in that both had been hawks in the key months of decision in 1964–5), but they too articulated the psychological domino theory in explaining their policy decisions. Said Kissinger in early 1969, with respect to Vietnam: “For what is involved now is the confidence in American promises … [O]ther nations can gear their actions to ours only if they can count on our steadiness.”Footnote 19

Second Thoughts

Yet these perceived Cold War imperatives cannot really explain the decision for major war in Vietnam, or the perpetuation of that war for eight long years. For one thing, the “other nations” to which Kissinger referred were not clamoring for Americanization in 1964–5; in the years thereafter, as the fighting intensified, most of them questioned not Washington’s credibility but its judgment. (Or, in the minds of some of them, US officials had forgotten that the two went together: credibility was not just about resolve, but also about judgment.) In domestic opinion, too, the thinking about the Cold War had begun to change by 1964, and the vaunted Cold War consensus to fracture – not following the Vietnam escalation, as is so often claimed, but before it. In the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis leaders in both Washington and Moscow reached the general decision that the Cold War must now be fought in a manner that would not bring about direct Soviet–American confrontation. Indeed, in 1963 much of the hostility drained out of the bilateral relationship. In June, Kennedy spoke at American University in conciliatory terms, urging cautious Soviet–American steps toward disarmament. More than that, he called on Americans to redefine some of their attitudes toward the USSR and toward communism, to “not to see conflict as inevitable, accommodation as impossible, and communication as nothing more than an exchange of threats.”Footnote 20 Then, in August, the adversaries defied the opposition of their respective bureaucracies to sign the Limited Test Ban Treaty, banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere, the oceans, and outer space. Individually these steps were small, but together they reversed the trend of the previous years and began to build much-needed mutual trust. Both superpowers began, after the missile crisis, to reconceptualize the Cold War, to think carefully about how they might wage it now that the option of general war was off the table.

This arguably meant, of course, waging the Cold War more aggressively in the Third World. Yet there is little evidence that senior US officials (who are the main concern here) thought in such terms, or that elite domestic opinion clamored for a more bellicose posture in the developing world.Footnote 21 On the right, the National Review condemned the American University speech and its call for reduced superpower tensions. Communism, the editors declared, was an “alien and inimical force bearing down upon the West,” something the president evidently did not understand. Some hawks in Congress, such as Senators Barry Goldwater (R-Arizona) and Strom Thurmond (R-South Carolina), thundered that Moscow would never keep its word and rejected JFK’s claim that the United States and the Soviet Union shared equally in creating Cold War suspicions. Senate minority leader Everett Dirksen (R-Illinois) wondered if the United States was “retreating from weakness rather than leading from strength,” both in Europe and in the rest of the world.Footnote 22

What is striking, however, is how few such condemnations were. Most leading newspapers and most news magazines welcomed the new initiatives, as did most legislators on Capitol Hill. A shift was under way. “It had become plain by the Summer of 1963,” influential columnist Walter Lippmann would write in November of the following year, “that the post-war period had ended.” It ended “with an uneasy and suspicious truce between the Soviet Union and the Western Alliance,” a truce that accepted the balance of power and reduced the tensions in the superpower relationship. Historian Jennifer W. See’s examination of elite and popular opinion in the months following the missile crisis finds a broad willingness to depart from the shibboleths of Cold War imperatives and “embrace a new perspective.”Footnote 23

Did this change have a significant potential bearing on the US commitment in Vietnam? The evidence suggests that it did. One can see it in the shift in the editorial position of many regional and national newspapers during 1963 and 1964 with respect to the Indochina struggle – not least the New York Times, which moved in fits and starts to a more dovish position, one that implicitly questioned Vietnam’s importance to American security. One can see it in Congress, where in late summer and early fall of 1963, as relations with the Ngô Đình Diệm government deteriorated, Kennedy administration representatives were subjected to tough questions not merely about the conduct of the war, but also about its viability and importance. Several centrist and left-of-center Senate Democrats – Albert Gore of Tennessee, Ernest Gruening of Alaska, Wayne Morse of Oregon, Frank Church of Idaho, and George McGovern of South Dakota, for example – cast considerable doubt on the long-term prospects of the war, and wondered whether the United States should not use the Diệm regime’s repressive policies as an excuse to get out of Vietnam. Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman J. William Fulbright (D-Arkansas) worried about the prospect of an open-ended commitment, as did Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-Montana), whose doubts had increased dramatically following a trip to Vietnam the previous year. When the administration that fall made public a plan to withdraw 1,000 advisors from Vietnam by the end of the year, an important rationale was the growing cognizance on the part of JFK and his aides that they would have to make a strong case to Congress for continuing US involvement. A partial withdrawal, so the argument went, would suggest to lawmakers that the current course was the correct one and that the administration did not plan for Americans to take over the main burden of fighting the war.

The misgivings among senators increased during 1964. More and more of them reached the conclusion that Vietnam was not worth the loss of American lives, that the outlook in the war effort was bleak, and that avenues of withdrawal should be actively sought. The group included the powerful trio of Mansfield, Fulbright, and Armed Services Committee chairman Richard Russell (D-Georgia) – the foreign policy leadership in the Senate – as well as several other Democrats and moderate Republicans. Publicly, to be sure, these and other skeptics kept largely silent. In August the vast majority of them voted for the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which gave LBJ broad authority to use military force in Southeast Asia. But this does not change the fact that a great many senior legislators were skeptical of the desirability of stepping up the US presence in the conflict (as even a cursory examination of the Congressional Record for August makes clear). John Sherman Cooper (R-Kentucky) spoke for many when during the debate over the resolution he cautioned on the Senate floor against a deepened US involvement in the war.

That fall, the Republican Party warned voters that, if they did not elect Barry Goldwater to the presidency, Vietnam would be “lost.” Americans in huge numbers took that chance. Goldwater was clobbered on Election Day, his belligerence on Vietnam as thoroughly repudiated as it could have been – Lyndon Johnson won forty-four states and 61 percent of the popular vote. True, Johnson did not campaign on the need for withdrawal from the conflict, nor did the electorate push for such a solution. But he got big cheers on the electoral trail when he vowed not to send American boys to fight Asian boys’ wars, and gave every indication that he was the candidate who would keep the nation out of large-scale war in Indochina. “We seek no wider war” was his steady refrain. This brings to mind comedian Mort Sahl’s joke, a staple of his club routine the following year: “My friends told me that if I didn’t vote for Lyndon Johnson in 1964, we would be bombing the North by the spring. And they were right. I didn’t vote for Johnson, and we were bombing the North by the spring.”

As Daniel Ellsberg notes in his extraordinary memoir Secrets, most Americans that autumn took Johnson at his word when he proclaimed that he sought “no wider war.” “It was what an overwhelming majority of them believed they were voting for on election day, November 3. No one I knew within the administration voted under that particular illusion. I don’t remember having time to vote that day myself, and I doubt [Assistant Secretary of Defense John] McNaughton did. We were both attending the first meeting at the State Department of an interagency working group addressing the best way to widen the war.”Footnote 24

Suppose Johnson had been up front with voters, and told them during the campaign what he and his advisors were privately coming to realize: that almost certainly the only real alternative to direct American combat involvement was either to negotiate a political settlement that would allow the United States to withdraw, or to await the imminent defeat or collapse of the Saigon government and the reunification of Vietnam under communist control. Suppose he then said that, on the basis of the cable traffic and intelligence data the government was receiving, he would seek a negotiated settlement leading to an eventual US withdrawal. It is not easy to believe that he would have lost against Goldwater in such a circumstance, given especially the drumbeat of pessimistic reporting in the press about the military situation and the incompetence and infighting of the South Vietnamese regime. Indeed, it is not easy to believe that he would have scored anything less than a decisive win.

Johnson did not go that route, of course, and it makes sense that he did not – in narrow political terms the savvy move was to keep Vietnam on the backburner during the campaign, which meant avoiding dramatic moves in either direction, toward escalation or withdrawal. Maintaining the present course was prudent. The point, however, is that there existed no all-powerful “Cold War Consensus” in American elite or popular opinion mandating an aggressive US posture in Vietnam. This was true before the election, and it was true afterward. Thus in December 1964 and January 1965, as South Vietnam seemed to teeter on the brink of collapse, many liberal and moderate lawmakers, including the entire Senate Democratic leadership, privately warned against any Americanization of the conflict and publicly predicted that a full-fledged congressional debate on Vietnam was imminent. White House opposition to such a debate and the unwillingness of lawmakers to force the issue kept one from taking place, but the private grumbling continued through March – by which point the pivotal decisions to commence sustained bombing and to dispatch the first ground forces had been made – and into the spring. Virtually all congressional skeptics were unwilling to say what they really believed: that Vietnam was not worth the price of a major war, that even the “loss” of South Vietnam would not have serious implications for American security; that a face-saving negotiated settlement was the best that could be hoped for. White House officials, all too aware of the widespread concerns on Capitol Hill, were relieved when no genuine debate on the war ever occurred in the first half of 1965. They had been particularly worried about the Senate, generally the more independent-minded of the two houses on foreign policy matters and in this case possessing leaders dubious about the commitment.Footnote 25

Clearly, then, severe trepidation about an American war in Vietnam on the part of senior members of Congress was fully formed well in advance of the key decisions of early 1965. Exact numbers are hard to come by, but it seems clear that in the Senate a majority were either downright opposed to Americanization or ambivalent about it; perhaps more important, the number of committed hawks that spring was remarkably small. (Congressional support would rise markedly in the summer, after Americanization had commenced in earnest, in a textbook example of the rally-round-the-flag effect.) It is misleading to suggest, as many authors do, that the war enjoyed broad support on Capitol Hill in the early years of large-scale war; in the key months of decision, the support was lukewarm at best. The dynamic changed only with the arrival in significant numbers of US combat troops in the spring and summer. At that point, Richard Russell believed, supporting the troops meant supporting the policy.

Nor were these misgivings expressed only about Vietnam. Top Democrats also grumbled about the rationale for another military intervention ordered by Johnson at this very time, this one closer to home, in the Dominican Republic. Here, military officers in 1963 had ousted leftwing but noncommunist Juan Bosch, the nation’s first elected leader since 1924. In April 1965 another group of military leaders tried to restore Bosch to power but were thwarted by the ruling junta. Announcing that “people trained outside the Dominican Republic” were seeking to gain control and that he would not allow “another Cuba,” Johnson sent nearly 23,000 troops to the country. Unfortunately for him, the CIA determined that no communists were involved. He ordered the FBI to “find me some Communists in the Dominican Republic,” and the US Embassy duly produced a weakly sourced list of fifty-eight (or fifty-three) “Communist and Castroite leaders” among the rebels.Footnote 26 The intervention put an end to the rebellion, but it outraged many Latin Americans. Fulbright, disturbed by what he saw as an evolving pattern of interventionism backed up by dubious “the-communists-are-taking-over” justifications, and perhaps feeling guilty for having failed to make his Vietnam misgivings public in a timely fashion, in the fall of 1965 charged the White House with following a policy of deception. Other critics concurred that Johnson was playing less than straight with the American people, and the term “credibility gap” entered the political lexicon.

The Costs of Getting Out

None of this is to suggest that disengagement would have been risk-free for Lyndon Johnson in domestic political terms. Such a course would have brought a cost, even if disguised through some kind of agreement leading to a coalition government in Saigon and a “decent interval” before any Hanoi takeover. The question is how big a cost. How many dominoes at home would have fallen? Cold Warriors would have branded him an “appeaser,” but in response he could have called on his own team of heavy-hitters to defend the decision. A distinction must be made, moreover, between being called names by your opponents and actually losing significant political power as a result. In view of the constellation of forces in Congress and in the press, especially after Johnson’s landslide election victory in 1964, there is little reason to believe that a decision against war would have exacted an exorbitant political price.

Nor do I find persuasive the claims by some authors that LBJ justifiably feared that his cherished Great Society program would have been scuttled by congressional hawks if he had opted against escalation. Dixiecrats and many Republicans, according to this view, would have banded together to filibuster the civil rights and social legislation if Johnson could have been made to appear soft on communism in Southeast Asia.Footnote 27 But who were these supposed hawks? How much clout did they have? And what exactly did they say, either publicly or behind closed doors, to support this line of argument? The proponents of this interpretation do not tell us. The evidence suggests strongly that Vietnam hawks in Congress were a small and timid lot in the spring of 1965 and, although their number and volubility might have grown later in the year had Johnson chosen to begin disengagement, it is hard to see how this would have changed the overall dynamic.

Moreover, if we are to speak of the price to be paid for getting out of Vietnam in 1965, we must also consider what cost Johnson could expect to incur if he opted for what by the early part of that year was the only genuine alternative: large-scale escalation. Numerous Johnson allies examined this cost in the winter and spring of 1965, and what they saw made them shudder. Many of them, it should be stressed, were seasoned political operators, shrewd tacticians with decades of electoral campaigning under their belt. They did not give recommendations that they believed would be, on balance and relative to the alternatives, bad for the Democratic Party.

Take Hubert Humphrey, vice president-elect and then vice president during the key period of decision-making. Writing privately to Johnson as one who saw his value to the president as “my ability to relate politics and policies,” Humphrey summarized his views of “the politics of Vietnam”:

It is always hard to cut losses. But the Johnson administration is in a stronger position to do so now than any administration in this century. Nineteen Sixty-Five is the year of minimum political risk for the Johnson administration. Indeed, it is the first year when we can face the Vietnam problem without being preoccupied with the political repercussions from the Republican right … The best possible outcome a year from now would be a Vietnam settlement which turns out to be better than was in the cards because the President’s political talents for the first time came to grips with a fateful world crisis and so successfully. It goes without saying that the subsequent domestic political benefits of such an outcome, and such a new dimension for the President, would be enormous.

Even if such a settlement did not result, Humphrey concluded, disengagement would still be far preferable to a risky escalation. “If, on the other hand, we find ourselves leading from frustration to escalation and end up short of a war with China but embroiled deeper in fighting in Vietnam over the next few months,” he wrote, “political opposition will steadily mount. It will underwrite all the negativism and disillusionment which we already have about foreign involvement generally – with direct spill-over effects politically for all the Democratic internationalist programs to which we are committed – AID [Agency for International Development], UN, disarmament, and activist world policies generally.”Footnote 28

A prescient analysis, time would show, but more than that it was one that would have won nods of approval at the time from the Senate Democratic leadership, from Democratic Party elder statesman Clark Clifford, and from leading voices in the American press. Furthermore, in considering Humphrey’s analysis, it is vitally important to bear in mind that no senior military analyst in the first half of 1965 offered the White House even a chance of swift military victory in Vietnam. Five years, 500,000 troops, was the general estimate Johnson heard. The war would be long and difficult, most everyone in a position of authority agreed, and would still be going as the campaigning began in 1968. Yet Johnson took the plunge, even though he shared many of Humphrey’s fears and even though there is no indication he received contrary advice from any equally authoritative political source.

Why he did so is something of a mystery. It is not, though, inexplicable. Part of the explanation, surely, is that escalation, if done quietly and without putting the nation on a full war footing, offered the path of least immediate resistance for the president. Given his and his advisors’ repeated public affirmations of South Vietnam’s importance to American security it made sense that they would be tempted to stand firm, in the hope – and hope is all it was – that the new military measures would succeed. Robert McNamara, McGeorge Bundy, Dean Rusk – all of them would have felt strong temptation to preach patience, to counsel staying the course. Their word, their reputations, their careers were on the line. Johnson’s was too. And he feared the personal humiliation he imagined would inevitably accompany a defeat (and in his eyes a negotiated disengagement constituted defeat).

On this point it is useful to return to the classic study by Doris Kearns, Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream. The book describes the president as being – notwithstanding his commanding and intimidating physical presence – deeply sensitive to fears and imagined accusations of being insufficiently manly. It is not impossible that this concern grew so large as to overwhelm calculations regarding electoral advantage.Footnote 29 Thus LBJ relayed to Kearns his fears about what Robert F. Kennedy would say about him if he got out of Vietnam, but he gives no sense that he ever faced the question of what RFK would do – including in terms of the nomination in 1968 – if he did not get out of Vietnam. In the same way, he appears to have thought little about whether the charges by hawkish critics would actually do lasting political damage to him; it mattered only that they might attack him.

Richard Goodwin, in Remembering America, goes down this line, describing his boss’s “increasingly irrational behavior” in the spring of 1965. In response, Goodwin writes, he consulted medical textbooks, talked to professional psychiatrists, and huddled with fellow White House aide Bill Moyers, who (according to Goodwin) fully shared his concerns. Based on their private and frequent interactions with Johnson, and their imperfect understanding as laymen, they each came to the belief that they were working for someone in the grip of clinical paranoia, a man who believed “the communists” (among them establishment journalists Walter Lippmann and Theodore White) and the Kennedys were out to get him. “As his defenses weakened,” Goodwin writes, “long-suppressed instincts broke through to assault the carefully developed skills and judgment of a lifetime. The attack was not completely successful. The man was too strong for that. Most of Johnson – the outer man, the spheres of rationally controlled thought and action – remained intact, most of the time. But in some ways and on increasingly frequent occasions, he began to exhibit behavior which manifested some internal dislocation.”Footnote 30

The tendency of historians to discount psychological interpretations of this kind is understandable, and defensible. Few of us, for one thing, have any training in such analysis. But on Vietnam 1964–5 these interpretations deserve more attention than they have received, because the leading alternative explanations do not stand up. This includes explanations pointing to threats to US security in the international system, which, though not absent in 1964–5, cannot account for Americanization. And it includes assessments emphasizing domestic political imperatives and the Cold War consensus. The keys to the major US military intervention in Vietnam are to be found not in the international arena nor in Vietnam, but at home in the United States. It was not, however, about meeting the demands of this supposed consensus, the power of which has been exaggerated. It was not even about domestic political advantage per se, at least not in the main. Lyndon Johnson, it seems, preferred to risk a revolt within his party, preferred to risk a contentious battle for the nomination in 1968, than to go into that campaign having been “weak” on Vietnam and having “allowed” defeat to occur there. And, in this respect, he succeeded. He withdrew from the presidential race on the last day of March 1968, the warnings of Hubert Humphrey having come true to an unerring degree. Some observers puzzled at the move, wondered if he was acting hastily and would come to regret dropping out (as indeed some part of him later did). But none of them called Johnson a quitter on Vietnam, and none questioned his manliness.