Introduction

Chronic, diet-related noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and several types of cancer are increasing worldwide, reflecting the vast and growing international burden of disease in this century, accounting for a significant proportion of global deaths and years of life lost.(Reference Roth, Abate and Abate1–3) At the same time, the consumption of foods prepared away from home (in restaurants, takeaway and home delivery establishments, cafeterias and snack bars, or as ready-to-eat retail products, for instance) is also rising.(Reference Fanzo and Davis4–Reference Smith, Ng and Popkin6) On the contrary, the time spent on preparing food at home is decreasing, particularly in high-income countries,(Reference Fanzo and Davis4–Reference Smith, Ng and Popkin6) mainly due to time scarcity(Reference Jabs and Devine7,Reference Venn and Strazdins8) . Changes in lifestyle associated with women’s expanded role in the paid workforce and an ever-increasing away-from-home food offer are likely driving both trends.(Reference Jabs, Devine and Bisogni9–Reference Hawkes11) The reconfiguration of cooking knowledge and skills and the social transformation of eating practices are equally noticeable, with the chores of the home kitchen being gradually replaced by the chores of shopping or driving for the next prepared meal.(Reference Cheng, Olsen and Southerton12,Reference Lang and Caraher13) In parallel, away-from-home food consumption has been identified as a risk factor for higher total energy and fat consumption and lower micronutrient intake,(Reference Lachat, Nago and Verstraeten14) as well as for becoming overweight.(Reference Nago, Lachat and Dossa15) Altogether, this highlights the role that cooking and eating more at home, at the expense of less away-from-home food consumption, could play in promoting better diet quality and health status.(Reference Fanzo and Davis4,Reference Lam and Adams16,Reference Mills, White and Brown17)

Most national food consumption surveys do not record or record but do not prioritise the analysis of data on how the foods reportedly eaten are procured, prepared, and/or served or who was mainly in charge of these activities, except to support more accurate assessments of food and nutrient intake.(Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams18,Reference Farfán, Genoni and Vakis19) A shortage of validated methods for classifying food intakes according to patterns of preparation compounds the problem further.(Reference Costa, Dekker and Beumer20,Reference Peltner and Thiele21) Related studies of the prevalence of different patterns of food preparation at the population level — as well as of their demographic and socio-economic drivers and potential impacts on nutrition and health status — are therefore scarce, being furthermore geographically limited and predominantly focused on adults.(Reference Smith, Ng and Popkin6,Reference Adams, Goffe and Brown22–Reference Choi, Kim and Yoon30) Further research on patterns of food preparation and associated factors in Europe is restricted to cohort studies(Reference Méjean, Lampuré and Si Hassen31–Reference Mills, Brown and Wrieden34) or analyses of national Time Use Survey data,(Reference Möser5,Reference Díaz-Méndez and García-Espejo35) with the notable exception of work using data from the North/South Ireland Food Consumption Survey 1997/99 to investigate associations between food preparation location and nutrient intakes in both adults and children.(Reference Burke, McCarthy and O’Neill36–Reference O’Dwyer, McCarthy and Burke38) Patterns of food preparation and their correlates have not yet been the object of extensive research in Portugal, apart from work reporting on the time adults dedicated to food preparation at home in a nationally representative sample in 2015,(Reference Perista, Cardoso and Brázia39) and a regional cohort study providing data on adult food intake location between 1999 and 2003.(Reference Naska, Katsoulis and Orfanos40–Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulos42)

Overall, these prior studies have shown that factors such as age, sex, and socio-economic status significantly influence eating habits, with notable differences in the frequency of consuming meals out and takeaway meals and in time spent on home food preparation.(Reference Nago, Lachat and Dossa15,Reference Adams, Goffe and Brown22,Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams24,Reference Méjean, Si Hassen and Gojard32,Reference Mills, Adams and Wrieden33,Reference Díaz-Méndez and García-Espejo35,Reference Perista, Cardoso and Brázia39,Reference Naska, Katsoulis and Orfanos40,Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulos42) They also have shown distinct national patterns in eating practices, with variations in nutrient intakes and diet quality depending on whether food is prepared at home or outside.(Reference Nago, Lachat and Dossa15,Reference Goffe, Rushton and White23,Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams24,Reference Wolfson and Bleich27–Reference Choi, Kim and Yoon30,Reference Mills, Brown and Wrieden34,Reference Burke, McCarthy and O’Neill36–Reference O’Dwyer, McCarthy and Burke38,Reference Naska, Katsoulis and Orfanos40–Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulos42) Therefore, based on the limited research on patterns of food preparation places, this cross-sectional study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of these patterns across the entire Portuguese population. Using data from the most recent National Food, Nutrition, and Physical Activity Survey (IAN-AF 2015/16), our study focuses on identifying patterns of food preparation in both children and adult diets. By uncovering demographic and socio-economic characteristics associated with these patterns, this study aims to better inform targeted public health strategies that promote healthier eating habits across various food preparation settings. Additionally, it is intended to explore the associations between patterns of food preparation and health and nutritional status, physical activity, and diet quality, offering valuable insights for public health policy and interventions.

Methods

Population and study sample

Participants in the IAN-AF 2015/16 (n = 6653) were randomly selected from the National Health Registry by multistage sampling and comprised a representative sample of the general (non-institutionalised) resident Portuguese population aged between 3 months and 84 years.(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43) This study analyses data from a sub-sample of survey participants aged between 3 years and 84 years, who completed two dietary intake assessments (n = 5005). Those who declined participation and completed a refusal questionnaire were generally older and less educated than participants, though differences in dietary consumption were minimal.(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43)

Dietary intake and diet quality

Dietary intake data were collected by trained researchers with a background in nutrition or dietetics, using an electronic platform (You eAT&Move) and following European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) recommendations for dietary assessment.(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43) Interviews 1–2 weeks apart were conducted over 12 months (from October 2015 to September 2016), distributed over the four seasons, and included all days of the week (randomly selected).(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43) Food consumption data were collected by two non-consecutive days of 24-h food diaries for children (<10 years) and two non-consecutive 24-h recalls for other age groups.(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43) Food photos for portion size estimation and automatic intake conversion using databases with the nutritional composition of foods and recipes were applied.(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43) For children, 24-h food diaries were followed by a face-to-face interview with the main caregiver, to gather details related to food description and quantification.(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43) For adolescents aged 10–14 years, 24-h recalls were administered with the presence of one of the caregivers; for adolescents aged 15–17 years, 24-h recalls were administered autonomously.(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43)

Dietary intake data were used to assess diet quality by calculating the Mediterranean Adequacy Index (MAI).(Reference Alberti, Fruttini and Fidanza44) The higher the MAI, the closer a diet is to the Healthy Reference National Mediterranean Diet, a healthful diet in which food patterns are inversely correlated with the prevalence of risk factors for NCDs. MAI terciles were therefore used to classify the quality of participants’ diet as low, medium, or high.

Demographic and socio-economic characteristics

Participants’ sex, date of birth, and parish of residence were drawn from the National Health Registry. Participants were grouped, according to age at date of first interview, into children (3–9 years), adolescents (10–17 years), adults (18–64 years), or older adults (65–84 years), and their parish of residence was classified as Predominantly Urban, Medium Urban, or Predominantly Rural according to the Portuguese National Institute of Statistics’ Classification of Urban Areas.(45)

Marital status, highest education completed, people living regularly in the household, and household monthly net income class were reported by adults and older adults only, during the first interview.(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43) Marital status was categorised as Not Married (single, widow/er, or divorced) or Married/Cohabiting, education as No Education/Primary Education, Secondary Education, or Tertiary Education, and household composition as Households without Children or Adolescents and Households with Children or Adolescents. Response options for household income class ranged from less than €485 to more than €4 365; answers were aggregated into three categories according to their dispersion: ≤ €970, €971–1 940, and >€1 940. For children and adolescents, the highest education level completed by their parents was reported and categorised similarly to that of adult and older adult participants.

A culturally adapted household food security questionnaire(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43,Reference Radimer, Olson and Campbell46) was administered to adults and older adults at the end of the second interview, and the results were used to classify the food insecurity status of their households as Food Security or Food Insecurity (mild and severe).

Health and nutritional status and physical activity

Data on indicators of health and nutritional status were collected for all participants. The prevalence of any disease requiring regular medical care (no/yes) was collected using a pre-defined list of NCDs.(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43) For participants aged 3–17 years, the list included asthma, diabetes, gastrointestinal disease, or other diseases. For participants aged 18 years and older, the list included heart disease, stroke, cancer, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, dyslipidaemia, gastrointestinal disease, depression, or other diseases. Body weight and height measurements were performed by trained researchers and participants classified into three classes of BMI — normal/underweight, overweight, or obesity — according to WHO standards.(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43,47)

Physical activity data were collected for all participants aged 15 years or above using the short version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ).(Reference Lopes, Torres and Oliveira43,Reference Craig, Marshall and Sjöström48) The present study analyses data on physical activity from adult and older adult participants only, with these being classified as Inactive, Minimally Active, or Active accordingly to the IPAQ guidelines for data processing and analysis.(49)

Classes of food preparation

The eAT24 module(Reference Goios, Severo and Lloyd50) of the IAN-AF data collection platform enabled interviewers to apply the EFSA FoodEx2 classification system(51,52) to classify reported food intakes into three facets — foods, composite dishes/recipes, or food supplements — and corresponding descriptors, as applicable. A category of descriptors indicating the immediate food source (F22) or composite dish/recipe source (RF22) of a registered intake — titled Preparation/Production/Acquisition Place — was employed in the present study to reclassify intakes according to preparation locations. Table 1 and Figure 1 depict the steps and outcomes of this reclassification process, the development of which was informed by previous similar studies.(Reference Costa, Dekker and Beumer20,Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams24) Registered food intakes were reclassified by the first author and an expert reviewer independently, and resulting discrepancies were solved by a senior author.

Table 1. Classification of foods or beverages intakes of IAN-AF 2015/16 participants according to the classes of food preparation

Figure 1. Decision diagram aiding in the classification of foods or beverages intakes of IAN-AF 2015/16 participants according to the classes of food preparation.

Statistical analysis

Mean daily intakes (%) of foods and beverages were calculated from the average food consumption (grams of edible weight) of each meal component recorded in the dietary assessments, for each class of food preparation considered. Values obtained for the class Away from home, not specified were negligible and hence excluded from further analysis. The remainder underwent hierarchical cluster analysis to uncover patterns of food preparation, using the Ward’s minimum variance method for agglomerating dissimilarities.(Reference Ward53) The resulting cluster tree was trimmed from three to seven clusters, and a final four-cluster solution was achieved based on Dunn index values.(Reference Ward53)

The distribution of the patterns of food preparation (%) uncovered by cluster analysis was cross tabulated with the distributions (%) of the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of interest (sex, age group, degree of urbanisation of residence area, completed education, marital status, household composition, household monthly net income, household food insecurity status), health and nutritional status (NCDs, BMI), level of physical activity (IPAQ), and diet quality (MAI). The intakes of children and adolescents corresponding to a pattern of food preparation At home by themselves were negligible (<0.5%) and were therefore concatenated with the intakes corresponding to a pattern of food preparation At home by relatives or friends, to form an overall pattern of food preparation At home. In view of this, the number of food preparation patterns identified for adults/older adults and children/adolescents differed, leading to the performance of subsequent analyses independently for these two groups of participants.

Associations between demographic and socio-economic characteristics and patterns of food preparation were analysed by estimating logistic regression models, to obtain crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR and respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The patterns of food preparation At home by themselves and At home were the reference categories in the case of adults/older adults and children/adolescents, respectively. Covariates were selected based on prior literature, theoretical considerations, and their potential to confound the relationships under study. Final models were adjusted for sex, age group, degree of urbanisation of residence area, or education, as applicable.

Logistic regression models were equally used to study the association between patterns of food preparation and the prevalence of NCDs (no vs. yes), nutritional status (normal/underweight vs. overweight and obesity), level of physical activity (active and minimally active vs inactive), and MAI (medium and high vs. low). Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were also obtained, and the final models adjusted for total energy intake, sex, age group, degree of urbanisation of residence area, or education, as applicable.

All statistics were performed by the R Software version 3.6.3,(54) and the sample was weighted for the Portuguese population distribution, using library ‘survey’.(Reference Lumley55) A significance level of α = 0.05 was considered in all analyses.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Commission for Data Protection, the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Public Health of the University of Porto, and the Ethical Commissions of each of the Regional Administration of Health. All participants were also asked to provide their written informed consent for participation according to the Ethical Principles for Medical Research involving human subjects expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki and the national legislation. Written agreements from the legal representative were required for children and adolescents below 18 years, and adolescents were also asked to sign the consent form together with their legal representative.

Results

Dietary intake per class of food preparation

The foods and beverages consumed daily by Portuguese residents are predominantly prepared (or acquired, in the case of those consumed in natura) away from home, namely, at food retail establishments (45.8%, 95%CI = 44.8, 46.9%). Another important share of their diets (18.6%, 95%CI = 17.6, 19.5%) is prepared at home, but not by themselves. Self-prepared foods and beverages at home represent only slightly over 10% of mean daily intakes (12.2%, 95%CI = 11.2, 13.3%); all other food preparation classes represent less than 9%. Table S1 in Supplementary Materials shows the distribution of mean daily intakes (%) per class of food preparation.

Patterns of food preparation

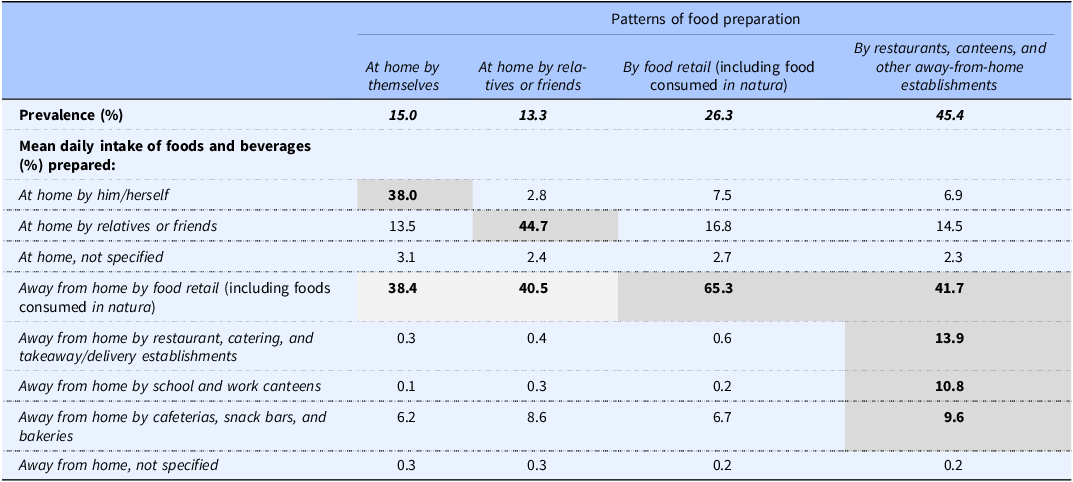

Cluster analysis identified four distinct patterns of food preparation among Portuguese residents (Table 2). The most prevalent pattern (followed by 45.4% of the participants) is characterised by the highest proportions of intakes of foods and beverages prepared by restaurants (13.9%), canteens (10.8%), and other foodservice establishments (9.6%) and is hence labelled By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments. Specifically, about a third of the diet of individuals in this pattern is prepared away from home by foodservice operators. The second most prevalent (followed by 26.3% of the participants) exhibits the highest proportion — nearly two-thirds — of intakes of foods and beverages prepared by or acquired from food retail operators (including those consumed in natura) (65.3%); it is therefore named By food retail. The second least prevalent pattern (followed by 15.0% of the participants) distinguishes itself by having the highest proportion of intakes from foods and beverages prepared at home by individuals (38.0%) and is hence labelled At home by themselves. The least prevalent one (followed by 13.3% of the participants) displays the highest proportion of intakes from foods and beverages prepared at home by relatives or friends of individuals (44.7%); it is thus named At home by relatives or friends.

Table 2. Patterns of food preparation identified for the Portuguese population using hierarchical cluster analysis (n = 5005; 3–84 years)

Tables S2 and S3 in Supplementary Materials show the distributions of the patterns of food preparation by the classes of demographic and socio-economic characteristics, health and nutritional status, level of physical activity, and diet quality considered.

Demographic and socio-economic characteristics

Children and adolescents

Table 3 depicts the associations between demographic and socio-economic variables and patterns of food preparation among children and adolescents, taking the pattern of preparation At home as an outcome reference. Results adjusted for sex, area of residence, and parental education show that adolescents have lower odds of being classified in patterns characterised by high away-from-home food preparation than children: By food retail (OR = 0.32, 95%CI = 0.20, 0.53) and By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments (OR = 0.29, 95%CI = 0.17, 0.49). Meanwhile, all non-adults living in medium urban areas have lower odds of being classified in the pattern of food preparation By food retail than those living in predominantly urban areas (OR = 0.42, 95%CI = 0.19, 0.91). No significant associations between patterns of food preparation and sex or parental education are observed.

Table 3. Association between demographic and socio-economic characteristics and patterns of food preparation, among children and adolescents (n = 1153; 3–17 years), weighted for the distribution of the Portuguese population

* Outcome reference is food preparation pattern At home.

† Model adjusted for sex, age group, area of residence, and education completed by parents.

‡ Education completed by parents.

Adults and older adults

Table 4 depicts the associations between demographic and socio-economic variables and patterns of food preparation among adults and older adults in Portugal, taking the pattern of food preparation At home by themselves as outcome reference, before and after adjusting for sex, age group, area of residence, and education as appropriate. Results show that, irrespectively of age group, adult men have higher odds of being classified in patterns characterised by high intakes of food prepared by others when compared to women: At home by relatives or friends (OR = 11.60, 95%CI = 7.58, 17.75), By food retail (OR = 2.05, 95%CI = 1.58, 2.66), and By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments (OR = 4.20, 95%CI = 3.17, 5.57). On the other hand, compared to younger adults, older adults have lower odds of being classified in patterns of food preparation At home by relatives or friends (OR = 0.57, 95%CI = 0.37, 0.89) and By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments (OR = 0.37, 95%CI = 0.26, 0.53), but not By food retail (OR = 0.90, 95%CI = 0.64, 1.26). Furthermore, all adults living in predominantly rural areas have lower odds of falling in the pattern of food preparation By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments than those living in predominantly urban ones (OR = 0.58, 95%CI = 0.38, 0.88). Conversely, all adults living in households with children or adolescents have higher odds of falling in this pattern (OR = 1.52, 95%CI = 1.10, 2.11).

Table 4. Association between demographic and socio-economic characteristics and patterns of food preparation, among adults and older adults (n = 3852; 18–84 years), weighted for the distribution of the Portuguese population

* Outcome reference is food preparation pattern At home by themselves.

† Models adjusted for sex, age group, area of residence, and education, except for household monthly net income, where it was adjusted for sex, age group, and area of residence only.

Findings in Table 4 also reveal that, irrespectively of age group, adults with secondary or tertiary education have higher odds of being classified in patterns characterised by high intakes of food prepared by others than those completing none or primary education only: At home by relatives or friends (secondary: OR = 2.32, 95%CI = 1.55, 3.47; tertiary: OR = 2.31, 95%CI = 1.31, 4.10), By food retail (secondary: OR = 2.58, 95%CI = 1.85, 3.59; tertiary: OR = 2.85, 95%CI = 1.79, 4.53), and By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments (secondary: OR = 3.29, 95%CI = 2.27, 4.76; tertiary: OR = 5.48, 95%CI = 3.59, 8.37). Likewise, adults from households with a monthly net income higher than €970 have higher odds of falling in these patterns than those in a lower income range: At home by relatives or friends (€971–1940: OR=1.83, 95%CI = 1.18, 2.82; >€1940: OR = 2.13, 95%CI = 1.25, 3.60), By food retail (€971–1940: OR = 2.15, 95%CI = 1.55, 2.99; > €1940: OR = 3.60, 95%CI = 2.14, 6.05), and By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments (€971–1940: OR = 2.45, 95%CI = 1.81, 3.31; >€1940: OR = 4.59, 95%CI = 2.99, 7.04). On the other hand, all adults from food-insecure households have lower odds of being classified in these patterns than the remainder: At home by relatives or friends (OR = 0.43, 95%CI = 0.27, 0.69), By food retail (OR = 0.63, 95%CI = 0.42, 0.95), and By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments (OR = 0.53, 95%CI = 0.34, 0.82). No significant associations between patterns of food preparation and marital status are found after adjustment for other variables.

Health and nutritional status, physical activity, and diet quality

Children and adolescents

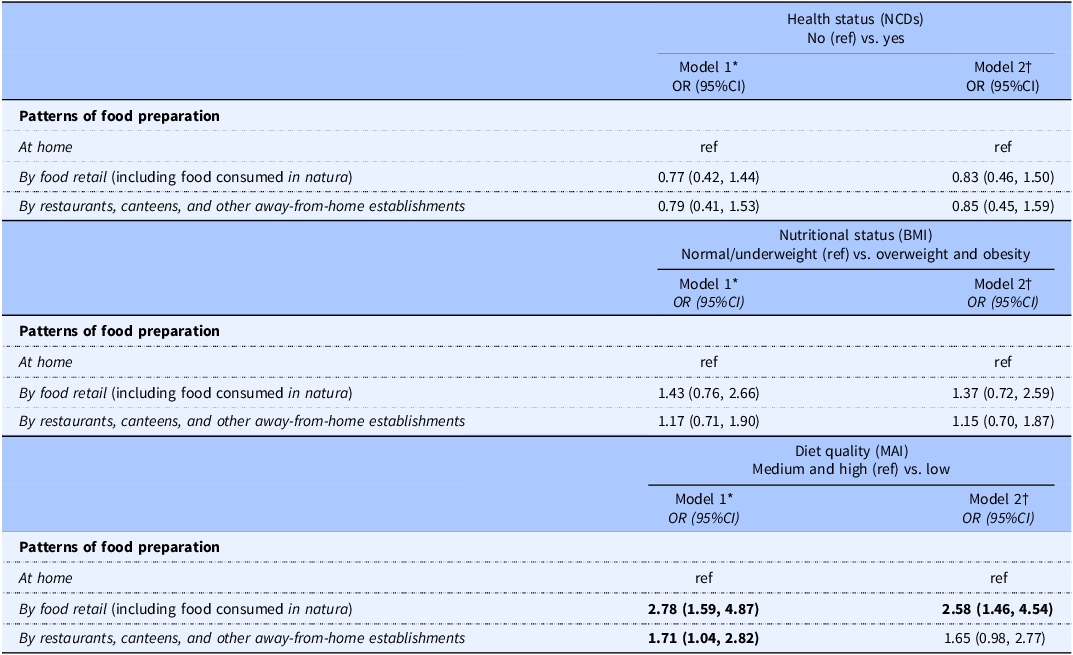

Table 5 shows the associations between patterns of food preparation among children and adolescents and their health and nutritional status, as well as diet quality. No significant associations are observed between the patterns and the prevalence of NCDs or overweight/obesity. Notwithstanding, children and adolescents falling in the pattern of preparation By food retail exhibit higher odds of having a low diet quality (OR = 2.58, 95%CI = 1.46, 4.54) than those falling in the pattern of preparation At home.

Table 5. Association between patterns of food preparation and health and nutritional status and diet quality, among children and adolescents (n = 1153; 3–17 years), weighted for the distribution of the Portuguese population

NCDs, noncommunicable diseases; MAI, Mediterranean Adequacy Index.

* Adjusted for total energy intake.

† Adjusted for total energy intake, sex, age group, area of residence, and education completed by parents.

Adults and older adults

Table 6 shows the associations between the patterns of food preparation among adults and older adults and their health and nutritional status, level of physical activity, and diet quality. No associations between patterns of food preparation and the prevalence of NCDs remain after controlling for sex, age group, area of residence, and education. Yet, adults and older adults falling in the pattern of preparation By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments present lower odds of overweight/obesity (OR = 0.74, 95%CI = 0.56, 0.97) than those falling in the pattern of preparation At home by themselves.

Table 6. Association between patterns of food preparation and health and nutritional status, level of physical activity, and diet quality, among adults and older adults (n = 3852; 18–84 years), weighted for the distribution of the Portuguese population

NCDs, noncommunicable diseases; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; MAI, Mediterranean Adequacy Index.

* Adjusted for total energy intake.

† Adjusted for total energy intake, sex, age group, area of residence, and education.

Findings in Table 6 also uncover that adults and older adults falling in the patterns of preparation At home by relatives or friends (OR = 1.84, 95%CI = 1.32, 2.57) or By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments (OR = 1.45, 95%CI = 1.08, 1.96) have higher odds of reporting low physical activity than those falling in the pattern of preparation At home by themselves. Moreover, adults and older adults falling in patterns characterised by high intakes of foods prepared by others show higher odds of having low diet quality (At home by relatives or friends: OR = 2.03, 95%CI = 1.25, 3.31; By food retail: OR = 3.59, 95%CI = 2.36, 5.45; By restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments: OR = 3.01, 95%CI = 2.08, 4.34).

Discussion

Studies investigating the prevalence of at-home versus away-from-home patterns of food preparation at population level remain scarce, particularly those drawing from the results of dietary intake assessments of nationally representative samples encompassing individuals of all ages.(Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams24,Reference Burke, McCarthy and O’Neill36–Reference O’Dwyer, McCarthy and Burke38) This prevents the development of a better understanding of the factors driving the consumption of food prepared at home versus away from home, as well as of related effects on nutrition and health. The present work contributes to close this gap by performing a cross-sectional analysis of food intake data drawn from IAN-AF 2015/16 to identify patterns of food preparation for both children and adults in Portugal and uncover their associations with demographic and socio-economic characteristics, health and nutritional status, level of physical activity, and diet quality. Our main results indicate that the most common pattern of food preparation involves a high intake of foods and beverages prepared by foodservice establishments as restaurants and canteens. They also indicate that higher socio-economic status is linked to greater reliance on foods prepared away from home, which impacts on a poorer diet quality and a more sedentary lifestyle, but not necessarily on higher obesity rates or NCDs. These findings support the need for tailored public health strategies that consider the most vulnerable groups, and provide valuable insights for developing more effective public policies aimed at increasing access to healthy food options in foodservice establishments as well as promoting more active lifestyles among people less likely to cook at home.

Patterns of food preparation

Regarding food preparation patterns, the findings of this study indicate that nearly three-quarters (71.7%) of Portuguese residents eat foods and beverages prepared and/or procured mainly away from home, that is, originating from the foodservice or the food processing and retail sectors rather than prepared at home. Indeed, household expenditure data place the share of away-from-home food spending in Portugal at 10.6% in 2022, well above the European Union average of 6.7%.(56) Despite Portugal’s disposable income per capita being lower than the European Union average, work schedules, better weather conditions, and cultural preferences for dining out, together with the increasing availability and convenience of foodservice options may contribute to the Portuguese higher spending on food away from home. A comparable analysis of adult food intake data from the United Kingdom National Diet and Nutrition Survey 2008/16 reveals the consumption of food prepared at home to be low.(Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams24) On the contrary, analyses of adult intakes from the North/South Ireland Food Consumption Survey 1997/99,(Reference O’Dwyer, Gibney and Burke37) the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2003/04 and 2007/08,(Reference Smith, Ng and Popkin6) the Republic of Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007/09,(Reference Lee, Song and Cho29) as well as of intakes from the Republic of Ireland National Children’s Food Survey 2003/04,(Reference Burke, McCarthy and O’Neill36) indicate that the consumption of food prepared at home is largely prevalent in these regions. Aside from variation in food preferences and habits attributable to culture, such disparity in extant findings likely stems from underlying methodological differences in the timeframe, sampling, age group, dietary assessment protocol, and food intake classification applied.(Reference Bezerra, Curioni and Sichieri57,Reference Wellard-Cole, Davies and Allman-Farinelli58)

Demographic and socio-economic characteristics

Respecting individual demographic characteristics, the results of this study show that adult men are less likely than women to consume foods prepared at home by themselves, underscoring their traditional lower involvement in domestic cooking and suggesting a possibly higher reliance on others for food preparation and supply.(Reference Cerrato and Cifre59) Adult men are also found to consume less home-prepared food than women in the United Kingdom, albeit the difference here being small.(Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams24) Similarly, adult men have lower odds to eat meals prepared at home than women in the Republic of Korea.(Reference Lee, Song and Cho29,Reference Choi, Kim and Yoon30) Meanwhile, in the present study, adolescents are more likely than children to consume foods prepared at home by themselves, relatives, or friends. Being more autonomous and independent than younger children, adolescents may more often leave school and return home at noon to eat a cooked lunch, rather than doing so in school premises.(Reference Cordovil, Lopes and Neto60,Reference Marzi and Reimers61) This might explain why they eat relatively more food prepared at home. In the Republic of Ireland, where a cooked lunch is generally not provided at primary schools, older children (9–12 years) are found to be more likely to eat food prepared away from home than younger children (5–8 years), particularly products acquired from food retail and takeaway outlets.(Reference Burke, McCarthy and O’Neill36) Furthermore, older adults in the present study are less likely to consume foods prepared at home by relatives or friends or prepared at restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments, than other adults, indicating a likely higher involvement in grocery shopping and domestic food preparation activities. Lower time and effort demands from work-related activities and the loss of income that accompany ageing and retirement probably explain why older adults resort more often to food prepared at home.(Reference Crompton and Lyonette62) For instance, younger adults tend to consume more commercially prepared meals than older adults in the Republic of Korea.(Reference Choi, Kim and Yoon30) Nevertheless, the consumption of home-prepared food by older adults in the United Kingdom is found to be similar to that of younger adults.(Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams24) Lastly, although married/cohabiting adults are found to have higher odds of eating meals prepared at home than unmarried ones in the Republic of Korea,(Reference Lee, Song and Cho29,Reference Choi, Kim and Yoon30) no associations between marital status and patterns of food preparation are observed in the present study.

Regarding household demographics, findings show that adults and older adults living in predominantly rural areas, as well as children and adolescents living in medium urban areas, are less likely to consume foods prepared away from home (by foodservice and food retail, respectively) than those living in predominantly urban areas. In line with this, European adults with the highest access to restaurants and medium access to grocery stores, both typical of predominantly urban areas, are shown to have the lowest likelihood of preparing meals at home daily.(Reference Pinho, Mackenbach and Charreire63) Moreover, the adults and older adults in the present study who live in households with children or adolescents are more likely to consume food prepared by restaurants, canteens, and other away-from-home establishments than the remainder. Similarly, results from the US Department of Agriculture’s 2012/13 National Household Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey show that the presence of children (<18 years) in households increases their expenditures in fast-food and full-service restaurants.(Reference Saksena, Okrent and Anekwe64) The food provisioning strategies of contemporary families may be a relevant explanation for the higher consumption of meals from out-of-home sources by households with children or adolescents. In particular, the purchase of convenience foods and ready-to-eat meals may be favoured as the consumption of such products typically lowers preparation, cooking, and kitchen clean-up times.(Reference Carrigan, Szmigin and Leek65)

With respect to socio-economic variables, the adults and older adults with higher education or from households with higher income in this study are more likely to consume food prepared away from home than the remainder, whereas the opposite is true for those living in food-insecure households. High-income adults in the United States,(Reference Smith, Ng and Popkin6) as well as adults who are employed, more educated, and of a higher economic status in the Republic of Korea,(Reference Lee, Song and Cho29,Reference Choi, Kim and Yoon30) equally tend to consume less food from home sources. Conversely, university-graduated adults in the United Kingdom tend to eat slightly more home-prepared food.(Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams24) All evidence considered, the balance between at-home and away-from-home food consumption is likely to constitute a fairly good indicator of the type and rate of socio-economic development of regions and countries; the distribution of income, labour, time, and expense within and between households; and the prevalence of gender and social inequalities in societies.(Reference Virudachalam, Long and Harhay26,Reference Adams, Goffe and Adamson66)

Health and nutritional status, physical activity, and diet quality

Concerning nutritional and health status, the results of this study indicate that adults and older adults with higher consumption of food prepared by restaurants and other foodservice establishments are less likely to be overweight or obese than those more reliant on the food they prepare at home themselves. There are further no associations between food preparation patterns and weight or health status after adjustment for total energy intake, sex, age group, area of residence, and education. Extant systematic reviews and meta-analyses generally conclude for the existence of a positive link between the consumption of food away-from-home consumption and markers of NCDs, particularly BMI.(Reference Nago, Lachat and Dossa15,Reference Bezerra, Curioni and Sichieri57,Reference Godbharle, Jeyakumar and Giri67) However, they also highlight that high variation as well as important limitations in how associations between eating out, diet quality, and nutritional status are typically studied weaken such conclusion,(Reference Mancino, Todd and Lin68) with several cross-sectional and prospective cohort studies finding no or negative associations.(Reference Bezerra, Curioni and Sichieri57,Reference Wellard-Cole, Davies and Allman-Farinelli58,Reference Godbharle, Jeyakumar and Giri67) On the other hand, cohort studies conducted in the United States and the United Kingdom suggest there is a preventive effect of increasing the frequency of consumption of homecooked meals, at the expense of eating out, on the risk of overweight, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, likely to be mediated by an improvement of diet quality.(Reference Mills, Brown and Wrieden34,Reference Taillie and Poti69,Reference Zong, Eisenberg and Hu70) Findings from the present study, as well as from a French prospective cohort,(Reference Méjean, Lampuré and Si Hassen31) do not support these hypotheses, however. Furthermore, several studies point out that the protective effects of increasing engagement in meal preparation activities at home on diet and health may be higher for household members than caregivers themselves.(Reference De Ridder, Lebacq and Ost71–Reference Chu, Addo and Perry74) Meanwhile, aspects related to disposable income and lifecycle, such as household income class, size and composition, and engagement in the workforce are likely important moderators of the effects of food preparation and consumption practices on diet quality and BMI.(Reference Choi, Kim and Yoon75–Reference Crespo-Bellido, Grutzmacher and Takata77) Beyond the regression analyses conducted in the present study, future studies should address the roles played by the aforementioned mediating and moderating factors.

With respect to lifestyle factors, the present study shows that, irrespectively of age group, individuals with a high intake of food they do not prepare themselves (i.e. meals prepared at home by relatives or friends or away-from-home by restaurants, canteens, and other foodservice establishments) are less likely to adhere to the Mediterranean diet and more likely to report low physical activity. Somewhat in line with this, adherence to DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stopping Hypertension) in the United Kingdom is linked to higher consumption of homecooked food among adults.(Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams24) Noticeably, a previous pan-European study has also found evidence of a positive association between eating out of home and sedentarism.(Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulos42) An important gap in research relating food preparation and consumption practices with physical activity remains, nonetheless, as most studies so far look exclusively at associations with diet quality and nutritional status.(Reference Mills, White and Brown17)

Strengths and limitations

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the latest of the very few studies to date that draw on a cross-sectional analysis of nationally representative food intake data, from both adults and non-adults, to investigate the demographic and socio-economic determinants of food preparation practices, as well as the putative associations of such practices with nutritional status, the prevalence of NCDs, and lifestyle choices.

Further longitudinal research is necessary to determine the direction of any causation between patterns of food preparation and correlates uncovered. Improving diet quality and increasing physical activity are essentially volitional, short-term behaviours, while the effects of such lifestyle changes on weight and, subsequently, health status are much less under the control of individuals and span across the course of years or even decades. This might help explain why, in the present study, a higher consumption of food prepared out of home, or at home by caregivers, correlates to poor diet quality and sedentarism, but not necessarily to a heightened risk of overweight/obesity or chronic NCDs. Historic individual data on nutritional status, any prior attempts to modify it (e.g. by dieting, increasing exercise and other means), and related outcomes are also likely to impact present-day food preparation and consumption choices and should thus be duly accounted for in future studies.(Reference Mancino, Todd and Lin68)

The use of data from the IAN–AF 2015/16, which are now 8–9 years old, may not necessarily reflect the current situation in Portugal, especially after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic may have significantly altered the dietary habits of the Portuguese population, potentially increasing at-home consumption due to lockdown and social distancing measures. Nevertheless, these are the most recent and comprehensive data from Portugal we are aware of on this topic. The MAI has not been validated in Portugal; however, this index has been indicated as good as the most utilised indexes or scores in Europe.(Reference Alberti, Fruttini and Fidanza44) Even though residual confounding remains possible, logistic regression models were adjusted for a number of relevant potential confounders. Moreover, this survey followed a harmonised methodology of dietary assessment proposed by the EFSA,(78) allowing the collection of extremely detailed food consumption-related variables — which, consequently, enabled us to explore the food and beverage preparation places, regardless of the absence of a descriptor variable that exclusively had evaluated it. The food and beverage preparation place classification applied in this study has the advantage of internal consistency, because consistently defines what is prepared at home or away from home for all participants, based on data collected about food consumption — which may be less subject to desirability bias than the data collected about cooking behaviour (such as one’s ability to complete specific a priori food preparations or cooking frequency), mostly used in other studies.(Reference Virudachalam, Long and Harhay26–Reference Wolfson, Leung and Richardson28,Reference Adams, Goffe and Adamson66,Reference Raber and Wolfson79) In addition, our system classification was informed by previously literature,(Reference Costa, Dekker and Beumer20,Reference Clifford Astbury, Penney and Adams24) and this approach, in contrast to considering only the place of consumption reported for each eating occasion, holds the potential to acknowledge the intake of foods and beverages at home that were not homemade.

Conclusions

We undertook a broad and largely generalisable exploration of the demographic and socio-economic determinants of food preparation practices in a European country where such analysis was lacking. Our findings contribute to the state of the art on the antecedents of food preparation practices and their likely impacts on diet, nutrition, and health. Specifically, they suggest that the eating patterns of certain population groups — adult men, with higher education, from multigenerational households with higher income — are prone to be composed mainly of foods and beverages prepared out of home or at home by caregivers and often linked to poor diet quality and sedentarism. Meanwhile, self-prepared food dominates the meals of more vulnerable population groups — adolescents, older adults, adults residing in rural areas, and those belonging to food-insecure households — being related to higher adherence to Mediterranean diet standards and a more active lifestyle.

However, our findings also reinforce that the pathways between food preparation practices, diet, weight, and health at the population level are highly complex and possibly less intuitive than might be expected. This calls for continued research in diverse geographies, grounded on socioecological approaches to the prevention of overweight/obesity and NCDs, as well as on more robust methodology and evidence. In particular, giving a more central role to the promotion of home cooking in future public health nutrition interventions and dietary recommendations should be undertaken with caution, as it may represent yet another burden laid on already vulnerable groups and may not translate into the expected long term health benefits to the general population.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2024.87.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participants enrolled in IAN-AF 2015/16, all members of the research team, and the institutional support from the General Directorate of Health, the Regional Health Administration Departments, the Central Administration of the Health System, and the European Food Safety Authority.

Authorship

The authors’ contributions are as follows: Mariana Rei contributed to the conception and design of the study, data analysis, and interpretation of the findings and wrote the manuscript; Daniela Correia contributed to the data analysis and writing — review and editing of the manuscript; Duarte Torres, Carla Lopes, Ana Isabel A Costa, and Sara SP Rodrigues contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the findings, and writing — review and editing of the manuscript. Ana Isabel A Costa and Sara SP Rodrigues were coordinators of the Project ‘How We Eat What We Eat – A Portrait of Meal Consumption in Portugal’. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

The IAN-AF 2015/16 received funding from the EEA Grants programme, Public Health Initiatives (grant number: PT06-000088SI3), and this study was supported by the Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos (https://www.ffms.pt/en) throughout ‘How We Eat What We Eat – A Portrait of Meal Consumption in Portugal’ Project (grant number: 1042382FCEEINV328). The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, the writing of the report, and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.