Recent developments and the baseline forecast

The UK's decision to leave the European Union (EU) is the main factor contributing to a downward revision of our baseline global growth forecast since May. In our May Review, withdrawal from the EU was discussed in an alternative set of scenarios for the UK, which showed a downside risk to our UK growth forecast. That risk has since materialised, and one of May's alternative scenarios has essentially become our new baseline.

The terms and timing of the UK's exit from the EU remain unknown, but it may well lead to substantial changes in the UK's economic and financial relations with the EU and other countries, with economic consequences abroad as well as at home. For our new baseline forecast, we have assumed, as explained in the chapter on the UK economy, that leaving the EU will take the form of the ‘Switzerland’ scenario described in the May Review (p.122). This would involve free trade in goods with the EU, but limited access to service sector markets. It would mean significantly reduced access to the UK's largest and geographically closest market, with negative implications in the medium-to-longer term for the UK's potential GDP, which would be expected to affect investment spending in the shorter term.

Figure 1. World GDP growth (from four quarters earlier)

Moreover, while the terms of exit are being considered and negotiated, unusual economic uncertainty will prevail, and this is likely to depress demand in the UK, especially investment demand, with repercussions abroad. This uncertainty may also disrupt international financial markets.

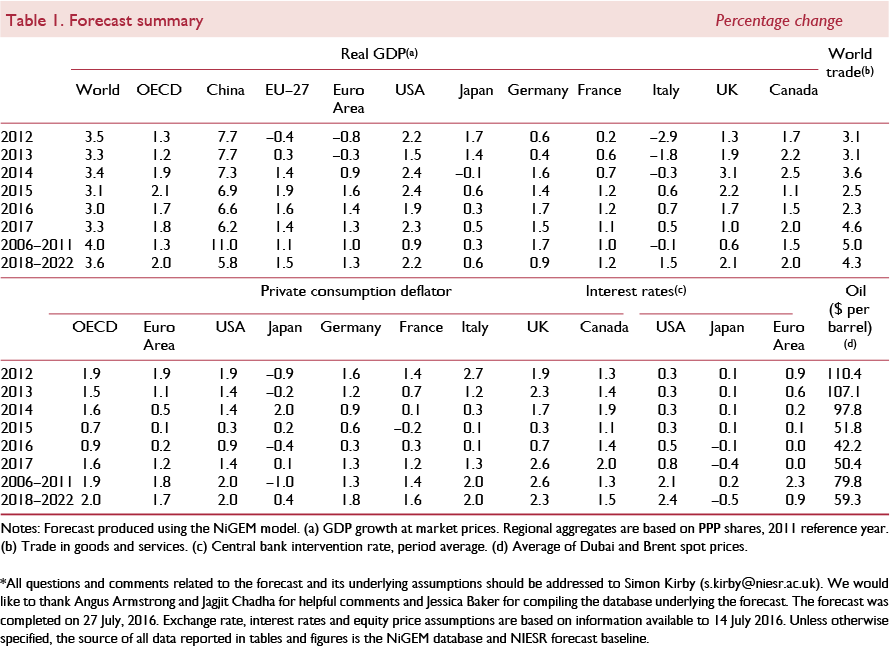

The prospect of the UK's withdrawal from the EU is a setback to a global economic outlook that was already weak and fragile. On the basis of our assumptions about the UK's exit from the EU, and taking into account other recent developments, our baseline forecast for global growth has been revised down since the May Review. Thus 2016 still seems likely to see the slowest global expansion since the 2009 recession, with world GDP growth of 3.0 per cent, while projected growth next year has been revised down to 3.3 per cent from 3.5 per cent in the May Review. The largest downward revisions to projected growth outside the UK are for the Euro Area and other countries in the EU, with the effects of the UK's decision to leave the EU, and the associated forecast revisions, importantly varying among EU countries depending partly on the closeness of their economic relations with the UK and partly on their differing vulnerabilities to the broader economic and financial consequences of the UK's exit from the EU (see Box A). For the Euro Area as a whole, projected growth has been revised down to 1.4 per cent this year and 1.3 per cent in 2017 from 1.5 and 1.7 per cent, respectively, in our May forecast.

Partly offsetting these changes are upward revisions for Brazil, Japan and Russia.

Not only because the form and timing of the UK's exit from the EU are unknown, but also because the economic responses to the related unusual economic uncertainty are difficult to predict, our forecast for the world economy, as well as for the UK economy, is itself subject to unusual uncertainty. Risks to the outlook that are related to the UK's exit from the EU are discussed below.

Data for post-referendum economic developments are virtually absent, as yet, but global growth performance was already mediocre and mixed before the UK referendum result. In the Euro Area and Japan, GDP growth in the first quarter was somewhat stronger than expected, but more recent indicators have been more subdued. In the United States, by contrast, GDP growth slowed further in the first quarter, with a decline in labour productivity, but it seems to have picked up more recently although employment growth has slowed. Among the major emerging market economies, the slowing of growth in China has continued to be moderated by official measures that seem likely to incur a cost in retarding structural change. Recessions have continued in Brazil, although market confidence has recently improved, and in Russia, where activity seems to be stabilising, helped by the partial recovery in global oil prices. India is likely to be the fastest growing major economy in 2016 for the second successive year.

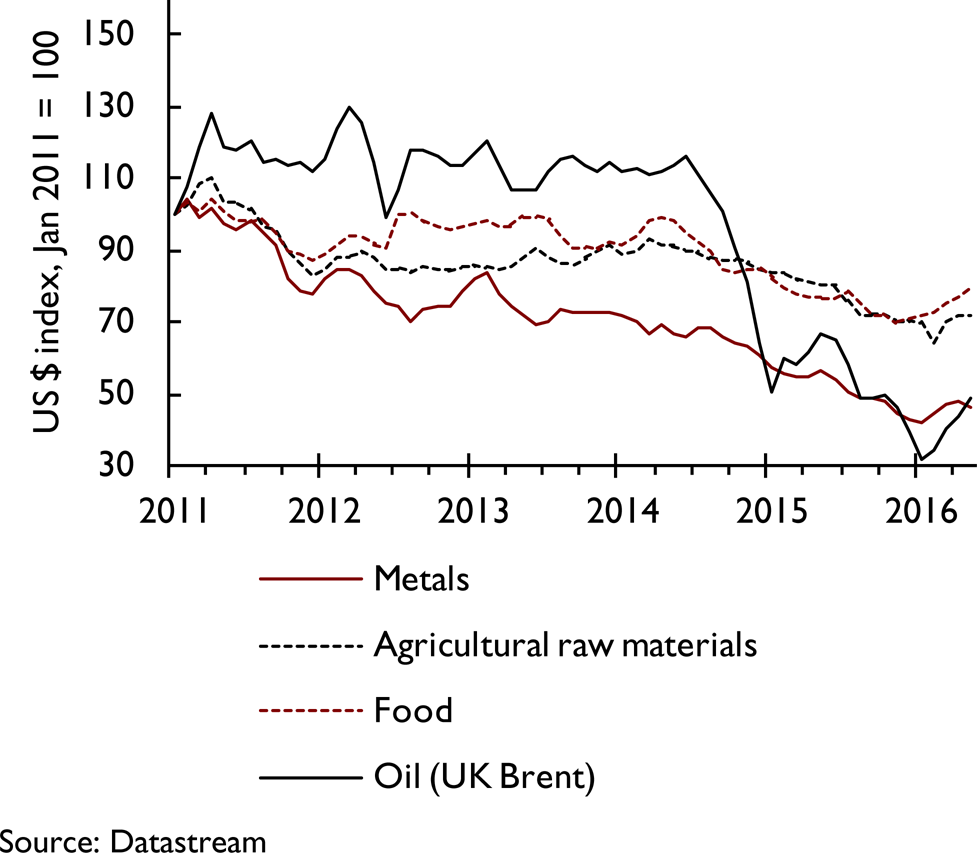

Figure 2. Commodity prices in US dollars

Inflation rates in the advanced economies have been broadly stable in recent months, with annual ‘all-items’ rates continuing to run significantly below central banks' objectives. Core inflation rates have been running closer to targets, and the upturn in global energy prices since February should help ‘all-items’ inflation rise closer to official objectives, but persistent output gaps seem likely to prevent these objectives from being met in the short term. Wage increases have remained subdued, even in economies with low unemployment, such as the United States, Japan and Germany, which adds to doubts about the reliability of any Phillips curve-type relationship. In the emerging market economies, meanwhile, inflation remains above targets in Brazil and Russia, and has risen close to the upper bound of the target range in India.

Since late April, there have been no further adjustments in the settings of monetary policy instruments in the advanced economies. In June, the ECB began implementing its programme of corporate bond purchases announced in March, and also undertook the first operations in its new series of targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTRO), intended to promote bank lending. On 21 July, President Draghi indicated that the ECB would be ready to take additional easing measures to address the consequences of the UK's decision to leave the EU after reassessing the situation on the basis of data emerging over the coming months. The US Federal Reserve in June pushed back slightly, and lowered, its expected path of rate increases. In Japan, expectations of further action to ease monetary conditions have been disappointed. Elsewhere in recent months, official interest rates have been lowered in Argentina, Australia, Korea, Malaysia and Taiwan, but raised in Colombia, Egypt and Mexico.

The result of the UK referendum surprised financial markets, which had reflected indications from opinion polls and especially betting markets that the result would be in favour of ‘Remain’. The surprise was shown most clearly in a sharp decline in UK government bond yields and a plunge in sterling on the two trading days following the result: the yield on 10-year gilts fell by 44 basis points to 1.05 per cent in this period, while sterling fell by 11 per cent against the dollar and 9 per cent in trade-weighted terms. The fall in sterling on the day after the referendum was the largest one-day drop in the period of floating exchange rates since 1972. There were also large declines in global stock markets immediately following the referendum result. However, with the major central banks having announced before the referendum result that they stood ready to provide liquidity if needed, there were no notable market disruptions. Subsequently, sterling stabilised and stock markets generally recovered.

Other developments in financial markets over the past three months have reflected the weak global outlook.

Thus, since late April, 10-year government bond yields have fallen back by 30–50 basis points in the major Euro Area economies and North America, and by about 15 basis points in Japan. None of the declines in the other advanced economies, however, has matched the fall of about 75 basis points in bond yields in the UK. In the United States, Canada and Germany, the declines in bond yields occurred mainly before the UK referendum, while in the other advanced economies, including the UK, most of the declines have occurred since it. In some cases 10-year yields have recently reached historic lows – below zero in Germany as well as Japan, where they have been negative since early March. In fact, in mid-July, Germany became the first Euro Area country to sell 10-year bonds at auction with a negative yield. (Outside the Euro Area, Switzerland was the first country to do so, in 2015.) The recent decline in long-term interest rates seems attributable partly to receding expectations of increases in official interest rates in the US following the Fed's recent deliberations, partly to revised expectations of easier monetary policy in other advanced economies (including the UK), and partly to increased risk aversion related, to some extent, to the UK referendum. It is notable, however, that there has been no widening of interest spreads in the Euro Area.

In foreign exchange markets, the main development since late April, apart from the drop in sterling – by about 9 per cent against the US dollar and 7 per cent in effective terms – has been a further appreciation of the yen against the currencies of all other major advanced economies, by about 5 per cent against the US dollar and 3 per cent in trade-weighted terms. While sterling's depreciation occurred entirely following the referendum, the yen's appreciation occurred before it. The euro's trade-weighted value is broadly unchanged since late April, although it has depreciated against the US dollar by about 3 per cent. The US dollar, meanwhile, has appreciated by about 3 per cent in effective terms. Apart from the impact of the referendum result on prospects for UK growth, monetary policy, and trade, and thus particularly on sterling, these currency movements may be attributed partly to the shifts in interest differentials described above and partly to increased risk aversion, with both the yen and the dollar apparently benefiting from haven demand. Among the major emerging market currencies, the renminbi has continued its gradual depreciation against the US dollar and in effective terms, while the Brazilian real and Russian rouble have partially recovered following earlier declines, mainly reflecting political developments in the former case and oil price developments in the latter.

Any increase that there may have been in risk aversion in recent months has not caused a general decline in equity markets. In fact, movements in stock market prices have been mixed since late April, rising in North America, the UK (in terms of the FTSE-100 and sterling), and the major emerging markets, while falling in Japan and the major economies of the Euro Area. Most of the declines in these latter cases occurred before the UK referendum, a notable exception being Spain, which is particularly exposed to the UK economy (see figures 3 and 4). The movements in equity prices in Japan and the UK, in particular, may be attributed partly to exchange rate movements. Especially in the Euro Area, the declines have been particularly severe in the financial sector, perhaps reflecting fears of the implications for bank profits of lower interest rates.

Figure 3. Claims on UK of domestic banks

Figure 4. Exports to the UK

Oil prices, in US dollar terms, have stabilised in recent months after picking up to about $45 a barrel in late April from their trough of about $26 in early February. Prices rose above $50 in early June, reflecting supply disruptions in Canada and Nigeria as well as declines in US inventories, but have fallen back to about $45 more recently, following a build-up of inventories and reports of a recovery of investment in productive capacity in the US. Other commodity prices have been broadly stable since late April: the Economist all-items index is up by about 1 per cent, despite the dollar's effective appreciation in this period, but it remains about 2 per cent lower than a year ago.

Risks to the forecast and implications for policy

We focus on risks to our baseline forecast that are related to the UK's decision to leave the EU. They are of two kinds: those concerning its prospective economic effects and those concerning the broader threat to international economic integration that it may signify. Both have important policy implications.

First, the effects of the UK's exit from the EU may turn out to be different from what we have assumed, for several reasons. The exit may take a different form from our ‘Switzerland’ scenario assumption. It may turn out to be closer to our ‘Norway’ scenario, which would involve UK membership of the EEA, with free trade in goods and services with the EU. This seems unlikely because it would seem to require the UK to agree to free movement of labour, which would presumably be unacceptable to the UK government. But if it were agreed, it would imply more favourable paths of medium-to-longer term growth of UK, EU and world GDP than in our baseline forecast, with correspondingly more favourable shorter-term implications: this possibility forms an upside risk to our baseline. But the UK's exit from the EU could alternatively be closer to our ‘WTO’ scenario, with no free trade agreements with the EU – a downside risk to our forecast. The effects of the UK's exit from the EU could also be different because we may have underestimated the effects of uncertainty, which seems more likely than that we could have overestimated them.

On balance, therefore, the risks concerning the economic effects of the UK's exit from the EU seem to be on the downside. This, together with the downward revision of our baseline, represents a setback to a global economic outlook that was already weak and vulnerable. It calls for policy action.

It seems most useful to focus on the economies of the EU, and especially the Euro Area, which are particularly exposed to the effects of the UK's exit from the EU. The economy of the Euro Area already suffers from a range of weaknesses, discussed in previous issues of this Review. It has been struggling to achieve sufficient economic growth to reduce unemployment to reasonable levels. Wide divergences in economic performance among member economies persist, with a few countries close to full employment and others with extraordinarily high unemployment levels. Moreover, there has been limited progress in reducing financial imbalances among the Area's member economies: Germany, which is close to full employment, has the largest current account surplus among the world's major economies – about 9 per cent of GDP – while the most externally indebted economies in the Area have no foreseeable prospect of achieving reasonably high employment together with external balance.

Meanwhile, public and private debt burdens remain high, aggravated by excessively low inflation as well as weak real growth. Limited fiscal space in most countries has put the burden on the ECB to support demand, but the scope for further monetary easing has become increasingly constrained. This is partly because of the possible effects of further reductions in interest rates on the profitability of a weak banking system. Meanwhile, the failure to complete the Area's banking union with a common deposit insurance scheme and a meaningful, common fiscal backstop means that dangerous links remain between risks to sovereigns and risks to national banking systems. In this regard, there has been a notable lack of progress in implementing the plan for completing the Economic and Monetary Union set out in the June 2015 Five Presidents' Report (see August 2015 Review, F17).

Against this backdrop, the UK referendum result has added to the risk of an economic slowdown in the Euro Area sharper than that shown in our baseline forecast. If the prospective path of inflation falls further below the ECB's objective, there remains scope for the central bank to increase monetary accommodation further, probably more through increased asset purchases than through further reductions in short-term interest rates. (Current constraints on asset purchases could be relieved by, for example, allowing purchases of bonds with yields below the ECB's deposit rate.) The President of the ECB has recently and appropriately emphasised the central bank's “readiness, willingness, and ability” to take additional action if warranted. But with long-term as well as short-term interest rates having now fallen to extremely low levels, in some cases below zero, monetary easing is increasingly subject to diminishing returns and heightening risks, including risks to the supply of credit as a result of pressure on banks' profitability.

Moreover, the heterogeneous prospective effects of the UK's exit from the EU across different member countries of the Euro Area imply different policy needs that cannot be met by changes in the Area's common monetary policy.

Thus the need for a more balanced policy approach has become even clearer.

First, structural reforms should be intensified. The most helpful reforms would be those that boost demand as well as supply – such as reforms that remove impediments to investment and business formation, that promote investment by raising expectations of future growth and boosting confidence, or that promote job creation by allowing firms more flexibility in hiring and firing. Reforms that lower wages and hence consumer spending are likely to be less helpful. In fact, in Germany, in particular, policies to boost wage growth would promote a reduction of external imbalances in the Area and globally. Stronger action to reduce banking sector risks, including promoting the resolution of non-performing loans, is also important. This may require a pragmatic application of the EU's Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive. Also with regard to the financial sector, a mercantilist approach by Euro Area countries to gaining financial services at the expense of the City of London could backfire by raising the financing costs of banks within the Area.

Second, there is underutilised scope for fiscal policy to support demand. After several years of consolidation, fiscal policy in the Area this year is expected to be mildly expansionary, largely reflecting refugee-related spending in Germany. But little further fiscal stimulus is in prospect. Taking into account debt sustainability considerations as well as targets under the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and national fiscal rules, fiscal space seems limited, and concentrated in countries such as Germany with small or no output gaps and little need for demand support (figure 5). However, recent further declines in borrowing costs to extraordinarily low levels have increased both fiscal space and the prospective profitability of investment projects.

These considerations suggest that fiscal policy could play a larger role in managing and supporting demand in several ways, and thus relieve the burden on monetary policy. First, countries like Germany that have fiscal space should use it to promote investment, which would boost productive potential as well as current demand and activity. Second, all countries can make their fiscal policies more conducive to growth by, for example, replacing unproductive spending by productive investment, and reducing marginal tax rates while broadening tax bases. Third, if the risk of a severe downturn in the Euro Area materialises, fiscal adjustment required under the SGP should be suspended, using the escape clause under the Pact. Fourth, mechanisms for fiscal support at Euro Area level need to be developed, as envisaged in the Five Presidents' Report's call for a fiscal union, with a macroeconomic stablilisation function to improve the cushioning of economic shocks.

In addition, it should be recognised that the prospective heterogeneous effects of the UK's decision to leave the EU across the Area's member countries are likely to call for differentiated demand management, which only fiscal policy can provide.

The second kind of risks is that the referendum result may presage a broader retreat from globalisation – meaning the increasing international economic integration of countries through more open trade, financial flows, and labour mobility, which has been a major feature of the postwar period. The vote may be viewed as one of a number of indications of a strengthening sentiment across several advanced economies opposed to such integration.

Progress in increasing international economic openness has already slowed in recent years. The latest WTO (World Trade Organization) round of global trade negotiations, the Doha Round that began in 2001, is virtually dead, with attention having shifted to the negotiation of various regional and bilateral arrangements. According to WTO statistics, world trade growth has slowed significantly since 2008, from an average of over 7 per cent between 1990 and 2008 to less than 3 per cent between 2009 and 2015; 2015 marked the fourth consecutive year with global trade growth below 3 per cent. And protectionist actions seem to have intensified recently: the WTO reported in June that protectionist measures had been introduced by G20 economies in the previous seven months at the highest monthly rate since the WTO began monitoring the G20 in 2009. Moreover, since the global financial crisis, cross-border finance has become more fragmented, with less cross-border exposure as banks, in particular, have consolidated and been pressured to serve domestic needs.

The UK referendum result has been widely interpreted as one example – perhaps the clearest thus far – of evidence of a more widespread disillusionment with, and opposition to, international economic integration. This has also been apparent in other countries – in some cases in the election of governments with more inward-looking policies, and in others in increased electoral support for fringe parties and political leaders opposed to the liberalisation of international trade, finance, and migration.

The grounds for continuing to believe that open international economic relations are beneficial to a country's economic welfare remain solid; and conversely, a retreat to more defensive, inward-looking economic policies would threaten further damage to economic growth, employment, and welfare worldwide.

On the other hand, however, there is no doubt that there have been losers as well as winners from globalisation. Indeed, it is not possible to have the gains from increased economic openness without making some worse off, at least in the short run. It is also clear that unfettered international labour mobility can disturb social cohesion, particularly when immigration is highly concentrated geographically. Losers from globalisation have often included workers whose products have had to compete with imported products produced abroad with cheaper labour, and workers who have had to compete with immigrant labour from lower-income countries. (Winners, of course, have included the consumers of the cheaper imported and immigrant-produced products.) If the support for international economic integration is to be maintained so that the risk of damaging protectionist policies is to be averted, more active policies appear to be needed to compensate and support globalisation's losers, including through income support, retraining, and other active labour market policies, and through action to promote alternative employment opportunities. This may well require higher taxes on globalisation's winners.

The US Trade Adjustment Assistance Program, which for more than 50 years has provided support for workers who have lost their jobs as a result of foreign trade, through the provision of job training, job search and relocation allowances, and income support, represents one kind of approach, which may need to be used on a much larger scale.

There may also have to be recognition that the requirements of social cohesion call for more restrictive migration policies than would serve to maximise the growth of GDP.

Indeed, those countries that have recently pursued fiscal consolidation in pursuit of arguably arbitrary budget targets may, by cutting welfare spending, have exacerbated the losers' problems.

Box A. The UK's decision to leave the EU: the impact on European economies

This box updates the analysis in Reference Lloyd and MeaningLloyd et al. (2016) which used movements in financial market data from the immediate aftermath of the UK referendum to analyse the possible impacts on European economies. We calibrate shocks to a variety of risk premia in the UK and EU based on calibrations from financial market data and other indicators from the post referendum period and feed these into our global econometric model, NiGEM, to assess the overall impacts. This analysis encompasses only short-run dynamics; it does not include any impacts from a transition by the UK to an alternative relationship with the EU.Footnote 1

The referendum result was immediately followed by movements in financial and currency markets as participants evaluated the possible impacts on the UK and spillovers to the EU economy. As predicted by Reference Baker, Carreras, Ebell, Hurst, Kirby, Meaning, Piggott and WarrenBaker et al. (2016), the impact on sterling was a sharp depreciation, which continued for several days. Against the US dollar, the depreciation has since stabilised at around 9 per cent. The euro has depreciated against the dollar, by about 2.5 per cent since the referendum.

Equity price indices also fell sharply in the UK and across other major European stock markets in the days following the referendum but have since then recovered some of the lost ground.Footnote 2Reference Baker, Carreras, Ebell, Hurst, Kirby, Meaning, Piggott and WarrenBaker et al. (2016) assumed that there would be an increase in risk premia on sovereign bonds, but since the referendum sovereign yields have fallen. While some of this represents a shift in interest rate expectations towards a looser monetary policy path, there has also been a fall in risk premia as investors demand for safer assets increased (see Reference Lloyd and MeaningLloyd and Meaning, 2016).

In NiGEM, the cost of funding for firms is measured as the spread between interest rates on corporate and government bonds. The yield on corporate bonds has remained broadly stable since the referendum; this implies that there has been an increase in the risk premia broadly equal to the decrease on government yields.

We further apply an uncertainty shock to the UK alone, which feeds directly into business investment as described in Reference Baker, Carreras, Ebell, Hurst, Kirby, Meaning, Piggott and WarrenBaker et al. (2016). Measures of uncertainty in the UK economy leading up to and after the referendum have been at elevated levels; Box B in the UK chapter of this Review provides a fuller account. We calibrate shocks to reflect the movement in the data above and input these into NiGEM. The impacts on the UK and the EU are plotted in figure A1. The impact on the rest of the EU is a direct spillover from lower UK GDP growth and higher levels of sovereign risk premia in countries such as Greece and Portugal. In aggregate the effect on Europe is that GDP is 0.4 per cent below the ‘Remain’ counterfactual in 2017. However, the negative impact is not symmetric across countries. There are significantly smaller impacts on France and Germany than on Ireland, Spain and Italy. For Ireland, this is unsurprising given the relative importance of the UK economy as an export destination. For the other economies the importance of UK trade is much smaller. In these cases the implied movements in premia may reflect vulnerabilities to the broader economic and financial consequences of the decision to leave the EU: for example the implications of lower interest rates on the already troubled Italian banking sector. This also highlights the presence of significant downside risks to the UK's exit from the EU, particularly if financial linkages start to amplify the economic shocks.

Figure A1. Impact of UK withdrawal on EU GDP levels

Notes

1 Reference Ebell and WarrenEbell and Warren (2016) assess the possible impacts of alternative trade on the UK economy.

2 We use the FTSE 250 to calibrate this shock.

This box was prepared by James Warren.