Communities across America are grappling with the presence of public monuments to the Confederacy. Responsibility for deciding whether to keep or remove these monuments has fallen largely on city councils, county commissioners, and school boards, with the occasional exception of unilateral action by a mayor or a governor. This racially charged issue is one on which Americans are closely divided (Quinnipiac University 2017). Decisions to remove or not remove monuments have sparked unrest and violence, including the widely covered “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. What if instead of allowing elected officials to make these decisions, voters had the final say? Would this have an effect on how the public feels about the outcome, win or lose?

Whether citizens should be allowed to directly participate in decisions of governance has been a subject of debate since direct legislation was incorporated into state and local politics in the Progressive Era (Smith and Tolbert Reference Smith and Tolbert2004). There are ongoing concerns about citizen competence. Yet, equality in political rights is a basic tenet of democracy. Schwartzberg’s (Reference Schwartzberg2013) work explained one reason why: equal voice in decision making conveys and instantiates respect for each citizen’s judgment. If all participate in making a decision, then that decision may be seen as fairer and more legitimate than a decision-making process limited to the few.

We used a survey experiment to examine how incorporation of direct participation affects public attitudes about the decision to remove a Confederate monument. We found that respondents reacted significantly more positively to the outcome when voters, as opposed to an elected city council, made the decision. These findings hold (and additional significant differences present themselves) even when we focused solely on respondents whose preferred outcome on the question of Confederate statues was not achieved. Our findings build on previous work on general attitudes toward direct democracy as well as on the influence of direct participation on citizen opinions. Our results speak to the potential of direct democracy to enhance positive reactions about decisions, particularly when the public is divided and a decision is highly controversial.

We used a survey experiment to examine how incorporation of direct participation affects public attitudes about the decision to remove a Confederate monument.

DIRECT DEMOCRACY AND CITIZEN ATTITUDES

With the proliferation of ballot initiatives and referenda across the United States in recent decades, voters have weighed in on a host of complex issues, including constitutional amendments, territorial changes, national to local control, taxation, and the general role of government (Budge Reference Budge, Rhodes, Binder and Rockman2006). Although the effect of citizens’ direct participation on quality of governance is debated, a growing literature suggests that it is positive. People who live in states with ballot initiatives and referenda appear to be more knowledgeable due to increased issue coverage in the media, increased campaign activity, and more opportunities for engagement (Tolbert, McNeal, and Smith Reference Tolbert, McNeal and Smith2003; Tolbert and Smith Reference Tolbert and Smith2005). States that allow for ballot initiatives and referenda tend to have an increase in multiple types of participation (Damore and Nicholson Reference Damore and Nicholson2014; Dyck and Seabrook Reference Dyck and Seabrook2010; Tolbert, McNeal, and Smith Reference Tolbert, McNeal and Smith2003). Direct legislation appears to increase a sense of government responsiveness in people (Bowler and Donovan Reference Bowler and Donovan2002), whereas electoral participation increases perceptions of democratic processes (Kostelka and Blais Reference Kostelka and Blais2018).

There also is evidence that citizens have positive views toward direct democracy. In states that have direct legislation (e.g., California and Oregon), public opinion is highly favorable toward the institution (Bowler and Donovan Reference Bowler and Donovan2002). Even voters in states that do not allow for direct participation (e.g., Alabama) are favorable toward the institution and claim they would like it in their state (Waters Reference Waters2002). Americans across the political spectrum perceive decision making as clearly being in the hands of elected officials, but they would prefer more balance between direct democracy and institutional or representative democracy (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002).

However, one concern with this research on the behavioral effects of direct democracy is that much of it is based on correlations between the number of initiatives and referenda on one hand and citizen attitudes and behaviors on the other (Biggers Reference Biggers2014). These studies do not always address concerns with endogeneity or, more important, how effects of direct democracy might vary from issue to issue, and campaign to campaign (Biggers Reference Biggers2014). When these concerns are considered, moral-issue propositions appear most likely to increase voter turnout (Biggers Reference Biggers2014). This raises a question: Will citizens feel differently toward a morally controversial issue made by the processes of direct democracy rather than by elected officials?

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

To determine if the form of decision making affects attitudes toward a decision, we conducted a survey experiment. The experiment was designed in Qualtrics and was offered as a task to interested parties via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, a well-known, often-used, and well-regarded source for recruiting survey respondents.Footnote 1 Potential respondents were informed in the recruitment materials that the survey focused on Confederate statues. In March 2018, 401 individuals took part in the experiment.

After consenting to participate, respondents answered a pretest questionnaire focusing on demographics and attitudes toward politics.Footnote 2 Respondents then were told they would read a story about a city that faced the question of keeping or removing a Confederate monument in a city park.Footnote 3 In this story, the city of Owingsville, Kentucky, is deciding whether a statue of Confederate General John Bell Hood (a native of Owingsville) should be removed or kept on a pedestal in a city park. Respondents were given biographical information about Hood: he was a graduate of the US Military Academy, he served in the 2nd US Cavalry in Texas, he joined the Confederate Army in 1861, he was wounded at Gettysburg and Chickamauga, and he was promoted to General in 1864. They also were given details about the statue (i.e., it has been in the park since 1905) and were told that the decision regarding the statue followed weeks of debate among local groups (many members of which had assembled near the statue, waiting on the verdict). The story was entirely simulated in nature; although Confederate General John Bell Hood was born in Owingsville, Kentucky, there is no statue of him there. The story was intended to mirror—and, in fact, borrowed details from—real controversies taking place in cities across the United States.Footnote 4

The stories read by respondents were exactly the same in every way except for two details: the decision of whether to keep or remove the statue and the body that made that decision. Half of the respondents read a story in which Owingsville would keep the statue; the other half read a story in which it would remove the statue. Half of the respondents read a story in which the Owingsville City Council made the decision regarding the statue (i.e., a representative-democracy–based outcome); the other half read a story in which the voters of Owingsville made the decision (i.e., a direct-democracy–based outcome). In treatments in which voters made the decision, it was always a 70%–30% outcome; for the sake of symmetry, in treatments in which the City Council made the decision, the Council vote was always 7–3.Footnote 5 The result of these manipulations was a 2x2 design with four treatment groups (each of which had approximately 100 respondents): Council-Keep, Council-Remove, Voters-Keep, and Voters-Remove.Footnote 6

After reading their story, respondents proceeded to a questionnaire on various facets of the story and the issue.Footnote 7 They were asked if the decision was fair, was legitimate, whether the voices of citizens had been heard, and whether both sides of the debate had their voices heard. Respondents also were asked if the decision increased their confidence in our system of government and whether they believed the decision would settle the debate about Confederate statues in Owingsville once and for all. The survey closed with questions on race and Confederate symbols, including whether respondents personally supported or opposed removing Confederate statues.

FINDINGS

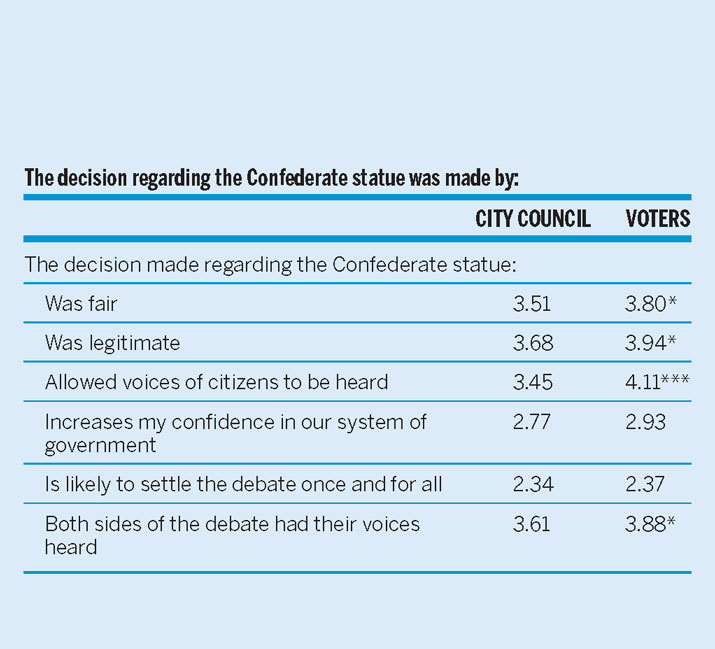

We examined the effects of direct and representative democracy on attitudes toward the decision-making process by comparing individuals who read that the City Council made the decision regarding the Confederate statue to those who read that the voters made the decision. We analyzed differences in means to understand the dynamics within and between these two groups (table 1).Footnote 8

Table 1 reveals that, across several metrics, respondents who read that the decision concerning the Confederate statue was made by voters reacted significantly more positively to the process than those who read that the decision was made by the City Council.

Table 1 Direct Versus Representative Democracy and Effects on Respondent Reactions

Notes: N=401. Scale ranges from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Table 1 reveals that, across several metrics, respondents who read that the decision concerning the Confederate statue was made by voters reacted significantly more positively to the process than those who read that the decision was made by the City Council. Respondents who read that voters made the decision were significantly more likely to agree that the decision was fair and legitimate. They also were significantly more likely to agree that not only were the voices of citizens heard but also that both sides of the debate had their voices heard. However, the distinction between exposure to direct democracy and exposure to representative democracy was not significant across the board. There were no significant differences in considering how the decision might increase confidence in our system of government. Additionally, one group was no more likely than the other to agree that the debate about statues was likely to be settled once and for all. In fact, both groups’ means were closest to “disagree” on that question.

But what about personal opinions on Confederate monuments of those individuals in our survey? Might they condition reactions to information learned in the treatments? How might an individual who believes that statues should be removed react to a treatment in which a statue is kept in place? How might an individual who thinks a city should keep its monuments respond to a treatment in which a monument is taken down? Moreover, how might these types of respondents feel differently if the decision was made via direct democracy versus representative democracy? Table 2 explores the reactions of those whose personal views were diametrically opposed to the decision made in the treatment they read. These individuals are referred to as “oppositionals.”

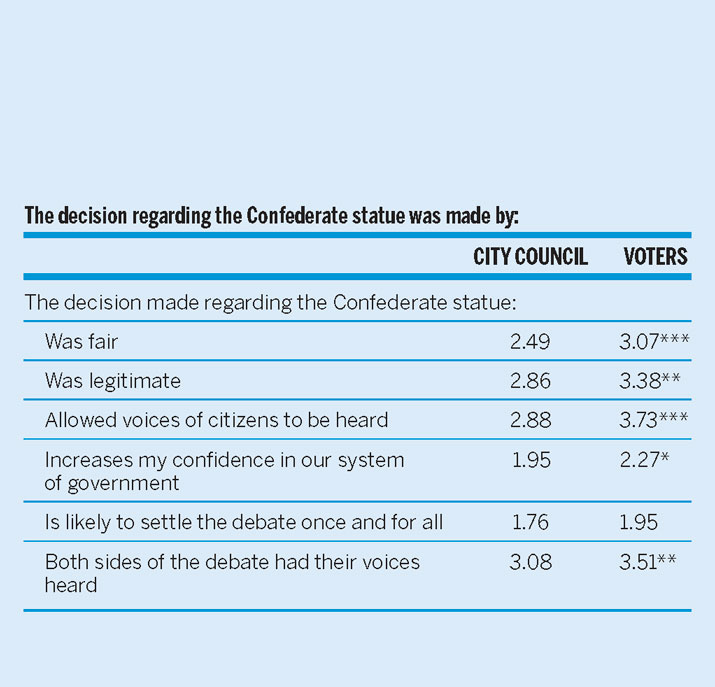

Table 2 Direct Versus Representative Democracy and Effects on Reactions of “Oppositional” Respondents

Notes: N=159. Scale ranges from 1(Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Two types of respondents included in the analyses in table 1 were removed from the analyses in table 2: (1) those who received a treatment in which the decision matched their personal beliefs about what should be done with statues, and (2) those who stated that they were unsure if statues should be removed from public spaces.Footnote 9 This resulted in 159 oppositionals who were either pro-removal but read about a statue being kept or were for keeping a statue but read about it being removed. We proceeded similarly as in table 1, comparing reactions of oppositionals whose personal views lost because of a decision made via representative democracy (i.e., the City Council) to those whose personal views lost because of a decision made via direct democracy (i.e., the voters).

The mean responses of oppositionals, across the board, were less positive when compared to those of the entire pool of respondents (see table 1). As in table 1, however, we found significantly higher levels of positivity among oppositional respondents who read that voters had the final say concerning Confederate statues when compared to oppositionals who read that the City Council made the decision. Oppositionals who read that voters made the decision regarding the statue were significantly more likely to state that the decision was fair, was legitimate, and allowed the voices of citizens to be heard than those who read that the City Council made the decision. It is interesting that the difference between these groups straddles the exact middle of our 5-point scale. Those oppositionals who read that voters made the decision had an average response between 3 and 4 (i.e., “neither agree nor disagree” and “agree”) on the questions of fairness, legitimacy, and citizen voices being heard. Oppositionals who read that the City Council made the decision had average responses between 2 and 3 (i.e., “disagree” and “neither agree nor disagree”) on these questions. Both groups had an average response between 3 and 4 on the question of whether both sides of the debate had their voices heard; however, the group of oppositionals who read that voters made the decision were significantly likely to deliver an even more positive response.

Not all of the reactions among oppositionals who read that voters made the decision on statues were positive; nevertheless, many remained significantly higher than those in the oppositional group exposed to decision making via representative democracy. Oppositionals who read about direct democracy being applied to the question of Confederate statues delivered an average response of 2.27 about whether the decision increased their confidence in our system of government. This average is much closer to “disagree” than most of those discussed so far, but it is still significantly higher than the average of 1.95 delivered by the oppositional group that read about the City Council making the decision. This significant difference on the question of confidence in government also created a distinction between our findings in tables 1 and 2. The distinction does not extend to the question of whether the decision regarding the Confederate statue would settle the debate once and for all. Unsurprisingly, oppositionals were even more pessimistic on this question than the overall set of individuals surveyed. Both the direct-democracy and the representative-democracy subgroups clearly and similarly disagreed with the notion that a decision about the statue meant that the question regarding monuments to the Confederacy is moot.

CONCLUSION

Our findings revealed distinctly higher levels of satisfaction with outcomes among those who learned that a decision had been made by voters as opposed to those who heard that a decision had been made by the City Council. These findings held across many potential definitions of satisfaction: fairness, legitimacy, and the beliefs that the voices of citizens were heard and that both sides of the debate were heard. The findings also held when focusing on oppositionals, who disagreed with the outcome about which they read. Our findings support the conclusion that direct participation in decision making can enhance satisfaction with a decision.

These results may have a prescriptive function for cities facing dilemmas about Confederate statues in the future (and other highly controversial decisions more generally). Survey research revealed that this policy question is fraught with conflict, with a public closely divided on whether statues should remain or should go. Voters may not necessarily like the outcome if it is made by their fellow citizens, but they appear to react more positively overall to the process than if it is made by an elected body. The potential for post-decision conflict might be minimized as a result. From a democratic perspective, this finding is not surprising. Allowing all citizens to participate equally in the decision-making process signals respect and inclusion.

The experimental context also points to the types of issues in which direct legislation might be particularly valuable: divisive issues as well as those that require little technical knowledge and in which moral dimensions dominate. Moral-issue propositions tend to draw in peripheral voters (Biggers Reference Biggers2014). In addition, a long-standing concern with direct legislation is voter competence. Citizens often appear woefully uninformed, susceptible to the influence of business interests, unqualified to decipher ballots that are frequently complex, and unable to lean on the cues provided by elections (e.g., partisanship or a candidate’s history) (Magleby Reference Magleby1984; Reference Magleby1994). Whereas there is reasonable debate about whether citizens have the capacity to decide complex technical questions, many issues (e.g., Confederate monuments), are not technically complex but rather morally complex. Our results prompt further questions. Are respondents more satisfied when decisions are made by voters in any policy context, and might this be conditioned by the extent to which said policy area is laden with conflict or morality? How might framing of the issue—for example, making an explicit racial appeal (Hutchings, Walton, and Benjamin Reference Hutchings, Walton and Benjamin2010)—affect the outcome? These questions are for future research to explore.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000611