The scene is West Berlin, 1979. Christiane F.'s memoir Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo Footnote 1 has just come out, shocking readers with its account of a drug-fuelled youth subculture around the main West Berlin train station. The city's young people are not subject to mandatory national service and there's no official closing time in bars. The Staatsbibliothek am Potsdamer Platz, the western counterpart to the Berlin State Library on Unter den Linden in East Berlin, has just opened, and other cultural landmarks on the west side, such as the Neue Nationalgalerie, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and the Berliner Philharmonie concert hall, designed by Hans Scharoun, have been open for a decade or more. David Bowie has just moved on, after living in relative anonymity at Hauptstrasse 155 from 1976 to 1978 and recording at Hansa Studios. Air Berlin begins operation this year as an American charter enterprise to provide service to the city, since the German Democratic Republic (usually referred to in the west as East Germany) has blocked West German commercial airliners from using the air routes. The Berlin Wall looms large, both literally and figuratively, as a foreboding perimeter around West Berlin's 185 square miles. And Joan La Barbara arrives in early January, which she remembers as ‘snowy, grey, cold’.Footnote 2

Many have attempted to imagine or recreate the soundscape of Cold War-era Berlin,Footnote 3 as La Barbara herself did in the sound painting Berliner Träume (1983):

I visited Berlin for the first time in 1972, returning again and again and eventually living there as a Composer-in-Residence for the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst Künstler-programm. My relationship to the city became a profound one for me and is reflected in this work. The 16 tracks of vocal sound include circular singing (singing on the inhale as well as the exhale) and rhythmic breathing inspired by the Inuit Throat Singers, multiphonics, words and phrases in German and modular ascending linear phrases. In addition, three specific synthesized sounds (the only ones on this CD) were used: the low, sub-bass rumble/chug of a locomotive approaching and departing from West to East and from East to West (my first apartment in Berlin was near the main train depot, the Zoo station), the strident hi-lo police siren (somehow disconcerting to American ears), and a sonic boom (the Russian or East German planes reminding Berliners of their fragile and tenuous existence in the walled island), all sounds to which one adjusts and which remain as part of my memory of my years there, even though, happily, the circumstances and tensions have changed radically since the tearing down of The Wall. If this work is at once somber, carefree, joyous, melancholy and thoughtful, it effectively reflects my personal remembrance of Berlin.Footnote 4

During a 1984 interview with Charles Amirkhanian an audience member said to her that the effect of the piece was claustrophobic, particularly the breathing. She replied, ‘I mean, there is something a little bit claustrophobic about the city of Berlin.’Footnote 5

Turning from the sonification of her memories of West Berlin, this article proposes adding La Barbara's music-making in West Berlin, specifically in 1979, to the project of imagining the sound of that time and place. She spent much of the year there under the auspices of the prestigious DAAD Berliner Künstlerprogramm (the Berlin Artists’ Programme of the German Academic Exchange Service). This chronicle expands the otherwise male-dominated accounts of sound in that time and place, touching upon the materiality (her voice, magnetic tape), technologies (equipment), conditions (spaces), networks (collaborators) and sites of La Barbara's work. Her music-making was often created with, committed to and transmitted on magnetic tape, a medium whose distinctive qualities and affordances are well documented by Andrea F. Bohlman, Peter McMurray and others in a recent special issue of Twentieth-Century Music.Footnote 6 She recorded two commissioned works at the studios of RIAS (Radio in the American Sector) that year, ShadowSong and Klee Alee, and then released them on her album Reluctant Gypsy in 1980, projecting well beyond the confines of the RIAS commission and broadcast.Footnote 7 The late 1970s and early 1980s also represent a distinctive moment in the history of recording, as the gradual transition from analogue to digital systems often required equipment designed to bridge that gap in the studio.Footnote 8 Her work in European studios more broadly (Radio Bremen, WDR, Radio France, VPRO in Holland) is a fertile topic for further research that would be a valuable contribution to the burgeoning literature on electronic-music studios as sites of cultural work during the Cold War and beyond.Footnote 9

I will also consider the role of the Künstlerprogramm in facilitating La Barbara's music-making and, by extension, her contribution to the Cold War soundscape. As a guest of the Künstlerprogramm, La Barbara enjoyed tremendous artistic freedom to design her own projects. She recalled, ‘I had no responsibilities other than to do my work. That particular grant is all about just going and being an artist, and living there, and participating in the cultural life of the city.’Footnote 10 She drew on programme support as needed (logistics, equipment rentals, networking, etc.). For example, La Barbara's file in the Künstlerprogramm archive reveals that Helga Retzer, then director of the programme, rented a Sony amplifier for a concert, facilitated arrangements with venues elsewhere, such as the Baack'scher Kunstraum in Cologne, and acted as correspondence intermediary when La Barbara was out of the city.Footnote 11 (It also attests to the ongoing relationship between La Barbara and the Künstlerprogramm, with correspondence dating well into the 2000s.)

She used West Berlin as a base of operations for travel in Europe and back to the US. The Künstlerprogramm encouraged and supported work outside the city, as evidenced by the rigorous travel itinerary on file: she travelled from West Berlin for a tour in the US (5 February–21 March) as well as for performances in Cologne (May), Munich (June), Vienna (September), Paris, Brussels and Kassel (October). These events were often multimedia in nature, with visual artists contributing work as well. She and husband Morton Subotnick also made an unofficial visit that December to Zeuthen, south of the city in East Germany, to meet with composer Paul-Heinz Dittrich.Footnote 12 Within the city, the Künstlerprogramm facilitated the performance of her music at numerous locations: a former factory turned artists’ workshop, the daadgalerie, the Hotel Steiner, the Hochschule der Künste, a radio recording studio. This conjured for me an image of spatialisation through her peregrinations, as if the Künstlerprogramm were a sound designer for the quintessential Cold War urban space.

The Künstlerprogramm was created specifically for this Cold War environment.Footnote 13 West Berlin was a geopolitical anomaly, the result of the occupation and division of the city by the American, British, French and Soviet allies after the Second World War. By 1979 most westerners referred to West Berlin (the former American, British and French zones) simply as ‘Berlin’, as if the eastern side (the former Soviet zone) did not exist; the government of the Federal Republic of Germany in Bonn (West Germany) identified it as ‘Berlin (West)’ or ‘West-Berlin’; the East German state called it ‘Westberlin’, some maps simply rendering it as a blank space between the East side of the city and Potsdam on the western side).Footnote 14 Initiated by the Ford Foundation in 1962, just one year after East Germany built the Berlin Wall, the Künstlerprogramm was designed to inject cultural energy into a city that was cut off from the rest of the world. After 1966 it was administered solely by the DAAD from offices in Bonn and Berlin. Each year it invited about 20 artists to participate and thus it became a conduit for both established and emerging artists to the western half of the city. The list of American musicians who preceded La Barbara through its portal reads like a Who's Who of experimental music: Frederic Rzewski (1963), Elliott Carter (1964), Earle Brown (1970), Morton Feldman (1971), John Cage (1972), Christian Wolff (1974), Steve Reich (1974) and Terry Riley (1978), all of whom were embedded in the Künstlerprogramm's networks of festivals, venues and artists, both formal and informal, spread across West Berlin, West Germany, western Europe and Austria (politically neutral at the time).Footnote 15 The Künstlerprogramm was, and remains, a golden opportunity for artists to cultivate international careers. During the Cold War it was also an instrument of cultural diplomacy, as it ‘served the United States’ cultural objective – similar to the goals of reeducation – of counteracting West Berlin's isolation from artistic developments in the rest of the world’.Footnote 16 Andreas Daum has written about the unique role Berlin played in the American imaginary as both front and frontier during the Cold War, and while he does not include the Künstlerprogramm in his analysis, it could fit into that reading.Footnote 17

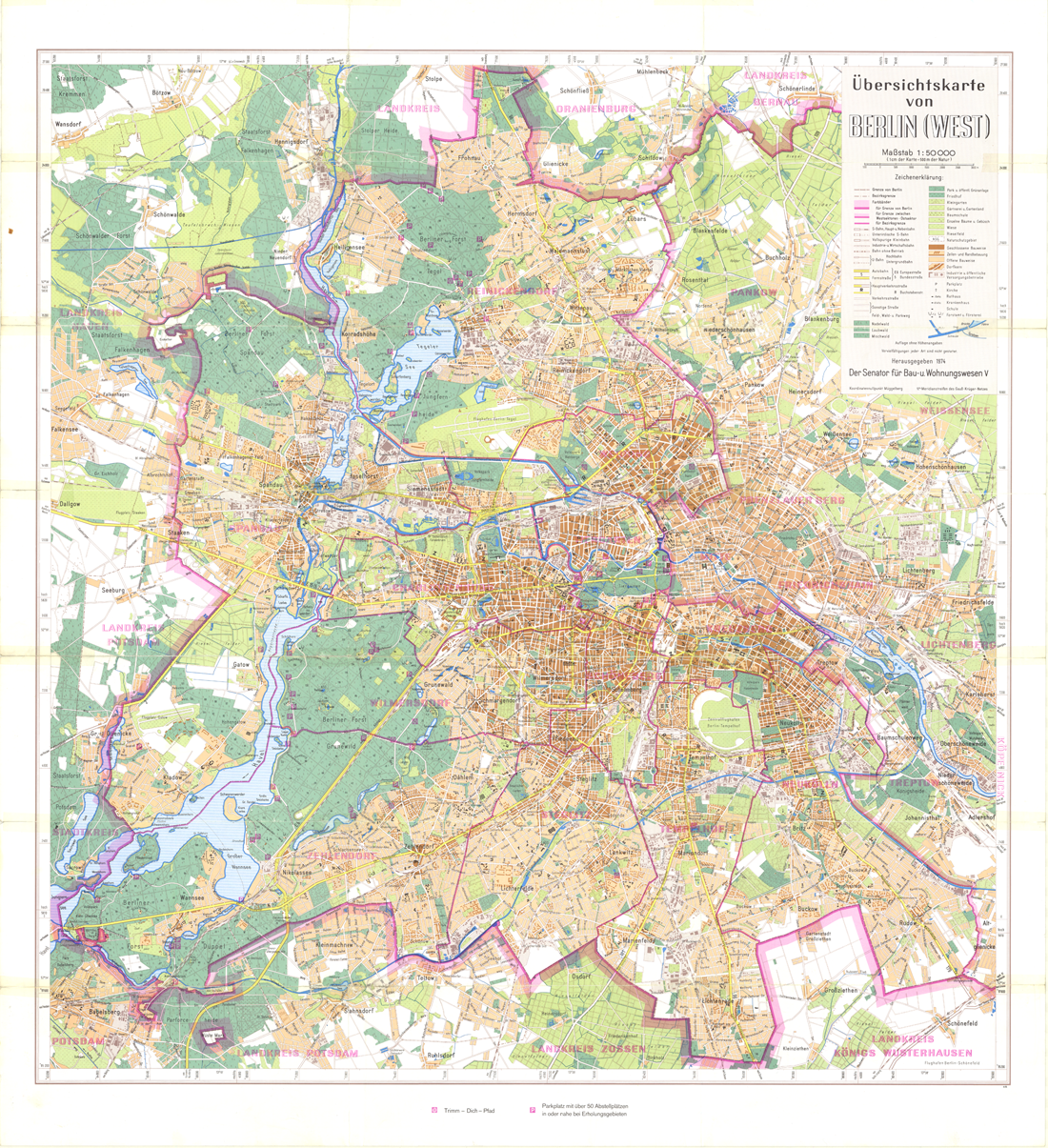

The remainder of this article maps the locations in West Berlin that were significant for La Barbara in 1979 and describes the music-making she undertook there where relevant. Figure 1 is an overview map of West Berlin for scale and orientation; the Wall is marked in a thick red-pink line around the perimeter. Figure 2 is a close-up of the districts in which La Barbara was active (Charlottenburg, Wilmersdorf, Schöneberg); these are demarcated with thinner, darker red lines. Each address is numbered below and plotted on the map in Figure 2. Numbers 1–11 show the spaces in which she moved; the descriptions give a sense of each space and her experience in it. Numbers 12–19 represent other venues at which the Künstlerprogramm hosted events that year.

Figure 1: Map of West Berlin, 1974. Used with permission of Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung, Bauen und Wohnen Abteilung III, Geoinformation-Referat III C, Topographische Karten, Fehrbelliner Platz 1, 10707 Berlin. Data license www.govdata.de/dl-de/by-2-0.

Figure 2: Map of La Barbara's locations in West Berlin, 1979. A close-up of the map in Figure 1, modified and edited on 3 March 2022 by Connor Gilmore, Vanderbilt University.

Kantstrasse 154A

La Barbara arrived in January and moved into a flat at Kantstrasse 154A, on the corner of Fasanenstrasse, above the Paris Bar. It was very conveniently located, just a couple of blocks southwest of the primary transportation hub for West Berlin (Berlin Zoologischer Garten train station) and near several venues she would frequent that year. At least two previous Künstlerprogramm recipients, Stefan von Heune and Michelangelo Pistoletto, had lived in the same apartment. The extraordinary new-music flautist Eberhard Blum lived around the corner on Fasanenstrasse with his wife, artist Ann Holyoke Lehmann; La Barbara collaborated with Blum on the Text-Sound festival later that year. Upon arrival she arranged to rent a Bechstein piano for the year.Footnote 18 She began composing Responsive Resonance (with feathers) for piano and tape, commissioned by Joan Tower, on that instrument on 7 January, ‘doing a lot inside the piano with objects I found in the apartment (a small wooden ball, paper clips, wooden sticks bouncing off the strings like dulcimer hammers, chopsticks, shells)’.Footnote 19

Zwiebelfisch, Savignyplatz 7

‘A Kneipe [local neighbourhood bar] that many artists hung out at and was open into the wee hours of the morning. It was always very welcoming. There were chess boards on tables and if one got hungry, they would serve “available food”. I recall a cauliflower dish with cheese.’Footnote 20

Alt-Lietzow 28

The Standesamt (Registry Office) Charlottenburg, where she and Morton Subotnick were married on 18 December 1979. Blum acted as witness, and Barbara Richter from the DAAD served as translator. Blum had already accompanied them to the office several times to clarify their rather complicated situation (‘I had been married once before and Mort had been married twice before and Mort's name on his birth certificate is Morris, so lots of 'splainin’ to do’).Footnote 21

Klausenerplatz 19

The site of a former factory repurposed as an artist's workshop and reopened under the moniker K19 in 1978. La Barbara and Blum co-produced the Text-Sound Festival there (the Künstlerprogramm documented it as ‘Sprechtexte, Lautgedichte, Klangwerkstücke’), featuring performances of pieces by the Italian Futurists as well as La Barbara, Emmett Williams, Steve Reich, Jackson Mac Low, John Cage, Kurt Schwitters, Ernst Jandl and others. The artist Peter Sedgley created the ‘visual ambience’, and the festival sold out each night.Footnote 22 La Barbara premiered her California Chant (‘Raicha Tria’) for amplified or unamplified voice there on 27 October. Other performers included Jolyon Brettingham-Smith and Toni Stooss. Figure 3 shows La Barbara performing at K19 in the Text-Sound festival.

Figure 3: Joan La Barbara performing at the Text-Sound Festival at K19 in October 1979, photograph by Ingeborg (Lommatzsch) Sedgley, used with permission of the photographer, taken in the context of La Barbara's residency at the DAAD Berliner Künstlerprogramm.

Lützowstrasse 2

Another repurposed factory space in use at the time, known colloquially as Fabrik (it was subsequently demolished). In June La Barbara led her ‘Voice Workshop’ there, which was a joint venture with RIAS and Radio Free Berlin (SFB) and part of the Insel Musik 2 festival. Photographer Petra Grosskopf documented the event and her images reveal at least seven participants in an open, unfinished industrial space with concrete floors and pillars and a wall of windows on one side. Two Czech visual artists exhibited work in conjunction with the workshop: Rudolf Valenta created an installation focused on the floor, and Jan Kotik's ‘Dreieck-Object’ was on display.Footnote 23

Kurfürstenstrasse 58

There were two important venues at this address, which is the former villa of Henny Porten, a German movie star and film producer of the silent era: the Café Einstein, and the daadgalerie on the floor above it. Café Einstein was a favourite hang-out and a venue for Künstlerprogramm events, such as John Cage performing ‘Writing through Finnegan's Wake’, ‘62 Mesostics re Merce Cunningham’ and ‘45’ Minutes for a Speaker’ that June. The daadgalerie opened above it in 1978 and remained there until relocating to its current home, in Kreuzberg, in 2017. La Barbara's first gig in West Berlin that year was here, in a performance that included the premiere of q-autre petites bêtes (four little beasts) as a sound installation (it was premiered as a performance work for voice and tape that year in Cologne). She took the phrase from Marcel Duchamp's ‘Rendez-Vous du Dimanche 6 Fevrier 1916’, in which he broke the first word after the first letter rather than at the syllable. She released it on the LP Reluctant Gypsy, where she explained that ‘the separation of the word “quatre” and the idea image intrigued me and I created a clearing in my imagination where four strange, dissimilar creatures could meet, converse, make love and war and disappear’.Footnote 24 She elaborates further:

My fantasy included creating a sonic language for each of the beasts, differentiating them from one another: 1. – birds, flutters, trills; 2. – low, rapid language; 3. – click language (inhaled glottal clicks); 4. – high rapid language, all imaginary languages of course. I then arranged their encounters as a quadraphonic soundance, which I define in my journal notations…. ‘q-uatre petites bêtes’ was recorded and mixed in March 1979 at CalArts in Valencia, CA, where I had access to Buchla equipment for spatialization, but premiered at the daadgalerie in Berlin.Footnote 25

Handwritten notes in her Künstlerprogramm file list the tech needs for this event: ‘four speakers, amplifier, mixer (4 channel), 4-track tape deck (4 track in-line), 7½ (19 cm), 15 (38 cm) [reel-to-reel-tape speed], in a quad setup’.Footnote 26

A critic for the West Berlin-based newspaper Der Tagesspiegel seemed dubious about both the new venue (‘a small, empty, bare octagonal room, from which doors lead into other small, empty, bare rooms’) and the installation (‘whispers, quacks, and babbles from various loudspeakers’) but grew quite enthusiastic once the live performance began:

Well, at the end of this sound exhibition the voice phenomenon gives a live performance, begins to wander among the bystanders and emit calls against the walls, against the corners, and tests the acoustics. Then, as at the last Metamusik [1978 festival at which she had performed], she lets the ‘birds sing in her head’, in another piece reveals the changing overtone spectra that can, for example, accrue to a single tone through vowels and coloring, and concludes with a study in descending tones; studies are Joan La Barbara's overall elaborations. And then she leaves the field to the four creatures again. The content of this conversation without words can be imagined by everyone.Footnote 27

The critic remembered La Barbara from her performance of her ‘soundance’ Autumn Signal for voice and Buchla synthesiser in the third and final iteration of the Metamusik Festival, which had taken place at the Neue Nationalgalerie in October 1978. Walter Bachauer curated these massive events, working closely with the Berliner Festspiele, the Academy of the Arts, RIAS, SFB and the DAAD. As Beal notes, ‘luckily for Bachauer (and the Americans involved), the peak of renewed interest in American experimentalism coincided with a peak in subsidized funding for innovative cultural programming in West Berlin’.Footnote 28 La Barbara believes that Bachauer, along with Hans Otte, who was music director at Radio Bremen, were on the jury that invited her to the Künstlerprogramm.Footnote 29

Albrecht-Achilles-Strasse 58

The Hotel Steiner was the site of the Hotel Room Event on 5 May, during which ‘fifteen artist videos were taped in different rooms of the Hotel Steiner’.Footnote 30 The event was organised by Fluxus artist Ben Vautier and Mike Steiner. Steiner was an artist, gallerist and collector with a keen interest in video art; in 1979 the Studiogalerie Mike Steiner (aka Steiner Galerie) moved to this address as well. For the Hotel Room Event La Barbara performed a version of her ‘Performance Piece’, which she describes as ‘a very challenging right brain/left brain work that involves making abstract vocal sound when one is focusing on that and if one begins to analyze what one is doing, immediately verbalizing those thoughts. Mike videotaped my performance, which I called “she is always alone”.’Footnote 31 An anonymous critic raved about it:

She talks about her life, steps dimly into the backlight of the open window, utters those shrill, musical screams for which she is famous, and finally gives a kind of concert, a maenad's voice that hardly sounds human, reminiscent of an instrument or the lament of the Erinyes. The 29-minute ‘she is always alone’ is truly the best thing I've ever seen on video – a complete piece, a work of art.Footnote 32

This video is part of the Mike Steiner Collection of the Nationalgalerie, and it was included in an exhibition called ‘Live to Tape: The Mike Steiner Collection’ at the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum für Gegenwart in 2011–12. A still from La Barbara's video is featured on the museum's site for the exhibition.Footnote 33

Corner of Hardenbergstrasse and Fasanenstrasse

The Hochschule der Künste occupied this large space, just up the street from her apartment. It was established in 1975 as a merger of two extant institutions, the Hochschule für Bildende Künste and the Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst. In 2001 it became the Universität der Künste Berlin. There La Barbara performed Responsive Resonance (with feathers), the first piece she composed in West Berlin, in 1979, as part of the Insel Musik 3 festival on 8 December.

Welserstrasse 25

This was the location of the Arsenal Kino der Freunde der Deutschen Kinemathek. In August the DAAD sponsored a week of programming at the cinema, beginning with a screening of Meredith Monk's Quarry (1976). La Barbara's event on 4 August featured Vermont II and Hunters, two video performance pieces for vocalist in an outdoor environment from 1975, as well as a screening of she is always alone.Footnote 34

Kufsteiner Strasse 69 (Funkhaus am Hans-Roenthal-Platz)

RIAS was located at this address. She worked in the studio here for three days, 18–20 September, recording two works RIAS had commissioned from her: ShadowSong and Klee Alee. (I wondered if, given the Berlin-specific commission, the title of Klee Alee was an allusion to Clayallee, the street in the American sector named after General Lucius D. Clay and the location of the US State Department presence, in the form of US Mission Berlin rather than an embassy, but it is not.Footnote 35) RIAS records do not preserve the details of her sessions (engineers, equipment, studio number), but it may have been Studio 7, identified in 1981 as ‘the only studio for realizing complicated recordings’.Footnote 36 Technicians had begun updating Studio 7 in 1978, collaborating with the local company Georg Neumann to assess needs and identify appropriate equipment. This included items like an autolocator, which ‘can be connected to a multitrack allowing control over different functions of that mixing/recording console as well as a series of automated functions in sound production’, and a compander system, ‘a neologism for compressing and expanding’ that ‘allows communication between analog and digital instruments and audio production settings’. Both were common in radio broadcasting and recording studios at the time of the transition from analogue to digital.Footnote 37

RIAS broadcast her recordings on 3 December, and she premiered them as works for live voice and tape in Paris that October. She writes that ‘both works, conceived, composed and recorded in Berlin, are for multiple voices (all my own) with no electronics other than equalization and placement in the stereo horizon’.Footnote 38 She requested permission from Herbert Kundler at RIAS to release the recordings on her album Reluctant Gypsy. In a letter dated 25 December 1979 she explained her situation.

As you may be aware, the commercial recording companies are not interested in ‘avant garde’ music and so many composers have started ‘independent’ labels, mostly for issuing their own music. I am one of these, having already issued a first record (titled ‘Voice is the Original Instrument’) on my own label, Wizard Records. As I must cover all printing, pressing, and related costs myself, I cannot afford to pay additional costs.Footnote 39

Kundler granted use of the tapes for free up to 2,000 copies sold, after which RIAS would expect 5% of the retail price. He required only that the cover state ‘Production: Radio RIAS Berlin’ and five free copies upon release.Footnote 40 In the liner notes to Reluctant Gypsy La Barbara described the pieces as follows:

‘Klee Alee’ was inspired by a Paul Klee painting which is layered both two- and three-dimensionally; one can look at blocks of color from a distance and at delicately scratched detail on closer inspection. I did not intend to sing the painting but to create a textured piece translating some of the visual elements into sound: thick, blocklike solid colors became repeating melodic units, greens and blues, with delicately curving figures, designs carved into the thick fabric of sound.

‘ShadowSong’ is a threshold experience where concentration is interrupted by shadows at the outer edges of vision and by memories on the periphery of thought. Words float by that are not quite distinguishable, melodies have an ominous quality, shadow/memories compound with resolute persistence until one confronts the decision to go with the shadows or against them.Footnote 41

Given the visual nature of these descriptions it is not surprising that she re-released both tracks in 1991 on the CD Sound Paintings. La Barbara discussed them in that context during her lecture at the Red Bull Music Academy in 2016. ‘Those early sound paintings like “Twelvesong”, “Klee Alee”, “ShadowSong”, “Urban Tropics”, it was a way of translating the visual into sound, and how you use your vocal instrument or other instruments to give a sense of what visual is inside your brain.’Footnote 42

Potsdamer Strasse 50

In the west the Neue Nationalgalerie was frequently referred to as simply the Nationalgalerie, although technically that term applied to the museum in East Berlin. La Barbara recalled many trips to this museum, where an exhibition of paintings by Ernst-Ludwig Kirchner made an especially vivid impression. It ran from 29 November 1979 to 10 August 1980.

The other points on the map are additional venues in which the Künstlerprogramm sponsored events in West Berlin that year. La Barbara may or may not have attended any of them, but they are provided to show the extent of the institution's networked presence in the city.

Blücherplatz 1

The Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek showcased string music by Joji Yuasa and Isang Yun.

Hardenbergstrasse 22

Amerika Haus Berlin hosted a composer portrait of Emmanuel Nunes, as well as the S.E.M. Ensemble playing Cage and LaMonte Young.

Spandauer Damm 22

The Orangerie of Schloss Charlottenburg featured Petr Kotik's music in a concert by the S.E.M. Ensemble.

Potsdamer Strasse 33

The Staatsbibliothek on the Potsdamer Platz was the site of a concert of string music by Nunes.

Hanseatenweg 10

The Akademie der Künste (West) hosted a festival of Hindustani classical music.

Steinplatz 2

The DAAD offices held Daniel Lentz's composer portrait.

Am Rathaus 2

Alt-Schöneberger Saal is a space at the Rathaus Schöneberg where the Berliner Bläsertrio played the music of Charles Boone and Clement Calder.

(A nineteenth venue, the Haus am Waldsee at Argentinische Allee 30, was too far southwest to fit on the map. Literatur und Musik 4 featuring Milko Keleman took place there.)Footnote 43

Of course, La Barbara was not finished with West Berlin after 1979. She took up another long residency there in 1981 when her husband, composer Morton Subotnick, was a Künstlerprogramm guest, and she has returned many times since. If American experimental music comprises a large part of the soundscape of West Berlin, the Künstlerprogramm played a large part in its presence there. The map helps to visualise the music's spatialisation in the city, the distribution of which is largely due to the nodes established by the Künstlerprogramm. My narrow focus also throws into relief the fact that it is La Barbara herself, her voice, whether live or manipulated and multiplied on tape, who reverberated in spaces all over the city. In other words, she constitutes a significant component of the Cold War soundscape – its pitches, decibel levels, timbres, textures, extended techniques and effects.

Acknowledgements

I am especially grateful to Joan La Barbara for taking time to correspond and speak with me, to João Romão for his expertise in 1970s-era electronics and his exemplary archival research when pandemic conditions prevented my own travel to Berlin, to Sabine Blödorn, Archivist of the Berliner Künstlerprogramm, for kind assistance with resources and contacts and to Ryan Wayne Dohoney for guidance and inspiration. Thanks also to Clifford Anderson, Abby Anderton, Amy C. Beal, Andrea F. Bohlman, Benedikt Brilmayer, Connor Gilmore, Jennifer Iverson, Michael Müller and Pamela Potter.