Introduction

Friendship in dementia contributes to well-being, social connectedness, and quality of life (McCabe, Robertson, & Kelly, Reference McCabe, Robertson and Kelly2018); however, people who have been diagnosed with dementia are at increased risk of social isolation (National Seniors Council, 2014). This elevated risk is caused, in part, by the stigma that accompanies the diagnosis, and results in the loss of social connections (Harris, Reference Harris2011, Reference Harris2013; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, Robertson and Kelly2018). Society’s lack of understanding about dementia contributes to stigma and results in experiences of isolation and loneliness by individuals living with dementia (Sabat & Lee, Reference Sabat and Lee2011). Nevertheless, people with dementia wish to remain engaged with family and community, and they experience meaning in doing so (Beard, Knauss, & Moyer, Reference Beard, Knauss and Moyer2009; Dupuis et al., Reference Dupuis, Whyte, Carson, Meschino, Genoe and Sadler2012; Genoe & Dupuis, Reference Genoe and Dupuis2014). Indeed, MacRae (Reference MacRae2011) argues that with sufficient support and resources, people living with dementia can continue to lead meaningful and purposeful lives. She further suggests that supportive relationships may lessen dementia’s negative impact on quality of living. Despite the importance of social support and social engagement for people living with dementia, little is known about how friendships are maintained after a diagnosis. The purpose of this article is to explore the strategies that people living with dementia and their friends draw upon to sustain such a friendship.

Literature Review

Although research exploring friendship in dementia is limited, extant literature provides insight into the experience of friendship after diagnosis. In this literature review, we explore how dementia-related stigma may impact friendships. Then we discuss the meaning and role of friendship after a diagnosis of dementia.

Stigma refers to devaluing of individuals based on particular characteristics, thereby preventing them from full participation in society (Goffman, Reference Goffman1968). It can lead to negative labelling, loss of status, and negative stereotypes (Link & Phelan, Reference Link and Phelan2001). Research has shown that people living with dementia experience stigma as a result of their diagnosis (Benbow & Jolley, Reference Benbow and Jolley2012; Milne, Reference Milne2010). Stigma can occur at multiple levels, ranging from self-stigma, whereby the person with dementia internalizes negative beliefs about dementia and chooses to reduce social contact (Milne, Reference Milne2010; Milne & Peet, Reference Milne and Peet2008; Swaffer, Reference Swaffer2014), stigma that impacts not only the person with dementia but also their family care partners (also known as courtesy stigma, Goffman, Reference Goffman1968) who may not receive appropriate supports, and stigma that occurs at the health care service provision and policy levels, thereby impacting what services people with dementia have access to and how those services are delivered (Benbow & Jolley, Reference Benbow and Jolley2012).

Stigma associated with dementia and resulting negative emotions may lead to exclusion of people with dementia from everyday life, increasing their feelings of social isolation (Burgener, Buckwalter, Perkhounkova, & Liu, Reference Burgener, Buckwalter, Perkhounkova and Liu2015; Burgener et al., Reference Burgener, Buckwalter, Perkhounkova and Liu2015; Zeilig, Reference Zeilig2013). Indeed, the “tragedy discourse of dementia” (Mitchell, Dupuis, & Kontos, Reference Mitchell, Dupuis and Kontos2013, p. 2) holds that when an individual is diagnosed, they no longer experience meaning in life and are instead “turned into the living dead” (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Dupuis and Kontos2013, p. 2). This discourse leads to loss of self-worth as well as feelings of shame, guilt, isolation, and abandonment among people who are diagnosed with dementia (Earnshaw & Quinn, Reference Earnshaw and Quinn2011; MacRae, Reference MacRae2011). As such, diagnosis can have a negative impact on relationships, including decreased interaction and involvement with family and friends as well as social withdrawal and isolation among those diagnosed with dementia (Powers, Dawson, Krestar, Yarry, & Judge, Reference Powers, Dawson, Krestar, Yarry and Judge2016; Wawrziczny, Antoine, Ducharme, Kergoat, & Pasquier, Reference Wawrziczny, Antoine, Ducharme, Kergoat and Pasquier2016). Often friends who find it difficult to witness changes resulting from dementia withdraw from the friendship (Harris, Reference Harris2013). Yet, friends comprise an important component of one’s support networks following a dementia diagnosis (Fortune & McKeown, Reference Fortune and McKeown2016; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, Robertson and Kelly2018; Ward, Howarth, Wilkinson, Campbell, & Keady, Reference Ward, Howarth, Wilkinson, Campbell and Keady2011). Mutually rewarding friendships may become more meaningful following a diagnosis of dementia, particularly in the face of stigma associated with the disease (Sabat & Lee, Reference Sabat and Lee2011).

Some researchers have explored notions of “befriending”, or “facilitated friendships”, where volunteers are paired with people living with dementia in an effort to build positive relationships (e.g., Phillips & Evans, Reference Phillips and Evans2018; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Howarth, Wilkinson, Campbell and Keady2011). Others have considered development of friendships among people with dementia living in long-term care (e.g., de Medeiros, Saunders, Doyle, Mosby, & Van Haitsma, Reference de Medeiros, Saunders, Doyle, Mosby and Van Haitsma2011). However, little is known about how friendships are sustained when one friend has been diagnosed with dementia (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Howarth, Wilkinson, Campbell and Keady2011). Ward et al. argue that a better understanding of friendships among people with dementia is needed (see also, Harris, Reference Harris2013).

Harris’s (Reference Harris2011, Reference Harris2013) research on long-term friendship provides some insight into friendship and dementia. Through interviews with people living with early stage dementia, Harris (Reference Harris2011) found that there was a need for “meaningful social connectedness” (p. 308) and that friendships continue to be important following a diagnosis of dementia. When people living with dementia were valued and respected as persons by their friends, these friendships were particularly meaningful. Furthermore, Harris (Reference Harris2011) noted that friendships were beneficial for both parties, and that relationships were reciprocal. Additionally, recognition of strengths and limitations helped to sustain friendships.

In a subsequent study, Harris (Reference Harris2013) conducted focus groups with persons living with dementia and their care partners, followed by interviews with friends. Findings indicate that whereas some friends feel uncomfortable, other long-term friends demonstrate commitment to the relationship after diagnosis. They focus on the person with dementia as a friend rather than focusing on the diagnosis. These friendships display loyalty, reciprocity, and acceptance. Similarly, MacRae (Reference MacRae2011) interviewed people living with dementia who felt supported by friends. Participants in her study continued to engage in meaningful activities while spending time with friends.

Perion and Steiner’s (Reference Perion and Steiner2017) study exploring reciprocity provides additional insight into the value of friendships for people with dementia. They identified ways that friendship had meaning for their study participants who had been diagnosed with dementia. First, participants acknowledged that the length of the relationship was important. Long-time friends were not only able to provide support, but also had shared history that contributed to feelings of trust. Second, reciprocity was deemed important and people with dementia valued having a meaningful role in the lives of their friends. Third, reciprocity led to “feeling alive” (p. 9), because helping others was a way to show appreciation as well as to experience a sense of purpose. Further, receiving help led to positive feelings and a sense of appreciation. Fourth, participants felt reassured that they could call on friends for assistance if needed. Finally, participants sought out security through friendship and reported that disclosing their diagnosis did not lead to loss of friendships.

Research suggests that people living with dementia benefit from and continue to value meaningful, reciprocal relationships with their friends. However, how both people with dementia and their friends maintain these friendships is unknown.

Methodology

Epistemology

In keeping with the growing body of research that aims to understand the experience of dementia from those who are experiencing it, we followed a constructivist epistemology to better understand how friendships are maintained after a diagnosis of dementia. Constructivism focuses on meaning-making among individuals, while acknowledging that each person’s experience is unique. Constructivists believe that there are many ways of making sense of the world, and that each way of doing so is valid (Crotty, Reference Crotty1998). As such, constructivism holds that knowledge is co-constructed and subjective (Lincoln, Lynham, & Guba, Reference Lincoln, Lynham, Guba, Denzin and Lincoln2011). Constructivists acknowledge that multiple meanings exist and that these meanings are constructed through interactions with others (Creswell & Creswell, Reference Creswell and Creswell2018; Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Lynham, Guba, Denzin and Lincoln2011). This epistemology was best suited for this research because it led to insight into how people living with dementia, their friends, and in some cases, their family members, make sense of their experiences of friendship. We adopted this approach to both honour and understand the experiences of people with dementia and their friends, and to co-construct knowledge regarding sustaining friendship after diagnosis. Furthermore, we wanted to explore the social processes and social meanings involved in maintaining friendships.

Theoretical Framework

This study was guided by socioemotional selectivity theory (SST) (Carstensen, Reference Carstensen and Jacobs1993, Reference Carstensen1995). SST suggests that as people age, or when they face significant health concerns, they focus on close relationships with a small number of familiar people, including family members and long-standing friends. SST suggests that older adults seek emotional support from a small number of other people rather than from a large social network. Doing so helps to increase the benefits obtained from these close relationships while reducing social and emotional risks (Lansford, Sherman, & Antonucci, Reference Lansford, Sherman and Antonucci1998). As a result, a select few friendships may become increasingly important after a diagnosis of dementia.

The relational citizenship model also lends insight into this study. Relational citizenship embraces embodied selfhood, interdependence, reciprocity, and active engagement in care among people with dementia, as necessary for experiencing citizenship (Kontos, Miller, & Kontos, Reference Kontos, Miller and Kontos2017; Miller & Kontos, Reference Miller, Kontos, Andreassen, Gubrium and Solvang2016). Relational citizenship builds on social citizenship (Kontos & Grigorovich, Reference Kontos and Grigorovich2018), whereby people living with dementia have the right to be free from discrimination and have opportunities to engage in life and experience growth (Bartlett & O’Connor, Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010).

Constructivists typically draw on qualitative methodologies to conduct research (Creswell & Creswell, Reference Creswell and Creswell2018; Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Lynham, Guba, Denzin and Lincoln2011). Therefore, we adopted an inductive, qualitative approach to data collection and analysis. Data were collected through individual, dyadic, and group interviews with people who were living with dementia, their friends, and in some instances, their family members. In the next section, we describe our participant recruitment, data collection, and data analysis processes.

Participant Recruitment

In order to participate in this study, friends must have known each other for 2 years or more prior to a diagnosis of dementia. Although we had initially required participants to have been friends for at least 5 years, we reduced the length of time in order to increase the number of potential eligible participants when recruitment proved challenging. Participants were recruited through community-based dementia support services as well as through assisted living and long-term care facilities. We shared our study information with these services and facilities, which then provided the information to potential participants they believed would be interested in participating in the study. These potential participants contacted us by telephone or e-mail to learn more about the study. We then explained the study procedures in detail and asked if they were interested in participating. If participants indicated that they were interested, interviews were then scheduled. In addition, some potential participants contacted Dr. Genoe after reading about the study in a local newspaper. Again, Dr. Genoe provided more information about the study to these participants and scheduled interviews when they agreed to participate in the study. Interestingly, the most common reason given for not participating in the study was that friends were no longer in contact.

We initially set out to conduct dyadic interviews with the friends together. However, participant recruitment proved more challenging than we anticipated. Therefore, we took a flexible approach to data collection in order to provide a comfortable and accommodating environment for participants. Several participants opted for individual or group interviews instead of dyadic interviews. We conducted 10 individual interviews, 11 dyad interviews, and 2 group interviews. The two group interviews occurred when a friend who was diagnosed with dementia had a group of close friends who spent time together and provided support. In these instances, the friendship groups requested to be interviewed together. In both cases, the person with dementia was present during the interview.

Furthermore, as several family members expressed an interest in participating, we expanded our inclusion criteria to include family members. Although family members may have different perspectives regarding friendship in dementia, we chose to include them and found their perspectives to be valuable. Their observations and experiences as family care partners highlighted some of the nuances of friendships that may have been difficult to capture from individual interviews. Family members were able to expand on details of friendships and time spent with friends when the person with dementia may have forgotten some of those details. Additionally, in many cases, including family members helped to create a comfortable environment for the participant who was living with dementia. In most cases, family members (e.g., spouses, adult children) took part in interviews with their loved one with dementia. Two adult daughters, who both acted as power of attorney for their fathers, who were close friends, were interviewed without their loved one present. One daughter’s parent with dementia had died during the study. A second adult daughter was unable to schedule a time to be interviewed with her father, who resided in long-term care. In both cases, the daughters were able to add a great deal of context that helped us better understand their fathers’ friendship with one another and how they were able to remain friends after diagnosis.

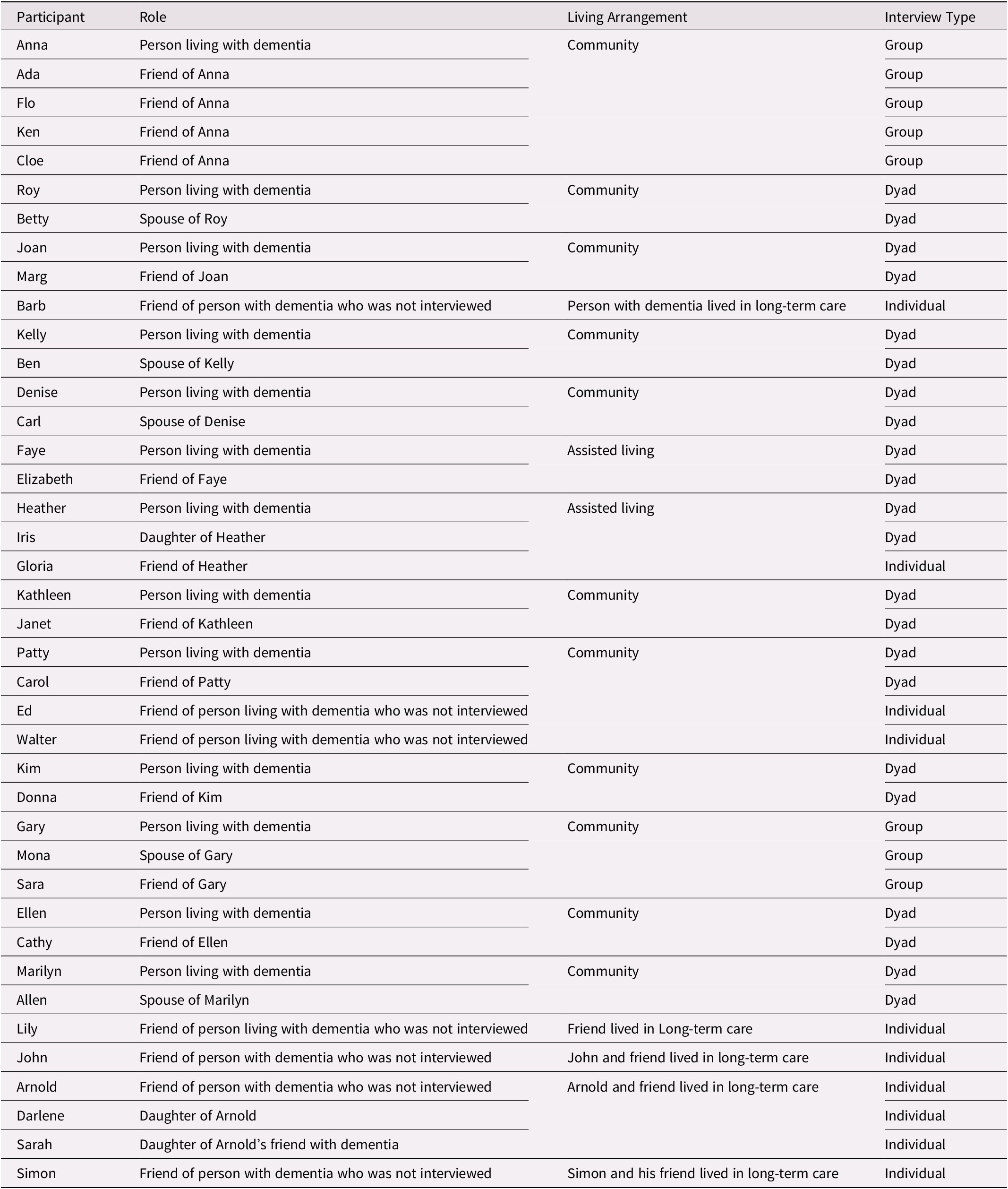

We interviewed people who were living with dementia (n = 13), friends (n = 19), and family members (n = 8) (see Table 1). In order to understand how, if at all, friendship changes over time, we aimed to recruit people with dementia and/or friends who were living at home, living in assisted living, and living in long-term care, and who were at various stages of dementia (e.g. mild, moderate, and severe) to better understand how friendships are sustained at different stages of dementia. While most participants who were diagnosed with dementia were living in the community (n = 11), two resided in assisted living facilities, which provide support for residents who do not require full time nursing care. Although we were unable to recruit individuals living with dementia who resided in long-term care homes, we interviewed three friends and two family members of long-term care residents. Friends were required to have known each other for at least 2 years to participate in this study, however, friendships ranged from 2 years to more than 30 years in length. The majority of participants had been friends for more than 20 years, and only one friendship was 2 years in length.

Table 1. Participants

Data Collection

Interviews were conversational in nature and focused on the friendship, from its beginning until the present, as well as on its meaning. Following a semi-structured, open-ended interview guide, we asked participants the following questions: How long have you been friends? What does your friendship mean to you? Please describe any changes to your friendship since receiving a diagnosis of dementia. What do you consider to be challenges to maintaining your friendship? What do you most enjoy doing together? We also asked participants to identify strategies for maintaining friendships (e.g., If asked by others for strategies to maintaining friendship after a diagnosis of dementia, what would you tell them?). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim and ranged in length from 30 minutes to 2 hours.

Ethics approval was obtained from each author’s institutional research ethics board before the study commenced. At the beginning of each interview, written informed consent was obtained from participants. Each participant was provided with an informed consent form and the interviewer and participants reviewed the form together. In cases in which participants living with dementia had a power of attorney, informed consent was provided by the power of attorney and verbal assent was obtained from the participant. In the case in which one adult child was interviewed without her father, the father provided assent for the daughter to be interviewed alone. Pseudonyms have been provided to protect confidentiality for the participants of the study.

Data Analysis

We utilized Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) approach to thematic analysis. Braun and Clarke identify six steps of thematic analysis. First, we familiarized ourselves with the data by reading transcripts several times. This allowed us to get a sense of the data as a whole. Second, we hand-coded each transcript, making note of initial codes in the margins of the transcripts. Third, we searched for themes by collating codes into groups and subgroups. In this stage, we listed all of our initial codes and then grouped them together based on similarities and differences. Each group of codes was given a name. We then compared these groups with one another and combined those that were similar into a smaller number of themes. For example, our initial codes such as going with the flow, accepting that things are different, and adjusting to the individual’s ability were grouped into the subtheme of being accepting of change. Our initial codes of keeping in touch, visiting, and sticking together were grouped into the subtheme of checking in with each other. Once our initial codes were combined into themes and subthemes, we engaged in step four, in which we reviewed the themes and their subthemes and considered how they contributed to the whole story of the data. Fifth, we defined the themes and subthemes by writing a brief description of what the theme referred to, relating them back to the research questions. Finally, in step six, we interpreted the individual themes by providing quotes from the participants.

Findings

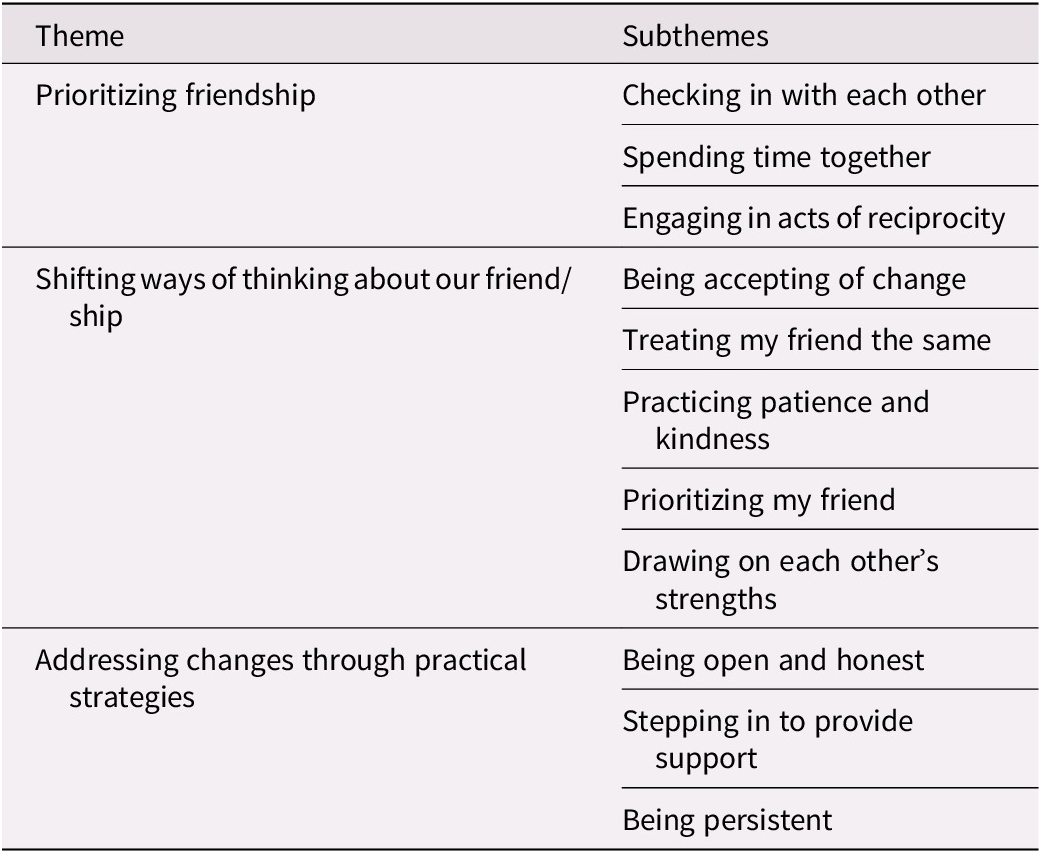

Through our data analysis process, we generated the overarching theme of adapting to change. Participants sought ways to manage changes to their relationships that occurred as a result of memory loss. They worked to adapt and continue to nurture their friendships rather than give up on them. Three themes related to strategies for maintaining friendship through the changes that occurred as a result of dementia were generated. Themes include: (1) prioritizing friendship, (2) shifting ways of thinking about our friend/ship, and (3) addressing changes through practical strategies. These themes and their subthemes are explored in Table 2.

Table 2. Themes and subthemes

Prioritizing Friendship

Prioritizing friendship was vital for adapting to the changes that occurred as a result of memory loss. It refers to participants’ efforts to nurture their friendships and ensure that ties are not broken in the face of a great deal of change. Participants identified several ways of prioritizing friendship, including checking in with each other, spending time together, and engaging in acts of reciprocity.

Checking in with each other

People living with dementia and their friends periodically checked in with each other. These simple acts of maintaining contact, such as regular phone calls or dropping in for a visit, enabled the friendship to continue to flourish. Checking in with each other allowed participants to balance busy schedules with opportunities for connection in between longer visits. Kathleen (friend living with dementia), reflected on the regularity of keeping in touch with Janet.

But we don’t talk every day, you know, but probably within two weeks we would touch base, or if Janet needs something or we want to go to something, we go to it. You know, I’m busy with my family and she’s busy with hers. So, but I don’t think a month would go by and we wouldn’t touch base…

With this quote, Kathleen emphasizes the ongoing and supportive nature of their relationship. Although both friends have multiple demands on their time, they make sure to connect with each other on a regular basis. Similarly, Faye, who was living with dementia in assisted living, noted the importance of keeping in touch with her friend, who lived in the same facility.

Trying to keep in touch. If I haven’t talked to her in a bit, then keep in touch see how things are going. Trying to keep in touch to some degree. We maybe can’t exactly every day. Sometimes things come up with either her family or my family …but we try and keep in touch periodically so that we don’t lose touch with each other.

Although Faye and Gloria lived in close proximity to one another, they continued to value the small act of keeping in touch with one another even when other relationships and opportunities arose that limited their opportunities to spend time together.

Likewise, Donna highlighted her intention to stay in touch with her friend, Kim. This intention was, in turn, appreciated by Kim, who recognized that continued friendship is not always possible.

Donna: I respect her life and I know she’s busy, but as the year will go by and as long as I stay here and she stays here in [town], my intention is not to lose her, to stay in contact.

Kim: That’s nice to know, ‘cause some people are bound to wander off.

In this exchange between Donna and Kim, Donna expressed her desire to maintain contact by keeping in touch, and Kim found comfort in knowing that Donna would stand by her as dementia progressed, whereas other friends might not. In this study, ensuring regular contact between friends, even if it was periodic, served as a means of prioritizing a meaningful friendship despite a diagnosis of dementia. Participants valued the act of checking in, as they acknowledged that not all friendships were strong enough to withstand the changes that dementia would bring.

Spending time together

In addition to maintaining contact with one another, participants recognized the importance of spending time together in meaningful ways in order to stay connected. Although spending time together is a hallmark of any friendship, for our participants, it was particularly valued as a means of creating a sense of normalcy and escape from dementia as they focused on other aspects of daily life.

… we need to socialize and go out once a month, and still do things, but don’t push me out because it’s not contagious. You’re not going to get it, but you could be my support, one of my supports. (Sara, friend living with dementia)

Sara emphasized the importance of doing things together to maintain the support system that she needed. The simple act of going out for coffee could make a difference: “Really try to keep that friendship. It’s so important. And she might not understand you, wholly, but that’s OK. You don’t have to go and talk about dementia. You just go for coffee and talk about the family” (Sara). For Sara, the importance of her friendship lay in the opportunity to experience the simple pleasure of connecting. Similarly, Cloe (friend) spoke about cherishing simple joys that help to facilitate spending time with her friend: “I just love being in her presence still. It doesn’t really matter. Sitting and having a cup of tea with her, or coffee or whatever.”

Faye and Gloria lived in the same assisted living facility, which allowed them to be spontaneous in the time they spent together. When asked how their friendship had changed, Gloria (friend) stated:

I guess because we’re in the same place, we see each other oftener, so I guess our friendship has grown…here we can pop into our rooms, and we do it any old time, and that’s what I call a friendship if you can just do that…and be at ease with that.

Faye and Gloria were unlike other participants because their living arrangement enabled the flexibility to spend more time together. For others, spending time together had to be planned. Lily, whose friend with dementia had moved into long-term care, stressed the importance of creating a routine in order to stay connected: “Maintain a routine. Visit at least once a week and do the same thing each time. Treat [people] with respect and care.” When friends spent time together engaging in simple pleasures, whether spontaneous or pre-planned, they demonstrated the value of the friendship with each other and its priority in their lives and, in doing so, created space for sustaining the friendships over time.

Engaging in acts of reciprocity

In addition to spending time together, reciprocity was acknowledged as a key aspect of prioritizing friendship. Participants valued the meaningful contributions that their friends made in their lives. They drew on each other’s strengths to support one another. For example, Janet talked about her ability to rely on Kathleen.

I always think like Kathleen is there for me. If I was in a desperate situation, I would call her. Now maybe she couldn’t respond right away. But you know, I had two major surgeries in 2008 and I decided when I came home that I should get LifeLine…I asked Kathleen “would you be the one that responds?” There was no question.

Later in the interview, Kathleen described how Janet helps her: “Well, I think Janet, she sees that I’m going off track…her memory is better than mine. So I’ll miss things and she’ll say we did this or we did that…” Janet responded by stating: “She’ll phone if she needs something and if I need something, I’ll phone. I wouldn’t say we see each other every week though or anything like that but she’s there”. This exchange highlights how Janet and Kathleen draw on support from each other and in turn, how they upheld the reciprocity of the relationship after diagnosis. Staying connected by keeping in touch and valuing each person’s contribution to the friendship were key strategies in our participants’ lives for withstanding changes in order to sustain friendships.

Shifting Ways of Thinking about Our Friend/Ship

In addition to prioritizing friendship, participants reframed their friendships and drew on emotional strategies to sustain them. Friends without dementia adjusted their ways of thinking about both the relationship and their friend in order to sustain the relationship. Friends without dementia recognized the changes and learned to accept them without judgment. This involved accepting their friend as they were, while also treating them the same as they had before. Furthermore, it involved practicing patience and kindness, prioritizing their friend over their own feelings, and drawing on the strengths that their friend possessed.

Being accepting of change

Accepting the changes that were occurring within the friend who was diagnosed with dementia was an important reframing strategy for maintaining the friendship. Acknowledging that changes caused by dementia may alter interactions with one’s friend and being able to adjust to the individual’s ability and perspective were necessary to being able to accept the changes. During their joint interview, Janet talked about the importance of being accepting: “I think you just have to accept, you know, none of us are perfect and we accept what may be, might irritate us a little bit….It’s not important in the big scheme of things.” Similarly, Arnold emphasized the importance of accepting his friend as he was, without judgement:

Well, I would say, you know, don’t be critical of the person. Take it in stride and just say that’s the way it is and nothing you can do about it and just be satisfied. I’m satisfied the way [my friend] is ‘cause, you know, he looks good.

Sara (friend living with dementia) spoke about being accepted in her workplace despite fears of losing friendships once a diagnosis was disclosed.

Again, it’s the fear of people shying away from you if you tell them, “I have dementia” or Alzheimer’s, and you’re afraid that they won’t be friends anymore. But I have told my people that I worked with. It took me about two years or three to do so, and there was no problems. They accept me the way I am.

Sara’s comment reflects her awareness of and concern about the stigma related to dementia. Although she initially hesitated to share her diagnosis for fear of losing friends, she found that her work friends were, in fact, accepting of her, which helped her to remain friends with them.

Others demonstrated acceptance by letting things go and not getting upset by changes in behaviour or knowledge.

And the other thing I think that happens is that if you know that, and Patty says something [that is incorrect], sometimes it’s not worth correcting…And really, what does it matter? Like, yeah, whether we did that yesterday or whether we did it Tuesday…who cares? …you don’t correct, correct, correct all the time because then you do feel stupid, and it’s not stupid. (Carol, friend)

Acceptance was more likely to happen when friends did not dwell on the changes. In the middle and later stages of dementia, acceptance was more challenging, because changes were more pronounced. Cloe (friend) stated:

I guess to be there and just not be discouraged by, you know, if she doesn’t know who you are. To not let that crush you, because I think it’s crushing to people to—you know, you have such a strong friendship and to have it not reciprocated, in a sense, I think you’re right that some of her closest friends are so devastated by that, that they just can’t be there. I guess to somehow still be there even though you’re not getting what you wished you could get.

Cloe highlighted important aspects of learning to accept a friend with dementia as they were currently, and living in the moment. Reminding oneself that the friendship was still valuable even though it had changed was an important part of accepting one’s friend. Similarly, Gloria (friend) learned to accept that her friend Faye would forget about their previous conversations or visits: “Sure, let her come for a visit, but she doesn’t remember that we visited. It used to bother me, but it doesn’t anymore. I know she can’t help it.”

Although accepting one’s friend as they were could be challenging at times, friends created a non-judgemental space in order to nurture their relationships despite the challenges that they were experiencing. They remained positive about their relationships and held their friends in high regard, even when cognitive changes impacted communication and behaviour. Closely related to accepting one’s friend was treating them the same as before the diagnosis.

Treating my friend the same

Although memory changes impacted the lives of participants who were living with dementia, they wished to be treated the same as they had been by their friends before the diagnosis, and their friends honoured that preference. When asked what strategies she would recommend for maintaining a friendship after diagnosis, Faye (friend living with dementia) stated: “You try and keep them the same to some degree. You don’t want to change them too much. Because you’re familiar with each other, the way you got to know each other.” Similarly, Faye’s friend, Gloria, reported that she tries to treat Faye the same as she would anyone else, even when she feels frustrated by Faye’s memory loss: “Well, I just sit here and listen to [repetitive stories] and try to have some input about my incidents and my family when we talk about family…I just treat her as if anybody else was talking to me.” Similarly, Kelly (friend living with dementia) reported that she was treated the same by her friends, which she valued: “I don’t know. They don’t seem to act different towards me…At least, I haven’t noticed it. You know, so far it’s been okay, I think.”

Carol (friend), emphasized the importance of upholding respect and dignity. Doing so allowed for better communication between friends and reduced the worry of accidentally offending or hurting a friend’s feelings.

… you have to keep the person’s dignity and respect at all times and that is important for everybody no matter who we are, what we’re doing. Respect is huge…And you don’t feel offended if you’ve forgotten something and you shouldn’t feel upset because you’ve forgotten something. (Carol, friend)

Cathy emphasized the importance of treating someone who has been diagnosed with dementia the same as before, noting that other diagnoses do not lead to changes in friendships.

I would say just go on like you always have. It’s still the same person. You treat them and talk to them just like you always did. And then you don’t really notice an illness, but I would say for people not to be afraid because it’s still that person…It’s like anything else. I mean I have diabetes. You wouldn’t stop being my friend ‘cause I’m a diabetic. …You don’t treat anybody different because they have – just treat people like you always did.

Similarly, Ada (friend) understood the importance of reminding herself that despite the changes related to the diagnosis, her friend is the same person she has always been: “I keep telling myself, it’s her all the time. No matter what, she’s Anna. Anna is Anna. Forgetting or not, she is the same person.” Participants placed value on treating friends the same, which may have served to mitigate the stigma related to dementia. By doing so, participants rejected the tragedy discourse related to dementia. They did not perceive their friends as diminished in any way, and viewed their friends with dementia as friends, first and foremost.

Practicing patience and kindness

Although participants emphasized the importance of treating one’s friend the same following a diagnosis of dementia, they also responded in different ways and adapted their behaviour to accommodate changes in cognition. Carol (friend), spoke about having to slow down.

And I think I said to you, “You know, if you broke your leg, we wouldn’t ask you to run. If your brain’s not working quite as fast, we’re not going to ask you to keep up. We’re going to give you the pathways to get through it.” And I think we have to remember that about people who, you know, your brain isn’t firing as fast as it once did. Well, then, let’s slow it down.

Slowing down was a useful strategy in the early stages of dementia, however, more accommodations were needed in later stages of dementia. For example, friends of people with dementia practiced patience when conversations became repetitive.

I would say that I try not to be different than I’ve always been except I try to, at the same time, be far more patient. I’m quite willing to listen to the same story time and time again as if it’s a new story to me. (Walter, friend)

Later in the interview Walter emphasized that kindness was needed when conversations did become repetitive, even if it was not always easy.

Four or five minutes later [friend living with dementia] said, “And how is Max?” And [the] answer was, “Well, he’s still dead.” That’s humourous, but at the same time, you know, the easier answer was to say, “Max passed away a few months ago.” As if he’s hearing the question for the first time. I think that’s kinder. It’s not always easy to do that…

Here, Walter highlights that even when conversations become frustrating or irritating for friends without dementia, it is important to continue to make the effort to practice kindness instead of resorting to hurtful or unkind responses. By selecting words carefully, patience and kindness served to honour a friend who was experiencing memory loss and where that person was in their journey, rather than belittling them for their cognitive changes.

After moving into long-term care, friends continued to make accommodations in response to changes in cognition. John (friend) told us about taking his friend with dementia to the dining room in the long-term care home where they both lived. John used positive language and encouragement when his friend did not recognize the dining room where they frequently ate.

…but there were only those moments where I would say, “We’re going to go down and have dinner or lunch at our favourite place.” And she’d say, “Where’s that?” And I thought, “Well, I’m not going to say. ‘You know where it is.’” I’d say, “You’ll really like it.” So when we got down to the – on the elevator and down to that floor and we’d come out, she looked and said, “I’ve never been here before. I don’t know of it.” And I said, “Doesn’t matter. You’re going for dinner. Come on. You’ll really love it. It’s your favourite place.” (John, friend)

Sidney, an adult daughter, told the story of how her father responded to his friend with dementia whenever that friend mentioned going on a trip after moving into long-term care. Her father recognized that his friend’s reality was different from his own and adjusted his responses accordingly instead of correcting the friend.

So we’d go and Bill would say, “I’m leaving for a cruise around the world next week. Do you want to come?” And my dad would say, “Sure.” And then he’d say, “Okay, well, you need to bring this. Don’t bring any clothes ‘cause I’ll buy you new clothes.” And it was fine. It was good. And then the odd time, my dad would show up and [Bill would] give him hell. And he’d say, “Were you in the brink again for breaking curfew?” And my dad said, “Oh yeah, I didn’t get to bed on time last night. I was out on the town.” You know, he would play along with him. But at first, my dad wasn’t sure how to do it. But the nurses were great in guiding him, saying, “Yeah, just go with it.” You know, there’s no sense in telling him it’s not real, ‘cause that was his world.

Again, use of careful and positive language was an important strategy for sustaining friendships. Both of the previous quotes demonstrate how friends used communication to convey their acceptance of cognitive changes and a willingness and desire to support their friends and to create a comfortable and safe space for friends to be themselves, without judgement, as dementia progressed.

Prioritizing my friend

As friends accommodated changes, they shifted their ways of thinking about the friendship by prioritizing the needs of their friend over their own needs or preferences, even when they felt grief or a sense of loss as a result of the changes that dementia brings. “So it’s more about our pain, but in a way that’s irrelevant. It’s not about us. It’s about her” (Flo, friend). In the same group interview, another friend stated: “She’s still there. She’s still there. No matter what she does. So, just get over yourself” (Cloe, friend). These comments reflect recognition among this group of friends that their needs and reducing their own discomfort were less important than caring for their friend. Therefore, they set their own feelings aside in order to sustain a friendship that was meaningful to them. Similarly, Ed (friend), stressed that the needs of his friend with dementia were greater than his own, and that it was important to prioritize them: “It’s not about me. This is about [my friend who is living with dementia] and his wife. I can’t see it happening with our group [that] all of a sudden we’re going to stop doing this, unless it becomes unsafe.”

Drawing on each other’s strengths

The final aspect of shifting ways of thinking about the friendship involved drawing on each other’s strengths. Focusing on strengths and abilities rather than on losses allowed for a mutual exchange of support. The following conversation between Kathleen and Janet shows how each drew on the other’s strengths so that they could attend the symphony together.

Janet: Well I know, Kathleen was having trouble the last couple of years with the symphony tickets, right? Like because she used to have them before me. But this year, she said, “You should keep them.” You recognize that I can – you can do lots of things better than me as far as mobile, but I can do better memory things than you. (laugh)

Kathleen: That’s right.

Janet: So you know, you see the 2 of us –

(Mutual laughter)

Kathleen: But when I bought the tickets, I didn’t want to put them somewhere and forget where I put them.

Janet: I try not to make a big issue of it, because she doesn’t make a big issue when I can’t go somewhere so I don’t make a big issue when she can’t remember something.

Janet’s mobility impairments led to reliance on Kathleen for transportation, because Kathleen was still able to drive safely, but Janet took responsibility for looking after the tickets. By relying on each other’s strengths, they were able to continue to spend time together enjoying their mutual interests.

Even when friends experienced more advanced stages of dementia, their friends without dementia continued to focus on and honour their strengths. Ed focused on his friend’s long-term memory and sense of humour.

Well, I’ve always enjoyed [my friend] and there’s still a sense of humour…Just the fact that he’s right there and enjoying his beer and always mentions, “Oh, yeah, I remember all the good times we used to have,” and then we’d talk a little bit about that.

Flo, a friend who sometimes assists with physical care, similarly drew on Anna’s love of music to complete activities of daily living.

Music, her brain still works so good with music. Like if I’m showering her and I’m singing something, she would catch the melody, rhythm and she’s humming with me and following. So her brain’s still good with music.

Similarly, Sidney (adult daughter), told us how her father supported his friend with dementia by focusing on their shared history, which provided opportunities for drawing on a variety of long-term memories that were meaningful to both.

… my dad could read the reality in it, right? So when Bill would say to my dad, “We’re going to Florida.” My dad could see that was really Bill talking about the good times they had in Florida. So he would then start to talk about, “Hey, do you remember when we’d go to Woody’s? Do you remember the grocery store? Do you remember your trailer?” And Bill would say, “I didn’t live in a trailer! I lived on the water.” And my dad would say, “No, I lived on the water. You had a trailer.” So my dad could really read that when we taught him to and really helped Bill go back to the real world. And he used it in a grounding way, very sweet, you know? And so Bill would get dressed up for Remembrance Day and my dad would say to him, “Remember when we had the dinner dances at the Prince Hotel? Remember when we marched in the Warriors Day Parade?” My dad would always ground it back to what they had done.

In each of these examples, shared history and common interests led to recognition of and appreciation for each other’s strengths. When strengths were acknowledged, such as a sense of humour or ability to retain long-term memories, friends were able to encourage using these strengths, thereby enhancing their enjoyment of the time spent together, which may have served as a motivator for viewing the friendship in new ways and making the effort to sustain it. By drawing on strategies such as acceptance, treating friends the same, prioritizing the person with dementia, and drawing on each other’s strengths, participants of this study were able to sustain their friendships. In addition to reframing the friendship, participants identified several practical strategies, which will be explored next.

Addressing Changes through Practical Strategies

Practical strategies adopted by participants included being open and honest, stepping in to provide support, and being persistent. Each of these strategies seemed to help the person with dementia live more comfortably with the diagnosis and assist friends in finding ways to continue spending time together.

Being open and honest

Participants felt that honesty with each other about memory loss was vital for sustaining friendships. They were open about their diagnosis and their needs. Ben (spouse), highlighted how being open was beneficial for his wife.

We’re both very open to letting them know that Kelly has a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and so on…while we were in [a] coffee shop for an hour [visiting with a friend and] talking and Kelly seemed kind of vacant on some of the things, “This is the problem. Don’t think she’s become a snob.” Of course, I shouldn’t have had to say that to [our friend] because she said, “Well, I would never think that.”

Being open about the diagnosis enabled participants to explain changes in behaviour and memory. Carol (friend) encouraged her friend Patty to be honest about her diagnosis as well

One of the things I said to Patty when we went to the family doctor…“This is hard, and I know one of the things I would really strongly suggest is you tell your friends. You tell people.” Because, with me, if I call and ask you something and then you don’t respond, or I leave a message and don’t call, I’m going to assume you don’t want to be with me. I’ll assume you don’t want to do that. But if you forget, that’s different….So if you tell them, and you did, and I think that made a big difference with some people.

Kim noted that being honest provided a sense of comfort and of not having to worry about judgment from friends, who then understood that changes were the result of the diagnosis.

And then you’re not asking for forgiveness all the time. If you do something silly, everybody blames it on the Alzheimer’s (laughs)…the idea of not letting people know right away puts you in an uncomfortable position ‘cause then you’re always trying to hide it.

Honesty about a diagnosis of dementia provided a sense of comfort about asking for help when needed. Kathleen (friend living with dementia) stated:

You just have to lay it on the table and ask the questions. You can’t pretend, you know, that you know something when you can’t pull it out of your head. So I’m just very relaxed because if I need to know something, I’m going to ask or I’m going to tell somebody I forgot. It’s just not something you can deny. And I don’t find it that bad.

By sharing the diagnosis with her friend and with others, Kathleen felt that she could ask questions when needed, and did not feel stressed when she was unable to remember something that others thought she should.

Ellen (friend living with dementia), provided a specific example of how being open was beneficial, as it allowed her to ask for reminders when needed.

But sometimes like if you’re having an episode or something and you’re having dinner with someone and you look at your knife and fork and you’re not sure what to do, that’s kind of embarrassing. You’re looking there, “I know I’m supposed to do something with them.” And then it’ll come back…Somebody will ask you what’s wrong. I’ll just say it ‘cause I’m not embarrassed and I’ll say, “I can’t remember what to do with that.” And they’ll say, “Oh you do this and this.” If Margaret’s there, she’ll laugh at me (laughs). But that’s okay.

Open communication about the diagnosis and being able to ask for help created a safe and comfortable space for friends to be themselves while getting the support that they needed.

Stepping in to provide support

Being open and honest about memory loss enabled participants to identify several practical ways of adapting to memory changes. Friends adapted to memory changes by providing reminders, accommodating memory changes, keeping an eye out for their friend with dementia, and being persistent.

Providing reminders and acommodating memory changes was a strategy used by friends to find ways to continue to spend time together. For example, Gloria reminded her friend about an activity they were doing together:

She has Chicken Soup for the Soul books. And so yesterday, she came for a visit. She was bored after supper and she started talking about that again. And I said, “Well, we have started already, Faye. The first time you read three short stories to me, and the second time you read three more short stories.” She couldn’t remember that, but she thought it was a good idea to continue.

Similarly, Carol (friend) told us how she came to realize that the reason her friend was not responding to invitations was not that she did not want to engage, but that she needed additional reminders.

I know that Patty will do things, not because she wants to sometimes, but because she feels I need it or I want her to do it with me. So I didn’t want to cross that line. I don’t want to be, “Come on. You’ve got to do this with me.” And then I realized she didn’t always remember. So … I don’t wait for her. I don’t say to her, “Call me if you want to do this.” I say, “Do you want to do this? Put it in your calendar.” And I’m probably more directive that way.

Carol would normally avoid pressuring her friend, Patty, to spend time together in case the activity was not of interest; however, she soon recognized that it was not a lack of interest but a change in memory.

In addition to providing reminders and accommodating memory gaps, friends kept an eye out for their friend with dementia, and stepped in when needed. Carol told us how she looks out for Patty, particularly in social situations.

…but if sometimes she’s across the room from me…and somebody will say…something, and I can see the look on her face is, “I don’t remember that. I don’t know what we’re doing next”, then I try to jump in to clarify, not making a point of clarifying it, like to say, “Oh, Patty, here it is”, but try to give her a hint. Or she’ll come over to me and say, “I don’t know what’s going on here.”

Patty’s approach involved taking care not to embarrass her friend, yet supporting her as needed. Keeping an eye out also involved ensuring the physical safety of the friend with dementia. Ben (spouse), spoke about how a group of friends looked out for his wife: “As an example, two weeks ago…we made a Friday trip and back Saturday [with friends]. Anyway, every one of us made sure Kelly didn’t disappear around the corner and not know where she was going…”. Friends were careful to look out for both the physical and emotional safety of the person with dementia by keeping watch and by stepping in to provide support or redirect their friend. They aimed to do so without causing embarrassment or eroding the friend’s autonomy by keeping an eye out, and by only stepping in when needed.

Being persistent

The final practical strategy involved being persistent. To maintain the friendship, a committed approach was needed. John (friend), who had developed a friendship after moving into long-term care, continued to spend time with his friend even after memory changes occurred.

I was told that she lost her memory and I said, “That’s too bad.” But I’d see her, I’d still talk to her and say, “Well, let’s go down [to a common area].” And you know, like sometimes she’d say, “Well, you go ahead.” And I’d say, “We can go down. There’s music down there.”

Although staff at the facility indicated that his friend was having difficulties with her memory that could impact their friendship, John demonstrated persistence by continuing to invite his friend spend time with him.

Allan (spouse), emphasized the importance of being persistent, particularly as Marilyn had cut many friendship ties following her diagnosis, believing that she did not want to be a burden on her friends as dementia progressed. In their interview, Marilyn provided advice for friends who wanted to keep in touch after a diagnosis of dementia.

[Friends should] go to the door. Go knock on the door….say, “Marilyn, let’s have a coffee. Let’s do something. What’s wrong with you?” And you get in the door. As long as you get your foot in the door, you’ve made it.

Marilyn regretted cutting ties with her friends and suggested that had her friends been more persistent when she turned away from them, she may have been able to sustain those friendships. These practical strategies served to help friends adjust to the changes associated with dementia.

Discussion

Through our data analysis, we generated several themes and subthemes that describe how people living with dementia and their friends adapted to the changes brought forth by a diagnosis of dementia. Changes in memory and behaviour can have a negative effect on relationships after a diagnosis of dementia (Harris, Reference Harris2011, Reference Harris2013). Despite these changes, social relationships remain important and there is a continued desire for relationships with friends (MacRae, Reference MacRae2011). The findings presented here support previous research (Harris, Reference Harris2011, Reference Harris2013; Perion & Steiner, Reference Perion and Steiner2017) by demonstrating that friendships can and do continue following a diagnosis of dementia. As the extant literature suggests, these friendships are characterized by loyalty, acceptance, and reciprocity (Harris, Reference Harris2013; Perion & Steiner, Reference Perion and Steiner2017). However, they also extend previous research by providing a more detailed account of specific strategies that dyads and groups adopt to sustain their friendship.

Our participants sustained their friendships by prioritizing the relationship, shifting their ways of thinking about their friend and their relationship, and adopting practical strategies to address memory changes. By using these strategies, participants created supportive spaces within their relationships to both honour and continue their commitment to the friendship. Further, drawing on these strategies allowed friends in particular to acknowledge that despite changes in memory and behaviour, their friend was a person who had thoughts, feelings, and strengths. We found that some family members supported these strategies by encouraging parents or spouses to be patient with their friends and provided suggestions for continued engagement by suggesting ways that friends could communicate or relate to one another. As such, family members may play an important role in sustaining friendship.

Participants prioritized their friendships by spending time together and connecting with each other in meaningful ways. Shared interests are a hallmark of strong friendships and for our participants, prioritizing personal contact may have provided a foundation for shifting ways of thinking about the friendship and adopting practical strategies. Acknowledging that the friend with dementia may need additional support but is still the same person may have facilitated friends’ willingness and effort to adjust their behaviour to better meet the needs of the individual with dementia as well as the needs of the friendship as a whole. Similarly to participants in MacRae’s (Reference MacRae2011) study, participants with dementia in the current study wished to be treated the same as they were before the diagnosis, and friends adopted strategies that both recognized and allowed for adaptation to changes while respecting the friend and that friend’s preferences. Although we were unable to follow friend pairs/groups over time, our findings suggest that the use of strategies to maintain the friendship, particularly on the part of the friend without dementia, may increase as dementia progresses. In particular, friends of those who were living in long-term care learned to draw on long-term memories, and practiced patience and kindness in their interactions.

Similar to previous research (Perion & Steiner, Reference Perion and Steiner2017), our findings emphasize the importance of reciprocity as a tool for sustaining friendships after a diagnosis of dementia. Both friends acknowledged that friendships continued to be reciprocal in nature, even when roles shifted within the relationships. Friends without dementia continued to rely on their friend with dementia for ongoing emotional and instrumental support. Both giving and receiving help from one’s friend was important for friends both with and without dementia (Perion & Steiner, Reference Perion and Steiner2017).

Our participants’ willingness and ongoing effort to maintain their friendships suggests that participants did not adopt the “tragedy discourse of dementia” (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Dupuis and Kontos2013, p. 2). Instead, the strategies presented here suggest that people living with dementia and their friends may resist common stereotypes associated with dementia rather than internalizing such negative stereotypes. Stigma impacted participants’ lives as others made assumptions about the abilities of their friends with dementia or lacked respect and kindness in their interactions. Furthermore, there was some indication that stigma had been internalized, as one participant was afraid to tell their friends about their diagnosis. However, friends may have buffered against stigma not only by accepting each other as they were, but also by looking out for one another, stepping in when needed to avoid situations that might be perceived as embarrassing or unsafe. Gentle prompts and reminders were used with kindness to avoid additional stigmatization. Several participants reminded themselves that their friend was the same person even after dementia led to changes in behaviour and memory, accepting friends as they are now, Sustaining friendships after diagnosis may be one means of counteracting this tragedy discourse and challenging stigma as these friendships focus on strengths, reciprocity, and mutual benefit. Use of these strategies among friends may counteract both imposed and self-stigma, thus reducing feelings of loneliness and isolation among people with dementia and leading to improvements in quality of life.

Theoretical Implications

This study was guided by SST (Carstensen, Reference Carstensen and Jacobs1993, Reference Carstensen1995) as well as the relational citizenship model (Kontos et al., Reference Kontos, Miller and Kontos2017). In keeping with SST, our findings highlight the emotional benefits obtained from connecting with a small number of close friends. When faced with a potentially life-shortening illness, participants re-committed to their friendships by adopting these strategies to sustain their relationships. Lansford et al. (Reference Lansford, Sherman and Antonucci1998) note that with age, people seek out emotional benefits from their relationships rather than seeking new knowledge. Participants found comfort and security in their friendships, along with opportunities to experience pleasure and joy with a small number of particularly supportive people.

Furthermore, friends engaged in relational citizenship as they used these strategies to sustain their friendships. Participants respected each other’s preferences and supported autonomy and interdependence as well as acknowledging the reciprocity experienced through these meaningful relationships. Social citizenship upholds opportunities for active engagement in life and opportunities to grow within dementia contexts (Bartlett & O’Connor, Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010). Friends sought out and supported engagement in life through their commitment to their relationships, and supported opportunities for growth. Indeed, the relational citizenship model could be expanded to acknowledge the importance of friendships that uphold embodied selfhood along with the values of active participation, and opportunities for engagement in life and growth.

Practical Implications

Our findings lend themselves to practical suggestions for both formal and informal services and supports. First, formal service providers (e.g., support groups, dementia education programs) could include discussion of the value of maintaining friendship within dementia as well as discussion of strategies used to maintain these friendships. Second, formal service providers could provide opportunities for friends to come together in a safe space to converse about their desires and needs related to the friendship. Third, opportunities to bring friends together through community-based leisure programs may provide additional space for prioritizing friendship and enabling friends to focus on each other rather than dementia. Long-term care facilities also have a role to play in facilitating opportunities to sustain friendships. In particular, friends can be included in formal and informal leisure opportunities within long-term care. Furthermore, reminders of the friendship, such as photos and other mementos could be incorporated into the room decor in long-term care. Long-term care staff may benefit from drawing on friends’ knowledge of residents to better understand their history as well as their strengths, values, needs, and desires.

Although data for this study were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, our findings have implications for long-term care during and after the pandemic restrictions that limit opportunities for social engagement for older adults living in long-term care. Use of technology after a move to long-term care, along with facilitated, in-person visits when it is safe to do so, may provide a means for friends to connect. Long-term care staff and administration could consider prioritizing friendships along with family relationships in order to increase opportunities for social support and engagement and reduce isolation and loneliness.

Limitations and Future Directions

Challenges with participant recruitment led to some limitations within our sample. In particular, we aimed to include people with dementia who were living in the community, in assisted living, and in long-term care to gain a broader picture of friendship in dementia and to include people at all stages of dementia in our research. Additional participants who were residing in an assisted living facility and long-term care may have added different perspectives and experiences to our findings. For example, they may have highlighted additional challenges and opportunities for maintaining friendships that occur after a move from community to institutional care. Also, although the inclusion of family members provided additional insight into strategies for maintaining friendships after a diagnosis of dementia, their perspectives on and experiences with friendship may differ from those of persons living with dementia and their friends.

Although the findings of this study shed light on how friendships can be sustained following a diagnosis of dementia, further research is needed. Longitudinal research that follows friendship dyads and groups over time could provide greater insight into how the process of maintaining friendship shifts as dementia progresses, particularly as persons with dementia move into long-term care. Additional research into the types of friendships (e.g., work-related friendships, friendships based on shared leisure interests) may indicate whether some types of relationships are more likely to weather changes than others, and may suggest that some types of friends adopt different strategies for adapting to change.

Conclusion

Friendships in which one friend has been diagnosed with dementia can be sustained by adopting a variety of strategies that uphold the dignity of the individual with dementia through acceptance, acknowledgement of strengths, and practical and emotional strategies aimed at adapting to changes. These friendships may provide much-needed social support after diagnosis. Further, they offer the opportunity to move away from negative stereotypes and the tragedy discourse too often associated with a diagnosis of dementia.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada (SSHRC) and the grant number was 430-2016-00516.