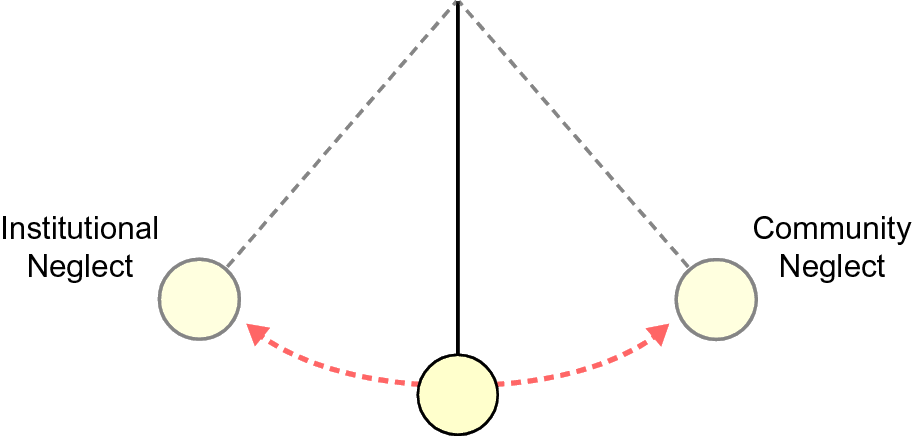

The history of serious mental illness (SMI) is grim, from a cultural as well as a treatment perspective. The conditions of individuals with psychotic disorders have swung, like a pendulum, from institutional neglect to community neglect and back again over the past several hundred years.Reference Dvoskin, Knoll and Silva 1 –Reference Doughty, Warburton and Stahl 4 At the core of treatment failure is a failure in mental health policy and funding, with the result usually framed as the degree of human institutionalization in jails, prisons, and asylums.Reference Penrose 5 –Reference Lamb and Weinberger 7 In the middle of the 19th century, institutions designed to deliver moral treatment were considered the humane answer to care properly for the SMI population. By the mid-20th century, those same, now overcrowded, institutions were blamed for the horrible conditions of mistreatment of individuals with SMI. Now, as we approach the middle of the 21st century, deinstitutionalization (the answer to the cruel asylums) is purportedly at fault for homelessness, lack of treatment, and criminalization. As the pendulum swings, we are hearing cries to “bring back” the asylums.Reference Sisti, Segal and Emanuel 8

Care providers currently working in the trenches delivering public mental health services to people with SMI know that society has failed to care adequately for this group. Individuals living with mental illness are now often living on the open streets or incarcerated, and on average die 20 years sooner than the rest of us.Reference Fazel and Seewald 9 –Reference Colton and Manderscheid 12 An examination of the history of the approach to people with SMI across time and geography indicates that we are just one data point on a cyclical pattern of treatment and policy failure through time.Reference Dvoskin, Knoll and Silva 1 –Reference Doughty, Warburton and Stahl 4

Figure 1 is an oversimplification, but illustrates the issue if you consider the current state of homelessness, criminalization, forensic institutionalization, and incarceration of people living with SMI in the wake of deinstitutionalization. The criminalization crisis is currently reaching the tipping point where it will begin to drive changes in policy. And so, we are at risk of watching the familiar pendulum swing in the same pattern: lock them up, let them out, lock them up. When a society fails to take care of humans with SMI in either setting, the pendulum will continue to swing between these two extremes. The social choices have historically been to either neglect them in state hospitals and prisons or to let them fall apart in the community (until such time as they are incarcerated or dead).

FIGURE 1. The pendulum.

FIGURE 2. History of mental health policy.

It is a fact, and we must accept it, that 1% to 2% of the population will develop a SMI. A significant fraction of that population will require high levels of publicly funded care, including medications, housing, and programs to find meaning through human contact. This care will be expensive, and it will be long-term. But it is cheaper than the alternatives.Reference Delgado, Breth, Warburton and Stahl 13

As leaders in the field of mental health, how do we make provision of that care a priority? In other words, how do we prevent the policy pendulum from continuing to swing between extremes of neglect within institutions and neglect outside of institutions? The institutionalization debate thus far has been whether we should lock up human beings with brain disease. Perhaps we need to broaden our understanding of what institutionalization means (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Are We Institutionalizing the Wrong Things?

The term institutionalization has more than one definition (https://www.lexico.com/definition/institutionalization). In addition to (a) the state of being placed or kept in a residential institution, the word also refers to (b) the act of establishing a new norm in a society. 14 Using the second definition, let us consider what has been institutionalized by human society vis-à-vis the approach to individuals with psychotic disorders. Medical treatment and psychological interventions have been routinely institutionalized. Whether it be insulin shock therapy, psychoanalysis, lobotomies, or indiscriminate polypharmacy, the mental health field has taken vague conceptual models for approaching this complex and poorly understood condition and institutionalized them to a point where they lack adequate flexibility. To that end, clinical certitude about these treatments is also cyclically institutionalized, only to be later exposed as hubris.

From a social perspective, funding sources, and a lack thereof, have also been institutionalized. Examples include the prohibition against federal reimbursement for inpatient psychiatric treatment, the enduring lack of mental health parity, and the fractured funding streams from local, state and federal resources, none of which fully address the full continuum of needs required by to care for psychotic illnesses. The very process of policy making has also been institutionalized into an incoherent cacophony of diametrically opposed stakeholders forcing their ideology and certitude into the process, rather than a nuanced approach to balancing paternalism and autonomy, or medicine and recovery, in a way that works in the best interest of this population. The result has been extremes such as unrealistic thresholds for involuntary treatment, the exclusion of individuals with criminal justice involvement from community resources, inadequate prioritization of psychotic disorders by systems at all levels, the overvaluation of privacy over family involvement and the subsequent unchecked explosion in forensic commitments, and incarceration as a result of all of these factors. 15 –Reference Powers 17

And most important, even though this illness impacts 1% to 2% of the population and virtually everyone knows someone who has fallen victim to a psychotic illness, human society has institutionalized a lack or responsibility for, moral judgment for, and a lack of compassion for people whose brains develop in such a way that they misperceive stimuli and reality. The deinstitutionalization debate needs to include a discussion of letting go of these rigid societal approaches to the 77 million people currently living in the world with SMI. We need to search for ways to institutionalize an ethic of responsibility and compassion for this 1% of our population who, in addition to losing their individual sense of reality as a function of disease, also lose their humanity and dignity as a function of social approaches to the treatment of this disease.

Is it possible to institutionalize compassion? Is it possible to institutionalize clinical flexibility, where mental health clinicians are open to the idea that biopsychosocial interventions of all types (including stable housing) are needed? Is it possible to institutionalize a practice of data collection and analysis, so that if systems are failing (eg, a 74% increase in forensic patients in state hospitals) it does not take decades to identify and respond?Reference Wik, Hollen and Fisher 18 Can we focus on real outcomes, such as lack of engagement with treatment, homelessness, incarceration, arrest and death; outcomes we know are pervasive?

Can we institutionalize humility? Psychotic syndromes are complex and poorly understood, and no one really knows from one patient to the next what caused or what will improve the symptoms. Yes, we have seen promising advances in neurobiology and psychopharmacology in the last few decades, but this knowledge is useless if the field of medicine fails to recognize our limitations without proper psychosocial support, and if society fails to deliver balanced treatment due to a lack of coherent mental health funding and policy.

But mostly, as a profession and moreover a society, can we institutionalize a sense of responsibility to care for these patients, who are our parents, children, neighbors and friends? Psychotic disorders are not going away, increasing forensic mental health budgets are not going away, the homelessness issue is not going away, just because we are ignoring it. The knowledge that SMI is characterized by a departure from reality, combined with a lack of insight, means that these individuals need our help. The good news is that there are things that work. With compassion, a sense of responsibility and a coherent approach, individuals living with SMI can live meaningful lives, for less money than the current state of criminalization.

Once we institutionalize an ethic of compassion and responsibility for the least fortunate members of our society, we will be able to manifest the obvious, logical, economical, and evidence-based continuum of care necessary to balance the pendulum. Once we recognize the limitations of rigid clinical ideology and polarized policy making, we can create an adequate, balanced, and properly funded system of care. This will prevent fractured mental health systems from continuing to collapse under the weight of the need.

The vision for a continuum is simple: it must address all stages of this relapsing and remitting illness, in the same way that medical care is delivered for other chronic conditions. This is achieved with adequate supplies of acute community hospital beds, crisis services, assertive community treatment, housing, vocational support, peer support, early intervention, therapy, socialization, case management, informed psychopharmacology, and a few straightforward metrics to monitor the need and maintain effectiveness. In other words, a modern health delivery system that focuses on prevention, takes responsibility for all patients, and has adequate resources when there is a crisis or exacerbation. We have the science and the collective intelligence, we just need the will. As the reader takes in the following material on decriminalizing mental illness, we encourage you to widen the lens beyond this moment in time and consider a new approach to the deinstitutionalization debate. Let us make room in our medical, psychological, advocacy, and academic environments to talk about changing the ethics of our approach to this disease. Let us also have this conversation in our dining rooms, courtrooms, churches, treatment spaces, and board rooms. We can stop the pendulum, for the first time in history, by creating a responsible and sustained approach to caring for SMI.

Disclosures

Stephen M. Stahl, M.D., PhD, Dsc (Hon.) is an Adjunct Professor of Psychiatry at the University of California San Diego, Honorary Visiting Senior Fellow at the University of Cambridge, UK and Director of Psychopharmacology for California Department of State Hospitals. Over the past 36 months (January 2016 - December 2018) Dr. Stahl has served as a consultant to Acadia, Adamas, Alkermes, Allergan, Arbor Pharmaceutcials, AstraZeneca, Avanir, Axovant, Axsome, Biogen, Biomarin, Biopharma, Celgene, Concert, ClearView, DepoMed, Dey, EnVivo, EMD Serono, Ferring, Forest, Forum, Genomind, Innovative Science Solutions, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Jazz, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, Neos, Novartis, Noveida, Orexigen, Otsuka, PamLabs, Perrigo, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Reviva, Servier, Shire, Sprout, Sunovion, Taisho, Takeda, Taliaz, Teva, Tonix, Trius, Vanda, Vertex and Viforpharma; he has been a board member of RCT Logic and Genomind; he has served on speakers bureaus for Acadia, Astra Zeneca, Dey Pharma, EnVivo, Eli Lilly, Forum, Genentech, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Otsuka, PamLabs, Pfizer Israel, Servier, Sunovion and Takeda and he has received research and/or grant support from Acadia, Alkermes, AssureX, Astra Zeneca, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Avanir, Axovant, Biogen, Braeburn Pharmaceuticals, BristolMyer Squibb, Celgene, CeNeRx, Cephalon, Dey, Eli Lilly, EnVivo, Forest, Forum, GenOmind, Glaxo Smith Kline, Intra-Cellular Therapies, ISSWSH, Janssen, JayMac, Jazz, Lundbeck, Merck, Mylan, Neurocrine, Neuronetics, Novartis, Otsuka, PamLabs, Pfizer, Reviva, Roche, Sepracor, Servier, Shire, Sprout, Sunovion, TMS NeuroHealth Centers, Takeda, Teva, Tonix, Vanda, Valeant and Wyeth.

Katherine Warburton does not declare any conflicts of interest.