I would only say that the more sociological history becomes, and the more historical sociology becomes, the better for both.

Edward Hallett Carr

Charles Tilly (1929–2008) was one of the greatest sociologists of the second half of the twentieth century. His incredible energy and creativity were a powerful force in reviving the historical-comparative perspective in social sciences and produced many new insights. Tilly has covered a very broad range of subjects, from contentious behaviour, urbanization, proletarianization, and state formation, to migration, democratization, and persistent social inequality. His oeuvre is so vast – he wrote or edited dozens of books and published hundreds of scholarly articles and countless book reviews – that it has become a challenge to synthesize. In the following article I will try to offer a comprehensive critique, in the hope that this will further interest in and debate about the subject. First, I sketch Tilly’s intellectual development since the late 1950s. Next, I discuss a few recurring themes from his work that are of special interest to historians of the working classes. I conclude with a critical review of Tilly’s achievements.

Tilly’s intellectual development, 1958–2008

Tilly’s academic career started with a remarkable volte face. In 1958 he obtained his Ph.D. degree at Harvard University for his thesis on “The Social Background of the Rebellion of 1793 in Southern Anjou”. His supervisors were the sociologists George C. Homans and Barrington Moore, Jr, who, like Tilly’s previous mentor and “great teacher” Pitirim Sorokin,Footnote 1 both advocated a historicizing perspective.Footnote 2 While editing his Ph.D. thesis for publication, Tilly had increasing misgivings about the simple, unilinear development idea from his previous project. He later wrote:

In that imperfect doctoral dissertation, I had leaned heavily on conventional ideas about modernization. The great counterrevolution of 1793 seemed to show the typical reaction of a backward, unchanging, agrarian society to the unexpected intrusion of modern political ways. As I said so, however, I began to doubt both the generalization and its application to the Vendée. It is not well established that “backward” regions react to political change in reactionary ways.Footnote 3

The published edition of his Ph.D. thesis did not appear until six years later and refuted his earlier theses. In this work, Tilly tried to provide a contextualized explanation for the course of events. Entitled The Vendée, the book marks the actual start of Tilly’s oeuvre as we know it, systematically comparing two adjacent parts of France, of which one (the Val-Saumurois) supported the French Revolution and the other (the Mauges) the counter-revolution. In an effort to explain the differences, he seeks a process (urbanization, in this case) that is sufficiently general to encompass broader patterns and does justice to the specificity of individual cases.

After completing his Ph.D. thesis, Tilly initially pursued two paths. First, he evolved into a contemporary urbanist. While employed at MIT and at Harvard’s Joint Center for Urban Studies he published on racial segregation, housing projects, and related subjects.Footnote 4 The peak and crowning glory of this research activity was the anthology, An Urban World (1974), which certainly was not wanting in historical perspective. From the mid-1970s, Tilly abandoned this intellectual course.

His historical studies were far more characteristic of his intellectual development. He remained very interested in French social history after completing his Ph.D. thesis and spent many years studying the course of social change and contentious behaviour in that country in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, dealing extensively with quantitative aspects. From around 1963, he worked with Edward Shorter and a few assistants (Lynn Lees, David Hunt) to construct a database, which served as the foundation for his widely publicized monograph Strikes in France, 1830–1968 (1974). Deeply influenced by the events of May–June 1968, this book revolved around a version of the modernization theory. The authors base their approach, for example, on Alain Touraine’s forms of organization of production (artisanal, mass production, science-sector production). Unlike Touraine, however, they associated these with “historical periods” that coincide with “phases of technological change” and “phases of collective action”.Footnote 5

Tilly remained interested in working on a team that gathered large quantities of information to study contention.Footnote 6 In the 1970s and 1980s three new databases were constructed under his aegis: (1) for France as whole, highlighting Anjou, Burgundy, Flanders, the Île de France, and Languedoc, since 1600; (2) for London and its surroundings from 1758 to 1820; and (3) for Great Britain (England, Wales, Scotland) as a whole from 1828 to 1834.Footnote 7 The French material ultimately gave rise to the publication The Contentious French in 1986. The British project was completed only in 1995, culminating in the publication of Popular Contention in Great Britain, 1758–1834.Footnote 8

Still, Tilly never became a pure cliometrician. He remained interested in the qualitative aspects of historiography – albeit from a social-science perspective.Footnote 9 This approach dominated his work from the mid-1980s onward. Tilly’s vast knowledge of French – and later also of British – social history paved the way toward his more in-depth analyses. For a long time he was interested primarily – but never exclusively – in Europe. The first clear sign of this interest was the anthology The Formation of National States in Western Europe (1975); followed by Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1990 (1990), European Revolutions, 1492–1992 (1993), and Contention and Democracy in Europe, 1650–2000 (2004).

From the 1990s, Tilly progressively abandoned his geographic approach and started to address “general” topics not associated with a specific country or region. He also deviated somewhat from his usual empirical style,Footnote 10 while seeming to shift his focus to the present and the very recent past at the same time. Together with his son, the economist Chris Tilly, he wrote Work Under Capitalism (1998). With Doug McAdam and Sidney Tarrow he published Dynamics of Contention (2001); with Tarrow – but without McAdam – Contentious Politics (2007); and as single author Contentious Performances (2008). He also took on general sociological issues, such as in Why? (2006) and in Credit and Blame (2008). The main emphasis of his research, however, was the question of which circumstances were conducive to stable parliamentary democracies. Tilly believed that three very different factors promoted democracy, namely broader access to political participation; improved access to political resources, and opportunities for different social groups; as well as curtailing autonomous or arbitrary coercive power within the state and outside. At first he studied these factors separately – in Durable Inequality (1998), The Politics of Collective Violence (2003), Trust and Rule (2005), and Regimes and Repertoires (2006) – and subsequently combined them in Democracy (2007), which was intended as a synthesis.

The wealth of books and articles that Tilly published since the late 1950s turns out to comprise a few “maelstroms” that were pivotal in all his work. He kept revisiting these central themes, trying out an idea, reformulating that idea, and so on and so forth, until a text emerged that was more or less “finished”. Once such a text was ready, Tilly generally left the topic concerned as it was – although in some cases he might reconsider it from a different perspective. This has led to a spiral-shaped course that causes many partial overlaps between publications, making some of his oeuvre seem somewhat repetitive.

Because a complete reconstruction of Tilly’s intellectual development would span far too many pages, I will merely review the “final products” in various fields here, although I will indicate briefly the predecessors to this final product in cases where a major learning process took place. I will address only Tilly’s historicizing writings.

Theory and methodology

Tilly was an exemplary scholar, who nearly always accounted for his theoretical and empirical steps. His work reflects a few methodological constants. First, he approached history from the perspective of a social scientist, which meant, in Tilly’s own words, that: “the historian as social scientist aims self-consciously at methodological rigor. He defines his terms, states his hypothesis, clarifies his assumptions (in so far as he himself is aware of them), and stipulates the criteria of proof”.Footnote 11 Second, it followed from this approach that Tilly never hesitated to correct himself publicly, if he found that definitions, typologies, or hypotheses needed to be revised. On this subject, he wrote in one of his most recent books: “Repeatedly I have thought I had identified an important principle, proved a crucial point, or found a superior way of communicating an argument only to discover that the principle suffered exceptions, the proof failed to convince, or the new rhetoric caused misunderstandings I had not anticipated.”Footnote 12 Third, Tilly made extensive use of the comparative method, which is “the systematic, standardized analysis of similar social processes or phenomena (for example, slavery) in different settings in order to develop and test general ideas of how those processes or phenomena work”.Footnote 13

In the past this social-scientific approach baffled historians. A writer for the Times Literary Supplement once observed about Tilly′s first book, The Vendée:

Dr. Tilly, armed with a battery of compasses, field glasses, range-finders, altimeters, so loaded down with apparatus that his prose limps heavily from one demonstration to the next, eventually ends up more or less where other, less prudent, more haphazard travellers have preceded him, after crashing impetuously through the bush, or simply following their eyes and noses. With Dr. Tilly, we go the long way round; the author will not even let us start off at all before he has offered us long disquisitions on “urbanization” in Kansas City, and minute definitions of such difficult words as “city,” “neighborhood,” “commune,” “affiliation,” “parish.”Footnote 14

The substance of Tilly’s work has consistently been historical-materialist, not in the sense of orthodox Marxism (much of his writing in fact reads like a critique of Marxism), but along the lines of an approach that targets the logic of material interests. Understandably, therefore, since his earliest publications, Tilly adopted a constructive-critical stand reflecting Marx’s ideology. In retrospect, he regarded himself as part of the 1950s “Marxist-populist drive” that aimed to promote history from below.Footnote 15 In 1978 he described his view as “doggedly anti-Durkheimian, resolutely pro-Marxian, but sometimes indulgent to Weber and sometimes reliant on Mill”.Footnote 16 In 1983 he argued that “if you want to observe the coalescence of historical perception with theoretical penetration, you can do no better than the work of Karl Marx”.Footnote 17 Even around the turn of the century, he still believed that Marxism could be innovated by discarding the reductionism of the 1960s and by pursuing the course charted by E.P. Thompson.Footnote 18 The main difference between Tilly’s approach and the traditional Marxist one is that Tilly places far greater emphasis on state formation, thereby attributing much more importance to political processes that do not derive directly from class conflicts. In this respect he adheres more to the tradition of Toqueville.Footnote 19

For a long time Tilly was a “hardcore” materialist who assumed a “structural realism” and focused on “objective” (i.e. economic, military, quantitative) aspects of social history. Only in the course of the 1980s did he become more aware of the subjective angle of social processes and did he start to transform his structural realism into a “relational realism” integrating structural and cultural elements. In an interview in 1998 he explained: “One of my major intellectual projects of the last decade or so has been to build a more adequate account of identity, agency, and culture.”Footnote 20

While thinking about these issues, he elaborated an approach that was vaguely discernible in his earlier work. On the one hand, Tilly objected early on to the structural functionalism of Talcott Parsons and others, which had been the dominant movement in American sociology until well into the 1960s. Tilly saw no merit in this approach or in similar “Durkheimian theories”, because they “build on a conception of a vague social unit called a society”, and consequently not only hide “the effective human actors” but depersonalize the historical process as well.Footnote 21 After the rational-choice model had gained influence in the 1980s, Tilly resisted that as well, arguing that human behaviour always includes an “erratic” aspect and is therefore impossible to interpret according to a methodological-individualist approach.Footnote 22

Tilly refused to use society or individuals as such as a unit of analysis. Instead, in keeping with the network theoretician Harrison White, he opted for the social relations between social sites – individuals, as well as households, neighbourhoods, and organizations. In a relational analysis, social inequality, for example, is examined not as the difference between two otherwise unrelated social positions but as a feature of the relationship between these positions. Accordingly, a boundary between the social sites needs to be defined for every social interaction. Who are “we”, and who are “they”? Such boundary construction is an ongoing process from which shifting identities keep emerging.Footnote 23

For a long time Tilly was a proponent of modernization theory, albeit frequently with reservations. In 1972, for example, he wrote that the modernization concept was “too big and slippery for deft manipulation”,Footnote 24 while arguing at the same time that the designation comprised multiple, partially contradictory processes. The modernization idea led to a unilinear image of history, in which stages succeeded one another, basically out of “necessity”. In 1990 Tilly criticized his The Formation of National States in Western Europe from 1975 as

[…] a new unilinear story […] running from war to extraction and repression to state formation […]. We continued, more or less unthinkingly, to assume that European states followed one main path, the one marked by Britain, France, and Brandenburg-Prussia, and that the experiences of other states constituted attenuated or failed versions of the same processes. That was wrong.Footnote 25

The transition from a modernization approach to a non-unilinear approach ultimately led to a focus on mechanisms, which in combination produce various outcomes. Very early on, Tilly objected to what he described as “Unnatural History”:

[…] a case in point is a recurrent article in the American Journal of Sociology, published with insignificant variations in title, authorship and vocabulary, which asserts by means of a handful of examples that there is a single underlying Process of Revolution. At first it looks like natural history, in the sense that it portrays the standard setting and life cycle of a distinct species of event. Closer inspection usually shows that the unnatural historian has begged the question by assuming that his identification of common sequences within the events singled out ipso facto confirms that they belong to the same species … as if declaring that a man’s life has a beginning, a middle and an end, then that a paper before a learned society has a beginning, a middle and (thank goodness) an end established that men’s lives and papers before learned societies came from the same species.Footnote 26

Over time, Tilly countered such a covering-law approach increasingly with a “mechanismic” approach, such as the one theoretically devised since the late 1980s by Jon Elster, Arthur Stinchcombe, and others.Footnote 27 His objective was to break complex historical sequences down into events or episodes, such as social movements, revolutions, or democratic transitions, and subsequently to investigate which “robust mechanisms of relatively general scope” figured in the course of these episodes. This meant that history no longer needed to be perceived as the outcome of “general historical patterns” but could be interpreted as a chain of contingent mechanisms.Footnote 28

State-building and capitalist development

Virtually from the outset, Tilly dealt with general trends in European history since the Middle Ages. Although he refined his analysis considerably over time, he consistently assumed that two master processes had a decisive influence, whether directly or indirectly: capital accumulation and state-building. Neither process was linear. Both included crises, reversals, and digressions. Neither one carried more historical weight than the other; they were autonomous developments that continuously exerted a reciprocal influence. Wars were endemic in the European system of states;Footnote 29 rulers relied increasingly on capitalists to finance the organization of violence, while capitalists needed states as guarantors of private property.

Into the eighteenth century, European states were either very small units, such as port cities with their hinterlands, or they were composed of highly autonomous segments. As a result, into the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries, rulers depended on compliance from regional power holders to collect taxes, recruit troops, and the like, and populations of states were extremely heterogeneous in a linguistic, cultural, and legal sense.Footnote 30 Tilly described this type of state structure as indirect rule:

Indirect rule included a wide range of social arrangements: the tribute-taking relation of the sultan’s court to local headmen in the Ottoman Empire, the holding of judicial, economic, and military power by great landlords in Poland, reliance on a faithful clergy in Sweden, concession of an enormous role in parish and county administration to English gentry and clergy justices of the peace, and survival of the Dutch Republic as a federation of fiercely competitive municipalities and their dependencies.Footnote 31

These states expanded gradually in size, while dwindling in number. In around 1500 Europe had about 500 autonomous political entities, averaging about 3,800 square miles (6,115 km2) in size, with an average population of 124,000. Four centuries later, 30 states remained, averaging 63,000 square miles (101,389 km2) in size, with an average population of 7.7 million.Footnote 32 Although dynastic politics and the formation of federations were in part responsible for this concentration, wars were, in Tilly’s view, the driving force behind the state-building process for a long time, as these “provided the chief occasions on which states expanded, consolidated, and created new forms of political organization”.Footnote 33 The coercive core of the emerging states enabled them to deactivate all competing organizations.Footnote 34 The extent to which war-making influenced the state structure depended on the interaction between the type of war concerned, the nature of the economic relationships, and the fiscal strategy. To achieve larger concentrations of capital and coercive means, various paths could be taken. A somewhat simplified version of these paths would be: (a) the coercion-rich and capital-poor path of e.g. Poland and Russia; (b) the coercion-poor and capital-rich path of e.g. the Netherlands; and (c) a “middle path” where coercion and capital were about equally significant, such as in France and Britain.Footnote 35

In the period 1750–1850 the internal structure of the European states changed drastically. Segmentation made way for consolidation. Rulers gained direct control of large, heterogeneous areas. They built reinforcements along the borders and disarmed individual citizens and rival power-holders, in part by dismantling castles, disbanding private armies, controlling arms production, prohibiting duels, and confiscating weapons. Parallel to this effort, they set up a proactive police force dedicated to preventing unlawful acts, including unlawful collective action, in part through patrolling and surveillance, rather than punishing criminals ostentatiously and publicly after the fact. In addition, rulers imposed uniform military, legislative, judicial, fiscal, monetary, and cultural systems on their populations. No longer did they stay in touch with their subjects via authoritarian, privileged intermediaries. Instead, they intervened directly in their daily lives.Footnote 36 The result was a shift from indirect to direct rule. Around 1850,

States had substituted their own officials for the patrons of old, tax farming and similar practices had almost vanished, elected legislatures connected the more substantial citizens to the national government, and census-takers brought royal inquiries to individual households, as national bureaucracies attempted to monitor and regulate whole countries and all their residents.Footnote 37

Once again, war-making was the main cause of the changes. As the size and power of states grew, wars became increasingly costly and destructive. The armies of mercenaries that had dominated European warfare from the fifteenth until the seventeenth centuries became too expensive and were replaced by domestically recruited standing armies of conscripts and volunteers, while the burden of taxation was raised simultaneously. This trend and the resulting resistance led complementary organizations to be set up (treasuries, tax offices, conscription mechanisms) and to perform interventions directly palpable in the local communities. To be accepted by the population, states had to make concessions and grant ordinary people rewards and rights to which they had not been entitled in the past.

The consolidation of states thus coincided with a dual process of circumscription and central control. Circumscription means that states greatly tightened their control over the resources on their territory: movements of capital, goods, people, and ideas started to be regulated. Central control means that states devised a system of instruments for central information processing and surveillance (censuses, bureaus of statistics, inspectorates, police forces) and started to interfere in infrastructure, working conditions, education, agriculture methods, and many other matters. Circumscription and central control had a clear cultural connotation, in that they were conducive to a measure of cultural homogenization within the state borders. Whereas in non-consolidated segmented states, such as the Hapsburg Empire, all different religions and languages were acknowledged by the state forces, consolidating states promoted the establishment of an official national language and a standardized interpretation of the national past via schools, monuments, museums, and other media. The emerging nationalism appeared in two manifestations. Wherever the state construed a specific ethnic group as “state-supporting,” the resulting state-led nationalism aimed to have all residents of the state adopt specific cultural forms. And wherever this new nationalism denied or suppressed the identity of some groups, state-seeking nationalism might materialize, embodying the desire of some set of people to acquire their own state, where they celebrate their own distinctive, national culture. State-led nationalism thus stimulates state-seeking nationalism. Consolidation of states coincided with the creation of new, collective identities and redefinition, legitimation, or in fact de-legitimation, of old, collective identities – a process that did not actually give rise to fully homogeneous states anywhere.Footnote 38

Tilly devoted considerably less attention to the capital-formation process than to the state-building one. He was deeply influenced by the proto-industrialization studies of the 1970s by Franklin Mendel and others.Footnote 39 Tilly argued that the European economy had also evolved in two stages. During the first stage, from 1500 to 1800, accumulation had occurred decentrally. Merchant capital was mobile and more likely to shift to locations where labour was available than vice versa. Economic growth was achieved via the multiplication of small, widely dispersed production units connected with one another by merchants via a putting-out system. The result was “a finely articulated hierarchy of markets from local to international, with local markets that corresponded to the geography of labor”.Footnote 40

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries accumulation patterns changed. Capital concentration grew and affected labour processes far more directly, as labour flocked increasingly to the locations of such capital. As a consequence, industrial production and services came to be concentrated in cities, while the countryside de-industrialized in many regions and specialized in agriculture and livestock breeding. What was known as the Industrial Revolution was merely an “illusion”, caused by the coincidence of an urban implosion and mechanization.Footnote 41

Urbanization, migration, and proletarianization

Like Lewis Mumford, Tilly regarded the city as the combined outcome of state-building and capital-formation.Footnote 42 In The Vendée he observed that urbanization was a prominent force. Urbanization is regarded there as the outcome of two developments, namely market expansion, requiring on the one hand, “communication, specialists in coordination, and penetration of existing, traditional forms of social organization”, and on the other hand, state centralization, which “encourages the rise of specialists in political coordination and manipulation, calls for more frequent exchanges of orders and information, draws formerly isolated regions and communities into greater contact with decision-making centers, and into greater dependence upon them”.Footnote 43 Urbanization, however, was not only a dependent variable but in turn promoted state-building and capital-formation as well. Especially in the period 1500–1800, good-sized cities relied on cash crops from the surrounding countryside. Commercial agriculture promoted the prosperity of merchants and small and medium-sized farmers, which in turn reduced the leverage of the great landlords, also with respect to the monarchs.Footnote 44

While the number of European states diminished since 1500, cities increased in both number and size. This divergence led the number of large cities in each state to grow considerably and caused a shift in fiscal strategies, demands for services, and political relationships. State bureaucracies expanded, land taxes became less significant, and – from the mid-eighteenth century onwards – forms of collective action and surveillance changed.Footnote 45 Urbanization was paralleled by changes in the nature of the countryside. The transition from subsistence polyculture to cultivation of cash crops for the urban market had major social ramifications:

The producer binds himself to distant and nameless consumers, adopts new standards for evaluating his work, requires for his yearly operation information from a much wider range of sources than before, and depends on market specialists both as sources of commodities he now needs and as a means for the sale of the cash crops he now produces.Footnote 46

By 1500–1800, geographic mobility was already substantial, with annual migration rates of 10 per cent and higher, although this migration was often local and took place between nearby villages or to a city in the surroundings. Such migration was also promoted by the natural demographic decline occurring in nearly all European cities during the early modern period: deaths outnumbered births. Even in demographically stagnating cities, demand for migrants from nearby villages and towns persisted. Only from the nineteenth century onward was this pattern replaced by two other movements, namely extra-continental migration (an estimated 50 million people, mostly proletarians, between 1800 and World War I) and short-distance commuting.Footnote 47

In his analyses of migration processes Tilly emphasized that the effective units tended to be sending and receiving social networks – in some cases related to one another – rather than individuals and households. After looking for answers to two questions, namely how long migrants left their sending area, and how definitive their rift with the sending network was, Tilly devised multiple typologies of migration patterns over the years. Three forms keep resurfacing in his publications: (1) in circular migration people return to their area of origin after a clearly circumscribed interval (seasonal work on harvests, etc.); (2) chain migration entails extended displacements with active support from related sending and receiving networks; and (3) in career migration persons or households move more or less permanently, because large structures (firms, governments, armies) offer them opportunities for upward social mobility. Other patterns identified by Tilly in some cases include colonizing migration (which entails integral transfer elsewhere of a segment of a sending network) and coerced migration, such as the slave trade, for example, in which all ties between migrants and sending network are severed. Some of these patterns overlap, and a few (e.g. career migration) are numerically less significant than others.Footnote 48

Proletarianization is, according to Tilly’s description, “the declining control of households over their own means of production, and the increasing dependence of those households on the sale of their labor power”.Footnote 49 Proletarianization is caused by capital-formation and indirectly by state-building as well. The two causes of this process were: (1) states protected the capital, because it benefited them financially and thus promoted auspicious accumulation; and (2) state-building coincided with rising taxation that forced the population to engage in market transactions, as this was the only way they could earn money to fulfil their obligation toward the state.Footnote 50

Proletarianization in Europe took place in two stages. In the first stage (until roughly 1800) the majority of the proletariat was in the countryside. Because of de-central capital-formation and the concurrent cottage industry in rural areas, plus the impoverishment of parts of the agrarian population, even in Britain, the heartland of the so-called Industrial Revolution, relatively more proletarians lived in the countryside than in the cities for a long time. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when capital became concentrated in the cities, and the countryside de-industrialized, the relative share of rural proletarians declined, and city workers became concentrated in larger production units.Footnote 51

In an audacious attempt to quantify the pace of this proletarianization in Europe, Tilly generalized the data that Karlheinz Blaschke had found for the Kingdom of Saxony to apply to the entire continent (not including Turkey and Russia).Footnote 52 His estimate is shown in Table 1 above.Footnote 53

Table 1 Population growth and proletarianization in Europe, 1500–1900 (in millions)

A population’s growth or decline is always the combined result of three mutually dependent factors: natural increase (births minus deaths), social mobility (accessions to the population minus exits from the population), and net migration (immigration minus emigration). Tilly argued that in Europe natural increase (children of proletarians become proletarians as well) was the most important factor explaining proletarianization, especially after 1800. While the limited capital of their households forced artisans and peasants to marry fairly late and to limit family size, proletarians married early and had a high fertility rate: the more “hands”, the higher their income.Footnote 54 Tilly proposed the following hypothesis:

[…] on the average, proletarians responded to economic expansion with greater declines in mortality and greater increases in fertility than nonproletarians did and responded to economic contraction with greater increases in mortality but no greater declines in fertility than nonproletarians did. The consequence was a disproportionate natural increase of proletarians in good times, not completely compensated by the natural decrease of bad times.Footnote 55

Relying on some “strong guesses”, Tilly provided very rough estimates of demographic growth rates (Table 2 above).Footnote 56

Table 2 Some components of European demographic growth (annual percentage rates of increase)

Tilly’s hypothesis clearly differs from the view often defended – which we have already observed in Marx’s work and elsewhere – that the most important component of the proletariat’s growth was mobility from non-proletarian to proletarian positions. This hypothesis has been subject to considerable criticism.Footnote 57

In a few publications, among which the most important is Work Under Capitalism, and which Tilly wrote together with his son Chris, he attempted to understand the labour relationships of wage earners. Contrary to neoclassical economists alleging that market forces and technology determine the nature of work, he advocated a far broader approach that took into account social context and connections. Focusing on “work contracts” – which he interpreted as “the prescribed relations” between workers and other parties involved in their work – Tilly devised a model for labour relations under capitalism that accommodated historical and cultural variations, emphasizing the three main types of work incentives: coercion (threats to inflict harm), compensation (wages, tips, bonuses, etc.), and commitment (invocation of solidarity).Footnote 58

Collective claim-making

Both state-building and capital-formation entail fundamental conflicts that generate open contention. State-building coincided with three types of conflicts: (1) growing states drew heavily on the resources of their subject populations (conscription, taxation), which led to resistance; (2) consolidating states competed with great lords for support from these same populations; and (3) groups within the domain of the states vied for resources, rewards, etc. under the state’s control. Capital-formation added three other types of conflicts: (4) the opposition of capital and labour, i.e. between the owners of the production means and those who worked for them; (5) the struggle between capitalists and others enforcing claims to land, labour, and other resources; and (6) competition among capitalists. These conflicts would lead several parts of the population to claim property, provisions, and freedom. The exact course of state-building and capital-formation largely determined timing, social foundation, form, and outcomes of such collective claims. “Massive peasant rebellions, for example, occurred chiefly in bulky, poorly capitalized, coercion-intensive states, while the struggles of guilds for power and privilege concentrated in the territories of intense commercial capitalism and capitalized states.”Footnote 59

Once collective claims are enforced by the public authorities (state agents) these claims turn into rights. Claims that are not enforced or are enforced by parties other than the public authorities (e.g. by hired squads of thugs) are therefore not rights.Footnote 60 To enforce claims, a state requires a certain governmental capacity, which means that governmental actions should be capable of affecting “distributions and deployments of people, activities, and resources within the government’s territory”.Footnote 61

Tilly took greater interest in conflicts arising from state-building than in those attributable to capital-formation; even in his studies about strike behaviour, he focuses on the political aspect.Footnote 62 His basic assumption was that within a population several groups tried to influence the government. On the one hand, there are the contenders, who routinely claim support from the government in the form of resources or actions; they pertain to the polity, i.e. the set of all successful contenders. On the other hand, there are the challengers, who even though they request support from the government like the contenders do not routinely receive it. Contenders are therefore insiders, while challengers are outsiders.

Contenders cannot expect to remain part of the polity automatically. Their success depends on their ability to mobilize a sufficiently large following or clientele, possibly through coercion tactics. If eventually their efforts cease to be effective, they are excluded from the polity. As the changes in composition of the polity accelerate, the contestations, which in some cases are more and in other cases less violent, will broaden. Conflicts occur especially between contenders, between contenders and challengers, and between challengers and agents of the state (police, army), and less frequently between challengers or between contenders and state agents. Sometimes such conflicts will cause a polity to break up into more than one. If such a condition continues for an extended period, it is a “revolt” or a “civil war”, which may lead to permanent division of a territory into two or more autonomous territories. Constituting a new single polity following a period of fragmentation means, according to Tilly, that a revolution has taken place.

The complex of claim-making, as well as the emergence, the logic, and the consequences thereof, are pivotal in Tilly’s oeuvre. The questions that probably preoccupied Tilly the most during his lifetime are: “Under what conditions will normally apathetic, frightened, or disorganized people explode into the streets, put down their tools, or mount the barricades? How do different actors and identities appear and transform in episodes of contention? Finally, what kind of trajectories do these processes follow?”Footnote 63

Tilly became convinced very early on that protest did not erupt out of the blue from discontent about rampant unemployment and high food prices. He objected vehemently to what he called “the Hydraulic Model”, which holds that protest ensues almost automatically when people fall on hard times: “hardship increases, pressure builds up, the vessel bursts. The angry individual acts as a reservoir of resentment, a conduit of tension, a boiler of fury”.Footnote 64 In response, Tilly tried to discover rationality in collective action. One of his basic principles was that the nature of contentious politics changes as the most important addressee (the state) changes character, while at the same time the state changes because of contentious politics as well. Adequately conceptualizing this correlation proved particularly difficult. During the first few decades Tilly remained captivated by the modernization idea and invested enormous intellectual energy trying to relativize this mindset. In the 1960s and 1970s – tempted by the work of Eric Hobsbawm and George RudéFootnote 65 – he successively used several schemata based on three evolutionist stages. First, he identified “primitive”, “reactionary”, and “modern” collective violence. He believed that these stages paralleled centralization of state power: first, local, small-scale forms of protest dominated; as the power of the state increased, resistance focused on preserving established rights; finally, there was the resistance that accepted the existence of centralized states and pursued expansion of rights.Footnote 66 A few years afterwards, he introduced another trio denoting the claims of the protest, distinguishing “competitive”, “proactive”, and “reactive” action.Footnote 67

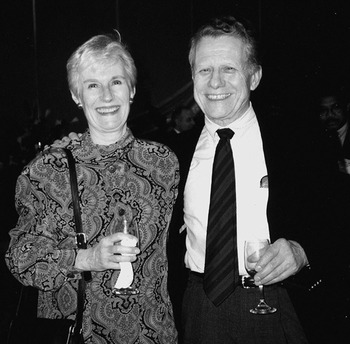

Figure 1 Charles Tilly and Louise Audino Tilly at the 1994 American Historical Association in San Francisco after Louise had delivered her presidential address. Louise Tilly became widely respected for her historical studies on collective action, women, and family life. Together from the 1950s till the mid-1990s, the Tillys were not only a couple, but also a scholarly team, teaching together and pursuing a number of joint research projects. Photograph by Marie Kennedy. Reprinted with permission.

In the second half of the 1970s, however, Tilly realized that these schematas should be discarded. In retrospect, he observed:

[…] a form such as the strike sometimes appeared in all three contexts; the categories actually described claims, not forms, of action. What is more, the trio’s teleological tone bothered me, especially when other authors adopted it as an evolutionary scheme. It sounded suspiciously like modernization theory. The comparisons that my collaborators and I had undertaken in The Rebellious Century (1975), in the work on Great Britain I had recently begun, and in the research on France I was starting to synthesize made the weaknesses of the tripartite scheme apparent.Footnote 68

Dissatisfaction with the classification led Tilly – as it previously had Erving Goffmann – to resort to theatrical metaphors. After all, claimants resemble actors: they have a limited repertoire (petitions, demonstrations, etc.), which they perform whenever they wish to present their claims collectively to the authorities or to opponents. So there are always certain repertoires of contention comprising several performances each. Repertoires may therefore be described as “the limited, familiar, historically created arrays of claim-making performances that under most circumstances greatly circumscribe the means by which people engage in contentious politics”.Footnote 69 Performances and repertoires are never expressed solely by the claimants but consistently evolve into a confrontation with the adversary, the object of the claims. They involve continuous interaction between the authorities and the claimants. Assemblies are prohibited, consultation occurs, demands are presented, borders are explored: in this respect the repertoire is always the outcome of bargaining. It is plastic and changes over time.

In one of his final books, Contentious Performances (2008), Tilly elaborates on this idea, convincingly arguing here that public collective contention “overwhelmingly” involves “strong repertoires”, which means in part that:

– In particular times and places, performances cluster into a limited number of recurrent, well-defined types.

– Within the range defined by all contentious actions that a given set of actors carry on, substantial blanks appear; combinations of actions clearly lying within the technical reach of participants never occur. As a result, performance types have visible boundaries rather than distributing continuously over the space of technically possible performances.

– For a given set of actors and issues, those performances change relatively little from one round of action to the next; what happens in one round of action, furthermore, detectibly constrains what happens in the next round. […]

– New performances arise chiefly through innovation within existing performances, but tend to crystallize, stabilize, and acquire visible boundaries once they exist.Footnote 70

A great many factors influence the development of performances and repertoires, such as “the population’s daily routines and internal organization (example: the grain seizure depends on the existence of periodic public markets and on a population that relies on those markets for survival)”; “prevailing standards of rights and justice (example: the firm-by-firm strike depends on the presumption that people have the right to dispose of their own labor)”; “the population’s accumulated experience with collective action (example: the appearance of the demonstration of a standard form of contention depends on the discovery that some sorts of officials are more likely than others to listen to demands that have the visible backing of large numbers of determined people)”; and “current patterns of repression (example: the adoption of the public meeting as a vehicle for protest depends on the vigor with which the authorities have been breaking up public meetings)”.Footnote 71

Tilly used his databases to hypothesize that the transition from indirect to direct rule (1750–1850) coincided with a significant shift in the repertoire of contention. Until about 1800 the performances were parochial, particular, and bifurcated – “mostly local in scope, adopting forms and symbols peculiar to the relationship between claimants and the objects of their claims, either acting directly on a local relationship or asking privileged intermediaries to convey claims to more distant authorities”. Such parochial actions included land invasions, rough music, seizures of grain, or expulsions of tax collectors. From the nineteenth century onward, the repertoire gradually became cosmopolitan, autonomous, and modular:

[…] cosmopolitan because both the scope of action and the objects of claims commonly spanned multiple localities; autonomous because the organizers of such performances frequently scheduled and located them in advance at their own initiative rather than taking advantage of authorized assemblies or routine confluences of people; modular because they employed very similar performances across a wide range of issues, groups, localities, and objects of claims.

Examples include public meetings, demonstrations, firm-by-firm strikes, or electoral rallies.Footnote 72

Both types of repertoires were effective in the context where they were used; labelling one backward and the other modern is therefore inappropriate. While the old repertoire comprised ephemeral actions, those in the new repertoire tended to be components of longer-term projects. The new repertoire marked the rise of national social movements.Footnote 73

Tilly long avoided the concept of “social movements” – I suspect that he adopted the notion only in the 1980s.Footnote 74 And only at the start of the twenty-first century did he perfect his own definition of the term. Tilly believed that a social movement was a synthesis of three elements. The first was a finite campaign that connected three parties with one another: the claimants, the object or objects of the claimants, and the general public. The second consisted of the WUNC displays, meaning that the participants aimed to achieve Worthiness, Unity, Numbers, and Commitment: they were well-dressed and were accompanied by dignitaries, clergy, or mothers with children; they demonstrated their unity through banners, singing, and chanting slogans; they were as numerous as possible; and they showed their dedication by braving adverse weather, resisting repression, and the like. The third was the contentious repertoire, as described above.Footnote 75

According to Tilly, social movements originated in Britain during the first half of the nineteenth century, as a result of wars, parliamentarization, capitalization, and proletarianization. Wars, as we observed above, gave the government greater control over the daily lives of the lower classes and led state agents to try to convince large parts of the population to support the war effort financially or in person. Increasing influence from parliaments – the outcome of war efforts financed partially through measures subject to parliamentary approval – made clear to large sections of the population that these bodies of elected representatives were important for their existence. The growing significance of agrarian, commercial, and industrial capital reduced the independent influence of large landowners. And proletarianization reduced the direct dependence of the lower classes on certain landlords, masters, and other patrons. Together, the four elements gave rise to coalitions between different social groups and caused proletarian and petit-bourgeois activists to stop allowing the “short-term effectiveness” of collective action to prevail and to think instead in terms of the “long-term cumulation of efforts”.Footnote 76

As a consequence of increasingly successful civic claim-making, the share of non-military state expenditures in the budget grew during the nineteenth century. Parallel to this process, capitalists and workers alike managed to embed rights and privileges in the state. “Establishing the right to strike, for example, not only defined a number of previously common worker actions (such as attacks on nonstrikers and scabs) as illegal, but also made the state the prime adjudicator of that right.”Footnote 77

One aspect of political contention that always interested Tilly was collective violence, i.e. “social interaction that immediately inflicts physical damage on persons and/or objects [….], involves at least two perpetrators of damage, and results at least in part from coordination among persons who perform the damaging acts”.Footnote 78 He published on this subject over the course of more than four decades. Tilly consistently argued that violence was a “normal”– albeit not an intrinsically desirable or inevitable – aspect of contention: “violent protests tend to accompany, complement, and extend organized, peaceful attempts by the same people to accomplish their objectives”.Footnote 79 After discarding the modernization idea, Tilly devised a classification of forms of collective violence ranging from violent rituals and coordinated destruction, via brawls to so-called “opportunistic” acts, such as kidnapping, hostage-taking, gang rapes, etc.Footnote 80

One far-reaching form of contentious politics that ordinarily coincides with collective violence is revolution. Tilly’s revolution concept corresponds with Leon Trotsky’s notion of “dual power”,Footnote 81 although it differs significantly from it as well. Trotsky assumed that two opposing classes were vying for state control. Tilly believed, however, that this model contained unnecessary restrictions. There could be more than two blocks, and these blocks need not consist of only one class but might be based on class coalitions. This less rigid approach is necessary to label the French, Mexican, and Chinese revolutions as such.Footnote 82 Revolutionary situations arise when contenders or coalitions of contenders try to seize control of the state or of part of the state and have the support of a significant share of the population, while the rulers are unable or unwilling to repress or give in to these contenders.Footnote 83

Citizenship and democratization

From the 1990s onward, Tilly returned to the key theme of his mentor Barrington Moore, Jr and investigated the circumstances under which states democratize or de-democratize. At this point he definitively broadened his geographic horizon and examined state formation in all parts of the world, emphasizing contemporary affairs far more than he had done previously. Tilly’s earlier studies on French and British history had made clear to him that contentious politics changed the form of states. In Popular Contention in Great Britain, Tilly had demonstrated that struggles between popular groups and ruling elites had led to “parliamentarization” of the national state and had given rise to the national social movement. This change also brought about a new connection between local and national levels – namely citizenship. In one of his last works Tilly defined citizenship as “mutual rights and obligations directly binding governmental agents to whole categories of persons defined by their relationship to the government in question”. Citizenship therefore exists only if “governmental capacity is relatively extensive, rights extend to some significant share of a government’s subject population, some equality of access to government exists among political participants, consultation of political participants makes a difference to governmental performance, and political participants enjoy some protection from arbitrary action”.Footnote 84

Citizenship is a necessary but not an adequate condition for parliamentary democracy. In a programmatic text from 1995, entitled “Democracy is a Lake”, Tilly observed that the rise of citizenship made democracy “an option” but not “a necessity”.Footnote 85 After all, modern dictatorships such as National Socialism and Stalinism provided for fairly broad and equal citizenship. Democracy is a specific form of citizenship that provides citizens with considerable protection from arbitrary acts by the state and involves mutually binding consultation: state agents fulfil the wishes of the population, and the population observes the corresponding rules drafted by the state agents. A regime therefore becomes more democratic, when: (1) a larger share of the population, (2) is consulted on a more equal basis, and (3) is more protected from the state’s arbitrary action, while (4) the state agents and the population pay more attention to one another. As the state increases its “capacity”, it becomes better able to promote democracy. A regime can therefore be democratic only once the state can enforce its decisions.Footnote 86 Of course high capacity does not guarantee that a state will be democratic; high capacity is obviously compatible with a dictatorship as well.

The question that truly preoccupied Tilly was which circumstances promoted, or in fact obstructed, democratization. He understood that social movements as such did not inevitably result in democracy; after all, they could also pursue social inequality and exclusion, as did racist movements.Footnote 87 Conversely, democracies might come about without social movements, as became clear, following the Allied occupations of Germany and Japan in 1945.Footnote 88 In the course of his quest for an answer, Tilly ultimately realized that formulating sufficient conditions for democratization and de-democratization was impossible, although processes that promoted or obstructed democratization were identifiable.

Three types of changes promoted democratization in Tilly’s view. First, existing trust networks (trading diasporas, kinship groups, religious communities, etc.) should not remain aloof from the state but should integrate significantly into the regime to get their members to engage in mutually binding consultation. Second, categorical inequality – distribution of the population into different groups with collectively diverging life opportunities, depending on social class, gender, race, caste, ethnicity, religion, or nationality – is not translated directly into categorical differences in political rights and obligations: severe social inequality will not intrinsically impede democracy, provided that citizens have basically the same political rights. And third, autonomous power clusters, especially those with concentrated coercive means need to be placed under the aegis of public politics and become part of regular citizen–state interactions.Footnote 89

– Trust networks Footnote 90 are not intrinsically conducive to democratization; in numerous cases they have in fact obstructed democracy.Footnote 91 What matters is that trust networks are integrated in the state, either directly (e.g. via social security systems) or indirectly (e.g. via trade unions, churches).

– Tilly interpreted categorical inequality as comprising dual inequalities, such as those between black and white, male and female, citizen and non-citizen, etc. Such inequalities mean that one category has far less access than the opposite category to certain resources (e.g. coercive means, skills, animals, land, machines, financial capital, information, media, knowledge). Two mechanisms engender such inequalities, namely Marxian exploitation and Weberian opportunity-hoarding. Exploitation means that members of a categorically bounded network appropriate resources generated entirely or in part by others, for which these others are not compensated for the full value added. Opportunity hoarding occurs when members of a categorically bounded network monopolize a valuable resource that reinforces the network. Such inequalities become durable when transactions across a categorical boundary (e.g. black–white) regularly benefit one of both sides, and the boundary is reproduced.

Categorical inequality (in the sense of sustained differences in advantages by property ownership, religion, gender, or race, etc.) is not ordinarily created deliberately from the outset. It is more likely to come about as follows. First, people try to appropriate certain resources through exploitation or opportunity-hoarding. If they succeed, the resulting inequality needs to be consolidated; this requires distinguishing insiders from outsiders, monopolizing knowledge and power, and ensuring loyalty and succession. All this may be achieved by establishing categorical boundaries. Democracy only becomes possible, when categorical inequality becomes insulated from public politics: “Democracy can form and survive so long as public politics itself does not divide sharply at the boundaries of unequal categories. Conversely, political rights, obligations, and involvements that divide precisely at categorical boundaries threaten democracy and inhibit democratization.” Here lies an important reason for the “natural affinity” between democracy and advanced capitalism. The cause is not the “ideological compatibility of democracy and free enterprise”, but rather that fully fledged capitalist states do not require categorical inequality to exist. After all, it makes no material difference whether such states obtain their financing from a small group of capitalists or from a large group of taxpayers. Because economic growth has led to a situation where “citizens, workers, and consumers coincide”, democracy becomes a realistic option.Footnote 92

– Autonomous power clusters on the territory of a regime may operate within the state (e.g. army officers) or outside (e.g. war lords). Reducing their power increases the control of the state and facilitates popular influence in politics.Footnote 93

Figure 2 Schematic summary of Tilly’s view on European history, 1500–2000.

Critique

In addition to being exceptionally prolific, Charles Tilly supervised hundreds of Ph.D. theses and influenced a broad circle of researchers from Spain and the Netherlands to Japan and China, thanks to the many translated editions of his publications. Both sociologists and political scientists, as well as historians, find him inspiring. At the same time, Tilly’s approach has met with profound reservations, especially among historians. His studies are often considered encouraging, but in many cases also diagrammatic and overly simplistic.

These doubts are attributable in part to Tilly’s intellectual stand. As we saw, he was inclined to embrace a form of historical materialism, although at heart he was a radical-democratic pragmatist, somewhat similar to John Dewey. Tilly believed that politics was about defending and promoting civil rights.Footnote 94 Epistemologically, he cared mainly whether his intellectual constructs “worked”, meaning whether they did what they were supposed to do: “Theories are tool kits, varying in their range and effectiveness but proposing solutions to recurrent explanatory problems.”Footnote 95 The tool-kit vision leads to a certain philosophical superficiality, as well as to lenience with respect to concepts and hypotheses. If a classification or suspicion proves unfounded, it is no tragedy but does call for a better solution.

This pragmatism has significant shortcomings. This is already clear from the most primary “tools” that researchers use, namely their definitions. Over time, Tilly has provided many dozens of definitions of processes, institutions, and events, all attuned to the limited historical and geographical framework within which he wished to apply them. A definition that “works” in time frame T1 in region R1, however, may prove ineffective in a different time frame T2 or a different region R2 and may as a consequence complicate studying a change (T1 → T2), as well as comparison with a different region (R1 ↔ R2). His description of states as “coercion wielding entities”, for example, reduces the core tasks of public authorities to domestic repression and international warfare. In Europe this is most applicable for the early modern period, but it is less meaningful for later periods, when national states appeared “as schoolteachers, social workers, bus drivers, refuse collectors, and a host of other guises”.Footnote 96

Even within a certain context (T1, R1), Tilly was at times inclined to narrow his scope. When he discussed the economy, he was referring primarily to merchant and industrial capital, often, although not in all cases, neglecting the interests of large landowners, small farmers, etc. William McNeill noted that “agricultural differences are entirely absent from his [Tilly’s] purview”, even though “until very recently the great majority of Europeans lived on the land; and differences in the techniques of cultivation, property law, and harvest results probably had more to do with European state-building than commercial capital and cities did”.Footnote 97 This shortcoming appears to apply to much of Tilly’s oeuvre, although there are some exceptions.Footnote 98 Likewise, Tilly’s definition of capital as “any tangible mobile resources, and enforceable claims on such resources” is so broad that differences between contexts (T1, R1 ↔ T2, R2) become invisible.Footnote 99 Christopher Chase-Dunn and Thomas D. Hall have responded: “By this definition a Nuer headman’s cows are capital.” Tilly seems to confuse accumulation as such with capitalist accumulation: “The storing of yams by a Trobriand chief is not capitalist accumulation. Neither is the hoarding of treasure in temples or cathedrals.”Footnote 100 Due in part to this overly broad perception of capitalism, Tilly is unable to acknowledge a transition from pre-capitalist relationships to a capitalist world system, rendering his reconstruction of European developments fundamentally biased: “Rather than positing a major transformation of the mode of production (a concept which Tilly does not employ) during the period he is studying, Tilly maps out the different paths by which European states increased their powers over domestic groups.”Footnote 101

Based on his definitions, Tilly aimed to perform a “neat” analysis of “untidy” processes.Footnote 102 In the complex and chaotic reality, he tried to identify essential causal patterns that perhaps did not explain this whole reality but did account for a characteristic feature of it. Accordingly, he reduced a major share of European history since 1500 to two processes (capital-formation and state-building), which he tried to use to explain as many other phenomena as possible. To my knowledge, not even Tilly’s harshest critics ever disputed that Tilly achieved a lot this way. He presented several insights and hypotheses that advanced historical research, including some about the relationship between state-building and claim-making, changing repertoires of contention, and the causes of democratization and de-democratization.

The method therefore has merit.Footnote 103 Note, however, that Tilly did not apply it equitably in all cases. He paid far more attention to state-building than to capital-formation. As a result, important aspects of the trends reviewed received insufficient consideration in his analyses. French historian Heinz-Gerhard Haupt observed, for example, that the fixation on the state monopoly on violence and disregard for the class differentiation that coincided with the rise of capitalism is an obstacle to understanding “that neither village-level conflicts nor opposition to state fiscal policy dominated in the Ancien Régime. Instead, parallel to consolidating the absolute monarchy, violent clashes that pitched farmers against bourgeois or aristocratic landowners over the use of the commons prevailed.” The consequences of capitalist accumulation for class relationships “fade”, and the structural violence embedded in economic relationships is overlooked, i.e. the violence contained in socio-economic relationships that produces “cumulatively disadvantageous inequality, which penetrates public awareness depending on the state of the economy and is contested in class conflicts”.Footnote 104

The second problem with Tilly’s dual-process model is the structuralist interpretation of capital-formation, state-building, and derivative developments. Even though Tilly may have intended otherwise, contingency hardly figures in his analyses. Despite his relational approach moreover, he ordinarily appears to view individual operators or social groups, merely as character masks – puppets that simply will not come to life.Footnote 105 This somewhat mechanistic approach leaves courses of events devoid of dialectics. Barbara Laslett’s observations about Durable Inequality hold true for many of his other writings as well: “There are no contradictions for Tilly, no dynamics of change that are internal to his model or vary by the specific historical conditions that one is attempting to analyze.” As a consequence, “the actor – the human agent – is lost from sight”. And because the actors are lacking, “consciousness and intention is, at most, incidental and ephemeral in his model”.Footnote 106 This “structural overstretch” is clear from Tilly’s use of the mechanism concept since the 1990s. On this subject Dilip Simeon has rightly remarked that: “the use of mechanical metaphors is apposite, as long as we remember that they are metaphors”. But, “no social-scientific machinery, however sophisticated, can provide a satisfactory explanatory account for such historical events as the role of Gandhi in the communal politics that unfolded in Calcutta during 1946–1948 or that of Lenin in revolutionary Russia between April and October 1917”.Footnote 107

A deterministic and unilinear historical perspective is a factor here. William Sewell has observed that in Tilly’s view human intervention may at best delay historically inevitable processes but cannot stop them.

Thus for Tilly, even the most spectacular outbursts of collective violence such as those that took place during the [French] Revolutions of 1789 and 1848 do not actually change the course of history. Collective action is merely an effect or a symptom of deeper causes. The course of history is determined by anonymous sociological processes operating behind or beneath the frenetic struggles and contentions that Tilly actually describes in his articles and books.Footnote 108

Such unilinearism will quickly lead to Eurocentrism. Even though Tilly regularly expressed interest in developments outside the North Atlantic region, he took historical experiences outside this area less seriously than he might have.Footnote 109 Based in part on Popular Contention in Great Britain, José Antonio Lucero remarked:

While Tilly is very far from being a vulgar modernization theorist, Great Britain comes close to seeming like the original crucible in which national states, social movements, and modern citizenship were forged. […] Such statements can not be proven until the histories of collective action in Latin America, Africa, and elsewhere are written. I do not suggest that “the social movement” actually originated in eighteenth century Peru or that the British experience is unimportant for other parts of the world. Rather, I urge only that […] we worry more about the particular histories of collective action in places like Peru and engage in more broadly comparative analysis on colonial and postcolonial states. Otherwise, the logic of “modular forms of collective action” crowds out alternative etiologies and histories.Footnote 110

Comparing experiences in the North Atlantic with those in other parts of the world suggests that the state-formation logic that Tilly postulated was based on presumptions not made explicit.Footnote 111

Over time, Tilly apparently felt a need to refine and expand his historical model,Footnote 112 especially when he started to introduce cultural aspects that he had overlooked in the past. In his first book, The Vendée, he discussed a rebellion, devoting less than one page to Catholicism, even though this religion was paramount.Footnote 113 One sign of the change in Tilly’s position was when he introduced the “contentious-repertoire” concept, presented commitment as a work incentive (in addition to compensation and coercion), and started to view trust networks as a precondition for democracy. Still, Tilly never expanded his model consistently to reflect this change. His entire macro-analysis continued to revolve around capital and coercion. Adding culture as a third macro-category at some point would have been logical, but Tilly never took this step.Footnote 114 Although we can only speculate about the reasons, complete integration of cultural elements would presumably have compelled Tilly to discard his structuralism as well and to transform his explanatory model in addition to expanding it. Anthony Smith, for example, has argued that had Tilly not neglected the ethnic aspect, his state formation theory would have appeared in an entirely different light; after all:

[…] if political leaders wish to create states and form nations under the appropriate social and technological conditions, they can only do so if the ethnic conditions are similarly favorable; and the more appropriate those ethnic conditions, the more likely are they to succeed in creating both states and nations.Footnote 115

Many aspects of Tilly’s oeuvre are undoubtedly subject to criticism. Nonetheless, Tilly’s “sociology of the long pull” has demonstrated how useful focusing on a few basic long-term processes can be:Footnote 116 concentrating on a select number of essential trends facilitates a better understanding of the complex reality. At the same time, the points of criticism reviewed above make clear that parts of Tilly’s model merit revision in the future, so that it may be embedded in a broader analysis that accounts not only for the North Atlantic region but for the world as a whole and consequently reflects greater consideration for capital-formation, culture, and the non-coercive aspects of state intervention. This will help us to reconstruct history as a “rich totality of many determinations and relations”.Footnote 117

Translation: Lee Mitzman