One of the most influential concepts in the field of Canadian politics and political science more generally is the left-right spectrum (for example, Budge et al., Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tanenbaum2001; Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015; Farneti, Reference Farneti2012; Freire, Reference Freire2008, Reference Freire2015; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart, Dalton, Flanagan and Beck1984; Jahn, Reference Jahn2010; Joshi and O'Dell, Reference Joshi and O'Dell2013; Klingemann et al., Reference Klingemann, Volkens, Bara, Budge and McDonald2006; Knutsen, Reference Knutsen1997; Lakoff, Reference Lakoff2006, Reference Lakoff2016; Laponce, Reference Laponce1981; Lipset et al., Reference Lipset, Lazarsfeld, Barton, Linz and Lindzey1954; Mair, Reference Mair, Dalton and Klingemann2007; Noël and Thérien, Reference Noël and Thérien2008; Sani and Sartori, Reference Sani, Sartori, Daalder and Mair1983; Steger, Reference Steger2009). What exactly constitutes left and right is, however, hotly debated and seemingly contingent upon time and place (Bobbio, Reference Bobbio1996; Jahn, Reference Jahn2010), with some perceiving the left-right divide as essentially “meaningless” while others believe it is “as universal and quintessentially human as blood pressure” (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015: 179).

In this article, I develop the argument that political scientists and the general public would stand to benefit by using the labels of right and left to describe preferences for the concentration or de-concentration of power across different issue domains. My aim here is to provide clarity and additional nuance to the commonly held view that the left-right spectrum is largely (a) unidimensional and (b) based on disagreements over equality, with the political left seeking greater equality than the political right (for example, Bobbio, Reference Bobbio1996; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1990; Jost et al., Reference Jost, Glaser, Kuglanski and Sulloway2003; Lipset et al., Reference Lipset, Lazarsfeld, Barton, Linz and Lindzey1954; Noël and Thérien, Reference Noël and Thérien2008). While agreeing with the first point regarding the spectrum's unidimensionality, I contend that the aspect of equality most at stake in what is commonly labelled left-right divergence concerns equality of power, which I define as differential preferences over whether power should be concentrated more narrowly among a smaller share of people (or entities) or de-concentrated/diffused more broadly to a larger share. Further, I argue in favour of distinguishing among different issue domains, given that political parties sometimes vary in their power-concentration preferences across domains (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015; Freire, Reference Freire2015). As discussed below, my “one dimension, multiple domains” theoretical framework offers three novel contributions to conceptualizing the left and right.

First, while equality is indisputably a core element of the left-right spectrum, the term equality is now championed by almost all political actors in some shape or form. This is in part because equality is inherently an ambiguous concept. Thus, I believe an analytical focus on power equality and contestation over the relative power of different members in a society allows us to get closer to the heart of global divides over the left-right spectrum.

Second, while I concur with the dominant view that the left-right spectrum is a manifestation of a single underlying dimension, given the inescapable complexity of politics, I argue in favour of distinguishing between those who seek to de-concentrate power and broaden inclusion (left) from those advocating for a concentration of power (right) in specific political domains. The reasoning here is because political actors do not always seek to consistently concentrate or diffuse power across different domains. To give an example from south of the border, American political parties may disagree on how to distribute economic power within their country while simultaneously preferring for their own country to exercise dominance in international economic relations as opposed to holding differing views regarding the de-concentration of economic power among countries. In other words, some may prefer power concentration in Domain A yet power de-concentration in Domain B. Conversely, some might believe that power de-concentration is generally desirable but that power concentration in Domain A is a necessary precondition for power de-concentration in Domain B and Domain C.

Third, I provide an empirical illustration of my “one dimension, multiple domains” framework by conducting a comparative analysis of eight contemporary political parties in Sweden, where political competition has long been structured along a left-to-right dimension (see, for example, Joshi and Navlakha Reference Joshi and Navlakha2010; Aylott Reference Aylott and Pierre2016; Oscarsson and Holmberg Reference Oscarsson, Holmberg and Pierre2016). My goal in this exercise is not to interpret survey respondents’ or party members’ associations regarding what they think is left and right—ideas that are heavily shaped by particular socialization experiences and exposure to political information (see, for example, Freire, Reference Freire2015; White, Reference White2011). Rather, my aim is to offer a new conceptualization and basis for analytical labelling of what is left and right that may help to promote greater awareness of the fact that a single underlying dimension of contention can still produce multiple left-right spectra across different domains. That is, a political party's location at one position (for example, to the left) on any single spectrum may also coincide with a contrasting placement (for example, being toward the right) on another spectrum that adheres to a different issue domain even if a party holds a default disposition toward power concentration, as most parties arguably do.

The rest of this article proceeds as follows: The next section reviews how the left-right spectrum has traditionally been conceptualized. I then re-interpret this literature to explain why power may actually be the core issue of left-right contestation. Next, I demonstrate my “one dimension, multiple domains” framework by conducting a comparative empirical analysis of eight political parties’ policy stances across three issue domains. Finally, I conclude with reflections on my observation that a single underlying dimension of contention (that is, concentration of power) can still manifest differently across varying political domains.

Literature Review

The idea of a left-right continuum is commonly used to distinguish between competing political parties, ideologies, value systems and policy approaches. In short, “the concept of left-right . . . has come to be regarded as an overall ideological dimension, as a kind of ‘super issue,’ as ideology” (Arian and Shamir, Reference Arian and Shamir1983: 139–40; see also Freire, Reference Freire2015; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart, Dalton, Flanagan and Beck1984; Knutsen, Reference Knutsen1997). While the terms left and right may strike some observers as empty signifiers whose meanings cannot be fixed (for example, Gauchet, Reference Gauchet and Nora2006), a common interpretation is that the left pursues egalitarianism whereas the right prefers hierarchy both within and among nations (Noël and Thérien, Reference Noël and Thérien2008: 31). As for its geographical scope, Freire and Kivistik (Reference Freire and Kivistik2013) found left-right divides to exist in all four continents they examined, although it was most prominent in Europe and North America.

The labels of left and right are Western in origin and have long been used to contrast competing perspectives between the left (secular, pro-poor) and right (religious, pro-rich) on the political cleavages of religion and class (Laponce, Reference Laponce1981; Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). With the terms widely used in Western public discourse, Gallagher et al. (Reference Gallagher, Laver and Mair1992) found it easy at the fin de siècle to align most European political parties along a left-to-right spectrum ranging from Communists, New Left, Socialists, Social Democrats, Greens, Agrarians, Left Liberals, Right Liberals, Christian Democrats (Protestant), Christian Democrats (Catholic) and Conservatives to the Extreme Right. Self-defined left/right (or liberal/conservative) political orientations have also been regularly elicited by analysts from political party manifestos and public opinion surveys. For example, the Comparative Manifestos Project finds “the left-right scale generally opposes emphases on peaceful internationalism, welfare and government intervention on the left, to emphases on strong defense, free enterprise and traditional morality on the right” (Budge et al., Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tanenbaum2001: 21). Surveys likewise find differences in attitudes toward privilege and disadvantage, such as a tendency for the right to blame the poor for being poor, whereas the left faults society and its elites for creating poverty. As one study put it, “Right activists attributed significantly more to self, i.e. habits and ability of the poor, and to fate of the poor as causes of poverty. . . . Left activists attributed significantly more to governmental policies and economic dominance of a few in the society as the causes of poverty” (Pandey et al., Reference Pandey, Sinha, Prakash and Tripathi1982: 330).

As scholars have documented, the historical consciousness of left-right politics dates back to the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when various political movements and parties began to name themselves as right or left, a trend that first emerged in France and Italy before spreading toward countries to the north (Laponce, Reference Laponce1981: 53–54). Over time, parties once considered on the left were also relocated toward the centre or right as more radical groups emerged to take up the leftist space (Mair, Reference Mair, Dalton and Klingemann2007). Eventually, the left-right distinction became regularly applied to conflicts between “labour-capital, communism-fascism, and progressive-conservative” (Fuchs and Klingemann, Reference Fuchs, Klingemann, Kent Jennings and van Deth1990: 206). This was especially the case during the twentieth-century Cold War, which pitted left against right on a global scale (Bobbio, Reference Bobbio1996; Noël and Thérien, Reference Noël and Thérien2008).

As Bobbio (Reference Bobbio1996: 16) notes, “the collapse of the Soviet system did not bring about the end of the left, but simply the end of a left-wing movement over a specific historic period,” and it is clearly evident in the twenty-first century that left-right terminology is widely used to distinguish political parties, attitudes and movements. For instance, scholars of globalization compare neoliberalism on the right with the global justice movement on the left (Steger, Reference Steger2009). Commentators likewise use these terms to distinguish contemporary populist movements, whereby “Right-wing populism endorses a nativist notion of belonging, linked to a chauvinist and racialized concept of ‘the people’ and ‘the nation’ . . . right-wing populism presents itself as serving the interests of an imagined homogeneous people inside a nation state, whereas [adherents of] left-wing populism . . . have an international stance, look outwards and emphasize diversity or even cosmopolitanism” (Wodak, Reference Wodak2015: 47).

In many Western democracies, scholars have similarly observed a close relationship between leftist parties and support for “democracy, the welfare state, peaceful internationalism, and labour,” whereas “capitalist economic orthodoxy remains a core idea of the right,” though it has been “joined over time by additional ideas such as patriotism, traditional morality, support for the military, and especially law and order” (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015: 123).

Given these findings of changes over time, some scholars have questioned whether left-right contestation might actually be multidimensional. For instance, Inglehart (Reference Inglehart, Dalton, Flanagan and Beck1984: 26) noted how socio-economic class-based left-right cleavages do not always overlap with an emerging “materialist-postmaterialist dimension.” Knutsen (Reference Knutsen1997: 194) similarly identified three sequentially unfolding cleavages of “religious/secular, left-right materialist and materialist/post-materialist, representing the central ‘pre-industrial,’ ‘industrial’ and ‘post-industrial’ value orientations” as a basis for parties’ and individuals’ left-right identification. By contrast, Sani and Sartori (Reference Sani, Sartori, Daalder and Mair1983: 330) crucially distinguished between a “domain of identification” and “space of competition” in politics. Building on this nuanced distinction, comparative empirical work by Freire (Reference Freire2015: 58) finds the left-right spectrum to indeed be “an encompassing ideological divide because it is anchored in multiple value orientations.” Thus, when it comes to identification, multiple issue domains are of interest to voters. However, in inter-party competition, parties are still essentially dispersed across a single left-right spectrum, which largely determines their potential coalition partners (Freire, Reference Freire2015).

Alternatively, Baradat (Reference Baradat2000: 15) has proposed that change is the core issue behind the left and right, labelling those preferring the most change (most left) as radicals (seeking revolutionary change); followed by liberals (seeking reform); moderates (seeking minor reforms); conservatives (preferring the status quo); and lastly reactionaries (seeking regression to an earlier state of affairs), who are furthest to the right. But scholars have also noted that objectivity is difficult to achieve in studying the politics of left and right because “people who belong to either side will tend to define their own side with words that are axiologically positive and the other side with words that are axiologically negative” (Bobbio, Reference Bobbio1996: 37). For example, the right uses words such as “tradition” instead of “conservatism” or “hierarchical order,” while the left uses terms such as “emancipation” (Bobbio, Reference Bobbio1996: 50). Moreover, a focus on change can frequently be reconciled with egalitarianism, as in the influential view of Lipset et al. (Reference Lipset, Lazarsfeld, Barton, Linz and Lindzey1954: 1135) that the left advocates “change in the direction of greater equality” and that the right supports “a traditional more or less hierarchical social order” while “opposing change toward greater equality.”

Another contention is that leftists and rightists might acquire their policy preferences from different sources. One hypothesis is that there is one right and multiple lefts, as proposed by Lakoff (Reference Lakoff2006: 94), who argues that “progressives tend to be divided by issues, modes of thought and attitude. They focus on their differences more than their similarities. Conservatives are much more effective in coming together. What unites them cognitively is strict father morality and their view of freedom.” Conversely, Cochrane (Reference Cochrane2010: 592) makes a compelling case that all leftists are motivated by equality, whereas there are both “pro-business” and “religious” rightists. Thus, there may be less coherence among various right-wing positions, suggesting that they derive from potentially competing sources, such as tradition, religion and incentives (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015: 41).

My focus on power in this article, however, may reveal underlying commonalities among seemingly disparate positions on the right or left that operate primarily at a subconscious level (see Jost et al., Reference Jost, Glaser, Kuglanski and Sulloway2003, Reference Jost, Federico and Napier2009, on how left-right ideology is largely subconscious). For example, what free-marketers and religionists on the right may have in common and what may enable them to form coalitions is the desire to concentrate economic purchasing power (in the hands of successful businessmen) and moral decision-making and agenda-setting power (in the hands of ordained clergy), whereas leftists object to such power concentration in the secular-religious and economic domains. Similarly, the right-wing person who favours aspects of free-market capitalism (such as international flows of products and investments) but opposes immigration (international flows of labour) may actually have a consistent preference for concentrating national power in the hands of current citizens (by excluding newcomers) and concentrating economic (spending) power in the hands of those able to earn profits by taking advantage of a labour-capital power asymmetry, whereby international capital mobility is deregulated (freedom for capital) but international labour mobility (especially from third world to first) is highly regulated and often prohibited (restrictions on labour). In other words, across issue domains as seemingly unrelated as religion, immigration and economic regulations, political party alignments may still largely stem from the same underlying dimension of contestation: whether power should be concentrated or diffused.

Theory

While supporting the prevailing consensus that the left-right spectrum is largely unidimensional, I contend that the underlying dimension of contestation is not just about equality but, above all, concerns the diffusion or concentration of power. Power, itself, is a contested concept but can be understood as famously defined by Max Weber (Reference Weber1947: 152) as “the probability that one actor in a social relationship will be in a position to impose his will despite resistance.” As Bachrach and Baratz (Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962: 948) have argued, “power is exercised when A participates in the making of decisions that affect B. But power is also exercised when A devotes his energies to creating or reinforcing social and political values and institutional practices that limit the scope of the political process to public consideration of only those issues which are comparatively innocuous to A.” As Lukes (Reference Lukes2005) asserts, a person or entity (such as a nation-state) can exercise power over others via the three dimensions of decision making, agenda setting and preference shaping, while Gaventa (Reference Gaventa2006) has identified how power is exercised in different spaces, varying from the highly restricted or exclusive (that is, closed or invitation only) to spaces that are more inclusive, claimed or created by participants themselves. Thus, power lies not only in its visible exercise but also in an entity's capabilities (see Lampton, Reference Lampton2008: 8–11).

Regardless of the arena or domain in which power is exercised, however, the relevant dimension is whether various powers (such as spending power, military capabilities, voting power, mass media control, agenda-setting power and so forth) remain concentrated in the hands of the few or the many. For example, should all states have nuclear weapons so they can defend themselves against an invasion (de-concentration of power) or should only great powers be able to protect themselves in this manner, thereby leaving states such as Canada correspondingly more vulnerable and less powerful? Should economic power be de-concentrated so that all states and individuals have roughly the same amount of purchasing power? Should all stakeholders have equal voting power or should voting power be reserved for those who are male adult citizens or belong to a specific ethnic or racial group? As these questions reveal, power is a core issue of political contestation. As I will now explain, there are multiple advantages to conceptualizing equality of power as the key dimension underpinning the left-right spectrum.

First, a focus on power helps us make sense out of supposedly shifting left-right dynamics over the last few centuries. In the past, major battles took place between those on the right wanting to concentrate moral authority and power in the religious establishment (the Church) and those on the left advocating a secular diffusion of moral authority to each individual (Laponce, Reference Laponce1981). Those seeking to concentrate voting power more narrowly among propertied men on the right stood against those on the left advocating universal male and female suffrage (Ishay, Reference Ishay2008; Noël and Thérien, Reference Noël and Thérien2008). Those seeking to concentrate economic power in the hands of (relatively few) industrialists on the right (capitalists) were likewise opposed by those seeking to diffuse power to the working classes on the left (socialists) (Bobbio, Reference Bobbio1996). Contestation has also broken out between pro-establishment forces on the right against anti-establishment forces on the left seeking to include people (or issues) traditionally left out of formal politics on account of their age/generation, gender, ethnicity/race, nationality, or species/the environment (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart, Dalton, Flanagan and Beck1984). But in all of these cases, though the issue domains of contestation changed over time, the single dimension of who should hold power remained the underlying issue of contention between left and right.

Second, a focus on power enables us to resolve what has previously been described as a liberty/egalitarianism tradeoff between right-wing and left-wing politics. These two objectives may at times be opposed, as Bobbio (Reference Bobbio1996: 74) has noted, citing the example of how “an egalitarian regime which obliged all its citizens to wear the same clothes would prevent each person from choosing his or her preferred clothes” Yet, as he goes on to explain, “loss of freedom naturally affects the rich more than the poor, whose freedom to choose a means of transport, a type of school or a way of dressing is normally restricted not by public decree, but by their economic situation within the private sphere” (75). Moreover, preferences for either authoritarianism or liberty have long been found among parties associated with both the left and right (Bobbio, Reference Bobbio1996: 79; Eysenck, Reference Eysenck1954: 110; Noël and Thérien, Reference Noël and Thérien2008: 25), and the supposition that liberty and egalitarianism are always in opposition is actually a false dichotomy because egalitarian measures do not always restrict freedom (Sen, Reference Sen1995). The deeper underlying issue at stake here appears to be power. As Bobbio himself observes: “The extension of voting rights to include women did not restrict the freedom to vote for men. It may have restricted their power in the sense that support for a government no longer depended only on them, but the right to vote was not restricted. Equally, recognition of personal rights for immigrants does not restrict citizens’ personal rights” (Reference Bobbio1996: 76; italics added).

As this passage illustrates, it is not just equality but, most importantly, the distribution and diffusion of power that is contested in domains such as who is entitled to vote and become a citizen. Similarly, at the international level, adding a permanent seat for Canada to the United Nations’ Security Council would not deprive current members of their seats, but it would still likely be contested by current seat-holders because it would dilute their concentration of power within the council.

Third, there is much evidence to suggest that those typically labelled as right-wing favour concentration of power in various domains. This may stem from pessimistic views of human nature, in general, or an admiration for the “elite” who are superior to common folk. For instance, extensive psychological research on system justification theory has found that adherents of right-wing ideologies perceive “existing social and economic inequalities as legitimate and desirable” (Jost, Reference Jost2019: 286). These studies also find that “conservative and right-wing orientations are generally associated with stereotyping, prejudice, intolerance, and hostility toward a wide variety of outgroups, especially low-status or stigmatized outgroups” (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Federico and Napier2009: 325). Such attitudes and behaviour imply that those with right-wing orientations seek to preserve the power concentration of the status quo. As conservatism correlates both with “in-group favoritism for members of high-status groups” and “outgroup favoritism for members of low-status groups” (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Federico and Napier2009: 325), it seems that “the disadvantaged might embrace right-wing ideologies under some circumstances to reduce fear, anxiety, dissonance, uncertainty, or instability whereas the advantaged might gravitate toward conservatism for reasons of self-interest or social dominance” (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Glaser, Kuglanski and Sulloway2003: 342). In other words, among those subscribing to right-wing ideologies, the advantaged presumably do so to keep power concentrated in their own group, while for other reasons (such as reducing cognitive dissonance), the disadvantaged also seek to keep power concentrated in the group that already has power.

In a claim compatible with system justification theory, Baradat (Reference Baradat2000: 25) argues that “conservatives see people as relatively base and even somewhat sinister. Hence, the conservative view tends to favour authoritarian controls over the individuals in society.” Analysts also find that right-wing parties “believe that the government should be a firm authority that expresses moral voice. To these parties, order is preferable to unbridled participation and freedom” (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002: 967). Relatedly, scholars have observed how economic policies championed by the right often aim to protect or facilitate power concentration by supporting higher-income business owners and managers through lower taxes, less regulation and privatization, while the left putatively tries to benefit lower-income labourers by means of state-owned enterprises, full employment and welfare state services funded by taxes on capital and profits (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002: 967). As Baradat (Reference Baradat2000: 40–41) argues, on the political right, “supply-side economics” calls for “money to be funnelled from the government directly to big business,” accompanied by an “increase [on] taxes on the poor and middle class while reducing government services to them through cuts in social programmes such as government aid to education, job training programmes, social security, and so on.”

Support for concentrating power on the right is likewise evident among right-wing populist movements that oppose sharing their national resources, welfare state services or citizenship privileges with outsiders. For instance, in the case of Sweden, the far-right Sweden Democrats political party has sought to stop asylum in Sweden and “enable more people to return to their home countries,” believing “Swedish welfare should prioritize Swedish citizens” and “foreign citizens who commit crimes in Sweden should be deported” (SWD, 2020a; see Appendix A for the source of this and subsequent political party quotes appearing in this article). Mirroring right-wing populists in many other countries, this party aims to concentrate domestic resources (and therefore power) more narrowly on those who already hold citizenship, while reducing opportunities for outsiders to acquire citizenship.

Fourth, there is much evidence to suggest that many of those typically labelled as left-wing favour a diffusion of power, though not always across all domains. For instance, during the twentieth century the left was split between social democrats seeking power diffusion in both the political and economic domains (favouring democracy and socialism) versus Soviet communists who sought only to diffuse power in the economic domain via concentrating power in the political domain (authoritarianism) (Steger, Reference Steger2008). By contrast, in the twenty-first century, leftist parties generally reject authoritarianism and more consistently support both political and economic power de-concentration, though with differing emphasis on domains such as gender, race, nationality and species (Freire, Reference Freire2016). For example, today progressives see foreign policy as ideally fulfilling the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Lakoff, Reference Lakoff2006: 90), a set of precepts that maintains that power over important dimensions of a person's life should be diffused to the individual level (as rights) rather than concentrated in the hands of political or economic elites. As Baradat (Reference Baradat2000: 34–35) observed, “Today's left tends towards internationalism and the right toward nationalism. Leftists speak of all people being brothers and sisters, arguing that national boundaries are artificial and unnecessary divisions [are] setting people against one another.” Leftist economic policies are also more inclined toward demand-side economics, which aims to “increase government regulation and taxation of big business” (Baradat, Reference Baradat2000: 41) while providing higher benefits to the poor and more aid to education, government job training and employment programs.

The pursuit of power de-concentration is also observable among newer left parties such as the Swedish Green Party (2020: 3), founded in 1981 “to be a voice for those who cannot make themselves heard.” The Swedish Greens seek to diffuse power not only across species and generations, via their guiding principles of “solidarity with animals, nature and the ecological system, solidarity with future generations, solidarity with all the people of the world” (Swedish Green Party, 2020: 3), but also across genders, by supporting gender-balanced party leadership, gender quotas for corporate boards, and LGBTQ rights; across socio-economic classes, by supporting strong labour unions and high-quality welfare state services; and across countries, by supporting peace, human rights, open immigration, a “more even distribution of people's consumption opportunities, nationally as well as globally” (25) and worldwide free unmonitored internet access for all (36). The party's goal is for “decisions to be made as close as possible to those affected by the decisions. Power should be exercised by those who are affected by it” (33; italics added). The party also supports “education and work that give people more power over their own lives” (18; italics added).

Similarly, the Swedish Left Party (2018: 4), founded in 1917, seeks to de-concentrate power both nationally and internationally in order to “realize a society based on democracy, equality and solidarity, a society free from class, gender and ethnic oppression.” In this party's view, “class oppression manifests itself mainly in inequality in terms of power and influence in society”; hence democracy must involve “more than universal suffrage and formal freedoms it must be made the people's power over society” (Swedish Left Party, 2018: 6, 28; italics added). Furthermore, “at local, national, regional and global levels, power needs to be transferred from transnational oligopolies and political and bureaucratic elites to democratically controlled systems” (83; italics added), in order to “shift the balance of power in society [and] strengthen the positions of the working class” (55; italics added). (See the supplementary online Appendix B and Appendix C, respectively, for more examples of how the Swedish Green Party and Swedish Left Party support power de-concentration).

Fifth, disagreements over power concentration frequently mirror preferences expressed by voters identifying with the left or right. For instance, McClosky and Chong (Reference McClosky and Chong1985: 342) found that individuals identifying with the right preferred concentration of power (in parents) in terms of “strong parental control,” while those on the left preferred a de-concentration of power (empowering children) via “an approach in which children are granted a voice in family matters.” The same was true for “sexual freedom” where they found “a precipitous decline in support for sexual freedom as we go from far left to far right on the ideological continuum” (340).

Keywords commonly associated with the political left and right likewise suggest diffusion and concentration of power. As shown in Table 1, Lakoff argues that most people's dominant metaphor for the state is the family, but conservatives on the right think it should act like a strict father promoting discipline and individual toughness in his children (with power concentrated at the top in the father) whereas progressives on the left think the state should act like a nurturing parent supportively facilitating children's development and teaching them the virtue of acting responsibly (with power shared more evenly among parents and between parents and children).

Table 1 George Lakoff's Family Metaphor Analysis of the Political Left and Right

Sources: Lakoff, Reference Lakoff2006, Reference Lakoff2016.

Sixth, if the left-right distinction is primarily an ideological one, then it necessarily involves power, as clearly evident in global debates over intellectual property between advocates of “copyright” and “copyleft.” Copyright is an exclusive “private regime,” which “excludes all outsiders from access to a firm's software assets,” whereas copyleft is a “public regime,” in which “source code is freely exchanged” (de Laat, Reference de Laat2005: 1511). The key difference between these two regimes is who has the legally authorized power to control the usage, distribution and conditions under which software is used. Under copyright, this power is narrowly concentrated in the copyright holder. Under copyleft, this power is broadly diffused so that anyone is entitled to use, distribute and modify the software as they see fit, without requiring any permission or paying any fee, while any modifications to the software code by a user must also be made publicly accessible to all.

Seventh, a focus on power concentration can help us to make better sense of where political institutions such as different forms of federalism or electoral systems lie on the left-right spectrum. On the one hand, the consequences of institutional choices often involve more uncertainty and ambiguity compared to the stated preferences of political parties and individuals, making institutions more difficult to locate on the left-right spectrum. On the other hand, certain institutional choices patently concentrate or diffuse power in specific ways, though not necessarily evenly across all political domains. For instance, when it comes to federalism, over the past 150 years Canada has arguably experienced six different models (colonial, classical, co-operative, competitive, constitutional and collaborative), with power swinging from the federal government to the provinces, then back to the centre, and back again to the provinces (Simeon and Robinson Reference Simeon, Robinson, Bickerton and Gagnon2009: 159). During this process, in the mid-twentieth century, Canada witnessed relative (but not radical) concentration of power in Domain A (the federal government) to achieve the ultimate goal of relative (but not radical) power de-concentration in Domain B (purchasing power of individuals) through building a redistributive welfare state (Simeon and Robinson Reference Simeon, Robinson, Bickerton and Gagnon2009: 159). By contrast, in the late twentieth century, there was a rightward shift to de-concentrate power in Domain A (from the federal government to provincial governments) to achieve the ultimate goal of increasing power concentration in Domain B (purchasing power and wealth of individuals).

Given the primacy of Domain B over Domain A in this instance, as Harmes (Reference Harmes2019) correctly notes, this represented a late twentieth-century shift to the political right in Canada whereby “certain wealthy individuals and large corporations” (37) seeking to concentrate capital into their own hands (by supporting “subsidies and bailouts that benefit them specifically” [38]) favoured “constraints on social democratic forms of government intervention through the creation of an exit option and inter-jurisdictional policy competition” (4). This enabled “the outmigration of wealthy individuals and firms seeking lower taxes and regulatory burdens” (4). Such competitive and adversarial approaches to federalism lie on the political right because they restrain the state's ability to tax the wealthy and fund social programs for the non-wealthy. By contrast, more co-operative forms of federalism advocated by the political centre and left often aim “to equalize fiscal capacities across subnational jurisdictions so that broadly similar levels of public goods may be provided across the country” (76). For example, “the aim of social democratic federalism . . . is to promote the policy autonomy of governments by limiting ‘harmful’ forms of policy competition” (57) while advancing “social justice through macroeconomic demand management, wealth redistribution, and the correction of market failures” (70). In other words, more leftist models of federalism aim to de-concentrate purchasing power and thereby reduce inequality in living standards across the population. Thus, although social democratic actors may focus on centralizing policy making (in the federal government, as opposed to provincial or local governments) to achieve their welfare state goals, their overarching motivation is to de-concentrate purchasing power.

Eighth, in response to those who might still argue that equality is the key issue of contention here, one must ask “what kind of equality” and “whose equality” is at stake? A major problem we face in today's world is that nearly every political actor professes support for some type of equality regardless of where they are located on the left-right spectrum. Yet they do not all mean the same thing when they claim to support equality. As Amartya Sen (Reference Sen1995: 15) has demonstrated, almost all value positions call for some form of equality, and even “critiques of egalitarianism tend to take the form of being—instead—egalitarian in some other space.” For instance, Sen (Reference Sen1995: 13) notes how someone associated with the political right, such as Robert Nozick, “may not demand equality of utility or equality of holdings of primary goods, but he does demand equality of libertarian rights—no one has any more right to liberty than anyone else.” Likewise, Lakoff (Reference Lakoff2016: 60) identifies various forms of equality that a political group can pursue such as equality of distribution, equality of opportunity, equal distribution of responsibility or equal distribution of power. As Bobbio (Reference Bobbio1996: 60–61) clarifies, “The concept of equality is relative, not absolute. . . . In other words, once the principle of equality has been accepted, no proposal for redistribution can fail to respond to the following three questions: Between whom? Of what? On the basis of which criteria?”

Thus, in the realm of politics, the concept of equality always carries with it some sense of ambiguity. For instance, should all states be equal in the international system? Or should the political power of states be proportional to the size of their population? Or should all individuals in all countries be equal in some shape or form? While scholars and the public are presumably divided on their preferences and answers to these questions, the most general limitation of thinking about politics strictly in terms of equality is that we do not know on which dimension people are or ought to be equal. Should they all have equal haircuts, equal paychecks, equal student-teacher ratios in school, equal numbers of voters in each voting district within a country (or across all countries), equal television advertising time during political campaigns, equal numbers of nuclear weapons to deter an invasion, and so on? Because equality varies across contexts, I argue that the type of equality/inequality most pivotal to the left-right continuum is equality/inequality in the distribution of power. Since equality is a malleable concept, the political right may not be opposed to, or even favour, certain types of equality, but where it strongly disagrees with the political left is that it opposes equality of power, since that is antithetical to its core belief that hierarchy serves a necessary and proper function within all societies, whether based on meritocracy, inheritance, fate, divine will, moral righteousness or some other criteria.

Application to Political Issue Domains

Having defended my claim that power diffusion/concentration is the underlying source of left-right divergence, I will now argue that it is important for us to recognize that those who prefer concentration or diffusion of power within a particular issue domain may not do so in another domain. Domains play a crucial role in politics because human beings are complex in their thinking and may feel that what “is justifiable in some sphere is unacceptable in others” (Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2011: 21). For instance, some political parties may favour de-concentration of economic power in their own nation, such as those aiming to achieve “socialism in one country,” while simultaneously resisting de-concentration of power internationally among countries, genders or species.

I will now illustrate the utility of my “one dimension, multiple domains” framework for comparing political parties across the left-right spectrum through a case study of contemporary Sweden. Sweden was chosen because it is a well-established multi-party unitary democracy that has pragmatic and differentiated political parties located across the entire left-right spectrum, as opposed to catch-all or personalist parties. As Oscarsson and Holmberg (Reference Oscarsson, Holmberg and Pierre2016) explain, it is a social democratic country that has a long history of free competition between both socialist and bourgeois political parties:

A traditional left-right dimension has been structuring party competition and voting behavior in Sweden since at least the 1880s, and it is still overwhelmingly dominant in explanations of political change. The mental representation of parties lined up from left to right along a single continuum is predominant also among younger generations. Left-right ideological predispositions keep bringing stability, order, and congruence to political attitudes and behavior, perhaps more so than in any other political system. (260–61)

As they further note, over time, new political issues have “started out as oblique dimensions in their own right, but have all ended up more strongly correlated, and thus more aligned with, the ‘imperialist’ left-right dimension. The absorptive power of the spatial distinction is exceptional in the Swedish case” (262).

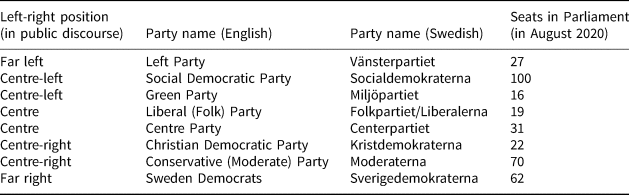

Featuring proportional representation elections and a low 4 per cent threshold of exclusion, Sweden's national parliament includes eight political parties across multiple positions on the left-right spectrum (see Table 2). In this context, we would expect to see political parties exhibiting more consistent and coherent ideologies than under smaller two- or three-party systems, as in many Canadian provinces where parties often stake out certain positions just to create a contrast with their rival, even if the positions do not appear to cohere with their overall program (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015). The choice to focus on Sweden is also well suited for comparing party ideologies because Swedish governments regularly involve explicit or tacit multi-party coalitions, and left-right divergence has long been a primary axis of inter-party competition (Aylott, Reference Aylott and Pierre2016).

Table 2 Major Swedish Political Parties across the Left-Right Spectrum

Comparing discursive claims made in Swedish party manifestos and other policy pronouncements over the past decade between 2011 and 2020 (see Appendix A for a full list of sources), I identified parties’ relative positions across three issue domains where left-right divergence tends to be prominent (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015: 44): (a) taxation and economic policy, (b) foreign policy and immigration and (c) social policy and the welfare state. According to my theoretical expectations, Sweden's leftist parties should be the most supportive of power diffusion, with emphasis on power de-concentration diminishing among parties as one moves toward the right along the left-right spectrum.

Taxation and economic policy

Starting with taxation and economic policy, the Swedish Left Party (LP) highly emphasizes de-concentrating purchasing power through progressive taxation to “redistribute between rich and poor” (LP, 2020a) and to “reduce income and wealth inequality” (LP, 2011: 22). Supporting full employment, strong labour unions and social ownership via a greater share of worker-owned co-operatives (LP, 2018), the party advocates de-concentrating business ownership and for “the tax on large fortunes, large inheritances and gifts as well as capital income to be raised” (LP, 2020a).

Though not calling for de-concentration of business ownership, the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SDP) supports welfare and employment for all (SDP, 2020a), stating that “welfare needs to be put before new tax cuts” (SDP, 2011a; see also SDP, 2011b). Similarly, the centre-left Swedish Green Party (GP) has endorsed strong welfare, opposed tax cuts and sought to “reject a tight fiscal policy where the overriding goal is to lower the tax burden,” while also calling for a “need to stabilize government finances and sound public-funded welfare” (GP, 2011a).

In contrast, the more centrist Liberal (Folk) Party (FP) has placed less emphasis on power diffusion, preferring “lower taxes on labour and higher taxes on environmentally damaging activities” (FP, 2011a), in order to make it “cheaper and easier to employ” people (FP, 2020). Meanwhile the aptly named Centre Party (CP) has asserted that “policies must not be formulated so that they stifle people's spirit of enterprise with exaggerated regulation or taxation. Neither must policies leave people so insecure that no one dares to invest or try out new ideas” (CP, 2011a: 7).

The centre-right Christian Democratic Party (CD) has placed comparatively greater emphasis on “private sector and individual entrepreneurship” (CD, 2011a), arguing that “taxation risks impairing the economy and could lead to unhealthy economic behaviour” (CD, 2011b: 45). Likewise, the Conservative (Moderate) Party (MP) has been supporting “tax cuts” to “help create new jobs, so that people can be helped out of benefit dependency and given opportunities to earn a decent living” (MP, 2011a). Lastly, the far-right Sweden Democrats (SWD) championed “work as being the only sure means to achieve sustainable individual as well as general prosperity” (SWD, 2011a) but they also sought to only “lower taxes for pensioners . . . rather than general income tax cuts” (SWD, 2011b).

Thus, across the left-right spectrum, we found greater emphasis on de-concentrating purchasing power and ownership of the means of production on the left. In comparison, more emphasis on work and lowering taxes appeared on the right, thereby implying support for a greater concentration of purchasing power among income earners (and the wealthy), since many people (for example, children, students, retirees, disabled people, housewives, etc.) are unable to work (or receive much remuneration) because of their position in the lifecycle, health impairments, care responsibilities or discrimination in employment markets.

Foreign policy and immigration

In the domain of foreign policy and immigration, Sweden's Left Party once again strongly prioritized power de-concentration across nations and individuals via “international solidarity” and “women's liberation” to “even out the gaps between poor and rich people and countries and between women and men through a fairer global world order” (LP, 2020b). Though less radical, the Social Democratic Party likewise emphasized international solidarity: “We pledge our solidarity not only to people within our borders, but also people around the world” (SDP, 2011c). Supporting both open immigration and mother-tongue education (GP, 2011b), the Green Party emphasized not only international peace and solidarity but also solidarity with future generations, immigrants and the environment, stating that “our commitment is driven by a love of nature and a strong sense of solidarity with the people living today and with coming generations” (GP, 2011c: 2).

Meanwhile, centrist parties displayed less emphasis on global solidarity. The Liberal (Folk) Party sought for Sweden to join NATO, and it supported immigration but not mother-tongue education: “Work, self-support and Swedish [language] are the key to integration. Sweden will be a country where we take advantage of the potential and motivation of people with foreign backgrounds” (FP, 2011b). The Centre Party similarly supported “freedom, democracy and human rights” but sought to eliminate special supports for immigrants and instead “ensure that all basic policies are more inclusive” (CP, 2011b: 1).

The centre-right parties put comparatively greater focus on security, defence and threats. The Christian Democratic Party supported advancing “a market economy that respects the environment and social factors, and that combines freedom and security” (CD, 2011a). The party also favoured “carrying out more deportations” of migrants and having “more detention centers” (CD, 2020). The Conservative (Moderate) Party emphasized protecting the “world order that prevailed during the post-war period,” safeguarding “Sweden's security, freedom and independence” and defending “Sweden's various interests in the international arena” (MP, 2020). The party also took a more selective position on immigration: “Nobody has the right to ask a country to provide for them if they lack a legitimate need for protection” (MP, 2011b: 38).

Lastly, the far-right Sweden Democrats opposed most forms of immigration, calling for “a safe and protected border to keep organized crime, human trafficking and terrorism away” while supporting forms of international co-operation that “puts the conditions for Swedish workers and taxpayers first” (SWD, 2020b). To sum up, in this domain, parties on the right were more nationalistic, emphasizing defence and security (of status quo arrangements), which would protect/sustain existing power concentrations. By contrast, parties on the left were more supportive of diffusing economic and political power to immigrants, foreigners, women, the environment and future generations.

Social policy and the welfare state

On social policy and the welfare state, as expected, leftist parties focused heavily on diffusing power. Sweden's Left Party championed both free universal education and curriculum reform to support power diffusion by promoting equality and “societal” democratization (LP, 2011: 23). Strongly contesting “racism” and “patriarchy,” the Left Party insisted that no one should be excluded from Sweden's generous welfare policies. Centre-left parties also supported reducing power disparities via welfare financing from general taxation. The Social Democratic Party emphasized welfare universality, “stopping the pursuit of profit in welfare” (SDP, 2020b) and upholding “values of solidarity, compassion, justice and equality” (SDP, 2011d). With power diffusion across generations and genders in mind, the party prioritized becoming “the world's best country for children” (SDP, 2011e), “best country in which to grow old” (SDP, 2011f) and for “parents to make more or less equal use of the parental insurance scheme” (SPD, 2011e). Inter-generational and gender-based power diffusion was likewise supported by the Green Party, as was respect for many kinds of diversity, including LGBTQ lifestyles: “The welfare state's security system must be inclusive, general and robust” (GP, 2020).

The more centrist Liberal (Folk) Party has emphasized a supportive social policy, though with less attention to solidarity and more emphasis on developing “choices and individual autonomy” in welfare programs (FP, 2011c). Meanwhile the Centre Party has argued in favour of “people giving one another mutual support” (CP, 2011a: 3). Rejecting special treatment for both the deprived and privileged, the party maintained that “each person has the same rights and obligations, regardless of gender, outlook on life, sexual preference, dwelling, ethnic or social background” (CP, 2011a: 3).

Centre-right parties exhibited comparatively less interest in using social policies to diffuse power to the less well-off, while they were more supportive of jointly funded welfare and having welfare “choices,” which would likely facilitate concentration of power, as more desirable choices are often only available to those with additional resources in terms of time, money and transportation access (Bobbio, Reference Bobbio1996: 75). Emphasizing family cohesion, the Christian Democratic Party championed parental and school choice. Similarly, the Conservative (Moderate) Party advocated for health services to be “characterized by diversity” (MP, 2011b: 61) while opposing equal allotments by gender in parental insurance (MP, 2011b: 74) and wanting unemployment insurance to become mandatory and in the form of “an adjustment insurance rather than a means to support oneself long-term” (36), thereby making it less an instrument of progressive redistribution.

Thus, on social policy, right-of-centre parties generally demonstrated relatively greater support for traditional male-dominant heteronormative family structures, and they also had fewer women in their parliamentary delegations compared to the left. This pattern was shared by the far-right Sweden Democrats, who wanted lower taxes for pensioners (essentially reinforcing age hierarchy in society) and for the state to “take the main responsibility for schools,” although “parents should be given the opportunity to choose school and type of school” (SWD, 2011a: 23). Exhibiting a xenophobic and anti-Islamic orientation (“we will never give way to Islamism”), the party also wanted to exclude non-citizens from various welfare services (SWD, 2020a).

To sum up, on all three issue domains examined here, the far-left party sought the most power diffusion. Moreover, this emphasis generally diminishes as one moves toward parties to the right. This finding was rather consistent across all eight parties in three separate issue domains, thereby supporting my contention that the left-right divide stems primarily from the unidimensional factor of support/opposition for power de-concentration.

Separately examining different issue domains also enabled us to develop a more nuanced understanding of party ideologies, as there were occasional instances where a party's preference in one domain was to the left or right of its stance in other domains, though usually not by a great distance. The most notable cases of this were the centre-left Green Party coming out more to the left on foreign policy and certain aspects of social policy issues than the Social Democratic Party, while the otherwise far-right Sweden Democrats appeared to hold a more centrist position compared to the Conservative (Moderate) Party on economic policy.

As would be expected when examining a complex multi-party system, we also found parties placing varying levels of emphasis on different issue domains. For instance, support for relative power concentration on a class basis was more prevalent in the discourse of the Conservative (Moderate) Party, whereas support for power concentration on the basis of ethnicity/race/nationality was most prominent in the discourse of the Sweden Democrats. On the left side of the spectrum we found considerable support for relative power diffusion on the basis of class by the Social Democratic Party; gender, race and class by the Left Party; and generation, nationality and species by the Greens.

Conclusion

In this article, I have argued in favour of labelling political parties seeking a diffusion of power as on the left and those seeking a concentration of power as on the right. As mentioned above, my claim is not that equality is unrelated to left-right divergence but rather that the aspect of equality most relevant to the left-right divide in the twenty-first century is equality of power. Moreover, through comparative analysis of political party pronouncements, I found convincing evidence supporting my theoretical expectation that de-concentration of power is a primary aim of contemporary leftist parties in democratic countries, especially those that adopt the name “Left Party.” By contrast, a counter-mobilization to maintain power's relative concentration in various issue domains was evident among parties to the right, especially in the economic and foreign policy/citizenship domains via the defence of capitalism (for example, concentrated ownership of the means of production) and exclusions/hierarchy on the basis of nationality/citizenship.

In conclusion, my “one dimension, multiple domains” approach adds important nuance to dominant understandings of the left-right spectrum while allowing us to also recognize that political parties may differ in preferences over specific issue domains. This framework therefore provides a way to make sense out of political leanings that might otherwise seem hypocritical or contradictory. It can also help to clear up certain misconceptions people might have about politics that have arisen from commonly used labels that understate or disguise the complexity of reality. Lastly, this framework holds the potential for providing a conceptual guidepost for future research to assess the degree to which parties’ attitudes toward the diffusion of power, in general, as well as in specific issue domains, evolve over time. Thus, I argue that this new conceptualization will help both political analysts and political actors to gain a clearer perspective on how political parties are comparatively located in ideological space.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to kindly express his gratitude to Neha Navlakha for research and translation assistance and to Roni Kay O'Dell, Manfred Steger, Jean-Philippe Thérien, and the journal's three anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423921000408

Appendix A: Sources of Swedish Political Party Quotes

Notes: 2011 sources were collected in March–April 2011, with quotations translated by a research assistant.

2020 sources were collected in April–July 2020, with quotations translated via Google translation software.

Centre Party (CP)

CP 2011a. “Centre Party Statement of General Policies.” http://www.centerpartiet.se/Documents/otherlanguages/ideprgeng.pdf

CP 2011b. “Centre Party on Integration.” http://www.centerpartiet.se/Documents/Partistammor/2011/c_st%C3%A4mma2011_Del1_10_

Christian Democratic Party (CD)

CD 2011a. “Christian Democrats on Business and Work.” http://www.kristdemokraterna.se/VarPolitik/Politikomraden/ForetagOchArbete

CD 2011b. “Christian Democrats' Policy Programme.” http://www.kristdemokraterna.se/VarPolitik/Principprogram.aspx

CD 2020. “Christian Democrats on Migration and Integration.” https://kristdemokraterna.se/migration-och-integration/

Conservative (Moderate) Party (MP)

MP 2011a. “Conservative Party – English Summary.” http://www.moderat.se/web/In_English.aspx

MP 2011b. “Conservative Party Policies.” http://www.moderat.se/MediaBinaryLoader.axd?MediaArchive_FileID=b657e40e-671f-4dd2-

MP 2020. “Conservative Party on Foreign Policy.” https://moderaterna.se/utrikespolitik

Green Party (GP)

GP 2011a. “Green Party on Taxation.” http://www.mp.se/templates/mct_177.aspx?number=187831

GP 2011b. “Green Party on Integration.” http://www.mp.se/templates/Mct_177.aspx?number=214332

GP 2011c. “Green Party on Foreign Policy.” http://www.mp.se/files/213600-213699/file_213617.pdf

GP 2020. “Green Party on Welfare.” https://www.mp.se/om/partiprogram/valfarden

Left Party (LP)

LP 2011. “Left Party – 2008 Party Programme.” http://www.vansterpartiet.se/images/stories/media/dokument/politiskaprogram/partiprogram_08_inlaga.pdf

LP 2018. “Left Party – 2018 Party Programme.” www.vansterpartiet.se/resursbank/partiprogam/

LP 2020a. “Left Party on Taxes.” https://www.vansterpartiet.se/politik/skatter/

LP 2020b. “Left Party on Foreign Policy.” https://www.vansterpartiet.se/politik/utrikespolitik/

Liberal (Folk) Party (FP)

FP 2011a. “Liberal Party on Taxation.” http://www.folkpartiet.se/Var-politik/Snabba-fakta/Gron-skattevaxling/

FP 2011b. “Liberal Party on Integration.” http://www.folkpartiet.se/Var-politik/Vara-viktigaste-fragor/Integration/

FP 2011c. “Liberal Party on Elder Care and Pensions.” http://www.folkpartiet.se/Var-politik/Vara-viktigaste-fragor/Vard-och-omsorg/

FP 2020. “Liberal Party on Taxes.” https://www.liberalerna.se/politik/skatter/

Social Democratic Party (SDP)

SDP 2011a. “Social Democratic Party on Taxes.” http://www.socialdemokraterna.se/Var-politik/Var-politik-A-till-O/Skatter/

SDP 2011b. “Social Democratic Party on Growth and Entrepreneurship.” http://www.socialdemokraterna.se/Var-politik/Var-politik-A-till-O/Tillvaxt-och-foretagande/

SDP 2011c. “Social Democratic Party on Foreign Policy.” http://www.socialdemokraterna.se/Internationellt/Var-internationella-politik/Internationellt-A-O/Bistand1/

SDP 2011d. “Social Democratic Party on Welfare.” http://www.socialdemokraterna.se/Var-politik/Var-politik-A-till-O/Valfarden/

SDP 2011e. “Social Democratic Party on Housing.” http://www.socialdemokraterna.se/upload/Central/dokument/pdf/Andra%20spr%C3%A5k/Engelska/slutv%20179066%20bra%20bostad_Engelska_MMQ.pdf

SDP 2011f. “Social Democratic Party on Family Policy.” http://www.socialdemokraterna.se/upload/Central/dokument/pdf/Andra%20spr%C3%A5k/Engelska/slutv%20178937%20familjepotitik_Engelska_MMQ.pdf

SDP 2020a. “Social Democratic Party on the Economy.” https://www.socialdemokraterna.se/var-politik/a-till-o/ekonomi

SDP 2020b. “Social Democratic Party on Welfare.” https://www.socialdemokraterna.se/var-politik/a-till-o/valfard

Sweden Democrats (SWD)

SWD 2011a. “Sweden Democrats' Principal Programme.” https://sverigedemokraterna.se/files/2011/03/principprogram_2011.pdf

SWD 2011b. “Sweden Democrats Policies from A to Z.” https://sverigedemokraterna.se/vara-asikter/var-politik-a-till-o/

SWD 2020a. “Sweden Democrats – What We Want.” https://sd.se/vad-vi-vill/

SWD 2020b. “Sweden Democrats on Foreign Policy.” https://sd.se/vad-vi-vill/utrikespolitik/