The purpose of this article is to remind readers and commentators that utilitarianism could still provide a basis for moral and political choices in bioethics and elsewhere. After a brief historical overview, I will describe where I see that the “justice turn” in normative thinking has left us in terms of views on ethics and social policy. I will then outline, in some detail, my own quarter-of-a-century-old theory of liberal utilitarianism and suggest that it could be helpful in bioethics-related decisionmaking. To conclude, I will list some of the main reasons for not taking my suggestion seriously and invite comments for making the approach more palatable, feasible, and applicable.

Utilitarianism and its Rivals

We need to make decisions, and we need rules, or principles, or guidance—an algorithm—for making them. In medicine, healthcare, social services, government, and politics, the procedure should be widely acceptable because in these areas, the decisions we make are public. In private life and in business, different rules may apply, but we expect public decisions to be “good” in some important sense—reliable, sound, perhaps scientific to some extent, rational as we understand it, and reasonable.

For quite some time in the 19th and 20th centuries, one good contender for a solid decisionmaking criterion was utilitarian—public decisions should benefit as many as possible and as much as possible.Footnote 1 , Footnote 2 , Footnote 3 , Footnote 4 , Footnote 5 This was in contrast with the traditional and economic views, according to which public decisions ought to benefit society’s upper crust or ought not to interfere with the dealings of capitalists with one another and with their workforce.Footnote 6 In the quickly industrializing modern world, however, utilitarianism in one form or another permeated much of public decisionmaking in the more affluent countries.

Alongside with the empiricist, welfare-based utilitarian tactic, other rationalist, duty- and community-based approaches emerged and developed.Footnote 7 , Footnote 8 , Footnote 9 , Footnote 10 These experienced many twists and turnsFootnote 11 , Footnote 12 , Footnote 13 before poststructuralism and postmodernism started to undermine their credibility.Footnote 14 In the meantime, another contender, rights-based political thinking, had emerged with national and international declarations.Footnote 15 , Footnote 16 An ambivalent alliance between postmodernism and rights-based ethics gave rise to late-20th-century forms of feminism and to other policies of identity and recognition.Footnote 17 , Footnote 18 , Footnote 19 , Footnote 20 , Footnote 21 , Footnote 22

During the “justice turn” in moral and political thinking that began in the late 20th century (to be explained in the next subsection),Footnote 23 , Footnote 24 , Footnote 25 , Footnote 26 consequentialist theories encountered much criticism and underwent several permutations. As a result, we can now choose from a variety of options. Nonconsequentialist alternatives include rights ethics, virtue ethics, strict duty ethics, and a number of practical and positional approaches.Footnote 27 Cautious consequentialists can moderate their insistence on maximizing well-being by side constraints—by saying that we ought to aim at the greatest calculable good only within certain predetermined limits.Footnote 28 , Footnote 29 Less cautious consequentialists in bioethics have attracted the label “bioutilitarian.”Footnote 30 , Footnote 31 The diversification, however, has come with a cost. Although relativism in some sense can be a healthy outlook,Footnote 32 , Footnote 33 some of the boundaries between views have become uncrossable, and this has led to impolite disagreement, which is not conducive to reasoned communication.

Justice and its Alternatives

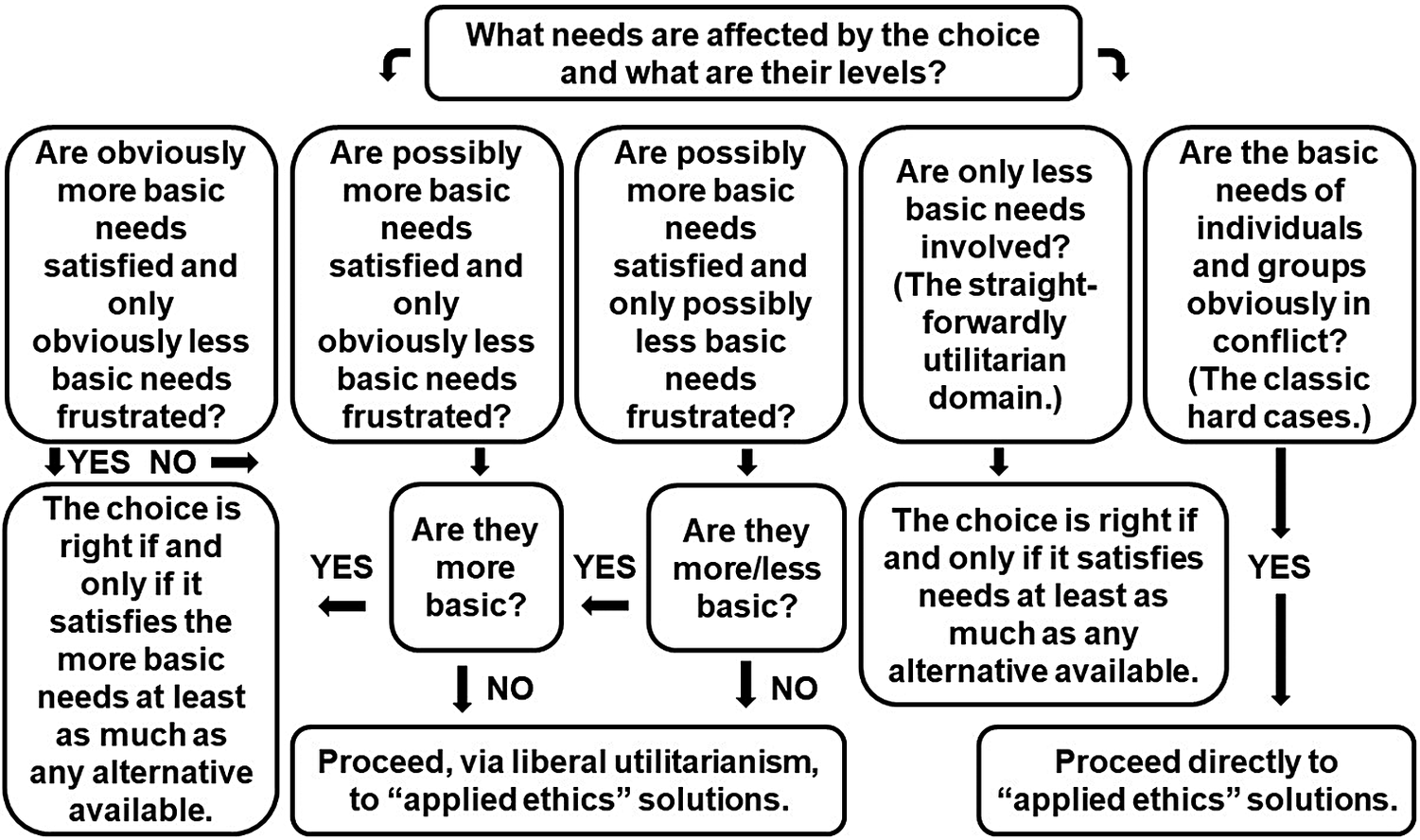

Figure 1 presents a map of justice and morality that I have devised to illustrate the current situation.Footnote 34

Figure 1. Theories of justice and morality.

Theories of justice divide into six main categories according to their takes on three dimensions: private or shared control of property (means of production); the universal or positional reach of norms and values; and spontaneous social development or calculated, deliberate political change. The doctrines at the extremes are libertarianism (private property, individuals’ rights),Footnote 35 socialism and its allies (shared property, social responsibility),Footnote 36 , Footnote 37 , Footnote 38 , Footnote 39 , Footnote 40 the capabilities approach (universal capability promotion and human rights),Footnote 41 , Footnote 42 , Footnote 43 , Footnote 44 , Footnote 45 care and special relations tactics (positional recognition of differences, identities, and their meaning),Footnote 46 communitarianism (spontaneously formed communal tradition and roles),Footnote 47 , Footnote 48 and utilitarianism (calculated maximization of well-being or preference satisfaction).Footnote 49 As far as traditional Western ethical theories are concerned, consequentialism resides on the right in Figure 1. Deontological doctrines range from top to some distance to the bottom in the middle, and teleological creeds occupy the left, with extensions in all directions. Teleology, which is in a way the origin of Western moral philosophy, has left residue in all subsequent efforts. The more contemporary, poststructural, and postmodern thinking mostly finds its place in the bottom-left corner,Footnote 50 with notable exceptions when feminism forms bonds with the communitarian and capabilities approaches.Footnote 51

After my first presentations of this map of justice in 2011,Footnote 52 Western societies have changed. I introduced the map as an illustration of the many voices that we should listen to in political discussions.Footnote 53 Now it has become a description of battle lines between ideological groups, who all claim that they have the one truth on their side.Footnote 54 In an early public airing of the model, I actually suggested that ruling out libertarianism (as the evil herald of global capitalism) would be enough for everyone else to find a common tune.Footnote 55 How wrong I was. In just a few years, for whatever reasons, the until-now-relatively-sane part of the world—the liberal democracies of the West—seems to have mentally collapsed. Populists who are well on their way toward fascism lead some countries in the European Union; one country leaves the Union under illusions of past grandeur, and many think that the United States of America has descended into an unprecedented era of post-truth politics.Footnote 56 These are all expressions of communal extremism and nationalism, and they isolate their advocates to the top-left corner of Figure 1. Critics of these views in the care (bottom left) and capability (top right) camps, in their turn, have found the truth in the voices of previously oppressed or forgotten social sections and intersections or in new technologies that solve all humanity’s problems.Footnote 57 , Footnote 58 , Footnote 59 Accusations of populism, elitism, reactionism, and overpoliticization abound and sensible dialogue across the boundaries seems to have become impossible.

The situation is worth attention, and we sorely need a compromise view that can take into account as many rival concerns as possible.Footnote 60 John Rawls attempted this in his doctrine of justice as fairness,Footnote 61 , Footnote 62 , Footnote 63 as did Jürgen Habermas with his theory of communicative action,Footnote 64 , Footnote 65 , Footnote 66 and Martha Nussbaum with her version of the capability approach.Footnote 67 , Footnote 68 , Footnote 69 Rawls tried to find a balance between libertarianism and socialism, Habermas, between universalism (the viewpoint of all or anybody) and positionalism (the viewpoint of the particular person we communicate with), and Nussbaum’s account contains elements of at least liberalism (top right in Figure 1), Aristotelianism (left), and Marxism (bottom middle).Footnote 70 The exact locations of the three compromise views on the map of justice would merit an examination of its own, as would the advantages and disadvantages of applying them to the current political situation. Here, it suffices to observe that they all reject utilitarianism (bottom right), although they all also pursue the general good in one sense or another. Rawls argues that people would not choose utilitarianism because it could cancel certain benefits that his own two principles would guarantee to them.Footnote 71 Habermas’s complaint is that utilitarians conflate interests and values.Footnote 72 Nussbaum rejects utilitarianism for satisfying adaptive preferences—ones that oppressive structures force upon individuals.Footnote 73 All these are, however, criticisms against a certain type of consequentialism, namely rigidly aggregative average preference utilitarianism. This leaves the possibility that some other version of the creed could fare better in the race for the most eligible compromise view on justice. I suggest that my account of liberal utilitarianism (“LU” in Figure 1), developed a long time ago and long forgotten, fits the bill.Footnote 74

Interlude

On December 13, 1990, after the successful examination of my doctoral thesis at the University of Helsinki, I was having dinner with professors John Harris (my examiner) and Timo Airaksinen (chair of the panel), when the idea of writing a book on liberal utilitarianism struck me.Footnote 75 The professors accused my doctoral work (10 loosely related bioethics articles thrown together with a makeshift methodological introduction) of ethical relativism because, in the method part, I appeared to deny the existence of absolute moral truths.Footnote 76 As I had toyed with the idea of nonaggregative and autonomy-embracing consequentialism before,Footnote 77 , Footnote 78 , Footnote 79 liberal utilitarianism seemed like a feasible choice. Let me outline the view that I produced, starting with the problems in preceding theories that I endeavored to solve.

Issues in Classical Utilitarianism

Classical utilitarianism operates on three axioms: the maximization of happiness; the definition of happiness as pleasure and absence of pain; and impartiality between individuals in the calculation of happiness.Footnote 80 In political and healthcare decisions, abiding by these rules could make life easy, in theory at least. Just list all the pleasure and pain factors of the situation, whip out your calculator, and the screen tells you what your best choice is. Unfortunately, however, all three axioms, separately and in combination, are vulnerable to general objections and imaginary counterexamples, which philosophers from other schools of thought have been keen to provide.

Repugnant Conclusion

If it were in our power to decide the number of world’s inhabitants in the future, the maximization of happiness would require us to prefer, counterintuitively, huge populations of almost unhappy sentient beings to smaller populations of happier ones. This is a nonspeciesist formulation of Derek Parfit’s “repugnant conclusion” argument or “mere addition paradox.”Footnote 81 Utilitarian philosophers had allegedly solved the paradox before my time by saying that our decision criterion in this case should be the average, not total, happiness of the population.Footnote 82

Utility Monster

Switching from total to average utilitarianism is not, however, a sustainable solution. We may have to choose between a population in which happiness extends equally between individuals and a population in which one individual devours all the happiness or all the resources needed for producing happiness. The statistical contentment per capita can be the same in the two models, so average utilitarianism cannot tell them apart, although intuition would probably favor the more equal model. This paradox, made famous by Robert Nozick,Footnote 83 has to be resolved in any better version of utilitarianism.

The response to the utility monster challenge begins with the realization that we cannot combine the straightforward accumulation and a subjective definition of the good without causing problems.Footnote 84 Since, moreover, accumulation, or maximization, is the basic tenet of utilitarianism, the response to this challenge has to be in the redefinition of the good. A proper choice of value here should also answer the other standard axiological questions that face the doctrine. Do we ignore higher values if we count only simple hedonistic factors? Is a psychopath’s pleasure for torturing people truly as important as the pain induced in the process? What if people get pleasure out of adaptive things, things that they choose only because they are easily available?Footnote 85 , Footnote 86 In the late 19th century, Herbert Spencer presented one solution by suggesting that the free and socially unencumbered evolution of a perfectly and voluntarily altruistic humankind is the maximum good that we should pursue.Footnote 87 This idea of defining the good objectively did not catch on,Footnote 88 but it partly inspired a criticism of classical utilitarianism that prompted it to develop further.

Naturalistic Fallacy

In his critical contribution, G. E. Moore bundled together Spencer’s evolutionism and the hedonism of Jeremy Bentham,Footnote 89 John Stuart Mill,Footnote 90 and Henry Sidgwick,Footnote 91 called their ethics naturalistic, and reproached them all for committing what he called the “naturalistic fallacy.”Footnote 92 Essentially, he argued that the good always eludes any attempts to define it in terms of experiences, physiology, biology, and the like. In the end, we can always ask, “Yes, it is pleasurable—but is it good?” and the meaning department in our minds understands that this is a valid question and the two things conceptually separate from each other.Footnote 93 Moore himself said that we must know what is good intuitivelyFootnote 94 and continued, “By far the most valuable things, which we know or can imagine, are certain states of consciousness, which may be roughly described as the pleasures of human intercourse and the enjoyment of beautiful objects.”Footnote 95 This view impressed Moore’s fellow philosophers and augured, in English-speaking countries, a metaethical turn, but it did not offer the clear guidance for utilitarian decisionmaking that he himself seemed to require in his later work.Footnote 96 Half a century later, preference utilitarianism and its cronies steered the course back to practical applicability,Footnote 97 , Footnote 98 , Footnote 99 , Footnote 100 , Footnote 101 , Footnote 102 , Footnote 103 but by that time, condemnations by Rawls and others had already undermined the theory’s wider appeal.Footnote 104 , Footnote 105 , Footnote 106

Unprovability

Moore’s view, together with another question raised by classical utilitarianism, might show the way forward, though. Philosophers have complained that the doctrine’s axioms are unprovable, which means that it does not have a solid foundation.Footnote 107 Bentham, Mill, and R. M. Hare responded to this pragmatically, conceptually, linguistically, and logically.Footnote 108 , Footnote 109 , Footnote 110 Bentham claimed that all theories of ethics eventually find their basis in the happiness of the greatest number. Why should we perform our duties? Because it is conducive to the greatest happiness. Why should we be virtuous? Because it is conducive to the greatest happiness. And so on. Mill thought that since all individuals want their own happiness, it stands to reason that collectively everybody wants everybody’s happiness. Hare maintained that “I ought to do this” means, in the English language, “This maximizes universal preference satisfaction.” Bentham’s idea begs the question (“No, I perform my duties because they are my duties” is still a possibility), Mill probably committed a fallacy of composition (I like my dreams, but not everybody likes everybody else’s), and Hare’s suggestion just sounds plain odd (although I will return to it shortly).

Bentham had another suggestion, however, which might fare better. He noted, namely, that no ethical theory can claim to substantiate its first principles because, as first principles, they are the end of the line and we just have to assume their validity. In a purely deductive model, this would be just assertion. “These are my axioms, and you cannot challenge them.” Add, however, a degree of falsifiability, and the proposal becomes hypothetico-deductive and almost scientific. Sidgwick, who preceded Moore in Cambridge, set out to do just that in his own account.Footnote 111 He formulated three ethical views—dogmatic intuitionism, universal hedonism, and ethical egoism—and tested them against the intuitions of coherence, justice, prudence, and the universality of goodness.Footnote 112 In a way, Hare’s linguistic method has a similar basis. His idea was that although people’s first answer to the question “What does ‘I ought to do X’ mean?” would not be “X maximizes universal preference satisfaction,” a sufficiently long series of questions and answers would in the end elicit this response from any standard English speaker.Footnote 113

Putting together Bentham’s defense of the unprovability of first principles, Moore’s observation concerning the undefinability of the good, and Sidgwick and Hare’s idea of testing ethical theories against moral and linguistic intuitions should provide the methodological makings of a better utilitarianism. The logic is to formulate and postulate a theory and then see how it fares in challenging imaginary and real-life situations. This is where the rest of the objections and counterexamples presented by the opponents of utilitarianism come in.

Infeasibility

Calculating the consequences of our individual actions from here to eternity is impossible and, as George Berkeley noted already in 1712, even if it were possible, it would take too much time and energy to be in any way practicable.Footnote 114 , Footnote 115 , Footnote 116 Insofar as we intend utilitarianism to be a tool for ethical decisionmaking, we need to address this issue somehow. Suggested solutions include rule utilitarianismFootnote 117 and Hare’s related two-tier model,Footnote 118 but these have had their critics.Footnote 119 , Footnote 120 , Footnote 121

Morality, Moral Integrity, Justice, and Self-Sacrifice

Applying the classical utilitarian tenets of maximization, impersonal definition of value, and strict impartiality to real-life situations sometimes requires us to favor strangers at the expense of our own family and friends, to act in ways that traditional outlooks see as immoral or unjust, or sacrifice ourselves for the good of total strangers. Utilitarians can defend themselves, to an extent, by saying that this is what public decisionmaking is about: going beyond favoritism, archaic moral attitudes, and selfishness. Certain imaginary examples show, however, that this response is not always sufficient.

In Philippa Foot’s “Trolley problem,” a trolley will hit and kill five people on its track unless you steer it to another track, where it will hit and kill one person. Classical utilitarianism seems to require you to do so, although this forces you to contribute to a moral wrong.Footnote 122 In Bernard Williams’s “Jim and the Indians” case, a public authority prompts an innocent bystander, Jim, to kill a local person, as otherwise the public authority would kill not only this person but also 19 others. According to classical utilitarianism, it appears to be Jim’s duty to comply, although this would dent his moral integrity.Footnote 123 In H. J. McCloskey’s “Sheriff” example, the only way in which the local law enforcement officer can prevent lethal riots provoked by a heinous crime is to arrest and execute an innocent person.Footnote 124 Again, utilitarianism seems to make this injustice the law enforcement officer’s duty. Igor Primorac added to this the angle of excessive self-sacrifice by observing that anyone whose wrongful execution would stop the rioting actually has a utilitarian obligation to volunteer for the task.Footnote 125 These examples and others like them offer good grounds for testing moral theories, including mine.

Liberal Utilitarianism

The theory of liberal utilitarianism, as I devised it, operates on six principles. They are:

-

1) The greatest need satisfaction principle.

An act, omission, rule, law, policy, or reform is the right one if and only if it produces, or can be reasonably expected to produce, at least as much need satisfaction as any other alternative which is open to the agent or decisionmaker at the time of the choice.

-

2) The principle of hierarchical needs.

When the need satisfaction produced by various action alternatives is assessed, those needs which are hierarchically at a less basic level shall be considered only if the action alternatives in question do not, or cannot be expected to, produce an effect upon the satisfaction of needs at a more basic level.

-

3) The principle of other-regarding need frustration.

When the need satisfaction produced by various action alternatives is assessed, the most basic needs of one individual or group shall be considered only if the satisfaction of those needs does not frustrate the needs of others at the same hierarchical level.

-

4) The principle of necessary and contingent ends.

Needs are hierarchically at a more basic level if and only if their satisfaction is conceptually linked with the achievement of necessary ends like survival, health, well-being, and happiness. Needs are hierarchically at a less basic level if and only if their satisfaction is conceptually linked only with the achievement of contingent ends.

-

5) The principle of awareness.

When the need satisfaction produced by various action alternatives is assessed, the needs of individual beings shall be considered only if the beings in question can consciously anticipate, sense, or perceive, directly or indirectly, the loss involved in the frustration of those needs.

-

6) The principle of autonomy.

When the need satisfaction produced by various action alternatives is assessed, need satisfaction which is freely and informedly chosen by autonomous individuals shall be preferred to the need satisfaction of the same individuals which is not.Footnote 126

All these principles will be useful in the defense of the theory, but let me also cite the condensed version, which I meant to cover all the points:

LU The Essence of Liberal Utilitarianism

According to liberal utilitarianism, it is always right to maximize the satisfaction of needs, provided that the satisfaction of the more basic needs for survival, health, well-being and happiness is not prevented by the satisfaction of less basic needs, and provided that the basic needs of individuals and groups are not in conflict. The needs to be accounted for must be recognizable to the beings who have them, except in the case of autonomy. In the case of autonomous beings, self-determined need satisfaction is to be preferred to other types of need satisfaction.Footnote 127

Principles 1–6 explain the details, whereas LU presents the doctrine more concisely.

What we have here, then, is a theory that retains maximization and the impersonal definition of the good, albeit in a new sense, and impartiality as it appears in classical utilitarianism. The key is the revised axiology based on hierarchical needs (which I may or may not have invented).Footnote 128 I also augmented the theory with five principles for application.Footnote 129 In the first one, I specified that we should regard all decisions (including laws, policies, and the like) as individual acts. This was an attempt, successful or not, to get rid of the act versus rule controversy. The second was a confession of faith in the symmetry of acts and omissions, a fundamental utilitarian tenet that many scholars have defended, sometimes in a question-begging way, in bioethics.Footnote 130 , Footnote 131 The third was a commitment to foreseeable rather than actual consequences. If we want to make reasoned decisions, we cannot appeal to the actual outcomes of our actions because we do not know them at the time of the choice. The fourth, an attempt to circumvent a version of the repugnant conclusion, is worth reprinting here:

-

7) The principle of actual or prospective existence.

When the moral rightness of human activities is assessed, the imagined needs of nonexistent beings who will never come into existence shall not be counted.

As long as we abide by this rule, we do not have an obligation to reproduce every time we could have offsprings with tolerable lives. In time, this conviction paved way for the antinatalist view that I now apparently hold.Footnote 132 My fifth guide for applying the doctrine was “the principle of positive utilitarianism,” stating that promoting happiness and removing or alleviating suffering are both apt goals for right action. With my current antinatalist stance, I seem to have abandoned this tenet since and moved into the direction of negative utilitarianism, according to which minimizing suffering is primary.Footnote 133 Straying from some of the auxiliary rules for application is not fatal, as, to cite my original words, “these axioms are not necessarily held by all liberal utilitarians.”Footnote 134

Does liberal utilitarianism solve the problems of its classical predecessor, then? Well, yes and no. Let us begin with the repugnant conclusion. Would it be preferable, according to my theory, to have a world of billions of sentient beings whose needs are just about satisfied, or a world with millions of sentient beings whose every need is satisfied? My formulation of liberal utilitarianism squirms out of this issue instead of confronting it directly. Given the proper caveats, it is always right to satisfy the needs of those who exist, but the theory entails no obligation to create more beings with needs. It is preferable to have the needs of the many rather than the needs of the few or none satisfied, so in this sense the world with the smaller population is better. Counted one by one, the world with the larger population could have more needs satisfied than the world with the smaller population, but comparisons like this are inane. Needs and their satisfaction are not quantifiable and aggregative entities in a sense that would support such considerations. This account seems logical to me now, although the introduction of rule 7 above indicates that, in 1994, I was less sure about it.

Next up is the utility monster. Does liberal utilitarianism endure its challenge? In one way it does, in another it does not, but that is not necessarily a bad thing. Since need satisfaction is not reifiable and calculable like hedonic utility supposedly is,Footnote 135 no one sentient being can gorge it up at the expense of all others. This does not solve, however, the problem entirely. In some situations, the resources needed for the survival or health of one person are so great that hundreds of others have to forgo the satisfaction of some relatively important needs. My model cuts out—remains silent in the case of—conflicts between more basic needs, so the sacrificed needs cannot include life, health, well-being, or happiness. They can still be consequential to those experiencing them. We do not have to go further than to the cost of some drugs for rare diseases, which can drain local healthcare resources (in societies with public services), causing major inconvenience to many.Footnote 136 Should we opt for the survival of one at the expense of others? Depending on the definition of the major inconveniences, liberal utilitarianism might have to recommend it and thereby surrender to the utility monster. The question then is: Is the recommendation so clearly counterintuitive that we have to abandon the theory? Not necessarily, I would suggest, as our intuitions on cases like these are not that well defined.

Does liberal utilitarianism commit the naturalistic fallacy and does it matter? It would do that, if it defined needs as objective entities, but it should be clear by now that it does not. “More basic needs” and “less basic needs” are shorthand for values that we can specify in many ways, just bearing in mind that what the first category picks out is somehow obviously more important than what the second does. Challenge met, I believe, but the question of definition becomes crucial, and this must be born in mind.

Is liberal utilitarianism unprovable? Yes, in that, it has no geometrical proof. No, in that, we can, and must, continuously test its justification against our intuitions in various situations. Is it infeasible, in other words, does it commit us to calculations that are impossible to make? Yes, if we try to take into account everything that our actions and inactions cause. No, if we limit our attention to foreseeable consequences. This leaves questions that I will have to answer separately.Footnote 137

The issues of morality, moral integrity, justice, and self-sacrifice were focal to my development of the liberal utilitarian view, and they should not cause insurmountable problems. So what should we do in a trolley situation and, more generally, what should we think about losing the lives of some innocent people to save the lives of many others? Talking purely about head counts, my theory “solves” these cases by refusing to make the judgment and by hinting that they should be decided on other grounds. I present these grounds in the concluding chapter of the book as the methods of applied ethics.Footnote 138 Long story short, I suggest that when the more basic needs of different individuals or groups are in conflict, we have to seek solutions in further examination. This draws a line between what liberal utilitarianism can and cannot do. The further examination that I call for consists of two steps. We must first assess suggested solutions to moral and political problems for their logical consistency and conceptual coherence. This is, philosophically speaking, a straightforward matter. In the second step, we should evaluate the intuitive and emotional acceptability of the solutions that have survived the first step. This evaluation means testing views and recommendations against real-life and imaginary examples. I borrowed this idea from Jonathan Glover and recognized, like him, that it is more controversial.Footnote 139 Whose intuitions and emotions are we talking about here? The answer, presumably, is “ours,” but who are “we”? Eventually, this question, with the definition of more and less basic needs, decides whether my model holds together. These issues require careful investigation, which respects the hypothetico-deductive, aspirationally “scientific,” spirit of the endeavor.

In all the counterexamples to classical utilitarianism that involve sacrifices and self-sacrifices, basic needs are in conflict, which means that liberal utilitarianism leaves them for applied ethics to solve. Jim’s case, stated as I do above, could be an exception. If the person whom Jim is supposed to kill dies anyway by the hand of someone else in the same situation, then the choice is between letting and not letting the 19 others die. This is how utilitarians interpret the case, and this is why they often end up advising that Jim should do the deed. I do not want to make that judgment and neither does liberal utilitarianism. When I built the theory, this interpretation must have slipped my mind, as axioms 1–6 do not seem to cover it. For now, let us just assume the necessary revisions to them or a new application principle that supports the withdrawal.

Jim’s case has another reading, however, as does the Sheriff’s. What kind of a moral theory, antiutilitarians might ask, does not condemn, immediately and unequivocally, the immoral and unjust killings? For them, the cases are clear, perhaps because what Jim and the Sheriff would have to do would mean actively killing an innocent person, whereas their inaction would “only” mean letting innocent people die. Whatever the reason, it is not as clear to me as it is to them, so I am content with liberal utilitarianism leaving its solution to applied ethics. When we proceed into that territory, the absolute or near-absolute prohibition of killing can make a comeback as a hypothesis, of course. We must then study it in relevant cases to see how consistent and coherent, intuitively and emotionally acceptable it is to us. This time, we need a definition of “us,” and the conclusions will mostly be of the form, “Since we (a well-defined group) believe, think, and feel that X is the right solution, and X forms a consistent and coherent whole with our other solutions, we have good reason to believe that X is the right solution, and we can or should act upon it.”Footnote 140 Modified utilitarian views can also reappear as hypotheses in individual cases.

With these considerations, I rest my case and submit that my limited liberal form of utilitarianism can meet the challenges that sank the classical version.

What can we do with Liberal Utilitarianism?

My version of liberal utilitarianism, then, is a theory that gives guidance in moral and political decisions as long as they do not involve conflicts between the basic need satisfaction of individuals or groups. The limitation can seem paralyzing, but it is not. Hard cases make bad law, and it would be far worse to build a doctrine around particular examples involving gruesome scenes of death and mayhem. Elizabeth Anscombe, a certified antiutilitarian, summed up this feeling in 1957 in her mock suggestion on how to corrupt the youth by moral philosophy:

A third … method which I would recommend to the corrupter would be this: concentrate on examples which are … fantastic: what you ought to do if you had to move forward, and stepping with your right foot meant killing twenty-five fine young men while stepping with your left foot would kill fifty drooling old ones. (Obviously the right thing to do would be to jump and polish off the lot.)Footnote 141

Not all our important decisions involve loss of life, health, liberty, well-being, or happiness regardless of our choice, and liberal utilitarianism has, in theory, straightforward parameters for those that do not. Examples on a general level are easily stated and, at least to me, obvious.

The climate is changing; the change is, to the best of our knowledge, caused by excessive amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and further emissions aggravate the situation. Due to climate change, people and other sentient animals are dying and suffering. We could find ways to reduce and alleviate that dying and suffering, but, in many instances, this would mean the dissatisfaction of less basic needs among people in the affluent, or relatively affluent, parts of the world.Footnote 142 The most important changes would be structural and concern capital, investment, management, production, and distribution systems. Individual citizens and consumers would, however, also eventually be affected. They would not be able to buy the latest smartphone model every year or out-of-season fruit and vegetables whenever the fancy takes them. Academics should think twice before flying to conferences on the other side of the world.

The economic and political establishment argue that such sacrifices are unnecessary because sustainable development will take care of the problem.Footnote 143 “Sustainable development,” however, is little more than a new name for material growth and expansion, and its ability to remedy what it has caused—including climate change and its impacts—is questionable.Footnote 144 A much better solution would be the reduction of futile consumption, equally among all social groups, and this is what liberal utilitarianism recommends. Basic needs would be satisfied by frustrating less basic needs, a sacrifice that would be certain to leave political residue, but would still be directly justified by my principles.

This recommendation is not surprising, as I produced the entire theory in response to concerns in environmental ethics and global economy.Footnote 145 A 2020s reader could question its newsworthiness, though. Why state something that we all know and recognize? Three answers. We did not “all know and recognize” back in 1994. We do not “all know and recognize” even now. And more importantly from the theoretical viewpoint, the other doctrines in the middle of Figure 1 do not “all know and recognize.”Footnote 146 They do not spontaneously endorse downscaling on climate-related grounds. Climate action is not a primary good in Rawls’s theory, nor is it mentioned in Nussbaum’s list of important capabilities. We can add it to both lists as a separate, same-level good or capability, or we can construe meta-principles stating that climate action is a precondition for promoting primary goods and capabilities.Footnote 147 , Footnote 148 , Footnote 149 , Footnote 150 Neither solution can hide the fact that the main aim of liberal doctrines is to cater to human agency, not to the well-being of human and other sentient beings. This makes them more amenable to business and technology solutions, “sustainable development,” than to reductions in production and consumption. Habermasian discourse ethics may, in real-life negotiations, end up in the same camp. No matter how much we emphasize the importance of hearing everybody’s voice in decisionmaking,Footnote 151 the voices that rise above others in any current discussion are those of technology and business.Footnote 152

None of this is a criticism of Rawls, Nussbaum, and Habermas’s theories as an answer to something. That something is, as I see it, the “applied ethics step” of moral and political deliberations. Once we have settled (and liberal utilitarianism tells why) that we do not allow the frustration of more basic needs, by act or omission, for the sake of less basic need satisfaction, we can proceed to more intricate accounts. These will specify how we can promote the overall goal justly and tolerably. The verdict will eventually turn on the intuitive and emotional acceptability of the normative recommendations, as philosophers can, I expect, provide coherent and consistent accounts of all major candidates.

Let me explain why I want the liberal utilitarian credo to precede other considerations. It is all to do with our treatment of nonhuman animals. As I already stated, my starting point in devising liberal utilitarianism was environmental ethics. This emphasis was, however, not based on the survival of the planet (it will survive for a time, anyway, and then meet its demise), biodiversity as such (as opposed to its huge instrumental value to sentient beings), or even the survival of humanity (compare what I said about the planet). The prompt was the frustration of the basic needs of nonhuman and human sentient beings alike by human activities all around the world. I wanted to have a foundation that makes removing this frustration our priority, and liberal utilitarianism defines how. None of the other theories of justice in the center of Figure 1 does this. Nonhuman animals do not feature much in the works of Habermas and Rawls, and although Nussbaum expresses an interest in them,Footnote 153 her focus remains on humans and their capabilities. In contrast, liberal utilitarianism addresses the matter head on. Which could be its undoing.

I will now boldly break the fourth wall and address my commentators directly. My following recommendations, based on liberal utilitarianism without any mediation or further elaboration, may well be unacceptable to some, many, or all but myself. If they are, please speak up! Here goes.

This is what liberal utilitarianism has to say about the plight of nonhuman animals.Footnote 154 , Footnote 155 , Footnote 156 , Footnote 157 , Footnote 158 , Footnote 159 , Footnote 160 , Footnote 161 , Footnote 162 (1) Industrial animal farming, including fur farming, is wrong. It frustrates the basic need satisfaction of sentient nonhuman beings for the sake of the less basic need satisfaction of human meat eaters, egg eaters, milk drinkers, and fur clothe users. (2) Animal experimentation in science is prima facie wrong. If it serves the more basic needs of human animals as well as frustrates the more basic needs of nonhuman ones, we must assess it separately. The same applies to situations in which it does not affect the more basic needs of nonhuman animals to begin with. The burden of proof, however, is on those who defend the practice. (3) Animal testing outside science (cosmetics, etc.) is wrong. I cannot imagine situations in which it would involve the basic needs of humans. (4) Interfering harmfully with the wildlife habitats of nonhuman persons is prima facie wrong. The beings that I am talking about here include at least chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, bonobos, whales, and other cetaceans.Footnote 163 If the interference does not frustrate their basic needs or if it promotes the basic needs of human or other animals, we need a separate assessment, with the burden of proof on those who defend the action. (5) Interfering harmfully with the wildlife habitats of nonhuman sentient beings who are not persons is also prima facie wrong, and the same specifications apply. (6) Using nonhuman animals in entertainment, including zoos, circuses, and the film industry, is wrong. Again, I cannot see how this could serve the basic needs of other human or nonhuman animals. (7) Keeping animals as pets is prima facie wrong. (8) Using service animals is prima facie wrong.

Some comments are in order. In the cases in which I do not use the prima facie caveat, I believe that the suffering of nonhuman animals for the sake of human pleasure is self-evident, and that the avoidance of suffering is a more basic need than the achievement of pleasure. In a fuller development of the view, I would have to systematize this taxonomy further to get rid of the ad hoc impression that I may create here.Footnote 164 The easiest way to challenge my verdict in cases (1)–(8) would be to say that human beings are different from nonhuman beings and have higher value, status, and worth. As an external criticism, this makes sense to all those who hold that opinion. As an internal matter, it is not a criticism at all, since the need-based model that I rely on does not recognize the distinction. In Jeremy Bentham’s words, “the question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”Footnote 165

In the cases in which I do use the prima facie caveat, we can find much more wiggle room. I use the expression in the sense, “if not proven otherwise,” and invite anyone who disagrees with my findings to prove otherwise. You can do this universally or case by case. A universal objection could state something like, “Pet keeping is right, because it gives people comfort and pleasure and offers pets a good life.” This protest is unlikely to survive scrutiny. It is all too easy to show that not all pets have a good life.Footnote 166 A more particular objection would be, “Pet keeping is right in my case, because it gives me comfort and pleasure and offers my pet a good life.” This appeal is, if the claims can be empirically substantiated, more likely to succeed. At least in isolation, it can survive the needs challenge, although it may fall prey to other arguments, those founded on animal rights included.Footnote 167 In practice, this would mean, minimally and to start with, licensing pet keeping and pet keepers as well as pets. If you want a companion cat, dog, or gold fish, the magistrates must first give you, on your well-argued request, a permission for the arrangement.

Another matter on which liberal utilitarianism has a clearer theoretical view than its competitors is cross-border international aid. I have detailed in a previous study the case of disability as a test of justice on a global scale.Footnote 168 The specific disability in the study was river blindness caused by preventable factors.Footnote 169 The analysis showed that most other theories of justice and morality (see Figure 1) fail to recognize, or fail to recognize automatically, the obligation of more affluent regions to offer assistance to countries affected by the epidemic.Footnote 170 Libertarianism rejects the obligation forthwith, appealing to the immunity of private property. Positional (communitarian and care) responses are contingent on the context. They can endorse the duty in some instances but reject it in others, depending on the involvement of parties with whom they identify or have special relationships. Rawlsian scholars disagree among themselves, some defending cosmopolitanism and others rejecting it. Capabilities theorists, classical utilitarians, and socialists can recognize the duty to aid, if the circumstances are appropriate for it. Liberal utilitarianism offers the clearest verdict. It is our prima facie obligation to provide international aid, when our own more basic needs are not at stake. Two issues arise here, however, and I will deal with them separately.

First, if we assume such international as well as national duties, does it mean that we just have to keep giving until we do not have proper, flourishing lives ourselves? Anthony Quinton, a utilitarian himself, has expressed this sentiment succinctly:

Ordinary utilitarianism, along with some other moral theories and a lot of religiously inspired moral stock responses, is utopianly altruistic. It implies that in every situation in which action is possible one should choose that possibility which augments the general welfare. That would rule out as morally wrong not only harmless self-indulgences like sitting in the sun, reading for pleasure and non-strenuous walks in the countryside (since in each case one could be working or begging for Oxfam), it would also override most of the altruistic things we do for people to whom we are bound by ties of affection.Footnote 171

The distinction that liberal utilitarianism draws between more and less basic needs cancels this concern. We can define on a general level what sacrifices we ought to make to benefit strangers in other countries and in our own and how. Better yet, we can define the division in individual cases. If people in affluent regions have to postpone the purchase of a new smartphone for a month to secure millions of people in Africa against river blindness, the decision to help is a no-brainer. The stage at which decisions cease to be so easy is when we list all the other candidates for help. This should not put us off from trying. Yes, the problem is wide and systemic. Yes, we must study facts in innumerable areas to make the proper judgments. We must define the limits of our capacity to offer aid against the possibility of eventually losing what is meaningful in our own lives. The latest-model smartphone now rather than next year is not, however, a good contender for a more basic need. Assuming the liberal utilitarian stance would make this starting point clear, whatever the results of further analyses.

Secondly, is talking about climate change, industrial food production, and international aid bioethics? In one sense, it is, and in another, it is not. Looking at the field today, the journals, publications, conference topics, and generally areas of interest among those who call themselves bioethicists, the answer is mostly negative. It seems that we should concentrate on the availability of sperm in fertility clinics, or the latest scandal in genetics, or in the keeping or not keeping alive someone with very low brain function. In the words of one author, we have become “demagogues, fire fighters, and window-dressers.”Footnote 172 Looking at the field back then, in the 1980s and 1990s, however, we see a different picture. The titles of seminal books included epithets like “practical ethics,”Footnote 173 “biomedical ethics,”Footnote 174 “medical ethics,”Footnote 175 “philosophical medical ethics,”Footnote 176 , Footnote 177 and “healthcare ethics,”Footnote 178 and in specific cases “research ethics”Footnote 179 and “nursing ethics.”Footnote 180 The fledgling discipline acknowledged many branches with different agendas and methodologies, and the similarly nascent “environmental ethics” still had strong links with some of these, under the umbrella term “applied ethics.” Then, during the 1990s, the identity-craving, newly named “bioethics” hijacked the entire field, the fertile differences between the subdisciplines partly evaporated, and wider considerations drifted into politics, political philosophy, and environmental ethics, now an independent area of study. During this millennium, the field of bioethics was then, perhaps irretrievably, carnivalized by sensation-seekers (like me, I do not want to implicate other, more notable colleagues—they know who they are)Footnote 181 , Footnote 182 , Footnote 183 , Footnote 184 , Footnote 185 , Footnote 186 and commercialized by serious scholars who introduced the term “clinical bioethics” in order to make ethicists the followers of psychologists and the clergy in hospital life as moral experts.Footnote 187

In my current academic position at a business school, I can see more clearly than before the way bioethics is going. It is not necessarily an encouraging sight. Instead of being the guardians of all life,Footnote 188 or advocates of a new regime for our world,Footnote 189 bioethicists are in real danger of becoming, like “business ethicists” before them, enablers of global capitalism (by omission, by not studying the wider scene) or apologists of ineffective and uncaring health systems (by washing their dirty laundry). Some approaches, notably feminist and postcolonial, have kept their course, though, and by reintroducing my liberal utilitarian model, I would like to lure “mainstream” bioethicists, especially philosophical ones, to follow suit. Concentrate on big themes, if you can. If you have to focus on smaller matters, start from the liberal utilitarian premise, and if it does not work, try the model again at the applied ethics level by making auxiliary assumptions. Then, if the assumptions made begin to appear unintuitive or absurd, retreat in good order and try using other ethical models, constantly keeping in mind the method of applied ethics with its logical, conceptual, intuitive, and emotional steps.

What kind of “smaller matters” do I mean and what kind of auxiliary assumptions could be helpful? Let me present briefly three recent medical and related concerns that have drawn ethical attention. First, some people want to amputate their healthy body parts, most commonly legs, and ethicists have studied whether surgeons should comply.Footnote 190 Floris Tomasini has presented an insightful liberal utilitarian analysis of the practice.Footnote 191 His conclusion is that my theory would possibly allow the removal of one leg but not both because the self-demand amputee’s need to correct their identity is greater than their need to have both legs, whereas the need to have at least one leg overrides the identity need.Footnote 192 Secondly, two bioethicists recently suggested that mothers, if their situation has drastically changed since the onset of the pregnancy, should be permitted to have their babies killed rather than given to adoption.Footnote 193 My own reaction to this “after-birth-abortion” proposal and its inevitable aftermathFootnote 194 was different,Footnote 195 , Footnote 196 but an analysis along the lines Tomasini sketches would, I suppose, be possible here. If we ignore the infant’s need to survive,Footnote 197 the task would be to weigh the mother’s needs against the needs of those aggravated by the policy. Thirdly, some Japanese men apparently find comfort in having anime hologram companions,Footnote 198 and some bioethicists are interested in the phenomenon’s moral and social dimensions.Footnote 199 Again, a liberal utilitarian analysis would be possible. What needs do these holograms satisfy and what other needs (and whose?) should we take into account?

Concluding Thoughts

My commentators may wish to evaluate further the three cases I just presented—or others like them—in a liberal utilitarian or related framework. Apart from the general observation that such evaluations are indeed possible, I would not know myself how to begin a detailed analysis on this level. The cases are so (in want of a better term) delicate that their cold-blooded liberal utilitarian scrutiny seems slightly preposterous, as properly noted by Tomasini in the self-demand amputee instance.Footnote 200 On a more general level, the situation might look more promising. I could go back to the original Enlightenment spirit of the theory, detected by an earlier commentator,Footnote 201 but that would come with a price. The enlightened utilitarian would probably say that balanced, sane citizens of well-run societies would not ask medical doctors to cut off their legs or kill their babies, and that self-delusional relationships with hentai holograms, even if freely and autonomously entered into, are unsavory. The solution, accordingly, would be to provide good education, emotional support in childhood, and comprehensive mental health services for all. Although some may find this recommendation reasonable, it has two problems. The first, at least when it comes to self-demand amputees and hologram companion lovers, is that they already exist, so we still have to address the issue on all its levels. The second is that moving to the “Enlightenment direction,” from left to right in Figure 1, may mean ignoring legitimate community, identity, recognition, and care concerns. For a proposed compromise, this would be dubious, and it would leave considerable moral and political residue by pathologizing differences.Footnote 202

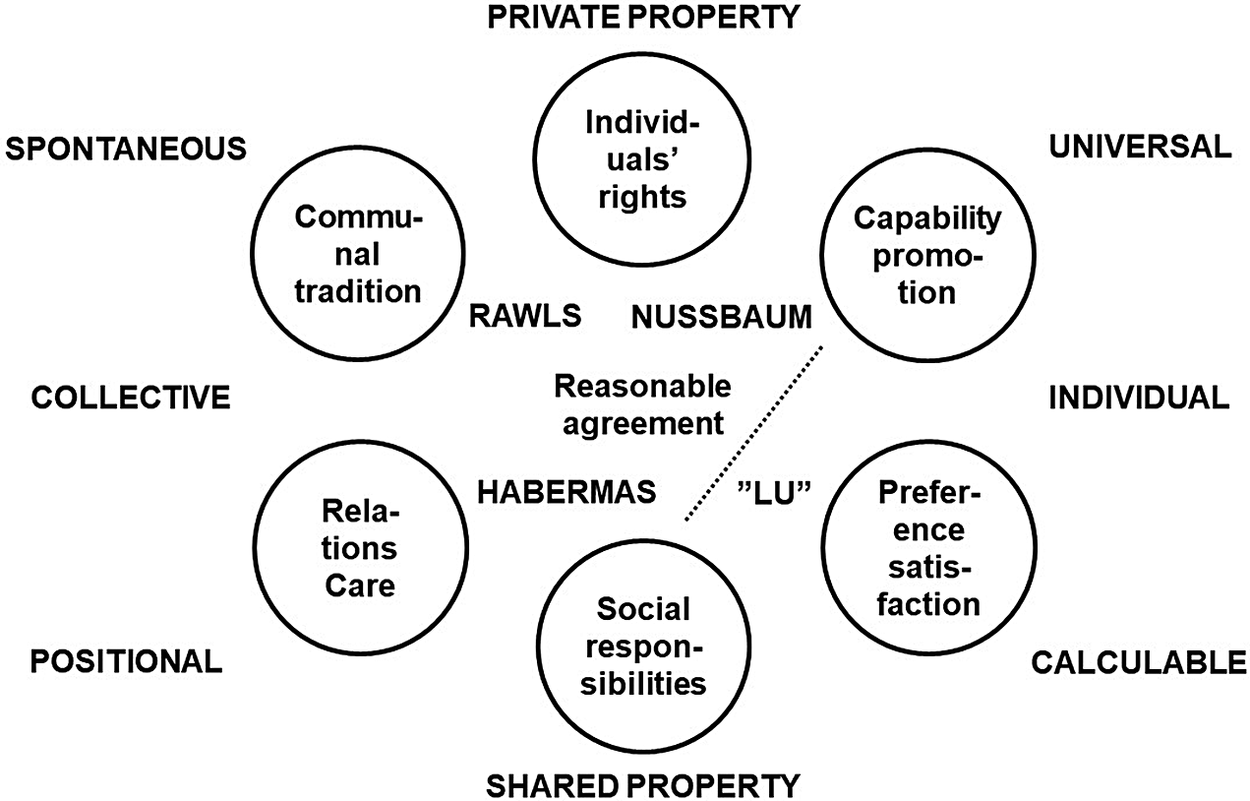

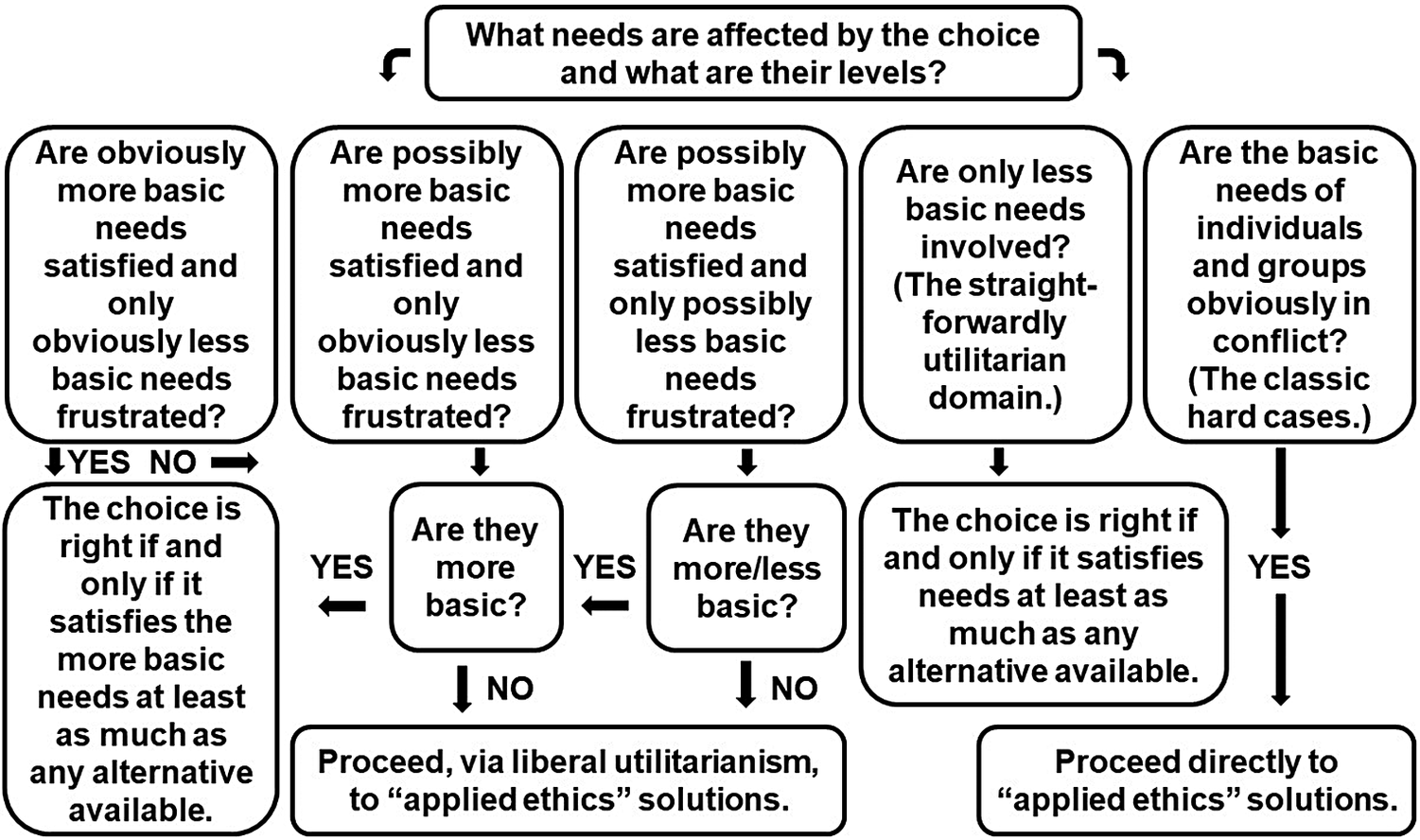

Due to the difficulties of a full Enlightenment interpretation, I would appeal to the tiered structure of liberal utilitarianism one final time. We first identify the needs that we affect by our decisions and assess their levels. Are some of them obviously more or less basic? Are some of them possibly, although not obviously, more or less basic? Does our choice satisfy needs that are more basic and frustrate only needs that are less basic? If it does, then it could be the right one. Does our choice involve only less basic needs? Then we can settle the matter by a traditional utilitarian comparison. Does our choice engage the more basic needs of two or more individuals or groups? Then abandon the utilitarian solution and start finding solutions in other theories by the methods of applied ethics. Figure 2 presents the alternatives in schematic form.

Figure 2. Decisionmaking according to liberal utilitarianism.

Figure 2 may give the impression that we can easily solve nearly everything by liberal utilitarianism and that only the classic trolley-, Jim-, and sheriff-type situations elude it. Almost the opposite is, in fact, true. Stripping away the extra color that philosophers have added to their counterexamples, basic needs are in conflict in numerous public decisions. If the local authority decides to build the new state-of-the-art health station to the northern part of its jurisdiction, it may leave people in the southern part without the best emergency services, thereby letting some of them die or suffer. Liberal utilitarianism cannot solve the issue. Further cases surface, when we start telling people what sacrifices they would have to make in the name of climate work, animal welfare, and international aid. In all these cases, I believe that a sensible definition of more and less basic needs disentangles the situation, despite the disagreement of fossil fuel producers, industrial animal farmers, and nationalist egoists. A lot of conceptual work is required, though, in these cases and others, to reach acceptable clarifications.

Why do I want to advocate liberal utilitarianism, then? If we do most of the work in the conceptual clarification of values and in the application of nonutilitarian moral and political doctrines, what is the point of insisting on the liberal utilitarian starting point? My response relies on the importance of ends over means. In the majority of cases, we may find the practical answers to our questions in value analyses and appeals to rights, duties, virtues, care, identities, recognition, capabilities, and the many other normative building blocks of theories of justice and morality. Thinking, however, that we have to protect a right for its own sake, or live by a virtue just because it exists, would be a mistake. That would, I believe, be pursuing the means rather than the ends. The ends that I have named here are the satisfaction of the more basic needs of sentient beings with some side rules, the satisfaction of the less basic needs of sentient beings under certain circumstances, and the logical consistency, conceptual coherence, intuitive acceptability, and emotional acceptability of decisions when the basic needs of individuals or groups are in conflict.

My commentators may wish to challenge me on this. They are welcome to do so. They may also wish to engage in liberal utilitarian assessments of policies or practices to show its inadequacies on one or more levels. They are welcome to do that, too. Meanwhile, I stand by my theory until proven otherwise. I have reassessed my relationship with utilitarianism before, and more or less renounced the doctrine.Footnote 203 I will probably continue the reassessment, but for now, my interim conclusion is that I may be a liberal utilitarian, after all. For this revelation, and I am sure that the world is shaking for it, I needed to go back to the roots and to remember my original starting point in environmental, nonhuman-animal, and international aid issues.