A curious sketch on the verso of Dunhuang manuscript Pelliot chinois 2598, as given in Figure 1, features three animals previously misidentified as “yaks”.Footnote 1 While at first glance very similar to a yak, I would like to argue for these three creatures to be identified as a specific type of dog. Through textual and artistic comparisons, I would like to assert that these are in fact representative of the same kind of dog which was prized in the Tang court. These small dogs, recorded as being introduced from abroad, marked a distinct change in accepted roles for dogs, being valued for their size, intelligence, and companionship, as opposed to skills related to hunting or guarding.Footnote 2 I therefore hope to prove that knowledge of these diminutive dogs existed in Dunhuang, as shown in this manuscript, and explore what conclusions and hypotheses may be drawn from this assertion.

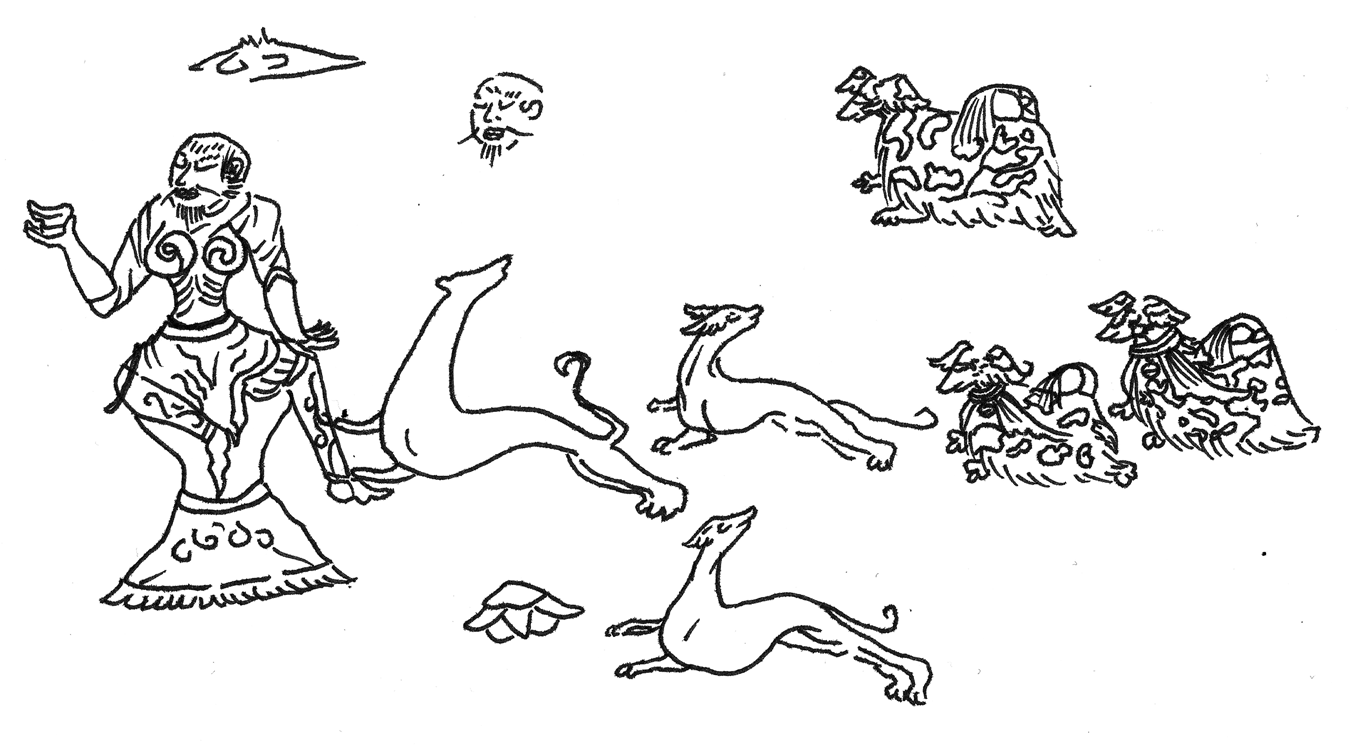

Figure 1. A line drawing completed by the author of the sketches on the verso of Pelliot chinois 2598 (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris). The original sketches were completed in ink, and the patches on the three animals on the far right, as well as the entire form of the left-most hound, were inked in.

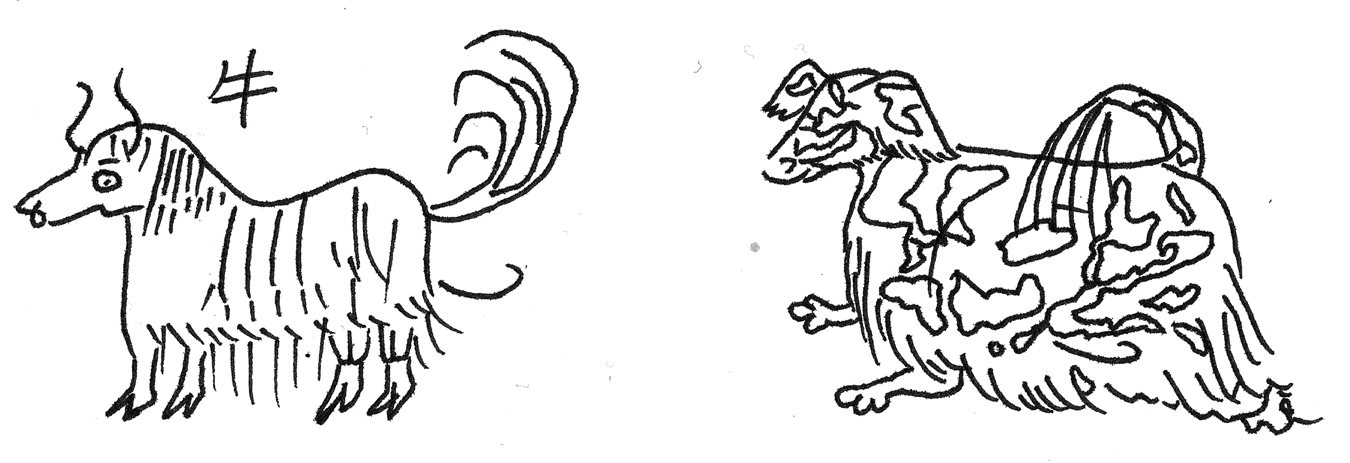

Before looking at the manuscript as a whole or the wider context of these drawings, the identification of the three animals on the far right as yaks must first be brought into question. It should be immediately obvious that, unlike yaks, these animals clearly have paws instead of hooves. A yak or ox and a dog are illustrated on the verso of a further Dunhuang manuscript, Pelliot chinois 2622, and the difference between hooves and paws is made clear both between these two figures and between the “yaks” in both manuscripts, as shown in Figure 2.Footnote 3

Figure 2. Line drawings completed by the author comparing the yak or ox from the verso of Pelliot chinois 2622 (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris) with one “yak” from the verso of Pelliot chinois 2598. The patches seen on the “yak” were originally inked in.

In order to clarify the exact identity of these three animals, the central group of dogs should first be identified. Clearly distinct in their presentation from those on the far right, these three dogs will be termed as hounds throughout. As this is a drawing, the scale of these animals both in real terms and in relation to each other is not clear. Indeed, the relative scale may not be reflective of reality at all. However, it is likely that these three hounds were actually reasonably large animals due to the striking parallels between them and Tang figurines of hunting hounds such as the greyhound or saluki.

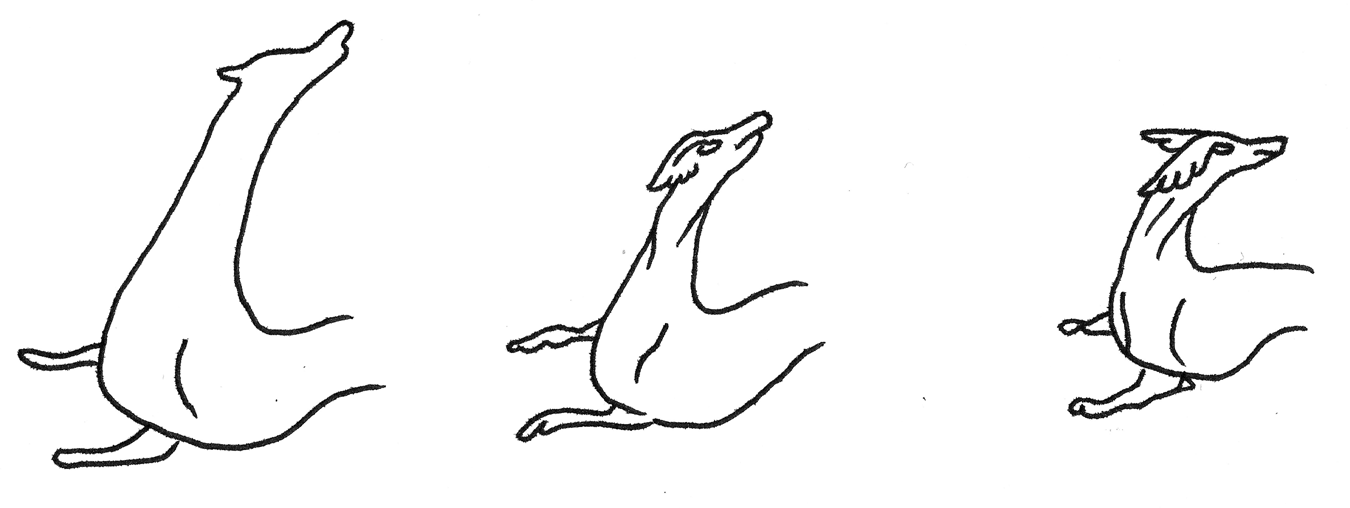

Ascribing exact breeds of modern dog onto ancient representations is flawed in many ways – dog breeds may not yet have developed into the form recognized today and may not have been as separate from each other as modern breeding programmes dictate. However, dogs with the distinctive ribcage of the broad greyhound category are evident even in Han 漢 (206 bc–220 ce) bas-reliefs, although it is not clear whether these animals were imported from the greyhound's original territory of Egypt or were a parallel strain of Chinese greyhound.Footnote 4 By the Tang period, a further variation of this slim hunting hound can be seen in tomb art – the saluki, which is identified in Chinese art by its long-haired ears in place of the short ears of the greyhound.Footnote 5 The same distinctive ribcage and hollow stomach can also be seen in all three hounds in this manuscript, however only the two dogs to the right have long-haired saluki ears while the inked-in dog has greyhound-like ears, as is made clear in Figure 3.Footnote 6

Figure 3. Line drawings completed by the author comparing the ears of the three hounds from the verso of Pelliot chinois 2598. The first has greyhound-like ears, while the other two have long-haired saluki ears. The greyhound was originally washed with ink. The placement, but not the size, of these hounds has been changed so as to better compare their respective ear shapes, and the original arrangement of these hounds can be seen in Figure 1.

The particular pose of fluid motion in this manuscript can also be seen in Han murals of greyhounds in hunting scenes.Footnote 7 A standing saluki in a Tang mural displays a similar fluidity in its posing, and the overall similarities between greyhounds and salukis in tomb figurines and murals, as well as in this manuscript, suggest that both dog distinctions were used in hunting interchangeably.Footnote 8

With this identification in mind, it is possible to contrast these depictions with the second group of dogs, the “yaks”. These three animals clearly bear no similarities to the elongated, fluid poses of the nearby hunting hounds and have neither a distinct ribcage nor a hollow stomach. Should these be working dogs, then they may be engaged in the other major task related to dogs: guarding. Eastern Han 東漢 (25–220 ce) tombs are replete with ceramic representations of guard dogs that may be compared with these three “yaks”.Footnote 9 These ceramic tomb figurines usually depict dogs snarling or barking in the act of guarding, and nearly all known examples wear harnesses, implying that they were tethered. These harnesses also indicate that the dogs were of a large size and have even been associated with the mastiff category.Footnote 10 Eastern Han ceramic figures of guard dogs can also have similar folded ears to those in this manuscript.Footnote 11 However, the “yaks” lack the two defining features of stereotyped depictions of guard dogs in that they are not wearing harnesses and are not captured in a moment of warning or barking. Instead, two of these “yaks” are drawn wearing dangling ribbons with a bell, something not seen in depictions of guard dogs or indeed any pre-Tang dog.Footnote 12

With no pre-Tang depictions of lapdogs, i.e. small dogs kept purely for pleasure and companionship, Tang official and unofficial histories, poetry, and paintings attest to the sudden arrival of small, intelligent dogs from abroad in the early Tang period.Footnote 13 Firstly, Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 (Old Book of Tang), Cefu yuangui 册府元龜 (Outstanding Models from the Storehouse of Literature), and Tongdian 通典 (Compendium of Institutions) all attest to the gifting of two diminutive dogs in 624 to Emperor Gaozu 高祖 (566–635, r. 618–626) by Gaochang 高昌 (Turfan), with the dogs apparently originating from Fulin 拂菻 (Byzantium).Footnote 14 A further tale in Youyang zazu 酉陽雜俎 (Miscellaneous Morsels from the Youyang Cave) tells of a dog from Kangguo 康國 (Samarkand) belonging to Yang Guifei 楊貴妃 (719–756), terming the dog wo 猧 (dwarf-dog).Footnote 15 It is not yet clear whether the term wo refers to small dogs, lapdogs in a general sense, or a specific breed of lapdog. It is my belief that the answer lies somewhere between the latter two definitions, and as such I will henceforth use the terms wo and lapdog interchangeably.

Their marked intelligence and diminutive size, as well as potential overlaps with other exotic animals like parrots, meant that these imported small dogs were depicted alongside court women as beloved lapdogs in the late Tang period. The most famous example of this is Zanhua shinü tu 簪花仕女图 (Ladies Wearing Flowers in Their Hair) attributed to Zhou Fang 周昉 (c. 730–800), in which the two diminutive dogs are similar to those in Pelliot chinois 2598 given their long hair, colouration, and hanging ribbons, as is shown in Figure 4.Footnote 16

Figure 4. Line drawings completed by the author comparing the two “yaks” which wear ribbons with bells from the verso of Pelliot chinois 2598 with the two dogs from Zanhua shinü tu 簪花仕女图 (Ladies Wearing Flowers in Their Hair), a piece completed in ink and colour on silk which was once a series of screen inserts then reassembled into a handscroll (Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang). The two dogs from this painting were originally coloured with light pink ribbons and brown and white fur. They are drawn side by side here but are separated in the original composition.

The use of ribbons with bells is also associated with lapdogs in poetry in the Northern Song 北宋 (960–1126) period, with a dog named Taohua 桃花 (Peach-blossom) being described as such:

Clearly, the wearing of long ribbons and bells is synonymous with these diminutive wo in the art and literature of the Tang and Northern Song periods. So too do the recorded names of various wo suggest the patterned colouration of fur as seen in these three “yaks”. This includes Huazi 花子 (Flowery or Patterned), Huaque 花鵲 (Flower-magpie or Patterned-magpie), and Taohua 桃花 (Peach-blossom), given that hua 花 can mean both “flower” and “dappled” or “patterned”.Footnote 18

Thus, these three “yaks” should instead be identified as wo due to their physical appearance, colouration, and decoration. As previously discussed, the scale between these dogs and the nearby group of salukis and a greyhound does not necessarily mean that such dogs were of a similar scale – indeed, the depiction of wo in Zanhua shinü tu highlights their small size in relation to court women, as do further depictions of lapdogs alongside women in ceramics.Footnote 19 Thus, if these three dogs may be said to represent the same diminutive, decorated lapdogs prized by court women in the Tang and Northern Song periods, what can we learn from their being depicted in Dunhuang?

First, the context of the manuscript itself must be taken into account. The recto features one juan of Xinji wenci jiujing chao 新集文詞九經鈔 (Newly Compiled Selections from the Nine Classics) copied by Yin Xianjun 陰賢君 with some of the beginning missing. This text is then followed by a few exercises including an improvised poem and the beginning of a letter.Footnote 20 However, the poem and letter are of distinctly different hands to that of the copyist Yin Xianjun, implying that this manuscript was used by several people after Yin Xianjun's copying was completed. This seems to be in order of Yin Xianjun, the poet, and then the letter-writer, given the placement of each respective text. Had the order of ownership or use been different, we would expect the arrangement of writing to reflect this.

From the recto of Pelliot chinois 2598, it is already clear that this manuscript has been used by several people after Yin Xianjun copied one juan of Xinji wenci jiujing chao. The verso contains further fragments of texts, these drawings, an 873 colophon, and a colophon attributing the overleaf copying to Yin Xianjun in 883. Victor H. Mair gives these as being in “poor to very poor hands”.Footnote 21 The verso 883 colophon can be transcribed as follows:

中和參四月十七日未侍 (→時) 書了。 陰賢君書。

In the third year of the Zhonghe (881–885) reign period, on the seventeenth day of the fourth month at the hour of wei, [this] was written. Yin Xianjun wrote [this].Footnote 22

The writing of this colophon is certainly of an inferior hand to Yin Xianjun's on the recto and therefore cannot be assumed to have been written by Yin Xianjun himself. This leaves the exact dating of his copying uncertain.

Other texts on the verso include the beginnings of association circulars, repetition of characters seemingly for practice, and writing exercises in various hands. While the beginning of the text is missing on the recto of Pelliot chinois 2598, this is perhaps preserved on the rectos of Pelliot chinois 2557 followed more definitively by Pelliot chinois 3621 as these correlate with the missing text and are written in the same hand.Footnote 23 These three pieces may then originally have been one manuscript – an assumption furthered by the fact that the verso of Pelliot chinois 3621 contains similar writing exercises and a partially completed drawing.Footnote 24 Given the stark change in the quality of writing between the recto and verso in both Pelliot chinois 2598 and 3621, these drawings may not have been done by Yin Xianjun or in 883. Who drew these, when they were drawn, and for what purpose therefore remains unclear. However, given the pragmatic nature of the various texts on the verso and the instructive nature of the text copied on the recto, this manuscript was probably the property of several students, perhaps lay students, and connected with an educational environment.Footnote 25 As the copying of didactic texts by students with fragments of association circulars written on the verso is a particular feature of Guiyijun 歸義軍 (848–1036) Dunhuang manuscripts, this drawing can be considered to be part of a Dunhuang manuscript used by students from at least 873 until at least 883.

Second, the drawing itself may also provide further information about why these wo were depicted. The drawing of both groups of dogs is accompanied by a seated figure on a pedestal as well as an incomplete drawing of a head and two other items above and to the lower left of this figure. The seated figure is an armour-clad male with an exaggerated breastplate and a sword at his belt. He is holding a cup aloft in one hand and seems to be seated on a pedestal placed on an ornate, fringed rug. The incomplete head seems to match that of the seated figure and so may have been a practice-run, further copy, or a later copy in another hand.

The seated figure may be compared with Zoroastrian and Buddhist images from the Dunhuang corpus in order to give further context to this drawing. The holding of a cup bears strong similarity to the iconography of Pelliot chinois 4518 no. 24, an ink painting which is often referred to as the Sogdian Deities sketch. In this manuscript, two female figures sit facing each other, with one holding a fluted cup or bowl in one hand and a small dog aloft on a dish in the other, while the opposite figure is seated on a large wolf-like animal. There has been much debate about which deities these female figures may represent, however the holding of a cup, seated position, and the presence of large and small dogs seem to parallel the broad themes of the drawing on Pelliot chinois 2598.Footnote 26

On the other hand, the holding of glass vessels and other such items can be associated with Buddhist deities, such as in painted banners of bodhisattvas.Footnote 27 The figure in the cited banner from the British Museum bears more masculine features, such as facial hair, as well as a similar slender waist to that seen in Pelliot chinois 2598. Here, the glass-bowl not only represents one of the seven treasures of Buddhism but also alludes to the importation of glass into China from the Iranian world.Footnote 28

Hunting hounds in particular are also linked with Buddhist imagery through the genre of soushan tu 搜山圖 (Picture of a Mountain Search) paintings.Footnote 29 These may once have depicted symbolic hunts around Buddhist temples in Gaochang which were thought to remove harms, as described by Wang Yande 王延德 (939–1006) on his return to the Song court in 984.Footnote 30 Indeed, one such non-extant painting was given to Emperor Taizong 太宗 (939–997, r. 976–997) in 976.Footnote 31 A possibly similar example is seen in a mural from the north wall of the central chamber of Bezeklik Cave 20 in the tenth century.Footnote 32 The mural in question depicts a slender hound biting a demon in the lower register of the scene while an armoured, armed figure marked by a halo stands in the upper register.

While various tianwang 天王 (Heavenly Kings) are depicted in this cave, many seem to correspond with the iconography of Bishamen Tianwang 毘沙門天王 (Vaiśravaṇa) of the North, who is likely the main figure of the aforementioned mural.Footnote 33 The depiction of hunting hounds is also described with regard to non-extant images of Vaiśravaṇa, as can be seen in Yizhou minghua lu 益州名畫錄 (Record of Famous Painters of Yizhou). This text was compiled by Huang Xiufu 黃休復 (dates unknown) in 1006 and gives his critique of several Tang and Song painters from the region, with the following excerpt describing a potential soushan tu scene painted by Sun Wei 孫位 (fl. 885–888):

倣潤州高座寺張僧繇戰勝一堵。兩寺天王、部眾。人鬼相雜,矛戟鼓吹,縱橫馳突,交加戛擊,欲有聲響。鷹犬之類,皆三五筆而成,弓弦斧柄之屬,並掇筆而描。Footnote 34

The monk Zhang of the Gaozuo temple in Fangrun prefecture commissioned [Sun Wei to paint] a mural of a battle scene. [He painted] the Heavenly King and Buddhist disciples of the two temples. People and demons were mixed up together bearing spears and halberds, drums and flutes, and charging horizontally and vertically. Their clashes and blows were on the verge of echoing sound. All those of the hawk and hound variety were completed in a few brush-strokes. All those of the bow-string and axe-handle type were depicted by [simply] picking up the brush.

Although Sun Wei's paintings of other Heavenly Kings designate their associated direction, as the content of the painting clearly matches with the soushan tu genre, we can surmise that this was a depiction of Vaiśravaṇa and was perhaps implicit enough not to warrant the added specification of his direction.Footnote 35

Further depictions of this figure in Dunhuang materials attest to a standardized iconography in which he holds a stupa in his left hand and a standard in his right while wearing armour with a long sword at his belt.Footnote 36 This can be seen in a standing image of Vaiśravaṇa from a 947 wood-block print, as well as in a seated image from the face of a relic box from the Famen temple 法門寺.Footnote 37 The seated position depicted on the relic box is very similar to that seen in this manuscript; however, the items held do not match.Footnote 38

Further paintings show Vaiśravaṇa holding the stupa and standard, sometimes a sword or halberd, in the opposite hands, as seen in a ninth-century painting from Dunhuang, which could then loosely parallel the depiction in Pelliot chinois 2598.Footnote 39 Nevertheless, Vaiśravaṇa is usually accompanied either by a subjugated demon under his feet or a child in the background – the latter recalling a Khotanese legend associated with Vaiśravaṇa, their patron deity.Footnote 40 The seated figure here, while armoured with a long sword tied to his belt and potentially holding a stupa aloft in his right hand, does not have a standard in the other hand and is sat on a rug instead of atop a subjugated demon. Despite the fact that hunting hounds are linked with Vaiśravaṇa, there is incorrect or missing iconography in this depiction, which may be because this figure was drawn from memory or because the student was unfamiliar with the exact iconography needed. Of course, this may not be Vaiśravaṇa at all. A final possibility is that this may be an artist's sketch rather than the work of a student.

Following from Sarah Fraser's analysis of artists’ sketches at Dunhuang, this may then be a preparatory drawing for a mural, serving as a reminder for “easily forgotten features and unusual characteristics”, or a practice sketch, which were largely “random details and repetitions of the same parts”.Footnote 41

If this sketch were a preparatory drawing for a mural then we may see traces of similar canine iconography in extant murals from the Mogao caves. However, there are very few instances of dogs among these murals and none which correspond even remotely with the three “yaks”. One slender, red-furred dog with a long curled tail can be seen on the western side of the southern wall in Cave 459 and dates to the late Tang period.Footnote 42 Being part of a larger scene on the anti-Buddhist acts of hunting and butchering animals based on Lengjia jingbian 楞伽經變 (Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra), this dog must then be a hunting hound or at the very least a dog usually related with hunting. Its slender shape and overall fluidity is very similar to depictions of greyhounds and salukis discussed herein, although the shape of its ears is somewhat unclear. A further slender dog with grey and white colouration and distinct greyhound ears can also be seen in Cave 85.Footnote 43 Positioned in a similar crouched pose, this dog has its head lowered to lie underneath a table. Since both dogs feature in larger scenes relating to the evils of hunting and butchering, their crouched posture can be interpreted as them waiting for the head of the butchered animal to fall. This reiterates the clear association between greyhounds and salukis and acts of hunting in Chinese art. However, given the fact that their crouched position is so dissimilar to that seen in Pelliot chinois 2598 and that these dogs show no other similarities to the sketch in question, there is as yet no local mural that can be definitively linked with this manuscript.

Furthermore, it is the randomness of the figures in the drawing on Pelliot chinois 2598 that suggests it is an artist's sketch rather than a preparatory drawing for a mural, as Fraser summarizes:

In those [wall painting sketches], while space was collapsed, each figure had some thematic relation to the other figures. In these practice sketches there is little or no connection between [the subjects], other than an artist may have been working on paintings with these assorted topics at the same time. In the random, abbreviated mural sketches the drawing is loose and often very abbreviated; here many of the sketches are meticulously rendered […]Footnote 44

We can see that the drawings here are relatively complete and not “abbreviated”. Furthermore, artists’ sketches were often drawn on seemingly unrelated manuscripts, manuscripts Fraser takes as having been discarded. This seems to be the case with Pelliot chinois 2002 whose verso drawings bear no relation to the fire-damaged Wushang jinxuan shangmiao daode xuanjing 無上金玄上妙道德玄經 Daoist text of the recto or to the context of the manuscript, nor do the drawings relate to each other.Footnote 45

If the sketch on the verso of Pelliot chinois 2598 is thus a practice sketch as defined by Fraser then, much like the example of Pelliot chinois 2002, there are no intended parallels between the deity, hunting hounds, and the three wo. This assertion is also supported by the fact that, while there are some representations of Buddhist and Zoroastrian deities with such hounds, there are no known representations of wo alongside either subject. If we presume that the function of this manuscript as a student's copy was also, for some reason, expired, then we can speculatively date the sketches to post-883.

The depiction of three wo in this manuscript therefore attests to knowledge of these foreign animals in Dunhuang. This is in keeping with Tang records that refer to such dogs as coming from afar and as being given by foreign peoples – making it likely that traders of such dogs would have passed through Dunhuang on the overland silk routes. Such dogs may even have been bought and sold in Dunhuang itself. Thus, these three creatures are not yaks, but are instead three lapdogs depicted in an artist's sketch on a perhaps discarded student Dunhuang manuscript and which dates at the earliest to the late ninth century. These sketches do not necessarily mean that the artist personally viewed these diminutive dogs. At this stage, we can only conclude that knowledge of these dogs and of the tropes associated with them clearly existed in Dunhuang.