Archiving as knowledge production: Research practices at Salt

In his book Stories of art, James Elkins criticizes the narrative of an art history that focuses on limited geographical regions and literature:

When art historians debate the survey course, the arguments usually turn on the major textbooks by Gombrich, Gardner, Stokstad, Honour and Fleming, and Janson. The situation is a little incestuous because those books are all in the same family: they were all written in the twentieth century in Western Europe or America. It has appeared in different times and places.Footnote 1

Elkin emphasizes that art history can never be limited to common subjects in non-Western geographies. In the publication, he discusses ways of ‘being fair to all cultures while also telling a story of art that is our story, fitted to our culture and our needs.’Footnote 2

Archives and their accessibility also play a crucial role in historiography. Today, archival initiatives concentrate on the histories of historical artistic practices that a variety of factors, including wars, dictatorships, institutional neglect, and a hungry art market, have ignored, buried, or hijacked.Footnote 3 Turkey's history of modern and contemporary art has also been short of fundamental research. Safeguarded mainly through private individuals, primary sources are dispersed in different hands with little public knowledge of their existence. Contributions to art history are limited as research outputs are created using common bibliographies and secondary sources. This situation coincides directly with the problems of historiography that Elkins identifies in the publication.

SaltFootnote 4 has aimed squarely at expanding the collective knowledge of visual production in Turkey after the 1950s, focusing on a group of critically important but underappreciated artists, sharing sources and documents of tangible and intangible heritage, and surveying the field from a broader perspective than an isolated national story. The institution assembles extensive archives for common use and pursues research with outputs such as publications, visualization projects, and public programs. Archives on the history of art in Turkey at Salt ResearchFootnote 5 bring together extensive materials on artistic practice, comprehensive artist archives, landmark exhibitions, and art institutions from the mid-century onward. These sources, which are accessible online, aim to shed light on the artistic environment of the late 20th century in Turkey and help to reevaluate history from local, regional, and international historical perspectives.

Salt Research collaborates with archive keepers, such as artists, historians, or curators, who have successfully preserved materials to bring these archives together. However, processing these archives and making them accessible requires an almost archaeological effort. To create a consistent narrative, it is necessary to trace the trajectory of the period's artistic environment. Only by thorough investigation, which includes posing inquiries and verifying information from several sources, can this be achieved. The archivist is tasked with identifying and cataloging the resources to make them accessible to the public.

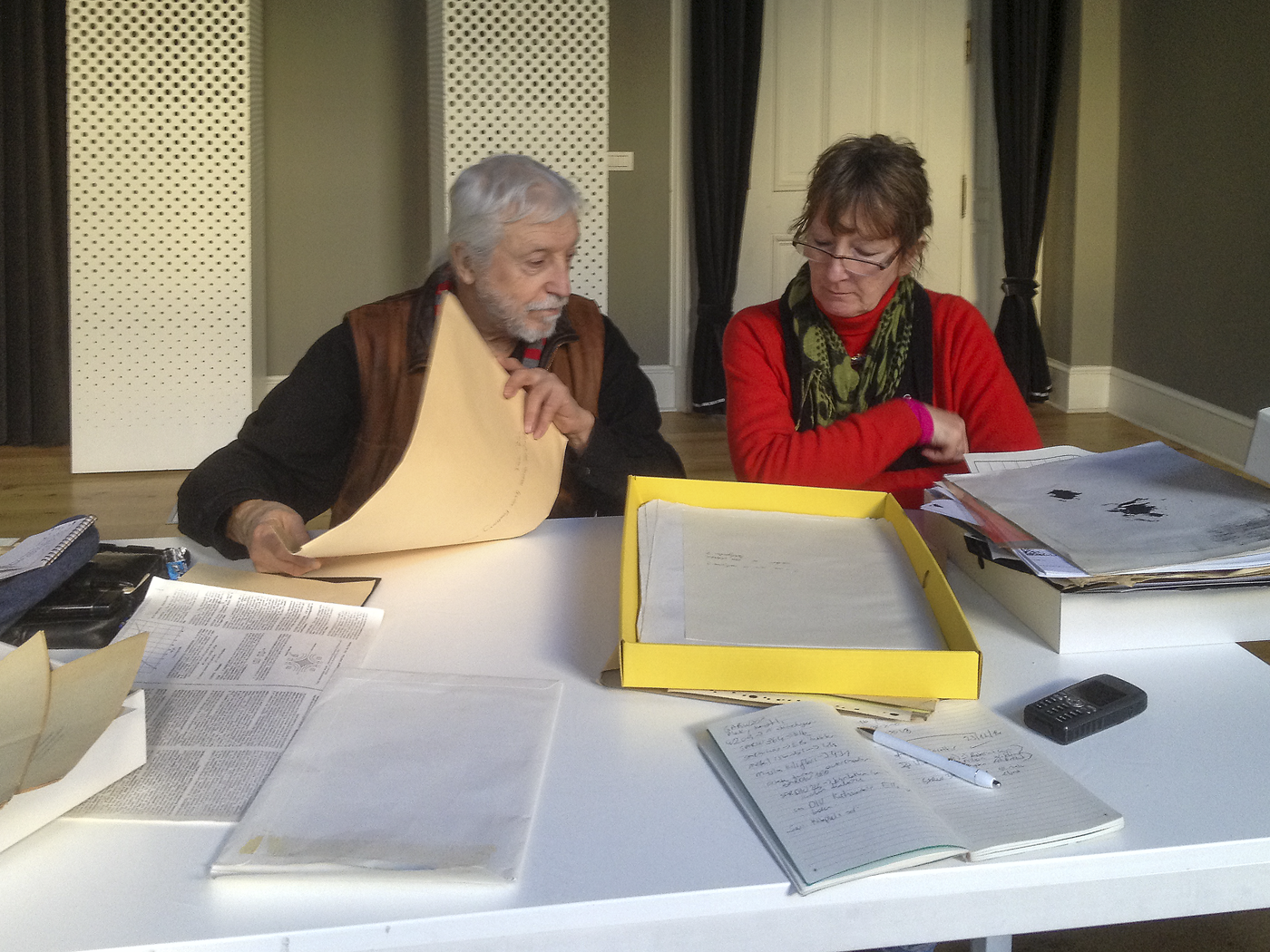

Fig. 1. İsmail Saray's archive before the cataloging and digitization processes at Salt Research, Salt Beyoğlu, 2013

Photo: Duygu Demir

Ideally, we expect archivists to coordinate or perform classification, cataloging, and digitization workflows. Cataloging is, in a sense, the identification of archival materials by the archivist, that is, the entry of all elements that provide information about the content and their presentation to the user. At times, exhibitions, spaces, or institutions that have never been heard of are discovered during this process.Footnote 6 Instead of merely overseeing archives waiting to be saved and revived by users, an archivist generates material and initiates new research projects. This situation also reflects the changing position of an ‘archivist’ as a curator, with specialist skills associated with archival management beginning to emerge.Footnote 7 The archivist, acting as a researcher, historian, or editor, influences researchers' understanding and use of archival content.

Research institutions act as intermediaries to maintain and impart knowledge to the larger community of researchers and users. Salt aims to extend knowledge by assembling archives and exploring them through diverse methods and programs. The relationship between research methods and programs can vary from one project to the next or according to the institution's conditions. An archive and related research can evolve into an exhibition, or an exhibition can lead to an archive and a research project. In addition to the exhibition, one can visualize and present research projects in various formats like digital projects, public programs, or publications.Footnote 8 Salt takes on “each project as a laboratory for experimentation that may intersect”Footnote 9 with these outputs. Vasıf Kortun, the founding director of Salt, explains the institution's research-centric mission as follows:

Focusing upon research and treating what we work with as potentially discursive objects, Salt becomes more involved in the actualisation of said objects’ capacity. As such, the question is not about custodianship but shaping novel narratives and, telling multiple histories of art. There is never one story. History is not fixed, and any attempt to invent a canon is delusional or authoritarian or both delusional and authoritarian.Footnote 10

The institution also believes that public archives on distributed networks and user participation play a key role in knowledge production. These networks provide a digital platform where users can contribute, allowing wide digital access to any user beyond geographical barriersFootnote 11 and enabling the establishment of new links among them. Reflecting the multi-layered nature of data at Salt Research, they also prompt new narratives without centralizing the institution.

The following selected research and archive projects aim to offer an overview of Salt's approach to knowledge production. These projects investigate the concept of the archive in terms of transparency and contingency. They present a variety of research methods for interpreting, presenting, and accessing archives.

“Open” archive beyond the institution

Salt was founded in 2011 and inherited the capacities and knowledge of three institutions: Platform, Garanti Gallery, and the Ottoman Bank Archives and Research Center.Footnote 12 The institution brought together the archives of these institutions specialized in different disciplines under Salt Research and prioritized making them available online during its foundation.

Salt supports the idea of an “open” archive available for everybody, not only for professionals or academic-level researchers. The institution explores possible relationships between archives, democracy, and transparency, as well as ways to engage with its users through various projects such as ‘Out of the Archive’, and ‘Researchers at Salt’. Salt adopts innovative tools and networks, explores ways to adapt them to the institution's existing infrastructure, and opens them to a discussion through its programs.

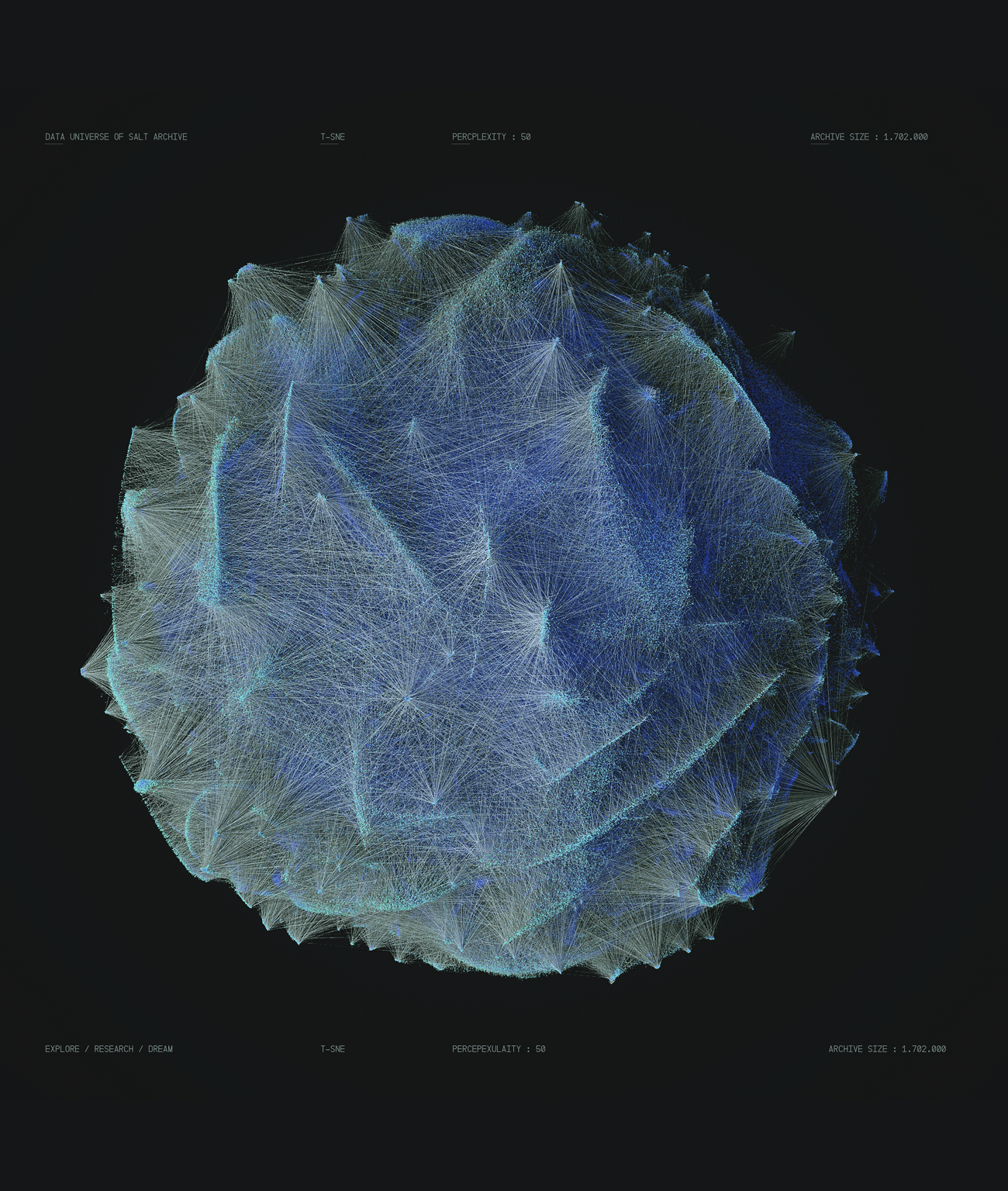

Fig. 2. Refik Anadol, image from Salt Research data process, 2017

Courtesy the artist

In 2017, Salt invited artist Refik Anadol (1985-, Turkey) to work with Salt Research collections, which at the time consisted of over 1,700,000 digital objects. Anadol employed machine learning algorithms to search and sort relations among these documents. Shortly after receiving the commission, Anadol was a resident artist in Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence (AMI) program. Interactions of the multidimensional data found in the archives were, in turn, translated into a media installation Archive dreaming at Salt Galata.Footnote 13 Developed during his residency, the project offered an insight into how the multi-layered structure of the archive could be presented by machine intelligence.

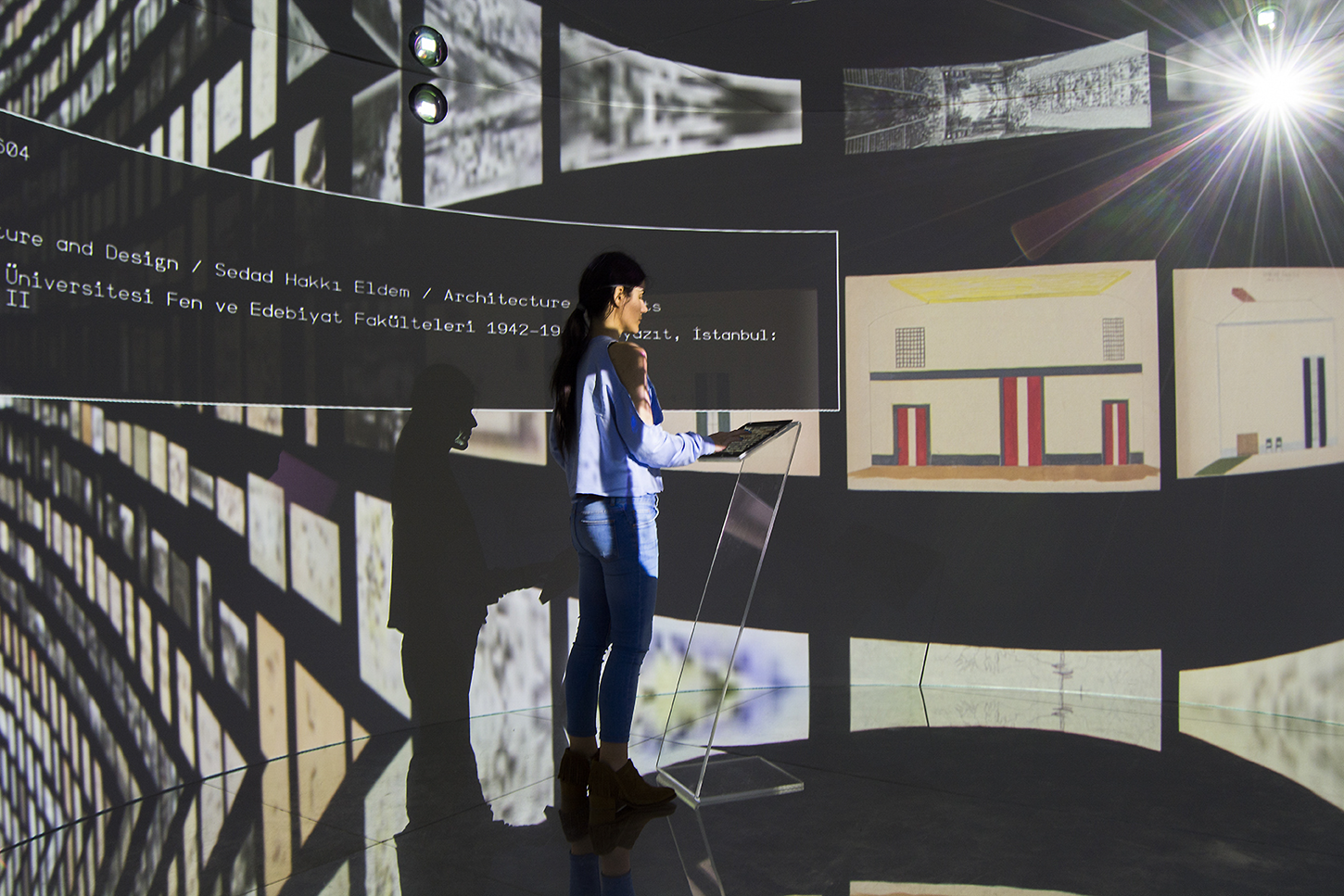

Fig. 3. Refik Anadol, Archive Dreaming, Salt Galata, 2017

Photo: Mustafa Hazneci

Google indexed and made the metadata hosted by saltresearch.org available via the search engine during the same period. As a result, the archives became far more publicly available off the institution's website. Kortun interprets this attempt by the institution as follows: “The archive is realized outside the institution, constantly corrected and revised by the public, and the outside is much more intelligent than the institution.”Footnote 14

Contingency

In 2012, Salt began an archive project with the artist Ahmet Öktem (1951- , Turkey). Öktem took photographs of each exhibition he participated in from the 1970s to the early 1990s. The Ahmet Öktem Archive at Salt Research brings together these photographs and various ephemera collected by the artist. Salt came across the photographs of the First May exhibition for the first time during the digitization and cataloging process of the archive. The exhibition was organized by the Visual Artists Association on the same day as the May 1st Massacres in 1977 in Taksim Square (Istanbul, Turkey).

Fig. 4. Installation view from the Visual Artists Association's First May Exhibition, Palace of Sports and Exhibitions, Istanbul, 1977

Salt Research, Ahmet Öktem Archive

Fig. 5. Installation view from the exhibition “Scared of Murals”, Salt Beyoğlu, 2013

Photo: Mustafa Hazneci

These photographs paved the way for a research project examining artist's rights in Turkey and the relationship of art with society, economy, labour, politics, and censorship practices in the period from 1976 to 1980. The exhibition “Scared of Murals”Footnote 15 was organically developed out of these data. Discussions were held via public programs, e-publications were published and compiled, and archival material was made accessible online at Salt Research.

Mapping as a method

Mapping can be an alternative way to retrieve knowledge when the archives are not compiled or accessible. In 2016, Salt initiated a new research project on Turkey's participation in international biennials between 1957–1987. The first phase of the research aimed to determine the biennials, participating artists, biennial editions, commissars, and curators. This information was compiled collectively with the support of researchers in the field and individuals who experienced the period. The institution commissioned researchers abroad to access the archives of the Venice Biennale, the Paris Biennale, and the São Paulo Biennale. This data was visualized and presented on a map which is open to the contribution of users with their corrections and additions. The map revealed various links including economic, political, institutional, and artistic changes, as well as local, regional and international relationships, and women's visibility in the art world.Footnote 16 Through this mapping project, the institution seeks to fill in the gaps in the history of the biennials and invites users to contribute to the research.

Fig. 6. From the mapping project on Turkey's participation in international biennials

In 2019, Salt's path intersected with art historian Aynur Gürlemez Arı, whose PhD thesis examined Turkey's participation in the Venice Biennale between 1895–2017. Coincidentally, Salt's and Gürlemez Arı's research interests overlapped during the same period. Gürlemez Arı mentions that she used the map as a reference in her thesis before making a research trip to Venice to study the archives at The Historical Archive of Contemporary Arts (ASAC). Gürlemez also adds that she used images from the exhibition archives and correspondence from the Italian Embassy Archive at Salt Research as primary sources in her thesis.Footnote 17

Fig. 7. Sabri Berkel in front of his painting Mehtap [Moonlight], 1962

Salt Research, Yusuf Taktak Archive

Gürlemez Arı learned that Sabri Berkel (1907–1993, Turkey) participated in the Venice Biennale with his painting Mehtap [Moonlight] during her studies at The Historical Archive of Contemporary Arts (ASAC). The researcher also came across the artist's photo in front of the painting at Salt Research. This connection encouraged her to write a text on Sabri Berkel's participation in the Venice Biennale in 1962. In 2021, she expanded the scope of her research by focusing on other international biennials and submitted an article on Turkey's participation in the 1957 São Paulo Biennial. These textsFootnote 18 were published on the Salt Blog.

In 2023, Salt initiated a collaboration with Gürlemez Arı to publish her PhD thesis. The e-publication is available on Salt's website.

Incompleteness

In 2012, Salt began a research project on the artist İsmail Saray (1943-, Turkey and UK), who held a crucial place in the advanced art of the 1970s and early 1980s in Turkey; the project aimed to re-introduce a figure about to drift out of its narrative to art history. Saray has been living in London since 1980; he is indifferent to being in the spotlight, which made it all too easy to disregard his role in the art history of Turkey.

In 2014, the artist's archive, comprised of documents and audiovisual materials, was processed and made available online at Salt Research. The first phase of the project was shared in the form of an exhibition titled From England with love, İsmail Saray at Salt Galata in Istanbul and later in Ankara (2014–2015). In March 2018, Salt published the İsmail Saray book, the first monographic publication on the artist.

Fig. 8. İsmail Saray and his wife Jenni Boswell-Jones working with the artist's archive, Salt Galata, 2014

Photo: Sezin Romi

In 2020, Salt received an email from the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Koroška (Slovenia) informing the institution that Saray's work EA-ARURU-KI (1975) is in the museum's permanent collection. The museum asked for further details about the work.

Saray produced this work in the Black Sea City of Samsun and sent it to Slovenj Gradec for the Peace 75 - UNO 30 exhibition in 1975. The artist's archive included only preparatory photographs taken before the work was sent to former Yugoslavia and the exhibition catalog. Since the artist could not remember the details, this information was indicated in Salt's publication in 2018: “The whereabouts of this work, which was produced in Samsun and sent to Slovenj Gradec, is unknown as it was not returned to the artist after the exhibition.”Footnote 19

Fig. 9. İsmail Saray, EA-ARURU-KI (1975), installation view from the exhibition Gallery for Peace, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Koroška (KGLU), 2020

Courtesy the museum

Then, the museum shared a letter from the archive stating that Saray had approved the acquisition of the work. This situation prompted the artist to reconsider and remember the details.Footnote 20 In May 2020, Saray participated in the Gallery for Peace Footnote 21 exhibition with his work EA-ARURU-KI after 45 years. This led to the inclusion of additional sources into the artist's archive at Salt Research, echoing the following sentences in the foreword of the publication İsmail Saray:

While the book is the last leg of our project, it is by no means the last word on the artist. His archive holds the potential to surpass the cumulative work presented here, as new additions to Salt Research's holdings in general, as well as to the İsmail Saray Archive specifically, might reveal new information.Footnote 22

Compilation: Exhibitions in Turkey

It was a time of conversation was a research and an archive project. It revisited the story of three exhibitions that took place in Turkey in the first half of the 1990s. Exhibitions were the new curatorial and collective projects of their time, all organized during a period when art itself emerged as an object of knowledge and intersected with other disciplines, such as sociology and politics.

Fig. 10. Installation view from the exhibition It was a time of conversation, Salt Galata, 2012

Photo: Mustafa Hazneci

It was a time of conversation derived from Salt's interest in revisiting and interpreting past exhibitions that expressed an urgency when they were realized, producing and/or witnessing critical ruptures. The project emerged from extensive research and the compilation of materials on these three unique curatorial and collaborative exhibitions. Although only thirty-four years separate their occurrence from today, little information and very few documents could be found. Documents, videos, and photos were compiled with the exhibition's organizers, artists, and assistants. Interviews were conducted with them. The research was visualized as an exhibition at Salt Galata (2012) and Salt Ulus (2013). The e-bookFootnote 23 was published as part of the project, and compiled archives became accessible online at Salt Research.

Conclusion

“How does the institution decide to initiate archive and research projects?” is one of the most frequently asked questions posed to Salt. There is no definitive answer to this question. It differs depending on contingencies, circumstances, and the course of the research. While archives to be digitized and made accessible can be planned, sometimes a topic or an incident encountered through a conversation, a reading, or a document can spark new curiosities and research. Each archive contains potential subtopics waiting to be explored. These are usually not foreseeable at the beginning of the project but become apparent as the research progresses and links are extended. Salt does not claim to undertake all of these projects itself; the institution is open to new collaborations with individuals and institutions from different backgrounds.

On the other hand, Salt supports the idea of archives accessible on distributed networks with the participation of a multitude of users. It explores ways to learn and apply innovative tools and discusses them through its programs. The institution prioritizes common use rather than ownership.

Salt never intended to function as a national archive. However, the inadequacy of the state archives and the volume of material that has grown in the institution over the years have positioned Salt as a reference point beyond expectations. In 2011, Salt Research combined the knowledge of three institutions specialized in “Art,” “Architecture and Design,” and “City, Society, and Economy.” As the archival collections expanded, new intersections and interactions between these and new fields have been revealed. This situation has paved the way for new holdings, such as graphic design and cinema at Salt Research.

When scrutinizing Salt's approach to knowledge production within art history, the art archives at Salt Research form a common trajectory. Compiled from various sources, they unveil a narrative transcending the established histories conveyed through specific institutional and individual standpoints. Salt believes that making resources accessible through an online catalog is not the last word in the research. On the contrary, it is the beginning. The archive is never “complete” and is of value only when it is layered with new outputs from different perspectives. The institution anticipates these resources and outputs will be integrated into the art history curriculum in Turkey, enabling the generation of new reference sources that expand upon the existing literature in circulation. Time will tell who will use the archive, when, and to what research it will contribute.