From the so-called “liberation of the South” (giải phóng miền Nam) in late April 1975 until 1989, Vietnam and its people encountered severe difficulties in practically every aspect – politically, ideologically, militarily, socially, psychologically, and economically. Arguably, the latter were the most serious and had the most debilitating impact on Vietnam’s people. In retrospect, several, often interrelated, factors contributed to this sorry state of affairs. It is impossible, on the one hand, to comprehensively describe, with any real justice, all of those factors and, on the other, ascribe the impact of each in a chapter of this nature. Accordingly, this chapter will briefly address the various reasons for the challenges experienced by Vietnam and its people in the period immediately following the end of the war before delving into and expounding upon the most critical among them.Footnote 1

The moment the war ended, the victorious authorities in Hanoi adopted a winner-takes-all attitude. A widespread slogan at the time, which was on the tip of the tongue of most officials from the North, was “ai thắng ai” (who is victorious over whom). Top party officials and policymakers justified this notion in ideological and theoretical terms as one of proving that “large-scale socialist production” (sản xuất lớn xã hội chủ nghĩa) through bureaucratic centralization would win in the battle against capitalism and its free-market system. They thus often ignored advice and analyses even from the Southern revolutionary leaders, dismissing some of the latter supposedly for insubordination while marginalizing many others. Lesser officials and bureaucrats from the North also tried to grab the lion’s share of victory in most areas.Footnote 2 They perhaps acted even more crudely than the carpetbaggers after the American civil war. All the while they were aided and abetted by hordes of Southern opportunists known as the “April 30 revolutionaries” (cách mạng 30 tháng 4).

Premature Reunification and “Socialist Transformation”

The communist-led military takeover of Saigon brought about policy responses by the United States in the subsequent weeks and months that tended to bolster the positions of regime hardliners in Hanoi. One of these responses was the recommendation on May 14, 1975, by US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to the US secretary of commerce, that the strictest trade sanctions should be imposed on Cambodia and communist-controlled South Vietnam, just as they had been on North Vietnam.Footnote 3 Another response was the veto on July 30, 1975, by US Ambassador to the United Nations (UN) Daniel Patrick Moynihan, of the applications for membership by the two Vietnams as two separate states. The uncompromising stance of the United States had the effect of strengthening the hand of hardliners in Hanoi who favored early reunification with the South. Only two months after the US veto of the two independent Vietnamese applications to the UN, the Party Central Committee declared at its 24th Plenum in September 1975 that Vietnam had entered a “new revolutionary phase.” The tasks at hand were as follows:

To complete the reunification of the country and take it rapidly, vigorously, and steadily to socialism. To speed up socialist construction and perfect socialist relations of production in the North, and to carry out at the same time socialist transformation and construction in the South … in every field: political, economic, technical, cultural and ideological.

The Resolution of the 24th Plenary Session of the Party Central Committee stressed that in order to carry out socialist transformation and construction in the South, the “comprador class” and the “vestiges of the colonial and feudal land systems” had to be eradicated. To this end, the resolution emphasized that the most important task was to establish and strengthen the party system and the “people’s administrative system.”Footnote 4

Lê Vӑn Lợi, a seasoned Northern diplomat, later explained the reasons the leadership in Hanoi thought it was necessary to speed up the unification of the country and to expeditiously carry out socialist transformation and construction in the South:

After the liberation, in the South the revolutionary government administration was not yet strengthened, the administrative system of the pro-American regime at the provincial levels and the grass-root levels in reality were not yet dismantled, and tens of thousands of bureaucratic and military officials of this puppet regime were not yet under control administratively. This is a condition that could not be prolonged. There was a need for the unification of the country in terms of governmental administration.Footnote 5

Since both the government in Hanoi and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Southern Vietnam (PRG) in Saigon had often stated that they envisioned the reunification of Vietnam to proceed step by step over a period of twelve to fourteen years, and had shown confidence by submitting, in mid-July 1975, their applications for membership to the UN as two separate states, the view expressed above reflected a fundamental reassessment by the Hanoi leadership. It is difficult to gauge how much of this was based on newfound fears and how much was a justification for imposing Hanoi’s political and bureaucratic control. What was certain was that the conditions on the ground in the southern part of Vietnam, especially at the grass-root and provincial levels, could not have changed that drastically in a couple of months, since these were areas where the PRG had the strongest support throughout the war years.

In any case, in order to carry out socialist transformation and construction in the South, two programs were initiated: the first was “Transformation of Industry and Commerce” (cải tạo công thương nghiệp) and the other “Transformation of Agriculture” (cải tạo nông nghiệp). Party leaders perceived that the commercialization of the South’s rural economy, particularly production by the middle peasants, was tightly connected to the comprador capitalists (tư sản mại bản) in the urban areas. The term “tư sản mại bản” (literally, capitalists who sell the country) is borrowed from the Chinese term used during the Qing Dynasty (1636–1911) that referred to merchants and bourgeois manufacturers who traded with foreigners. Since this term has a negative connotation, its use in Vietnam during this period was probably meant to differentiate these people from the “national capitalists” (tư sản quốc gia) or “domestic capitalists” (tư sản quốc nội) for easier targeting and scapegoating.

Whatever the intention, the middle peasants produced large food surpluses in the South. If the government allowed them to maintain close ties with the capitalists in the urban areas, it would be difficult for the government to procure enough staples and other agricultural products to supply the urban population and the huge numbers of people in its administration and its military. According to a US Senate investigation, by 1972 South Vietnam had more than 10 million internally displaced “refugees” out of a total population of 18.5 million, mostly living in and around urban areas and refugee camps.Footnote 6 Therefore, transformation of the rural economy had to be tightly coordinated with the transformation of the private commercial and industrial sectors.

Before describing how the first program was implemented, it is necessary to mention the fact that many “comprador” bourgeois in Southern towns and cities were businesspeople who had given valuable support to the struggles for independence and freedom. This support included donating money to the revolutionary cause, providing lodging and residences to cadres and fighters, participating in antiwar movements, denouncing US intervention, and opposing the policies and conduct of the Saigon regime. After the war ended, however, most of those people who were still engaged in commercial and industrial activities became targets of the transformation program. This policy change was explained, both ideologically and theoretically, by the fact that the revolution had by now moved from the “popular democratic stage” (giai đoạn dân tộc dân chủ nhân dân) to the “socialism stage” (giai đoạn xã hội chủ nghĩa). This meant that the revolution had moved from the period of struggle for national independence, when the main contradiction was between the entire Vietnamese nation and foreign interventionists, to the period of domestic struggle between different classes in order to solve the question of “who wins over whom” between capitalism and socialism within Vietnam.

Armed with the above ideological justification, the Politburo ordered the Party Standing Committee to formulate a plan for attacking the comprador class, which was given the code name “X1.” This operation was carried out in two stages. The first stage started in the middle of the night of September 9, 1975, when ninety-two persons called “leading compradors” (tư sản mại bản đầu sỏ) were arrested. Forty-seven others were summoned for questioning, three escaped, and one committed suicide. Despite the scope of the operation, the amounts of money and valuables seized were meager according to the official inventory recorded at the time. For example, there was a total of: 900 million đồng of the former regime’s currency (1,000 đồng was equal to $1 in 1974, but by late 1975 the currency had become practically worthless); $134,578 (of which $55,370 were in bank accounts); 1,200 French francs; 135 Thai Baht; 7,691 taels (about 850 lbs) of gold; 4,000 pieces of diamond jewelry; 97 pieces of jade jewelry; and 701 watches of all types. In terms of other assets, the operation confiscated: 60,435 tons of fertilizer; 8,000 tons of chemicals; 3,031,000 meters of fabric; 229 tons of aluminum; 1,295 automobile tires; 27,460 bags of cement; 136 air conditioners; 96,604 bottles of brandy and wine; 2,000 pairs of eyeglasses, etc.Footnote 7

One wonders why the regime had gone through all the trouble and created such social, political, and psychological turmoil in order to reap such meager results. Either the inventories were faked by the cadres involved in carrying out the campaign or the “leading compradors” were really never that wealthy. In any case, perhaps because the high officials felt that they had not obtained what they thought they could, the second stage of the operation was carried out from December 4 to December 6, 1975. This time around the cadres managed to seize 288 establishments in total – of which 64 were in the industrial sector, 10 were agricultural, 82 were commercial, and the rest in other fields. The total value of all these assets was estimated at slightly above 31 million đồng, which was equivalent to about $10 million US by the official exchange rate at the time.Footnote 8 These numbers suggest that either there was asset-stripping or the properties seized were intentionally undervalued – or both.

As it conducted the two operations against the comprador class, the government carried out a program to send urban dwellers who were considered “nonproductive” – many of whom were merchants – to the so-called “New Economic Zones” (NEZs, vùng kinh tế mới) in rural areas that had been abandoned during the war years. Many displaced war refugees were also sent back to their former native villages. One of the main aims of this campaign was to relieve the urban areas of social, economic, and political pressures. According to the official records kept by the Committee of Party Historical Research in Hồ Chí Minh City, as Saigon was renamed shortly after the country’s formal reunification, “during the first 15 days of October 1975 more than 27,000 inhabitants of the city had returned to their native villages or gone to the New Economic Zones.” During the month of October 1975, “100,000 inhabitants of the city went to the rural areas to construct New Economic Zones.” By official account, “in less than 5 months after liberation about 240,000 inhabitants of the city had enthusiastically returned to their former native villages and gone to the New Economic Zones.”Footnote 9 It is quite a stretch to maintain that these people had “enthusiastically” done so. As this author witnessed during his six-month research trip to Vietnam over 1979 and 1980, thousands of people who had been sent to the NEZs flooded back to Hồ Chí Minh City and were living on the sidewalks because they had run out of food supplies and/or because unexploded mines and ammunition were still in the ground, injuring and killing many people there. Nevertheless, according to official estimates, by the end of 1975 nearly 6 million refugees in the South had returned to their native villages. This resulted in critical demands for land and severe land disputes in the countryside.Footnote 10

The “transformation of agriculture” was carried out differently in the southern half of the country from how it was in the northern half. Since most of the rural areas in the North had already been collectivized, the government’s plan was to consolidate village cooperatives so that “large-scale socialist production” could be managed and coordinated, presumably more efficiently, at the district level. In southern Vietnam, peasant households were first encouraged to become members of the “production collectives” (tập đoàn sản xuất), purportedly in order to get them used to working together before moving them to the higher cooperative levels. These members pooled their means of production (such as land, buffaloes and cows, farm implements, and other capital inputs) and worked together in “unity production teams” (đội đoàn kết sản xuất), each composed of forty to fifty people who cultivated an average surface of 30 to 40 hectares. The administrative committee of each team included the head administrator, who was responsible for overall management, and two assistant administrators, who oversaw the particular tasks involved in planting and harvesting, rearing livestock, and performing other production activities. The responsibilities of the administrators and team members were to make sure that the production plans of the households would be feasible and would together become the common production plan of the whole team that, in turn, would meet the goals set by the central government. These goals included meeting government procurement quotas at price levels set by the government, making sure that materials purchased from the government and services provided by it would be paid on time, and a host of other matters.

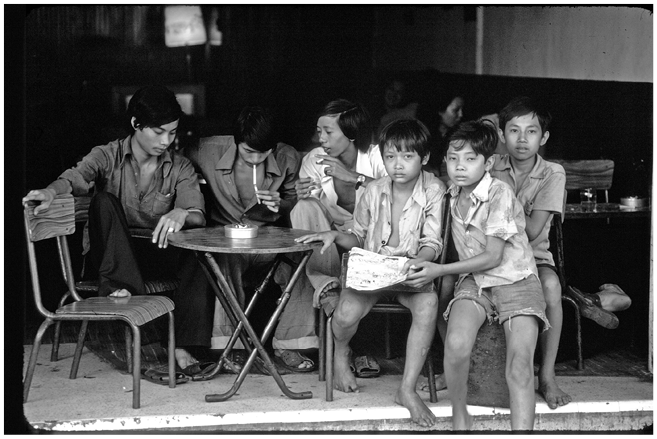

Figure 13.1 Young people sit in a coffee shop in Hồ Chí Minh City (April 20, 1980).

The “production collective” system in the south neither increased agricultural production nor food procurement for the government. Although in 1976–7 staple production (in terms of rice and rice equivalents) increased from 17 percent to 20 percent over the prewar years, this was mainly because of the redistribution of about 1 million hectares of land to the landless and the reclamation of about 1 million hectares of fallow land. Government food procurement (which included taxes and government purchases) actually decreased from 950,000 metric tons in 1976 to 790,000 metric tons the following year. Food production and procurement also suffered due to the escalating conflict with Cambodia and increasing tensions with China.

Impact of Conflicts with Cambodia and China

Beginning in January 1977, Khmer Rouge forces attacked across the Cambodian border into civilian settlements in six out of seven of Vietnam’s border provinces. Such attacks occurred again in April. The Vietnamese government decided not to retaliate at this point and instead sent a conciliatory letter to Phnom Penh proposing negotiations to resolve the border problem. The Khmer Rouge rejected this offer and continued with the attacks. In September and December, the Vietnamese counterattacked strongly, pulling back each time with an offer for negotiation. But each time Phnom Penh spurned the offer for talks and continued to attack Vietnamese territory, almost until the end of 1978. A reason for this intransigence on the part of the Khmer Rouge had to do with China’s aid and support. Between 1977 and 1978, China gave Pol Pot’s Cambodia several billion dollars in economic aid and supplied it with enough weapons to equip about 200,000 troops. An estimated 10,000 Chinese troops and technical personnel were also deployed to Cambodia to improve its military capability. During these two years of attacks, Khmer Rouge forces brutally murdered about 30,000 Vietnamese civilians, impelling tens of thousands to flee the border provinces. Many people in the NEZs abandoned their farmland and flooded back into Hồ Chí Minh City and other urban areas. Several hundred thousand Cambodian refugees also fled to Vietnam during those years.

In the face of these complicated developments, on April 14, 1978, the Hanoi Politburo issued Directive 43-CT/TW, which called for the vigorous “transformation of agriculture” in southern Vietnam. Collectivization had proceeded cautiously there, especially in the Mekong River Delta, until the beginning of 1978. But now the Party leadership was willing to take a gamble that, by getting the peasants into a collective framework, the government would be able to procure food more effectively in the effort to feed the burgeoning urban population and the armed forces. In response to the conflicts with Cambodia and China, some 300,000–400,000 men and women had by now been added to the various armed services, while hundreds of thousands of refugees had flooded into the cities. In 1980, the total number of people in the armed forces and in the urban areas was estimated at 11.5 million out of a total population of around 50 million. Another primary goal, similar to what had happened in 1975, was to relieve pressure in the urban areas by sending more of their inhabitants into the rural areas, where they could be isolated and controlled.

Connected to the goals mentioned above, the party leadership was now bent on an “all-out transformation policy” (chủ trương cải tạo triệt để) of the commercial and industrial sectors. In order to be able to do this, beginning in early 1978 leaders and cadres who had been involved in the transformation campaigns in 1975 were replaced. Nguyễn Vӑn Linh, the chair of the Transformation Committee for the South in 1975, was transferred to another position. On March 23, 1978, a secret campaign was carried out whereby all privately owned enterprises were simultaneously searched. All merchandise, raw materials, and means of production were confiscated. Large, privately owned industrial enterprises were transformed into “joint enterprises” (công ty hợp doanh), while smaller ones were organized into “production collectives.” Privately owned commercial enterprises were totally dismantled; meanwhile, small retail businesses were transformed into “service collectives” (tổ dịch vụ). Many merchants were sent to the NEZs to put fallow land under cultivation or to join production collectives. Only street vendors and manual laborers, such as bicycle repairers and barbers, were allowed to remain in the urban areas. A number of owners of large and medium-sized enterprises were arrested; many others fled abroad.

Hồ Chí Minh City was the focal point of the campaign, and an official report disclosed that 28,787 private commercial households were affected. Among them, 3,493 households were “deported” to rural areas. More than 2,500 households whose business enterprises had been dismantled, but whose members were later found to have been southern party cadres or strong supporters of the revolution, were allowed to remain in place and to work as government employees in various newly established enterprises slapped together from the privately owned ones that had been dismantled. In addition to the household members who were sent to the rural areas, 30,000 people fled abroad by various means.

Nguyễn Vӑn Trân, director of the Central Economic Institute when the campaign began, said later in an interview that the deportation of people to the NEZs was related to the belief by a number of top party leaders that, historically, the ethnic Chinese population of Chợ Lờn, a twin city of Saigon/Hồ Chí Minh City, had undermined the economic and political position of Vietnam for a very long time. Combining the transformation campaign with the deportation of a number of households from this area would prevent the return of some of these problems in the future. He added further that reliance on reports by unethical “April 30 revolutionaries” because of shortages of cadres on the ground caused distortions to the formation and implementation of the policies, thereby creating “extremely bad consequences.”Footnote 11

One of the “extremely bad consequences” had to do with the fact that, since many of the commercial capitalists were ethnic Chinese, this gave China the opportunity to accuse Vietnam of racial discrimination and thereby to terminate all aid and all trade by mid-1978. Trade with China had accounted for 70 percent of Vietnam’s foreign trade. Much of China’s aid consisted of consumer items, such as hot-water flasks, bicycles, electric fans, canned milk, and fabrics. Without these items, the government had little to offer the peasants for their produce in order to encourage them to increase production. China also increased the military pressure on Vietnam by shelling across Vietnam’s northern border on a regular basis. More significant still was the opportunity that the hardliners in Vietnam gave China to win over the hardliners within the US foreign policy establishment who wanted to use Vietnam for a proxy war against the Soviet Union. Since this would bring about huge problems for Vietnam and the whole Southeast Asia region for the next decade or so, a brief summary of the circumstances leading to this is necessary here.

While Vietnam was confronted by domestic difficulties and mounting problems in its relations with Cambodia and China, in the United States the Democratic Party had won the White House. After assuming the presidency, Jimmy Carter sought to improve relations with Vietnam for a number of reasons, including creating peace and stability in the Southeast Asia region. After a period of “feeling out,” the United States and Vietnam began a series of negotiations in May, June, and December 1977. During the first round of talks (May 3–4, 1977), the American side showed flexibility and suggested that the two sides should immediately establish diplomatic relations without preconditions. Other existing problems could be negotiated later on. The American delegation stated that the United States would not veto Vietnam’s application to be a UN member, but because of US laws Washington could not meet the promise stated in the 1973 Paris Agreement of giving Vietnam $3.2 billion “to heal the wounds of war.” However, the American side promised that after normalization of relations the United States would lift the trade embargo and consider humanitarian aid.

The counterproposal from the Vietnamese side was that the United States must accept a whole package, which included three items: (a) full diplomatic relations, (b) Vietnamese assistance in recovering American servicemen listed as missing in action (MIA), and (c) US reparations to Vietnam in the amount of $3.2 billion, as previously pledged by the administration of US President Richard Nixon. The biggest sticking point was the latter issue. During the second round of negotiations (June 2–3, 1977), the US delegation repeated its offer made in May. The head of the Vietnamese delegation, Phan Hiền, flew back to Hanoi and pressed for flexibility on the issue of aid/reparations, but the top party leaders would not budge. On July 19, 1977, the United States withdrew its veto on Vietnam’s UN membership as an indication of its good will before the third round of talks (December 19–20, 1977). At this third round of negotiations the American delegation suggested that if the two sides could not reach an agreement on establishing full diplomatic relations, then they could create Interest Sections in each other’s capital. In the latter case, the trade embargo could not be lifted right away. But Vietnam still insisted on the whole package that it had presented at the first round of talks.

On May 20, 1978, Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Carter’s national security advisor, went to China to discuss the normalization of relations between the two countries. The previous day, Deng Xiaoping, the “paramount leader” of China, was reported in the press as saying that China was the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) of the East, whereas Vietnam was the Cuba of East Asia. Given this development, it is not certain whether the top leaders in Vietnam still had any hope of normalizing relations with the United States. But for the next few months Vietnam offered, both publicly and through the offices of such countries as France, Sweden, and the Soviet Union, to drop the precondition for economic aid and promised to help the United States wholeheartedly in solving the MIA issues. On July 31, 1978, Vietnamese Premier Phạm Vӑn Đồng told an American delegation in Hanoi led by Senator Edward Kennedy not only that Vietnam had dropped the precondition for US economic aid in order to normalize relations with the United States, but that Vietnam also truly wanted to be a good friend of the United States.Footnote 12 Upon his return, Senator Kennedy called upon the US government to establish diplomatic relations with Vietnam, to lift the trade embargo against Vietnam, and to give Vietnam aid “according to the humanitarian traditions of our country.”Footnote 13 This was followed by meetings between US Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke and the Vietnamese foreign minister at the UN headquarters in New York on September 22 and 27, 1978, to discuss the normalization of relations between the two countries. The two agreed on normalization without any preconditions.

According to Brzezinski, on September 28, 1978, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance sent President Carter a report on the details of the agreement to normalize relations with Vietnam and recommended that normalization should proceed immediately after the congressional elections in early November. Brzezinski, a staunch Cold Warrior, strongly opposed this recommendation. According to Brzezinski, as of October 11, 1978, he had been successful in getting President Carter to drop the decision to normalize relations with Vietnam.Footnote 14 Instead, at the end of October 1978, “Vietnam was presented with a set of preconditions it could not possibly meet in the current situation.” Recognition, the United States now maintained, could not occur until three issues had been resolved to its total satisfaction: “the near-war between Vietnam and Cambodia; the close ties between Vietnam and the Soviet Union; and the continued flood of refugees from Vietnam.”Footnote 15

Fearing that the tough stance by the United States would encourage both Cambodia and China to stage a pincer attack on Vietnam, in early November 1978 Vietnam signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union. On December 15, the United States announced normalization of relations with China. On December 25, Vietnam invaded Cambodia in order to preempt a pincer attack, claiming publicly that it went into Cambodia to save the Cambodian people from the genocidal Pol Pot regime. In late January 1979, Deng Xiaoping arrived in the United States for a visit and announced that China would “teach Vietnam a lesson.” He asked President Carter for “moral support” for the forthcoming Chinese punitive war against Vietnam. In his memoirs, Brzezinski disclosed his concern that President Carter would be persuaded by Cyrus Vance’s advice and would ask Deng Xiaoping not to use force against Vietnam. Therefore, Brzezinski stated that he did everything in his power to ensure that President Carter would support China.Footnote 16

Early in the morning of February 17, 1979, several divisions of crack Chinese troops simultaneously attacked Vietnam along the entire length of the northern border and went on to occupy Vietnam’s six northern provinces. Six divisions invaded Cao Bằng province, and three divisions were used against each of Lạng Sơn and Lào Cai provinces. It was widely reported that during their occupation Chinese troops reduced the six northernmost Vietnamese provinces to rubble and committed many atrocities. What is less known is the fact that after withdrawing from the said provinces, Chinese troops still continued to attack Vietnam across the northern border until 1989, causing much loss in lives and property. For example, the Battles of Vị Xuyên in Hà Giang province in April and May 1984 cost the lives of nearly 2,000 Vietnamese troops. From 1979 to 1989, China consistently refused to accept Vietnam’s proposals to hold talks to discuss the border issues, putting forth preconditions that included Vietnam’s total withdrawal from Cambodia and denunciation of the Soviet Union. Some of China’s top leaders even said publicly that they wanted to stretch Vietnam out and bleed it white as part of their proxy war against the Soviet Union. As a result, Vietnam had to maintain about 1.6 million soldiers for the defense of the northern and western borders.

The maintenance of such a large military force required increased supplies of food and materials. However, the “socialist transformation” campaigns in the rural and urban areas had already disrupted production capabilities and supply chains, creating severe shortages in food and in almost all other commodities. In the rural areas of the south, many peasants who refused to enter the collectives and the cooperatives left 1.8 million hectares of their land uncultivated out of a total of 7 million hectares in the entire country. Food procurement by the government, in terms of tax and purchases, decreased to 613,000 metric tons in 1979, as opposed to 1.1 million metric tons in 1976, 989,000 metric tons in 1977, and 716,000 metric tons in 1978.Footnote 17 Meanwhile, many former merchants and skilled workers from the urban areas who had been sent to the countryside to work in the newly established collectives did not have the means of production and the necessary skills to put the land under cultivation. Added to these problems was the fear that a prolonged war with China and with the remnants of Pol Pot’s army in Cambodia would bring about much more hardship and suffering. A combination of these and other factors led an increasing number of people in all regions of Vietnam to flee to other countries in search of safety and opportunities. The exodus from Vietnam during this period has been estimated at around 600,000 people. While many of these refugees encountered severe hardship and unspeakable tragedies, the exodus also created much criticism of Vietnam by other countries in the region, thereby contributing to its further isolation from the international community.

From Stop-Gap Measures to “Renovation”

Instead of reexamining the basic reasons behind the problems produced by the transformation campaigns, Hanoi embarked on a series of stop-gap measures to try to remedy them. For example, on November 18, 1980, the prime minister’s office issued the decree code-named 306-TTg ordering employees in all government offices and state-owned enterprises to go, by rotation, to rural areas about 25 to 30 miles (40 to 50 kilometers) in distance from the cities to put under cultivation land that the collectives and cooperatives had left fallow. Since government offices and enterprises had by now ballooned with employees who did not have much work to do, as a result of the transformation programs, it was not difficult to send them every month to the rural areas to till the land and raise livestock. The problem was that the costs involved in getting these government employees to these rural areas exceeded many times over the values of the things they could produce.

Stop-gap measures of this nature lasted for several years, in spite of courageous attempts by intellectuals and officials at various levels to voice their opinions on what they thought were the underlying problems. Many cadres were dismissed from their positions, while many independent intellectuals were driven to leave the country, since they realized not only that their interventions would not be listened to, but that their personal welfare would also be compromised. At the same time, however, the dire conditions in the country brought about a groundswell of resistance to the failed government policies and programs in every region and in most sectors of the economy. This grass-roots movement, which involved the participation of local inhabitants and officials both in rural and urban areas, lasted from 1979 to 1986, and had many ups and downs. This became known as a period of “fence-breaking” (phá rào) to indicate the efforts at tearing down the barriers that had been set up by the government at all levels to obstruct local and national development. Most of the time, however, these efforts involved subtle, indirect maneuvers to avoid direct confrontation with the authorities. In fact, the movement for renting out cooperative lands to household bidders for a certain agreed-upon percentage of the crops was initially called “sneak contracts” (khoán chui). Eventually, its name changed to “household contracts” (khoán hộ) and “two-way contracts” (khoán hai chiều). The overall effect was to force the central government to begin incrementally the process of reforms that culminated in the policy called Đổi mới (Renovation) in 1986.Footnote 18 But the real fruits of this change in outlook and policies only came after the withdrawal of all Vietnamese troops from Cambodia in the early 1990s.

Conclusion

After the so-called “liberation of the South,” Vietnamese leaders plunged Vietnam into more than a decade of difficulties on all fronts because of overconfidence, ideological steadfastness, and miscalculations. Domestic resistance and international pressures of various natures eventually brought about grudging changes that finally culminated in the reform process that opened up a new horizon for Vietnam and its people.

On the surface, 1975 appeared as a triumphal year in the decades-long history of postcolonial revolution. The year began in high spirits as progressive revolutionaries around the world continued to celebrate the fall of the Portuguese Empire in southern Africa and the rise of Angola and Mozambique as independent states. Rhodesia and the apartheid regime in South Africa now appeared as the key battlegrounds in the war against colonialism in Africa. Perhaps equally encouraging was the news that Yasser Arafat, leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), had delivered a hugely successful address on the floor of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in late November 1974. Arafat and his comrades had worked hard to identify their struggle with a broad alliance of revolutionary forces across the world that included Cuba, China, Algeria, and North Vietnam. Palestinian fighters cast themselves as Arab Che Guevaras – part of a rising generation of liberation warriors waging a struggle against oppression that reached from the rice paddies of Southeast Asia, to the rocky hillsides of South Lebanon, south to the plains of southern Africa, and across the Atlantic in the rainforests of Central America. News of the PLO’s success was only the beginning. Revolutionary armies in South Vietnam and Cambodia continued to make gains through the early months of 1975 that, by April, brought them to the gates of Saigon and Phnom Penh. The decades-long battle for liberation in Southeast Asia seemed as if it was drawing to a triumphal close. The implication of these events could not have been less than heartening for progressive revolutionaries across the wider world.

Despite appearances, this Third World secular-revolutionary triumph would be short-lived. Although many contemporaries saw the victory of the Vietnamese Revolution as a transformative moment in the Cold War, subsequent events around the world suggested that a very different set of changes were underway. Even as peoples around the world celebrated the victories of 1974 and 1975, the unraveling of the progressive revolutionary project in the developing world was well underway. Changes taking place in the wider international system would transform the revolutionary playing field during the 1970s and 1980s. This chapter locates the communist victory in Vietnam in a regional and global context – that of what Odd Arne Westad has aptly termed the Global Cold War. It first situates the Vietnamese Revolution as part of a broader wave of communist revolutions in East Asia before turning to examine the impact of the Sino-Soviet split in Hanoi and around the wider postcolonial world. From there, the chapter identifies the mid-1970s as a key moment in the unraveling of the Third World secular-revolutionary project. It then concludes by looking at the 1980s and the rise of competing forms of postcolonial revolution.Footnote 1

Conventional interpretations of the 1970s tended to treat the post-Vietnam period as the nadir of US power and influence in world affairs – a view shared by many contemporaries and given voice by Ronald Reagan’s “Let’s Make America Great Again” presidential campaign in 1980. Recent histories of the 1970s by US historians have challenged this understanding, suggesting instead that the decade witnessed a series of cultural, political, and economic revolutions that paved the way for a resurgence in the 1980s and 1990s.Footnote 2 A similar shift has taken place in the field of international history as scholars reexamine these transformations in the global sphere. The slow pace of declassification in Western countries, combined with the significant obstacles to archival access in many Third World states, has played a large role in this dearth of studies. Nevertheless, several general worksFootnote 3 together with more specific studiesFootnote 4 have begun to throw new light on this period. With the passage of time, and the end of the Cold War, the 1970s appear not as a triumph for the forces of Third World communism but rather as a tipping point in the story of their unraveling.

Viewed in the longer term, Hanoi’s victories in 1973 and 1975 appear as the final triumphs in a string of East Asian communist conquests stretching back to the late 1940s. The resumption of the Chinese civil war between Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Jiang Jieshi’s Guomindang government in 1946 marked the beginning of a communist strategic offensive that would span the next three decades. The Chinese civil war, the French Indochina War, the Vietnam War, the Korean War, the Massacre of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), and the Cambodian civil war each occurred as part of this offensive that would serve to transform the region. To observers in Western capitalist countries, it appeared as if the East was indeed turning Red. Although officials in the Eisenhower administration would first articulate the domino theory, fears of communist contagion and the spreading influence of both Moscow and Beijing dated back to the 1940s.

Furthermore, there was no reason to expect that such upheavals would be limited to East Asia. The entire postcolonial world – and developing countries in Latin America – appeared vulnerable to communist influence. In particular, Mao Zedong’s doctrine of People’s War seemed tailor-made for what was to become the Third World. While Karl Marx had seen an industrial proletariat as the engine of communist revolution and V. I. Lenin had looked to a hardened vanguard of revolutionaries, Mao identified the people – and in China’s case the peasantry – as the source of revolutionary energy. In Mao’s formulation, agrarian societies could leapfrog the stage of industrial-capitalist development and move directly into a communist revolution. Likewise, the People’s War promised to serve as a blueprint for guerrilla armies hoping to defeat better-armed conventional forces backed by wealthy states. Mao and the CCP’s success served as a tremendous source of inspiration for revolutionaries around the world. Third World fighters – using a highly modified version of Mao’s playbook – won a string of victories in the Korean War, the French Indochina War, and the Algerian War that appeared to validate these Maoist ideas. Indeed, by the late 1960s, it appeared as if Third World guerrilla forces might be unstoppable.

The Unraveling World Revolution

However, these triumphs masked a deeper set of problems. While prevailing opinion in the West tended to see international communism as a monolithic force in the Cold War, deep fissures existed between the two most influential communist powers, the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union. Tensions between Chinese and Soviet communists stretched back to the Chinese civil war. Mao would never forget Stalin’s reluctant and partial support during the darkest days of the Chinese Revolution. And Stalin’s death in 1953 only served to make matters worse. With Stalin gone, Mao had good reason to see himself as the reigning patriarch of the international communist movement. But Soviet leaders had no inclination to surrender their claims to leadership of the world revolution to the CCP. Nikita Khrushchev’s rise to power and his 1956 “Secret Speech” further strained relations between Moscow and Beijing. Mao and his comrades viewed Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin and his repudiation of his predecessor’s cult of personality as an attack on key tenets of the CCP’s authority. The Soviet military intervention in Hungary that same year also worried Beijing – how long would it be before Moscow chose to send its forces against China in order to keep the CCP in line? Conversely, Khrushchev’s willingness to engage in “peaceful coexistence” with the Western powers seemed to signal that the Kremlin intended to abandon the cause of world revolution – a cause that still appeared urgent to Beijing. The Soviet Union’s refusal to back China in its 1962 war with India marked yet another slap in Mao’s face. Under the weight of these indignities, Mao and his comrades were only too happy to needle the Kremlin following its diplomatic defeat in the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Beijing was quick to denounce Moscow’s failure to live up to its commitments in the postcolonial world, as well as the Kremlin’s Marxist “revisionism.” It was in response to Beijing’s attacks – more than in an attempt to challenge US power – that Khrushchev had announced Moscow’s support for “wars of national liberation” in the Third World in early 1961. By the early 1960s, the Sino-Soviet split was tearing the Third World’s global revolution apart.Footnote 5

Indochina would emerge as a key battleground in the nascent struggle between Moscow and Beijing. Whereas both communist powers had cooperated to restrain the more militant factions of Hanoi’s leadership during the 1954 Geneva Conference, the Sino-Soviet split created new opportunities for North Vietnamese leaders such as Lê Duẩn to pursue the military reunification of North and South Vietnam. With both Moscow and Beijing looking to burnish their Third World revolutionary credentials, Vietnam became a proving ground for both powers. Beijing would support Hanoi as its East Asian protégé while Moscow used North Vietnam to prove its continued commitment to wars of national liberation. In this way, Lê Duẩn and his comrades were able to gain military, political, and economic support from both communist powers. In the short run, then, the Sino-Soviet split opened doors for revolutionaries in such places as Hanoi. However, in the longer term, the increasing acrimony between China and the Soviet Union boded ill for the cause of postcolonial revolution.Footnote 6

A clear example of the fallout from the Sino-Soviet split came with the 1965 annihilation of the PKI – the largest nongoverning communist party in the world. Like North Vietnam, Indonesia had become a battlefield in the contest between Moscow and Beijing. However, unlike North Vietnam, Indonesia had a third contender for influence – the United States. While China and the Soviet Union struggled over the PKI and Indonesia’s left-leaning, charismatic President Sukarno, Washington built influence in the Indonesian Army. Many of the details of what happened in the summer and fall of 1965 have been erased, destroyed, or hidden, but scholars have offered a likely reconstruction of what followed. Spurred on by the Sino-Soviet competition – and possibly by US CIA machinations – the PKI appears to have staged a preemptive attack on September 30, 1965 on top leaders in the Indonesian Army, which the PKI suspected of planning a coup against Sukarno. While six high-ranking commanders were murdered in the attack, key officers – most notably Major General Suharto – survived. The army responded by launching a nationwide crackdown against the PKI that quickly escalated to a quasi-genocidal massacre. In the coming months, army forces, Islamic youth movements, and ordinary Indonesians slaughtered hundreds of thousands of PKI members and associates. US officials recognized that purge as a victory for American interests in Southeast Asia’s most populous nation. Time magazine summed up the mood in July 1966 when it described the annihilation of Indonesia’s communists as the “West’s best news for years in Asia.”Footnote 7

In retrospect, the massacre of the PKI was as representative – and as strategically significant – as Hanoi’s victory over the Saigon regime. The Sino-Soviet split had divided Indonesia’s communists and created a situation in the autumn of 1965 in which they either overplayed their hand or fell into a trap set by US-backed military officers. Through the second half of 1965 and 1966, Suharto consolidated control over the Indonesian government and established a pro-US military regime in Jakarta. For all intents and purposes, Indonesia was now firmly in the Western camp – Washington’s darkest fears of falling dominoes would not come to pass. Even if Vietnam and the rest of Indochina fell to the communists, the region’s largest and most strategically important nation was in the hands of a strong, reliably pro-Western military regime. As US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara later explained, the destruction of the PKI “significantly altered the regional balance of power [in Asia] and substantially reduced America’s real stake in Vietnam.” But the geostrategic implications of Suharto’s rise were mostly drowned out by the fury of America’s escalating war in Indochina.Footnote 8

Even as the Vietnam War intensified, the global communist movement was coming undone. The same forces that allowed Hanoi to play Moscow and Beijing off one another also set the stage for the slaughter of the PKI. But the drama of America’s war in Vietnam overshadowed these dynamics. So, too, did the successful efforts of Hanoi and the National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong) to reach out to the broader revolutionary world. Much like the Algerians before them, the Vietnamese recognized that the international landscape of the middle Cold War offered fertile ground for their diplomacy.Footnote 9 The global process of decolonization had transformed the international arena in the years since 1945. The UN General Assembly would grow a membership of several dozen states to nearly 200 during these decades. As a result, the Western powers would find themselves increasingly outnumbered in key international forums by new, postcolonial nations in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Many of these new states held deep sympathies with fellow peoples struggling for national liberation. Furthermore, the emergence of the nonaligned movement in the 1950s created new international networks linking postcolonial states, national liberation fighters, and progressive forces. By the early 1960s, aspiring revolutionaries such as those in Vietnam found an array of eager supporters in the so-called Third World.

Vietnamese communist leaders embraced this notion of “guerrilla diplomacy” by reaching out to groups around the radical world. In the United States and Western Europe, millions of leftwing students, civil rights activists, and progressives came to celebrate the cause of the Vietnamese liberation fighters and denounce the “imperialism” of the United States and South Vietnam. Revolutionary states in the postcolonial world also made shows of support – even though their aid was vastly outweighed by that coming from Beijing and Moscow.Footnote 10

The Vietnamese communists – along with the Algerian and Cuban Revolutions – became a central driver in the formation and proliferation of what has been called the myth of the heroic guerrilla that arose during the 1960s.Footnote 11 For a time, Third World liberation fighters seemed nearly invincible. From Mao and Ahmed Ben Bella to Hồ Chí Minh and Che Guevara, these national liberation fighters came to appear as the leaders of an unstoppable force in international affairs. Had Sukarno and the PKI’s demise received more attention, observers of international affairs might have drawn a different conclusion. But the high drama of the Vietnam War proved too mesmerizing. While Hanoi’s victories troubled Washington, they electrified revolutionary groups in the postcolonial world.

Among those transfixed by the war in Vietnam were Palestinian revolutionaries. Leila Khaled – who gained international fame as a strikingly attractive female aircraft hijacker – would write that the Palestinians “must learn the secrets of the Vietnamese.” The largest Palestinian guerrilla group, Fatah, published translations of Võ Nguyên Giáp’s writings in its series “Revolutionary Studies and Experiences” alongside studies of the Chinese, Algerian, and Cuban Revolutions. In March 1970, Hanoi would host a delegation of Palestinian liberation fighters, including Yasser Arafat. The Palestinians toured government and military facilities and met with such leaders as Giáp. “The Vietnamese and Palestinian peoples have much in common,” he told the Arab visitors, “just like two people suffering from the same disease.” Throughout their struggle, Palestinian fighters would seek to identify themselves with the Vietnamese. The Jordanian capital of Amman would be an “Arab Hanoi.” Fatah’s moral victory in the 1968 battle of al-Karamah would earn comparisons with the concurrent Tet Offensive in South Vietnam. The fact that both South Vietnam and Israel were key recipients of US aid reinforced these associations, as did revelations that Israeli military officials had visited Saigon to observe US counterinsurgency operations in Southeast Asia. By the late 1960s, many – though certainly not all – leftwing political activists in Western Europe and North America would place Arafat alongside Che Guevara and Hồ Chí Minh as icons of a globalized struggle against colonialism in all its forms.Footnote 12

No single episode of the war had greater global resonance than the 1968 Tet Offensive. Although the offensive itself proved to be a military failure, the political impact reverberated around the world. In the United States, Tết proved to be a tipping point in convincing a majority of Americans that the war was not being won. As the public began to turn against the conflict, the antiwar movement gained momentum. On campuses and the streets of cities across America, students and political activists rose up against the established order. Moreover, these movements were not confined to the United States. Large protests broke out in multiple countries in what historians have identified as a global moment. These uprisings owed much to the communist triumphs in Vietnam and the Tet Offensive in particular. Anti-war sentiment proved to be a key rallying point for various groups of activists protesting. African Americans fighting for civil rights, disgruntled students protesting conditions in major American and European universities, environmentalists, women fighting for equal rights, and others found common cause in their opposition to the American war in Vietnam.Footnote 13

Once again, however, appearances proved deceiving. Even as the Tet Offensive and the global uprisings of 1968 appeared as sweeping victories for the international forces of revolution, the Sino-Soviet split continued to widen. In the summer of 1969, clashes along the Soviet–Chinese border escalated to a low-level border war between the two communist powers. Although the death toll only reached into triple digits, the potential for a wider conflict remained. Indeed, in September 1969 Soviet diplomats communicating with US officials quietly floated the prospect of staging a preemptive strike against Chinese nuclear facilities – a move that would very likely have sparked a wider conflict between Moscow and Beijing. Although the Kremlin chose not to launch such an attack, it was clear to all that Sino-Soviet relations were not what they had once been. To many Chinese leaders, the Soviet Union – and not the United States – appeared as the greatest foreign threat. Thus, even as the communist triumphs in Vietnam seized the world’s attention, the seeds took root for a massive geostrategic realignment between Beijing, Moscow, and Washington.

The Tipping Point

These two threads – the revolutionary and geostrategic – would converge in East Pakistan in 1971 in a war that created the state of Bangladesh. Having suffered a brutal crackdown at the hands of Pakistani military forces in the wake of the Awami League’s electoral victory, East Pakistani separatists launched an armed insurgency to achieve full independence for Bangladesh. Western journalists touring the battlefields noted the striking similarity between the wars in Bangladesh and Vietnam. Meanwhile, Bangladesh liberation fighters – Mukti Bahini – identified their common cause with Vietnamese revolutionaries. Both were fighting foreign occupations backed by the United States; both would use guerrilla tactics to achieve victory. But the liberation of Bangladesh would also contain a more ominous dimension for the forces of progressive revolution. In the latter stages of the conflict, as India and Pakistan went to war against one another, the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) moved into alignment. Both Washington and Beijing feared Moscow’s ambitions in South Asia, and both supported Pakistan as a counterweight to India. Moreover, US President Richard Nixon was using Pakistan as a backchannel in his bid to “open” China. During the darkest days of the India–Pakistan conflict, Nixon would reach out to Beijing to request the mobilization of Chinese military forces along the border with India. Though Beijing balked at Nixon’s suggestion, the larger implications were clear: the Sino-Soviet split had transformed the relationship between the world’s three greatest powers.Footnote 14

The following February – 1972 – Nixon shocked the world by visiting China. Nixon’s trip capped a long series of negotiations that brought about a rapprochement between Washington and Beijing. This realignment transformed the triangular relationship between the United States, the Soviet Union, and China, and helped to ensure that the Sino-Soviet split was irreparable. Henceforth, Washington and Beijing would partner on various projects designed to thwart Soviet foreign policies and diminish the Kremlin’s standing in the world. In the wake of this opening to China, Washington’s stakes in the Vietnam War dropped even lower. Accordingly, Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, redoubled their efforts to bring the war in Vietnam to a close, now with the intermittent support of China. Leaders in Beijing also recognized that their best interests lay in aiding an American withdrawal from China. Although the Nixon administration staged a furious and ultimately futile series of campaigns to secure the survival of Saigon, the decision to pull out of South Vietnam had effectively been made. And while the Saigon regime struggled to hold on – bolstered by substantial infusions of US aid – Hanoi prepared for a final offensive to secure complete control of Vietnam. In March 1975, North Vietnamese forces launched their last campaign against South Vietnamese troops. Communist units stormed south, reaching the gates of Saigon in early April. Washington evacuated its remaining personnel while tens of thousands of Vietnamese fled on boats.Footnote 15

From the perspective of the Global Cold War, then, the North Vietnamese victories in 1973 and 1975 proved decidedly pyrrhic. Hanoi had reunified Vietnam under communist rule, the Saigon regime had been destroyed, and Washington’s South Vietnamese modernization project had been defeated. But while the drama in Vietnam held center stage, the Sino-Soviet split, the massacre of the PKI, and Nixon’s opening to China transformed the structure of power in the wider postcolonial world. Over this same period, the Nixon administration also established a new approach to fighting the Cold War in the Third World under the auspices of the Nixon Doctrine. The roots of this approach stretch back at least to the 1950s and the publication of Henry Kissinger’s first major foreign policy article, “Military Policy and Defense of the ‘Grey Areas’” in 1955. In the article, Kissinger argued that Cold War nuclear strategy and Dwight Eisenhower’s policy of mutually assured destruction effectively guaranteed that a superpower clash over core areas such as Central Europe or Japan would set off a full-scale nuclear war. However, nuclear retaliation was less effective for so-called “grey areas” – peripheral regions of secondary geostrategic importance. He wondered, was the United States prepared to risk a Soviet counterstrike against New York or Chicago in order to defend US interests in Indochina, Burma, or Afghanistan? Kissinger argued that the United States must maintain the ability to intervene in such areas if it hoped to defend its position in the Third World.Footnote 16 In less than a decade, American troops would be engaged in just such a venture in South Vietnam. But as Kissinger and other US officials discovered, the American public remained unconvinced of the need to sacrifice tens of thousands of American lives to maintain such commitments. The Nixon Doctrine would ultimately emerge as an attempt to defend American interests in peripheral areas without sacrificing large numbers of American lives. Perhaps indigenous forces – armed, trained, and funded by the United States – could serve as local police powers in the Third World.

Although Nixon’s failed “Vietnamization” scheme is the best-known example of the Nixon Doctrine, the idea was applicable to much of the Third World. A key inspiration for these ideas arrived in the months leading up to the Tet Offensive at the far western corner of southern Asia. In June 1967, the State of Israel launched a spectacular preemptive strike against the Egyptian and Syrian Air Forces. In less than a week, the Israeli military soundly defeated its Arab neighbors and occupied the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Sinai peninsula. Because Israel was a pro-Western nation and Egypt and Syria were aligned with the Soviet Union, the 1967 Arab–Israeli War also appeared as a stand-in for a hypothetical clash between North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and Warsaw Pact military forces. To many Americans, Israel appeared to have succeeded while US troops in Vietnam continued to struggle. If Washington could find more allies like Israel, the United States might gain the upper hand in the Cold War battle for the Third World. The 1968 Tet Offensive and the slow, painful failure of US policy in South Vietnam ultimately reinforced this lesson: rather than rolling back the Kremlin’s influence, it might be enough to raise the cost of any future communist gains by pouring resources into pro-Western allies in the Third World. Americans could afford to pay the bills as long as no US soldiers were coming home in body bags.Footnote 17

By the early 1970s, Nixon Doctrine aid had begun pouring into Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Brazil. America’s heavily armed Third World allies might not be able to reverse the tide of leftwing revolutions in the postcolonial world, but they could make any communist gains tremendously bloody – and they could do so without sacrificing significant numbers of American lives. As was the case in 1967, Israel again provided a key model for fighting Third World revolutionaries. In the years following 1968, the PLO had tried to emulate the Algerian and Vietnamese models by coordinating armed operations on the ground with a global diplomatic campaign in the international arena. PLO leaders reached out to revolutionary groups and leftwing regimes around the world, securing the political support of the majority of the world’s community by 1974. As Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish mused, “In the conscience of the people of the world, the torch has been passed from Vietnam to us.” At the end of that year, the UN General Assembly voted to recognize the PLO as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people and granted the organization permanent observer status – a significant victory for a liberation movement that controlled no official territory. But in contrast to Algerian and Vietnamese revolutionaries before them, Palestinian leaders were unable to translate these diplomatic victories into progress on the ground. With the firm backing of the United States, a massive influx of arms, and the cover provided by a US veto in the UN Security Council, Israeli leaders scorned UN resolutions and dug in their heels in opposition to the PLO. The following year, 1975, the PLO found itself embraced at the UN but locked out of Palestine and embroiled in a vicious civil war in Lebanon.Footnote 18

On the other side of the continent, in Southeast Asia, the forces of postcolonial revolution still appeared energized. The spring of 1975 brought two triumphs that electrified the millions of people around the world who had cheered the Vietnamese Revolution: on April 17, Khmer Rouge forces seized Phnom Penh; thirteen days later, Saigon fell to the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the NLF. April 1975 thus brought not one but two victories for the Third World forces of revolution. But those celebrating these triumphs had reason to pause. After capturing the capital of Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge forced tens of thousands of Cambodians out of Phnom Penh, compelling those that survived grueling marches along the roads to settle in the countryside. Next door, Hanoi prepared to send thousands of Vietnamese citizens who had worked with the Saigon regime to reeducation camps.Footnote 19

Furthermore, despite their shared communist ideology, deep animosities existed between Phnom Penh and Hanoi. During much of the American war in Vietnam, Vietnamese forces had used Cambodian territory as a rear base – the notorious Hồ Chí Minh Trail ran through Cambodia’s remote eastern regions. This reality brought Vietnamese and Cambodian fighters into close proximity. Khmer Rouge forces benefited immensely from the Vietnamese presence inside Cambodia, gaining shelter, a limited supply of weapons, and training at the hands of more experienced Vietnamese guerrillas. But these experiences also bred resentment. Vietnamese commanders often treated the Khmer Rouge as subordinates in their own country, and the Vietnamese always placed priority on their own revolution over that of the Cambodians. Moreover, the Vietnamese presence inside Cambodia invited ferocious US reprisals. American B-52s carpet-bombed the Cambodian rainforests while commandos staged limited raids into the country in search of the elusive Vietnamese communist headquarters. Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia in the spring and summer of 1970 unleashed widespread devastation across the eastern reaches of the country.Footnote 20

These festering resentments would rise to the surface after the Khmer Rouge victory in 1975, creating a Cambodian–Vietnamese split to match the Sino-Soviet one. Cambodian leaders began by marginalizing – and eventually executing – their comrades who had spent large amounts of time in Hanoi. At the same time, the party put forward a highly chauvinistic and xenophobic program that aimed to expel all foreign influence from Cambodia and seal the country off from future outside meddling. While these policies expelled Westerners, they also targeted Vietnamese – officials and civilians alike. As the Khmer Rouge transformed Cambodia into a massive forced labor camp, they laid plans to exact revenge on their Vietnamese neighbors. Beginning in 1977, Khmer Rouge forces staged a series of border raids into Vietnam. Hanoi initially responded to these attacks on a tit-for-tat basis, but as the violence escalated to several full-scale massacres, Vietnamese leaders determined that more drastic action had to be taken. In 1978, Hanoi assembled a government-in-exile composed of Cambodians who had fled the Khmer Rouge and began preparing for a full-scale invasion of Democratic Kampuchea.Footnote 21

On December 25, 1978, Vietnamese forces launched their attack. Some 150,000 soldiers supported by heavy armor crashed across the border and quickly forced Khmer Rouge units to retreat. In a matter of days, Vietnamese troops had reached Phnom Penh, and the Khmer Rouge leadership had abandoned the capital. Inside the city and across the countryside, Vietnamese soldiers found grisly evidence of the Khmer Rouge’s short and brutal time in power. After emptying the cities, the Khmer Rouge had forced hundreds of thousands of Cambodians into grueling agricultural labor. In an effort to stage a total revolution that would effectively turn the clock back to year zero, the regime tried to completely overturn the foundations of Cambodian society. After resettling the population, the Khmer Rouge separated children from parents, instituted an extensive regime of surveillance, and tried to transform the nation into an agricultural powerhouse. While the Khmer Rouge massacred thousands, its disastrous agricultural programs unleashed man-made famines across Cambodia that increased the death toll exponentially. In all, nearly 25 percent of Cambodia’s pre-1975 population perished under the Khmer Rouge reign. So shocking were these reports that much of the international left initially dismissed them as CIA propaganda. In the long run, however, the revelations of what life had been like inside Democratic Kampuchea did little to encourage foreign emulators.Footnote 22

Just as unsettling, for some observers, was the realization that two communist states – the products of successful revolutions that had triumphed less than two weeks apart – were now engaged in a fratricidal war. The worst was yet to come. In February 1979, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army launched an invasion of Vietnam. Beijing was now at war with Hanoi. The Sino-Vietnamese War would conclude in less than a month and leave somewhere around 60,000 people dead. Although short and strategically inconclusive, the symbolism of the conflict – and the larger Third Indochina War – reverberated throughout the communist and postcolonial worlds. The spectacle of three of the Third World’s most successful revolutionary states at war with one another devastated the illusion of global communist solidarity. Political scientist Benedict Anderson captured the gravity of the moment when he identified the Vietnamese–Cambodian and Sino-Vietnamese Wars as markers of “a fundamental transformation in the history of Marxism and Marxist movements” in the introduction to his seminal study of nationalism, Imagined Communities.Footnote 23 The Third Indochina War, the Sino-Soviet split, and the growing list of indictments regarding the human rights records of communist regimes crippled the appeal of leftwing politics for revolutionaries around the Third World. That same year, 1979, however, aspiring postcolonial revolutionaries would receive a new, dynamic, noncommunist model of liberation war.

The New Face of Revolution

The world’s next great revolution would appear in Iran. The Iranian Revolution began, like many other postcolonial upheavals, as a broadbased protest movement against an oppressive regime. Shah Reza Pahlavi had ruled Iran with an iron fist since a 1953 joint CIA–MI6 coup had reinstalled him in power. The Shah had remained a reliably conservative Cold War ally to the United States who secured massive amounts of Nixon Doctrine aid, which he hoped to use to build his nation into a major regional power. By the late 1970s, Iran’s forces fielded some of the most sophisticated military equipment in the US arsenal. Meanwhile, the regime’s secret police force, the SAVAK, enjoyed a fearsome reputation bolstered by its deep penetration of Iranian society, its working relationship with the CIA and the Israeli Mossad, and rumors of horrific torture techniques employed by its interrogators.Footnote 24 But none of this would prove sufficient to save the Shah’s regime. Disgruntled elements from across Iranian society – liberals, reformers, merchants, socialists, communists, students, and clergy – joined a wave of protests against the regime beginning in 1977. In the coming months, the protests grew to include tens of thousands of demonstrators. By late 1978, even US officials were coming to question whether the Shah could survive. In January 1979, the Shah – who had learned he was dying of cancer – chose to flee with his family rather than launch a military crackdown that would have guaranteed a massive bloodbath.Footnote 25

Initially, Iran’s broad revolutionary coalition remained mostly intact – but this was about to change. In February 1979, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned from his exile in France to massive crowds of cheering supporters. Khomeini and his allies quickly set about building up the clergy’s power in the new revolutionary regime and marginalizing rival factions. In short order, radical clergy were able to push aside more moderate leaders in the provisional government and assume positions of power. The hostage crisis at the US Embassy in Iran proved to be the last straw for the moderate holdouts in the regime – the path was now clear for Khomeini to assume total control. In this way, Iran’s revolution became the first large theocratic revolution of the twentieth century. This shift shocked contemporary observers around the world who had come to assume that modern revolutions were generally led by leftwing forces. Indeed, since the eighteenth century, the forces of revolution had tended to identify as liberal, socialist, or Marxist. Iran’s revolution reversed this historical momentum, signaled a structural shift in global politics, and dealt yet another blow against the secular, leftwing forces of Third World revolution.Footnote 26

Khomeini and his supporters borrowed elements from Third World revolutionary movements and saw themselves as liberation warriors in a similar mold to the Vietnamese. But in place of Marxism, Iran’s revolutionary leaders touted their Shi’a faith. The Iranian Revolution thus combined elements of political Islam with Third World revolutionary warfare. Indeed, the Iranian experience revealed the depleted state of the leftwing, secular politics in the postcolonial world. For a new generation of Iranians, Marxism did not appear as the most promising path to revolutionary change. This stemmed in part from the strong Shi’a faith held by many Iranians and, perhaps more importantly, from the fact that Iran’s clergy remained the best, organized institution in the country under the Shah’s reign that nevertheless managed to remain outside the regime’s control. But the collapse of worldwide communist solidarity with the Sino-Soviet split and the Third Indochina War dealt a devastating blow to the movement.

At the same time, the Iranian Revolution sent shockwaves across Central Asia and the Middle East. Iran’s eastern neighbor, Afghanistan, was also facing a challenge from Islamic revolutionaries. The previous year, communist forces had seized power in Kabul and created a Marxist regime. The new Afghan regime promptly bungled efforts to stage reforms and undercut much of what little popular support it had initially enjoyed. Infighting between rival Marxist factions and the murder of one of the key revolutionary leaders only made matters worse. These struggles placed Soviet leaders in a difficult position. Although many in the Kremlin doubted their Afghan comrades were up to the task of running the country, Moscow could not simply ignore the requests for assistance from a Marxist regime on its own borders. The unfolding revolution in Iran – which was destabilizing the region, leading the United States to expand its presence in the Persian Gulf, and leading some US officials to consider expanding relations with Kabul – added to this urgency. Ironically, the Iranian Revolution had also sown insecurities in Washington, where US officials feared that the Soviet Union might seek to expand its influence in the aftermath of the Shah’s departure. With tensions rising, Moscow decided to act: on the night of December 24, 1979, while Soviet troops moved across the border, KGB commandos staged an assault on the presidential palace in Kabul, killing Afghanistan’s president and installing Babrak Karmal in power.Footnote 27

The stage was now set for the last major battle of the Cold War. In a key sense, the tables had turned in the Soviet–Afghan War from earlier cases of Cold War insurgencies. Instead of a Western-backed government battling communist guerrillas, the Kremlin now supported a Marxist regime fighting against Western-backed rebels. In this same vein, the rebels – the Mujahideen, “the ones who struggle” – borrowed some of the techniques pioneered from leftwing fighters such as the Chinese, Algerians, Vietnamese, and Palestinians, but they had little use for Marxist doctrine. Rather, political Islam emerged as the prevailing ideological tendencies among the Mujahideen. Although many Mujahideen fighters and commanders were deeply religious and fought in defense of their faith, instrumentalist motivations figured heavily in this transformation. By the early 1980s, Islamist Mujahideen organizations enjoyed an overwhelming strategic advantage over their more moderate rivals.Footnote 28

In 1979, US President Jimmy Carter had committed to providing a modest amount of financial aid to Mujahideen guerrillas fighting the Marxist regime in Kabul. Carter’s support marked the beginning of what was to become the largest CIA covert operation of the Cold War, whereby the United States established a massive pipeline of aid to the Afghan rebels. Saudi Arabia provided matching funds that, together with CIA support, was funneled through Pakistani intelligence services (ISI) who provided on-the-ground contacts with the Mujahideen. Because CIA officers rarely entered Afghanistan, Washington effectively outsourced decisions as to which rebels received aid to the ISI. Pakistani officials – who hoped to use the Mujahideen as a bulwark against Indian influence in South Asia – chose to direct the majority of funds to Islamic fighters. In short order, the religious extremists became the best-funded and best-armed factions of the Afghan resistance.Footnote 29

Afghanistan would come to represent the centerpiece of the so-called Reagan Doctrine – an update of the Nixon Doctrine aimed at rolling back communism in the Third World not just by aiding conservative regimes, but also by providing aid to rightwing insurgencies. In the eyes of many US officials, the war in Afghanistan would become payback for Soviet aid to Hanoi during the Vietnam War. The aim of US policy in Afghanistan would be to create a “Soviet Vietnam” – a bloody, indecisive conflict engineered to kill thousands of Soviet soldiers and drain the Soviet economy. Whereas earlier periods had seen Moscow and Beijing functioning as key sources of foreign aid for revolutionary movements, Washington assumed this position in the final decade of the Cold War. Furthermore, Beijing also reemerged as a patron of the Mujahideen, forming a link in the foreign supply chain to the rebels, and effectively partnering with the United States in waging a proxy war against the Soviet Union.Footnote 30

If the long 1960s belonged to the Vietnamese Revolution, the 1980s belonged to the Mujahideen. The Vietnam analogies made by US officials would hold true for the Soviet–Afghan War with one glaring exception. Whereas Washington emerged from Vietnam in a stronger position vis-à-vis the Cold War, the war in Afghanistan would leave Moscow crippled. By the time the last Soviet troops left Afghanistan, the Soviet Union was spiraling toward collapse. Furthermore, if the fall of Saigon marked one of the last great victories for a Third World communist movement, the fall of Kabul in 1992 to Mujahideen forces was only the beginning of a larger story of the rise of Islamic revolutionary forces through much of the postcolonial world. Afghanistan descended into a vicious civil war between rival Mujahideen factions that, in 1996, gave an opening to a little-known Islamist movement calling itself the Taliban that would, five years later, burst onto the world stage as part of the September 11, 2001 attacks. The most notorious revolutionary of the twenty-first century would likewise emerge from the crucible of the Soviet–Afghan War. Osama Bin Laden launched his career as an Islamic militant as a minor figure in the anti-Soviet resistance. Through the 1990s, Bin Laden had built a potent, transnational force of committed Islamic fighters that would mount a global campaign of violence in the coming years.

Indeed, as the tides of the Cold War receded, the forces of Islamic revolution were on the march. Along the shores of the Mediterranean, PLO fighters – who had cast themselves as Arab incarnations of Vietnamese and Cuban liberation fighters and, in doing so, became darlings of the international left in the 1970s – faced a major internal challenge for leadership of the Palestinian liberation movement from Hamas, an extremist offshoot of the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood. Meanwhile, in Algeria – a state created by a Third World revolution that had inspired and been inspired by the Vietnamese example – an even bloodier fate awaited. When the religious party, the Islamic Salvation Front, appeared to be on the verge of a victory in the 1992 parliamentary elections, the Algerian military suspended the election, sparking a vicious civil war that killed perhaps over 100,000 people.Footnote 31

Figure 14.1 Afghan Mujahideen who fought against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (1980s).

Conclusion