John Conolly (Fig. 1) was born of Irish parents in the small market town of Market Rasen, Lincolnshire, in 1794. On leaving school he joined the army but after a few years he decided to study medicine. He graduated from Edinburgh University with the degree of MD in 1821. His dissertation, entitled De statu mentis in insania et melancholia, demonstrates an early interest in mental illness (Hunter Reference Hunter and Macalpine1963: p. 806). Between 1827 and 1831 Conolly was professor of the practice of medicine at University College, London, one of the first clinical professors to be appointed there (A Special Correspondent 1966). In 1830 he published a treatise on mental illness entitled An Inquiry Concerning the Indications of Insanity, with Suggestions for the Better Protection and Care of the Insane (Conolly Reference Conolly1830), suggesting a return to his earlier interest. In 1839 he was appointed resident physician, or medical superintendent, at the Middlesex County Lunatic Asylum (later Saint Bernard's Hospital) at Hanwell, London, in succession to Sir William Ellis.

FIG 1 Dr John Conolly. From Bewley (Reference Bewley2008), reproduced with permission of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Ellis was the first medical superintendent at Hanwell, having been appointed in 1831 when the asylum opened. He had previously served as the medical superintendent, with his wife as matron, of the West Riding of Yorkshire Pauper Lunatic Asylum at Wakefield from its opening in 1818 (Mindham Reference Mindham2020a). Regimens of care at Wakefield were derived from the practices of The Retreat at York (Tuke Reference Tuke1813; Mindham Reference Mindham2020b). Ellis brought the ethos of ‘moral treatment’ to Hanwell and believed that occupation for patients was therapeutic (Ellis Reference Ellis1838). Conolly was also aware of the work of Robert Gardiner Hill, who had demonstrated the feasibility of a regimen of non-restraint at the Lincoln Lunatic Asylum in 1838 (Gardiner Hill Reference Gardiner Hill1838; Mindham Reference Mindham2022).

Conolly resigned from his post as resident physician in 1844 following a disagreement with the asylum's committee over the authority vested in the physician but continued to serve as visiting physician until 1852. In 1846 his series of lectures on the construction and government of lunatic asylums appeared in The Lancet and formed the basis of the book discussed in this article.

The Construction and Government of Lunatic Asylums and Hospitals for the Insane

Architectural design

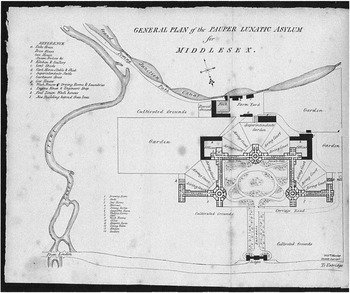

The first chapter concerns the siting, design and construction of asylums for the poor (Conolly Reference Conolly1847). Conolly favours the then recent legislation compelling authorities to make provision for poor people suffering from mental illness. The Middlesex County Lunatic Asylum at Hanwell was designed by the Quaker architect William Alderson. Construction work began in 1829 and the hospital opened in 1831 (Colvin Reference Colvin1995). The design was based on the panopticon principle propounded by the philosopher Jeremy Bentham and developed for large hospitals by William Stark at Glasgow and Watson and Pritchett at Wakefield (Mindham Reference Mindham2020a). The Glasgow asylum had a central observation tower and a radial plan; at Wakefield the layout was H-shaped with two observation towers and at Hanwell there was a double ‘dog-leg’ plan with three observation towers (Fig 2). At Hanwell there were gallery wards as had been introduced by Robert Hooke at the Moorfields Bethlem Hospital and subsequently used at Glasgow and Wakefield and in many other asylums (Mindham Reference Mindham2021). Conolly commends the use of gallery wards, with the provision of individual rooms for a high proportion of patients, but with additional day rooms to allow greater flexibility. He advises against the use of more than two stories for wards. He makes no reference to the use of the panopticon principle in the design of mental hospitals. This is rather surprising, as Hanwell followed this model, but may reflect the fact that problems with the panopticon were emerging and it was falling from favour. He discusses the need for balance between security and therapy and the separate care of patients with acute and incurable illness. Buildings should have a domestic character and not be oppressive in their appearance. He makes several references to the plans for the new Derbyshire County Lunatic Asylum at Mickleover (later the Pastures Hospital) by Paterson and Duesbury and commends many of its features (Richardson Reference Richardson1998). In particular he recognises the advantages of a corridor system, which allows each ward to be entered without passing through another. Conolly advised on the design of the Derbyshire Asylum and on the arrangements for it to be suitable for a policy of non-restraint.

FIG 2 Architect's drawing of the Middlesex County Lunatic Asylum at Hanwell. From Ellis (Reference Ellis1838), used by courtesy of the Wellcome Collection, Public Domain Mark.

Patient care

In subsequent chapters Conolly considers the care of patients in great detail. He makes recommendations on the arrangements for sleeping, observation, ventilation, heating and lighting. He stresses the need for cleanliness in every aspect of care: the washing and bathing of individual patients, the cleaning of the hospital, with special attention given to the sanitary arrangements, and the provision, washing and repair of clothing and bedding. He emphasises the importance of attention to the needs of the elderly and frail, the care of the sick and the desirability of having designated infirmary wards. Diet is seen as important in its quality, preparation and the way in which it is served. He sees exercise as important to both physical health and recovery from mental illness and recommends the provision of gardens and airing courts. An extension of this theme is his belief in providing occupation for patients, with different activities for men and women, often with an educational element. He comments on the different requirements of patients from higher social classes and the difficulty in providing suitable occupation for upper class women. He sees visiting by friends and relatives as desirable provided that it is properly supervised. At every instance he stresses the importance of a policy of non-restraint and the requirement that it extends to every area of activity.

The hospital attendants

Conolly commits two chapters to a consideration of attendants, both male and female. He sees the role of the attendants as central to the care, comfort and cure of patients and is in no doubt as to the demanding nature of this task. The selection of suitable persons to fill this role is of the greatest importance and he sees a key role for the medical superintendent in this procedure. Personal aptitude is important but Conolly asserts that ‘the first requisite for an attendant, if conjoined with a moderate share of understanding, is benevolence’ (Conolly Reference Conolly1847: p. 86).

Conolly lays out a scheme of work for attendants in great detail, beginning at an early hour and extending to bedtime and including participation in all meals. The attendants generally slept on the wards and the concept of a separate night staff was only just emerging. Patients were locked in their rooms at night and staff were able to observe them using a ‘spy-hole’ in the doors of bedrooms. Conolly notes the dangers of this practice in the event of fire and the need for strictly followed procedures in the event of emergencies. Seclusion of patients and the use of padded rooms is seen as a substitute for physical restraint but places great responsibility on staff of all grades in its supervision. Attendants accompanied patients to the asylum chapel at least weekly and participated in the services themselves. They had to watch their patients for untoward events during services, such as epileptic fits, and know how to deal with them appropriately. The visits of senior staff to wards is seen to be of great importance in its regularity and in fostering good relationships between staff and between staff and patients. He emphasises the therapeutic role of all staff at all times: ‘The greatest results desired in an asylum depend very much upon very small attentions, perpetually exercised’ (Conolly Reference Conolly1847: p. 94).

Religious observance, the chaplain and the asylum schools

In the final chapter Conolly considers the duties of the chaplain. He sees religious observance as important in the regulated life of the asylum for all its members, both patients and staff. All were expected to attend religious services on Sundays but many attended more frequently. The Anglican Church predominated but there was provision for patients to be visited by clergy of other denominations, notably Roman Catholics and Methodists. Conolly believed that attendance at services was beneficial to patients socially and spiritually, provided that ‘spiritual conceit’ and ‘religious fervour’ were avoided (Conolly Reference Conolly1847: p. 124 and 128). He also saw an important role for the clergy, as educated members of staff, in providing teaching in reading, writing and arithmetic for patients. This was often at a very basic level but, as Conolly comments: ‘As the lessons proceeded, it was found that more command was obtained by the patients over their powers of attention, and that they read with more confidence’ (Conolly Reference Conolly1847: p. 129).

At one point the visiting magistrates, who had overall responsibility for the asylums, ordered the closure of the ‘schools’ at Hanwell (Conolly Reference Conolly1847: p. 130). Conolly believed that the magistrates had been wrongly advised. In support of his view he refers to reports of the success of such schemes in France, Ireland and the USA as well as in England. Such experiences no doubt fed Conolly's belief that for an asylum to work well the medical superintendent should have absolute authority in clinical matters. Formal hierarchies of staff were not then fully developed but Conolly sees the need for the head nurse to be accountable to the medical superintendent in the interests of coordination of policy within the asylum: ‘He has to regulate the habits, the character, the very life of his patients. He must be their physician, their director, and their friend’ (Conolly Reference Conolly1847: p. 140).

The appendices

The appendices form an important part of the book. There are statistical details of other asylums in the British Isles but, as Conolly comments, these were not collected by uniform methods, which limits their usefulness. They are nevertheless of considerable interest. He discusses the care of patients regarded as incurable and recommends that all patients should be kept in a setting with full access to curative activities however hopeless their cases may seem to be. He gives interesting accounts of visits to schools for the insane at the Salpêtrière and Bicêtre hospitals in France, where he observed the instruction of patients and met members of staff who had promoted the activity. There are famous names among them. He gives an account of the conduct of religious services at Salpêtrière and of the orderly participation of patients. He reports positively on progress in the introduction of regimens of care without physical restraint in the British Isles. Conolly is not in favour of boarding-out schemes, which he believes expose patients to the risk of abuse. He makes particular reference to a scheme in which incurable patients from the west of Scotland were boarded out on the Isle of Arran.

Plans for asylums that allow a policy of non-restraint to be implemented and promote recovery of patients are appended. The plan of the new Derbyshire County Lunatic Asylum at Mickleover by Paterson and Duesbury is given particular attention. He comments on the advantages of the general layout and the care given to the arrangement of all services. The provision of independent corridors to all parts of the building is notable. The plan of the asylum at Halifax, Nova Scotia, prepared by the resident engineer at Hanwell, Mr Harris, and largely based on the Derbyshire Asylum, is commended by Conolly but he objects to the use of three stories even for use as school rooms. Mr Harris also drew up plans for an asylum in Colombo, Ceylon. This too was based on the Derbyshire model but with modifications to allow for the different climate. This plan was not adopted by the authorities in Ceylon. Conolly's comment on this decision summed up the whole matter of provision of buildings for the care of the insane: ‘it must always be remembered that the want of a properly constructed building, erected especially for the insane, constitutes an obstacle, almost insuperable, to the introduction of improvements of any kind’ (Conolly Reference Conolly1847: p. 183).

Conclusions

John Conolly vigorously promoted the care of the mentally ill without the use of methods of physical restraint. He also provided a detailed model of how it might be done and how the ethos of the asylum should be developed: ‘An asylum ought to be neither a prison nor a workhouse; but a place of refuge and of recovery from all the mental distractions incidental to mankind’ (Conolly Reference Conolly1847: p. 131). He contributed to the development of the administrative structure of mental hospitals and of the role of the medical superintendent. He continued to advocate a method of care without physical restraint throughout his career, culminating in his book The Treatment of the Insane without Mechanical Restraint (Conolly Reference Conolly1856). The influence of his work has been enormous.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.