Violence risk assessment and management are key components of clinical practice (Reference MonahanMonahan, 1992). In the UK, however, the adequacy and accuracy of risk prediction has been questioned in several inquiries into serious incidents involving mentally disordered patients (Reference ReedReed, 1997), and there is a growing emphasis on systematising protocols for risk assessment and management. More recently, the Government highlighted the issue of risk in those with ‘dangerous severe personality disorders’ (DSPD) and outlined new proposals for dealing with this challenging but illdefined group. Risk prediction is once again high on the public, political and clinical agenda. Here we review progress on violence risk assessment (particularly, violent recidivism) in the mentally disordered. We discuss recent developments in systematic violence risk assessment, focusing on the Psycho-pathy Checklist (PCL) as a predictor, and examine data from key meta-analytic studies in the field.

HISTORY OF VIOLENCE PREDICTION

Predicting future risk of violent behaviour has a long and difficult history. Before 1966 relatively little attention was paid to how well clinicians assessed risk. The Baxstrom v. Herald (1966) ruling in the USA (which resulted in the release or transfer from maximum security hospitals of 966 patients to the community or to lower security) was a notable landmark in risk assessment history. Steadman & Coccoza (Reference Steadman and Cocozza1974) reported on the 4-year outcomes of this cohort and found that only 20% had been reconvicted, the majority for non-violent offences. Throughout the 1970s several other studies reported in the literature fuelled the notions that clinicians had little expertise in predicting violent outcomes (e.g. Reference Cocozza and SteadmanCocozza & Steadman, 1976; Reference Thornberry and JacobyThornberry & Jacoby, 1979).

Monahan (Reference Monahan1984) reviewed these ‘first generation’ studies and concluded that “the upper bound level of accuracy that even the best risk assessment technology could achieve was of the order of 0.33”. He reported that the best predictors of violence among the mentally disordered were the same demographic factors that predicted violence among non-disordered people, and that the poorest predictors were psychological factors such as diagnosis or personality traits. Subsequent studies, however, challenged these conclusions, particularly those demonstrating links between rates of violent offending and specific clinical diagnoses (e.g. Reference Taylor, Gunn and FarringtonTaylor, 1982; Reference Binder and McNeilBinder & McNeil, 1988). The recent MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study (VRAS; Reference Monahan, Steadman and AppelbaumMonahan et al, 2000) also highlights the significance of clinical factors such as substance misuse and psychopathy as assessed by Hare's (Reference Hare1991) criteria, in the prediction of violent outcomes in nonforensic psychiatric patients discharged from hospital (see Steadman et al, Reference Steadman, Monahan, Appelbaum, Monahan and Steadman1994; Reference Steadman, Mulvey and Monahan1998).

GENERAL ISSUES IN VIOLENCE RISK PREDICTION

Clinical v. research perspectives

Clinicians have traditionally assessed violence risk on an individual basis, using a case formulation approach, i.e. ‘unaided clinical judgement’. Until recently, however, research tended to focus on the accuracy of risk prediction variables in large, often heterogeneous, populations using relatively static actuarial predictors. These divergent approaches have resulted in debate over the merits of clinical v. actuarial approaches and their relevance to risk prediction for groups v. individuals. Furthermore, they have resulted in different perceptions about the relative contribution of clinical items in risk prediction scales in forensic and non-forensic settings. The clinical v. actuarial debate, however, has also led to the development of violence risk prediction instruments which adopt a combined approach and recognise the importance of both static actuarial variables and the clinical/risk management items that clinicians normally take into account in risk assessments of individuals. The latter approach appears to be a first step in bridging the gap between clinical and actuarial measures, and between group and individual risk assessment approaches. In the following sections some of the key issues pertaining to clinical, actuarial and structured clinical assessments in violence risk prediction are discussed.

Approaches to violence risk prediction

Unaided clinical risk assessment

In clinical practice, assessments of the risk of dangerousness or violence in an individual are usually based solely on unaided clinical judgement. The unstructured clinical judgement approach to risk assessment has been criticised on a number of grounds, including low interrater reliability, low validity and a failure to specify the decision-making process (Reference Monahan and SteadmanMonahan & Steadman, 1994; Reference Webster, Douglas, Eaves, Webster and JacksonWebster et al, 1997a ), and inferior predictive validity compared to actuarial predictions (Reference MeehlMeehl, 1954; Reference Lidz, Mulvey and GardnerLidz et al, 1993; Reference MossmanMossman, 1994). Others, however, consider that clinical approaches offer the advantages of flexibility and an emphasis on violence prevention (Reference SnowdenSnowden, 1997; Reference Hart, Cooke, Forth and HareHart, 1998a ). Buchanan (Reference Buchanan1999) also suggests that clinical approaches, if they focus on mechanisms through which violence occurs, may enhance the validity of risk assessment.

Clinicians may be better than was believed in the immediate aftermath of Baxstrom studies (Reference Cocozza and SteadmanCocozza & Steadman, 1976). Gardner et al (Reference Gardner, Lidz and Mulvey1996), for example, showed that while actuarial measures were better than clinical ratings, clinical ratings were better than chance. Studies also showed that the accuracy of prediction can be enhanced when clinicians consider the context in which violence occurs in their patients (Reference Mulvey and LidzMulvey & Lidz, 1985). Recently, Fuller & Cowan (Reference Fuller and Cowan1999) showed that multi-disciplinary team consensus predictions of risk were comparable with actuarially based schedules over similar time-scales.

Actuarial methods

Actuarial methods allow assessors to make decisions based on data which can be coded in a predetermined manner (Reference MeehlMeehl, 1954). Decisions are made according to rules, and focus on relatively small numbers of risk factors that are known, or are thought, to predict violence across settings and individuals. For diverse samples and contexts, these factors tend to be static (e.g. demographic variables). Actuarial approaches undoubtedly improve the consistency of risk assessment, but Hart (1988a,b) argues that they tend to ignore individual variations in risk, overfocus on relatively static variables, fail to prioritise clinically relevant variables and minimise the role of professional judgement.

Despite these criticisms, actuarial risk assessment tools have been utilised for some time in US penal settings to help in making decisions about parole. Examples include the Base Expectancy Score (Reference Gottfredson and BondsGottfredson & Bonds, 1961), the Level of Supervision Inventory (Reference AndrewsAndrews, 1982), the Salient Factor Score (revised) (Reference HoffmanHoffman, 1983), and the Statistical Information on Recidivism (SIR) scale (Reference NuffieldNuffield, 1989). In the UK, similar measures have been developed to produce ‘risk of reconviction’ scores for prisoners before the parole board (Reference Copas, Marshall and TarlingCopas et al, 1996).

Structured clinical judgement

Structured clinical judgement represents a composite of empirical knowledge and clinical/professional expertise. Webster et al (Reference Webster, Douglas, Eaves, Webster and Jackson1997a ), who are the leading proponents of this model, argue that clinical violence risk prediction can be improved significantly if:

-

(a) assessments are conducted using well-defined published schema;

-

(b) agreement between assessors is good, through their training, knowledge and expertise;

-

(c) prediction is for a defined type of violent behaviour over a set period;

-

(d) violent acts are detectable and recorded;

-

(e) all relevant information is available and substantiated;

-

(f) actuarial estimates are adjusted only if there is sufficient justification.

Several instruments have been developed along these lines to assess risk of violence in clinical contexts. These include the Historical/Clinical/Risk Management 20-item (HCR-20) scale (Reference Webster, Douglas and EavesWebster et al, 1997b ) the Spousal Assault Risk Assessment guide (Reference Kropp, Hart and WebsterKropp et al, 1995) and the Sexual Violence Risk (SVR-20) scale (Reference Boer, Hart and KroppBoer et al, 1997) (see Douglas & Cox (Reference Douglas and Cox1999) for an in-depth review of these instruments).

Hart (Reference Hart, Cooke, Forth and Hare1998a ,Reference Hart b ) suggests that structured clinical instruments like the above promote systematic data collection based on sound scientific knowledge, yet allow flexibility in the assessment process. He also argues that, unlike strict actuarial measures, they encourage clinicians to use professional discretion.

Violence risk prediction in clinical settings

A number of violence risk prediction tools have been developed and introduced into clinical settings in North America. Among these, the Dangerous Behaviour Rating Scale (DBRS: Menzies et al, Reference Menzies, Webster and Sepejak1985a ,Reference Menzies, Webster, Sepejak, Webster, Ben-Aron and Hucker b ), the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG: Reference Harris, Rice and QuinseyHarris et al, 1993) and the HCR-20 (Reference Webster, Douglas and EavesWebster et al, 1997b ) have received most attention. The last two instruments contain an item assessing psychopathy, based on he Psychopathy Checklist (revised) (PCL-R; Reference HareHare, 1991). The PCL-R itself, however, has also been shown to have reasonable predictive validity in determining future violence, and will also be discussed in some detail.

Before describing these tools and their predictive validity it may be useful to describe one of the more recent statistical measures which is frequently cited in the literature on the accuracy of violence risk prediction.

Statistical measures for assessing predictive accuracy

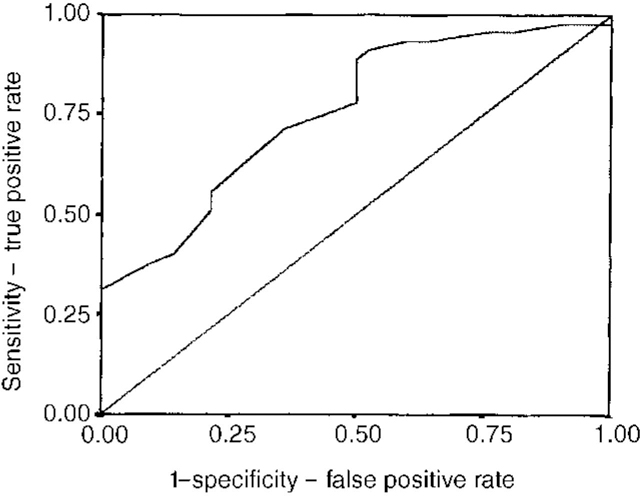

There are several measures available to evaluate the predictive accuracy of different tools in studies on violence risk prediction in large cohorts (see Appendix). Receiver operator characteristics (ROCs), which yield an area under the curve (AUC) measure, however, appear to be the preferred method, and much of the recent literature on predictive accuracy quotes ROC-AUC data. ROCs are particularly useful as they provide data which are fairly independent of the base rates of violence in a given population (Reference MossmanMossman, 1994). The ROC-AUC parameter, which can range from 0 to 1, provides information which is similar to that yielded by the more commonly used effect size estimate (such as Cohen's d; see Cohen, Reference Cohen1988; Reference Cohen1992) and can be used to compare accuracy between instruments. Figure 1 shows an example of a ROC curve. The straight line on the ROC curve corresponds to the line of no information, i.e. no better than random prediction (AUC=0.5). Instruments or clinicians which distinguish violent from non-violent patients with nearly perfect accuracy would have ROC-AUCs approaching 1.0. In general, Cohen's d> 0.50 or ROC-AUCs > 0.75 are considered large effect sizes. ROC curves also give an indication of the trade-offs between specificity and sensitivity at different decision thresholds or cut-off scores on measures.

Fig. 1 Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) for PCL-SV. Based on unpublished data available from the first author upon request. Straight line=area under curve (AUC) 0.5 (no greater than chance prediction); curved line indicates PCL-SV potential decision threshold/cut-off scores; AUC for PCL-SV=0.76, P <0.001.

CLINICAL RISK ASSESSMENT TOOLS AND THEIR PREDICTIVE VALIDITY

The Dangerous Behaviour Rating Scale (DBRS)

The DBRS (Reference Menzies, Webster and SepejakMenzies et al, 1985a ) was initially developed in conjunction with clinicians from a model devised by Megaree (Reference Megaree1976). The item list comprised 18 ratings of personality, situation, lifestyle-related variables, and interview-specific factors believed to relate to risk. Reports on the predictive validity of the DBRS, however, indicate that it has met with little success. For example, in Menzies and Webster's (Reference Menzies and Webster1995) 6-year follow-up study of 162 Canadian mentally disordered persons tracked across institutions and the community, comparatively little association was found between actuarial and clinical risk factors and follow-up violence outcome data. Professionals were no more accurate than non-clinical raters, and the DBRS items showed less predictive power than attributes such as age, violent history or employment status. The DBRS is now rarely used, and Webster et al (Reference Webster, Douglas, Eaves, Webster and Jackson1997a ) argue that the limitations of this instrument reflect the limited literature on which it was based.

The Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG)

The VRAG (Reference Harris, Rice and QuinseyHarris et al, 1993) incorporates 12 items, which are scored on the basis of a weighting procedure developed on a calibration sample of 618 males charged with severe violent crimes. The items are listed in Table 1. The variable with the heaviest weighting is the PCL-R score. Using ROCs, Rice & Harris (Reference Rice, Harris and Quinsey1995) analysed the data from several populations of offenders independent of the calibration sample, and found that the VRAG predicted violent recidivism with AUCs of 0.75, 0.74 and 0.74 for 3.5, 6 and 10 years, respectively. Using more restrictive definitions of violent recidivism, the relevant normalised ROC gave a mean AUC of 0.73. Later reports, however, suggest that the VRAG is less valuable in predicting violent sexual recidivism in paedophile sex offender populations (Reference Rice, Harris and QuinseyRice & Harris, 1997). The VRAG has been criticised because of its reliance on relatively static factors, and Webster et al (Reference Webster, Harris and Rice1994) now recommend that it be supplemented with a clinical checklist to produce a ‘violence prediction scheme’.

Table 1 Content lists for key risk prediction tools

| PCL-R (Reference HareHare, 1991) | PCL-SV (Reference Hart, Cox and HareHart et al, 1995) | HCR-201 (V2) (Reference Webster, Douglas and EavesWebster et al, 1997b ) | VRAG (Reference Harris, Rice and QuinseyHarris et al, 1993) | MacArthur VRAS (Reference Monahan, Steadman and AppelbaumMonahan et al, 2000) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors of community violence | Iterative classificatory tree | ||||

| 1 Glibness/superficial charm (1) | 1 Superficial (1) | H1 Previous violence | 1 PCL-SV score | Psychopathy (PCL-SV>12) | Seriousness of prior arrests |

| 2 Grandiose sense of self-worth (1) | 2 Grandiose (1) | H2 Young age at first violent incident | 2 Elementary school maladjustment | Number of adult arrests | |

| 3 Need for stimulation/proneness to boredom (2) | 3 Manipulative (1) | H3 Relationship instability | 3 DSM-III diagnosis of personality disorder | Substance misuse | Motor impulsiveness |

| 4 Lacks remorse (1) | H4 Employment problems | Anger | Father ever used drugs | ||

| 4 Pathological lying (1) | 5 Lacks empathy (1) | H5 Substance misuse problems | 4 Age at index offence | Father ever used drugs | Recent violent fantasies |

| 5 Conning/manipulative (1) | 6 Does not accept responsibility (1) | H6 Major mental illness | 5 Lived with both parents to age 16 | Father ever been arrested | Major disorder without substance misuse |

| 6 Lack of remorse or guilt (1) | H7 Psychopathy (PCL-R/PCL-SV) | 6 Failure on prior conditional release | Child abuse | ||

| 7 Shallow affect (1) | 7 Impulsive (2) | H8 Early maladjustment | 7 Non-violent offence score | Victim of child abuse | Legal status |

| 8 Callous/lack of sympathy (1) | 8 Poor behaviour controls (2) | H9 Personality disorder | 8 Marital status | Recent violent behaviour | Schizophrenia |

| 9 Parasitic lifestyle (2) | 9 Lacks (goals) (2) | H10 Prior supervision failure | 9 DSM-III diagnosis of schizophrenia | Violent fantasies | Anger reaction |

| 10 Poor behavioural controls (2) | 10 Irresponsible (2) | C1 Lack of insight | Employed | ||

| 11 Promiscuous sexual behaviour | 11 Adolescent antisocial behaviour (2) | C2 Negative attitudes | 10 Victim injury (index offence) | Recent violence | |

| 12 Early behavioural problems (2) | C3 Active symptoms of major mental illness | 11 History of alcohol misuse | Loss of conscience | ||

| 13 Lack of realistic long-term goals (2) | 12 Adult antisocial behaviour (2) | 12 Female victim (index offence) | Parents fought | ||

| 14 Impulsivity (2) | C4 Impulsivity | ||||

| 15 Irresponsibility (2) | C5 Unresponsive to treatment | ||||

| 16 Failure to accept responsibility | R1 Plans lack feasibility | ||||

| 17 Many short-term marital relationships | R2 Exposure to destabilisers | ||||

| R3 Lack of personal support | |||||

| 18 Juvenile delinquency (2) | R4 Non-compliance with remediation attempts | ||||

| 19 Revocation of conditional release (2) | R5 Stress | ||||

| 20 Criminal versatility | |||||

Psychopathy Checklist (Revised) (PCL-R)

The 20-item PCL-R (Reference HareHare, 1991), which is scored on a three-point scale, was originally devised as a research tool for operationalising psychopathy (see Table 1). Scores range from 0 to 40, with a cut-off of > 30 reflecting a prototypical psychopath. The PCL-R has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Reference Cooke, Cooke, Forth and HareCooke, 1998). It has a stable factor structure (Reference HareHare, 1991), in which factor 1 taps interpersonal/affective traits, while factor 2 reflects the behavioural components of psychopathy. Cooke & Mitchie (Reference Cooke and Mitchie1998), however, have recently presented a three-factor model of psychopathy using confirmatory factor analytic procedures. A number of studies demonstrate its utility as a risk assessment tool, in identifying recidivists and predicting violence in North American forensic and prison samples (Reference Hart, Cooke, Forth and HareHart, 1998a ). As yet, there are few data on its predictive validity in European samples, although recent work by Grann et al (Reference Grann, Langstrom and Tengstrom1999) suggests that the PCL-R scores were the best predictor of violent recidivism 2 years after release from containment in Swedish offenders with personality disorder (AUC=0.72).

The PCL-R has been supplemented by the 12-item screening version (PCL-SV: Reference Hart, Cox and HareHart et al, 1995) (Table 1). It has similar psychometric properties to the PCL-R, with scores ranging from 0-24 (cut-off at 18). The PCL-SV has been shown to have good predictive validity for institutional violence (Reference Hill, Rogers and BickfordHill et al, 1996; Reference GrannGrann, 1998) and community violence (MacArthur study, Reference Monahan, Steadman and AppelbaumMonahan et al, 2000).

As some psychopathy checklist items may be linked to outcome variables of interest (such as violence), researchers have used different methods to control for this potential confounder, including statistical control for past criminal activity or removing potentially confounding items from the checklist in the analysis.

The Historical/Clinical/Risk Management 20-item (HCR-20) scale

The HCR-20 (Reference Webster, Douglas and EavesWebster et al, 1997b ) contains 10 historical (H-10) items (two of which address the issue of personality dysfunction), five clinical (C-5) items, and five risk management (R-5) items (Table 1). It is scored in a similar manner to the PCL-R and shows good interrater reliability (Reference Webster, Douglas, Eaves, Webster and JacksonWebster et al, 1997a ). When the personality disorder variable is removed, H-10 items show significant correlations with on-ward violence (unpublished, 1996; details available from the first author upon request). In two studies, the H-10 items showed stronger correlations with violent outcome than the C-5 scales (see Reference DouglasDouglas, 1996; unpublished, 1996); this may reflect the lack of inclusion of interview data in these retrospective studies.

Table 2 lists some key HCR-20 studies examining the predictive validity using ROC-AUC data. While the studies are limited to a small group of North American researchers, the data generally show ‘better than chance’ relationships between HCR-20 scores and violent outcomes. As yet, no studies have been published of the reliability and validity of this instrument in UK samples, although such work is in progress (details available from the first author upon request).

Table 2 HCR-20 risk predictive validity studies

| Author | Patient sample | Measures | Outcomes | Instrument | ROC-AUCs | Instrument | ROC-AUCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douglas et al (Reference Douglas, Ogloff and Nicholls1999) | Non-forensic psychiatric | Community violence | Violent crime | HCR-20 | 0.80 | PCL-SV | 0.78 |

| Any violence | HCR-20 | 0.76 | PCL-SV | 0.68 | |||

| Physical violence | HCR-20 | 0.76 | PCL-SV | 0.73 | |||

| Nicholls et al (Reference Nicholls, Douglas and Ogloff1997) | Non-forensic psychiatric | Community violence (males) | Any violence | HCR-20 | 0.74 | ||

| Violent arrest | HCR-20 | 0.78 | |||||

| Community violence (females) | Any violence | HCR-20 | 0.63 | ||||

| Violent arrest | HCR-20 | 0.77 | |||||

| Unpublished (1998a)1 | Civil psychiatric patients | Community violence | Any violence | HCR-20 | 0.67 | PCL-SV | 0.65 |

| Violent arrest | HCR-20 | 0.75 | PCL-SV | 0.70 | |||

| Grann (Reference Grann1998) | Forensic | Community violence | Violence in personality disorder & people with schizophrenia | H scale | 0.71 | VRAG | 0.63 |

| H scale | 0.66 | VRAG | 0.60 | ||||

| Unpublished (1997)1 | Non-forensic psychiatric | In-patient violence | Physical & non-physical | H/C scales | 0.57-0.65 | PCL-SV | 0.60-0.64 |

| Unpublished (1998b)1 | Non-forensic psychiatric | In-patient violence | Any type of aggression | H/C scales | 0.63 | PCL-SV | 0.61 |

| H/C scales | 0.68 |

Comparison of actuarial risk scales

The PCL/PCL-R has generally been found to be superior to other classical actuarial risk scales on indices of recidivism or violent recidivism (Reference Harris, Rice and QuinseyHarris et al, 1993; Reference Rice, Harris and QuinseyRice & Harris, 1995; Reference Zamble, Palmer, Cooke, Forth and NewmanZamble & Palmer, 1996; see also Reference Hemphill, Hare and WongHemphill et al, 1998). Rice and Harris (Reference Rice, Harris and Quinsey1995) compared the SIR scale and VRAG, and found significantly better prediction rates with the VRAG, although the SIR scale (contrary to initial perceptions: Reference NuffieldNuffield, 1982) also showed reasonable ROC-AUCs (0.69, 0.67 and 0.66 at 3.5-, 6- and 10-year follow-up). Zamble and Palmer (Reference Zamble, Palmer, Cooke, Forth and Newman1996) compared the PCL-R, parole board decisions and the SIR scale, in 106 male offenders released from Canadian federal penitentiaries and found the PCL-R to be the most accurate at predicting reconviction or revocation of parole at a mean followup time of 30 months. Hemphill and Hare (Reference Hemphill, Hare, Cooke, Forth and Newman1996) also compared the predictive validity of the PCL/PCL-R and several actuarial measures, and found that they performed similarly for general recidivism prediction, but that the PCL-R was significantly better for violent recidivism prediction.

Using ROCs, Grann (Reference Grann1998) compared the H-10 scale of the HCR-20 and VRAG in predicting reconviction for violence within 2 years of release, in a retrospective study of 293 violent offenders with personality disorders and 111 with schizophrenia. He reported that both scales performed better in the personality-disorder group but the H-10 did better than the VRAG in both groups of offenders. It is possible that historical/static variables may be relatively good predictors of violent recidivism in subjects with personality disorder, but clinical and risk management variables may be better predictors in populations with schizophrenia (Reference Webster, Douglas, Eaves, Webster and JacksonWebster et al, 1997a ; Reference GrannGrann, 1998; Reference Strand, Belfrage and FranssonStrand et al, 1999).

General reviews and meta-analysis of studies of violence and recidivism

There have been four relatively recent meta-analytic studies of recidivism, including violent recidivism, and each differs in the studies included in it and the method of effect size determination.

Mossman (Reference Mossman1994) extracted 58 data sets from 44 published studies dating from 1972 to 1993 on violence risk prediction, and examined prediction accuracy using ROCs. The studies included a broad range of subjects, settings, population sizes and clinical criteria for assessing violence, and Mossman acknowledges that conclusions can only be tentative. The median ROC-AUCs for all 58 data sets was 0.73, suggesting, overall, that clinicians were predicting violence more accurately than chance. However, short-term (1-7 days, AUC=0.68) predictions were no more accurate than long-term (> 12 months, AUC=0.64). First-generation studies (before 1986) (AUC=0.74) were less accurate than second-generation studies (after 1986) (mean AUC=0.83), but the samples were extremely heterogeneous. Mossman suggests that clinicians were able to distinguish violent from non-violent patients with a “modest, better than chance level of accuracy”. Since this work was published, other reviews have concentrated on the issue of recidivism, particularly violent recidivism, which is generally perceived as a ‘harder’ outcome measure.

Bonta et al (Reference Bonta, Hanson and Law1998) conducted a meta-analysis of predictive longitudinal studies (1959-1995), to examine whether predictors of recidivism, including violent recidivism, for mentally disordered offenders were different from those for non-disordered offenders. Using 64 separate samples with 27 predictors for violent recidivism, they showed that criminal history variables were better predictors than clinical variables, using adjusted and transformed Pearson's correlations to assess effect size (Zr). For violent recidivism, criminal history variables had the largest effect size (Zr=0.15, P <0.001), followed by personal demographics (Zr=0.12, P <0.001), deviant lifestyle (Zr=0.08, P <0.001) and clinical variables (Zr=-0.03, P <0.01). A diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder was the most significant clinical predictor.

Role of the PCL/PCL-R and PCL-SV in risk prediction

The PCL-R and PCL-SV are currently believed be some of the most reliable tools for assessing personality constructs likely to be relevant to violent risk prediction (Reference HartHart, 1998b ). For this reason the PCL-SV was included in the MacArthur VRAS, where it was shown to have reasonable predictive validity for community violence (Reference Monahan, Steadman and AppelbaumMonahan et al, 2000). Hemphill & Hare (Reference Hemphill, Hare, Cooke, Forth and Newman1996) have also shown that the PCL/PCL-R, entered into a hierarchical multiple regression analysis with other demographic/clinical history variables, adds significant incremental validity to the prediction of violence.

Meta-analytic studies using the PCL/PCL-R/PCL-SV in risk prediction

Salekin et al (Reference Salekin, Rogers and Sewell1996) examined all 18 available (published and unpublished) studies using the PCL/PCL-R between 1974 and 1995 and conducted a meta-analytic review, using an adaptation for effect size calculation from Rosenthal (Reference Rosenthal1991). Separate analyses were conducted for violent recidivism. Despite the variation in cut-off scores on these instruments, Salekin et al (Reference Salekin, Rogers and Sewell1996) reported moderate to strong effect sizes (Cohen's d=0.55 for criminality, r=0.37 and d=0.79 for violent recidivism; see Table 3). The largest effect sizes were reported in the study of institution violence by Hill et al (Reference Hill, Rogers and Bickford1996) using the PCL-SV. Although the study by Salekin et al (Reference Salekin, Rogers and Sewell1996) included a small number of postdictive studies (comparing assessment measures with previous violence) which may have inflated their reported mean effect sizes, they found no significant difference between postdictive (0.75) and predictive (0.79) effect sizes, on a separate analysis.

Table 3 Studies utilising Psychopathy Checklists (PCLs) to predict violent behaviour

| Study | Version | Sample | Validity | Outcome | Effect size (ES) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salekin et al (Reference Salekin, Rogers and Sewell1996) review | r =0.37 | ||||

| d =0.80 | |||||

| Forth et al ( Reference Forth, Hart and Hare1990)1 | PCL | Maximum security youth detention centre | Postdiction | Violent recidivism | d=0.56 |

| Forth et al ( Reference Forth, Hart and Hare1990)1 | PCL | Maximum security youth detention centre | Prediction | Violent recidivism | d=0.54 |

| Forth et al ( Reference Forth, Hart and Hare1990)1 | PCL | Maximum security youth detention centre | Postdiction | Institutional violence and/or aggression | d=1.04 |

| Hare & McPherson ( Reference Hare and McPherson1984)1 | PCL | Federal medium security prison | Postdiction | Violent recidivism | d=0.54 |

| Harris et al ( Reference Harris, Rice and Cormier1991)1 | PCI | Therapeutic community programme | Prediction | Violent recidivism | d=0.93 |

| Heilbrun et al ( Reference Heilbrun, Hart and Hare1998)1 | PCL | Forensic psychiatric patients | Prediction | Institutional violence and/or aggression | d=0.63 |

| Hill et al ( Reference Hill, Rogers and Bickford1996)1 | PCL-SV | Forensic psychiatric patients | Prediction | Institutional violence and/or aggression | d=1.92 |

| Kosson et al ( Reference Kosson, Smith and Newman1990)1 | PCL-R | Maximum security youth detention centre | Postdiction | Violent recidivism | d=0.42 |

| Miller et al (1994)1 | PCL-R | Forensic treatment centre for sexual offenders | Postdiction | Violent recidivism | d=1.18 |

| Quinsey et al ( Reference Quinsey, Rice and Harris1995)1 | PCL-R | Forensic treatment centre for sexual offenders | Prediction | Violent recidivism | d=0.7 |

| Rice & Harris ( Reference Rice, Harris and Quinsey1992)1 | PCL | Forensic psychiatric patients | Prediction | Violent recidivism | d=0.54 |

| Unpublished (1992)3 | PCL-R | Therapeutic community programme | Prediction | Violent recidivism | d=0.72 |

| Rice et al ( Reference Rice, Harris and Quinsey1990)1 | PCL | Forensic treatment centre for sexual offenders | Prediction | Violent recidivism | d=0.74 |

| Serin (Reference Serin1991) | PCL | Federal medium security prison | Postdiction | Violent recidivism | d=0.74 |

| Serin & Amos ( Reference Serin and Amos1995)1 , 2 | PCL-R | Federal medium security prison | Prediction | Violent recidivism | d=0.58 |

| Hemphill et al (Reference Hemphill, Hare and Wong1998) review | r =0.27 | ||||

| d =0.56 | |||||

| Hemphill et al (1992)2 | PCL | Criminal psychopaths | Prediction | Violent recidivism | r=0.06 |

| Harris et al ( Reference Harris, Rice and Quinsey1993)2 | PCL | Forensic psychiatric patients | Prediction | Violent recidivism | r=0.34 |

| Heilbrun et al ( Reference Heilbrun, Hart and Hare1998)2 | PCL | Forensic psychiatric patients | Prediction | Violent recidivism | r=0.16 |

| Ross et al (1992)2 | PCL | French prison parolees | Prediction | Violent recidivism | r=0.17 |

| Serin & Amos ( Reference Serin and Amos1995)1 , 2 | PCL-R | Federal medium security prison | Prediction | Violent recidivism | r=0.28 |

| Studies outside North America | |||||

| Grann et al (Reference Grann, Langstrom and Tengstrom1999) | PCL-R | Forensic psychiatric evaluations (prison, hospital and probation) | Prediction | Violent recidivism | AUC of ROC at 2 years=0.75 |

| Unpublished (1999)3 | PCL-SV | Medium security forensic | Prediction | In-patient violence | AUC of ROC at 3 months=0.75 |

Hemphill et al (Reference Hemphill, Hare and Wong1998) also conducted a meta-analysis of PCL/PCL-R studies in prediction of general/violent recidivism, but included only predictive studies and those with independent samples. The 1996 review by Salekin et al had included several same sample studies from the Oak Ridge group. Based on the five studies shown in Table 3 (1374 offenders) and more restrictive criteria, Hemphill et al (Reference Hemphill, Hare and Wong1998) reported a slightly lower mean effect size for violent recidivism (r=0.27, Cohen's d=0.56). Overall the predictive validity of the PCL-R is moderately high (Reference Hart, Cooke, Forth and HareHart, 1998a ).

PUTTING SYSTEMATIC RISK ASSESSMENT INTO PRACTICE

Gardner et al (Reference Gardner, Lidz and Mulvey1996) suggest that clinicians may be averse to actuarial or structured clinical prediction instruments because they are impractical and too costly, and the analyses too complex. They developed a ‘regression tree’ (i.e. structured sequences of yes/no answers that lead to classification of a case as high or low risk) and a two-stage screening process, which they showed was as accurate as traditional actuarial measures. Monahan et al (Reference Monahan, Steadman and Appelbaum2000) also developed an Iterative Classification Tree (ICT) which successfully classified 77.6% of their sample as high or low risk, based on the variables shown in Table 2. ROCs for the ICT method were high (AUC=0.82). In higher risk cases, Serin and Amos (Reference Serin and Amos1995) suggest a three-stage decision tree, which includes an analysis of ‘group base rates’ of violence, ‘individual base rate risk’ and ‘risk management variables’.

Decision or classification trees appear to be a useful means of streamlining violence risk assessments in large populations with relatively low base rates of violence. In smaller samples of high-risk patients or offenders, however, more indepth batteries of relevant tools such as the PCL-R and HCR-20 will be required to assess future risk of violent recidivism.

SUMMARY

This review indicates that structured clinical judgement and systematic risk assessment scales should be used cautiously and judiciously. The assessment tools chosen, and how to interpret the scores, will largely be influenced by the populations or settings and the questions we want answered. The MacArthur project group have developed a classificatory tree method for assessing risk in community samples. For clinicians working in forensic or penal settings, much can be learned from the studies demonstrating the predictive accuracy of tools such as the PCL-R and HCR-20. Future British studies should aim to establish the validity of North American risk assessment tools in a range of populations and settings. Efforts should also be made to enhance the predictive validity of these tools by the addition of physiological measures and assessments of neurocognitive function and how individuals process emotional information. Violence prediction will never be entirely accurate, given that violence itself is a complex concept. Clinicians need to be aware of the benefits and limitations of current assessment tools and how scores on these measures might be used or interpreted by other agencies (see Hare (Reference Hare1998) for a commentary on the use and misuse of the PCL-R).

APPENDIX - TERMINOLOGY

True positive, TP=predicted risk, outcome violent

False positive, FP=predicted risk, outcome not violent

False negative, FN=predicted no risk, outcome violent

True negative, TN=predicted no risk, outcome not violent

Base rate, BR=(TP+FN)/(TP+FP+FN+TN)=(proportion of violent individuals in a population)

Selection ratio, SR=(TP+FP)/(TP+FP+FN+TN) =(cut-off scores used to classify individuals as violent)

Correctfraction, CF=(TP+TN)/(TP+FP+FN+TN)

Sensitivity=true positive rate, TPR=TP/(TP+FN)

Specificity=true negative rate, TNR=TN/(TN+FP)

Positive predictive power=Proportion of individuals designated a risk who in fact are a risk

Negative predictive power=Proportion of individuals identified as low risk and who in fact are low risk

False positive rate, FPR=(1-specificity)=FP/(FP+TN)

Risk ratio=TPR/FPR

Odds ratio=(TP.TN)/(FP.FN)=odds that person predicted to fail will do so/odds a person not predicted to fail will do so

Relative improvement over chance, RIOC=CF - ((BR)(SR)+(1-BR)(1-SR))

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Structured/systematic approaches to violence risk prediction provide a more accurate and transparent record of the risk factors considered and the rationale behind decisions taken.

-

▪ Risk assessment batteries need to be streamlined and adapted to suit the population under study and the key questions asked.

-

▪ The Psychopathy Checklist and its derivatives appear to be significant predictors of violence in forensic and non-forensic settings.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ There are a limited number of studies on the reliability and validity of published risk assessment tools outside the centres in which they were developed.

-

▪ The literature on accuracy of violence risk is predominately postdictive rather than predictive, and much needs to be done to improve current violence prediction accuracy, using prospective study designs.

-

▪ The lack of uniformity in the statistical procedures used to assess predictive accuracy, and the variation in choice of cut-off scores on risk prediction tools, make comparisons between studies difficult. The reporting of receiver operator characteristic data should improve this situation.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.