Introduction

Interactions between suckerfish (Echeneidae; Gray et al., Reference Gray, McDowell, Collette and Graves2009) and other marine vertebrates (cetaceans, sirenians, turtles, teleost fish and elasmobranchs) are frequently observed around the world and commonly considered a type of commensalism (Sazima et al., Reference Sazima, Moura and Rodrigues1999; Fertl et al., Reference Fertl, Landry and Barros2002; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Mignucci-Giannoni, Bunkley-Williams, Bonde, Self-Sullivan, Preen and Cockcroft2003). Particularly for sea turtles, it has already been described as phoresis (i.e. ‘hitchhiking’, Williams et al., Reference Williams, Mignucci-Giannoni, Bunkley-Williams, Bonde, Self-Sullivan, Preen and Cockcroft2003; Sazima & Grossman, Reference Sazima and Grossman2006; Bachman et al., Reference Bachman, Kraus, Peterson, Grubbs and Peters2018). Suckerfish associations with sharks of the family Carcharhinidae were recognized to have a potential negative nature (Ritter, Reference Ritter2002) and Brunnschweiler (Reference Brunnschweiler2006) went further to suggest it can be a parasite–host relationship. In Brazil, cetacean-suckerfish associations and interactions have been observed for humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae (Wedekin et al., Reference Wedekin, Freitas, Engel and Sazima2004), for bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus (CLS Sampaio, pers. obs.), spinner dolphins Stenella longirostris (Silva & Sazima, Reference Silva and Sazima2003), and only one case of association with an adult Guiana dolphin Sotalia guianensis, in Cananéia Estuary, south-east Brazil (Santos & Sazima, Reference Santos and Sazima2005). Additionally, Wedekin et al. (Reference Wedekin, Freitas, Engel and Sazima2004) described a rough-toothed dolphin Steno bredanensis preying on an echeneid in the eastern Brazilian coast. The record was made while researchers followed humpback whales in the Abrolhos Bank (16°40′S 038°50′W), and the fish was likely attached to one of the whales before being preyed. Since records of suckerfishes associated with marine mammals in Brazilian coastal waters are rare, the nature of the ecological interactions between suckerfish and dolphins in the area remains poorly understood. The sharksucker Echeneis naucrates is known to be widely distributed in Brazilian waters (Carvalho-Filho, Reference Carvalho-Filho1999; Sampaio & Nottingham, Reference Sampaio and Nottingham2008) and, although not frequently observed in the area, it has already been registered for Baía de Todos os Santos, a tropical bay with calm waters in the state of Bahia, north-eastern Brazil, where the present record was made (Andrade, Reference Andrade2007; Lopes et al., Reference Lopes, Oliveira-Silva, Souza, Kieronski and Oliveira2007). This work reports the first observation of a sharksucker associated with a young, rather than adult, Guiana dolphin, and for the first time, on the tropical coast of Brazil. We also hypothesize and discuss a novel case of host-fidelity for sharksuckers.

Materials and methods

The Guiana dolphin population inhabiting Baía de Todos os Santos (BTS; Figure 1) has been regularly monitored since 2010, with focal-follow methods from small boats. In early December 2012 and mid-January 2013, while searching for dolphins in the estuary of Paraguaçú River, north portion of the bay (12°51′S 38°49′W), the same group of Guiana dolphins was photographed while foraging (Figure 2). A sharksucker was observed and photographed attached to a young (i.e. small body size) dolphin on both occasions. Photos were examined and compared against bibliographic records for species identification (Carvalho-Filho, Reference Carvalho-Filho1999; Santos & Sazima, Reference Santos and Sazima2005; Sampaio & Nottingham, Reference Sampaio and Nottingham2008; Robertson & Van Tassell, Reference Robertson and Van Tassell2019), and the record included in the database of Bio.Conserve Consultoria Ambiental, the NGO conducting the monthly monitoring.

Fig. 1. Study area, indicating where observations were made (black triangle), at the Paraguaçú River mouth, Baía de Todos os Santos (12°51′S 38°49′W). The Cananéia estuary (black circle) is shown for reference.

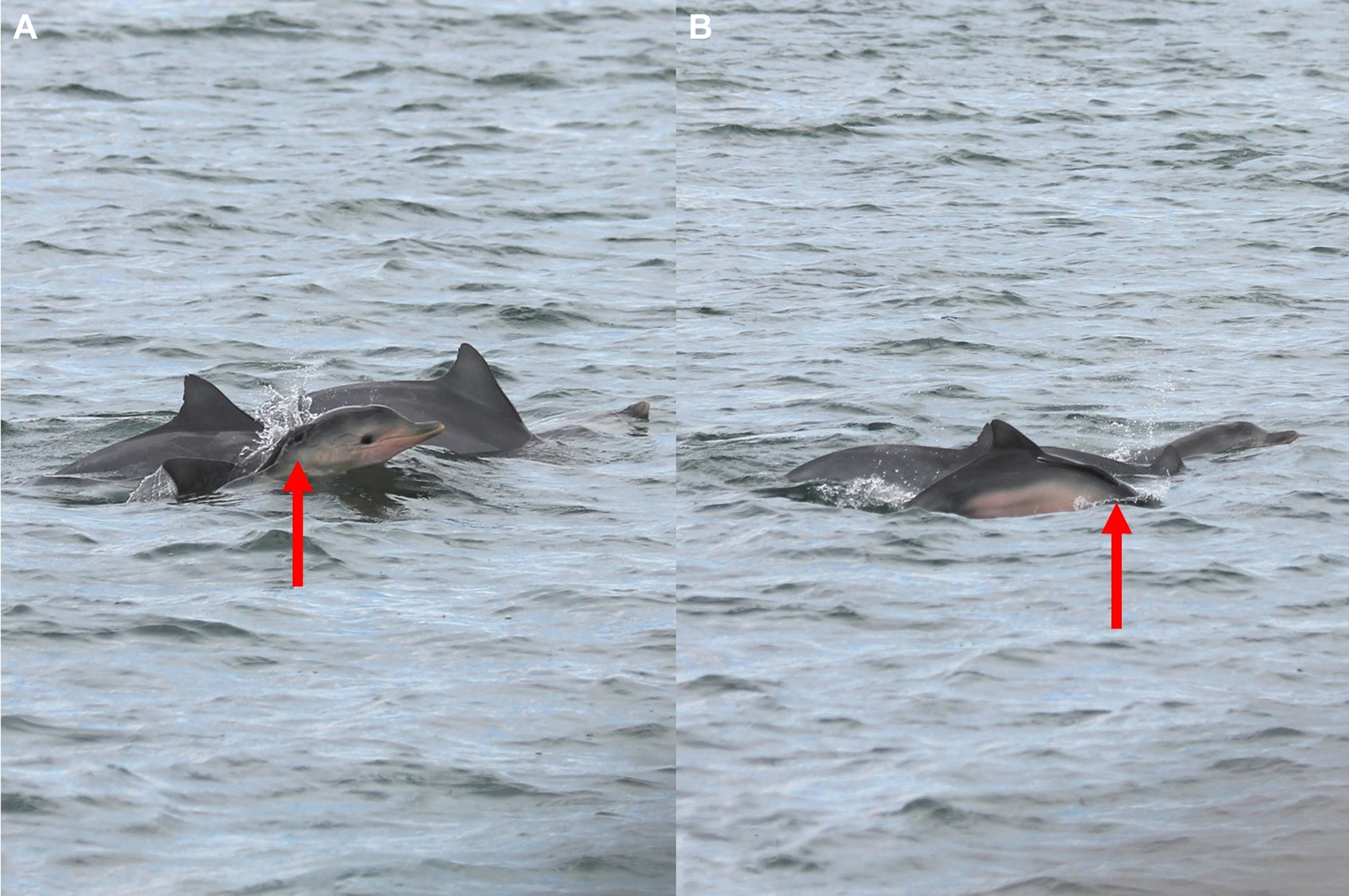

Fig. 2. Juvenile Guiana dolphin with a sharksucker attached to its dorsal portion during traveling behaviour (A) and during an aerial behaviour (B), on 2 December 2012. Red arrows indicate the sharksucker. (Photos: TEW Ross).

Results and discussion

The first observation was made on 2 December 2012, at noon, when a group of seven adults and one juvenile Guiana dolphin were detected. The juvenile had a sharksucker attached to its dorsal region (Figure 2).

The second record was made 47 days later, on 18 January 2013, when the same juvenile dolphin was recognized as part of a seven-animal group. Again, that dolphin was observed with a sharksucker attached to the same region of its body as during the first observation (Figure 3). The identification of the young dolphin was possible since it was closely associated with an adult on both occasions, likely its mother. The adult dolphin is a known female previously registered in the photo-identification catalogue of dolphins in the BTS (i.e. dolphin BFC#45).

Fig. 3. Second encounter of a juvenile Guiana dolphin, 47 days after the first encounter. What appears to be the same sharksucker was attached to its body. Red arrows indicate the sharksucker. (Photos: LRA Souto).

The sharksucker was identified as Echeneis naucrates (CSL Sampaio, pers. obs.) using morphological characteristics (e.g. elongated body) and colour (i.e. black with clear line along the sides of the body, and the tips of dorsal, anal and caudal fins narrowly white; see Sampaio & Nottingham, Reference Sampaio and Nottingham2008; Robertson & Van Tassell, Reference Robertson and Van Tassell2019) and its known presence in the region (Andrade, Reference Andrade2007; Lopes et al., Reference Lopes, Oliveira-Silva, Souza, Kieronski and Oliveira2007). Despite a closer examination of the specimen not being possible (i.e. the sharksucker was not collected), the observations made in the field and photos leave no doubt that the fish is in fact E. naucrates, and not a related species which does not occur in the area (CSL Sampaio, pers. obs.). Long-term studies and monitoring of S. guianensis in the BTS have been done for more than 10 years; still, the present association had never been observed (Spínola, Reference Spínola2006; Batista, Reference Batista2008). No apparent behavioural signs indicating stress or irritation of the dolphin (Weihs et al., Reference Weihs, Fish and Nicastro2007; Silva & Sazima, Reference Silva and Sazima2008) were observed.

The findings described here support the hypothesis that the sharksucker attached to the juvenile dolphin was the same individual in both cases (i.e. it was attached to the same body region, in the same dolphin). Very little is known about host fidelity for E. naucrates, and in fact for suckerfish species in general. Brunnschweiler et al. (Reference Brunnschweiler, Vignaud, Côté and Maljković2020) present evidence of skin injury caused by a sharksucker attached to a blubberlip snapper Lutjanus rivulatus for a year. Furthermore, a whalesucker Remora australis was observed while attached to a spinner dolphin for a period similar to that observed here (about 1.5 months; Silva & Sazima, Reference Silva and Sazima2003).

For the entire distribution range of S. guianensis, a similar association was only described in an estuary region in south-eastern Brazil, and for an adult Guiana dolphin (Santos & Sazima, Reference Santos and Sazima2005). Although this is possibly the most studied cetacean species in Brazil, due to its high frequency of strandings (Di Beneditto & Rosas, Reference Di Beneditto, Rosas, Monteiro-Filho and Monteiro2003), wide distribution along coastal areas (Flores & Da Silva, Reference Flores, Da Silva, Perrin, Würsig and Thewissen2009) and stranding networks effort all along the Brazilian coast, little is known about its interactions with other marine species. The present work is the first record of this association to the north-eastern region of the country. More information is needed to understand if such an interaction is a frequent event and if it is prevalent on younger dolphins and/or suckerfish. Understanding the nature of associations between suckerfish and Guiana dolphins may elucidate important ecological aspects of both species.

Data

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Adalberto Lúcio Portela Neto, Priscila N. Malafaia and Daniel S. Brasil de Souza, staff of Bio.Conserve Consultoria Ambiental Ltda, for their assistance on the monitoring of Guiana dolphin population at Paraguaçú River. Ivan Sazima provided critical idea inputs to this study. Biomonitoramento Ambiental Ltda provided logistical support during the data collection. Two anonymous reviewers provided important suggestions to improve this manuscript.

Author contributions

L.R.A.S. and M.S.S.R. secured funding for fieldwork. L.R.A.S., T.E.W.R. and M.S.S.R. collected the data. C.L.S.S. identified the fish species. L.R.A.S. and G.A.B. were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

Fieldwork activities were funded by BioMonitoramento Ambiental Ltda. GA Bortolotto was funded by CNPq (PhD scholarship #208203/2014-1) during their contribution to this study. The funders were not involved in designing the study, in the data collection, analysis and interpretation, and in the writing of this manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical standards and consent to participate

Not applicable.