1. Introduction

Austerity measures introduced in the aftermath of the financial crisis have pushed fiscal policy to the forefront of the political agenda and public debate. As the post-crisis situation has shown, governments vary in their ability to implement the necessary cuts to public spending and control fiscal policy more generally. One of the proposed mechanisms to increase control over fiscal policy is to delegate the oversight of the budgeting process to a minister for finance (Hallerberg, Reference Hallerberg2004). We know that this mechanism is particularly effective when appropriate budgetary rules are in place (Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2013) and when finance ministers are supported by their prime ministers in the budgeting process (Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen, Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009, 36). The budgetary process is often characterized as struggle for power, with budgetary decisions being about the distribution of power expressed through fiscal means (e.g., Wildavsky and Caiden, Reference Wildavsky and Caiden2004). During times of plenty, the core executive maintains sufficient resources to dampen any political conflicts. This, however, becomes increasingly difficult during times of austerity when all budgets face cuts. How does fiscal austerity affect the relationship between intra-cabinet budgetary politics and fiscal governance?

We address this question by assessing the preferences of cabinet ministers over budgetary allocation decisions made by the prime minister and minister for finance. There is very little empirical work on preference heterogeneity in cabinet governments. Traditionally, this has been due to the lack of objective information on cabinet decision-making. This is partly a result of the concept of collective responsibility whereby cabinet discussions and potential disagreements remain confidential in order for the cabinet to appear united in public (James, Reference James2002, 7). Available empirical data appears only in political memoirs (e.g., Mendelson, Reference Mendelson2010; Richards and Mathers, Reference Richards and Mathers2010; Bevir and Rhodes, Reference Bevir and Rhodes2006) or occasional leaks (e.g., Rawnsley, Reference Rawnsley2010; Leahy, Reference Leahy2009, Reference Leahy2013). All of this makes cabinets appear empirically as a ‘black box’ that has only recently begun to be systematically opened up due to advances in text analysis (e.g., Giannetti and Laver, Reference Giannetti and Laver2005).

Analyzing the speeches of cabinet ministers delivered during budget debates allows us to identify ministers' preferences over the allocation of government spending across departments and test the micro-mechanism of fiscal decision-making. This allows us to make two important contributions to the literature. First, we replicate a key finding by Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen (Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009) that spending decisions will reflect the preferences of the finance minister under fiscal delegation, but we do so at the level of individual ministers rather than using party-level preference measures. As a result, we can study fiscal delegation in a context in which the prime minister and finance minister are from the same party. Second, we offer a novel hypothesis that the effectiveness of fiscal delegation is conditional on external events that affect the macroeconomic environment (in our case a severe economic crisis), with an increase in competition between the prime minister and finance minister triggered by the external event leading to a breakdown of the delegation mechanism.

Our empirical case study is Ireland which has a well-documented history of intra-cabinet political competition, with varying intensity over time. Since 1998 the country has also implemented the delegation mechanism of fiscal governance (Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen, Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009, 50), along with a very robust fiscal governance and control process in comparison to other EU member states (Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen, Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009, 74). By looking at Ireland for the period since 1999—from boom to bust—we are able to trace how the relationship between intra-cabinet competition and fiscal governance changes with the external economic environment.

In contrast to previous results in the literature, we find that the delegation mechanism has varying performance over the economic cycle. Under the delegation mechanism the finance minister has significant discretion in budgetary decision-making. We show that cabinet ministers closer to the finance minister on our estimated dimension of intra-cabinet competition receive greater increases in budget shares. This discretionary power fits with theoretical predictions of the delegation mechanism employed in fiscal governance. However, we also find that during economic crisis the prime minister can intercede on behalf of those ministers closest to him and alleviate cuts to their departments, thus curtailing the finance minister's discretionary power and potentially hindering the intended performance of the delegation mechanism.

2. Intra-cabinet politics of budgetary process

The involvement of cabinet ministers in collective decision-making is one of the potential causes of intra-cabinet conflict. This may derive from the representation of distinct and conflicting interests and also from overlapping jurisdictions, particularly in the case of the finance minister (Andeweg, Reference Andeweg2000). Most, if not all, departmental proposals have budgetary consequences which brings the spending needs of individual departments into direct confrontation with the finance minister who often has veto power over spending proposals.

From a fiscal policy perspective, preference heterogeneity in the cabinet contributes to the so-called common pool problem. Taxes drawn from the larger population fund expenditure programs targeting narrow interest groups (Von Hagen and Harden, Reference Von Hagen and Harden1995). This creates a difference in benefits between the larger group of taxpayers and the smaller group of program recipients, bringing with it an abundance of possibilities to free ride. Representatives of interest groups receiving targeted spending have an incentive to overspend compared to socially-optimal levels. The common pool problem has been shown to result in larger government debts and excessive deficits (Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen, Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009; Velasco, Reference Velasco2000) and, more generally, in economically inefficient policies (Weingast, Shepsle and Johnsen, Reference Weingast, Shepsle and Johnsen1981). In parliamentary systems, the number of parties in government (Bawn and Rosenbluth, Reference Bawn and Rosenbluth2006) and the number of spending ministers (Schaltegger and Feld, Reference Schaltegger and Feld2009; Wehner, Reference Wehner2010) leads to higher spending and budget deficits.

One possibility to solve the collective action problem is to appoint an ‘entrepreneur’ with sufficient powers to induce and monitor coordination between all actors. Among the ministers in the cabinet, the minister for finance (or equivalent) usually plays the role of such a fiscal entrepreneur (Hallerberg, Reference Hallerberg2004). The delegation of powers over budgetary decision-making to the finance minister as fiscal entrepreneur results in the centralization of the budgetary process. Empirical results show that centralization can reduce the effect of the overspending bias resulting from the common pool problem (de Haan, Jong-A-Pin and Mierau, Reference de Haan, Jong-A-Pin and Mierau2013; Hallerberg, Reference Hallerberg2004). More recently, Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2013) have shown that this is particularly effective when other fiscal rules are in place that reduce the incentives and abilities of coalition members to increase spending.

The preferences of the fiscal entrepreneur are assumed to be aligned with society at large, with the functional goal of maximizing social welfare. Alesina and Perotti (Reference Alesina, Perotti, Poterba and von Hagen1999, 23) suggest that the constituency of spending ministers are interest groups benefiting from certain programs, while the constituency of the finance minister is the average taxpayer. Spending ministers are often evaluated on their ability to protect the interests of their departmental constituency. An example is the German Defense Minister, Hans Apel, in the Helmut Schmidt cabinet, a working-class Social Democrat who became an ardent defender of his ministry and was one of two Social Democrats in the Bundestag to vote in favor of stationing US short-range missiles in Germany (Hallerberg, Reference Hallerberg2004, 24). Representing the average taxpayer gives the finance ministry an incentive to internalize the aggregate costs of spending programs, while spending departments do not have an incentive to do so.

The downside of delegating fiscal authority to a strong finance minister is that spending decisions could be biased toward the minister's own policy preferences. It is rare in parliamentary systems that non-partisan external experts are appointed to cabinet positions. Instead, finance ministers are usually recruited from the top ranks of their parties. They therefore naturally favor some constituencies over others, either for electoral reasons, career ambitions, or simply because of their individual political beliefs. Delegation of fiscal authority is therefore a trade-off between counter-balancing the overspending biases of individual ministers and the bias induced by a partisan finance minister (Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen, Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009). This observation can be summarized as our first hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1

If a delegation mechanism is in place, spending decisions will reflect the policy preferences of the finance minister.

Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen (Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009) have provided empirical evidence for this hypothesis using party-level data from the Comparative Manifesto Project and derived from Tsebelis' veto player approach. We extend their work by testing this hypothesis at the level of individual ministers. Further, because we estimate individual-level preferences, we are able to distinguish between preferences of ministers from the same party.

A crucial factor in the effectiveness of delegating fiscal authority is that the finance minister is supported by the prime minister when making spending decisions. Indeed, a common assumption made in the literature on budgetary politics is that the prime minister and finance minister both weigh the collective interests of the government rather than those of specific spending departments (Von Hagen and Harden, Reference Von Hagen and Harden1995, 774).

We argue that this assumption severely misrepresents intra-cabinet politics and conflict over the redistribution of financial resources. Wildavsky and Caiden (Reference Wildavsky and Caiden2004) describe budgets as struggles for power, where budgetary decisions are essentially decisions about the distribution of power made through a “dance of the dollars.” This provides ample opportunity for potential conflicts of interest between the finance and prime minister. For example, Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou in Greece in the 1980s offered virtually no support to his finance minister on budget matters (Hallerberg, Reference Hallerberg2004, 64). While British Prime Minister Tony Blair provided support to Chancellor Gordon Brown over many economic matters (Hallerberg, Reference Hallerberg2004, 64), they clashed, for example, over health spending (Heffernan, Reference Heffernan2005). Policy conflict within the Blair–Brown duopoly is well documented in the proliferation of cabinet committees (Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy, Dunleavy, Gamble, Heffernan and Peele2006) and establishment of clear “policy fiefdoms” (Hennessy, Reference Hennessy2005). The relationships vary even within the same country over time. While Margaret Thatcher consistently backed Chancellor Howe, her successor, John Major, was more likely to side with spending ministers rather than Chancellor Lamont although he later supported Lamont's replacement, Chancellor Clarke (Hallerberg, Reference Hallerberg2004, 73–78). In Ireland, Taoiseach Ahern provided full support to his finance minister Charlie McCreevy from 1999 to 2002, making him arguably the strongest Minister for Finance in recent Irish history. However, they occasionally clashed over health care spending and waning support by the Taoiseach resulted in McCreevy being dispatched into exile to Brussels as a European Commissioner in 2004 (Leahy, Reference Leahy2009).

What explains the breakdown of effective delegation in some governments? We argue that changes in macroeconomic conditions can significantly alter the prime minister's rational evaluation of the aforementioned trade-off between the benefits and costs of delegation. During economically good times when sufficient funds are available and borrowing is under control, delegation is cheap because there is relatively little competition over the precise allocation of government resources. During economic crisis, in contrast, the cost of delegation may outweigh its benefits. When difficult decisions have to be made sacrificing spending in some areas and ring-fencing spending in others, even small differences in preferences over budgetary allocations can lead to major disagreement between the prime minister and finance minister, ultimately leading to a breakdown of the delegation mechanism. Thus, the macroeconomic environment and its effect on competition between the prime minister and finance minister structures decisions on budgetary redistribution. This argument is a novel extension of Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen (Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009) of the delegation between the prime minister and finance minister, theorizing that this delegation mechanism can be affected by external events. From this discussion we develop our next hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

An increase in competition between the prime minister and finance minister during economic crisis will lead to less delegation of fiscal authority and hence less influence of the finance minister over budgetary outcomes.

To summarize, we believe that decisions over budgetary redistribution across departments structure intra-cabinet political competition. The preferences of individual ministers contrast those of the finance minister and prime ministers. At the same time, the prime minister and finance minister may also have distinct and different preferences over budgetary spending. During times of economic crisis, standard fiscal governance instruments may be augmented with more direct involvement of the prime minister in decisions over budgetary redistribution.

3. Fiscal governance and intra-cabinet politics in Ireland

Connaughton (Reference Connaughton, E and M2012) describes government formation in Ireland, where individual members of parliament (TDs) are appointed to ministerial portfolios subject to constitutional provision, at the absolute discretion of the prime minister (Taoiseach). The selection is made from a relatively small pool of experienced TDs, all with very similar backgrounds (mostly teachers, lawyers, and trade union officials) who are all personally known by the Taoiseach. Qualification for the post is based on geography, personal relationships and loyalty, expertise, popularity, and tenure within the party, gender, as well as idiosyncratic motivations of the Taoiseach (O'Malley, Reference O'Malley2006; O'Malley and Martin, Reference O'Malley, Martin, J and M2010).

The Taoiseach also appoints ministers of state (junior ministers) who are not members of the cabinet but support senior cabinet ministers. Junior ministers have few formal powers, with government ministers retaining statutory functions and political responsibility at all times (O'Malley, Reference O'Malley, E and M2012, 42). Thies (Reference Thies2001) suggests that junior ministers may perform a monitoring function over coalition partners. However, this is unlikely in the Irish case because of the small number of junior ministers and their very narrowly-defined roles in government departments (Martin, Reference Martin, E and M2012, 155–157).

In the overall process of government formation, the Taoiseach's selection of the Minister for Finance is usually the most consequential, with significant attention given to intra-party balance and coalition considerations (Leahy, Reference Leahy2009, Reference Leahy2013). Within the Irish government, the Taoiseach is viewed as first among equals, while since 1966 the Minister for Finance is consistently viewed as second among equals (Considine and Reidy, Reference Considine and Reidy2008). The central role of the finance minister and his or her department in the Irish political process is derived from both process of government decision-making and the constitution.

Charlie McCreevy (Minister for Finance from 1997 to 2004) was fond of pointing out that “he was a constitutional officer like the Taoiseach” (Leahy, Reference Leahy2009, 182), since Minister for Finance is the only minister named in the constitution. Procedurally, any policy contributing to public expenditure (which is almost all policy) can be vetoed by the finance minister. Any policy proposals taken to the cabinet by spending ministers must first go through the Department of Finance before circulation, while the Minister for Finance may bring submissions to Cabinet meetings without prior distribution (Considine and Reidy, Reference Considine, Reidy, E and M2012, 89). During such meetings each decision is recorded by the secretary to the government and if the decision involves money or personnel it is counter-signed and qualified by the Minister for Finance (Quinn, Reference Quinn2005, 3). According to public financial procedures, any legislative proposal that incurs expenditure requires an explicit sanction of the Minister for Finance, and the voting of money by parliament (Dáil Éireann) or inclusion of an allocation in a legislative act does not constitute such sanction (Department of Finance, 2008, Section A4.9).

In its recent economic history, Ireland experienced both standard fiscal governance mechanisms. In the period 1985–1997, it had a contract mechanism in place, however, this was replaced with the delegation mechanism in 1998 (Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen, Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009, 50). The structure of the budgetary process has become more centralized over time and is currently one of the most centralized among the EU15 states (Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen, Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009, 74). The change to the delegation mechanism in Ireland happened at the same time as the appointment of Charlie McCreevy as Minister for Finance in 1997. McCreevy enjoyed unprecedented levels of political independence in the formulation of fiscal and economic policy (Leahy, Reference Leahy2009, 182–183).

The presentation of the annual budget is the main event of the financial and political calendar, the so-called budget ‘big bang’ (Leahy, Reference Leahy2013, 340). Considine and Reidy (Reference Considine, Reidy, E and M2012, 98–100) describe how preparation of a new budget starts early in the year with expenditure estimates. Stakeholders are invited to make submissions during an open consultation process. Bargaining over the expenditure side is discussed in bilateral meetings between finance officials and individual spending ministries. For difficult decisions, the respective ministers become involved in negotiations.

Spending ministers are expected to represent their departments in budgetary negotiations. Connaughton (Reference Connaughton, E and M2012, 67) quotes an official as saying that a newly-appointed minister is told that these negotiations represent “a test of his manhood as far as the department was concerned … [since] if you cannot protect your department budget you are not a good minister.” Irish ministers enjoy a large degree of autonomy in day-to-day policy making within their departments (Farrell, Reference Farrell, M and K1994), with the Department of Finance retaining a veto on all major spending initiatives Considine and Reidy (Reference Considine, Reidy, E and M2012, 101).

As a strong finance minister under the delegation fiscal governance regime, McCreevy effectively resisted demands for extra spending from cabinet colleagues. Given that all cabinet memoranda must pass through the Department of Finance before it reaches the cabinet, department officials would brief McCreevy on specific aspects of the proposals from other ministers and detailed reasoning for opposing them. This often made McCreevy “as well or better briefed on ministers' proposals than they were themselves” (Leahy, Reference Leahy2009, 402).

Direct intervention of the Taoiseach was often required to obtain any increases in spending through McCreevy. Leahy (Reference Leahy2009, 283–287) details an episode of recurrent battles to increase funding for Micheál Martin's Department of Health. McCreevy staunchly refused any calls for additional funding. This came to a head over additional disability funding and Taoiseach Ahern forced him to relent following booing of Ahern's speech at the Special Olympics opening ceremony. However, some ministers had an inside track with McCreevy. Despite resolutely refusing to increase allocations to most ministers, he was happy to increase social welfare spending—incidentally the main area of concern for Taoiseach Ahern (Leahy, Reference Leahy2009, 201–205). Suiter and O'Malley (Reference Suiter and O'Malley2013) show that geographically-targeted spending (educational and sports grants) in Ireland favors constituencies of the responsible spending minister and the Taoiseach, however, the largest beneficiary is that of the Minister for Finance which received the lion's share of such spending.

The Irish financial and economic crisis changed the nature of budgetary negotiations into haggling over government cuts with ministers often exhibiting “fiscal nimbyism—cut government spending certainly, just not in my department” (Leahy, Reference Leahy2013, 263). Under squeezed budgets, haggling often turned to fights between ministers trying to take a stand for their departments. For example, the first budget of the Fine Gael-Labour coalition in 2011 showed Alan Shatter, holding justice and defense portfolios, in shouting matches with finance and public expenditure officials centering on—but not limited to—who should pay €36m toward the security bill for the visits of Queen Elizabeth and President Obama (Leahy, Reference Leahy2013, 295). The sum constituted about 10 percent of the overall spending cuts that Shatter had to come up with over a three-year period. Shatter was viewed as fighting his corner and it was considered to be a fair fight. At the same time, the ministers in two other big-spending departments (health and social protection) were engaged in unsanctioned briefing of the media against government measures. While not a new political technique, it was the first time it was so aggressively used. As one minister put it to Leahy: “It was the first time that the government started to lose ground and do itself harm” (Leahy, Reference Leahy2013, 296). The government was subsequently blamed in the polls for the leaked measures even though they were never actually implemented in the budget (Leahy, Reference Leahy2013, 341). In subsequent budgets the leaks may have been reduced but angry exchanges between ministers over budget cuts continued (Leahy, Reference Leahy2013, 342–344).

4. Data and method

Our analysis is based on cabinet members' contributions to the annual budget debate. As discussed in more detail in the online Appendix, budget speeches are an excellent data source to measure cabinet members' policy preferences. The budget debate usually takes place in the first week of December of each year and begins with a statement by the Minister for Finance that contains a summary of the budget measures, followed by statements from the official financial spokespersons from opposition parties, the prime minister, cabinet members, party leaders, and backbenchers. The data covering the period since 1922 have been presented in Herzog and Mikhaylov (Reference Herzog and Mikhaylov2017) and previously used in Herzog and Benoit (Reference Herzog and Benoit2015) and Lauderdale and Herzog (Reference Lauderdale and Herzog2016). Due to data availability of comparable budgetary information, we limit our analysis to the time period from 1999 to 2013. To extract latent traits from the budget speeches, we use Wordscores (Laver, Benoit and Garry, Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003). Following our earlier discussion of the delegation regime of fiscal governance, we anchor the scaling dimension in our model by the preferences of the prime minister and finance minister. We aim to scale fiscal preferences of individual cabinet ministers on this dimension, and trace how ministers' positions change over the economic cycle. Further information about the data, including descriptive statistics, and our text scaling model is available in the online Appendix.

Figure 1 summarizes our estimates of ministers' positions on the fiscal governance dimension. The top and bottom lines indicate the positions of the prime minister and finance minister, respectively. The dots represent the positions of all other cabinet members. Our first important result is that, despite strict party discipline and collective cabinet responsibility, cabinet members hold policy positions that are clearly different from each other. While the bulk of ministers tend to be clustered around the mean and median position—a typical feature of this sort of text analysis (Benoit and Laver, Reference Benoit and Laver2007; Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2007)—some are clearly closer to either the prime minister or finance minister. Furthermore, we observe that positions are within the rescaled bounds between the PM and FM in all but one case. This empirically highlights consistent distance between the two anchors and spatial placement of ministers between them. The goal of our analysis is to test whether positions on this dimension are systematically related to changes in budget allocation, and we approach it in the next section.Footnote 1

Figure 1. Estimated policy positions for Irish Cabinet members, 1999–2013. Positions are scaled on the dimension bounded by positions of the Taoiseach (+1) and finance minister (−1). The dashed line indicates the position of the median cabinet member.

Preferences expressed through speeches are of course not strategy free or a reflection of a minister's “true” beliefs. Like the analysis of roll-call data, we can only measure similarity between expressed behavior but not its underlying motivation. It is also possible that expressed preferences are endogenous, i.e., influenced by budgetary decisions in the first place. By using the speeches of the prime minister and finance minister as our training documents, we explicitly estimate the similarity of cabinet members' speeches relative to these two documents. This allows us to estimate positions on the dimension of budgetary statements of the prime minister and finance minister that we argue captures the effectiveness of fiscal governance. This is a specific issue dimension that may or may not be related to any other dimension of political competition. Ministers' positions on this dimension should be first and foremost related to that of their department in broader budgetary haggling, but may also include broader political issues.

The literature on pork-barrel politics suggests that pork spending usually comes in the form of public investment rather than current expenditure (e.g., Khemani, Reference Khemani2004; Drazen and Eslava, Reference Drazen and Eslava2010). In turn, during fiscal adjustments, politicians face the choice of whether to cut current or capital expenditure. The budgetary process is generally characterized by incremental adjustments interspersed by sharp changes (Wildavsky and Caiden, Reference Wildavsky and Caiden2004; Kraan, Reference Kraan1996). The level of budget allocation to individual departments is largely locked in and determined by previous commitments and obligations (such as pensions). The politics of budgetary allocation therefore will determine changes in relative shares of individual spending areas rather than overall sizes of each area of the budget. We therefore use as our dependent variables annual changes (i.e., first differences) of capital and current expenditure expressed as percentages of the total budget. Figure 2 shows the values of this variable for each department and over time.

Figure 2. Annual differences in current and capital expenditures as shares of total budget, 1999–2013.

In terms of current spending, the majority of the budget (between 54 and 77 percent) is spent on education, health, and social services. There is a sharp increase in the share on social spending from about 18 percent in 1999 to more than 36 percent in 2013. This is mostly the result of demand-driven factors and especially because of the sharp increase in the unemployment rate from about 5.5 percent to almost 14 percent over the same time period. As discussed above, intra-cabinet positions should predominantly affect capital spending. This is expenditure on, for example, roads, hospitals, and schools. The largest part of capital expenditure (up to 11 percent) is spent on the environment and transport, with both portfolios having seen significant cuts to their spending shares during the financial crisis. We further see that capital spending has also declined in education and health, while it remained fairly constant in the areas of defense, enterprise, and resources. Further information about our dependent variables, including comparison of their variations in our data, is available in the online Appendix.

5. Regression models

To repeat our main arguments, we expect that spending decisions will reflect the preferences of the finance minister (FM) if a delegation mechanism is in place (Hypothesis 2). To test for this conjecture, we estimate the extent to which changes in budgetary spending in each department are correlated with our estimate of intra-cabinet positions. If Hypothesis 2 is correct, we should find a negative correlation between the two variables.Footnote 2 This would indicate that ministers closer to the FM receive larger budget shares.

We furthermore conjecture that an increase in competition between the prime minister (PM) and FM as a result of tighter fiscal requirements will lead to the breakdown of the delegation mechanism and hence to a reduced influence of the FM (Hypothesis 2). If this is correct, we should find a positive correlation between changes in departmental budget shares and estimated intra-cabinet positions, but only during times of fiscal tightening when resources are limited and questions about budgetary allocations become more prevalent. To test this expectation, we control for two alternative measures in the macro-economic environment together with their interactions with our preference measure. First, we control for annual changes in government debt as a percentage of GDP (ΔDebt). Second, we include changes in the annual unemployment rate (ΔUnempl.) into the model which, in contrast to government debt, is more visible to the general public and hence might be a better measure for political pressure on the cabinet. Both variables are calculated as the average values of the previous time period and thus capture lagged changes in debt and unemployment. The two variables are highly correlated with each other and we therefore estimate their effects in separate regression models.Footnote 3

The two economic variables are direct measures of macro-economic conditions. To tap more directly into the potential conflict between the PM and FM over budgetary decisions, we also estimate a model in which we include dummy variables for two of the three Taoisigh, Cowen and Kenny (with Ahern as the control group), together with the interaction effect between these dummy variables and our estimated intra-cabinet positions. Each dummy variable is coded as 1 for all years in which one of the Taoisigh was in office. Because this is identical to including fixed effects for different time periods, we estimate the model with PM dummies separate from the models with economic indicators.

Theoretical models of the delegation mechanism suggest that finance minsters might be biased toward ministers from their own party (Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen, Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009). To test for this hypothesis, we include a dummy variable that indicates whether a cabinet member is from the same party as the FM. Because our data set includes both cabinet and junior ministers, we also include a control variable for junior ministers in order to test for systematic differences between the two groups. Finally, we include dummy variables for each portfolio (with the agricultural portfolio excluded as the control group) to account for differences in the magnitude of changes in spending, such as the increase in unemployment spending during the economic crisis.Footnote 4

6. Results

Table 1 summarizes the results of six regression models. Our estimated measure of intra-cabinet position-taking is included in all six models. In the first two models, we estimate the effects of the two macro-economic variables and their interactions with the estimated positions on capital and current spending. The third model includes the PM dummy variables and their interaction effects.

Table 1. OLS regression of changes in budget shares conditional on changes in debt (% of GDP), changes in the unemployment rate (%), PM in office, and control variables

Note: Standard errors clustered by budget years.

*p < 0.05.

Looking first at the effect of intra-cabinet positions across all models, we find support for Hypothesis 2 in the models controlling for debt and PM, respectively. Across these two models with capital spending as the dependent variable, we find a significant effect of positions on changes in budgetary shares. The coefficient is negative, meaning that cabinet members who express preferences closer to the FM have received a larger share of the budget, while those closer to the PM have their budgets decreased. The size of the coefficient is between −0.18 and −0.21. In substantive terms, this corresponds to a decrease of a portfolio's budget share by, on average, 0.07 percentage points if a minister's position changes by one standard deviation on the policy scale.Footnote 5 In absolute terms, this corresponds to an average decrease of €32.5mln in a department's capital expenditure based on an average total budget of €46.4bln between 1999 and 2013. With an average capital expenditure of €492mln by portfolio, this absolute change corresponds to a change of 6.6 percent in the average portfolio's capital expenditure.

This finding implies that, on average, FMs in our sample were able to allocate parts of the budget according to their preferences. This indirectly provides evidence that delegation of fiscal authority in Ireland was successful because FMs had some leverage over budgetary outcomes. It can also be seen as evidence for Hallerberg, Strauch and von Hagen's (Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009) claim that successful delegation induces a bias because some of those budgetary outcomes may have favored the FM's own constituents. Furthermore, we see that the effect we found only holds for capital but not current spending. As discussed previously, this is in line with the literature on pork-barrel politics and fiscal governance, whereby capital expenditure is more amenable to adjustment than current expenditure due to external economic pressure and political expediency.

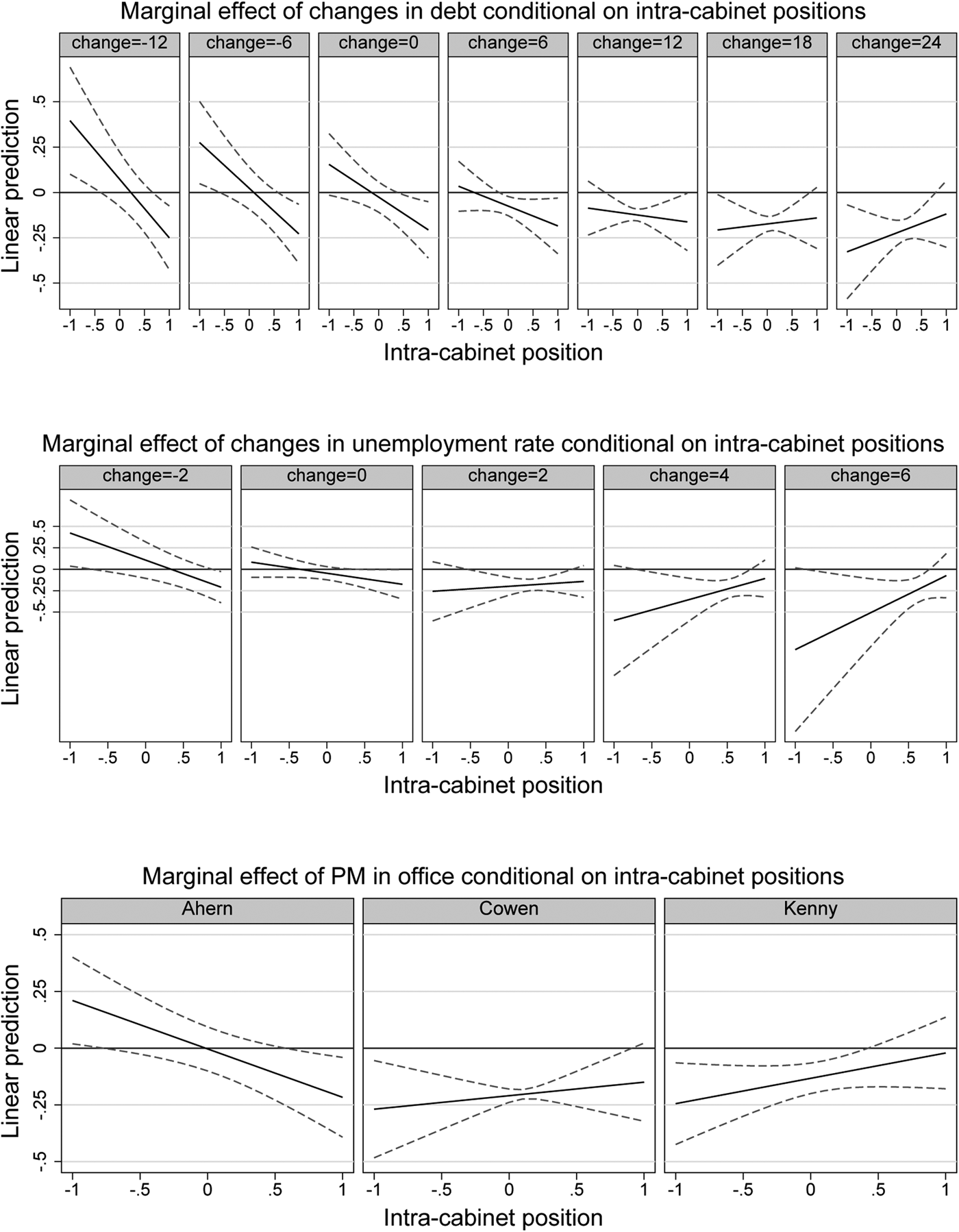

Turning to the effect of macro-economic conditions (ΔDebt and ΔUnempl.) and the test of Hypothesis 2, we find a weak negative effect on capital spending (in the model with ΔUnempl.), but a positive effect when interacted with policy positions. This suggests the effectiveness of delegation decreases with the severity of the financial crisis. To further illustrate this result, we have calculated marginal effects and confidence intervals for changes ΔDebt and ΔUnempl. conditional on intra-cabinet positions. As the first two panels in Figure 3 illustrate, there is a negative correlation between changes in budget shares and positions when macro-economic conditions are favorable. With an increase in ΔDebt and ΔUnempl. (i.e., a worsening of the macro-economic situation), this relationship first flattens and then reverses, which indicates a breakdown of the delegation mechanism because budgetary allocations reflect the PM's preferences rather than preferences of the FM as would be expected under delegation. Our results provide some evidence in support of Hypothesis 2 that delegation is only effective during economic good times and not necessarily sustainable during financial and economic crises.Footnote 6

Figure 3. Predicted values for changes in capital expenditure shares conditional on intra-cabinet policy positions and changes in debt (top panel), changes in unemployment rate (middle panel), and changes in prime minister (PM) in office (bottom panel). Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence bands. All values are calculated from the OLS regression results in Table 1, with all other variables held at their mean values.

As expected, we find similar results when the macro-economic variables are replaced with dummy variables for two of the three Taoisigh. While the main effect of intra-cabinet positions is negative, its interaction with the dummy variable for Cowen (in office from 2008 to 2011) and Kenny (2011 to 2013) is positive. Because almost all of the budget adjustments during this time period were spending cuts, our results indicate that ministers closer to the Taoiseach received smaller cuts to their departmental budgets than those closer to the FM. This result provides further evidence that a breakdown of the delegation mechanism under Cowen and Kenny, with the two Taoisigh being able to guard their preferred ministers and portfolios against the austerity measures of the FM.

As before, we further illustrate this result by calculating the marginal effects for different values of the key variables. The bottom panel in Figure 3 plots the marginal effect of changes in capital expenditure shares conditional on intra-cabinet positions and PM in office. The figure shows that the delegation mechanism worked particularly well under Ahern (with McCreevy as FM). We then see a reversal of the effect when Cowen became PM and Lenihan took over as FM, and a similar effect for Taoiseach Kenny and Finance Minister Noonan.

Our interpretation of the results is that delegation to the FM became ineffective when Ireland entered the economic and financial crisis. Faced with the need to implement some of the harshest austerity measures in the country's history, Cowen imposed his own preferences on the budget, protecting ministers and government portfolios closest to his own preferences rather than fully delegating the budgetary process to his finance minister Brian Lenihan. As Leahy (Reference Leahy2009, 442) points out “Lenihan favoured earlier and deeper cuts; the Taoiseach didn't like the politics of it.” The general observation that Lenihan received relatively little support from Cowen supports this interpretation. Daniel McConnell, a political correspondent for the Irish Independent (the country's largest newspaper), for example, writes:

“Their [Cowen and Lenihan's] political and personal relationship was dysfunctional and went far beyond a mere personality clash. The disintegration of their relationship was personal and it had a serious impact on the workings of government. Mutual suspicion and mistrust between the two Brians proved disastrous for their party Fianna Fail, their Government and the country. Cowen, instead of seeking counsel from his most senior minister, sought solace and advice from his tight-knit coterie of ‘Dail Bar’ cronies, who harboured animosity to the Cambridge-educated finance minister […].”Footnote 7

McConnell's analysis furthermore points to the competition over leadership between the two ministers, which we have argued is a common feature of intra-cabinet conflict, and which was particularly severe in this instance:

“Lenihan quickly became frustrated and disillusioned with his leader, distanced himself from him as a result and ultimately realised that Cowen was not up to the job. It eventually came to the point where Lenihan, despite his terminal illness, was openly plotting against his leader.”Footnote 8

Our results indicate potential fragility of the fiscal authority delegation mechanism in adverse economic environment. This has important implications for the design of budgetary rules. Most recently, Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2013) have shown that appropriate budgetary rules, which includes the centralization of budgetary decision-making through delegation to a powerful finance minster, can mitigate the common-pool resource problem. Our results further add to this finding by showing that effective budgetary rules also require the support of the prime minister. While generally an effective mechanism during economic “good times,” it can quickly break down if the government is forced to implement unpopular austerity measures and its prime minister is not fully committed to delegating power to the finance minister.

Finally, it is worth pointing out one other result in Table 1: whether or not a cabinet minister is from the same party as the FM has no significant impact on budget allocation. In other words, being from the same party as the FM is not sufficient to be favored in the budget-allocation process, it is rather the position of the individual minister with respect to the two main cabinet leaders. This result contributes to the relatively small literature that looks into the politics of budgetary composition (e.g., Bräuninger, Reference Bräuninger2005; Tsebelis and Chang, Reference Tsebelis and Chang2004; Wehner, Reference Wehner2010).

7. Conclusion

This paper provides the first empirical evidence that intra-cabinet politics has an effect on policy outputs in parliamentary democracies. Drawing on work on fiscal governance (Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2013; Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen, Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009) and intra-cabinet decision-making (Laver and Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1994; Dowding, Reference Dowding, Strangio, Hart and Walter2013), we develop two hypotheses. First, under effective delegation of fiscal authority, budgetary outcomes should reflect the preferences of the finance minister. Second, we hypothesize that effective delegation crucially depends on the macro-economic environment. More specifically, we argue that a worsening of the economic situation can introduce competition between the prime minister and finance minster over the allocation of the budget, which can ultimately lead to a break down of the delegation mechanism.

To test our claims, we draw on an original data set of budget speeches from Ireland. As a country that has experienced both rapid economic growth and a recent economic crisis, it provides an ideal test case for our claim that the effectiveness of fiscal delegation depends on the macro-economic context. Furthermore, the fiscal governance mechanism in Ireland is institutionally similar to several West European parliamentary democracies where prime minister and finance minister come from the same party.

Our first finding provides support for one of the main implications from the literature on fiscal governance (Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen, Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009; Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2013). The delegation mechanism performs as expected by providing the finance minister with sufficient discretion over fiscal governance. This is based on an analysis that shows that ministers closer to the finance minister receive a larger proportion of the budget than those with preferences closer to the prime minister. While we are unable to say whether such spending is optimal for the social welfare function, we can conclude that the discretionary powers of finance ministers are exercised as expected under the delegation mechanism. As such, our paper makes an important contribution to the literature on fiscal governance by providing the first micro-level support of effective delegation.

Our second finding is that the discretionary power of the finance minister is not constant over the economic cycle. When cabinets face decisions to cut expenditure across departments, the prime minister can effectively intervene to protect those closest to him. More specifically, we find that delegation breaks down when the economy faces high levels of government debt and unemployment. However, it is exactly under such conditions that delegation of fiscal authority to a strong finance minister has been propagated in previous academic research as a solution to fiscal problems. Put differently, when delegation is needed the most, the prime minister has the least motivation to give fiscal authority away. This is an important result for our understanding of the effectiveness of fiscal delegation during economic crisis and opens avenues for further research to investigate alternative mechanisms that are both effective for fiscal consolidation and aligned with the preferences of the key players.

Our findings have important implications for the literature on delegation and fiscal governance. Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen (Reference Hallerberg, Strauch and Von Hagen2009) have shown that delegating budget decisions to a strong finance minister can mitigate the common pool problem of fiscal spending. However, their focus has primarily been on delegation mechanisms between coalition parties, such as the ideological distance between coalition partners, existence of a fiscal contract, or institutional powers given to the finance minister. Focusing on the effectiveness of delegation between prime ministers and finance ministers from the same party, we have shown that delegation can break down as a result of external effects—which ultimately means that fiscal delegation can be ineffective given the powers of the prime minister to intervene in the decisions of the finance minister. After all, it is the prime minister who ultimately holds control over the cabinet and has the power to select and de-select ministers (Dowding and Dumont, Reference Dowding and Dumont2008).

Finally, our results make a significant contribution to the growing literature on quantitative text analysis. While the technique we use is based on a well-known implementation of supervised machine-learning, we show that when applied to legislative speeches, it is possible to measure positions that are correlated with significant and important public policy outcomes. Legislative speeches are therefore not just cheap talk, but contain relevant information about legislators' preferences over key decisions.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.40