The common assumption is once again the notion (not so much articulated as put into practice) that the constitution in principle gives the interpreter a free choice of the different theories; no theory is ruled out, and the interpretation of the fundamental rights can be based on any of them, whether generally or on a case-by-case basis. It is precisely this assumption that needs to be challenged critically.

Preface

The language of justification pervades the adjudication of constitutional rights. Rights-claimants must justify their claims about the protections that rights afford, while governments must justify their claims about the restrictions to which rights may be subject. These practices raise a fundamental question: What justifies judgments about constitutional rights? In recent decades, attempts to answer this question have become hopelessly deadlocked.

Among constitutional scholars, the standard view is that constitutional justification raises no distinctive moral principles. Instead, constitutional justification is an exercise in ordinary moral justification. Of course, proponents of the standard view often disagree about what is morally desirable, but they share the broader idea that what morality demands is fully comprehensible and specifiable apart from constitutional law. Constitutional justification, then, is simply moral justification on a larger stage.

My aims in this Element are both critical and constructive. As a critical matter, I will demonstrate that the standard view generates an impasse between two competing theories of constitutional rights. The first engages in legally unconstrained moral reflection to identify the protections that fall within the scope of a right. The second engages in legally unconstrained moral reflection to determine the strength that a right possesses with respect to opposing considerations. While these theories polarize constitutional thought, I will show there is no basis for preferring either one. Each begins by affirming the standard view, and each concludes by (1) abandoning the rule of law, (2) rendering constitutional rights incapable of regulating the exercise of public power, and (3) disregarding constitutional text. In the impasse that ensues, each theory “is able to make the other look quite bad” but unable to defend itself.Footnote 1

As a constructive matter, I will formulate an alternative to the standard view of constitutional justification. I will argue that, far from being an exercise in ordinary moral reasoning, rights-based constitutional order is a distinctive moral project with its own corresponding justificatory method. This method escapes the impasse to which the standard view inevitably succumbs.

The moral project of rights-based constitutionalism consists in rendering all public authority accountable to the inherent rights of each legal subject.Footnote 2 Rights-based constitutional order is not synonymous with constitutional rights. Earlier forms of governance recognized that persons are bearers of rights (rather than merely subject to duties); that these rights are inherent (rather than acquired and revocable); that these rights are universal (rather than the preserve of a privileged few); that the basic function of government is to respect and protect these rights (rather than to pursue the private ends of those who happened to hold public power); and that these rights must possess the force of supreme law (rather than ordinary law). However, these innovations failed to confront a basic difficulty. Because legal subjects had no way of vindicating their rights, public authorities remained capable of violating rights with impunity, whether though neglect, inadvertence, or persecution. In short, the presence of constitutional rights did not establish the absence of plenary power.

Rights-based constitutional order confronts this difficulty by introducing a further innovation, the constitutional complaint.Footnote 3 This practice enables any individual to come before a politically independent judicial body to challenge the validity of any act or omission of any public authority as a violation of a constitutionally guaranteed right. By transforming rights from “a mere guideline of a political, moral, or philosophical nature” into justiciable constitutional norms,Footnote 4 rights-based constitutional order reorients the relationship between ruler and ruled. Within rights-based constitutional order, no public authority possesses plenary power and no legal subject stands at the mercy of their government. Instead, rights-based accountability constrains every public authority and safeguards every legal subject.

The emergence of the constitutional complaint raises a new question: What makes the resolution of a constitutional complaint justified? From the standpoint of the standard view, one answers this question by taking the existence of constitutional complaints for granted and then asking, all things considered, how they should be resolved. From this standpoint, there are as many theories of constitutional justification as there are schools of moral philosophy, and any attempt to establish the primacy of a particular theory is fraught with difficulty. However, from the standpoint of the moral project of rights-based constitutional order, the justificatory landscape could not be more different. The practice of constitutional adjudication (and the vast scholarly literature that it has spawned) offers opposing methods of resurrecting plenary power, but only one method that actualizes the accountability of all public power to rights. I call this method the system of rights. My aim in this Element is to articulate its structure and significance.

I proceed as follows. Section 1 explores the impasse of constitutional thought by expounding the standard view, the opposing theories that it generates, and the vulnerabilities that these theories share. Section 2 contrasts this justificatory structure with that of the system of rights. From the standpoint of the standard view, a constitutional judgment is justified only if it corresponds to moral demands that are conceivable and specifiable apart from rights-based constitutional order. In contrast, from the standpoint of the system of rights, a constitutional judgment is justified only if it is supported by a form of reasoning that maintains the accountability of all public power to rights. Unlike the standard view, this form of reasoning can neither be comprehended nor specified apart from rights-based constitutional order.

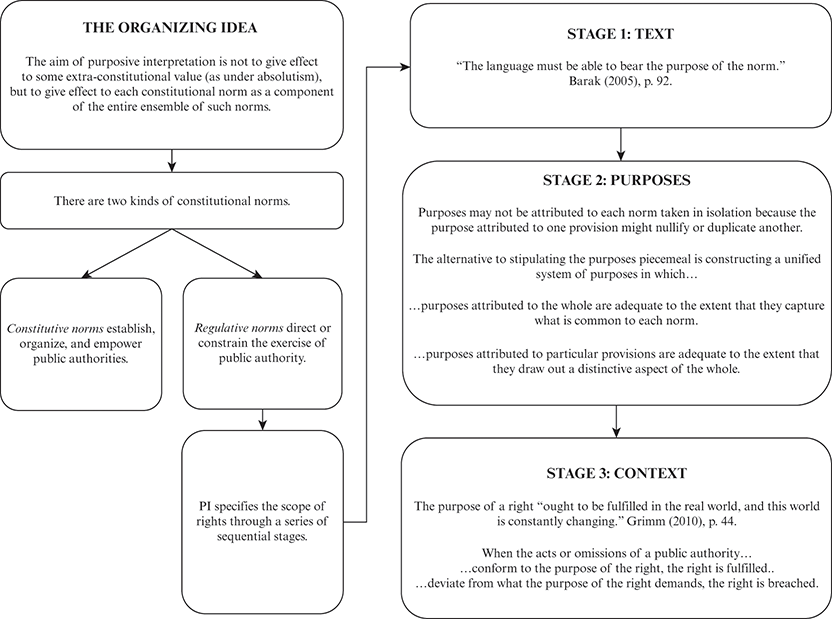

Sections 3 and 4 elaborate this form of reasoning by exploring two doctrines integral to rights-based constitutional ordering, purposive interpretation and proportionality. Proponents of the standard view typically insist that these doctrines are either dangerous distractions that draw attention away from the freestanding moral considerations that really matter or benign invitations to engage in legally unconstrained moral reflection. In contrast, the system of rights shows that these doctrines play an indispensable role within the distinctive moral project of rights-based constitutional order. From the standpoint of this moral project, what is most striking about these doctrines is that if one abandons even a single component – or if one alters the sequence in which these components appear – the constitutional complaint would fail to render public authority accountable to rights, and legal subjects would find themselves, once again, at the mercy of a plenary power. Accordingly, the structure and substance of these doctrines can be elucidated on constitutional law’s own terms. Section 3 justifies purposive interpretation and explains how it regulates judgments concerning the scope of rights, while Section 4 justifies proportionality and explains how it regulates judgments concerning the strength of rights.

Section 5 concludes that the system of rights possesses decisive advantages over the standard view of constitutional justification. The standard view creates an impasse between competing theories that are jointly incapable of taking the rule of law, the regulative character of constitutional rights, or constitutional text seriously. The system of rights, in contrast, avoids each of these difficulties and expounds the normative connection between rights-based constitutional order and its most fundamental doctrines.

1 The Impasse

In his classic essay “Taking Rights Seriously,” Ronald Dworkin surveyed the constitutional landscape and observed “two very different models” of constitutional rights.Footnote 5 The first defines rights broadly and then balances them against “the demands of society at large.”Footnote 6 The second regards balancing with suspicion and seeks to carefully delineate the “definition of a particular right.”Footnote 7

In the last fifty years, these models have become increasingly systematic and antagonistic. With respect to their systematicity, each model elaborates the structure of constitutional rights and a corresponding method of interpretation and adjudication. With respect to their hostility, each model seeks to establish its superiority by demonstrating that the other defies the rule of law, renders constitutional rights nugatory, and disregards constitutional text.

This section (1) explains why constitutional thought has splintered into these opposing models; (2) formulates a succinct and systematic statement of the structure of each model; (3) shows that each model is vulnerable to the same objections; and (4) traces the vulnerabilities of these models back to their source: the shared idea that constitutional justification is simply ordinary moral justification.

1.1 Bentham’s Challenge

More than two centuries ago, when the idea that “[t]he aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man”Footnote 8 began to transform the practice of constitutional law, the philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham issued a fundamental challenge to all declarations of rights, both “actual and possible.”Footnote 9 His aim was to show, once and for all, that subjection to plenary power is an ineliminable feature of any legal order. Although the rights formulated in the declarations of his time (and the constitutions of our own) purport to establish a form of legal ordering in which each legal subject is protected from their government, Bentham argued that rights either leave public power unconstrained or supplant it with anarchy.

The structure of Bentham’s challenge is simple. Once rights are declared, they must stand in some relationship to legislative authority. Bentham postulated two possible relationships: legislation might exceed the strength of rights or rights might exceed the strength of legislation. Bentham termed the former possibility legal rights, the latter natural rights.

Legal rights, he explained, coexist with legislative authority but cannot constrain it. If legislation reigns supreme over rights, then a legislative authority may specify the scope of rights by placing their boundaries in whatever location it deems fit. But when the boundaries of rights are established by legislative authority, persons necessarily remain at its mercy: “Suppose a [declaration] to say – no man’s liberty shall be abridged, but in such points as it shall be abridged in, by the law. This, we see, is saying nothing: it leaves the law just as free and unfettered as it found it.”Footnote 10 Rights that are products of legislation afford no protection from legislation.

Whereas legal rights are powerless to constrain legislation, legislation is powerless to constrain natural rights. Because the strength of natural rights exceeds that of legislation, there is no right to which “any government can, upon any occasion whatever, abrogate the smallest particle.”Footnote 11 Natural rights are thus “imprescriptible” (or as we might say, conclusive, peremptory, or inviolable).Footnote 12 And because natural rights are formulated in “words and propositions of the most unbounded signification”Footnote 13 – for instance, protecting the “[u]nbounded liberty” to do or not do “on every occasion whatever each man pleases”Footnote 14 – the scope of natural rights encompasses all conceivable forms of human conduct. Bentham famously denounced this combination of ideas as “nonsense upon stilts”Footnote 15 because if rights have both the strength of supreme law and a scope that extends boundlessly, legislation cannot so much as “stir a step.”Footnote 16 For Bentham, the very notion that rights reign supreme over legislation imperils legislative authority: “[F]rom this declaration of rights, learn what all other declarations of rights – of rights asserted as against government in general, must ever be, – the rights of anarchy – the order of chaos.”Footnote 17 In their eagerness to ensure that persons were not placed at the mercy of legislative authority, defenders of natural rights repudiated the very possibility of legislative authority regulating human conduct.

Bentham’s challenge asks how rights can be reconciled with legislative authority. If the strength of legislation exceeds that of a right, as in the case of legal rights, then the scope of each right lies wherever legislation happens to place it and persons find themselves “at the mercy and good pleasure of the law.”Footnote 18 Alternately, if the strength of rights exceeds that of legislation, as in the case of natural rights, then rights preclude the very possibility of legislative authority regulating human conduct. Rights, then, are either subordinate to legislative authority or preclusive of its exercise. Between these “two rocks,” Bentham maintained, defenders of rights seek a middle ground that does not exist.Footnote 19 Whether one affirms legal or natural rights, the simple claim that rights both coexist with legislative authority and yet constrain its exercise has no basis.

Bentham’s critique of natural rights is propelled by two ideas: a fundamental insight that every theory of supreme law rights accepts, and a fundamental misconception that every contemporary theory of constitutional rights rejects. The insight is that a theory of constitutional rights must offer an account of both the scope and strength of rights. The scope of a right consists in the protections that it secures. The strength of a right consists in its power to withstand opposing considerations. Bentham’s misconception is that any theory of constitutional rights must claim both that rights are boundless in their scope (insofar as they encompass all human conduct) and unyielding in their strength (insofar as any legislation that violates a constitutional right is invalid). Bentham’s achievement in his famous essay was to show that these claims cannot travel together. What he failed to establish is that these claims exhaust the possible understandings of constitutional rights.

1.2 Two Models of Rights

In the centuries that followed Bentham’s intervention, proponents of constitutional rights fragmented into two opposing camps. Each accommodates his insight that if constitutional rights are to regulate (rather than preclude) legislative authority, they cannot be both boundless in their scope and absolute in their strength. And each camp retains Bentham’s understanding of either the scope or the strength of constitutional rights, while mitigating the rigor of the other component. What I will call the absolutist model conceives of rights as unlimited in strength but limited in scope.Footnote 20 What I will call the relativist model reverses these commitments by conceiving of rights as limited in strength but unlimited in scope.Footnote 21 Each approach mirrors the other’s structure: relative rights are broad but subject to restriction; absolute rights are specific but immune from incursion. The structures of Benthamite legal rights, Benthamite natural rights, absolute rights, and relative rights are contrasted in Table 1.

Table 1 Models of rights

| Benthamite Legal Rights | Benthamite Natural Rights | Absolute Rights | Relative Rights | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | Limited | Unlimited | Limited | Unlimited |

| Strength | Limited | Unlimited | Unlimited | Limited |

The scope of relative rights encompasses “every form of human activity.”Footnote 22 They include not only the “classical catalogue” of “freedom of speech, association, religion and privacy, narrowly conceived,”Footnote 23 but also “relatively trivial interests.”Footnote 24 Rights relativism animates the German Federal Constitutional Court’s interpretation of Article 2(1) of the Basic Law – the right to the free development of one’s personality – as a “right to do as one pleases.”Footnote 25 By conceiving of this right as guaranteeing “freedom of action in a comprehensive sense,” the Court has held that persons have a prima facie right to do a variety of “mundane things,” including “a right to ride horses through public woods, feed pigeons in public squares, smoke marihuana and bring a particular breed of dogs into the country.”Footnote 26 Proponents of the relativist model are eager to extend the frontiers of constitutional rights still further. Relativist rights protect not only conduct that is moral and amoral, but also conduct that is immoral.Footnote 27 If there is a prima facie right to do as one pleases, then there must be a prima facie right to do wrong, whether by engaging in defamation, theft, or even murder.Footnote 28

When the relativist model turns from the scope of rights to their strength, it holds that rights are simply prima facie claims that enjoy “no priority over countervailing considerations of policy.”Footnote 29 These claims about the scope and strength of rights are connected. Because the scope of a relative right is not confined to matters of “special importance,” a relative right possesses no “special normative force.”Footnote 30 Within this model, the central question that constitutional rights raise is not whether a person has a prima facie right to engage in a particular activity. Since Bentham’s day, proponents of the relativist model have insisted that persons have a “right to everything indiscriminately.”Footnote 31 Instead, the central question concerns the strength of rights, more specifically, whether public authorities are justified in restricting a prima facie right in a given context.Footnote 32 The relativist answer is that, where the moral reasons that support constitutional protection are outweighed by the reasons that oppose it, a prima facie right is susceptible to restriction. Alternately, where the moral reasons that support constitutional protection outweigh those that oppose it, the restriction of a prima facie right is morally unjustified.Footnote 33

Proponents of the relativist model claim that its virtues extend in two directions. On the one hand, the model purports to capture the appropriate relationship between legislation and morality. Legislative authority is constrained whenever the moral reasons that support constitutional protection outweigh the reasons that oppose it. Conversely, legislative authority is unconstrained whenever the moral reasons that oppose constitutional protection outweigh those that support it. On the other hand, the model claims to illuminate contemporary constitutional practice by offering an integrated explanation of why courts around the world recognize that rights possess a broad scope but a limited strength, as indicated by the presence of limitation clauses and the proliferation of the doctrine of proportionality, which culminates in the balancing of rights against opposing considerations.

In the eyes of its absolutist critics, rights relativism represents a “devaluation of [the] moral currency” of rights.Footnote 34 Having placed all human conduct within the scope of constitutional rights, the relativist account places “genuine and genuinely inviolable rights, such as the right of an innocent person not to be intentionally or negligently killed … on the same level as spurious (because inflated) claims of rights,” such as the right to kill the innocent.Footnote 35 Because the relativist camp insists that constitutional rights protect all human conduct, relativism ultimately dilutes the strength of genuine rights in order to ensure that spurious ones remain susceptible to restriction. In the resulting analysis, both the priority and the purpose of constitutional rights is lost. The priority of constitutional rights is lost because even though relative rights have the status of supreme law, they may be balanced against any consideration that opposes them. The purpose of constitutional rights is lost because relative rights may, in principle, be balanced away. Thus, absolutists complain that the relativist model converts constitutional prohibitions into permissions, with the result that whatever “the Constitution says cannot be done can be done.”Footnote 36 Wherever the relativist model prevails, “everything, even those aspects of our life most closely associated with our status as free and equal is, in principle, up for grabs.”Footnote 37

Absolutists insist that if we are to retain the simple idea that constitutional rights distinguish permissible from prohibited conduct, then the ideas that animate relativism must be inverted. Constitutional rights must be regarded not as prima facie claims that are forfeited whenever the opposing moral reasons are sufficiently weighty, but as inviolable moral conclusions. This claim about the strength of rights has ramifications for their scope. If a constitutional right prevails over any opposing consideration, the protections that a right affords must be confined to specific claims of overriding moral importance.Footnote 38 Whereas conflict is the “natural state” of relative rights,Footnote 39 it is an impossibility for absolute rights. When the scope of each right is carefully specified, rights cannot conflict with one another.Footnote 40 Nor do conflicts obtain between rights and considerations that are not themselves rights. Absolute rights have priority over such considerations and therefore cannot be opposed by them. So conceived, absolute rights are “specific high-priority requirements, and thus though their force is great, their scope is narrow.”Footnote 41

The central question surrounding the absolutist theory of rights is how one justifies what falls within (and what falls beyond) the adamantine boundary of a right. Absolutism has acquired a reputation for refusing to “disclose whatever reasoning in fact underlies the denial of protection.”Footnote 42 But sophisticated versions of absolutism delineate the scope of rights in this way:

[I]t is evident that the assertion, “A has a right to say X to B”, has hundreds if not thousands of possible legal meanings. Correspondingly, it has hundreds if not thousands of possible moral meanings within the moral discourse about what the morally just legal system should stipulate concerning acts of communicating X. No one of all these possible meanings is self-evidently the right moral claim. So the only way to specify the meaning of “right” in some claim of right – and then the only way to justify the restriction of the claim to this specified sense of “right” – will be to appeal to some principles which are pertinent in moral discourse but which are not expressed in terms of “rights.”Footnote 43

On this view, broadly formulated rights present a multiplicity of possible meanings. Since the scope of a genuine right must be specified, and since the sweeping language in which rights are often formulated does not privilege a single specification, one must determine the scope of a right by reference to “values and principles which need not be expressed in terms of rights.”Footnote 44 In other words, the scope of a right is to be ascertained by looking to some conception of morality, justice, or practical reason to which the scope of rights must answer and which, on pain of regress, can be fully explicated without reference to constitutional rights. For example, in the case of the right to free expression, one specifies the scope of the right by looking to morality to distinguish between those expressive acts that may be permissibly constrained – for example, perjury, defamation, false advertising, threats of violence, and obscenity – and those that must be permitted without exception – for example, “speech that is explicitly political.”Footnote 45 When the scope of an absolute right is appropriately specified, the right “brooks no restriction.”Footnote 46

The absolutist model claims to offer a method that takes both rights and morality seriously. The model takes rights seriously by insisting that they possess decisive strength against legislation. Because absolute rights are not susceptible to balancing, they cannot be balanced away. The model takes morality seriously by empowering it to delineate the scope of rights. When the scope of an absolute right is appropriately specified, rights echo whatever morality demands.

When absolutists attack relativists for indiscriminately placing both genuine and spurious rights in the balance, relativists respond that absolutism does not know itself. On the absolutist view, a genuine right is “designated only after the final interaction of all of the reasons bearing upon the justifiability of a given action.”Footnote 47 Once this designation occurs, balancing is precluded because genuine rights are absolute in their strength. However, the absolutist opposition to balancing is more rhetorical than real. Wherever the reasons bearing upon the justifiability of a given action divide into supporting and opposing reasons, absolutism offers no alternative to assessing the weight of the competing reasons. That is what balancing is. Even if absolute rights may not be placed in the balance, the scope of each right is nevertheless “the outcome of an underlying balancing approach.”Footnote 48 And since the “whole point” of absolutism is to determine the scope of genuine rights without engaging in balancing, the theory relies on the very method it repudiates.Footnote 49

Accordingly, the dispute between rights relativism and absolutism is ultimately about when to apply the label right. Whereas relativists apply this label to the inputs of balancing, absolutists apply it to the outputs of balancing.Footnote 50 Once the controversy is framed in this way, relativists maintain that the best approach is the one that balances the reasons that support and oppose constitutional protection in a given context in the most transparent and structured manner. Because absolutists purport to define the scope of rights without engaging in balancing, their inevitable engagements in balancing necessarily lack these qualities.Footnote 51

The leading models of constitutional rights diverge in structure but are similarly morally and institutionally indeterminate.

The absolutist and relativist models can be coupled with any external moral goal: liberal or communitarian, egalitarian or elitist, deontological or consequentialist, secular or sacred. The difference between these models is not the kinds of external moral goals that rights serve, but whether rights serve these goals with their scope or their strength. Debates between relativists and absolutists remain contentious, but nothing of any moral significance is at stake. When it comes to the question of how public authorities should respond to the various constitutional controversies of the day – whether issues of voting rights and electoral regulation, marriage equality, medical assistance in dying, the rights of prisoners and refugees, access to contraception and abortion, or environmental protection – relativists and absolutists speak in one voice in claiming that the exercise of public authority must conform to some external moral goal. Since each model facilitates the fulfillment of any such goal, their enduring dispute is devoid of any practical significance.

Matters of academic genealogy sometimes obscure the fact that relativism and absolutism can serve the same moral goals. To be sure, leading figures in the relativist camp have been liberals, while prominent absolutists have included social conservatives, scrupulously specifying the scope of constitutional rights to preserve religiously inspired understandings of intimacy, reproduction, and family life.Footnote 52 However, the contingency of this alignment is evident from the fact that the same moral goals are equally at home in either model. For example, Robert Alexy and Jürgen Habermas conceive of morality in terms of discourse ethics. However, when it comes to constitutional rights, Alexy leads the relativist paradigm, while Habermas affirms its absolutist counterpart.Footnote 53 Whether discourse ethics determines the scope of exceptionless rights or the strength of defeasible ones, discourse ethics inexorably prevails. Because each of the leading models of constitutional rights may be coupled with any external moral goal, opposing models may serve the same external goal.Footnote 54

So too, the same model of rights can house antithetical goals. For example, Ronald Dworkin’s liberalism stands in diametric opposition to John Finnis’s traditional Catholic worldview. And yet, when it comes to formulating a conception of constitutional rights, each defends the absolutist conviction that when the scope of a right is appropriately delineated, it binds without exception.Footnote 55

Just as the leading models of constitutional rights can accommodate any independent moral goal, so too they can accommodate any institutional arrangement. The relativist camp is compatible with judicial abdication to legislative determinations about the strength that rights possess, judicial imperialism that frustrates legislative authority at every turn, and everything in between.Footnote 56 The absolutist camp exhibits the same institutional flexibility. Absolutism can be coupled with the idea that the judicial role is to ensure that the exercise of legislative authority conforms to the conclusive constraints that rights impose,Footnote 57 or the claim that in a democracy, the appropriate role of the legislature is to delineate the specific boundaries of exceptionless rights.Footnote 58 Relativism is as indeterminate about who should have the final say about the strength of rights as absolutism is about who should have the final say about their scope. The dispute between these models lies elsewhere.

The fundamental dispute in constitutional rights theory, then, concerns whether morality at large determines the scope or strength of rights. Having explicated each of the leading models of constitutional rights, I will now argue that whichever side one takes in this dispute, the rule of law retreats, plenary power prevails, and fidelity to constitutional text is abandoned. I take up each of these issues in turn.

1.3 The Rule of Law Retreats

Whether external moral goals regulate the scope or strength of rights, the rule of law and its values of publicity, prospectivity, and consistency are lost.

As we have seen, the relativist model affirms the following ideas: all conduct falls within the scope of some constitutional right; all legislative acts or omissions that impact conduct infringe a constitutional right; acts or omissions that infringe a constitutional right must be justified; justification consists in balancing the reasons that support and oppose constitutional protection in a given context; and, finally, one ascertains the strength of these reasons by engaging in “general practical reasoning” that “lacks the constraining features that otherwise characterise legal reasoning.”Footnote 59 From the relativist standpoint, the correctness of a judgment concerning the strength of a constitutional right “depends upon value-judgments, which are themselves not controllable by the balancing procedure.”Footnote 60

The relativist claim that the strength of a constitutional right is determined by legally unconstrained moral reflection undermines the rule of law. As the absolutist theorist Francisco J. Urbina explains:

The values associated with [the rule of law] – such as certainty and predictability in human relations – are severely harmed, if not sacrificed, when we make law through legal categories that are so vague that they allow judges to reason morally on what is the best solution to the case, without any effective constraint imposed by the law. The law then becomes uncertain and unpredictable, and there is no guarantee that state power will be bound by clear and previously established legal rules, known by its subject, and applied equally to those in the same situation.Footnote 61

Under rights relativism, what a charter of rights ultimately protects is not a publicly established set of rules and principles articulating a particular understanding of the relationship between free persons and their government. Instead, a charter of rights protects the legally unfettered discretion to use the strength of rights as an instrument for advancing some external moral goal. The constitution is thereby reduced “to a formal shell, which … admits very different and even heterogenous ideas of order successively and simultaneously, without being upheld by one.”Footnote 62 There is nothing of the rule of law in this.

However, when absolutists excoriate their relativist counterparts for abandoning the rule of law, they issue an objection that is equally destructive of their own position. As we have seen, the difference between relativism and absolutism is not whether legally unconstrained moral reasoning determines what constitutional rights demand, but how it does so. Under the relativist regime, one determines the strength of rights by appealing to “first-order political morality.”Footnote 63 The result is that determinations about the strength of rights (and so too the constitutionality of legislation) are legally unconstrained. If one substitutes the word strength for scope, the same is true of absolutism. As we have seen, absolutists delineate the scope of rights by engaging in “unencumbered first-order normative argument.”Footnote 64 The result is that determinations concerning the scope of rights (and so too the constitutionality of legislation) lack legal restraint. Whether one sides with absolutism or relativism, legally unconstrained moral reflection determines what a constitutional right demands. Consequently, constitutional law finds itself incapable of controlling “the flood of variations in the interpretation of the fundamental rights.”Footnote 65 What a constitutional right requires may shift from judge to judge and from case to case. Accordingly, with respect to any constitutional controversy, legal subjects cannot ascertain what protections their rights afford, and officials cannot determine what duties they owe.

Debates between relativists and absolutists are often staged as though relativists affirm established constitutional practices while absolutists formulate a critical alternative. But neither model can make sense of the two-stage models that structures constitutional adjudication in courts around the world. In the first stage, the rights-claimant bears the burden of establishing the infringement of a constitutional right. In the second, the state bears the burden of justifying any infringement. Relativists and absolutists reject this two-staged model for a common reason: constitutional justification is a matter of legally unconstrained moral reflection, and such reflection occurs in a single stage. Accordingly, relativists and absolutists agree that one of the two stages is superfluous. The question is which one.

Absolutists retain the first stage and jettison the second:

[O]nly one step is necessary. Courts ask whether a given measure infringes a human right. If so, that measure is in violation of human rights … In order to establish whether a measure infringes a human right, the court will operate with an understanding of what that human right really requires.Footnote 66

From the absolutist standpoint, the content of a constitutional or human right “will turn on one’s understanding of what justice requires.”Footnote 67 When the scope of a right delineates an exceptionless claim of justice, any limitation contemplated by the second stage must be unjustified insofar as it would permit the very acts and omissions that justice prohibits in the first.

Whereas absolutists embrace the first stage and discard the second, relativists embrace the second and discard the first.Footnote 68 From the relativist standpoint, there is no point in delineating “the precise doctrinal boundaries between neighbouring rights, for example, the boundaries between the right to property and freedom of profession, or between freedom of expression and religion.”Footnote 69 Legislation invariably infringes at least one constitutional right – the liberty to do as one pleases. Thus, the relativist camp locates the fundamental moral question at the second stage, where the moral force of the reasons supporting and opposing protection is considered:

The focus of constitutional rights adjudication is on the second stage of rights analysis; and hence judges will be inclined not to develop any doctrines … regarding the first stage if they can resolve the case in a coherent and principled way at the second stage, namely by examining whether there are sufficiently strong reasons for the limitation of the interest at stake.Footnote 70

From the relativist standpoint, constitutional adjudication concerns the strength of rights as determined by “moral argument about the acceptable balance of reasons.”Footnote 71 Since the consideration of these reasons occurs in the second stage, the first is eliminable.

The rule of law cannot survive the two leading theories of constitutional rights. Absolutists engage in legally unconstrained moral reflection to determine the scope of rights, while relativists engage in legally unconstrained moral reflection to determine their strength. In the case of either theory, judgments concerning the constitutionality of legislation are not constrained by law. For rights-based constitutionalism to coexist with the rule of law, we must reject the idea that legally unconstrained moral reflection determines either the scope or the strength of rights. All-things-considered moral reasoning must find its home in the world of peer review, not judicial review. I summarize the argument in this section in Table 2.

Table 2 The rule of law

| The Role of Morality | The Retreat of the Rule of Law | |

|---|---|---|

| The Absolutist Model | Legally unconstrained moral reflection determines the scope of constitutional rights. | The idea that legally unconstrained moral reflection determines what a constitutional right requires is incompatible with the rule of law’s commitment to publicity, prospectivity, and consistency. |

| The Relativist Model | Legally unconstrained moral reflection determines the strength of constitutional rights. |

1.4 Plenary Power Returns

In the decades following the moral horrors of the Second World War, peoples around the world reflected on their own particular experiences of “tyranny and oppression by a political power unchecked by machinery both accessible to the victims of governmental abuse, and capable of restraining such abuse.”Footnote 72 In the spirit of never again, jurisdictions adopted “a new kind of constitutional norms, institutions, and processes … to protect the basic rights of individuals and groups, including the poor, racial and religious minorities, the young and the old, women and more generally, those traditionally deprived of fair and equal access to the law.”Footnote 73 By (1) recognizing that each legal subject is a bearer of inherent rights, (2) elevating inherent rights to the rank of supreme law, (3) establishing that inherent rights bind all public authorities, and (4) rendering inherent rights justiciable before legally expert and politically independent judicial institutions, rights-based constitutionalism seeks to create a legal order in which no person is simply at the mercy of their government.Footnote 74 Rights-based constitutional order is the alternative to forms of governance that subject persons to plenary power.

As we saw in §1.2, not all participants in the debate between absolutists and relativists affirm judicial review. But even among those who do, plenary power is merely relocated from a legislative to an adjudicative body. When absolutism directs the operation of judicial review, judges find themselves legally unconstrained when delineating the scope of rights. Conversely, when relativism directs the operation of judicial review, judges find themselves legally unconstrained when calibrating the strength of rights. In either case, the unconstrained moral reflection of adjudicators is substituted for the unconstrained moral reflection of legislators. While the institutional and argumentative mechanics of plenary power are rearranged, the subjection of legal subjects to plenary power remains intact.

In debates about the structure of constitutional rights, absolutists purport to occupy the “philosophical high ground” by maintaining that rights impose unshakeable moral obligations on public authorities. Every absolute right prevails on every occasion.Footnote 75 So long as one’s attention remains focussed on considerations of strength, absolute rights appear to protect their bearers. However, this protection proves illusory when one’s attention shifts from the strength of absolute rights to their scope. As absolutists explain, the scope of constitutional rights are “conclusions of practical reasoning about what ought to be done,”Footnote 76 “simply the entailments of the virtue of justice,”Footnote 77 and so on. The difficulty for absolutism, then, is that the claim that rights are indefeasible in strength is meaningless if judges are legally unconstrained when determining the protections that fall within their scope. Whenever the scope of an absolute right is specified, rights-bearers find themselves at the mercy of a plenary power.

Relativism takes the opposite path towards plenary power. Because prima facie rights encompass all human conduct, relativists claim to offer a comprehensive system of rights-protection. All legislative acts and omissions that impact conduct infringe one or more prima facie rights, and thus demand justification. While prima facie rights enjoy no priority over opposing claims, relativists insist that such rights are nevertheless “formidable weapons” that prevail whenever the moral reasons that support constitutional protection outweigh those that oppose it.Footnote 78 Relativists are correct to observe that prima facie rights might prevail. But, because relativism maintains that persons have a prima facie right to engage in any conduct whatsoever, the crucial issue is the basis on which judges are to determine the strength that such rights possess in various contexts. Relativism calibrates the strength of rights by directing judges to consider “the correct substantive theory of justice,”Footnote 79 “theoretically informed practical reasoning,”Footnote 80 and “all the relevant moral considerations.”Footnote 81 Accordingly, legally unconstrained moral judgment determines whether a prima facie right prevails or must yield to some opposing consideration. Because judges enjoy legally unfettered discretion when they calibrate the strength of rights, judges possess unlimited power over the fate of rights-bearers.

It is no answer for relativists and absolutists to claim that the inability of constitutional rights to constrain moral reflection allows for the most perfect justice. As absolutist critics of relativism have perceptively observed, the reason why legally unconstrained moral reasoning “can achieve the most perfect justice” is that it also “allow[s] for the most perfect injustice.”Footnote 82 However, absolutists remain serenely unaware of the ramifications of their own objection. If relativism is defective because it is incapable of imposing legal constraints on the moral reflection of judges, then absolutism is defective on the same ground. Within each model, the absence of legal constraint and the absence of legal protection are two sides of the same coin.

The leading models of constitutional rights offer no resistance to the notorious slogan: “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.”Footnote 83 Under relativism, the sovereign decides on the exceptions to which rights are subject. Under absolutism, the sovereign decides that what is subject to an exception is not a right. In either case, constitutional rights are incapable of constraining judgments about how public authority should be exercised. Table 3 summarizes the argument in this section.

Table 3 The return of plenary power

| The Role of Moral Reflection | The Vulnerability of Rights | |

|---|---|---|

| The Absolutist Model | Legally unconstrained moral reflection determines the scope of a constitutional right. | Rights may be defined away. |

| The Relativist Model | Legally unconstrained moral reflection determines the strength of a constitutional right. | Rights may be balanced away. |

It is one thing to observe the contemporary world and lament the tendency of regimes to backslide away from arrangements in which constitutional rights regulate public authority. It is quite another to insist, with Bentham, that supreme law rights are incapable of regulating public authority. Here, the difference between the leading contemporary models of constitutional rights consists in the particular path that they take towards Bentham’s conclusion. This convergence raises a crucial question: Is there a method of justifying claims about the scope and strength of rights that does not betray the moral project of rights-based constitutional order by placing persons at the mercy of their government? I return to this question in Section 2.

1.5 Interpretive Strain

The leading models offer opposing answers to the question of how constitutional rights serve external moral goals. Absolutism claims that rights serve these goals with their scope. Relativism claims that rights serve these goals with their strength. When exposed to the routine provisions of modern charters of rights, each claim generates insuperable interpretive difficulties.

From the standpoint of rights relativism, the scope of the right to liberty (or autonomy) envelops every conceivable form of human conduct. Consequently, the general right to liberty renders a host of other constitutional rights redundant:

By definition, the scope of the general right to liberty includes the scopes of all specific liberties. From the fact that one is prima facie permitted to do and not to do as one pleases, it follows that one is prima facie permitted to express or not to express one’s opinion, to choose or reject a certain career, and so on.Footnote 84

Once the scope of liberty is enlarged to include all human conduct, less general rights leave no mark on the constitution’s meaning. Rights relativism “calls into question the necessity of a set of distinct constitutional rights. Nothing would be lost in theory by simply acknowledging one comprehensive prima facie right to personal autonomy instead.”Footnote 85 When actual charters of rights situate the right to liberty among other (often painstakingly formulated) rights, they speak in vain.

Whereas relativists are puzzled by the variety of constitutional rights, absolutists are puzzled by their generality. As we have seen, absolutists insist that the scope of each constitutional right is confined to specific forms of conduct that are “categorically exceptionless.”Footnote 86 This conviction stands in tension with the sweeping terms in which constitutions often formulate rights, protecting, for example, not the freedom to manifest a particular religious belief or practice on a particular occasion, but freedom of religion; not the right to associate with a particular person to advance a particular project, but freedom of association; and so on. The incongruity between the specificity of absolute rights and the generalities in which constitutional rights are formulated raises a dilemma. If constitutional text is taken seriously, one would expect the scope of a right to have some discernible connection to the language in which it is formulated. Absolutists resist this idea because if rights have a broad scope, the demands issued by one right might conflict with the demands issued by another. And if rights impose conflicting demands, then the absolutist claim that each specified right is exceptionless collapses. Alternately, if absolutists insist that constitutional rights have a narrow scope even when they are formulated in broad and sweeping language, then absolutism is open to the charge that it does not take constitutional text seriously.Footnote 87

Absolutists respond to this dilemma by insisting that any right formulated in general terms is not what it seems: “Rights might be stated in general terms … but rights actually are specified, so that the seemingly general right not to be killed, for example, which reads as a right not to be killed full stop, is truly the right not to be killed unjustly.”Footnote 88 Thus, the scope of a constitutional right is determined not by reference to the language in which it is formulated or the distinctive role that the particular right plays in the overarching constitutional framework, but by some independent moral theory that specifies exceptions to the general principle that the constitution affirms. As one absolutist puts the point, the “right to life involves an absolute right not to be killed unless I am threatening someone else’s life, or unless I commit a capital offense, or unless … ”Footnote 89 Wherever rights are formulated in broad and sweeping language, absolutists insist that the constitution does not mean what it says.

Just as relativists and absolutists encounter difficulty making sense of the framing of constitutional rights, so too they have difficulty making sense of limitation clauses.

Absolutism maintains that when the scope of a constitutional right is congruent with what is morally justified, the right is not susceptible to restriction. Accordingly, any restriction of any genuine right is morally unjustified. As a matter of constitutional design, absolutists characterize limitation clauses as “unnecessary” because constitutional rights can achieve justice apart from them.Footnote 90 When the question arises of how extant limitation clauses should be interpreted, absolutists insist that they must be understood as engaging the scope of rights rather than their strength.Footnote 91 On this view, a limitation clause signals that the scope of a constitutional right must be delineated in a morally justifiable manner.

As a general approach to the interpretation of limitation clauses of constitutions and regional and international rights-protecting instruments, the absolutist strategy cannot succeed. The central difficulty is that these clauses often explicitly state that restrictions apply to the scope of rights.Footnote 92 The influential limitation clauses that appear in the German Basic Law, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights indicate that the exercise of rights may be subject to justifiable restrictions or interferences.Footnote 93 These provisions directly repudiate absolutism’s organizing idea that whatever falls within the scope of a right possesses inviolable strength. When confronted by provisions that reject the basic architecture of their model, absolutists insist that these provisions must be disregarded because they employ “uncraftsmanlike language.”Footnote 94 In this way, absolutism arrogates to itself the power to negate a constitutional norm.

In contrast, the relativist model embraces the idea that the restriction of rights may be justifiable. From the relativist standpoint, morality should have a free hand to balance the reasons that support a right in a given context against those that oppose it, and then restrict the right in part or whole as morality demands.

However, relativism has difficulty with actual limitation clauses. For instance, some limitation clauses proscribe any restriction of the core or the essential content of a constitutional right.Footnote 95 Consider, for example, article 19(2) of Germany’s Basic Law: “In no case may the essence of a basic right be affected.”Footnote 96 Robert Alexy, the leading theorist of the relativist model, interprets this provision as follows:

[T]he essential core is what is left over after the balancing test has been carried out. Limitations which correspond to the principle of proportionality do not infringe the essential core, even if they leave nothing left of the constitutional right in an individual case. This reduces the guarantee of an essential core to the principle of proportionality. Since this applies anyways, this would mean that article 19(2) Basic Law simply has declaratory effect.Footnote 97

When confronted by a provision that categorically protects the essence of each right, relativists maintain that the essence of the right is what (if anything) survives balancing in a given context. And since balancing determines the extent to which rights may be restricted in all cases, rights are susceptible to being balanced away in their entirety.Footnote 98 Under relativism, a constitutional provision indicating that the core of each right is immune from restriction has no impact on the constitution’s meaning.

Instead of offering diverging understandings of how each provision within a charter of rights can be given effect, the leading theories of constitutional rights offer opposing visions of how a charter of rights might give effect to some independent moral goal. When these visions conflict with the text of a charter of rights, both camps distort or discard any provision that is inconsistent with their own theoretical commitments. Whichever model one adopts, the line separating constitutional interpretation from constitutional amendment vanishes, and every constitutional provision is rendered insecure. The argument in this section is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4 Interpretive strain

| Constitutional Rights | Limitation Clauses | |

|---|---|---|

| Rights Absolutism | The generality of rights produces interpretive strain. | The defeasibility of rights produces interpretive strain. |

| Rights Relativism | The variety of rights produces interpretive strain. | The indefeasibility of rights produces interpretive strain. |

1.6 Conclusion

The idea that constitutional justification is ordinary moral justification has divided constitutional thought into opposing theories that share the same defects. When one applies this justificatory idea to either the scope or strength of rights, one soon makes three further discoveries. The first is that what constitutional rights require is a matter of legally unconstrained moral judgment. The second is that constitutional rights are powerless to constrain these judgments. The third is that any constitutional provision that impedes the pursuit of an independent moral goal may be distorted or even discarded. The first discovery eviscerates the rule of law, the second resurrects plenary power, and the third denies the authority of constitutional text.

2 Constitutional Justification

In a remarkable article published in 1994, the South African public lawyer Etienne Mureinik expounded the significance of his country’s transition from Apartheid to rights-based constitutional order. He famously characterized the new constitution as a bridge that led away from a “culture of authority” towards

a culture of justification – a culture in which every exercise of power is expected to be justified; in which the leadership given by government rests on the cogency of the case offered in defence of its decisions, not the fear inspired by the force at its command. The new order must be a community built on persuasion, not coercion.Footnote 99

This section explores a single question: What makes a justification cogent?

The two leading theories of constitutional rights, absolutism and relativism, offer the same answer: a justification is cogent when it tracks some moral goal that is fully comprehensible and specifiable apart from constitutional law. From this standpoint, constitutional law has no justificatory resources of its own. Constitutional law remains an empty vessel until it is filled with extrinsic justificatory resources. The previous section explained how this view destroys the rule of law (§1.3), deprives constitutional rights of the power to regulate the exercise of public authority (§1.4), and disregards constitutional text (§1.5).

This section formulates an opposing account of constitutional justification. I argue that rights-based constitutionalism possesses its own justificatory standards, which are neither comprehensible nor specifiable apart from rights-based constitutional order. These standards regulate the resolution of constitutional complaints by distinguishing between two forms of reasoning, one which renders public power accountable to rights and another that places legal subjects at the mercy of their government. Within rights-based constitutional order, a justification is cogent if it is supported by the mode of reasoning that maintains the accountability of all public authorities to rights.

2.1 Two Models of Justification

Attempts to justify claims about the scope or strength of constitutional rights presuppose a more basic question: What is justification? There are two ways of answering this question.

The first is Archimedean. While explaining the power of levers, the Greek mathematician Archimedes supposedly claimed that if he had a firm place to stand, he could move the entire world. This metaphor illustrates a long-standing theory in which justification proceeds by (1) observing some seemingly intractable dispute, (2) identifying a “firm and immoveable” point that lies beyond the dispute’s boundaries,Footnote 100 and (3) appealing to this point to resolve the dispute.Footnote 101 By invoking a “starting point” located some distance from the disputed terrain, Archimedeans purport to offer a critical perspective that its inhabitants fail to observe.Footnote 102 Justification, on this view, involves standing “outside a whole body of belief” and judging it “as a whole from premises or attitudes that owe nothing to it.”Footnote 103

In recent decades, constitutional scholars have increasingly invoked Archimedean justification to resolve enduring debates about what constitutional rights require. When applied to rights-based constitutionalism, Archimedean justification posits a division of labour between morality at large and the constitutional law of a particular jurisdiction. The task of morality at large is to provide a detailed blueprint of what is justified. The task of constitutional law is to give whatever is independently justified the force of supreme law.

The attraction of Archimedean justification lies in its promise to decisively resolve interminable debates about what constitutional rights require. But instead of contracting the domain of disagreement, Archimedean justification extends it in two directions.

First, Archimedean justification generates and perpetuates the dispute between absolutism and relativism. Archimedean justification generates this dispute because its organizing idea – appeal to some external moral referent to determine what constitutional rights demand – is fundamentally ambiguous. As Bentham recognized centuries ago, constitutional rights have two structural features: scope (consisting of the protections that the right affords its bearer) and strength (consisting of the power of the right to withstand opposing considerations). Because Archimedean justification makes no reference to the structure of a constitutional right, it does not indicate which of these structural features stands in need of justification. There are two ways of responding to this ambiguity. One might stipulate that morality imprints its conclusions by delimiting the scope of constitutional rights. Alternately, one might stipulate that morality imprints its conclusions by calibrating the strength of constitutional rights.Footnote 104 The former stipulation culminates in absolutism, while the latter culminates in relativism. The thought here is not that absolutism and relativism happen to affirm Archimedean justification. Rather, Archimedean justification creates absolutism and relativism. These theories are produced by the equivocation that arises when one attempts to apply some freestanding moral theory to the bifurcated structure of a constitutional right.

Once absolutism and relativism emerge, Archimedean justification renders their dispute irresolvable. As we saw in the prior section, there is no basis for privileging either model. Each model is (1) committed to the same conception of justification, (2) equally effective in bringing about any external moral goal, and (3) vulnerable to the same objections.

Archimedean justification invites further disagreement. Once one claims that constitutional rights should bring about some moral goal that can be fully grasped without reference to constitutional law, one must ask: Which independent moral goal should constitutional rights serve? Here Archimedean thought fragments into an array of opposing answers drawn from versions of natural law, the common good, libertarianism, liberalism, conservativism, communitarianism, perfectionism, feminism, utilitarianism, and so on. The result is that judgments about what constitutional rights demand are dragged in opposing directions by those who share the same conception of justification.

Constitutional scholars often conceive of justification in resolutely Archimedean terms. However, Archimedeanism is simply one conception of justification. Its distinguishing idea is that one understands a thing (constitutional rights) in terms of something else (an independent moral goal). The anti-Archimedean alternative lies in the idea that one understands a thing in terms of what it is rather than what it is not.Footnote 105 From the anti-Archimedean standpoint, the justificatory task is not to posit some external moral goal and then treat (either the scope or strength of) constitutional rights as an instrument of its realization, but to identify what is distinctive about rights-based constitutional order and to explore the justificatory ramifications of this distinctiveness.

For those steeped in Archimedean justification, anti-Archimedean justification may seem empty. After all, the call to Understand thing A in terms of thing A is hardly illuminating. Accordingly, Archimedeans sometimes claim that their counterparts are caught in a vicious circle, in which any conclusion merely restates the initial premise, establishing nothing.

This objection is perceptive but not decisive. It is perceptive insofar as anti-Archimedean thought moves in a circles. It is not decisive, however, because not all circles are vicious. Complex systems are comprised of multiple parts. Rights-based constitutional order encompasses a variety of components, including a charter formulating supreme law rights that protect each legal subject; provisions setting out the bases for the justified restriction of rights; institutional roles of legislative, executive, and adjudicative actors in the joint project of rights-protection; constitutional doctrines that determine the scope and strength of rights; constitutional conventions; norms governing constitutional amendments; and so on. Instead of stipulating some external moral goal that one or more of these parts should serve or insisting that each part is intelligible in isolation, anti-Archimedean justification conceives of these parts as components of

an elaborate network, a system, of connected items … such that the function of each item, each concept, could, from the philosophical point of view, be properly understood only by grasping its connections with the others, its place in the system – perhaps better still, the picture of a set of interlocking systems of such a kind.Footnote 106

Within anti-Archimedean thought, justification operates by identifying the parts of a complex whole, expounding the distinctive contribution that each part makes to the whole, and the way in which the whole captures the commonality of the parts. So conceived, anti-Archimedean thought moves in a circle that elucidates the coherent unity that obtains between the general and particular aspects of a thing.Footnote 107 Whether the resulting circle is narrow and empty or wide and illuminating is ultimately “a matter for judgment.”Footnote 108

These opposing conceptions of justification draw our attention towards different questions. Archimedean justification asks: What external moral goal should constitutional rights serve? Should the scope or strength of constitutional rights bring about that goal? In contrast, anti-Archimedean thought eschews reference to external moral goals and instead asks: Is there some moral project that is distinctive to rights-based constitutional order? What constraints does this project impose on judgments regarding the scope and strength of rights? Finally, do these constraints avoid the impasse of constitutional rights?

2.2 Rights-Based Constitutional Order

When constitutional lawyers and judges describe the moral significance of rights-based constitutionalism, they often characterize it as “a real revolution,” a “phenomenal development,” and a “fundamental innovation.”Footnote 109 Underlying these striking statements, I suggest, is the idea that when one abstracts from the variable features of rights-based constitutional orders scattered around the world – their distinctive histories and cultures, the ways in which they formulate rights and limitations, the doctrines that they employ and the holdings that their courts have handed down – what remains is a moral principle apposite to the relationship between rulers and ruled: every public act or omission is to be accountable to the inherent rights of each legal subject. Stated conversely: no legal subject is to be placed at the mercy of a plenary power. Elsewhere I have explored the roots and ramifications of this principle.Footnote 110 Here I can offer only a sketch.

What is a regime of plenary power? And what problem does such a regime raise for the familiar idea that individuals have rights against their government? A regime of plenary power does not necessarily deny that legal subjects have rights against their government. Such a regime might affirm rights held at common law, or pursuant to a statute, or as a matter of widespread political consensus. Nor is a regime of plenary power distinguished by the fact that its acts and omissions result in the systematic violation of rights. What distinguishes a regime of plenary power is its structure. A regime of plenary power is organized in such a way that (some or all) legal subjects are left without a mode of legal recourse through which their inherent rights can be vindicated. The result is that public authorities can violate those rights with impunity.

A regime of plenary power might be organized in different ways. When public authority rests in the hands of a single person (as in a monarchy or autocracy), every person is subject to plenary power. When public authority rests in the hands of the few (as in an aristocracy or oligarchy), the many are subject to plenary power. Finally, when public authority rests in the hands of the many (as in a majoritarian democracy), the few remain subject to plenary power. In each of these arrangements, whether inherent rights are respected and protected depends upon the very party that rights place under obligation. In the absence of legal structures that enable each legal subject to vindicate her rights, public authorities might ignore a complaint alleging the violation of a right, deny that the complaint amounts to a wrong, or concede the commission of a wrong but withhold a corresponding remedy. Accordingly, public authorities remain capable of violating rights with impunity, whether through neglect, persecution, discrimination, or even the extermination of rights-bearers.

The innovation of rights-based constitutionalism consists in the integration of a set of normative, institutional, and doctrinal commitments that are protective of the inherent rights of every person subject to the rule of law. As a normative matter, charters of rights articulate a set of supreme law rights that are to be enjoyed by each legal subject and that bind every public authority. Because these rights are conceived of as legally binding norms rather than mere “political-philosophical declarations,” rights-based constitutionalism requires an institutional structure for their vindication.Footnote 111 This structure enables each legal subject to challenge any public authoritative act or omission that violates any constitutional right by bringing a constitutional complaint to a judicial body that is both accessible to rights-bearers and politically independent. Within rights-based constitutional order, the enjoyment of one’s rights does not depend upon the mere good will or forbearance of the very authorities that rights place under obligation. Finally, as a doctrinal matter, constitutional practitioners in jurisdictions around the world have developed an anti-Archimedean methodology for resolving disputes about the scope and strength of rights. This methodology, I argue in the ensuing sections, avoids the shared defects of the leading models. Together, these normative, institutional, and doctrinal commitments create a form of legal order that does not merely acknowledge that each legal subject has rights that bind all public authority but enables each legal subject to hold every public authority accountable to rights-based standards.

The idea that no person should be at the mercy of a plenary power is a normative abstraction. While this idea distinguishes rights-based constitutional practice from other modes of legal organization, it does not provide a fine-grained blueprint of the various rights that persons possess, the ways in which rights may be limited, the remedies that are available when these rights are impermissibly breached, or the forum in which recourse may be sought. The role of positive constitutional law is not to replicate some perfectly determinate vision of morality, but to specify the abstraction that forms the internal moral goal of rights-based constitutional order.

This specification does not entail uniformity. Different normative and institutional arrangements are capable of rendering public authority accountable to the rights of each legal subject. As a normative matter, when it comes to “concretizing” the scope of basic rights, such as free expression, and their interrelationship with other rights, “a variety of national solutions are compatible with the basic guarantee. Universal recognition of freedom of speech does not require uniform legal solutions or interpretation.”Footnote 112 As an institutional matter, rights-based constitutional order might operate within a legal system that is unitary or federal, unicameral or bicameral, presidential or parliamentary, common law or civil law, and centralized or decentralized in its system of judicial review.

This account of the moral project of rights-based constitutional order cannot be subsumed within an Archimedean justification. As we have seen, Archimedean justification involves the relationship between two elements: an external moral goal and an instrumental means. The moral goal is external to rights-based constitutional order insofar as it can be fully comprehended without reference to it. In turn, rights-based constitutional order is conceived of as an instrumental means insofar as one might ask whether charters of rights in general, or the scope or strength of rights in particular, are the most effective means of realizing the moral goal. If it turns out that rights-based constitutional order is ineffective in serving the relevant moral goal, it may be discarded in favour of a more potent mechanism. Alternately, if rights-based constitutional order turns out to be an effective instrument, its moral significance consists in its causal power to realize some independent moral goal on an industrial scale.Footnote 113

Rights-based constitutional order is not explicable in terms of the relationship between an external moral goal and an instrumental means. As the long history of public law illustrates, in the absence of rights that possess the strength of supreme law, that protect each legal subject, that bind each public authority, and that are justiciable before a politically independent judicial body, certain public authorities retain the power to violate the rights of certain subjects with impunity. Instead of forming an instrumental (or possible) means of rendering the rights of each legal subject enforceable against their government, rights-based constitutional order is the exclusive means through which this moral project may be realized. To the extent that this form of legal organization is absent, the subjection of persons to plenary power prevails.

Turning from means to ends, the aim of ensuring that no person is subject to plenary power stands in a different relationship to rights-based constitutional order than the external moral goals that animate absolutism and relativism. This aim is internal to constitutional law insofar as it has a single domain of application, the constitutional law relationship between rulers and ruled. Beyond this relationship, this aim is “useless and inert.”Footnote 114 It has nothing to say about the moral assessment of human conduct as such. Accordingly, the alternative to conceiving of rights-based constitutional order as a possible means of achieving some independent moral goal lies in the idea that rights-based constitutional order is uniquely capable of making a distinctively constitutional form of moral practice possible.

2.3 The System of Rights

We can now return to our original question: What does it mean to say that a judgment about a constitutional right is justified? Archimedean and anti-Archimedean thought offers different answers to this question.

From the Archimedean standpoint, constitutional justification consists in the conformity of a judgment to some external moral goal – a “brooding omnipresence in the sky.”Footnote 115 Archimedeanism establishes this conformity through a series of stages. The first locates a fixed moral point that is both fully comprehensible and determinate apart from constitutional law. The second stipulates whether the scope or the strength of rights will serve as the instrument of that goal’s fulfillment. The third insists that doctrines that regulate the adjudication of constitutional complaints are either repugnant (insofar as they violate the conclusions that issue from all-things-considered moral reflection) or redundant (insofar as they reproduce the structure of all-things-considered moral reflection). The fourth discards any constitutional provision that stands in the way of any commitment that emerges in the prior stages. In this way, Archimedean justification explains how judgments about constitutional rights might give effect to fully determinate moral conclusions that obtain independently of them.

In contrast, anti-Archimedean constitutional thought does not begin with fully determinate moral conclusions and then insist that constitutional law is a tool for effectuating them. Instead, the anti-Archimedean approach proceeds through a series of stages that move from abstract towards more concrete ideas about the structure and significance of justification within rights-based constitutional order. The first (and most abstract) idea is that rights-based constitutional order requires a comprehensive form of accountability in which each public authority must answer to the inherent rights of each legal subject. This form of accountability is manifested through the constitutional complaint, the practice that distinguishes rights-based constitutionalism from other forms of governance. The second idea is that constitutional complaints must be adjudicated in accordance with a mode of reasoning that actualizes rights-based accountability rather than modes of reasoning that resurrect or perpetuate plenary power. The third idea is that purposive interpretation and proportionality (as conceptualized in the succeeding sections) formulate the sequence of reasons that actualize rights-based accountability. The fourth idea is that the application of these doctrines to the contours of a particular charter of rights enables the justified resolution of constitutional complaints. Accordingly, from the standpoint of anti-Archimedean justification, constitutional judgment does not replicate some determinate moral conclusion about what is all-things-considered justified. Rather, constitutional judgment must resolve constitutional complaints in accordance with the moral considerations apposite to rights-based constitutional order.

In what follows, my aim is to set out the method of justification apposite to the resolution of constitutional complaints. Because this method focuses on the connection of each constitutional norm to every other rather than constitutional norms taken in isolation, I call this method the system of rights. The sections that follow expound the structure of the system of rights by setting out the justificatory constraints that it imposes on judgments that engage the scope and strength of constitutional rights.