Rudi Dutschke is widely recognised as an icon of the German student movement. He took a prominent role in student protests in West Berlin in the mid-1960s and attracted a great deal of media attention with his provocative public statements.Footnote 1 He has featured prominently in the scholarly literature on the German 1968.Footnote 2 He was also, as Quinn Slobodian has observed, ‘one of the earliest and perhaps only German student leader to draw theoretical conclusions from his collaborations with students from the Third World’.Footnote 3 Dutschke does not only feature prominently in early studies of the rise and fall of the German student movement, therefore, but also in more recent research on transnational political campaigns in the ‘Global Sixties’.Footnote 4 First used in the early 2000s, the notion of the Global Sixties describes ‘a new conceptual approach to understanding local change within a transnational framework’.Footnote 5

In 2018, Christina von Hodenberg observed that the literature on the German 1968 has been so obsessed with Dutschke and other members of ‘a male educated elite’ that it has neglected women, workers, the elderly and other key actors.Footnote 6 It is crucial to document these and other experiences, and Hodenberg and others have made important contributions.Footnote 7 Another important project is to re-examine the lives and activities of established protagonists of the student movement like Rudi Dutschke through a critical transnational lens; this essay contributes to that work. Moreover, as I have shown, there is another reason why Dutschke's life still deserves attention: after an assassination attempt in 1968 he was severely disabled and was no longer able to conform to the public image of the fearless (able-bodied) student leader. And yet, he continued to be politically relevant.Footnote 8 This article draws on a transnational approach to analyse events during Dutschke's exile in the United Kingdom in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

At that point in time, the German student movement was in decline, and Dutschke was very ill. The assassination attempt in April 1968 had left him with severe brain injuries and he suffered from panic attacks and social anxiety. He had been admitted to the United Kingdom on a short-term basis to recover from the attack, and his visa was renewed several times on condition that he would not engage in political activity, study for a postgraduate degree at a British university or write for publication. In fact, due to his ill health and unfamiliarity with the British political landscape, Dutschke was neither willing nor able to get involved in politics. However, after a while he and his medical advisors considered it vital to his recovery that he have the opportunity to continue his studies, and in 1970 he was offered a PhD place and requested that the Home Secretary grant him permission to pursue a doctorate in Sociology at the University of Cambridge. His application was declined. This could have been the end of the story, but Dutschke became one of the first aliens to make use of an appeals process that had been introduced by the Wilson government in the late 1960s. The Dutschke case attracted a great deal of media attention and divided the public. In February 1971, he and his family had to leave the country. He died in 1979 in exile in Denmark.

The closed material procedure used in the Dutschke case meant that he, his legal representatives and the public were excluded from a part of the hearing, and critical evidence in the case remained undisclosed. Although intelligence gathered by the British Security Service remains unavailable to this day,Footnote 9 this analysis of the Dutschke case draws on a range of other sources including data from archives in the United Kingdom and in Germany, interviews with contemporary witnesses, and previously unused sources from personal archives. The sources reveal interesting intersections between the student movements in Germany and the United Kingdom in 1968. In Britain, 1968 was the year of a remarkable cataclysm, during which the ‘themes of protest, conflict, permissiveness, and crime begin to run together in one great, undifferentiated “threat”’.Footnote 10 Far from being ‘simply a historical curiosity’,Footnote 11 the Dutschke case powerfully illustrates how two social dynamics at the centre of the ‘moral panic’ in the United Kingdom in the late 1960s – immigration and student protest – were linked and framed as a threat to the nation. Although there was considerable protest against the decision to expel Dutschke from the United Kingdom, his supporters were not able to challenge the new cross-party consensus to ‘clean up’ Britain and to (re)establish law and order that shaped the next decade.Footnote 12

Rudi Dutschke and the Global Sixties

An important factor in the Home Secretary's decision to expel Rudi Dutschke from the United Kingdom was his life and political activity in Germany. There are excellent studies on Dutschke's political ideas and campaigning efforts, which shall be discussed here only briefly.Footnote 13 Born during the Second World War in a rural part of Brandenburg, Germany, Rudi Dutschke grew up in East Germany (the German Democratic Republic; GDR). Although he was a successful athlete and keen learner, his academic performance was negatively impacted by his critical position towards the socialist state.Footnote 14 A Stasi report from 1958 described his political position as ‘extremely unstable’.Footnote 15 Since Dutschke had virtually no chance of pursuing a university degree in East Germany, he moved to West Berlin in 1960 in the hope that he could study there.

In 1960, it was still possible for East German citizens to travel to West Berlin, but this changed with the erection of the Berlin Wall on 13 August 1961. Dutschke was one of thousands of East German citizens who escaped to West Berlin and registered as a political refugee in West Germany (the Federal Republic of Germany; FRG) just before the wall was built. In autumn 1961, he enrolled for a sociology degree at the Free University in West Berlin. At the time, West Berlin was a hotspot for conscientious objectors, young dropouts, aspiring artists and leftist activists from West Germany.Footnote 16 In 1964, Dutschke joined the Socialist German Student League (Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund; SDS) and became a prominent spokesperson of the so-called ‘anti-authoritarian’ wing of the West German student movement. Dutschke and other anti-authoritarians called for a political and organisational alliance between revolutionary movements in the Global South and protest movements in the United States and Western Europe to build a ‘united front’ in the struggle against global imperialism and for ‘a socialist world revolution’.Footnote 17

As Slobodian has shown, by the mid-1960s about 8 per cent of the student population at universities in West Germany were foreign students, and the ideas and tactics of foreign student activists decisively shaped Dutschke's thinking and approach to politics.Footnote 18 In 1964, Latin American, Haitian and Ethiopian students in West Germany set up an international working group with Dutschke and other German student activists in which they discussed anti-colonial struggles and revolutionary theories from the Global South. Dutschke helped to translate Che Guevara's statement ‘Create Two, Three, Many Vietnams’ into German and became a vocal supporter of armed revolutionary movements in Latin America, Africa and Asia. Drawing on Herbert Marcuse, he and other anti-authoritarian student activists argued that nonviolence was usually expected from the oppressed, while the ruling elites reserved their right to use violence.

In the mid-1960s, the Vietnam War became a key area of mobilisation in the West German student movement. Local SDS groups organised information events, study groups, rallies and creative protest actions. In this context, a strategy emerged – ‘limited but open and symbolic overstepping of rules, laws and values in the form of direct actions such as sit-ins or teach-ins’, and was established as a central component of the West German student movement.Footnote 19 One of the first documented encounters between German and British student activists in the 1960s took place in February 1968 at the International Vietnam Congress in West Berlin organised by Dutschke and others. Speakers included the renowned Belgian Marxist economist Ernest Mandel, the Italian publicist Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, the Austrian-born poet and political activist Erich Fried, the prominent American student activist Bernardine Dohrn and two well-known spokespeople of the British student movement: Tariq Ali and Robin Blackburn.Footnote 20

Similar to Dutschke, Blackburn was influenced by the works of Herbert Marcuse and other thinkers associated with the New Left and anti-imperialist and anti-colonial struggles in the Global South. In his speech at the International Vietnam Congress, Blackburn argued that imperialism had to be understood as a global system of violence and had to be confronted by a united anti-imperialist front. He called for action: ‘Claiming the privilege to belong to the revolutionary movement that unites the Vietnamese, the Guatemalan and the Falcon-front guerrilla, means that we have to develop forms of struggle that show that we learn from their experience’.Footnote 21 Blackburn was a frequent contributor to the influential magazine New Left Review and co-editor of the newspaper The Black Dwarf.Footnote 22 Since 1967, his argument had been that ‘British students needed an organization more like that of the American and German SDS’.Footnote 23 Student protests in the United Kingdom tended to be smaller and less confrontational than in West Germany and many other countries and are rarely mentioned in the literature on the global wave of student protests in the long 1960s. However, as Caroline Hoefferle has shown, the British student movement not only influenced UK universities but also UK politics, contributing to the fall of two governments.Footnote 24

In the British media, local student protests were often portrayed as ‘foreigner inspired conspiracies’ and as violent hooliganism.Footnote 25 Against this background, it is hardly surprising that one of the key considerations of the British Home Secretary when it came to assessing Rudi Dutschke's character and subversive potential was his position on violence as a student activist in West Berlin. Of particular interest to the members of the tribunal was a passionate speech Dutschke gave in Amsterdam shortly after the Vietnam Congress in Berlin. Years of campaigning against the Vietnam War had produced no results and when the intensity of fighting reached a new high in early 1968 Dutschke reached the conclusion that more confrontational protest tactics were needed. In Amsterdam, he called for a ‘new terrorism’, by which he meant ‘not terrorism against people but a terrorism against the inhuman [war] machinery’, for example ‘the blowing up of war materials’.Footnote 26 Dutschke's position on violence was characterised by a similar ambivalence to that of Ali, Blackburn and other activists in the United Kingdom.Footnote 27 Whilst expressing support for armed liberation movements in Latin America and other parts of the Third World,Footnote 28 Dutschke rejected calls for violent revolutions in West Germany and other Western states. Like the leftist intellectuals Herbert Marcuse and Jean-Paul Sartre, he considered the use of violence by protesters only legitimate if it was ‘counter-violence’, i.e. a symbolic response to a greater form of violence such as a brutal dictatorship or colonial regime.

His ambivalent stance on violence allowed the British media to portray Dutschke using the stereotype of the dangerous foreign student agitator. But another reason why he was seen as a potential threat was his power to mobilise people. In one of the first detailed British reports about Dutschke, published in the magazine New Christian shortly after the Vietnam Congress in Berlin, he was described as ‘the most magnetic personality of post-war Western society’ and ‘the prophet of revolution’.Footnote 29 The article concluded: ‘in Britain he is just beginning to appear in the papers and television . . . We shall hear much more from Rudi Dutschke, but it may be only too soon that the authorities of the establishment will ask how they can rid themselves of this new prophet of revolution, as they did the first.’Footnote 30 It is questionable whether Dutschke could and should be understood as a ‘prophet’ of revolution, but the article shows that he had a growing international profile. In October 1968, The Black Dwarf published an excerpt from an unpublished book by Dutschke, which reached up to 50,000 readers and made him a household name in the New Left in the United Kingdom.Footnote 31 By then, he and his family were in hiding in Italy.

Less than two months after Dutschke was hailed as the ‘prophet of the revolution’ in the New Christian, a young right-wing extremist tried to kill him in West Berlin. It was nothing short of a miracle that Dutschke survived the assassination attempt. The shooting in April 1968 marks the end of his life as a political refugee and student activist in West Berlin, and the beginning of what his biographer Ulrich Chaussy calls Dutschke's ‘third life’: a life in exile.Footnote 32 Fearing for the safety of her husband and baby son, Gretchen Dutschke tried to find a discreet and quiet place where he could recover. This proved to be more difficult than she had anticipated: journalists managed to locate the Dutschkes even in Italy where they were trying to hide from the media frenzy at a friend's house.

It was probably Erich Fried who proposed to Gretchen that the young family come to England. Fried asked the MP and future Labour leader Michael Mackintosh Foot for help. Foot then sent a letter to the then Home Secretary, James Callaghan, in which he emphasised Dutschke's poor health. The assassination attempt had left Dutschke with long-term physical and psychological damage. His vision was impaired, and he was subject to epileptic fits. One of the hardest things for the once charismatic speaker was that he suddenly suffered from extreme social anxiety and was unable to speak and write. In his letter to Callaghan, Foot stated:

Those assisting him [Dutschke] think that it would be advisable for him to come to London to see a brain specialist and also to avoid some of the publicity he is getting in Rome . . . There is no question of his engaging in any political activity since he is in no condition to do so.Footnote 33

Callaghan granted him a one-month visa to receive medical treatment in the United Kingdom. He made clear that Dutschke's admission ‘would be on the clear understanding that he would not engage in political activities . . . carry out literary commitments, or . . . engage in a course of postgraduate study at a British university’.Footnote 34

Like most foreigners on a short-term visa, Dutschke had to pay for his own medical expenses and was not allowed to claim benefits. Initially he and his family used donations from friends and supporters in Germany and elsewhere to cover their day-to-day expenses. As soon as he felt well enough to do so, Dutschke wanted to complete some book projects that he had been working on with friends prior to the attempt on his life. This, he hoped, would allow him to earn the money he needed to provide for his family. On 22 January 1969, Callaghan gave Dutschke permission to earn money by literary activities. However, he remained adamant that Dutschke must not study at a British university. Retrospectively, Callaghan admitted that he was never prepared to allow Dutschke to study in the United Kingdom and that he considered his application for a student visa proof that his recovery was complete and that he could leave the country.Footnote 35 Rudi Dutschke and his medical advisors argued that his recovery was far from complete and that a postgraduate degree in the United Kingdom would give him the peace and intellectual challenges that he needed to get better.

Dutschke applied for PhD places at Oxford and Cambridge. His application for a research degree at King's College, Cambridge, was assessed by the admissions tutor Bob Young. Because Dutschke had left West Berlin without any formal degree, it was difficult for Young to evaluate his previous academic achievements and suitability for PhD study, but he reached the conclusion that the proposed research project was original and academically rigorous.Footnote 36 Dutschke's application was also assessed by the Board of Graduate Studies at the University of Cambridge. In a letter from 31 July 1970, the Secretary of the Board told Dutschke that his subject of research had been accepted and that he could start his PhD on 1 October if he could produce documentary evidence about his means of financial support. Initially, the offer was for one year only, and was subject to renewal after a progress assessment in the first year. After the board had received a letter confirming that the Swiss ‘Heinrich Heine Foundation’ would pay for his degree, Dutschke's application was formally accepted. All he needed now was a study visa – but his timing was far from ideal.

As previous research has shown, the late 1960s in Britain represented a watershed: the social democratic government's push to use ‘an organised version of consensus’ to govern the United Kingdom was ‘exhausted and bankrupted between 1964 and 1970’.Footnote 37 While many on the left felt that Wilson's liberal reforms did not go far enough, political opponents accused the government of undermining ‘all morality and authority’.Footnote 38 Inspired by Richard Nixon's ‘law and order’ campaign in the United States, the Tories promised in the 1970 election that they would ‘clean up’ Britain, should they come into power. The Tory campaign was a success and marks the beginning of what Hall calls an ‘authoritarian backlash’ in the following decade.

Due to the change of government in 1970, Dutschke's visa application landed on the desk of the new Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling. Hopeful that their compliant behaviour in the United Kingdom and the offer from one of Britain's leading universities might persuade Maudling to grant him a study visa, the Dutschkes left London where they had been staying with friends and moved to Cambridge on 1 August 1970. Initially based at King's College, they moved to a flat at Clare Hall – a graduate college, which offered them more privacy and quiet than King's – on 1 September. Here, Dutschke found an ideal environment for his convalescence and their intellectual ambitions. Gretchen Dutschke remembers the time at Clare Hall as one of the happiest periods of her life.Footnote 39 The flat provided enough space for the four-person family, they got along very well with their neighbours, and they enjoyed the fact that there were shared meals and common spaces in college. Their joy was short-lived, because the Home Office rejected Rudi Dutschke's application for a study visa and ordered him to leave the country. To Maudling's surprise, Dutschke became one of the first aliens to make use of their right to appeal against a decision by the Home Office. Instrumental for Dutschke's appeal against the Home Office was the advice of immigration law expert and ‘sensible radical’ Bob Hepple, a Cambridge graduate and fellow of Clare College.Footnote 40

Dutschke's Appeal against the Home Office

As Dutschke's legal representative Basil Wigoder pointed out, there was a tradition in the United Kingdom ‘to give refuge to people whose political ideas were not those of the majority in this country’ that can be traced back well into the nineteenth century.Footnote 41 Back then, François-Marie Arouet (known under his pen name Voltaire), Peter Alekseyevich Kropotkin, Giuseppe Mazzini, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and other radical political thinkers sought exile in the United Kingdom and were allowed to engage in the same political activities as British citizens. Under the 1905 Aliens Act, foreigners ‘lost the unrestricted right of entry into and residence’ in the United Kingdom.Footnote 42 Since then, the Home Office has had the power to deny foreigners entry into the country and to exclude them on the basis that their presence in the United Kingdom is considered undesirable. Although members of the House of Commons could question decisions taken by the Home Secretary, the 1905 act provided no right of appeal. The First World War led to further restrictions on the rights of aliens in the country and those of foreigners trying to enter the United Kingdom. The 1914 Aliens Registration Act enabled the Home Secretary to restrict the movements of ‘enemy aliens’ in the United Kingdom and to deport them. The Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act 1919 and 1920 Aliens Order extended the provisions in the Aliens Registration Act and gave the Home Secretary the power to expel foreigners in cases where he considered this to be ‘conductive to the public good’.Footnote 43 As Bridget Anderson highlights, emergency legislation from this period ‘was renewed and expanded for over fifty years’.Footnote 44

In the 1960s, political debates about immigration and race in the United Kingdom reached a new level of antagonism and polarisation. After a massive recruitment drive on behalf of the British government in the post-Second World War years, two million immigrants – ‘predominantly from India, Pakistan and the West Indies’ – ‘had settled in the industrial centres around London and the West Midlands’.Footnote 45 This led to considerable discontent among locals and a perceived need for tougher immigration laws. The 1964 general election became the first in which immigration was an issue,Footnote 46 and Tory candidates in the West Midlands used openly racist tactics to attract Labour voters.Footnote 47 On 20 April 1968, the Conservative MP Enoch Powell ‘became both hero and villain to the nation overnight’ with his infamous Rivers of Blood speech in Birmingham against Commonwealth immigration to Britain.Footnote 48 Powell abandoned the cross-party consensus to avoid race from becoming a topic of public controversy, and outlined a scenario in which (white) Britons would soon be outnumbered by immigrants and their descendants. He declared himself to be a spokesman of working-class constituents who were terrorised by Commonwealth immigrants in their neighbourhoods, and claimed: ‘as I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see “the River Tiber foaming with much blood.”’Footnote 49 Although Powell was ostracised in his own party after his Birmingham speech, he received more than 100,000 letters of support and was seen by many as the voice of the ‘silent majority’ in Britain.Footnote 50 As previous studies have shown, ‘“Powellism” was symptomatic of deeper shifts in the body politic’, and put considerable pressure on the ruling Labour government.Footnote 51

The Labour policy on immigration and race in the late 1960s was shaped by tensions and contradictions. In the early 1960s, Labour had opposed restrictions on Commonwealth immigration, but it soon made a U-turn, ‘apparently fearing the electoral unpopularity of a stance which opposed all entry controls’.Footnote 52 Whilst trying to show that it remained committed to racial equality, the Wilson government took active measures to appease the silent majority by curbing Commonwealth immigration, even though it made no attempts to curb Irish immigration and immigration from other predominantly white countries.Footnote 53 The appeals procedure used in the Dutschke case illustrates these tensions and contradictions. In the late 1960s, the Labour government tried to improve administrative practice in immigration cases based on suggestions made by the Wilson Committee (named after its chair Sir Roy Wilson, QC). To eliminate the possibility of abuse of executive power and ‘to give a private individual a sense of protection against oppression and injustice’, the committee proposed the introduction of an appeals process.Footnote 54 With the Immigration Appeals Act 1969 and the Alien (Appeals) Order 1970, the government translated key recommendations of the Wilson Committee report into practice. However, this act, too, came with significant restrictions. In ‘political cases’ the government left the final decision to the Home Secretary.Footnote 55 There were further restrictions to the right of appeal in cases in which the Home Secretary claimed that he had taken a decision in the interests of national security. In such cases, he was under no obligation to disclose evidence and other matters relevant to the case. In addition, appellants and their legal representatives could be excluded from any part of the proceedings. This meant that immigrants now had the right to challenge decisions of the Home Office, but if the Home Secretary considered them potential threats to national security, this right was severely restricted.

The Dutschke case exposed crucial weaknesses in the new appeals policy. It was heard by an Immigration Appeals Tribunal from 17–22 December 1970. In accordance with the law, the five members of the tribunal were chosen by the Lord Chancellor and the Secretary of State – in this case not by the Tory ministers in office (Quintin McGarel Hogg and Reginald Maudling) but by their predecessors in the Labour government (Gerald Austin Gardiner and James Callaghan). The members of the tribunal included two lawyers and two former heads of the Diplomatic Service. The panel was expected to come to a fair and unbiased decision. The ten witnesses who had been invited by Dutschke's legal team (led by Basil Wigoder, QC) were not sworn, but they were cross-examined by the Home Office representative (the Attorney-General Sir Peter Rawlinson). Among the ten witnesses were medical experts, academics from the University of Cambridge and prominent friends and supporters from Germany and the United Kingdom.Footnote 56 Observers and witnesses who were fluent in German and English were shocked by the poor quality of the translations of the German witness statements.Footnote 57 An entire day of hearings took place in camera. On that day, the tribunal discussed evidence presented by Callaghan and by the National Security Service.

The Attorney General and Dutschke's lawyer portrayed the appellant in ways that could hardly have been more different. The former argued that – if allowed to pursue a PhD at a British university – it was inevitable that Dutschke would become a ‘mascot for those who are dedicated to the overthrow of this system’.Footnote 58 In his final statement, Sir Peter Rawlinson claimed that Dutschke:

is a man who in his own country . . . had earned the widest publicity as a notorious leader of demonstrations, some of which involved and some of which led to violence; a man who had in another country, not his own, advocated the burning or physical attack of bases of a military organisation to which United Kingdom forces and the United Kingdom belong; a man who in his writings, which have been put before you, has called for revolution and in certain areas of what is described as the Third World has accepted the need on occasions for the weapon of assassination.Footnote 59

He reminded his listeners that Dutschke had been banned from Holland and France as a result of his political activity, and he insisted that the Home Secretary had no option but to expel Dutschke from the country.

Dutschke's lawyer did not deny that the appellant wanted radical social change on a global scale. Yet he claimed that Dutschke was a decent and honest ‘family man’, who was a ‘revolutionary of a highly individual kind’.Footnote 60 Rather than seeking to overthrow the existing system by violent means, as previous revolutionaries had done, his aim was to bring about change by winning the support of the public. Wigoder urged the tribunal to question the assumption that Dutschke was guilty by association, because some of his friends were involved in political activity and were talking to him about their lives. Wigoder hoped to win the case by appealing to the moral consciousness of the tribunal members and called on them to honour Britain's liberal tradition to act as a safe haven for political dissidents.Footnote 61

The five members of the tribunal paid little attention to moral considerations. When assessing the evidence put before them, they focused on three questions: (1) Was Dutschke's recovery complete? (2) Had he broken his promise not to engage in political activity? (3) Would his doctoral thesis make a significant contribution in his field of research? After assessing a range of evidence and hearing the testimonies of John Arundel Barnes, Professor of Sociology at the University of Cambridge, and of the president of Clare Hall, Professor Alfred Brian Pippard, the tribunal reached the conclusion that Dutschke had the potential to make a significant contribution to the existing literature on the development of the international organisation ‘Communist International’ (Comintern) in the 1920s. However, in the view of the panel members that was ‘not the whole question’.Footnote 62

In its concluding statement on 8 January 1971, the tribunal declared that it supported Maudling's decision to expel Dutschke for three reasons. The first was that the panel members considered Dutschke's convalescence complete. On the second day of the hearing, two medical experts had argued that the appellant should be encouraged to pursue an academic career, because this could help him to improve his speech and reading. Both doctors highlighted that despite his remarkable recovery, Dutschke would be left with permanent disabilities. They also explained that he found it extremely difficult to cope with stress and that his social anxiety increased the risk of epileptic fits. For these reasons, they considered a PhD in the quiet environment of Clare Hall an ideal next step for the appellant. The tribunal rejected this suggestion. Although it acknowledged the need for further treatment and reviews by specialists, it concluded that ‘this can be adequately provided elsewhere than in the United Kingdom and there is therefore in our opinion no essential reason for his [i.e. Dutschke's] continuing to remain in the United Kingdom on medical grounds’.Footnote 63

A second reason why the tribunal supported Maudling's decision is that it considered it had been proved that the appellant had broken his promise not to engage in political activity. In its concluding statement, the panel claimed that the evidence left no doubt that Dutschke ‘has had meetings and discussions with a wide variety of people involved in political activities’ and that ‘these meetings and associations have far exceeded normal social activities’.Footnote 64 This assessment came as a shock to Dutschke and his supporters. At no point had the Home Secretary defined what exactly constituted political activity or given Dutschke any indication that he had engaged in anything but ‘normal social activities’. While the appellant had rejected invitations to get involved in leftist politics in the United Kingdom, e.g. by writing a piece for The Black Dwarf, he considered it a normal social activity to discuss politics with friends.

In its final decision, the tribunal claimed that evidence given in closed hearing had proven that Dutschke's discussions with others were not merely conversations about political activity but constituted a form of political activity.Footnote 65 In its final statement, the panel insisted that ‘planning and organisation can be as important as physical participation in demonstrations and the like’.Footnote 66 Echoing a point made by Maudling, the tribunal argued that Dutschke was ‘exceptionally highly developed politically’ and that it was wrong to make refraining from political activity a condition.Footnote 67 Perhaps surprisingly, the members of the panel did not conclude that Dutschke should be allowed to engage in political activity. Instead, they expressed support for the Home Secretary's decision that Dutschke's continued presence in the United Kingdom was undesirable.

The most striking reason why the tribunal supported Maudling's decision to expel Dutschke was that it regarded him as a potential threat to national security. The panel concluded:

from the evidence presented to us by the Security Service we do not think that up to the present time the presence of the Appellant in this country has constituted any appreciable danger to national security. Nevertheless if he were to remain for a further period as a full-time post-graduate student he would be free from any conditions during that period and we consider that, having regard to all the circumstances of the case, there must without doubt be risk in his continued presence on a longer term stay of this kind.Footnote 68

What – if any – evidence justified the conclusion that there would be a risk in Dutschke's continued presence remains an open question. During the four public days of the hearing, no evidence of it was presented to the tribunal. If there was any, it must have been discussed in camera, leaving the appellant and his legal team with no opportunity to respond. Against this background, it is hardly surprising that the Dutschke case sparked public controversy.

Responses to the Dutschke Case

Newspaper articles, letters, political debates and other sources illustrate that the Dutschke case divided the public. While some regarded the decision in the case unfair and unnecessarily cruel, others considered it a rare success in the battle against foreign extremism. A petition signed by Raymond Williams, Brian Pippard and other academics criticised the tribunal for ‘its failure to distinguish between, on the one hand, study and discussion of political movements, and, on the other hand, political action and organisation’. According to the signatories, this failure was a matter of general concern, because it ‘seriously endangered the conditions of intellectual activity as they are normally understood in this country and its universities’.Footnote 69 In their view, the decision in the Dutschke case was an attack on academic freedom. Based on such a broad understanding of political activity, any critical examination of revolutionary theory, e.g. in the context of a research project on the late works of Karl Marx, and the subsequent discussion of this research project with other academics, could be understood as a form of (revolutionary) politics. And the definition could apply to a range of other contexts as well such as conversations about upcoming elections with work colleagues, or meetings with people who had – at some point of their lives – been involved in political campaigns that the government did not approve of. The New Law Journal described the tribunal's equation of political debate and political activity simply as ‘stupid’.Footnote 70

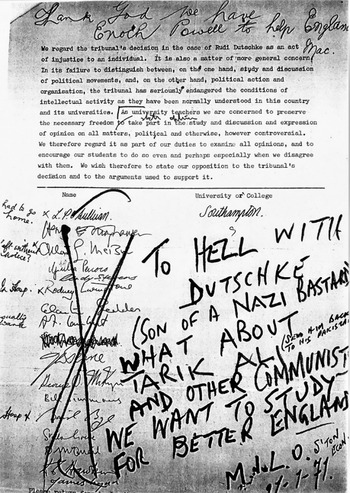

Many others, however, supported the decision to dismiss Dutschke's appeal and demanded the ‘expulsion of all foreign troublemakers’.Footnote 71 An anonymous comment on a petition at the University of Southampton illustrates how the themes of protest, violence and immigration were linked and framed as a threat to the nation (see Figure 1): a derogative comment about Dutschke is combined with the demand to send Tariq Ali back ‘to his Pakistan’ and praise for Enoch Powell (‘Thank God we have Enoch Powell to help England’). In the later 1960s moral panics followed each other at increasing speed, and a ‘general “threat to society” is imputed to them’.Footnote 72 The letters and other statements analysed for this article illustrate that this general threat was perceived by men and women from a range of class backgrounds. Moreover, they confirm the conclusion of earlier studies that ‘people across Britain integrated the immigration issue into broader critiques of the nation in the late 1960s: they were frustrated with the British political system and disgusted by the so-called permissive society’.Footnote 73

Figure 1. ‘To Hell with Dutschke’, copy of petition in the private archive of Professor Ian McConnell.

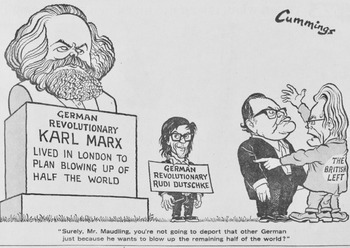

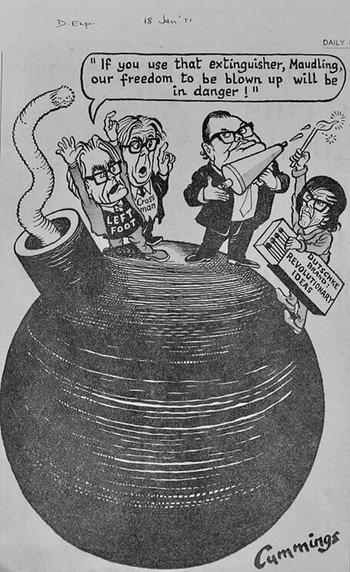

At least in part, the resentment against Dutschke was fuelled by suggestive articles and cartoons in the press. Arthur Stuart Michael Cummings’ cartoons in the Daily Express, for example, portrayed Dutschke as an unshaved wannabe revolutionary (see Figure 2). Although his cartoons indicate that Dutschke could not compete with an intellectual heavyweight like Marx, they suggest that he is dangerous enough to cause considerable political damage if he is not stopped by the Home Secretary (Figure 3).

Figure 2. ‘Surely, Mr. Maudling, you're not going to deport that other German just because he wants to blow up the remaining half of the world?’, Daily Express, 4 Jan. 1971.

Figure 3. ‘If you use that extinguisher, Maudling, our freedom to be blown up will be in danger!’, Daily Express, 18 Jan. 1971.

But there were other voices, too. After Maudling's decision to expel Dutschke had become public, the Dutschkes received dozens of letters in which British citizens distanced themselves from the actions of their government. While some were from individuals and groups with a radical leftist agenda, many were penned by people who did not share Dutschke's political beliefs. One stated:

as a Christian and a liberal, I do not accept your political views, but equally as a Christian, and a liberal (and a Cambridge graduate), I believe completely in your right to hold them and in your right . . . to stay on . . . to do research.Footnote 74

In the eyes of liberal critics, the decision in the Dutschke case constituted a radical departure from the British tradition of tolerance and hospitality, as this letter illustrates:

I am writing to tell you how saddened and shamed I feel at the Home Secretary's decision to expel you from this country. I believe that tolerance is the only virtue in which we lead the world, and I am very sorry that you have not been allowed to enjoy it, and I hope that you will not judge us by the actions of the present Government.Footnote 75

In a letter to the Home Secretary, the academic and novelist John David Caute made a similar point. He wrote: ‘this decision appears gratuitous, unwise and contrary to the best British traditions of tolerance’.Footnote 76

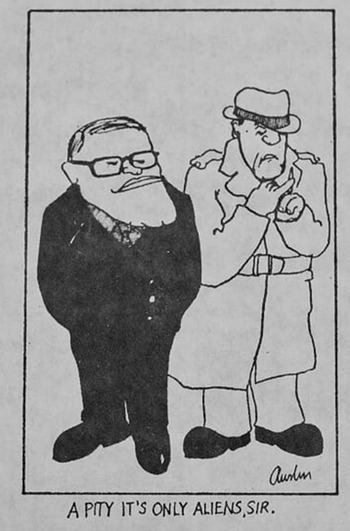

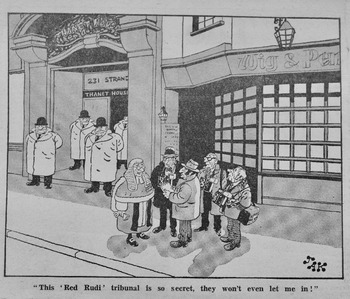

Other critical observers feared that it was only a matter of time until the Home Office used the concept of national security in similar ways against the political opposition in Britain. A cartoon in the Spectator reflects this concern (see Figure 4). Another cartoon criticised the lack of transparency and accountability in the Dutschke case (see Figure 5). As Bob Hepple showed, there was a similar lack of transparency and accountability in the ‘purge’ procedure against civil servants who were suspected of communist or fascist tendencies.Footnote 77

Figure 4. ‘A Pity It's Only Aliens, Sir’, Spectator, 16 Jan. 1971.

Figure 5. ‘This “Red Rudi” tribunal is so secret, they won't even let me in!’, Evening Standard, 23 Dec. 1970

Maudling, however, regarded it as his task as Home Secretary to protect British citizens from domestic threats and from foreign agitators like Rudi Dutschke, and he controversially framed this as a question of national security. On the first day of the hearing, Dutschke's legal representative argued that Maudling had invoked questions of national security after Dutschke's appeal to cover up mistakes in the case. In a debate in the House of Commons on 19 January 1971, the Labour MP Judith Hart made a similar point. She criticised Maudling for redefining ‘national security’ to suit his needs. She claimed that he

has extended – he admits it and supports it – the whole concept of national security from those matters of State secrets, defence secrets and espionage which we have all understood to be encompassed by the necessary methods of State security. The right hon. Gentleman has extended the concept of national security to include political dissent and political militancy, whether or not force is used. He has extended it to cover merely the discussion of what principles should guide militants and dissentients.Footnote 78

When responding to this point, the Home Secretary did not provide a clear definition of national security. Instead, he emphasised the need for a dynamic understanding of the term: ‘there can be no doubt that the concept of national security has been changing as the threat to our democratic society changes’.Footnote 79

In January 1971, Maudling proposed a change to the immigration appeals procedure that enabled the Home Secretary to define security in broader terms and to assess whether immigrants could be considered a threat to national security. Essentially, the Home Secretary wanted the right to ‘ban more “Dutschkes”’ without having to bother with further appeals.Footnote 80 The 1971 Immigration Act made Maudling's wishes come true. Although there was still a right to appeal, it was drastically limited in cases in which the Home Secretary certified ‘that the appellant's departure from the United Kingdom would be conducive to the public good, as being in the interests of national security or of the relations between the United Kingdom and any other country or for other reasons of a political nature’.Footnote 81

A similar procedure has been used in hundreds of other cases where disclosure is considered damaging to the interests of national security. According to David Bonner, ‘the most famous case of the 1970s’ was that of two American journalists: Philip Agee and Mark Hosenball.Footnote 82 After quitting his job as Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officer, Agee moved to London with his family, where he published a book revealing the identity of hundreds of CIA officers and other agents working for the United States. While some argued that Agee had blown the whistle on the CIA out of moral considerations, others saw him as a traitor who ‘did everything he could to endanger his colleagues and fellow American citizens’.Footnote 83 Since Hosenball's case was linked to that against Agee, the Home Secretary refused to provide any details of the allegations against him. In debate in the House of Commons, the Labour MP Phillip Whitehead queried whether Hosenball was ‘not in precisely the position of Mr. Rudi Dutschke about five years ago when the position was very rightly criticised from our side of the House?’. Indeed, there are striking parallels: in both cases the appellants made use of their right to appeal but the Home Secretary refused to share critical details with them, their legal representatives and the public. Like the Dutschke Tribunal, the Agee-Hosenball case received a great amount of media attention, sparked critical debates about justice and security, and provoked calls for legal reform.Footnote 84 The fact that these and other laws restricting the rights of ‘undesirable’ foreigners remained in force despite this criticism is indicative of the significant force of the authoritarian backlash in the 1970s.

Conclusion

Britain had a long liberal tradition of granting refuge to political dissidents. However, as this article shows, this changed in the long 1960s. In the United Kingdom, this period not only saw the first systematic attempts to curb Commonwealth immigration but also new restrictions on the rights of students and other foreigners whose presence was considered undesirable for political reasons. The prominent German student activist Rudi Dutschke was one of the first aliens to make an appeal against the Home Office after being told that he was considered a potential threat to national security. The definition of national security used in this case was as broad as the perceived threat to society in the late 1960s. Despite vocal protest by liberal and leftist critics, Dutschke's appeal was dismissed, and the early 1970s saw further restrictions to the appeal rights of foreigners whose presence in the United Kingdom was considered undesirable for political reasons.

Dutschke, like some other student activists in Germany, France and the United Kingdom, had an ambivalent attitude to violence. However, it is unlikely that British authorities regarded him as a threat purely because of his position on violence. As this article shows, he had exchanged ideas with Tariq Ali, Robin Blackburn and other British activists prior to his arrival to the United Kingdom, and Ali and Blackburn had already publicised many of these ideas via The Black Dwarf and other leftist publications. More likely, Dutschke was seen as a threat because he was associated with three themes that were key components of the moral panic in Britain in the late 1960s: violence, protest and immigration. Maudling knew that he had the support of the silent majority (and parts of the political opposition) when expelling this ‘foreign troublemaker’. Far from being merely a footnote in the history of the Global Sixties and the history of immigration policy in the United Kingdom, the decision in the Dutschke case can be seen as one of the first telling signs of the ‘authoritarian backlash’ in the 1970s.

In recent years, the concept of national security has been extended even further. The Justice and Security Act 2013 empowers British courts to use closed material procedures in a wide range of cases in which it ‘would be damaging to the interests of national security’ to disclose evidence to legal adversaries or the media.Footnote 85 As with the Immigration Appeals Act 1969 and the Alien (Appeals) Order 1970, the Justice and Security Act was met with criticism and opposition.Footnote 86 Yet this did not stop the government from passing the bill, thereby extending the use of the deeply problematic procedure used in the Dutschke case and other immigration tribunals ‘across the civil courts in cases deemed to involve national security’.Footnote 87

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Gretchen Dutschke, Cary Parker, Quinn Slobodian and the three anonymous reviewers for their encouragement and useful feedback.