Introduction

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been widely adopted by psychiatry in recent years, but its increase in use in the severe disorders of schizophrenia, major depression and bipolar disorder is particularly noteworthy. This is because it challenges what has, until recently, been a dominance of biological approaches to these disorders. Thus, although contemporary accounts of schizophrenia (e.g. Picchioni & Murray, Reference Picchioni and Murray2007) emphasize biological factors in its aetiology and consider neuroleptic drugs to be the mainstay of treatment, official UK treatment guidelines from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) also state that psychological interventions are indispensable and that CBT should be offered to all patients (NICE, 2003, 2009). Psychological factors may loom larger in the aetiology of major affective disorder, but when it comes to treatment, the emphasis in the literature, particularly in bipolar disorder, has once again been firmly on pharmacotherapy. Attitudes may be changing here too, however. References to the effectiveness of CBT are pervasive in the UK depression treatment guideline (NICE, 2004); a government initiative is under way in the UK to provide CBT for depression and anxiety in 250 dedicated therapy centres (Layard, Reference Layard2006); and CBT is being advocated for relapse prevention in bipolar disorder (e.g. Scott & Colom, Reference Scott and Colom2005; Basco & Rush, Reference Basco and Rush2007).

Nevertheless, a cursory look at the literature reveals well-conducted trials where CBT has had negative findings in all three disorders. For example, large-scale trials of CBT in schizophrenia have failed to find significant advantages over befriending (Sensky et al. Reference Sensky, Turkington, Kingdon, Scott, Scott, Siddle, O'Carroll and Barnes2000) or supportive counselling (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tarrier, Haddock, Bentall, Kinderman, Kingdon, Siddle, Drake, Everitt, Leadley, Benn, Grazebrook, Haley, Akhtar, Davies, Palmer, Faragher and Dunn2002). In depression, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) study of brief psychotherapeutic interventions found only marginal evidence for the effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy and none for cognitive therapy (Elkin et al. Reference Elkin, Shea, Watkins, Imber, Sotsky, Collins, Glass, Pilkonis, Leber, Docherty, Fiester and Parloff1989). A recent large trial of CBT for prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder found no advantage over treatment as usual (TAU) (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Paykel, Morriss, Bentall, Kinderman, Johnson, Abbott and Hayhurst2006). In fact, the perceived efficacy of CBT in all three disorders seems to rest principally on meta-analysis, where it has been concluded, for example, that: ‘The positive results … can therefore be taken as confirming the promise of cognitive behavioural treatment in schizophrenia’ (Pilling et al. Reference Pilling, Bebbington, Kuipers, Garety, Geddes, Orbach and Morgan2002); ‘cognitive therapy has been demonstrated effective in patients with mild or moderate depression and its effects exceed those of antidepressants’ (Gloaguen et al. Reference Gloaguen, Cottraux, Cucherat and Blackburn1998); and ‘the use of psychological therapies as an adjunct to medication [in bipolar disorder] is likely to be clinically and cost effective’ (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Colom and Vieta2007).

A feature of these and other meta-analyses, however, is the lack of consideration they have given to bias caused by lack of blinding and the failure to use a control intervention. For example, out of seven meta-analytical reviews of CBT for schizophrenia (Gould et al. Reference Gould, Mueser, Bolton, Mays and Goff2001; Rector & Beck, Reference Rector and Beck2001; Pilling et al. Reference Pilling, Bebbington, Kuipers, Garety, Geddes, Orbach and Morgan2002; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Cormac, Silveira da Mota Neto and Campbell2004; Tarrier & Wykes, Reference Tarrier and Wykes2004; Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Favrod, Trieu and Pomini2005; Wykes et al. Reference Wykes, Steel, Everitt and Tarrier2008), only two (Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Favrod, Trieu and Pomini2005; Wykes et al. Reference Wykes, Steel, Everitt and Tarrier2008) examined the influence of blindness on effect size, and neither of these attempted to establish the treatment's effectiveness in trials that used both blinding and a control intervention. Nor was blindness addressed in either of the two benchmark meta-analyses of CBT for depression (Gloaguen et al. Reference Gloaguen, Cottraux, Cucherat and Blackburn1998; Churchill et al. Reference Churchill, Hunot, Corney, Knapp, McGuire, Tylee and Wessely2001). The way in which CBT was compared against other psychological interventions in Gloaguen et al.'s (Reference Gloaguen, Cottraux, Cucherat and Blackburn1998) meta-analysis has also been criticized (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Roy and Eyers2003).

Noting that there is increasing evidence that inadequate quality of trials can translate into biased findings of systematic reviews in health care, Jüni et al. (Reference Jüni, Douglas, Altman and Egger2001) recommended that the influence of study quality should be examined routinely. They also argued that it is preferable to do this by examining the influence of key components of methodological quality individually rather than by means of summary scores from quality scales, which are problematic for several reasons. This meta-analysis therefore examines the effectiveness of CBT in studies that have attempted to guard against two of the most familiar and important sources of bias in treatment trials, lack of blinding and failure to use a control intervention.

Method

We included studies that examined the effectiveness of CBT in adults (i.e. not adolescents or elderly subjects) meeting any diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia (some of which also allowed patients with schizo-affective disorder and delusional disorder), major depression or bipolar disorder. CBT was defined as an intervention whose core elements include the recipient establishing links between their thoughts, feelings and actions and target symptoms; correcting misperceptions, irrational beliefs and reasoning biases related to these target symptoms, involving monitoring of one's own thoughts, feelings and behaviours with respect to the symptom; and/or the promotion of alternative ways of coping with target symptoms.

The studies were required to use a control intervention that the study investigators either explicitly considered not to have specific therapeutic effects or which might reasonably be regarded as lacking these (e.g. supportive therapy, psycho-education, relaxation). We also included studies comparing CBT to pill placebo (which have only been carried out in major depression). Blindness of evaluations was not specified as a requirement for inclusion, but was examined as a moderator variable. In keeping with the general approach of meta-analysing methodologically rigorous trials, we did not include studies with small sample sizes (<10 participants in either group) or studies that were identified by the authors as pilot studies. Excluded studies are given as Supplementary material (available in the online version of the paper).

We also meta-analysed studies of CBT for prevention of relapse, even though many of these used TAU as the comparison condition rather than a control intervention. This was on grounds that (a) relapse is a relatively objective outcome measure that should be robust to the effects of subject and observer bias; and (b) relapse prevention has been a major focus of studies of CBT in depression and constitutes the only type of study that has been carried out in bipolar disorder. Nevertheless, we also examined the use of TAU or a control intervention as a moderator variable, where possible, in these studies. To be included, studies had to use a symptomatic definition of relapse, rather than simply equating this with rehospitalization, and had to define relapse according to predetermined criteria.

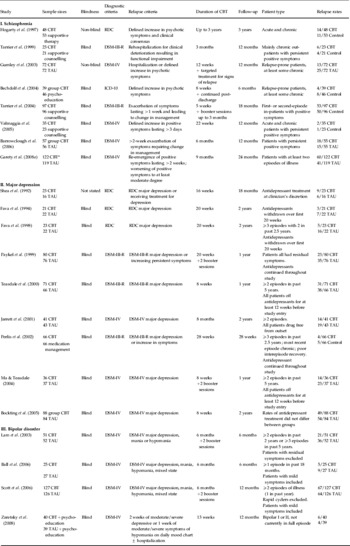

Studies were searched using existing comprehensive meta-analyses of CBT for schizophrenia (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Cormac, Silveira da Mota Neto and Campbell2004), depression (Gloaguen et al. Reference Gloaguen, Cottraux, Cucherat and Blackburn1998; Churchill et al. Reference Churchill, Hunot, Corney, Knapp, McGuire, Tylee and Wessely2001; Vittengl et al. Reference Vittengl, Clark, Dunn and Jarrett2007) and bipolar disorder (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Colom and Vieta2007), supplemented by electronic searches of the literature (Medline, EMBASE and PsycINFO). For the electronic search, we chose inception dates of 5 years before the publication of the earliest of the above meta-analyses, which would have captured earlier studies. The search was conducted up to the end of January 2009. Review articles and the reference lists of all obtained papers were checked, as were research databases for trials. Only published studies were included. There were no restrictions on year of publication or language. Tables A1 and A2 in the Appendix provide details on the included studies.

Data were synthesized using standard meta-analytical techniques. Studies comparing the effect of CBT against a control intervention were pooled from continuous measures (i.e. symptom scores) using an effect size measure, Cohen's d (Hedges' correction was used). The end-point was the end of the acute treatment phase as defined by the investigators. In line with common meta-analytical practice, effect sizes obtained from a range of different symptom rating scales were pooled; we did not attempt to carry out separate analyses for the different scales, unless there were fundamental conceptual differences between them (e.g. self-rated versus observer-rated). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for relapse rates. Fixed-effects analysis was used in both cases (random effects analyses gave similar results). Intention-to-treat analysis was used if relevant data were available (typically in relapse studies) or, if not, on the numbers remaining at the end of the study period. Two of the investigators extracted effect sizes and ORs by consensus. All results were checked twice. Heterogeneity was assessed by means of the Q-statistic.

Results

Schizophrenia

Effectiveness on symptoms

Nine trials were found. We excluded two studies of first-episode psychosis (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, McGorry, Killackey, Bendall, Allott, Dudgeon, Gleeson, Johnson and Harrigan2008; Lecomte et al. Reference Lecomte, Leclerc, Corbière, Wykes, Wallace and Spidel2008) because they both contained a high proportion of patients (>20%) with affective psychotic diagnoses. The studies were carried out on both acute and chronic patients and the period of treatment ranged from 5 weeks to 9 months. The control interventions used were supportive counselling/supportive therapy (n=5), befriending (n=1), group psycho-education (n=1), recreational therapy (n=1) and social activity therapy (n=1). Two were open studies and seven were carried out under blind conditions. Several studies did not provide overall symptom scores but instead gave separate scores for positive and negative symptoms (and sometimes disorganization or general psychopathology). To maximize the number of usable studies, therefore, a combined effect size for all symptoms for each study was first calculated by averaging the effect sizes for these symptoms (this was done using the individual effect sizes and standard errors, using a random effects model and testing for homogeneity in each case). Effects on positive and negative symptoms were then examined separately.

The findings are shown in Fig. 1. The pooled effect size was −0.08 [95% confidence interval (CI) −0.23 to +0.08, p=0.34] (the negative sign favours CBT). The studies were not significantly heterogeneous [Q(8)=9.28, p=0.32]. As Fig. 1 suggests, the two non-blind studies had a significantly larger pooled effect size than the seven blind studies (−0.63 v. 0.00) [QB(1)=6.38, p=0.01]. Dividing studies into those carried out on acute patients (n=1), mixed or unspecified patients (n=6) and chronic patients (n=2) did not reveal differences [effect size +0.10, −0.17 and −0.04 respectively, QB(2)=1.82, p=0.40]. The overall effect size was increased only slightly by excluding the single study that used a group therapy form of CBT (Bechdolf et al. Reference Bechdolf, Knost, Kuntermann, Schiller, Klosterkotter, Hambrecht and Pukrop2004) (effect size for eight studies=−0.11, 95% CI −0.29 to +0.06, p=0.19).

Fig. 1. Studies of the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) against symptoms in schizophrenia (* indicates blind study).

Eight studies reported findings for positive symptoms and seven for negative symptoms. The pooled effect size for positive symptoms was −0.19 (95% CI −0.37 to −0.02, p=0.03), favouring CBT. Once again, however, the result was moderated by blindness: the effect size in the six blind studies was −0.08 compared to −0.87 in the two non-blind studies [QB(1)=9.28, p=0.002]. The pooled effect size for negative symptoms was −0.02 (95% CI −0.22 to +0.18); here, blindness did not moderate the effect size [effect size for five blind studies +0.04 v. −0.26 for two non-blind studies, QB(1)=1.36, p=0.24].

Effectiveness against relapse

Eight studies were found. These had follow-up periods of 6 months to 3 years. We did not include two studies (Drury et al. Reference Drury, Birchwood and Cochrane2000; Turkington et al. Reference Turkington, Sensky, Scott, Barnes, Nur, Siddle, Hammond, Samarasekara and Kingdon2008) because there was a 5-year interval between treatment and assessment during which there was no intervention or evaluation. Three of the studies compared CBT against TAU, and five included comparison groups of supportive counselling. Six rated relapse under blind conditions and two under non-blind conditions. The studies defined relapse in terms of increases in positive symptoms, usually requiring that the increase lasted a specified period and sometimes with a requirement of hospitalization or change in management (see Appendix).

The findings are shown in Fig. 2. The pooled OR for these studies was 1.17 (95% CI 0.88–1.55, p=0.29), non-significantly favouring TAU. The studies were not significantly heterogeneous [Q(7)=11.89, p=0.10]. Blindness moderated the effect size at trend level [OR for six blind studies 1.35 v. 0.72 for two non-blind studies, QB(1)=3.28, p=0.07]. However, use of control intervention was not a significant moderating factor [QB(1)=0.02, p=0.89]. Once again, there was nothing to suggest that inclusion of studies using group CBT was influencing the result [OR for six studies using individual CBT 1.12 v. 1.01 for two studies using group CBT, QB(1)=0.20, p=0.66].

Fig. 2. Studies of the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in reducing relapse in schizophrenia (* indicates blind study).

In the study of Garety et al. (Reference Garety, Fowler, Freeman, Bebbington, Dunn and Kuipers2008a) we analysed relapse data in patients who had made a full or partial recovery. However, Garety et al. (Reference Garety, Fowler, Freeman, Bebbington, Dunn and Kuipers2008b) have argued that these rates do not reflect the true intention-to-treat effect because patients were randomized to CBT or TAU while they were ill; some failed to recover (CBT, n=9; TAU, n=18) and so did not have the opportunity to relapse. Adjusting the total numbers for CBT and TAU to include patients who were randomized but did not recover made little difference to the pooled OR (1.20, 95% CI 0.91–1.59, p=0.19).

Major depression

Effectiveness against symptoms

Ten studies were found. These all excluded patients with bipolar disorder or psychotic depression. Six of the studies compared patients against a control psychological intervention and four against pill placebo. The studies all measured symptoms using the observer-rated Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) or the self-rated Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), or both. Because the former scale is observer rated and the latter a self-rating questionnaire, we meta-analysed data from these scales separately.

Figure 3 shows the result for the nine studies using the HAMD. The pooled effect size was −0.28 (95% CI −0.45 to −0.12, p=0.001), significantly favouring CBT. The studies were not heterogeneous [Q(8)=9.40, p=0.31]. The effect size was significantly greater in the four studies comparing CBT to pill placebo than in the five comparing it to control psychological intervention [−0.41 v. 0.00, QB(1)=4.94, p=0.03]. Blindness of evaluations did not significantly moderate the effect size in these studies [pooled effect size for five blind studies −0.39 v. −0.16 in three non-blind studies; QB(1)=1.00, p=0.32] (the study of Scott and Freeman, Reference Scott and Freeman1992 was excluded from this analysis because of uncertainty over whether blindness had been maintained).

Fig. 3. Studies of the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) against symptoms in major depression (* indicates blind study).

The pooled effect size for the eight studies using the BDI was similar at −0.27 (95% CI −0.45 to −0.08, p=0.004). Use of psychological control intervention (five studies) or pill placebo (three studies) did not moderate the effect size in these studies (−0.27 v. −0.27). The BDI is a self-rated scale and so none of these studies could be considered blind.

Effectiveness against relapse

Nine studies were included. We excluded four studies (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Hollon, DeRubeis, Piasecki, Grove, Garvey and Tuason1992; Hollon et al. Reference Hollon, DeRubeis, Shelton, Amsterdam, Salomon, O'Reardon, Lovett, Young, Haman, Freeman and Gallop2005; Segal et al. Reference Segal, Kennedy, Gemar, Hood, Pedersen and Buis2006; Dobson et al. Reference Dobson, Hollon, Dimidjian, Schmaling, Kohlenberg, Gallop, Rizvi, Gollan, Dunner and Jacobson2008) because of systematic bias: the patients in the control group, but not those in the CBT group, had been treated with antidepressant medication until immediately before withdrawal at the start of the study, so potentially increasing the risk of depressive relapse in this group. All but one of the studies compared CBT to TAU (Perlis et al. Reference Perlis, Nierenberg, Alpert, Pava, Matthews, Buchin, Sickinger and Fava2002 compared it to pill placebo), and in all but one cases relapse was determined by an assessor who was blind to allocation. Relapse was typically defined as development of symptoms meeting diagnostic criteria for major depression; however, three studies allowed a supplementary criterion based on development of depressive symptoms exceeding a predetermined threshold but not meeting criteria for major depression (Shea et al. Reference Shea, Elkin, Imber, Sotsky, Watkins, Collins, Pilkonis, Beckham, Glass, Dolan and Parloff1992; Paykel et al. Reference Paykel, Scott, Teasdale, Johnson, Garland, Moore, Jenaway, Cornwall, Hayhurst, Abbott and Pope1999; Perlis et al. Reference Perlis, Nierenberg, Alpert, Pava, Matthews, Buchin, Sickinger and Fava2002).

The studies are summarized in Fig. 4. The pooled OR was 0.53 (95% CI 0.40–0.71, p<0.001). The studies were not significantly heterogeneous [Q(7)=8.60, p=0.38]. All, or nearly all, of the studies were blind (blindness was not commented on in the study of Shea et al. Reference Shea, Elkin, Imber, Sotsky, Watkins, Collins, Pilkonis, Beckham, Glass, Dolan and Parloff1992), and all but one (Perlis et al. Reference Perlis, Nierenberg, Alpert, Pava, Matthews, Buchin, Sickinger and Fava2002) compared CBT to TAU. Therefore, these moderating variables were not examined.

Fig. 4. Studies of the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in reducing relapse in major depression (* indicates blind study).

In two studies patients in both groups remained on antidepressant medication throughout the follow-up period, whereas in five, both groups were withdrawn from medication either before study entry or within the first 20 weeks of a 2-year follow-up (in the other two studies some patients in both groups were treated). The pooled ORs for studies on treated and untreated patients were 0.52 and 0.45 respectively [QB(1)=0.17, p=0.67].

Bipolar disorder

Effectiveness against relapse

There were no includable trials of CBT as a treatment for acutely ill patients. Four controlled trials of CBT for prevention of relapse have been carried out and are shown in Fig. 5. They all compared CBT to TAU and the assessments were all made under blind conditions. In three of the studies relapse was defined as development of symptoms sufficient to meet diagnostic criteria for major depression, mania, hypomania, or a mixed state; the fourth required a defined period of moderate/severe or incapacitating depressive or manic symptoms. The pooled OR for the four studies was insignificant at 0.78 (95% CI 0.53–1.15, p=0.22).

Fig. 5. Studies of the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in reducing relapse in bipolar disorder (* indicates blind study).

Discussion

Studies of psychological therapies in major psychiatric disorder have not used, and perhaps will never be able to use, precisely the same methodology as that used to establish the efficacy of drug treatments, namely the double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. However, when those studies whose design approximates to this methodology are reviewed, their findings are at variance with the conclusions expressed in review articles, meta-analyses, editorials and even government documents.

The contrast is at its starkest in schizophrenia. In a recent editorial, Kingdon (Reference Kingdon2006) stated: ‘More than 20 randomized controlled trials and five meta-analyses have shown cognitive behaviour therapy to be beneficial in schizophrenia, reducing both positive and negative symptoms during therapy and beyond.’ Yet pooling the results of nine trials comparing CBT to non-specific control interventions reveals no indication of effectiveness. Nor does meta-analysis of a similar-sized body of evidence of CBT for relapse prevention yield any evidence of an effect. CBT for schizophrenia thus finds itself in the unusual position of being recommended in the revised NICE guideline (NICE, 2009), despite having failed in all of the treatment studies that used both control interventions and blind evaluations, and after the authors of the largest trial of relapse prevention (Garety et al. Reference Garety, Fowler, Freeman, Bebbington, Dunn and Kuipers2008a) concluded that ‘generic CBT for psychosis is not indicated for routine relapse prevention in people recovering from a recent relapse of schizophrenia.’

It could be objected that our meta-analysis of positive symptom scores revealed a small but significant effect size [−0.19 (95% CI −0.37 to −0.02), p=0.03] in favour of CBT. However, this advantage seemed clearly to reflect the lack of blindness of two of the trials; CBT showed no evidence of effectiveness against positive symptoms in the pooled results from six trials that used both control interventions and blind evaluations. Another ground for appeal might be that one relatively large study of the effectiveness of CBT in schizophrenia (Sensky et al. Reference Sensky, Turkington, Kingdon, Scott, Scott, Siddle, O'Carroll and Barnes2000) found that, although CBT was no better than a control intervention of befriending at the end of the 9-month treatment period, it did show a significant advantage at follow-up a further 9 months later. However, delayed or enduring effects have not been observed in other studies (Tarrier et al. Reference Tarrier, Wittkowski, Kinney, McCarthy, Morris and Humphreys1999, Reference Tarrier, Lewis, Haddock, Bentall, Drake, Kinderman, Kingdon, Siddle, Everitt, Leadley, Benn, Grazebrook, Haley, Akhtar, Davies, Palmer and Dunn2004), and the most recent meta-analysis (NICE, 2008) found effect sizes for CBT against ‘active controls’ (mainly non-specific control interventions, but in one case cognitive remediation therapy) of only −0.18 (95% CI −0.39 to +0.03, five studies) at 12-month follow-up and −0.08 (95% CI −0.40 to +0.24, three studies) at 24 months.

A final objection could be that, in the meta-analysis of relapse rates, we did not include studies that used hospitalization as an index of relapse. This decision excluded a large study which found that CBT significantly reduced the rate of subsequent hospitalization in schizophrenia (Turkington et al. Reference Turkington, Kingdon, Rathod, Hammond, Pelton and Mehta2006). The NICE (2009) meta-analysis of this and four other studies also found a significant advantage for CBT in reducing rehospitalization (relative risk 0.76, 95% CI 0.61–0.94). Nevertheless, hospitalization is not the same thing as relapse; the decision to admit a schizophrenic patient depends not only on their clinical status but also on considerations of whether there is support outside hospital, whether the patient is likely to comply with treatment at home, etc., judgements of which could be influenced by knowledge that he or she is in the active treatment arm of a trial. Indeed, the fact that Turkington et al.'s (Reference Turkington, Kingdon, Rathod, Hammond, Pelton and Mehta2006) trial, where hospitalization was the outcome measure, and Garety et al.'s (Reference Garety, Fowler, Freeman, Bebbington, Dunn and Kuipers2008a) similarly large trial, where relapse was the outcome measure, had such completely contradictory results attests to the reality of the difference between these two measures.

However, CBT does emerge from our meta-analytical review as an effective treatment for major depression, both as a treatment for acute symptoms and for relapse prevention. Nevertheless, there is a qualification to this conclusion: at 0.28 (HAMD) and 0.27 (BDI) the pooled effect size for the acute treatment studies was in the small range, implying only modest therapeutic benefit. These findings bear comparison with those of the most exhaustive meta-analysis of psychological treatments for depression to date, the National Health Service (NHS) R&D Health Technology Assessment systematic review of brief psychological treatments for depression (Churchill et al. Reference Churchill, Hunot, Corney, Knapp, McGuire, Tylee and Wessely2001). This found that all of a range of psychotherapeutic interventions showed significant advantages when compared to TAU or a waiting list control. CBT was also found to be significantly superior to supportive therapy. However, here the authors went on to state: ‘The overall quality score of the trials appeared to have a considerable effect on recovery and mean differences, with lower-scoring trials demonstrating a pronounced and highly significant difference and higher-scoring trials demonstrating no significant differences.’ Perhaps, more than anything else, our review makes it clear that a large, methodologically rigorous trial comparing CBT to a non-specific control intervention in depression, similar to the several that exist in schizophrenia, has yet to be carried out. We were able to find only five such studies, all of which were small and only one of which was carried out under blind conditions. This might be considered a somewhat slender evidence base on which to introduce 250 treatment centres providing CBT for depression and anxiety across the UK.

For understandable reasons, little work has examined the usefulness of CBT in patients who are acutely manic or hypomanic. However, pilot studies (Lam et al. Reference Lam, Bright, Jones, Hayward, Schuck, Chisholm and Sham2000; Scott et al. Reference Scott, Garland and Moorhead2001) gave grounds for optimism for its use in relapse prevention. Three out of the four formal trials then went on to find no significant advantage for CBT, including one with very large numbers (n=253). Meta-analysis of these trials supports the conclusion that this form of psychological therapy is ineffective in preventing relapse in bipolar disorder.

A certain amount of ambiguity concerning the nature of control interventions is evident in the meta-analytical literature on CBT. Sometimes the term ‘active control’ is used (e.g. NICE, 2009), with the implication, not always correct, that, similar to how the term is used in drug studies, the therapy is being compared against an intervention that also has established therapeutic benefits. In other meta-analyses, a strategy is adopted of evaluating CBT systematically against a range of different therapies, some of which, such as relaxation and supportive counselling, would be expected to have little or no therapeutic effect, whereas others, such as psychodynamic therapy, have clear therapeutic aims (e.g. Churchill et al. Reference Churchill, Hunot, Corney, Knapp, McGuire, Tylee and Wessely2001; Cuijpers et al. Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Andersson and van Oppen2008). However, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that we only included studies using control interventions that lacked any specific therapeutic effect. Thus, for example, Sensky et al. (Reference Sensky, Turkington, Kingdon, Scott, Scott, Siddle, O'Carroll and Barnes2000) described befriending as a non-specific control intervention, whose benefits for people with schizophrenia do not have any underlying theoretical or empirical basis, where the sessions focused on neutral topics, such as hobbies, sports and current affairs, and in which psychotic or affective symptoms were not directly tackled in any way. Similarly, Churchill et al. (Reference Churchill, Hunot, Corney, Knapp, McGuire, Tylee and Wessely2001), in the NHS R&D Health Technology Assessment systematic review of brief psychological treatments for depression, defined supportive therapy as ‘an inclusive term, often used in treatment outcome trials to describe an attention-placebo condition to provide a comparison to active manualized psychological interventions.’ Certainly, these interventions can result in symptomatic improvement, but there is no mystery as to why this should occur. Psychological interventions are susceptible to the so-called Hawthorne effect (e.g. Gillespie, Reference Gillespie1991), the tendency of people singled out for a study of any kind to improve their performance or behaviour simply because of the special attention they receive. (The name derives from an electricity plant in the USA where a famous series of studies established that just about any intervention significantly increased the workers' productivity.)

Should evidence from well-controlled studies outweigh evidence from poorly controlled ones? Until recently the answer to this question would have been emphatically yes; it is a familiar story in medicine for a treatment to show promise in one or more open studies, and then perhaps be successful in a crossover trial, only to go on to fail miserably in double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group trials. This simple algorithm has been complicated by meta-analysis, which typically includes all studies, good and poor, published and unpublished, in an effort to arrive at the best possible estimate of the size of the treatment effect. Use of such a broad-brush approach makes subsequent examination of study qualities desirable, even mandatory. Yet there seems to have been a reluctance to do this in the meta-analytical literature on CBT in major psychiatric illness. Even the otherwise exemplary Cochrane meta-analysis of schizophrenia (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Cormac, Silveira da Mota Neto and Campbell2004), which carried out separate analyses of CBT against TAU and supportive counselling, still failed to examine the moderating effect of blindness. The authors of meta-analyses of CBT for depression seem unperturbed by the fact that they are basing their conclusions on studies that have often been carried out against TAU or a waiting list control; that have not always been randomized; that sometimes failed to use diagnostic criteria; and that so far have ignored the moderating effect of blindness altogether. These issues are not trivial; the findings of our meta-analysis could be viewed as an object lesson on the importance of taking such sources of bias into account.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Centro de Investigación en Red de Salud Mental, CIBERSAM.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Note

Supplementary material accompanies this paper on the Journal's website (http://journals.cambridge.org/psm).

Appendix. Summary of included trials

Table A1. Treatment studies

CBT, Cognitive behavioural therapy; SST, social skills training; RDC, Research Diagnostic Criteria; Manchester, Manchester/Krawieka scale; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SAPS, Schedule for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; CPRS, Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PSYRATS, Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

a Used World Health Organization (WHO)-based criteria for non-affective functional psychosis.

b Patients also had a history of violent behaviour.

c Patient numbers at end of study approximate as exact data not given.

d Independent evaluations, but ‘it is likely that the patients made them aware of their treatment’.

e Patients met DSM-III-R criteria for major depression with atypical features (maintained reactivity of mood plus two or more of hyperphagia, hypersomnia, sensation of heaviness/leaden paralysis in limbs, lifetime sensitivity to rejection).

Table A2. Studies of relapse prevention

CBT, Cognitive behavioural therapy; TAU, treatment as usual; RDC, Research Diagnostic Criteria.

a Numbers refer to patients who showed full or partial recovery (see text).