1. Summary of paper and conclusions of the working party

This paper is the culmination of the work of the Risk and Customer outcomes working party, which was set up to consider whether customers adequately understand the risks and outcomes associated with life insurance products, how to avoid poor (or indeed maximise good) customer outcomes and finally to consider ongoing risk management through the product life cycles from a customer perspective. So far our work has focused mainly on future customers, although we briefly discussed current customers in section 5.3. Throughout the paper we focussed mainly on the United Kingdom, but have considered international inspirations where appropriate.

First, in section 2 we consider some of the previous industry failings ranging from endowments falling short of maturity expectations, personal pension mis-selling and more recently the well-publicised issues surrounding payment protection insurance (PPI). Such events have cost the financial services industry around £40 bn to correct over the last 20 years, driven through a number of factors including heavily sales-based cultures, inappropriate incentives and poor product design as well as regulatory failures along the way.

We then discuss in section 3 the current regulatory landscape across both the United Kingdom and other jurisdictions, concluding that whilst regulation has improved significantly during this period to reduce the risk of poor customer outcomes, gaps do still remain, particularly around the areas of disclosure, ongoing customer communications and how to take account of changing customers’ needs throughout product lifetimes.

In section 4 we explain that the customer outcomes are part of a complex and rapidly evolving framework with many stakeholders and covering the entire product lifetime and customer journey. This complexity could explain why gaps still remain in the current regulation and we propose to focus on a few critical aspects which are key to improving customers’ outcomes. These aspects are: disclosure to customers, needs-based selling (NBS) and ongoing assessment of outcomes.

The paper then considers in section 5 the crux of the issues in terms of how the current situation can be improved for customers in a cost effective manner. This takes the form of discussion around:

-

∙ Improved disclose of information to customers, not only at point of sale (POS) but throughout the product lifetime, including consideration to “stress testing” and illustrating the impact of extreme events.

-

∙ A focus on NBS whereby individual customer needs are better understood at outset, products are appropriately designed and have sufficient flexibility (e.g. through the use of optional rider benefits) to specifically meet these needs, allowing for the fact that these may change over time.

-

∙ The ongoing assessment and communication as a tool to ensure that a product continues to meet the customers stated needs and risk profile.

-

∙ Introducing duty of care as a means of enforcing financial services firms to encompass the best interests of their customers at the heart of the organisation through the power of legal enforcement – effectively ensuring customers are always treated fairly.

The implications of the above proposals to improve customer outcomes are then discussed in section 6. We first highlight that up-to-date, forward-looking illustrations and disclosure of worst case scenarios can help customers understand and select the most appropriate products given their circumstances, while at the same time may lead to the introduction of new product features. Second, we consider the impact of NBS on target market segmentation, product flexibility, distribution and remuneration. Third, we discuss who should bear responsibility for ongoing product assessment and how this can impact product design. Finally, we present the benefits of introducing a duty of care and its potential implications for firms and customers.

Finally we move on in section 6 to present our conclusions which are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Conclusions

We want to make it clear to readers that we do not have a “magic bullet” to solve all of the issues that we raise. This is an incredibly complex arena, with multiple stakeholders and a constantly changing regulatory landscape. We will not anchor our discussions and ideas in regulation, but have to bear in mind that the existing UK regulation and currently evolving European regulatory landscape (via Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) II, Packaged Retail and Insurance-based Investment Products (PRIIPs) and Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD)) will shape future developments.

Our key goal has been to demonstrate how customer understanding and outcomes could be improved if the ideas and conclusions of the research are followed. There are a number of areas where more research could be conducted – the issues around treatment of current customers, value for money (VfM) and the concept of duty of care. We look forward to continuing to make a contribution in areas such as these in the near future.

2. Background

2.1. Objectives of the working party and this paper

As the Risk and Customer outcomes working party, we were set up with the objectives of looking at:

-

∙ How can we help customers understand risks and outcomes for life insurance products;

-

∙ How to avoid poor customer outcomes or equally how to maximise good customer outcomes;

-

∙ And also to consider the management of risk from the customer’s perspective.

As a working party our key goal has been to demonstrate how customer outcomes could be improved if the ideas and conclusions of the research are followed. In this paper, we present our preliminary thoughts and recommendations and we would welcome your feedback and debate on this. Some of the recommendations will cost something to implement, and should therefore be supported by cost-benefit analyses that would weigh these costs against the potentially larger benefits to customers and the insurance industry.

2.2. Why this is still an important issue

To understand why the questions mentioned above are so important, it is worth highlighting the scale of the problems that we face. In the words of Winston Churchill, “those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it”. Even though we actuaries love the phrase “past performance is not an indicator of future returns”, it is worth spending a brief moment looking at some of the scandals which have plagued the financial services industry as some of these are very recent.

The endowment mortgage mis-selling scandal in the 1990s revolved around customers being led to believe that that payouts were guaranteed when they were not, partly due to high upfront charges and unrealistic return expectations, and leaving many policyholders with significant shortfalls. The estimated costs of the compensation paid to date are in the region of £3 bn (The Guardian, 2013).

Around the early 1990s, the industry was rocked by the pension scandal, where in 1986 (possibly ill thought out), social security reforms allowed public and private sector workers with (sound) organisational pensions to move to “non-club” personal pension schemes. The schemes were pitched to workers by commission based salesmen and in many cases, the workers would have been better off staying in their original scheme. The Financial Services Authority (FSA) has announced that the pensions mis-selling scandal will have cost insurers and financial advisers at least £11.8 bn in compensation payments (BBC, 2002).

And then we have the PPI scandal which is ongoing as we speak. In 2005 Citizens Advice labelled PPI a “protection racket”, claiming that PPI was expensive, designed to limit payouts to the genuinely ill and mis-sold to people such as the self-employed who would be unable to claim (Citizens Advice, 2005). The FSA began imposing fines for PPI mis-selling in 2006. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) monthly update shows on average a £300–£400 m per month payout for PPI compensation since 2011, with total payouts to February 2017 at £27 bn (FCA, 2016a).

Just to highlight again how important and relevant all of this is, a recent article in the Actuarial Post (2016) ranked the insurance sector bottom in providing the best customer experience, according to an annual Customer Experience Survey across 14 sectors.

So as an industry, we have experienced just how costly these scandals can be, in terms of both reputation and money, but the key question is (and this really is the key question): why do they keep happening?

2.3. Where did it all go wrong?

Martin Wheatley, former CEO of the FCA described this ongoing cycle of (mis)conduct as “a Mobius loop, where we appear to continually return to the same start point …” (FCA, 2015a).

Let us now look at some of the root causes, with a particular focus on the PPI scandal (please refer principally to: Parliament, 2013a, 2013b; Which, 2013):

A prevailing sales-based culture was often in place

-

∙ A sales-based culture manifests itself repeatedly as a contributor to many mis-selling scandals in Financial Services, for example, precipice bonds, endowment mortgages, ID insurance, inappropriate investments/funds, risky investment and PPI.

-

∙ This culture placed the achievement of sales targets over and above the long-term needs of each individual customer (FSA, 2012).

-

∙ Frontline staff were often under pressure to meet sales targets.

-

∙ And at least in some cases, salesforces were inadequately trained.

This is closely linked to remuneration policies for front-line staff:

-

∙ Inappropriate financial incentives for frontline staff played a role in virtually all mis-selling scandals in the financial services industry to date.

-

∙ In particular, bonus schemes for PPI meant that in some firms, advisers could receive six times as much bonus for selling a loan with PPI as for selling a loan without PPI.

Whilst front-line sales culture and remuneration were heavily skewed towards mis-selling, financial institutions also took on a tick box approach to compliance

-

∙ Historical record keeping standards have been poorer than required to enable accurate recreation of events that took place with the customer.

-

∙ Rather than asking whether a product or sales process provided fair treatment for the customer and best met their individual needs, some firms merely considered whether it complied with the detailed rules.

-

∙ This could be viewed as a double-edged sword whereby over emphasis on compliance forces firms to treat it as a tick box exercise to “jump through the hoops”.

Product design also contributed

Often, many of the products that have been associated with mis-selling have been fundamentally valid and important products for some customers, depending on their circumstances, eligibility and underlying appetite for risk.

-

∙ However, high product complexity and lack of transparency has meant that many consumers have had difficulty understanding the products and benefits that were sold (FSA, 2007).

-

∙ In many cases the features, benefits and qualifying criteria meant that they were not suitable to be sold to any consumers (Which, 2008).

In addition, misleading or poor-quality sales processes include

-

∙ Firms who automatically included PPI when consumers asked for a personal loan, not explaining that the insurance was not compulsory.

-

∙ They failed to explain the product conditions or its price to consumers and failed to ensure that each customer was eligible to receive the benefits (Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS), 2001).

-

∙ Also, some investment advisers recommended expensive and risky investment products without fully assessing a consumer’s attitude to risk.

-

∙ And some firms failed to adequately monitor the quality of their sales processes.

In some areas:

-

∙ There was a significant lack of effective competition around the purchase of ancillary products such as PPI and ID theft insurance.

-

∙ There was a lack of competitive pressure on price as it was difficult to shop around and the price of the product was also complex or not explicit.

-

∙ Instead of competing for consumers by designing better value and better-quality products, firms secured distribution by paying high levels of commission to providers for selling their products.

-

∙ In the case of PPI these commissions could reach over 87% of the product premium (Court of Appeal, 2011).

However, some firms ignored the warning signs of mis-selling from consumer groups and politicians

-

∙ Which? Conducted research and warned of PPI mis-selling in 1998, 2002, 2004, 2005 and 2007.

-

∙ Providers also failed to adequately learn from customer complaints and feedback.

-

∙ “If the industry had acted on these warnings, then mis-selling could have been prevented at a far earlier stage … Or, at least, the impact greatly reduced” (quoted in Which, 2013).

-

∙ However, in the early days compliance was a new management function that did not operate satisfactorily, while top management did not get involved as they should.

This was compounded by a weak regulatory approach where

-

∙ In the early days regulators did not adequately monitor compliance with the rules.

-

∙ The financial penalties imposed on providers for mis-selling PPI were initially a tiny proportion of the revenue gained from actively selling the products (FSA, 2008).

-

∙ This is changing whereby firms are now being heavily fined with criminal proceedings taking place against the individuals concerned.

Furthermore, some firms’ interpretation of the rules resulted in them rejecting legitimate complaints

-

∙ Even once problems of mis-selling were exposed, some providers spent several years rejecting complaints that the FCA and the FOS have subsequently disagreed with.

-

∙ This has resulted in further financial penalties and costs for some organisations as well as remedial activity to reopen previously closed complaints.

The FCA and the working party accept that it is unlikely that mis-selling could ever be eliminated completely. However, by creating the right incentives and culture in firms, and ensuring that the appropriate redress for consumers and regulatory penalties for poor conduct are put in place when it occurs, this should minimise mis-selling as far as possible (FCA, 2016b; see also Parliament, 1998, 2004).

3. Current regulatory landscape

Following on from section 2, we believe that mis-selling has ultimately occurred through a combination of:

-

∙ Firm behaviour

-

∙ Regulatory failure

-

∙ External market forces

So where are we today in respect of protecting end consumers from future mis-selling activity?

3.1. UK regulation

With the onset of recent mass mis-selling issues, the FCA has taken a number of actions to help reduce future issues, including:

-

∙ Enforcement action against firms and individuals has increased

-

- The FCA has significantly increased the average size of fines in recent years (from £1.2 to £8.5 m) as well as imposing a total of £298 m in fines for mis-selling between April 2013 and December 2015 (National Audit Office, 2016).

-

-

∙ Bonus adjustments have affected approach to remuneration

-

- The FCA’s Remuneration Codes sets out standards that certain firms must meet when setting pay and bonus awards for staff which now requires reductions in variable pay for senior staff in the event of misconduct (FCA, 2014a).

-

-

∙ Supervisory intervention has increased

-

- The FCA carries out many supervisory actions in relation to mis-selling, including meeting with employees of firms holding “significant influence functions”.

-

-

∙ Increasing competition between firms

-

- The FCA has an explicit objective to promote competition, delivered through initiatives to make it easier for consumers to switch providers. This is hoped to result in firms becoming more responsive to customer needs and less likely to promote sales driven cultures (FCA, 2013).

The FCA is also now taking a more active approach to identifying and responding to mis-selling risks, particularly for new products. Activities include:

-

-

∙ Widening the range of information sources which now include social media, consumer groups and mystery shopping exercises.

-

∙ Greater use of early intervention procedures. For example, in October 2014 the FCA used its powers to stop the sale of contingent convertible securities for retail customers, which is estimated to have prevented customer detriment in the range of £16–£235 m (FCA, 2014b).

-

∙ Identifying mis-selling risks raised by new market developments to enable earlier action. A good example here are the recent pensions reforms which the FCA believes could be a trigger for future mass mis-selling (FCA, 2015b).

-

∙ Introduction of the FCA mission which acknowledges the wide remit of the FCA and the finite nature of its resources. Within the 2016 consultation paper (FCA, 2016c), the FCA actively aims to target its activities to ensure the FCA’s strategic objective to protect consumers, protect the integrity of the financial markets and enhance competition is met.

The UK Government also announced in the Spring 2017 Budget plans (HM Treasury, 2017) to protect consumers from unnecessary costs and inefficiencies, which includes plans to make terms and conditions simpler and clearer (including in digital contracts). The exact details are not yet available but it is clear that even for simple products within the life insurance industry, terms and conditions run to several pages. This may well mean that it falls in scope for the government changes.

Whilst the above represents some of the changes from a regulatory perspective, this does not detract from the need for firms to be doing more to ensure that they only sell suitable products to their customers and ensure that customer needs are met by the products they provide.

3.2. Common themes of upcoming legislation in the European Union (EU)

Whilst the above relates to the United Kingdom, there are a number of themes emerging across wider regulatory initiatives within the EU. We have highlighted the most relevant ones emerging from IDD (EU, 2016), MiFID (EU, 2014a) and PRIIPs (EU, 2014b) below (please refer to Appendix 2 for further information):

-

∙ Aims to improve consumer protection in the insurance sector and harmonise the national rules.

-

∙ Coverage across the whole product lifecycle, including

-

- Product design

-

- Distribution

-

- Disclosure

-

- POS and ongoing assessment.

-

-

∙ Ongoing monitoring of firms’ behaviour around new product sales.

-

∙ Underlines the importance of target market and customer needs. Product features and distribution should be appropriate for the target market and remuneration should incentivise the distributor to act in the best customer interest and meet their needs.

-

∙ Aim to improve transparency with regards to fees and charges and distributor remuneration and to help the customer understand the product risks.

-

∙ Specific rules are left to the national authorities, so there is a certain degree of uncertainty with regards to the final rules, for example, disclosure of remuneration.

The changing regulation is an area which is still evolving and will have significant impact going forward.

3.3. Gaps in the current regulation

Most UK regulation is seen as focussing on the risks of mis-selling and conduct risk, as highlighted above, in particular through extensive POS disclosure.

It is clear that there is quite some variation in the methodologies used for life insurance illustrations in different markets. Most regulators require at least two scenarios, usually with prescribed projection rates. Please refer to Appendix 4 for further information. We believe that illustrations alone are not enough to ensure customer understanding of our products.

However, the provision of ongoing assessment has been less regulated to date, with a few notable exceptions. These include statutory money purchase illustrations for pensions and bonus notices for with-profits customers. The introduction of pension freedom has encouraged the FCA to add to its existing guidance on communications to flexi-access drawdown customers by emphasising the need for annual communications focussed on sustainability of income (FCA, 2015c).

From time to time, the regulator has provided some indications of their expectations in relation to post-sale communications. For example:

-

1) The FSA’s discussion paper on “Treating Customers Fairly after point of sale” (FSA, 2001) sets out the need for firms to take proper account of providing clear information to their customers after the POS as it plays an important role in helping to ensure that consumers are kept aware of product performance and in managing expectations.

-

2) In “Treating customers fairly – towards fair outcomes for consumers” (FSA, 2006), it was stated that “Post-sale disclosure plays an important role in helping to ensure that consumers are kept aware of product performance, their opportunities to act at certain points in the product lifecycle and changes in the terms and conditions”.

-

3) The FCA’s guidance document on “The Responsibilities of Providers and Distributors for the Fair Treatment of Customers”(FCA, 2016d) states that: “Firms should periodically review products whose performance may vary materially to check whether the product is continuing to meet the general needs of the target audience that it was designed for, or whether the product’s performance will be significantly different from what the provider originally expected and communicated to the distributor or customer at the time of the sale. If this occurs, the provider should consider what action to take, such as whether and how to inform the customer of this (to the extent the customer could not reasonably have been aware) and of their option to seek advice, and whether to cease selling the product”.

Consumers’ expectations are based on all the communications they receive. A lack of post-sale communication will result in their expectations being solely based on information provided before or at the POS. Where the industry does not communicate with customers thereafter, and take the opportunity to inform and, where necessary, modify expectations in line with how the contract is performing, it creates a risk of unfair outcomes and detriment for consumers and a reputational risk for itself.

In March 2016, the FCA published its thematic review on “Fair treatment of long-standing customers in the life insurance sector” (FCA, 2016e) and referenced the above documents, amongst others. The FCA is now consulting on additional non-handbook guidance in relation to ‘closed book’ customers. However, as it is likely that all customers will be closed book customers one day, the implications for the regulator’s expectations must almost certainly be seen more widely. In relation to post-sale activity, if the consultation is finalised as drafted, providers would be expected, amongst other things, to do the following:

-

1) Review products at least every 5 years to see if they continue to meet customers’ reasonable expectations.

-

2) Consider whether a product continues to provide a fair outcome to the customer, including assessing whether customers have received the investment return they could reasonably expect, or whether product charges consistently outweigh the performance being produced.

-

3) Provide at least annual communications to customers including, perhaps, details on the performance of the product, its value and the impact of fees and charges, for which more detail is provided on how this could be done.

-

4) Include a reminder of options, benefits and guarantees in the annual communication.

-

5) Consider carefully the layout and language used in both regular and event-driven communications.

It is apparent that, over the years, the regulator considers it has found clear gaps in the quantity and quality of ongoing communications to customers. However, we may need to wait some time to see if the latest guidance results in real changes in the quality of information and how, if at all, customers act upon the information provided.

As a working party, we have also discussed another emerging “gap” in the UK market, which may have resulted from the Retail Distribution Review (RDR) and the move to fee-based distribution, and that is the “advice gap” in the UK market. Please refer to Appendix 3 for further details.

The working party has investigated some potential solutions to this problem, which we discussed at the 2015 Life Conference. The working party and the majority of those that voted at the 2015 Life Conference agree that something should be done to close this gap, but that this should be based around sponsored advice or education rather than, for example, Government-approved products.

This “advice gap” is not the primary focus of our research, but is something that should be considered perhaps by another working party in the future.

3.4. Current disclosure methods for customer understanding of risks and outcomes

There are different disclosure and illustration requirements in different jurisdictions, which range from simple to more comprehensive. The working party believes that clear disclosure and benefit illustrations can definitely help customers understand risks and outcomes (FCA, 2016f). However, there are many aspects to consider and some of these are not straightforward. For example, increasing product complexity and lack of understanding of financial risks do not easily enable understanding. In addition, behavioural biases, difficulties in assessing risk and uncertainty over long term and in making trade-offs between present and future represent further obstacles that are not easy to overcome to ensure understanding.

The working party supports the concept of the Key Information Document (KID) required by PRIIPs from 2018, which in principle provides a good summary of key product information, risks, costs and potential outcomes in one document that should be less than three pages in length. Please refer the summary of upcoming European regulations and POS disclosure in Appendix 2 for more details.

4. Current framework

In the opinion of the working party, one of the reasons why gaps still remain in the current regulation is that the customers’ expectations and outcomes are part of a complex and rapidly changing framework with many stakeholders and covering all stages of a product lifecycle and customer journey. The working party discussed and analysed the various factors, stakeholders and processes that could make up this framework and how their interactions and relationships impact the customer outcomes.

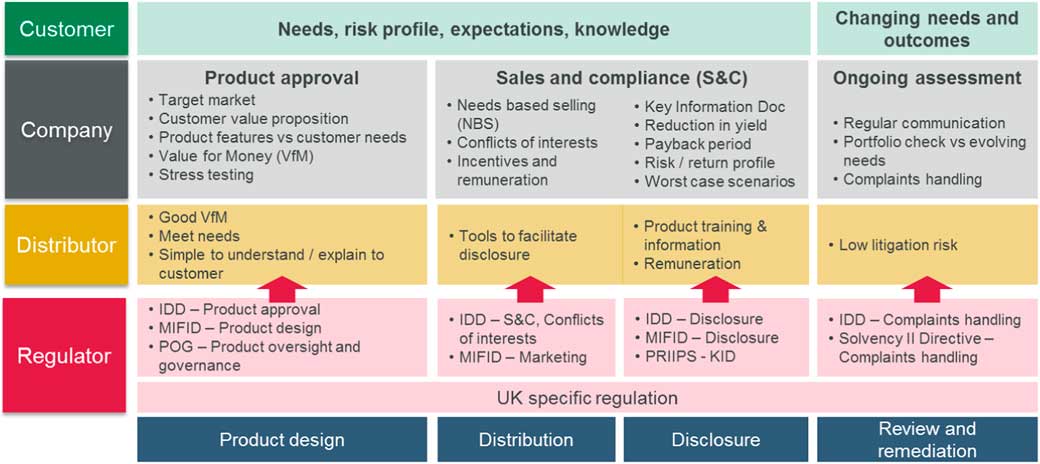

4.1. What this means for different stakeholders

The conclusions of our analysis of the current framework are summarised in Figure 1. For this paper we considered a simplified view with two dimensions – the stakeholders and the product lifecycle – together with the factors impacting each stakeholder at each stage of the lifecycle.

Figure 1 Framework with two dimensions: the stakeholders and the product lifecycle

4.1.1. Customer

To improve outcomes, all stakeholders would have to place the customers higher up on the agenda and at the centre of their actions and behaviours, business models and culture. More focus is needed on customer needs, their risk appetite, knowledge and expectations. These should be considered from the initial stage of product design to distribution to disclosure and over the whole customer journey since the customer needs will evolve/change and our products are expected to remain appropriate. Others have presented similar ideas in the past. Jeremy Goford, former president of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA), wrote a series of articles on “customer needs focus”, in the Actuary Magazine. In the first article (Goford, Reference Goford1996), Goford defined “customer needs focus” as starting with the customer’s needs, via the required benefits of the necessary products, in contrast to “customer focus” which started with the product offerings. In the second and third articles (Goford, Reference Goford1997a, Reference Goford1997b), Goford discussed how a customer’s needs could be analysed using a grid and met by matching benefits to needs.

4.1.2. Company

On the insurance firm side, what is important is to create a comprehensive framework that brings the customer view into the product development and the sales and compliance guidelines. Firms need to move away from the traditional model of product development which starts from the benefits we know and like to offer to a new approach where we develop the benefits aimed at meeting identified customer needs.

A key element is aligning the business strategy and company culture as well as the governance to the aim of ensuring good customer outcomes. A defensive attitude aimed at avoiding regulatory intervention is not sufficient. And a customer centric approach that constantly deliver good outcomes can in the long-term drive revenue and profitability growth.

4.1.3. Distributor

The distributor plays a very important role as well. To be able to meet the customer needs, they need products which offer good VfM, are simple and easy to explain.

In the sales process, the distributor needs to help the customer understand the product and the risk, so illustration and presentational tools are important.

The distributor needs to be trained to discover the customer needs and match them to appropriate product features, so a needs-based sales approach and good understanding of product features are key.

The distributor is often exposed to litigation risk and will want to minimise this, which of course can be achieved if product outcomes meet the customer expectations over the product life time.

4.1.4. Regulator

The regulator tried to cover and influence all these areas and stakeholders, from product design and development, to sales and distribution, to disclosure. The regulatory environment is still evolving, and this needs to be borne in mind as we progress.

From this framework we investigated a few critical aspects that are key to helping customers understand risks and outcomes for insurance products, avoid poor outcomes and also consider the ongoing management of risk from the customer’s perspective. These aspects are: disclosure to customers; NBS; and ongoing assessment and review of outcomes. We will discuss these aspects in more detail in sections 5 and 6.

5. How we propose to improve customer outcome

The United Kingdom has the largest insurance and long-term savings industry in Europe and the third largest in the world after the United States and Japan (Association of British Insurers, 2015). So we will use the United Kingdom as a demonstrable example to explore possible solutions to help customers to understand risks and outcomes of insurance products. We will present our ideas on improving customer understanding and outcomes through clearer disclosure, a needs-based sales process, ongoing assessment and even through an overarching duty of care.

5.1. Comparing risk/return profiles of different insurance products

Currently in many illustration systems the illustration rates are locked-in at the POS and they may not be appropriate later in the policy term. The customers’ expectations would then be anchored to the POS illustrated benefits which may become unsustainable if the economic environment had changed later on. An example is the case of mortgage endowments where the bonus rates had to be cut over time due to the falling yields and the projected maturity values could not be achieved. This problem strengthens the case for regular reviews of the projected benefits for the in-force book and clear communication to the customers if the economic and market conditions changed.

For example, in the United Kingdom, benefits are shown under three different nominal rates in the illustration – see Table 2 (FCA, 2016g).

Table 2 Illustration Rates in the United Kingdom

In the working party’s opinion these rates seem quite high in light of the current low interest rate environment, particularly the lower rate.

The working party believes that illustrations on a range of expected returns on the assets in which the customer’s funds will be invested, and a brief explanation of the main assumptions on which the illustration is based can help customers compare the risk/return trade-offs for different products. In order to manage customers’ expectations, the range of expected returns should capture negative as well as positive scenarios, and ideally should reflect the volatility of returns from different asset classes. Methodology for setting illustration scenarios should be forward looking, regularly reviewed and updated to avoid creating unreasonable customers’ expectations and to manage these expectations over the policy lifetime. Our view is supported by EIOPA in the upcoming PRIIPs regulation.Footnote 1

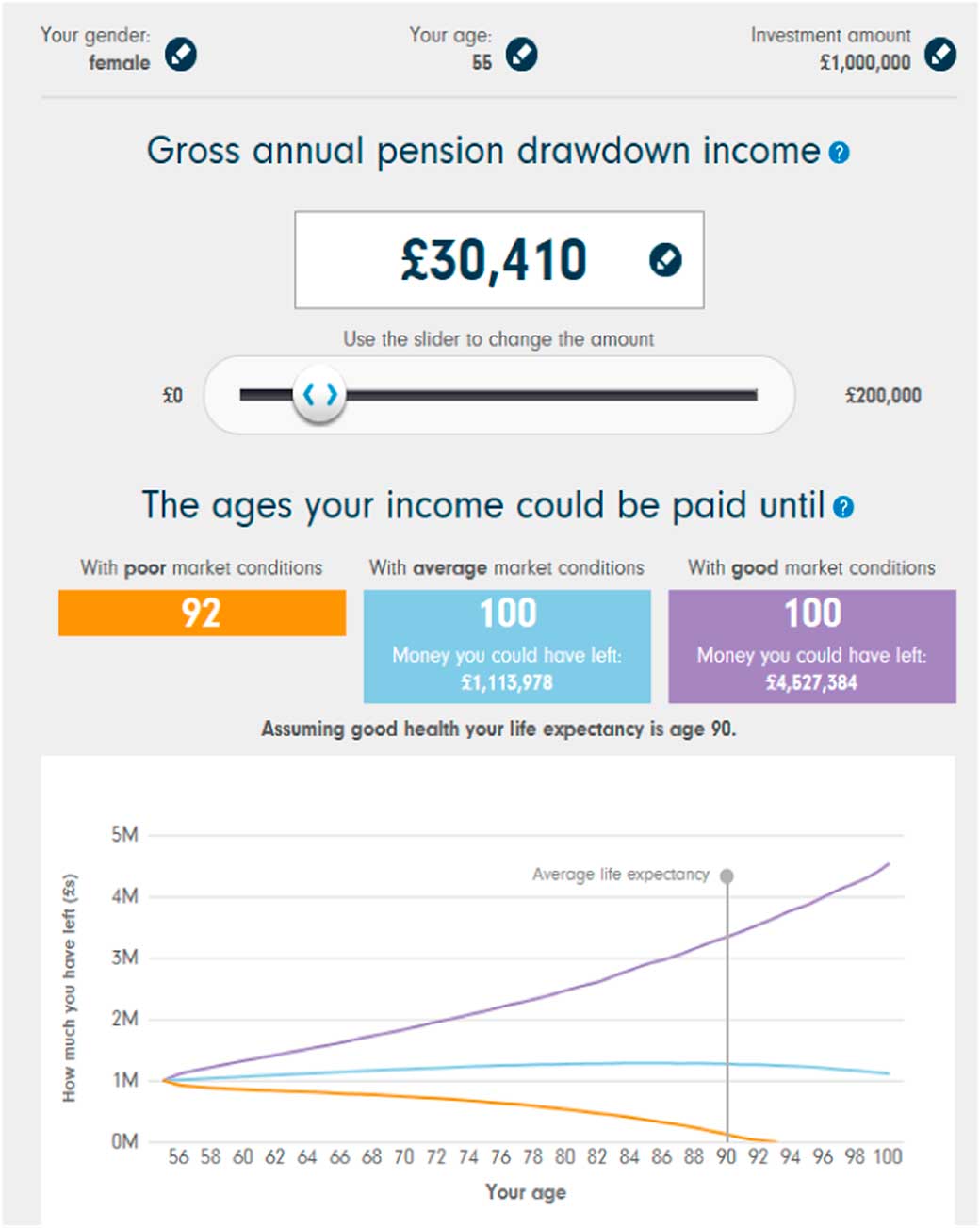

5.2. Online illustration system allowing input of customers’ own scenarios

Given the complexity of risk/return profiles of different products and heterogeneity of customers’ circumstance and risk appetite, relatively sophisticated judgements are often involved in buying an insurance product. Developing online illustration tools that allow customers to explore application scenarios, possibly including some own scenarios, on their own at any time can help ensure that customers know what they are buying and thus avoid mis-selling. Below are some existing examples:

-

1. One of the most meaningful existing online illustration tools (to date) perhaps is the one provided by Fidelity International.Footnote 2 It allows customers to see different options with different market conditions instantly (see the following screenshot for an illustration):

-

2. Liverpool Victoria (LV) offers a range of online tools for retirement planning, pensions and annuities.Footnote 3 The following screenshot shows an example of an Annuity Comparison Tool provided by LV:

-

3. Scottish Widows has also introduced some online tools but they involve many questionnaires, which customers may try to avoid.Footnote 4

5.3. NBS

5.3.1. Introduction

The next point we want to discuss in more detail is NBS. This was related to the working party’s objective of avoiding poor customer outcomes relative to expectations and investment objectives. We can say that NBS has two sides: “value” needs and “risk” needs.

5.3.2. Understanding customers’ value needs

Regarding the consideration of customers’ value needs in product design we want to stress three aspects.

First, we need to consider VfM, that is, what the customer gets in return for the premiums paid both before and after tax. There are various way one can do this: (a) calculate the customer internal rate of return at different durations; (b) determine the customer payback period; (c) reduction in yield (RiY) method. These are suitable mostly for savings products and it gets more difficult when it comes down to protection. For protection, the benefit types can vary significantly between different propositions. The ratio of present value of expected benefits to present value of premiums can be used as a VfM proxy. For Life Insurance products, an industry wide VfM methodology and key performance indicators are still missing thoughFootnote 5 .

Second, when designing products we should start from the needs of the target market and understand how the product has to be structured to meet those needs. The traditional market segmentation by risk should be supplemented by a “needs” segmentation (Money Advice Service, 2017a). For an example, see Table 3. It lists the key needs and for each identifies the product features that are appropriate for meeting that need. And a list of features which are forbidden can also be added, which is also recommended in the IDD.

Table 3 Key Needs and Product Features that Meet those Needs

Third, product stress tests should be carried out to understand not only the risks for the company, but also the situations when the product fails to meet the needs of the target market and its circumstances. For example, for mortgage endowments, such a situation is when the bonus rate falls below the level needed to ensure that the maturity value is sufficient to repay the loan, which is the customer need the product was designed to meet.

On all of these three aspects we feel that more can be done by firms and that would have a significant positive impact on outcomes.

On the distribution side, as proposed by the IDD, the remuneration should be aligned with NBS to encourage the distributor to act in the customers’ best interests – discover their needs and match them with appropriate products. Remuneration schemes should also not promote any conflicts of interest in the sales process, and ideally the level of remuneration should reflect the qualification of the intermediary and their work done.

Adequate training, information and tools should be provided to ensure the distributor go through the needs discovering process and has a procedure for matching needs and product features.

5.3.3. Understanding customers’ risk needs

The “risk” need is the second aspect of NBS. The key here is that the customer risk profile or appetite should match the product risk.

On the product side, the risks of poor outcomes for the customer can arise for various reasons (Association of British Insurers, 2013):

-

∙ Product’s risk/return profile was not properly presented and understood by the customer giving rise wrong/unreasonable expectations.

-

∙ Performance was worse than expected at POS and the customer was not warned about the potential downside

-

∙ The product was not sold to the target market it was designed for and the customer cannot access the benefits when needed.

-

∙ The customer’s circumstances have changed after conclusion of the sale.

On the customer side, the risk profile is determined by a wide range of factors: net worth and risk-bearing capacity, investment horizon, other assets and liabilities and how these are correlated among them and with the markets, protection from other sources, for example, state safety net.

Understanding the customer risk profile is key for making the correct product recommendation, but matching the two sides is not straightforward: we need a proper assessment process, a methodology for matching and the ability to maintain the match over the customer journey. The working party has investigated some potential methods for matching the customer risk profile with the appropriate products, and discussed these at the 2015 Life Conference. The working party and the majority of those that voted at the 2015 Life Conference supported informed free choice: the customer should be provided information on products best matching their risk profile, but ultimately should be free to choose alternative products if they want.

5.4. Ongoing assessment from customer’s perspective

The ongoing assessment that a product is suitable for the customer needs and risk profile is one area where we feel that firms should do more and is also one of the most difficult parts.

Most insurance products are long term and in general not flexible enough to keep up with the rapidly changing needs (e.g. change in health, wealth, social, family situation). Their performance is affected by external and often unpredictable factors – volatility of financial markets, regulatory changes, technology, etc.

This should be kept in mind already in the product design stage: if we stress test the product and investigate worse case scenarios from the customer perspective we will be able to identify situations when the product fails to meet the target market needs and we will be prepared to act in those situations. Note that from a customer perspective, the stresses need to consider a wider range of factors affecting the customer circumstances, for example, while for a firm perspective the stress is only 25% fall in equity values, for the customer this can be associated with a strong economic downturn and the higher risk of redundancy.

Product performance should be monitored against the initial illustration and the worst case scenarios identified.

Regular communications with customers is key. These should cover not only financial information and projections, but also a reminder of what need the product was intended to meet.

Finally firms can extract valuable information from data analysis, for example, complaints and claims data or customer surveys.

A more complicated aspect could be to ensure that the product is sold to the target market it was designed for. Sales data analysis can provide some insight and the target market should be defined so that monitoring is subsequently possible as part of the regular management information reported in the firm.

5.5. Introducing a duty of care on firms

Another approach is to adopt a duty of care, either through regulation (as proposed by Financial Services Consumer Panel (FSCP), 2017) where the Financial Services Markets Act would be amended to include explicitly the expectations of the regulator on the relationship between firms and their customers.

The FSCP have highlighted a disconnect between the ideology behind the current Treating Customers Fairly (TCF) obligations and the firm taking responsibility for the decisions it makes. The TCF principles do not fully remove a conflict of interest between the firm and the customer which does not entirely deter firms from mis-selling products and services.

The idea is that financial products are inherently complicated and require equally complicated rules to regulate them and to bridge the information asymmetries which exist within the financial services industry. However, the complicated rules allow firms the opportunity to side-step obligations rather than face them head-on. Introducing a duty of care would add a safety net to prevent getting around the rules that are there to protect customers. It may also lead to a reduction in overall regulation as the requirement to act in the customer’s best interests is enshrined within law and the regulations designed to encourage that behaviour are no longer required. Instead, a more principle-based approach would lead to the correct behaviours which ultimately ensures customers are treated fairly and have a product which meets their needs.

This topic is a current area of debate within the UK industry, and with regulation as a whole generally moving towards greater transparency and more information for customers, the balance between meeting customers’ needs and regulation is one debate that will likely keep going.

However the industry chooses to proceed, it is clear that ensuring the needs of customers are met and being able to demonstrate this is a greater area of focus within regulation.

5.6. International examples

The problem of life products’ outcomes not meeting customers’ expectations has not been limited to the UK market. Other markets facing this issue have adopted alternative or similar measures aimed at improving transparency and disclosure, promoting NBS and avoiding mis-selling and conflict of interest. These measures can provide additional inspiration for potential solutions to improve customers’ outcomes and we highlight below some interesting examples from the markets we have researched:

-

∙ Some Governments sponsor free guidance services to help customers choose appropriate insurance and investment products. These include the United Kingdom’s Money Advice Service (2017b) and Pensions Advisory Services (HM Treasury, 2015, 2016; Cheong, Reference Cheong2016), and Australia’s Money Smart (2017) and Superannuation (2017) services.

-

∙ In Taiwan, guided product selection is a very common approach, where the selling process is regulated to ensure appropriate matching between the product risk and the customer needs and risk profile. The approach works by first assessing all products and giving each a risk rating using standard methodology that would be defined for use across the whole industry. Potential customers must then complete a “Know Your Customer” questionnaire to determine their individual risk rating, and then only products with the same or lower risk grade can be offered by the distributor.Footnote 6

-

∙ The United Kingdom and the Netherlands have a “no commission” structure, which can be complemented with automated or simpler methods. In addition, drawdown products offer retirees choice and flexibility in retirement, where the income they take can be varied over time and not all of their retirement savings need to be moved into the post-retirement pot in one go.

-

∙ In the United States, brokers are obliged to carry out frequent assessments of products and suitability for their clients (see Securities Exchange Commission, Reference Schoeff2008).

-

∙ In Asia, the approach to ensure flexibility over the contract term is to have a generic savings type product. Customers then choose risk riders to attach to this savings product which will meet the needs of the customer at that particular time. Then over the lifetime of the product, the riders can be changed to meet the changing needs of the customer.

-

∙ In Brazil, providers offer products which can change as your household income changes, so, for example, one can insure parts of the car in line with one’s income.

-

∙ In South Africa, HIV-related products were priced on a forward-looking basis and working towards keeping customers healthy in the future rather than based on historical behaviour to date, which is how other products are priced. Some insurers then monitor customers’ adherence to medical treatment through links with healthcare providers and text message reminders to policyholders when appointments are due and warnings if appointments are missed. Insurers are providing life insurance cover to those affected which then allows people to secure home loans and start businesses, but also provide a crucial form of security for dependents. With this forward-looking approach, some insurers in South Africa have seen that customers actually get 15% healthier after 6 months (see AllLife, 2016).

-

∙ In the Netherlands, the Dutch Government introduced an Amendment Act Financial Markets 2016 which introduced a duty of care on financial services providers. This made it a legal obligation for firms to ensure they act in the best interests of their customers (Overheid, 2017).

-

∙ The US Department of Labour are introducing a Fiduciary Rule such that advisors must act in the best interests of their clients, and to put their clients’ interests above their own. Advisors must not conceal any potential conflict of interest, and all fees and commissions must be clearly disclosed. The definition has been expanded to include any professional making a recommendation or solicitation, and not simply giving ongoing advice (see Department of Labor, 2016).

6. Implications and benefits of our proposals

In this section, we consider the proposals of section 5 and show how each of them can contribute to achieve the key objective we set at the beginning of this paper: help customers understand risks and outcomes for life insurance products, avoid poor customer outcomes and improve the management of risk from the customer’s perspective.

6.1. Improving customer understanding

The working party believes that up-to-date, clear and understandable disclosure will improve the customer’s ability to select the most appropriate life insurance product for the customer’s needs and improve the customer’s understanding of the basic features of the product that has been purchased or is under consideration. And there is scope to improve this further, as proposed under PRIIPs. Illustrations can be used to define and show the worst case scenarios as well as take our customers through a journey to explain what could go wrong or provide them with an idea of what circumstances the particular product would not be good for them.

More transparency about worst case outcomes may lead to the introduction of additional product features designed with the aim of mitigating large negative outcomes by, for example, using out of the money options. However, the downside of creating such products is that it introduces an additional cost, which may or may not make the product attractive. The aim of this is to help customers understand the products and the risks better.

This approach does raise the question of whether customers should be enabled to choose scenarios or provide input to the process. It is less clear cut what the process could be or how the scenarios should be, particularly the worst case scenario, without knowing the individual needs and requirements. However, by setting out more information you’re empowering the customer to make a more informed decision with the freedom to choose whichever product they wish.

6.2. Advantages of NBS

NBS is a way of avoiding poor customer outcomes. This may mean that a more granular market may arise which caters for niche groups (e.g. impaired lives), or that providers will become more selective over the products they offer or only offer more generic products, or providers will unbundle products to match individual specific needs. This is likely to increase innovation in the market.

In practice, the product features and flexibility will determine whether the needs can be met. Complex needs often require more complicated solutions yet products need to be flexible to meet the evolving needs of the market. Thinking about what needs the product should meet, how flexible the product should be to meet future demands and what are the costs and benefits (from the customer and firm perspectives) of different options should all be at the top of any product development and sales capture.

In addition, the way products are sold will need to be aligned with meeting the needs of customers. We would want to ensure distributors actively identify and adequately match customer needs. Would a model like that in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands of no commission be enough to ensure this?

The working party believes that remuneration based solely on sales volume will be replaced by incentives linked to customer service quality and ensuring the needs are met. For example, EIOPA have flagged volume-based remuneration schemes as potentially leading to conflicts of interest in the sales process (EIOPA, 2017).

In addition, this will have an impact on the manufacturer – to what extent does the manufacturer have to ensure that the distributor follows the NBS approach? Manufacturers will have to be more proactive in monitoring and controlling distributors and in collecting and reporting the necessary data in the management information systems to ensure such an approach is feasible.

Moving on to optimal product choice, what are the implications of moving to a needs-based approach in a competitive market place where everyone wants to sell and make money? Do providers have a duty to inform/raise awareness that other products are better match for the particular need (e.g. when the company does not offer impaired annuities, although these are available from other providers, which would be a better option for a customer in poor health). While this is unusual outside financial services, we need to remember that some insurance and pension products are very difficult to compare and understand, involve long-term commitments from both the provider and the customer and wrong choices can have dramatic consequences for the policyholders.

We also believe that at some point the customer has to take responsibility for ensuring the product is understood and suitable. Education is key! The knowledge required needs to be built up from a young age so that the population is financially literate and more aware of the products and risks they are taking. This is a long-term goal but something that is extremely important in balancing the knowledge gap between customers and providers.

6.3. Benefits of ongoing assessments and communication with customers

Ongoing assessments are a key part of the thinking we have done. We believe that one-off irreversible decisions to buy a product should be avoided, rather products should continually meet the needs of the customer and those needs should be reviewed on a timely basis to ensure the product remains suitable.

The responsibility for a regular review and suitability assessment can fall to the company/distributor or the customer. In the United States, brokers are required to check annually the product suitability for variable annuities; they are also required to update client risk profiles, investment objectives and review existing investments against the updated client objectives. The responsibility very much lies with the broker to ensure the products remain suitable for the customer. This could be one way of bringing in an ongoing assessment.

Alternatively, the responsibility of providing regular information about the change in circumstances could fall to the customer. We want to encourage customers to regularly inform the insurers about their evolving needs, for example, include on the anniversary letter statements such as “if your personal/family/health/working/income/wealth status has change significantly, please contact …”. The customer may not be financially literate enough to say whether the product is still suitable, therefore the insurers should be responsible for assessing if the product they sold is still suitable to meet the needs and informing the customer accordingly. An in-depth regular assessment can be offered as a service in return for a fee, similar to the initial advice at the POS. This can also open the option for the customer to choose between a simple standardised product with no regular reviews (but most likely for shorter term) and a more flexible, complex, longer term, lifecycle-type product.

The working parties and the majority of those that voted at the 2015 Life Conference was for a shared burden between the company and the customer, for example, annual touchpoint with the customer encouraged to contact the company if their circumstances have changed.

Products could be set up in a very flexible way, for example, a single product over a customer’s lifetime that could be changed at will by the customer to meet their evolving needs. For example, various rider options could be attached to provide the benefits required by the policyholder, all within a single product. The other end of the spectrum is to have short-term products with mandatory renewal from the customer’s side. This could be a move away from products like Whole of Life and a step towards term assurance products where at the end of the term, the policyholder would need to assess for themselves whether the chosen level of life cover is adequate for their current needs.

It is important to note that the proposed flexibility of products and regular reviews will have a cost. We will need to consider whether customers are prepared to pay for such a service.

Whichever option is chosen, there needs to be a link back to the product development stage. It is important to know that if the target market, needs and value proposition were not clearly defined in the product development stage, then it will be difficult to monitor good outcomes effectively.

Customers should also be encouraged to shop around and regularly investigate and assess if switching their products is appropriate. However, this will have an impact on profitability of providers, but equally that should encourage innovation in the market to retain customers.

6.4. Introducing a duty of care on firms

A duty of care is designed to ensure that the firm acts with the best interests of customers. As discussed above, the current UK industry debate centres on whether the TCF obligations go far enough to ensure customers interests are appropriately considered.

There are advantages as well as disadvantages to the introduction of a duty of care. On the one hand, introducing a legal duty of care may appear more onerous but may in fact actually reduce legislation. If the culture is adequately set up to ensure the duty of care is driven throughout the firm, this will ultimately lead to a reduction in the onerous amounts of compliance already in existence within firms. On the one hand, a legal obligation on firms may discourage innovation and reduce the complexity of products. However, we believe it may also open up opportunities for firms to innovate and compete without the unnecessary red tape currently required by compliance with a number of rules all intended to achieve the single purpose of fair treatment of customers.

However, enshrining the requirements into law will does open up firms to possible legal action. It is noted that the intention of the FSCP in proposing this is not that consumers should be able to take legal action, but rather that this would work as a preventative measure and disputes would continue to be resolved by the FOS. So while there may be a reduction in regulation a firm must comply with, the risk of legal action may be enough to suppress innovation and possibly the breadth of offerings within the market. This in turn would be bad for the customer and limit competition which in turn affects price. This would also have knock on effects for the industry and the Government through increases in the protection and savings gap, which may ultimately need to be filled through Government resources for example, long-term care needs through adult social services care schemes.

A duty of care ensures the aims of existing regulation such as TCF and upcoming regulation such as IDD will meet the aims of improving fair customer outcomes. In that respect, the ideas behind the duty of care are not new and should not shift the culture away from the customer centricity we already see within the United Kingdom. This may be an exciting opportunity to ensure that all those within the financial services, regardless of type or firm for example, insurer or bancassurer and regardless of position adhere to the aim of ensuring the customer is at the heart of what we do.

The idea here is that a duty of care introduces an element of trust within the relationship between a firm and its customers. That trust is demonstrated by the firm having a legal obligation to ensure as a firm they work towards reducing the information asymmetries that naturally exist within the financial services industry and allow customers to take on responsibility for the choices they make.

Duty of care obligations would also introduce a level of trustworthiness in the market. As trust is a function of how the market regards the particular profession or industry, this can only lead to greater confidence and opportunities for sales and product development. What the industry as a whole is missing is a means of demonstrating that it is working with the right intentions, particularly in light of the numerous mis-selling scandals over previous decades.

An alternative to introducing a legal duty of care is to extend The Actuaries Code to drive behaviour within the profession. However, this will only be of limited use but it will be a unique opportunity for the IFoA to take a market leading position and encourage the behaviours that should be expected already of firms.

As a working party, we are open to the idea of introducing a duty of care and welcome further debate on this. One area for discussion is the relation of the duty of care of the firm to the duty of care for particular individuals, including the intermediary. A duty of care should clearly articulate the requirements on a firm to demonstrate they are working in the best interests of their customers. That will in turn ensure that the needs of those customers are met. The approaches described above such as NBS and ongoing assessment may be viewed as best practices for firms seeking to demonstrate some compliance with the duty of care.

7. Conclusions and recommendations

This section summarises our main conclusions and recommendations. An overview is provided in Table 4 and some of the key recommendation related to disclosure, NBS , ongoing assessment and duty of care are briefly discussed below.

Table 4 Conclusions

The consideration of risk and customer outcomes is part of a complex landscape with competing interests, functions and stakeholders. We need to consider all stakeholders and be prepared to adapt to an intricate and rapidly changing regulatory landscape. Regulators are taking increasing interest in these topics, but we should not overburden our business and customers with boilerplate disclosures and we have to recognise potential unintended consequences of regulation. One example of this is different product offerings for mass and HNWI in the UK market and a potential gap in the market for the middle ground, which is not served by advice.

Despite this, improved and more dynamic disclosure can be beneficial to help customers understand the risks and outcomes for insurance products. Product risk rating and a better match to the customer’s risk profile can help manage expectations and improve outcomes. It is important that customers understand “what could go wrong” in the future.

NBS has been much discussed in the past, for example, Jeremy Goford’s exhortations from 20 years ago to do better. It is not clear that this was successful. We need to reconsider the way we design products and propositions, by starting from the target market and customer needs. Additionally, in order to avoid conflicts of interest in the sales process, the working party believes that remuneration based solely on sales volume will be replaced by incentives linked to customer service quality and ensuring the needs are met.

We support an ongoing assessment of products and needs to try to ensure that they are still suitable. We should avoid as much as possible one-off irreversible decisions and increase the number of touch points with customers to ensure that products remain appropriate. The touch points exist in many cases and could be adapted to improve this very important, and possible neglected, part of the product lifetime.

The ongoing industry debates around a duty of care for the financial services sector are a welcome step towards ensuring the needs of customers are met. There are advantages and disadvantages to setting out a requirement on firm to ensure they operate with the best interests of their customers which is in line with the intentions behind TCF. It is unclear whether this will materialise but what is certain is that the regulator is making a greater emphasis on firms to demonstrate fair customer outcomes either through disclosure of further information through incoming regulation such as PRIIPs and IID.

There is no way for the industry to avoid moving forward towards improving customers’ experience of our life insurance products, and this change should be welcomed and actively embraced. The working party hope that the ideas presented in this paper will help firms to take that leap forward.

Acknowledgements

The working party would like to thank the referees for their useful comments and suggestions, which have helped to improve the paper. Particular thanks is given to the Life Research Committee for their input and to Chris O’Brien personally for his detailed feedback on the paper. Helpful comments received from the Life Conference in 2015 are greatly acknowledged. The authors would also like to thank the IFoA’s library for providing us the articles by Jeremy Goford published in the Actuary magazine. Useful comments and inputs from Teresa Fritz and Mark Chidley from the FSCP are also greatly acknowledged.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of invited contributors and not necessarily those of their employers or the IFoA. The IFoA do not endorse any of the views stated, nor any claims or representations made in this (publication/presentation) and accept no responsibility or liability to any person for loss or damage suffered as a consequence of their placing reliance upon any view, claim or representation made in this (publication/presentation). The information and expressions of opinion contained in this publication are not intended to be a comprehensive study, nor to provide actuarial advice or advice of any nature and should not be treated as a substitute for specific advice concerning individual situations. On no account may any part of this publication be reproduced without the written permission of the IFoA.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Results from a survey carried out at the Life Conference 2015

As part of the working party’s research, a survey was conducted during our presentation at the 2015 Life Conference in Dublin. The questions and responses are summarised in Table A1. Around 25 participants voted and respondents tended to agree with each other.

Table A1 Results from a Survey Carried Out at the 2015 Life Conference

Most of the respondents supported informed customer choice rather than heavy-handed approaches, such as legislation, to the issues raised. The one outlier concerned risk rating for our insurance products, where the majority of respondents supported a regulatory-defined methodology with input from the actuarial profession. Interestingly, this is actually very close to the methodology for product risk rating proposed by the PRIIPs regulation.

Appendix 2: Further material on upcoming European regulations

IDD

-

∙ It is a revision of the Insurance Mediation Directive (IMD) (Directive 2002/92/EC).

-

∙ Key objectives are improving consumer protection in the insurance sector and harmonise the national rules.

-

∙ Covers all sales of insurance products, whether by insurance intermediaries or insurance firms.

-

∙ Introduces two general principles

-

- insurance distributors must “always act honestly, fairly and professionally in accordance with the best interests of customers”;

-

- and that all information must be “fair, clear and not misleading”.

These two principles are more or less the same as in the FCA’s existing Principles for Business.

-

-

∙ Initially it required the disclosure of distributor remuneration. In the final text, this requirement was relaxed and replace by a disclosure of the

-

- nature of remuneration

-

- basis of the remuneration – that is, whether it is in the form of a fee paid by the customer, a commission or other economic benefit. Where the fee is payable directly by the customer, intermediaries must disclose the amount of the fee or, where this is not possible, the method for calculating it.

-

-

∙ Member States will have to lay down rules ensuring remuneration systems do not conflict with the distributor’s duty to act in the best interest of its customers. In particular, remuneration systems should not encourage distributors to recommend a particular product when a different product could be offered that would better meet the customer’s needs.

-

∙ Requires the product approval process to specify a target market for each product. Need to ensure that the distribution strategy is consistent with the identified target market.

-

∙ For investment-based products, fees, charges and the cost of advice must be disclosed to the customer.

-

∙ Member States are allowed to prohibit or further restrict the offer or acceptance of fees, commissions or non-monetary benefits from third parties in relation to the provision of insurance advice.

-

∙ Intermediaries and firms are required to obtain the necessary information regarding the customer’s knowledge and experience in the investment field their financial situation, ability to bear losses, investment objectives, risk tolerance. This information should be used to recommend products that are suitable for the customer and, in particular, are in accordance with his risk tolerance and ability to bear losses.

Product oversight and governance (POG)

-

∙ This is a key component of the IDD aiming at minimising potential consumer detriment. The Guidelines contain 12 principles for improving the POG. Key recommendations are:

-

- The firms should only design and bring to the market products that meet the needs of the identified target market.

-

- The firms test and assess whether the products remain appropriate under a range of scenarios, including stressed scenarios.

-

- Need to monitor on an ongoing basis that the product continues to meet the needs of the target market.

-

- The firm should select distribution channels that are appropriate for the target market. Verify that distribution channels act in compliance with the manufacturer’s POG arrangements.

-

MiFID II

-

∙ The goals are increased transparency within financial markets and to create a level playing field between trading venues.

-

∙ MiFID II is aiming to address the shortcomings of the original MiFID release and respond to lessons learned during the financial crisis.

-

∙ It made amendments to IMD1. The requirements are in line with the final proposal for IDD as outlined before.

-

∙ The design, marketing and distribution of products must be tailored to the target market.

-

∙ Remuneration and sales targets should not incentivise staff to recommend inappropriate financial instruments to retail clients.

-

∙ Provision of information regarding costs, charges and the cost of advice.

-

∙ Firms must also indicate whether they will provide the client with a periodic assessment of the suitability of recommended financial instruments.

-

∙ Firms must tell clients in advance if investment advice is given on an independent basis and whether it is based on a broad or more restricted analysis of the market and, in particular, whether the range is limited to financial instruments issued or provided by related entities.

-

∙ Firms that provide advice on an independent basis must assess a sufficiently large number and diversity of financial instruments available on the market and should not limit the range to instruments issued by the firm or related entities.

-

∙ Financial instruments should be regularly reviewed to assess whether the product and distribution strategy remain appropriate for the target market.

-

∙ New products must specify the target market and ensure that risks to the target market have been identified and that the distribution strategy is consistent with the target market.

PRIIPs

On 15 April 2014, the EU parliament formally adopted the proposed regulation on KID for PRIIPs (EIOPA, 2016). Manufacturers of PRIIPs will need to provide standard KIDs containing a summary of information on the investment products while advising or selling their products to retail investors.

The KID represents a significant challenge for both product manufacturers and distributors, including banks, investment firms, insurance undertakings and asset managers.

Regulation is expected to come into force on 1 January 2018.

The aim is to improve transparency in the investment market for retail investors. The proposal aims to ensure that retail investors are able to understand the key features and risks of retail investment products, whilst ensuring a level playing field between different investment product manufacturers and those selling their products.

-

∙ Under the new PRIIPs Regulation, a product manufacturer must publish a KID on its website before a packaged product or insurance-based investment product is made available to retail investors.

-

∙ The KID will be a standardised document of up to a maximum of three pages of A4-sized paper. This will allow consumers to compare different PRIIPs.

-

∙ The person advising or selling the packaged or insurance-based product will be required to provide the KID to retail investors before he makes an offer to sell or sells the product.

-

∙ KIDs are designed to help consumers to understand PRIIPs, estimate the total cost of their investment and make them aware of the risk-reward profile.

The KID must contain the following information:

-

∙ A description of the product, its objectives and a description of the type of retail investor to whom the PRIIP is intended to be marketed, in particular in terms of the ability to bear investment loss and the investment horizon.

-

∙ A section on the risks and return to the customer. Should contain:

-

- A summary risk indicator

-

- Narrative explanation of the risk

-

- Indicate the maximum possible loss of capital: whether the retail investor can lose all invested capital, where applicable, whether the PRIIP includes capital protection against market risk

-

- appropriate performance scenarios, and the assumptions made to produce them

-

- information on the tax legislation that applies

-

- Under a section titled “What happens if [the name of the PRIIP manufacturer] is unable to pay out?”, a brief description of whether the related loss is covered by an investor compensation or guarantee scheme

-

- Costs associated with the product

-

- Effect of all costs, including commission, on the return

-

- an indication of the recommended and, where applicable, required minimum holding period

-

- explanation of conditions and charges applicable on withdrawal

-

- information about the potential consequences of cashing in before the end of the term or recommended holding period, such as the loss of capital protection or additional contingent fees

-

- information about how and to whom a retail investor can make a complaint about the product or the conduct of the PRIIP manufacture.

-

The PRIIPs regulation specified the general requirements on the content of each section.

The European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) are required to develop Technical Standards specifying the details of the presentation and content of the KID, for adoption by the European Commission.

Appendix 3: Emergence of the “advice gap” in the UK market since the RDR

The ban on commissions and the introduction of a more transparent fee structure is likely to promote a two-tier market with a gap between the tiers; one tier for the masses who will need simple standardised products where the processes and administration can be automated as far as possible, with some online servicing. The other side of the market will be aiming towards the high net worth individuals who require complex products to meet their complicated needs. Advice will still be needed and they will be willing to pay for that advice.

This “advice gap” in the market is something we are starting to see in the United Kingdom, for example, in the at-retirement space, whereby wealthier retirees have access to various self-invested personal pension (SIPP)/drawdown options and there is not really much on offer for those who have very small pots, other than to take their pots in full or take out an annuity. Cass Business School recently concluded that as a result of the UK’s RDR, a UK investor with less than £61,000 in investment funds is no longer commercially viable for investment advisory services (note that ~75% of the UK adult population would have less than this amount to invest) (Clare, Reference Clare2013). As a result of these concerns UK regulators are responding, even indicating a willingness to consider a return to commission payments in some form for certain retail products (see Professional Adviser, 2016). Furthermore foreign regulators and commentators are also taking notice of these developments, for example, considering commenters on the US Department of Labor’s proposed Fiduciary Duty Rule, which would ban commissions on certain individual retirement account products including some variable annuities and fixed interest annuities, unless exempted subject to strict conditions (see Schoeff, 2014).

Appendix 4: Examples of illustration methodologies for POS disclosure in various markets

In many jurisdictions the disclosure of expected returns and potential risks to customers is required by the regulator. The minimum requirement is normally an illustration of benefits or outcomes under different scenarios (e.g. low/medium or base/high) and of the impact of charges on the customer’s outcomes. In certain markets, the minimum regulatory requirements have been developed further by the industry by disclosing and presenting more scenarios or stochastic projections. Below is a summary of some key market practices and other regulatory initiatives.

POS disclosure in the insurance, banking and securities sectors by the Joint Forum