Introduction

This study addresses the problematic character of flying a state, entity, religious, or foreign flag during wedding processions on streets and in parks in Bosnia and Herzegovina after the tragic war that ended in 1995. Flying identity flags in public places during wedding processions seems to confound the political task of keeping “a complicated, complex identity like Bosnia and Herzegovina together” (Banac Reference Banac1993, 139). The reason is, as Robert Shanafelt points out, that “Not only does the display of a flag suggest social solidarity, it simultaneously demands political deference” (Reference Shanafelt2008, 16). Through this wedding custom, families link themselves to an ethnic polis and an ethnic polis to families. The power of nationalism is in how it makes the family political and the state family, according to Hannah Arendt (Reference Arendt1958, 256). In this sense, the wedding custom exacerbates ethnic antagonisms. Michel Foucault asserts, “Power comes from below; that is, there is no binary and all-encompassing opposition between rulers and ruled at the root of power relations” (Reference Foucault and Hurley1978, 94). This popular, everyday cultural practice represents an unaddressed de-democratization force in the everyday lives of the nation’s citizens and politically disenfranchises the country’s inhabitants. This study investigates and measures with a representative survey study the degree to which the everyday wedding practice both ferments and does not ferment nationalism in a vulnerable society and dysfunctional state. The results indicate that it, in fact, is easy to overestimate the social and the political significance of the wedding procession. While the wedding custom gives nationalism an inflated sense of political significance, the survey results show the indifference of many respondents to the everyday practice. The national identity of being Bosnian rather an ethnic identity is more likely to be exemplified in this context. Paradoxically, hot nationalism and banal nationalism merge such that each seems to cancel the other out. The wedding custom is all too familiar to be anything but noticed (Billig Reference Billig1995).

First, we provide an account of the fatal and ominous shooting at a Bosnian Serb wedding in the central part of Sarajevo before the start of the war in 1992. Then, after a literature review framing the study’s conceptual arguments, we empirically investigate the degree to which the wedding custom exemplifies the power of nationalism with a clustered, stratified, random sample of 2,500 subjects over the age of eighteen drawn from the country’s entire population.

The wedding custom is a notable feature of everyday life in Bosnia and Herzegovina. To the question, “did you display a flag at your wedding?” 26.4 percent of those married in the representative survey answered yes – note that of those married, 73.6 percent answered no. Of the 26.4 percent who answered yes, 21.4 percent identified as Bosniak, 36.9 percent as Croat, and 30.4 percent as Serb. The custom is a transethnic one in a polyethnic society. To the question, “have you seen others display a flag at a wedding you were attending?” 59.4 percent of the survey respondents answered yes; and to the question, “have you seen others display a flag at a wedding at which you were not present (in public spaces)?” 87.7 percent answered yes.

We interpret the survey results in terms of demographic variables and construct comparisons of the different flags flown by ethnicity (different flags being either a state, entity, religious, or foreign flag where sometimes two are flown together). We analyze the survey results in terms of respondents’ attitudes and feelings toward flying identity flags in the public domain and political party affiliations, measuring the degree to which the cultural practice both does and does not exemplify the power of nationalism. How persuasively does flying identity flags exemplify nationalism in Bosnia and Herzegovina? How ominous is the following statement: “If nationhood is being flagged, then the routine reminders might also be rehearsals; the echoes of the past cannot be discounted as preparations for future time” (Billig Reference Billig1995, 125)?

Shooting at a Bosnian Serb Wedding

On Sunday March 1,1992, two major events happened before the outbreak of war on the 4th of April. The first was the referendum on Bosnia and Herzegovina’s independence from Yugoslavia, and the second was a shooting during a wedding of a Bosnian Serb couple, Milan Gardović and Dijana Tambur, killing the father of the bridegroom (Nikola Gardović) and injuring the Serbian Orthodox Priest (Radenko Miković) in downtown Sarajevo. Both events contributed to exacerbated tensions between ethnic groups and are presented as the “triggers” that led to war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Ančić Reference Ančić2004).

According to documentaries, the reason for interfering with the wedding ceremony was the flag of the Serbian Orthodox Church, accompanied by honking cars through the city and the singing of traditional Serbian songs. This information comes from the recorded testimonial of the shooter, named Ramiz Delalić aka Ćelo, who was originally from the Sandžak region, which straddles the border between Serbia and Montenegro where tensions between Serbs and Muslims were acute (Morrison Reference Morrison2016, 87). A month before the shooting occurred, the Sarajevo newspaper Oslobodjenje reported that Delalić was “implicated in a shooting and a rape and had received treatment at a Sarajevo psychiatric hospital” (Donia Reference Donia2006, 392).

The wedding celebration began in a residential area called Alipašino polje, where the flag bearer or barjaktar raised the flag of the Serbian Orthodox Church on their family’s balcony and attracted the neighbors’ attention. Traditionally, the barjaktar leads the groom’s wedding party from the groom’s house to meet the bride and her family. A rural custom is that if the barjaktar were challenged and his flag were stolen, the barjaktar would be required to buy back the flag that signifies the strength of the groom’s family. Traditionally the barjaktar was the eldest unmarried male in the groom’s family. In much of Yugoslavia such wedding processions are routinely accompanied by the honking of car horns and the discharging of firearms, attracting onlookers (Ančić Reference Ančić2004, 356).

The wedding party went to the Church of the Holy Transfiguration in Novo Sarajevo where a religious wedding took place. Participants stated some cars had been stopped a few times, but they did not consider it a serious threat. A wedding lunch had been planned at the oldest Serb-Orthodox church in Sarajevo (Ančić Reference Ančić2004, 355), and guests parked their vehicles not far from the church and decided to walk and celebrate the wedding on foot by wearing symbols of the Serbian Orthodox Church and singing, according to Delalić, offensive songs for members of other ethnic groups. Delalić stated that he and a couple of his friends had noticed a group of cars much earlier, and had been “provoked” to see what it was about. When they arrived at the place from where the wedding guests walked to the church, there was a confrontation between Delalić, his friends, and the wedding guests. Delalić admits that there was a shooting and that he was aiming in the direction of other people’s legs, but other witnesses claim that Delalić unambiguously aimed at and shot the bridegroom’s father in the back without hesitation. Although an ambulance soon arrived, the groom’s father could not be saved. Delalić and his friends got lost in the chaotic mass of people who were shocked at what had just happened.

The shooting transformed the wedding celebration into a tragedy and triggered a strong military reaction that was already preplanned. That night, members of Serbian paramilitary units, supported by the JNA, erected blockades throughout Sarajevo, cutting the city in half (Ančić Reference Ančić2004, 356). Some Bosnian Serbs regard Gardović as the first casualty of the Bosnian war, masking the aggression of nationalist Serbs in planning and starting a premeditated war.

Delalić went on to become a warlord who defended Bosnia and Herzegovina and organized the defense of Mount Trebević as commander of the 9th Mountain Brigade. After the war on December 8, 2005, Delalić, given pressure from the international community, was charged with one count of first-degree murder in relation to the wedding shooting. His trial started on February 14, 2005. On June 27, 2007, before his trial could be completed, Delalić was shot and killed by an unidentified gunman in Sarajevo.

The wedding procession was tantamount to a political march. Michael Billig (Reference Billig1995, 105) references in his study, Banal Nationalism, the concept of the ratified audience in Erving Goffman’s work on dramaturgy and the distinction it makes. The ratified audience here is the wedding party, the families and friends who are invited and come to the wedding celebration. There is also another audience, namely, the non-ratified audience. The non-ratified audience here is those who observe and hear on the streets and in parks what is being done for the ratified audience. The Serbian Orthodox wedding procession through the center of Sarajevo was meant as much as if not more for the non-ratified audience as the ratified audience. The wedding procession was a public speech act, where the intention was to have an effect on an audience. The shooting before the war was prescient and an example of what Craig Calhoun (Reference Calhoun, Skey and Antonsich2017) means when he writes, “Nationalism is available for political purposes and dramatic moments of mobilization only because it is produced and reproduced in banal and everyday forms” (19).

This incidence can be understood more clearly when compared to the political situation in Northern Ireland, where processions come to be perceived as political marches.

It is not the “right to march” that is being asserted, or a simple “celebration of culture”, as the Order [Protestant Orange Order in Northern Ireland] maintains. Marching through Catholic areas against the wishes of the local residents is about flaunting the symbols of Protestant supremacy and the culture of unionist domination. It matters desperately to the Orange Order to hold on to some sense of a past in which unionists controlled the economy, government, the civil service, the police and the media. (Garvaghy Residents cited in McManus Reference McManus2017, 418)

This situation in Ireland compares to the situation in Sarajevo when the wedding party marched with the religious flag of the Serbian Orthodox Church through Baščaršija, Sarajevo’s historic cultural center from the Ottoman period. Flying identity flags in the public domain evokes othering. C. P. McManus (Reference McManus2017) observes, “Othering is capable of mobilizing, at any given moment, large sections of the population around particular beliefs about both the in-group and the other” (41).

To take an extreme example, think of the ISIS black flag that was flown in Syria and Iraq during its military campaigns. The flag terrorized people in villages and on the land and was a means of asserting dominance, threatening violence, creating fear, and intimidating the population. Consider Under the Black Flag: At the Frontier of the New Jihad (Moubayed Reference Moubayed2015) in this regard. To state the problem clearly, “… differences, when codified and embedded in ‘unassailable’ belief systems, such as those associated with nationalistic fervor or fundamentalist political, economic, and religious systems, can provoke ethnic cleansing, genocide, and massacres sanctioned by dogmatic religious beliefs” (Marsella Reference Marsella2005, 653).

Think also of the QAnon flag flown by right-wing extremists in the United States and worn on shirts during pro-Trump rallies. Think of the confederate flag and its history of white supremacy flown during the violent attack on the United States capitol building in Washington in January 2021. The people who stormed the capital building while Congress was in session carried many flags. With the flag, a group defines itself as morally superior to those observing, and this superiority may be by virtue of race, class, religion, ethnicity, or history. As Émile Durkheim (Reference Durkheim and Field1995) notes, “The purpose of the image is not to represent or evoke a particular object but to testify that a certain number of individuals share the same moral life” (234). The dominance white supremacy and white nationalism sought at the United States capital building was found in the power of the flag.

The flag makes nationalism tangible. The flag comes to constitute the being of nationalism in that “the various beings whose form the totemic emblem represents, are held to be made of the same essence” (Durkheim Reference Durkheim and Field1995, 238). If the flag is taken out of the equation, the tangibility of nationalism dissolves. Durkheim (Reference Durkheim and Field1995) notes, “The clan is a society that is less able than any other to do without an emblem” (234). In this way, the flag sustains nationalism. Durkheim observes, “Take away the name and the symbol that gives it tangible form, and the clan can no longer even be imagined” (Reference Durkheim and Field1995, 235). The point is not that there would no longer be flags as symbols; the point is that the flag would no longer be a totem: “The emblem is not only a convenient method of clarifying the awareness the society has of itself: It serves to create – and is a constitutive element of – that awareness” (Durkheim Reference Durkheim and Field1995, 231). Nationalism is dependent upon the totemism of the flag in that it itself sustains nationalism.

Merging Family and State

What is the significance of flag power specifically in the context of a wedding ceremonies and how does it empower nationalism? Victor Turner (Reference Turner1964, 19) invites social scientists “to focus their attention on the phenomena and processes of mid-transition.” He theorizes that they “paradoxically expose the basic building blocks of culture just when we pass out of and before we re-enter the structural realm.” The private family event and the public political performance become linked in a liminal space. Both the wedding guests (the ratified audience) and the observing public (the non-ratified audience) are in a liminal space that Turner describes as betwixt and between. The wedding party is, on the one hand, a private family event and, on the other hand, a public event. According to Turner, this liminal space is an unrecognized crucial one for understanding the significance of cultural phenomena, and it helps frame the specificity of this study.

When Yugoslavia fell, it provided the political context in which nationalism grew leading to war, crimes against humanity, and genocide. Given this painful, contemporary history, it is natural to link the trust network of the family to an ethnic community rather than to a dysfunctional state that is fraught with corruption and ill-will (Skey Reference Skey2011). Linking the trust network of the family to an ethnic polis is “in response to unsatisfactory governmental performance” (Tilly Reference Tilly2004, 8).

Hannah Arendt provides a theoretical account that frames the problematic character of this practice in the everyday life of a politically vulnerable society and dysfunctional state. When identity flags are flown in the public domain during wedding ceremonies, the distinction between the private and the public realm is collapsed. The private and the public are fused.

The distinction between a private and public sphere of life corresponds to the household and the political realms, which have existed as distinct, separate entities at least since the rise of the ancient city-state; but the emergence of the social realm which is neither private nor public, strictly speaking, is a relatively new phenomenon whose origin coincided with the emergence of the modern age which found its political form in the nation-state. (Arendt Reference Arendt1958, 28)

Arendt says that erasing the distinction between the private and public sphere in modern times is pivotal to the creation of the nation-state. Displaying identity flags at weddings makes a private affair the vehicle with which to take a political stand. The wedding ceremony becomes a spectacle. “The spectacle appears at once as a society itself, as a part of society and as a means of unification. As a part of society, it is that sector where all attention, all consciousness, converges” (Debord Reference Debord and Nicholson-Smith1995, 12).

It is advantageous to have a trust network between families at weddings linked to the ethnic polis. The social capital of the network and its priority within the community is transferred to the ethnic community, and this empowers the ethnic community. In this way the ethnic polis builds a strong patronage system that leads to the de-democratization of the state. The antagonism between the democratic state and the patronage systems of different ethnic communities increases. What is diminished as a normative political value is “the equalization of resources and connections among potential political participants” (Tilly Reference Tilly2004, 20). Politics becomes enmeshed in family ties; patronage is buttressed in family trust networks.

Arendt’s (Reference Arendt1958) theorizing explains the political significance of the phenomenon in terms of nationalism.

The organic theories of nationalism, especially in its Central European version, all rest on an identification of the nation and the relationships between its members with the family and family relationships. Because society becomes the substitute for the family, “blood and soil” is supposed to rule the relationships between its members; homogeneity of population and its rootedness in the soil of a given territory become the requisites for the nation-state everywhere.” (256)

Flying identity flags during wedding ceremonies in public spaces establishes “an identification of the nation and the relationships between its members with the family and family relationships” (Arendt Reference Arendt1958, 256). The wedding procession becomes the petri dish on which nationalism grows.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, marriages establish culturally important affinal kinships as observed in the ethnographies of William Lockwood and Tone Bringa (Lockwood Reference Lockwood1975; Bringa Reference Bringa1995, 136–140). Marriages create prestigious social networks called prijatelji between the groom and bride’s families. Prijatelji has two meanings. One is friendship, the other is in-lawship or affines. The heritage of close affines is shared by the three largest ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina but is not so strong in neighboring countries (Doubt & Tufekčić Reference Doubt and Tufekčić2019). Andrei Simić reported that in Serbia relations by marriage are “more fragile” and “can be regarded in the moral sense as being rather weak” (Reference Simic1971, 64). Lockwood and Bringa’s ethnographies reported the opposite: In Bosnia and Herzegovina relations by marriage can be regarded in the moral sense as being rather strong. The kinship heritage reflects a trans-ethnic identity that is important and shared in a polyethnic society (Doubt Reference Doubt2014). Through flying identity flags at a wedding ceremony, this kinship structure is co-opted by an ethnic community and politicized. The family is linked to the political, and the political to the family.

It should be noted that in the state of Montenegro, another former republic of Yugoslavia that is also a polyethnic society, laws against publicly displaying the flag of another country without a permit exist. Montenegro’s rules are strict. In March 2020, a Turkish national was fined several hundred euros for displaying the Turkish flag without permission at a construction site in a coastal resort. The charge was violating the public order and peace (Kajosevic Reference Kajosevic2020).

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, there are similar laws that require flying the state flag next to an ethnic flag, but they are not enforced. One reason is there is no confidence in the national flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The flag was imposed in 1998 by the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina, Carlos Westendorp, after failed political agreements on the appearance of the national flag. Political officials in Bosnia and Herzegovina at the time had several proposals on the appearance of different flags that they could not agree on, which is why in 1998 the Office of the Higher Representative (OHR) set up a Westendorp Commission to select national symbols – the flag, the coat of arms and the anthem – of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Even after the Westendorp Commission’s proposal was made, no agreement was reached on the Bosnia and Herzegovina flag in the Parliament, which is why the High Representative used his powers and made the final decision. The issue of the Bosnia and Herzegovinian flag was not resolved within the Bosnia and Herzegovina Constitution, but imposed by the Bosnia and Herzegovina Flag Law, primarily in order for Bosnia and Herzegovina to have a national flag for the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano.

While the manifest purpose of the Westendorp Commission was to support national unity, its unintended consequence was to open the door even wider to the political influence of nationalism and its power in linking the family and the state. The state flag is an abstract (colonizer’s representation of the country) because the state played no direct role in its creation. The international community’s utilitarian enabling of the dysfunctional state of Bosnia and Herzegovina vis-a-vis the capricious rule of ethnic politicians compounds a difficult political situation. Despite international efforts to make the country’s flag common to all, it is subject to political upheaval that is divisive.

Let us now interpret and analyze the results of the study’s survey asking to what degree flying identity flags at weddings does and does not ferment nationalism. We address this question from the advantage point of a macro perspective that provides a fuller, more objective, and, hopefully, more honest account. The empirical survey raises what Max Weber (Reference Weber, Gerth and Mills1946) calls inconvenient facts for the understanding the effectiveness of flag power in fermenting nationalism: “And for every party opinion there are facts that are extremely inconvenient, for my own opinion no less than for others” (147).

Research Design

Survey questions about the displaying of flags at weddings were included fall 2018 in an omnibus survey in Bosnia and Herzegovina conducted by Mareco Index Bosnia. Mareco Index Bosnia has experience conducting survey research for universities, embassies, and governmental agencies and is a member of Gallup International, following prescribed guidelines regarding ethical inquiry, transparency, and protection of human subjects. A clustered, stratified, random sample of 2,500 subjects over the age of eighteen was drawn from the country’s population, including the entities Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska as well as Brčko District, a random selection of cantons, and rural and urban populations. The sampling followed the random route technique for selecting households for face-to-face interviews. The technique of nearest birthday was used to select an individual within the household for participation in the survey.

The survey asked the following questions: “did you display a flag at your wedding,” “was a flag displayed at a wedding you attended,” and “did you observe a flag being displayed at a wedding you did not attend?” Respondents were then asked which flags were displayed at their weddings or the weddings they observed, that is, whether the flags were a state, entity, religious, or foreign flag. The respondents were next asked what their attitudes as well as their feelings were toward the wedding custom, that is, whether they felt angry, proud, resentful, intimidated, indifferent, envious, amused, sad, excited, uncomfortable, or embarrassed when they saw others fly a flag during their wedding. The question of which political party the respondent would vote for if an election were held today was also posed.

The respondents who identified their ethnicity as Croat was 14.8 percent (n=371), Bosniak 54.0 percent (n=1,351), and Serb 29.3% (n=733).Footnote 1 The proportions of the sample mirror the proportions of the country’s population. The respondents who identified as Other was 1.8 percent (n=45), which does not mirror the proportions of the population, which is estimated at 10.0 percent or higher (Dicosola Reference Dicosola, Benedizione and Scotti2016). The percentage of respondents married was 58.5, single 29.7, divorced 3.2, and widowed 8.7% (N=2500). Demographic information such as gender, age, education, marital status, and ethnicity was included in the survey. The survey was conducted in Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian. The questionnaire in Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian and English, an SPSS file with the survey’s results, and a technical report on the survey technique are available on Open ICPSR for further study (Doubt Reference Doubt2021).

This study’s use of the survey data is primarily descriptive; the purpose is to demonstrate objectively and empirically the question of to what degree the power of nationalism is realized in this wedding practice. We heed the statement, “Meaningful research tells a story with some point to it, and statistics can sharpen the story” (Abelson Reference Abelson1995, xiii). We do not analyze variables as dependent and independent variables as if testing for a causal explanation, as is done in experimental research. Neither do we employ inferential statistics to confirm a hypothesis. While we conduct chi-square tests to show statistically significant variations vis-à-vis socially significant variations, this use of the chi-square test falls within the domain of descriptive rather than inferential statistics. We focus on what Weber calls meaningfully adequate explanations. Weber (Reference Weber1947, 99) pointed out, “If adequacy in respect to meaning is lacking, then no matter how high the degree of uniformity and how precisely its probability can be numerically determined, it is still an incomprehensible statistical probability.”

We stress that the unit of analysis is not the individual, but the ethnic group with which individuals choose to identify. Our analysis of nationalism in everyday life is top-down rather than bottom-up. The study’s probability sample allows us to observe ethnic groups and measure the social practices of individuals as a group. Weber (Reference Weber1947, 102) provides justification for this approach when he writes, “These concepts of collective entities which are found both in common sense and in juristic and other technical forms of thought, have a meaning in the minds of individual person, partly as something actually existing, partly as something with normative authority. This is true not only of judges and officials, but of ordinary private individuals as well.” The concept of ethnic identity has meaning in the minds of individual people; it exists in the social world and it is something with normative authority, which is the interest of the study. Does flying identity flags at weddings increase the normative authority of nationalism which fuses family and state? The study asks how the normative authority of nationalism both is and is not expressed through flag power and thus dysfunctional or not dysfunctional for a democratic society.

Results and Interpretations

We first report the survey results and their association with the demographics provided in the omnibus survey. In response to the question, “did you display a flag at your wedding?” 26.4 percent of the respondents who were married answered yes. The majority of the survey’s respondents who were married, 73.6 percent, did not fly a flag at their wedding. This point is important. Displaying a flag in the public domain during a wedding assumes an inflated sense of power; an immense minority appears to represent a tiny majority.

Age

We find that age is a significant variable where we report here just the row total for those married who displayed a flag at their wedding.

Of the 26.4 percent who were married and who displayed a flag at their wedding, 53.3% of those between 18–19 displayed a flag at their wedding. This vitality of the younger age group gives the wedding custom an exaggerated meaning. This age group’s weddings occur more recently and are the most recently observed in the public domain. This crosstab also shows that the older generations were less likely to have flown a fly at their wedding; the custom appears to have been less common during the Yugoslav socialist era (see table 1).

Table 1. Displayed Flag at Wedding by Age.

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, X2 (4, N = 1758) = 138, p < .001.

Education

The variation in terms of education is interesting. The result is unexpected when looking at the education level of those who displayed a flag at their wedding.

In Sarajevo and Tuzla, people refer to this wedding custom as primitive: “Are flags then, artificial extensions of the signals given off during primate displays of dominance and subordination” (Shanafelt Reference Shanafelt2008, 21)? The results indicate that the group with the highest education is the largest proportion of those who fly flags at their wedding (see table 2). The survey raises an inconvenient fact for the common-sense opinion on the streets in urban areas. We think here of Gustave Le Bon’s The Crowd. The appeal, the behavior, and the mind of the crowd as reflected in the power of nationalism as exemplified in the flying of flags is a social and political equalizer (Le Bon Reference Le Bon1982).

Table 2. Displayed Flag by Education

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, X2 (3, N = 1758) = 59, p < .001.

Type of Settlement

Another variable of interest is whether the respondents lived in a rural or urban community.

Although married respondents in urban areas are more likely to display a flag at their wedding than respondents in rural areas, the difference is small. It is difficult to make much of this variable because after the war many inhabitants in urban areas were originally from rural areas. The wedding custom appears to transcend the class differences that are reflected in the rural and urban populations of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is the small, statistically insignificant difference that is sociologically significant (see table 3).

Table 3. Displayed Flag by Geographic Code

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, X2 (1, N = 1758) = 1.56, p > .21

Religious Beliefs

Another variable of interest is the nature of the participants’ religious beliefs. The survey asked participants to characterize the nature of their religious belief with different categories.

The respondents who described the nature of their religious belief as conservative are more likely to display a flag at their wedding. The chi-square test for independence, however, shows that there is not a statistically significant relation between nature of religious belief and whether married respondents flew a flag at their weddings (see table 4).

Table 4. Displayed Flag by Nature of Religious Belief

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, X2 (7, N = 1758) = 8.7, p = .274.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity, the focus of this study, is the primary variable of interest for this study of nationalism in everyday life.

Bosniaks are less likely to fly a flag at their wedding than either Croats or Serbs. Croats are more likely to fly a flag at their wedding than Bosniaks and Serbs. The differences are statistically significant (see table 5). We now will construct crosstabulations focusing on ethnicity as an explanatory variable.

Table 5. Displayed Flag by Ethnicity

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, X2 (3, N = 1758) = 31.9, p < .001.

Types of Flags

Respondents were asked whether the flag flown at their wedding was a state, an entity, a religious or a foreign flag. We report the results for each type of flag separately and then interpret the results in response to this question in terms of respondents’ ethnicity. At the same time, we describe the different flags and their particular historical and political backgrounds.

State Flag

The results when respondents were asked whether the state or national flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina was flown at their wedding are revealing.

Married Bosniaks are significantly more likely to display the state flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina at their wedding than married Croats or married Serbs, and married Croats are more likely to display the state flag than married Serbs are. In the wedding custom of displaying the state flag during a wedding procession, the identity of being Bosnian in Bosnia and Herzegovina is exemplified. The practice is strongest among Bosniaks (90.0%), but there is a significant proportion of Croats (46.8%) and Serbs (34.4%) who exemplify the national identity of being Bosnian in this way, which is an inconvenient fact for the nationalists in these communities (see table 6). The representative survey raises inconvenient facts for understanding the effectiveness of flag power in fermenting nationalism. During the Yugoslav period that ended in the late eighties, if a flag was flown at a wedding, it would have been the Yugoslav state flag.

Table 6. Displayed National or State Flag at their Wedding by Ethnicity

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, X2 (3, N = 464) = 127.7, p < .001.

Two state flags, in fact, might be flown. The first is the official state flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The flag was imposed in 1998 by the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina, Carlos Westendorp, after failed political agreements on the appearance of the national flag (see figure 1). Despite the international efforts to make the state flag common to all, it is subject to political upheaval, since many deny it, especially in the entity Republika Srpska, where it is rarely, if ever, displayed. This flag is most recognized by Bosniaks who will display the flag at weddings.

Figure 1. State Flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina

When a Bosniak cafe owner in Janja, a town in Republika Srpska, placed the Bosnian state flag in the window of his cafe on November 25th in 2017 to mark the national historic day, government officials from Republika Srpska came and told him to remove the flag, saying the day is remembered only in Bosnia’s other entity, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and not in Republika Srpska (Lakic Reference Lakic2017). November 25, during the middle of World War II in 1943, is an historic day in Bosnia’s history because on this day the decision was made to establish Bosnia and Herzegovina as a constituent part of the Yugoslav federation, a republic in equal standing with the other republics. The historical event affirmed Bosnia and Herzegovina, a multiethnic society that defies the nation-state model, as a historical and unitary entity parallel and equal to the other republics in the Yugoslav federation.

The second state flag that might have been flown is the original flag of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

After the 1992 referendum and the declaration of independence from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, this flag became the national symbol of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The lilies on the flag symbolize the continuity of Bosnian statehood, which dates back to medieval Bosnia. The lily motif had been present on the coats of arms used by the bans and kings in medieval Bosnia, and it became highly favored among the Bosnian people. The lily motif is present on Bosnian medieval tombstones called stećci, jewelry, books and as a design and decorative element on canvas and architecture (see figure 2). The appearance of the new flag of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was widely accepted among Bosniaks, but not so much by the other ethnic groups. Under this flag, resistance was given to the forces carrying out destruction and the killing of inhabitants in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which made the flag a symbol of the opposition and the heroism of the people defending Bosnia and Herzegovina. Here is why many Bosniaks continue to promote and cherish the original national flag. Most members of other ethnic groups (Bosnian Croats and Bosnian Serbs) consider the flag with lilies as exclusively a Bosniak flag. While the original national flag was replaced in 1998, many Bosniaks remain emotionally connected to the flag. The flag can still be seen – often with the current state flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina – at Bosniak weddings.

Figure 2. Original Flag of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Entity Flag

The survey asked married respondents whether they displayed an entity flag at their wedding ceremony. Republika Srpska has an entity flag. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is an entity, does not have an entity flag because the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina ruled that an entity flag for the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina would be discriminatory. Understandably, Serbs are more like to display an entity flag (see table 7).

Table 7. Displayed Entity Flag at Their Wedding by Ethnicity

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, X2 (3, N = 464) = 67.8, p < .001.

One reason why Bosnian Serbs are more closely connected with the symbols of the Republic of Serbia is the fact that the flag of the entity of Republika Srpska has the same order of colors.

Republika Srpska is a Bosnia and Herzegovina entity in which the majority is Serbian as result of genocide during the war from 1992–1995, euphemistically called ethnic cleansing. The flag and the coat of arms were created in 1992, and in its original appearance lilies were incorporated, which were also imitations of the coat of arms of Serbia (see figure 3). However, when Bosniaks began to identify themselves with the lilies on the Bosnia and Herzegovina flag, the lilies from the coat of arms of Republika Srpska were removed, although they remained on the Serbian coat of arms and flag. In 2007, the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina ruled that the symbols of both entities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (the anthem, the coat of arms, and the flag of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the coat of arms and the anthem of Republika Srpska) were unconstitutional because they discriminated against one of the constituent people in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Only the entity flag of Republika Srpska remained in use because, as mentioned, in the opinion of the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, its appearance did not include elements of discrimination. Throughout the whole of the entity of Republika Srpska, there are virtually no state symbols for Bosnia and Herzegovina. The entity symbols of Republika Srpska prevail. The political sentiment behind secession and seeking an ethnically pure entity after purging non-Serbs from the territory during the war is reflected in the following observation: “Perhaps a more secure position—within a stable state with fully ‘banalised’ nationalism—from which they could comfortably claim privileged membership and the right of ‘management of national culture and territory’ would be advisable because it would alleviate the tensions and open up the space for more democracy” (Spasić Reference Spasić2017, 44). Privileged membership, though, does not alleviate tensions in modern societies and does not open up space for democracy. The problem is that privileged membership and democracy are incompatible.

Figure 3. Entity flag of Republika Srpska in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Religious Flag

Married respondents were asked whether they displayed a religious flag at their wedding.

Table 8. Displayed a Religious Flag at Their Wedding by Ethnicity

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, X2 (3, N = 464) = 64.9, p < .001.

Bosniaks are more likely to display a religious flag than Croats or Serbs. Those who identified as Other were more likely to display a religious flag than Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs (see table 8).

The religious flag that Bosniaks would commonly fly at weddings is the flag of the Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

This flag refers to the Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but it is worth mentioning that it is also used by other Islamic communities and groups in other countries as a symbol of affiliation with Islam as a religion. The green color of the flag represents one of the colors of Islam, and the crescent moon and the star are its symbols (see figure 4). If the wedding has a religious ceremony, Bosniaks frequently fly this flag, sometimes beside one of the two above mentioned flags, on cars at weddings. Of married Bosniaks who flew flags at their wedding, 46.9 percent flew the state and religious flag together, expressing identity with their country as well as their faith. The practice exemplifies a syncretism that is generally characteristic of Bosnian culture: “Syncretism calls analytic attention to creative blending rather than the maintenance of cultural distinctions” (Strong Reference Strong2006, 586). The syncretism presupposes not the purity but the incompleteness of the traditions that are blended and their neediness of each other (Doubt & Tufekčić Reference Doubt and Tufekčić2019, 13).

Figure 4. Flag of the Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The religious flag that Bosnians Serbs may display at a wedding is the flag of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

This flag also consists of three colors: red, blue and white. In the middle is a cross with four “fire striker” shapes, and according to some interpretations, these are the four letters S, which point to the principle of Serbian unity and harmony. The flag of the Serbian Orthodox Church was connected to an incident between Bosniaks and Serbs at the Serbian wedding in Sarajevo in 1992 (see figure 5). Of the Bosnian Serbs who flew flags at their weddings, 10.5 percent flew the state flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina and their religious flag together.

Figure 5. Flag of the Serbian Orthodox Church

Foreign Flag

Respondents were asked whether they displayed the foreign flag of another country at their wedding in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The practice shows a nationalist loyalty to a country other than Bosnia and Herzegovina and disloyalty to Bosnia and Herzegovina. The practice is provocative. In Nations and Nationalism, Ernest Gellner (Reference Gellner1983, 6) provides the popular political rationalization for the creation of a nation-state through genocidal war and the current efforts to hold a binding referendum on the succession of Republika Srpska: “Nations and states are not the same contingency. Nationalism holds that they are destined for each other; that either without the other is incomplete and constitutes a tragedy” (6). Flying the flag of another state during a wedding procession in Bosnia and Herzegovina expresses this sentiment. Nationalism’s commitment to creating a nation-state is strengthened when it makes the family the political and the state the family.

Table 9 shows the results of the total number of married respondents who displayed a foreign flag at their wedding by ethnicity.

Table 9. Displayed the Flag of Another Country at Their Wedding by Ethnicity

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, X2 (3, N = 464) = 89.3, p < .001.

Of those who flew flags at their wedding, Croats are most likely to display the flag of another country (see table 9). The foreign flag that Bosnian Croats would have flown at their wedding is the Republic of Croatia.

The flag of the Republic of Croatia was adopted after the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1990 and consists of three colors: red, white, and blue, and the coat of arms of the Republic of Croatia in the middle of the flag. These colors reflect the history and traditions of the country of Croatia because these colors were also found in their traditional symbols. The coat of arms on the flag has motifs of a blue crown and a red and white chessboard, which has been used since the 15th century. The chessboard symbolizes the Croatian people, regardless of their place of residence, which makes it is a popular symbol often used by Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina (see figure 6).

Figure 6. State Flag of the Republic of Croatia

During the period of the so-called Independent State of Croatia (NDH), a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, the law stipulated that the first field on the chessboard was white, which turned it into a symbol for the fascist group called Ustaše. After the defeat of the so-called the Independent State of Croatia and Nazi Germany, the white field on the chessboard was replaced with red, which is now prescribed by the current Constitution of the Republic of Croatia. The question of the color on the chessboard, nevertheless, remains topical and is still debated. Which variant, the color white or the color red, is traditional, legitimate, and constitutional? Whether or not the color white on the chessboard is traditional, it is unconstitutional in the Republic of Croatia and perceived by many, both in Croatia and beyond its borders, as provocative.

The foreign flag that Bosnian Serbs would have flown during wedding processions is the flag of the neighboring Republic of Serbia. The current appearance of the flag of the Republic of Serbia was adopted in 2004, and it was standardized in 2010 with no significant changes to its appearance (Spasić Reference Spasić2017, 36).

It consists of three colors: red, blue, and white, and the coat of arms of Serbia: a two-headed white eagle on a red shield with a crown above it. The crown represents the sovereignty and the state, and the cross on it signifies that only God is above it. The double-headed eagle represents the harmony between the state on one side and the church on the other side. The importance of the church is symbolized by the “Serbian cross” which is on the eagle shield. It is interesting to note the two heraldic lilies that are on the coat of arms, which could be associated with medieval Bosnia (see figure 7). Lilies are present in other cultures and civilizations as well. Bosnian Serbs use the Serbian flag more often than the Bosnia and Herzegovina flag, which they seldom use at weddings.

Figure 7. State Flag of the Republic of Serbia

Nationalist Bosnian Serb leaders want to hold a referendum on the secession of Republika Srpska from the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Republika Srpska was created through genocide and war crimes, purging non-Serbs from villages and towns where in some cases non-Serbs had been a majority. The legitimacy of Republika Srpska as an entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina was regretably established by the Dayton Peace Accords. The entity was artifically constructed in Dayton in 1995; historically and culturally, the entity had always been an authentic and integral part of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Variation in Type of Flag Flown

To provide an overview of the variation in the type of flag flown, we note that the highest proportion of flags flown at weddings is the national flag.

Table 10. Which Flag was Flown at Wedding

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, N = 464.

This loyalty could be characterized as “authentic patriotism” in the public and private realm when the two realms are merged (Goode Reference Goode2017). This national identity in Bosnia and Herzegovinia is overlooked in contemporary political discourse. The anti-synthetic logos and dysfunctional structure of the Dayton Accords are alien to the country it purports to hold together and breaks apart. While religious traditions inform the ethnic differences in Bosnia-Herzegovina, ethnic personalities and historical heritages are grounded in overlapping and common cultures exemplified in everyday life (Lovrenović Reference Lovrenović1996). Since the Dayton Accords reifies the ethnic identities of Bosnians and ignores the country’s national personality, it keeps Bosnians separate and inserts a void between them. The Dayton Accords fails to recognize and support the cultural and historical solidarity of Bosnia and Herzegovina grounded in the principle of unity in diversity (Mahmutćehajić Reference Mahmutćehajić2003). Despite intractable political circumstances, the national identification with Bosnia and Herzegovina remains strong – in fact, stronger vis-a-vis ethnic nationalism, which is demonstrated in the flying of the state flag during wedding ceremonies (see table 10).

A polyethnic society, as the survey results indicate, does not need to be a conflicted society, despite the arguments and practices of the political elite. Holding cultural heritages in common, the ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina constitute an integrated society that is politically unrecognized. After the war that ended in 1995, Bosnia and Herzegovina became a politically divided nation in a way it never truly was before. One overlooked casualty of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina is its collective commitment to a pluralistic and integrated society. Unconscionable violence and vicious propaganda were brought to bear against her heritage, cultural convictions, and social practices. The tragedy after the war is that while the nation has a trans-ethnic history and culture, there are few functional trans-ethnic institutions to support, respect, and sustain these historical traditions, which makes it difficult for Bosnia and Herzegovina to re-establish the trans-ethnic institutions she needs.

Like Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina was a republic of Yugoslavia. The political legitimacy of Bosnia and Herzegovina vis-à-vis other republics was established during World War II (Malcolm Reference Malcolm1996, 180-181). While Bosnia and Herzegovina was more of a polyethnic society than the other republics, the difference should not mask the fact that the other republics were also polyethnic societies. Yugoslavia held together its six polyethnic republics and two autonomous provinces under the slogan "Brotherhood and Unity," a political principle which denied privileged membership according to ethnicity.

Attitudes Toward Flying Flags

Another question on the survey was: Are your feelings toward flying flags at weddings positive or negative? Respondents answered on a Likert scale very positive, positive, neither positive nor negative, negative, and very negative. We report results by ethnicity, keeping in mind that all respondents are included in the crosstabulation.

Table 11. Attitude Toward Flying Flag at Weddings by Ethnicity

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, September 2018, X2 (12, N = 1758) = 88.5, p < .001).

To provide a summary, for Bosniaks, the spread is bimodal: a significant proportion is very positive and a significant proportion is very negative. At the same time, the spread trends toward very negative. For Croats and Serbs, the spread trends toward very positive. For Other (n=29), the spread tends toward very negative, reflecting the perspective of vulnerable minorities (see table 11).

The largest proportion for each ethnic group, however, is neither positive nor negative. To summarize, the results show significant support as well as significant resistance toward the way in which nationalism appears to be fermented in the displaying of flags at weddings. More importantly, the results show significant indifference, suggesting the banality in the everyday practice of nationalism that is exemplified in the wedding custom (Billig Reference Billig1995).

Another set of questions asked how respondents felt when they saw others display a flag at their wedding. Respondents were asked whether they felt angry, proud, resentful, intimidated, indifferent, envious, amused, sad, excited, uncomfortable, or embarrassed. Table 12 reports the results of those answering yes to this set of questions.

Table 12. Feelings Toward Seeing Others Display a Flag at Wedding

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, Sarajevo, September 2018, N = 2500.

The results raise inconvenient facts. The two feelings that received the highest proportion of yes answers were proud, 25.6 percent, (reflecting the effectiveness of the power of nationalism) and indifferent, 52.4 percent (reflecting the ineffectiveness of the power of nationalism). Of the 25.6% who said yes to having feelings of pride when seeing a flag flown at a wedding, 21.23 percent were Bosniak, 38.6 percent Croat, and 27.8 percent Serb. It is more important to note that 74.4 percent responded no to having feelings of pride when seeing a flag flown at a wedding (see table 12). Banal nationalism is too familiar to be noticed. Hot nationalism is too noticeable to make a difference. Of the 52.4 who said they felt indifferent when seeing a flag flown at a wedding 48.8 percent were Bosniak, 53.8 percent Croat, and 57.9 percent Serb. It is easy to overestimate the social and political significance of flying flags at wedding processions. While the wedding custom gives nationalism an inflated sense of political and historical significance, the majority respondents show indifference to the practice in their everyday lives.

Political Parties, Flying Flags at Weddings, and Nationalism

One question on the survey asked, if a political election were held today, which political party would you vote for. To this question, 24.6 percent (n = 615) said they would not vote, 20.1 percent (n = 520) said they did not know, and 13.7 percent (n = 343) said none. The results show the lack of engagement in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the democratic processes. The phenomenon represents an unaddressed de-democratization force in the everyday lives of the nation’s citizens and shows the political disenfranchisement of the country’s inhabitants.

In terms of its political system and state structure, Bosnia and Herzegovina is dysfunctional (Bieber Reference Bieber2002). A General Framework Agreement for Peace signed in Dayton, Ohio framed Bosnia and Herzegovina as a single country made up of two entities; the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska are tantamount to mini-states within the country. The Dayton Accords are tantamount to a bureaucratic strait jacket: a state with two entities, three constitutive peoples, one district, ten cantons, and a rotating tripartite presidency. The Croatian leader, Franjo Tuđman, and the Serbian leader, Slobodan Milošević (two war criminals who fermented the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina from outside Bosnia and Herzegovina) ratified the Dayton Accords for Bosnia and Herzegovina. Nikola Kovač (Reference Kovač2007), ambassador to France for Bosnia and Herzegovina, noted, “The international community tolerated the initiators of conflict and took the side of the stronger (not the victim), in the belief that the ‘lords of war’ were the only interlocutors” (3).

The Dayton Accords insists on the “exact” narration of the ethnic composition of the country. The Dayton Accords classify Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs as constituent peoples. The Dayton Accords not only ignore but also disenfranchises the greater than ten percent of the citizens in the country who are not members of one of these ethnic groups and who are labelled Other (Dicosola Reference Dicosola, Benedizione and Scotti2016). Participation in both the House of Representatives and the House of Peoples, the two chambers of the state’s parliament, as well as the Presidency, is restricted to members of these three ethnic groups and regulated on the basis of a balanced representation between the three ethnic groups. Two members of the collective presidency cannot be from the same ethnic group. Each member of the collective presidency from a different ethnic group then rotates as president of the country.

To make the matter even more awkward, a Bosnian Serb living in the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina rather than the Republika Srpska cannot be a candidate for the country’s presidency; only a Bosnian Serb living in Republika Srpska can be a candidate for the country’s presidency. Moreover, a Bosnian Serb living in the Federation can only vote for the Bosnian Serb living in Republika Srpska who is running for the presidency. The status of the Bosnian Serb living in the Federation is Other as is the status of the greater than ten percent of Bosnian citizens who are not members of one of the three major ethnic groups. Likewise, a Bosniak or a Bosnian Croat living in Republika Srpska cannot be a member of the country’s presidency. The status of the Bosniak or Bosnian Croat living in Republika Srpska, like the status of citizens who are not members of the three major ethnic groups, is Other. The Dayton Accords discriminates against people’s political rights to equal and full citizenship.

The Dayton Accords privileges the electoral advantage of ethno-politicians in each of the three ethnic groups (Mujkić Reference Mujkić2008). Dervo Sejdić and Jakob Finci, who are Roma and Jewish, Bosnians who are neither Bosniak, Croat, or Serb and who are leading citizens in terms of their civic responsibility, filed and won a lawsuit charging discrimination at the European Court of Human Rights. Nothing has changed more than ten years after Europe’s highest human rights court condemned the Dayton Accords as discriminatory, giving citizens outside the three ethnic groups second-class status. The Dayton Accords give meaning without understanding and understanding without meaning.

To reify this perversity, the Dayton Accords bans someone who does not wish to declare an ethnic identity from running for the country’s highest office. Ms. Azra Zornić, like Dervo Sejdić and Jakob Finci, filed a case of political discrimination and human rights violation to the European Court of Human Rights and won her suit. Since Zornić refused to declare an ethnic identity and simply declared herself a citizen of Bosnia-Herzegovina, she is denied the right to run for the country’s highest office. Her case is not mentioned as much as the one with Sejdić and Finci, and one reason may be because a woman rather than a man is suing. Her lawsuit, however, is more consequential and deeper in that she is suing on behalf of not her ethnicity and minority rights, but on behalf of her citizenship as a Bosnian which she shares with all Bosnians, the very concept the Dayton Accords belies. The category of Other trumps and then erases the category of citizenship and the possibility of authentic patriotism in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Nationalism fills the void. When the Dayton Accords insist on the “exact” narration of the ethnic composition of the country, the political structure becomes disconnected with the transethnic social reality and political history of the state. The Dayton Accords, as much as anything, ferment nationalism. Any modern state that had to live with this constitution would disintegrate into political chaos.

It is no wonder that to the question, if a political election were held today, which political party would you vote for, 24.6 percent (n = 615) said they would not vote, 20.1 percent (n = 520) said they did not know, and 13.7 percent (n = 343) said none. Twenty-seven political parties were listed that could be chosen. Only 28.2 percent (n = 731) indicated that they would vote for one of these 27 parties. Only eight political parties, had more than one percent of the respondents saying they would vote for it if an election were held today.

These eight political parties that received more than one percent of the respondents’ support are described and then collapsed into two binominal groups, one for the nationalist political parties (independently of the three ethnic affiliations) and the other for the multinational political parties (see table 13). Those who said they would vote for a political party but not one of the eight most popular are therefore not included in table 13.

Table 13. Eight Most Popular Political Parties

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, September 2018.

The nationalist parties follow the consociational model which conceals the anterior idea that peaceful coexistence is ultimately based on the lasting subordination of one ethnic group by another. Since no ethnic group in Bosnia and Herzegovina is large enough to dominate and achieve this fantasized power situation as is the case in the nation-state model, consociation is the default situation and undesired substitute (Mujkić Reference Mujkić2008). By way of contrast, the multinational parties follow the integrationist and civil society model, namely, that peaceful co-existence is based on the principle of social and political equality, equal rights for all citizens.

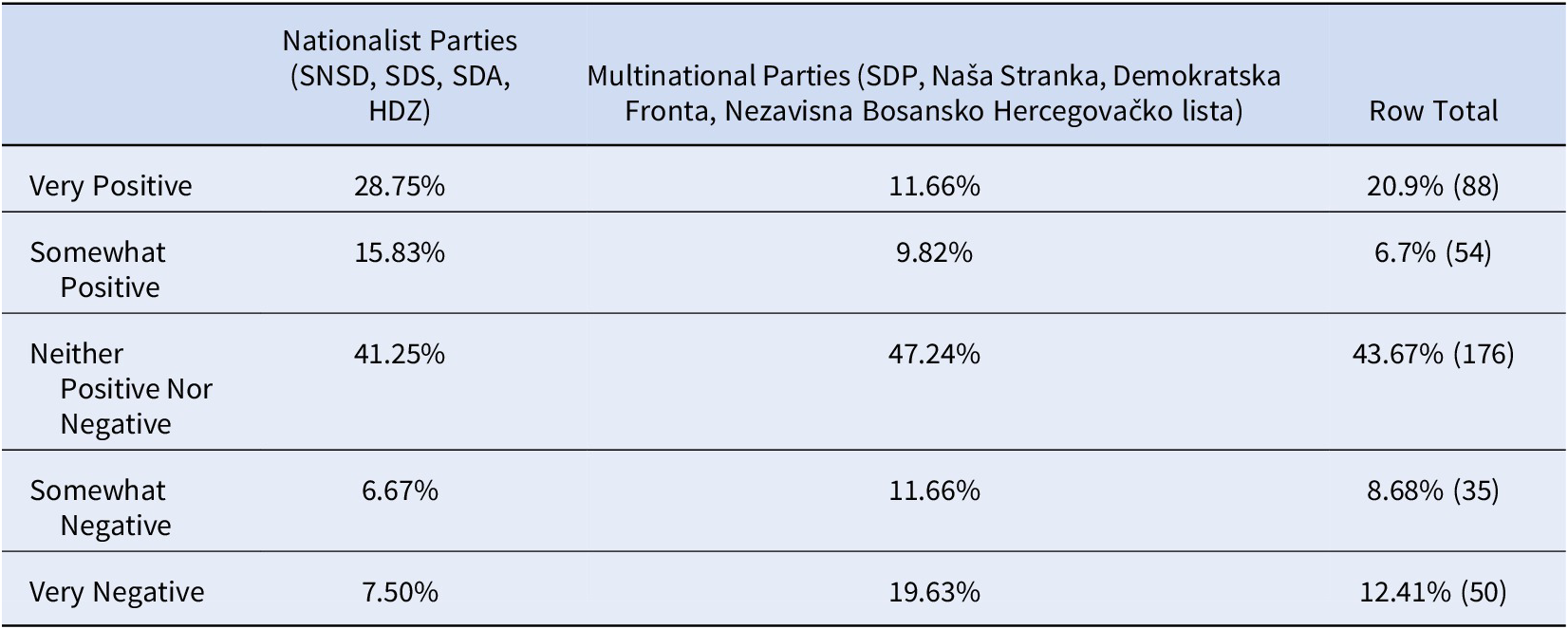

We report the results comparing the two groups of political parties by attitude toward flying flags at weddings. As noted, for the purposes of this study measuring whether or not nationalism is reflected in the flying of flags at weddings, we collapsed the eight most popular political parties according to their political platform, one group being nationalist political parties (regardless of ethnic identity) and the other group being multi-national political parties.

Table 14. Attitude Toward Flying Flags at Weddings by Nationalist and Multinational Parties

Source: Mareco Index Bosnia, September 2018, X2 (16, N = 1462) = 48.5, p < .001.

N = 1462.

The results show a strong association between nationalist political parties and positive feelings toward flying flags at weddings and a strong association between multi-national political parties and negative feelings toward flying flags at weddings. At the same time, the highest proportion in both groups was neither positive nor negative, revealing the political indifference toward flying flags during weddings in public spaces (see table 14).

Conclusion

In Yugoslavia, Bosnia-Herzegovina had stood as a model for the other republics of polyethnic solidarity. The Partisan formulation during World War II was “Without Bosnia there is no Yugoslavia and without Yugoslavia there is no Bosnia” (Palermo Reference Palermo, Benedizione and Scotti2016, 159). Francesco Palermo turns this logic on its head to formulate a description of the current political reality: “Multiethnic Bosnia has ceased to exist when multiethnic Yugoslavia collapsed” (Reference Palermo, Benedizione and Scotti2016, 159). The result of the war is formulated as having been the cause of the war, which masks the causes of the war. Nationalists use this logic to explain the war, whose intention was not only genocide but sociocide, murdering Bosnian society itself (Doubt Reference Doubt2021).

The Dayton Accords established a rigid, iron cage structure for a polyethnic society. Using the paradox of the fish soup, Palermo (Reference Palermo, Benedizione and Scotti2016, 160) characterizes the attempt this way: “It is relatively easy to turn an aquarium into a fish soup, but it is impossible to do the opposite … once a multiethnic society has exploded and conflicts have erupted, it is utopian to expect legal instruments to re-establish it.” As this survey study shows, Palermo’s skepticism is overstated. Today fish swim and live in the polyethnic aquarium that is Bosnian society. Ivo Banac critiques Palermo’s common scholarly understanding that compares the Yugoslav national identity to the national personality of the inhabitants in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

If Bosnia were a collectivity of separate entities, then it would have been a mini-Yugoslavia. But it is not that. Bosnia is a historical entity which has its own identity and its own history … I view Bosnia as primarily a functioning society which Yugoslavia never was. My question is how does one keep a complicated, complex identity like Bosnia and Herzegovina together? (Banac Reference Banac1993, 139)

Bosnia and Herzegovina is not a mini-Yugoslavia with a supra-ethnic identity reflecting Yugoslavism, nor is it a collective of separate cultural or ethnic entities. Bosnia and Herzegovina has a national personality reflective of its unique history. The country’s national personality is grounded in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s enigmatic mixture of historical epochs: a distinctive medieval period from the 13th to 15th centuries, the Ottoman Empire starting in the 15th century, the Austro-Hungarian Empire during the 19th century, and communist Yugoslavia during the 20th century.

Bosnia-Herzegovina remains a polyethnic society, albeit a deeply wounded one. The former Yugoslav republics also remain polyethnic societies even after being established as nation-states where one ethnic group enjoys privileged membership. In these former republics, there is still nostalgia for their society’s polyethnic character. It is inaccurate to say that since Yugoslavia after the death of Tito could not remain a united country, neither could Bosnia-Herzegovina. Bosnia in unrecognized ways remains a polyethnic society, despite the cracks caused by the war from 1992–1995, the dysfunctional Dayton Peace Accords, the ethnic politicians in each ethnic group, and the international community’s Kafkaesque control of the country. While flying identity flags during weddings in public spaces appears to empower nationalism by fusing family and state, the actual impact of the wedding custom is inflated given the counter national identity of being simply Bosnian in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable assistance of Nermina Mujagić, Jerry G. Pankhurst, Aida Hadžiavdić-Begović, Muhamed Sušić, and Adnan Tufekčić.

Financial Support

Wittenberg University, Faculty Research Grant

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2021.58.