In the years following the release of the WHO’s 2004 Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health, the global soft drink industry has embraced self-regulation as a key component of its strategy to position itself as ‘part of the solution’ to obesity(Reference Nestle1,2) . Some governments and public health stakeholders argue that self-regulation demonstrates the capacity and willingness of the packaged food and beverage industry to be ‘part of the solution’ to obesity, whereas others argue that self-regulation is a smokescreen to delay or distract from the development of more effective public health regulations(Reference Moodie, Stuckler and Monteiro3–Reference Hawkes and Buse9).

Public health researchers’ concerns about the political dimensions of the packaged food and beverage industry’s self-regulation are partly a consequence of their experience with the tobacco industry. Insights from the tobacco industry’s internal documents released during litigation have led some scholars to characterise corporate self-regulation as a political strategy to deliberately delay or pre-empt regulation(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks10). Without access to the same cache of internal industry documents, public health researchers have relied on comparisons between tobacco and food industry political behaviours and assumed similar intentions(Reference Moodie, Stuckler and Monteiro3,Reference Brownell and Warner7,Reference Chopra and Darnton-Hill11–Reference Dorfman, Cheyne and Friedman16) . The present study uses a data set of industry documents published over a 19-year time frame, including archives of industry websites, to provide insight into the political motivations driving the soft drink industry’s development of self-regulation.

The paper uses a case study of the Australian soft drink industry’s Commitment Addressing Obesity and Other Health and Wellness Issues (hereafter the Commitment) to critically analyse how the food industry uses self-regulation to influence the political environment. We examine the circumstances under which the Australian Beverages Council (ABC) developed the Commitment and the strategies it used to promote it as an alternative to government regulation. Our analysis reveals the emergence of obesity on the ABC’s political agenda and the evolution of its use of self-regulation to pre-empt government regulation.

Background

Self-regulation in response to obesity

In their review of obesity-related self-regulation, Ronit and Jensen(Reference Ronit and Jensen17) differentiate between three areas of research focus: (i) the content of self-regulation; (ii) the effectiveness of self-regulation; and (iii) the interactions between self-regulation and government regulation. One conclusion from their review and other studies is that food industry commitments are significantly weaker than the objectives set by public health or government policies(Reference Ronit and Jensen17–Reference Lang, Rayner and Kaelin21). Additionally, food industry commitments are often poorly or inconsistently implemented, limiting their efficacy(Reference King, Hebden and Grunseit22–Reference Watts, Masse and Naylor24). A further finding is that self-regulation differs considerably between companies, industries and countries in terms of its scope and efficacy(Reference Hawkes and Harris5,Reference Ronit and Jensen17,Reference Sacks, Mialon and Vandevijvere19,Reference Lang, Rayner and Kaelin21) . These comparative studies offer insights into the degree of consistency or inconsistency between different pledges as well as evaluating the strengths and weakness of pledges.

In considering why self-regulation differs between companies, industries and countries, Hawkes and Harris(Reference Hawkes and Harris5) argue that variations between country-specific political and regulatory pressures can explain some of the differences and inconsistencies between industry commitments. Jensen and Ronit(Reference Jensen and Ronit25) also suggest that companies facing significant government and community pressure, such as soft drink companies, have a greater incentive to engage in self-regulation. Scholars scrutinising the political incentives for and impacts of self-regulation argue that the threat of regulation catalyses food industry self-regulation(Reference Nestle1,Reference Hawkes and Harris5,Reference Sharma, Teret and Brownell6,Reference Jensen and Ronit25–Reference Panjwani and Caraher27) . Some public health scholars claim that self-regulation serves an offensive, political purpose to deliberately undermine public health goals(Reference Moodie, Stuckler and Monteiro3,Reference Wiist28,Reference Freudenberg29) . Several studies find that food industry self-regulation may ‘stall’, ‘procrastinate’, ‘undermine’, ‘pre-empt’, ‘avert’, ‘deflect’, ‘prevent’ or ‘avoid’ efforts to develop and implement effective government regulation(Reference Nestle1,Reference Moodie, Stuckler and Monteiro3–Reference Sharma, Teret and Brownell6,Reference Dorfman, Cheyne and Friedman16,Reference Jensen and Ronit25,Reference Mello, Pomeranz and Moran26,Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Wate30) . These studies portray self-regulation as a strategic initiative designed to respond to regulatory threats and diffuse unwanted government action.

Despite public health concerns that self-regulation may (perhaps deliberately) undermine or pre-empt government regulation, there are relatively few case studies that examine country- or industry-specific pressures provoking soft drink industry self-regulation. Three notable exceptions include: (i) Nestle’s(Reference Nestle1) history of self-regulation on marketing to children and school beverage sales; (ii) Mello et al.’s(Reference Mello, Pomeranz and Moran26) case study of the development of school beverage guidelines; and Sharma et al.’s(Reference Sharma, Teret and Brownell6) analysis of the context in which self-regulation originates.Footnote * These studies detail the political and regulatory context in which industries develop self-regulation to shed light on the political motivations underpinning self-regulation and the intersections between public and private policy making.

Mello et al.(Reference Mello, Pomeranz and Moran26) offer perhaps the only specific case study of obesity-related soft drink industry self-regulation that details how a voluntary agreement pre-empted the ongoing development of more binding regulations. Drawing on insider accounts from public health advocates involved in negotiations with the beverage industry, the case study documents how the soft drink industry strategically launched voluntary guidelines to pre-empt the development of stronger regulatory measures. While some lauded the guidelines as significant progress, public health scholars and investigative journalists found that the agreements were far weaker than the previously negotiated guidelines(Reference Mello, Pomeranz and Moran26,Reference Blanding35) .

Analysing the political dimensions of corporate self-regulation

Studies scrutinising the political motivations and consequences of the food industry’s self-regulation are part of a wider body of scholarship that analyses the political strategies or ‘playbook’ of other powerful industries(Reference Nestle1,Reference Brownell and Warner7,Reference Dorfman, Cheyne and Friedman16,Reference Wiist, Stuckler and Siegel36) . Public health researchers have drawn parallels between the political strategies of the food, pharmaceutical, alcohol and tobacco industries – the so-called commercial determinants of health(Reference Buse, Tanaka and Hawkes15,Reference Kickbusch, Allen and Franz37–Reference Hastings39) . In 2014, Savell et al.(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks10) developed a corporate political activity (CPA) framework to classify the set of strategies the tobacco industry uses to influence and shape its political environment in ways favourable to its industry. This framework has been subsequently adapted to classify and monitor the CPA of the alcohol and food industries(Reference Savell, Fooks and Gilmore40,Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Sacks41) .

In their food industry CPA framework, Mialon et al.(Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Sacks41) classify the development and promotion of alternatives to policies (such as voluntary codes, self-regulation and non-regulatory initiatives) as ‘policy substitution’. Despite explicit reference to the ‘development’ and ‘promotion’ of self-regulation, thus far there has been little systematic analysis of these two facets of policy substitution in analyses of food industry CPA. Mialon and colleagues’ analyses of food industry CPA have focused on documenting the existence of self-regulation, but these studies have not examined the motivations that led the soft drink industry to develop self-regulation or the strategies the industry used to promote its self-regulation to policy makers(Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Wate30,Reference Mialon and Mialon42–Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Allender44) . While the existence of self-regulation is a necessary component of policy substitution, it does not sufficiently explain why and how the food industry uses the strategy.

As noted in the beginning of the present paper, public health researchers of the tobacco industry have access to a vast trove of internal industry documents, which have revealed how the tobacco industry used self-regulation as part of a wider political strategy to counter the threat of regulation(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks10,Reference Fooks, Gilmore and Smith45,Reference Mamudu, Hammond and Glantz46) . Dorfman et al.(Reference Dorfman, Cheyne and Friedman16) note that instead of drawing on internal industry documents, public health researchers identify similarities between tobacco and food industry political strategies (such as the development of self-regulation)(Reference Moodie, Stuckler and Monteiro3,Reference Brownell and Warner7,Reference Chopra and Darnton-Hill11–Reference Dorfman, Cheyne and Friedman16) . However, these studies provide few details of food industry motivations. Absent too from most research of soft drink industry self-regulation is an industry perspective. As discussed earlier, a notable exception is Mello et al.’s case study of school beverage guidelines(Reference Mello, Pomeranz and Moran26).

To address these limitations, the present paper uses a case study of the self-regulation developed by the ABC to explore the role that political interests played in shaping the development and promotion of self-regulation. This Australian case study uses publicly available web archives, yearbooks and other documents created by the ABC to understand the association’s motivations to develop self-regulation and its strategies to promote it.

Methods

For the present paper, we used a case study of the development and promotion of the ABC’s self-regulation to analyse the political dimensions of corporate self-regulation. We analysed a data set of 165 publicly available industry documents published by the ABC including twelve commitments and position statements, eleven annual reports, seven sets of minutes from annual general meetings, twenty newsletters, twelve yearbooks, eight written policy submissions, two oral submissions, fourteen industry-funded papers and reports, and seventy-nine archived webpages.Footnote * These documents spanned a 19-year time frame between 1998 and 2016. Documents were downloaded from the ABC’s website (http://www.australianbeverages.org); yearbooks were sourced from Australian government libraries; and archives of the ABC’s website were sourced using the Wayback Machine (a not-for-profit digital archive) and downloaded from the ABC’s two websites, http://web.archive.org/web/*/softdrink.org.au/ (1998–2008) and http://web.archive.org/web/*/http://www.australianbeverages.org (2004–present). The Wayback Machine allows the public to access historical website content and presents a relatively new data source that can complement existing data sets(Reference Arora, Li and Youtie47–Reference Lomborg50). To avoid bypassing key documents, one author manually examined the first archive from each month with archives.

Data analysis occurred in two phases that broadly correspond with what the CPA literature refers to as the development and promotion of self-regulation(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks10,Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Sacks41) . First, we examined the development of the ABC’s self-regulation, which occurred between 1998 and 2006, culminating in the launch of the Commitment. We chronologically documented the ABC’s policy precursors to the Commitment and the different motivations voiced by the ABC for developing self-regulation and engaging in corporate political activity. Second, we examined how the ABC promoted the Commitment following its official launch, covering the period between 2006 and 2016. We focused on two promotional strategies: (i) funding research to demonstrate policy efficacy; and (ii) writing policy submissions. In our discussion, we consider some of the ways that the development of self-regulation amplifies other corporate political strategies. We also draw on theories of the policy process to help interpret and explain the political influence of voluntary self-regulation.

Results

Development of self-regulation

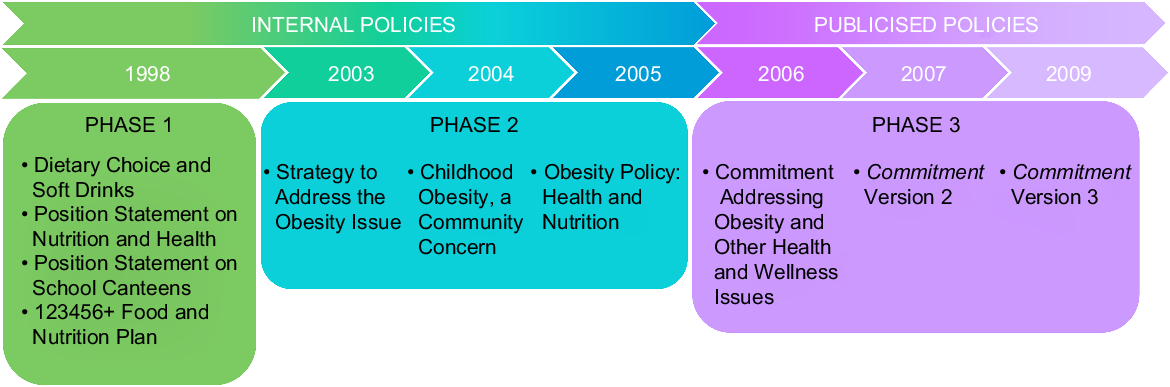

Based on our analysis of historical documents produced by the ABC, we differentiate between three distinct phases of the ABC’s development of self-regulation. Figure 1 highlights the key policy documents produced by the ABC during each phase.

Fig. 1 The Australian Beverage Council’s nutrition and obesity policies and strategies, 1998–2009

Phase 1: obesity becomes an issue for the soft drink industry (1998–2001)

In 1998, obesity did not feature heavily on the ABC’s political agenda. The ABC instead focused on opposing container deposit schemes and addressing health concerns about caffeine(51). While the ABC did not identify obesity as an issue, it voiced concern that schools might ban sugary drinks and noted that some state guidelines had placed sugary drinks in the ‘not recommended’ list(52).

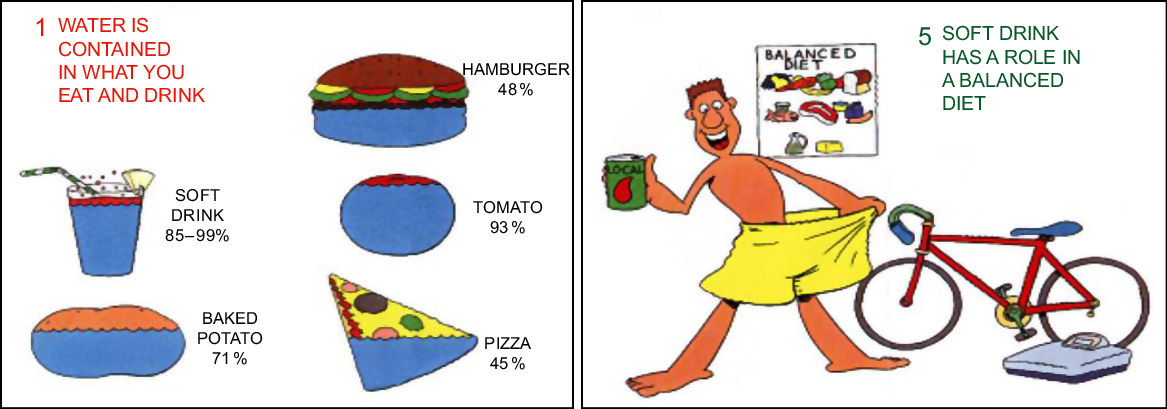

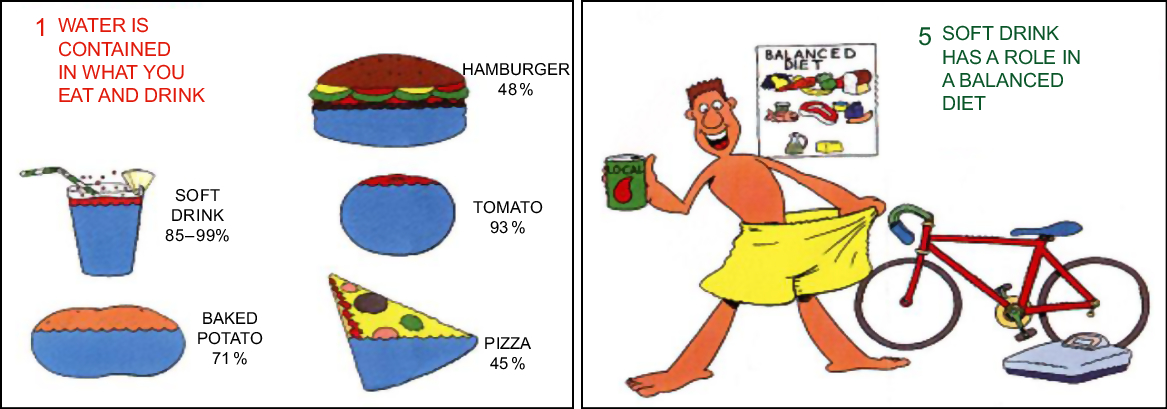

On its website, the ABC argued that ‘there is no such thing as a “good” or “bad” food – only good or bad eating habits’ and ‘sound nutrition does not result from eliminating a single food from the diet, but rather upon eating a variety of foods in moderation and staying physically active’(53). It also published a ‘Liquids for Living’ brochure on the student section of its website, which emphasised the role of soft drinks in a ‘balanced diet’ (Fig. 2)(54).

Fig. 2 Selections from the Australian Beverage Council’s ‘Liquids for Living’ brochure

During this time, the ABC published its first nutrition policy titled Dietary Choice and Soft Drinks(51). This policy took a defensive position, emphasizing the diversity of the ABC members’ portfolios and claimed that these beverages ‘meet the dietary choices of all consumers and make a positive contribution to their lifestyle’(51). This policy also noted that the industry would provide ‘adequate information to assist consumers in making informed choices’ but offered no specific commitments regarding labelling, reformulation, marketing to children, education programmes or stakeholder engagement(51).

In addition to developing policy positions, the ABC noted the importance of maintaining ‘ongoing active involvement in the health and nutrition community debate’ and the need to ‘do a better job at getting our message across’(51,53) . In 1999, it restarted its Public Affairs Committee, Government and Opinion Leaders Contact programme, to ‘develop good relations’ and increase contact with ‘leaders in government, regulatory affairs and nutrition and health’(55).

Phase 2: the soft drink industry considers responses to obesity (2002–2005)

Obesity emerged as a key issue for the Australian soft drink industry in 2002, when the Australian Health Ministers established a National Obesity Taskforce. Following the 2003 publication of Healthy Weight 2008, the ABC published its first media report acknowledging that childhood obesity was a serious issue requiring industry and government cooperation and expressing its interest in working with the government to be ‘part of the solution’(56). As the prospect of government regulation in response to obesity gained political traction, the ABC raised concerns that if it did not ‘participate in standards development, governments and consumer advocacy groups [would] set standards without industry input’(57).

In 2004, the ABC participated in three childhood obesity forums and accepted an invitation from the New South Wales Department of Health to be part of an industry reference group for school canteen guidelines(57). In response to proposed canteen guidelines banning soft drinks in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland in 2005, the ABC sent a letter to all primary schools in Australia outlining its ‘longstanding’ voluntary pledge to limit marketing in primary schools(58). ABC’s vice-president briefed the Commonwealth’s inquiry into establishing a national school canteen framework and its Public Health Committee was in ‘ongoing discussion’ with the Commonwealth Department of Health(59).

In addition to participating in the development of government policies, the ABC also worked to solidify its own commitments. In November 2005, the ABC and the Australian Food and Grocery Council agreed to develop a policy framework for marketing to children as well as sector and sub-sector key performance indicators(60). Following this meeting, the ABC’s chief executive officer met with the federal Parliamentary Secretary for Health to discuss the commitments of the ABC and its major members(60). In 2005, the ABC set out its first specific commitments that positioned the industry as part of the solution to obesity (Table 1). In contrast to its earlier policies, the ABC identified actions that its members would take to address obesity.

Table 1 The Australian Beverages Council’s first commitment to be part of the solution to obesity(118)

Phase 3: the soft drink industry promotes its solution to obesity (2006)

In April 2006, the ABC hosted a meeting of the International Council of Beverage Associations. At this meeting, it noted that industry associations in the USA and Europe had developed self-regulation on marketing to children and sales of soft drinks in schools, which prompted the ABC to consider its own self-regulation(61).

The ABC’s Board commissioned its Public Affairs Committee to review all ‘industry health, nutrition & school canteens policies’ before the 10th International Congress on Obesity, which was to be hosted in Sydney that September(61). The ABC also worked with other industry associations to ensure a coordinated approach to its commitments. Together with the New Zealand soft drinks association, it established a 600 ml standard serving size. It also worked with the Australian Food and Grocery Council on the development of the Daily Intake Guide(62). The ABC and Australian Food and Grocery Council jointly launched their labelling system at Parliament in November 2006, closely following the government’s first consideration of a proposal for a traffic light labelling scheme in Australia(62–64). The launch was endorsed by the Dietitians Association of Australia and officiated by the Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry and the Parliamentary Secretary for Health(65).

The ABC strategically timed and monitored the launch of its Commitment Addressing Obesity and Other Health and Wellness Issues(63) . It launched the Commitment with a press release one week before the Congress on Obesity with the aim to ‘minimize negative publicity during the congress’(62,63) . The ABC and its members then attended the Congress to help defend soft drinks(66). According to the ABC’s media analysis, ‘the positive stories during the Congress provided clear indication that the Council’s “Commitments” policy helped to mitigate negative publicity … In some stories the Council’s guidelines were portrayed as an example for other food and beverage sectors in the battle against obesity’(59). The ABC also met with government officials to discuss its Commitment, noting that the Shadow Minister for Health ‘complimented the Industry on our new Obesity Commitments Policy and action taken to date’ and had a ‘very good understanding of our Industry’s issues’(67).

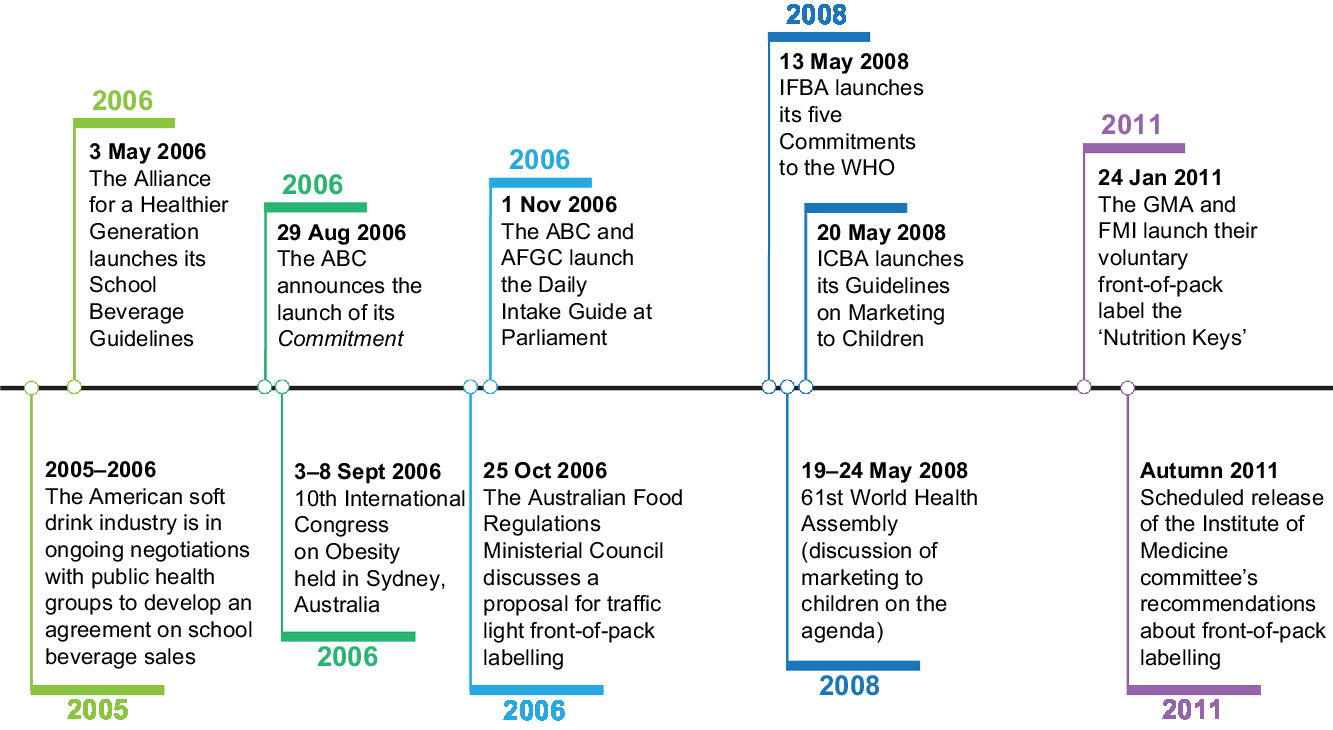

The timeline in Fig. 3 shows when the ABC launched its self-regulation and locates the launch within the relevant policy context. It also shows the launches of some of the food and beverage industry’s self-regulation internationally. This timeline illustrates how the launch of self-regulation often occurs during ongoing policy discussions or before the anticipated launch of government policy. We elaborate on this strategy in the ‘Discussion’ section.

Fig. 3 Timeline of launches of corporate self-regulation (ABC, Australian Beverages Council; AFGC, Australian Food and Grocery Council; IFBA, International Food and Beverage Alliance; ICBA, International Council of Beverages Association; GMA, Grocery Manufacturers Association; FMI, Food Marketing Institute)

Promotion of self-regulation

Funding research

Our analysis identified fourteen industry reports and publications funded by the ABC since the launch of the Commitment in 2006 (Table 2).

Table 2 Papers and reports funded by the Australian Beverages Council

ABC, Australian Beverages Council; CSIRO, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation.

While the exact amount that the ABC paid for these research papers, reports and infographics was rarely disclosed specifically, according to its annual reports, between 2006 and 2015 the ABC spent $AU 343 573 on consultants and $AU 372 329 on issue management. The ABC most frequently funded research showing that Australians had decreased consumption of sugary beverages, for example the two peer-reviewed papers published in Nutrition and Dietetics (Reference Levy and Tapsell68,Reference Levy and Shrapnel69) . The ABC did not take explicit credit for the decline in soft drink consumption in its publications. However, it occasionally included a section highlighting its self-regulatory initiatives (with the implication that it played a role)(70). By focusing on the evidence, the ABC’s publications likely appeared more neutral or balanced. The perception of neutrality or transparency was important to the ABC, which noted that, ‘the Committee was conscious to ensure these findings were both the positives and negatives from the survey, ensuring a theme of openness about the work’(71).

The ABC worked to ensure the credibility of its research in several ways. It funded two studies that were published in the peer-reviewed journal of Nutrition and Dietetics (Reference Levy and Tapsell68,Reference Levy and Shrapnel69) , and the lead author of the 2007 paper presented a poster at the Dietitians Association of Australia’s annual conference that year(72). By funding research, the ABC created the opportunity to collaborate with Australian health professionals and foster relationships with academic researchers affiliated with credible research organisations in Australia such as the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Flinders University and the University of Wollongong.

In 2010, the ABC developed an outreach programme to promote ‘The role of beverages in the diet of Australian children’. This programme took the author of the report, as well as the ‘leading academic’ who peer-reviewed the report, to fifteen meetings with key opinion leaders across Australia(71). The ABC estimated that the report was shared with 150 people from government, media, public health and non-governmental organisations, and noted that, while it was challenging to measure industry success from the outreach programme, it offered the ‘opportunity for the Council, and CEO [chief executive officer], to actively engage with KOLs [key opinion leaders] in this space’(71). The outreach programme also publicly affiliated the ABC’s research with a highly respected scientist who had worked with the National Health and Medical Research Council and CSIRO. In this way, the ABC worked to position itself as an expert resource for policy makers on the changing beverage consumption patterns of Australians.

Policy submissions

The ABC made written submissions to the development of at least eight key Australian policies between 2006 and 2016(73–80). The chief executive officers of the ABC also presented evidence to the 2008 Australian Senate Inquiry into Obesity and the 2016 New South Wales Inquiry into Childhood Overweight and Obesity(81,82) . Coca-Cola South Pacific(83,84) also made submissions to the National Preventative Health Taskforce and Blewett Review that referred to the ABC’s Commitment. Table 3 lists the written submissions made by the ABC that refer to its Commitments policy.

Table 3 Written submissions to key nutrition polices from the Australian Beverages Council

NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; ABC, Australian Beverages Council; ICBA, International Council of Beverages Association.

The ABC made three key arguments in support of self-regulation in its policy submissions. The first argument centred around the public health outcomes of the ABC’s self-regulation and asserted that, since the desired public health outcomes had already been achieved (or had achieved significant progress), further regulation was unnecessary. To support this claim, it presented data from studies it had funded about decreased Australian consumption of sugary drinks(Reference Levy and Tapsell68,Reference Levy and Shrapnel69,Reference Hendrie, Baird and Syrette85) . The ABC rarely disclosed its role in research funding.

The ABC’s second argument was that its industry members had proactively responded to concerns about its products. The ABC emphasised the expansive nature of its self-regulation, describing it as a ‘raft of voluntary initiatives’(77). It also referred to its policy audits to demonstrate the ‘substantial’, ‘entrenched’ and ‘widespread implementation of the initiatives’ by member companies(73,78,79) . The ABC framed the voluntary nature of its commitments as evidence of the soft drink industry’s benevolent nature, highlighting that the industry has ‘willingly participated’, ‘voluntarily committed’ and ‘[listened] and [adapted] to consumer needs’(78,80) . The ABC also argued that widespread implementation of its self-regulation justified maintaining the industry’s self-regulation in lieu of other government alternatives. In some cases, the ABC argued that its self-regulation ‘negated the need for any legislation in so far as beverages are concerned’(78).

The ABC’s third argument highlighted its interest in further dialogue with policy makers and the opportunity to ‘contribute to collaborative actions’(79). The ABC welcomed the proposed development of a National Preventative Agency and the ‘recognition that effective controls will require “working with the food and beverages industries”’(73) (emphasis original). The ABC expressed interest in partnerships and co-regulatory approaches as well(73,79) . Further, the ABC met with health and government stakeholders to discuss its Commitment and claimed that most of the stakeholders had endorsed the ABC’s policy on marketing to children or ‘provided suggestions for improvement’(73). In addition, the ABC regularly hosted its board meetings in Canberra and invited government officials to attend or give presentations. It noted that these meetings provided ‘valuable opportunities for the industry to liaise with government’(86). At other points the ABC estimated that it annually engaged with ‘approximately 50 stakeholders’ as part of its issue management agenda(87).

The ABC’s three arguments made in its policy submissions all supported its overarching contention: that the initiatives outlined in its self-regulation were a sufficient policy response. While not the focus of the present paper, the specific initiatives that the ABC endorsed in its Commitment focused predominantly on offering more beverage choices, information and education(88). By focusing its attention on initiatives that require consumer behaviour change, the ABC’s self-regulation implicitly frames obesity as an issue of personal (as opposed to government) responsibility. While presenting its industry as ‘part of the solution’ to obesity, the ABC strategically focused on initiatives requiring minimal changes to the business status quo.

Discussion

Our analysis of the ABC’s historical yearbooks and website archives offers a window into the emergence and ascent of obesity on the Australian soft drink industry’s political agenda. We observed a distinct shift from a defensive, reactionary response to obesity to a more overtly proactive approach that centred around voluntary self-regulation. The difference between the ABC’s rhetoric in its earliest nutrition statements and its 2006 Commitment illustrates the evolution of its approach to obesity. Whereas its 1998 statement on nutrition and health emphasized why soft drinks were not part of the problem, its 2006 Commitment focused on how soft drinks were part of the solution to obesity. The ABC’s transition away from a denial and negation strategy towards one of proactive policy development and engagement is consistent with international research documenting a shift in industry frames about obesity. Following 2006, the American food industry rarely made the argument that obesity was not a public health problem(Reference Nixon, Mejia and Cheyne89). 2006 was also the year that the food and beverage industry launched self-regulatory codes around the world(Reference Hawkes and Harris5,Reference Carter, Mills and Lloyd23,Reference Mello, Pomeranz and Moran26) . These national codes of conduct mark the emergence of a more coordinated response to obesity and the growing unity of the food and beverage industry’s response.

The range of different obesity policies targeting sugary drinks raises questions about how the industry attempts to promote its self-regulation as an alternative to different policy proposals(Reference Pomeranz90,Reference Thow and Hawkes91) . Both preceding and following the launch of its Commitment, we found that the ABC promoted its self-regulation to a wide assortment of stakeholders through a variety of methods including holding meetings with government officials and health organisations, writing letters to schools, participating in policy development, briefing inquiries, attending conferences, disseminating industry-funded research, writing policy submissions, as well as providing information on its website. While the soft drink industry lobbied to promote its self-regulation, we also observed a reciprocal relationship where the ABC’s self-regulation helped it to gain access to policy stakeholders and key opinion leaders in government and public health, similar to the tobacco industry’s efforts to re-establish access to policy makers by asking for ‘feedback’ on its corporate social responsibility initiatives(Reference Fooks, Gilmore and Smith45).

In addition to promoting its self-regulation to policy stakeholders, the ABC funded research that it then used to support its claim that self-regulation played an instrumental role in reducing soft drink consumption in Australia and that, consequently, further regulation was unnecessary. The ABC’s claim that further regulation is unnecessary is similar to the ‘regulatory redundancy’ arguments of the tobacco and alcohol industries in response to proposed regulation impacting their industries(Reference Savell, Gilmore and Fooks10,Reference Savell, Fooks and Gilmore40,Reference Martino, Miller and Coomber92) . While scholarly research corroborates the ABC’s claims that consumption of sugary drinks in Australia is declining at a population level, the crux of the ABC’s ‘regulatory redundancy’ claim is that its self-regulation played an instrumental role in this decline(Reference Popkin and Hawkes93). The Australian soft drink industry’s voluntary initiatives may have contributed to a reduction in sugary drink consumption; however, their impact remains subject to analysis. The drivers of dietary patterns and change are complex and public health interventions targeting sugary drink consumption are by necessity multifaceted(Reference Pomeranz90,Reference Thow and Hawkes91,Reference Myers, Fig and Tugendhaft94–Reference Lang, Barling and Caraher96) . Further, international evaluations have found that, despite being premised as momentous, industry commitments have essentially taken credit for pre-existing shifts in the market(Reference Mello, Pomeranz and Moran26,Reference Ng, Slining and Popkin97) . For example, in the USA, evaluations of the soft drink industry’s energy reduction pledge found that an energy reduction preceded the commitment and similar outcomes would have likely occurred without the industry initiative(Reference Ng, Slining and Popkin97).

Our findings suggest that the timing and context of the launch of self-regulation play an important role in the CPA strategy of policy substitution (see Fig. 3). For example, both the International Food and Beverage Alliance and the International Council of Beverage Associations unveiled marketing commitments during the 2008 World Health Assembly when the WHO was considering proposals to address diet-related diseases(98). In one of the ABC’s yearbooks, the International Council of Beverage Associations discussed the impact of the launch of its Guidelines for Marketing to Children, claiming that, ‘this policy was especially important at the 2008 World Health Assembly as calls for more stringent government regulation were muted by the industry’s voluntary commitment’(99). Other international studies show that when faced with the prospect of regulation, the food industry deliberately launches self-regulation prior to or during policy consultations to diffuse political momentum(Reference Mello, Pomeranz and Moran26,Reference Brownell and Koplan100) .

The idea that self-regulation can diffuse political momentum can be understood as the ‘politics of non-decision-making’(Reference Bachrach, Baratz and Haugaard101). By taking some steps to address the problem of obesity, self-regulation may decrease the perceived urgency of the problem. Kingdon(Reference Kingdon102) notes that frequently the passage of any government legislation on the issue diminishes attention to the issue, and that some political strategists might ‘prefer not to have legislation, because then it keeps attention focused on the problem’ (emphasis original). Critics of incremental policy change have raised similar concerns about the tendency for policy developments to lull the public into thinking the problem has been addressed(Reference Coglianese and D’Ambrosio103). This draws attention to the importance of how (and by whom) problems are defined in policy debates(Reference Weiss104,Reference Bacchi105) . Porter and Ronit(Reference Porter and Ronit106) argue that industries expend considerable effort in defining a policy problem as one that can be addressed by ‘incremental change in best practice’. We discussed earlier how the ABC’s Commitment essentially takes credit for market trends that match public health objectives. Arguably, the industry’s commitment to energy labelling demonstrated the most significant deviation from the business status quo. However, this too was softer than other policy alternatives(Reference Carter, Mills and Lloyd23,Reference Maubach, Hoek and Mather107–Reference Kelly, Hughes and Chapman109) .

By launching self-regulation, the ABC not only minimised the extent to which obesity is perceived to be a problem in need of a policy solution, but also the extent to which its industry is seen as part of the problem. While some of the ABC’s initiatives were launched as alternatives to a specific anticipated policy, in other cases self-regulation functioned more as public relations. The ABC timed the launch of its Commitment to coincide with the 10th International Congress on Obesity, during which the Sydney Principles on marketing to children were launched(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Lobstein110). By preceding the event, the soft drink industry created an opportunity for its members to interact with public health stakeholders and promote its self-regulation during the Congress. The ABC noted that its self-regulation was held up as an example for other industries to follow and received praise from key policy stakeholders including the then Shadow Minister of Health, Nicola Roxon. Praise for soft drink industry self-regulation has also been forthcoming overseas(Reference Nestle1,111,112) . By analysing the context in which the food and beverage industry launches self-regulation, we can observe that the timing of these launches is strategic, not only to head off anticipated government policy, but also to soften anticipated industry criticism.

We can understand the link between public relations and policy substitution by considering the experience of the tobacco industry. Named the ‘merchants of doubt’, the tobacco industry spent decades contesting the health harms of its products, a strategy that eventually led government officials to view the industry as untrustworthy(Reference Fooks, Gilmore and Collin113,Reference Oreskes and Conway114) . The soft drink industry has learned from the tobacco industry’s experience and uses self-regulation and other corporate social responsibility initiatives to avoid similar denormalisation and ostracism(Reference Dorfman, Cheyne and Friedman16). While the soft drink industry has learned from the tobacco industry’s experience, so too have public health advocates, who remain suspicious and watchful of industry political activity(Reference Buse, Tanaka and Hawkes15,Reference Paarlberg, Mozaffarian and Micha115–Reference Stuckler and Nestle117) . To an extent, the praise that the beverage industry received for launching self-regulation reflected the initial optimism of public health advocates, who hoped that the food industry could be part of the solution. In a 2008 commentary, Ludwig and Nestle(Reference Ludwig and Nestle4) observed that governments and public health organisations often ‘considered [the food industry] a stakeholder in the campaign against obesity’; and in the 2012 PLoS Medicine series on Big Food, Stuckler and Nestle(Reference Stuckler and Nestle117) noted that governments and public health advocates often supported collaborative approaches with the food industry.

However, as public health policies to reduce the consumption of sugary drinks have proliferated, enthusiasm for industry self-regulation has waned and calls for mandatory regulation have increased(Reference Buse, Tanaka and Hawkes15,Reference Paarlberg, Mozaffarian and Micha115,Reference Baker, Jones and Thow116) . Internationally, the proliferation of public health campaigns condemning the soft drink industry and the increasing frequency with which taxes on sugary drinks are proposed indicate that the soft drink industry’s political strategy to use self-regulation to pre-empt government regulation faces significant challenges. Further, the emergence of sugary drink taxes designed not only to address obesity, but to generate revenue for governments(Reference Paarlberg, Mozaffarian and Micha115), indicates that the ‘problem’ to which sugary drink taxes are the ‘solution’ is expanding and changing in scope.

As corporations continue to modify and adapt their self-regulation in response to changing market and political pressures, public health researchers need to be attentive to how and why these ‘living documents’ change(Reference Hawkes and Harris5). By analysing a data set that spans a 19-year period, the present paper provides a case study of the political motivations and consequences of corporate self-regulation. The paper also demonstrates the insights that a systematic analysis of corporate web archives can offer into how corporations have changed their responses to obesity over time.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank the journal’s editor and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. J.L.-N. was supported by a PhD scholarship from the University of Melbourne. The other authors declare that they received no additional funding to develop this paper. Conflict of interest: All authors have denied any financial or other relationship that might lead to a conflict of interest. Authorship: J.L.N. collected and analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the paper. G.S. and R.C. contributed to subsequent drafts of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.