Smoking cessation and severe mental ill health

Smoking is a key health issue for the UK population and a World Health Organization priority owing to its strong links to poor physical health, worsened mental health and conditions such as cancer and heart disease.Reference Cheeseman and Harker1 Smoking is more prevalent amongst people with severe mental ill health (SMI) and it is estimated that 57–68% of people in the UK with SMI smoke tobacco.Reference Scott and Happell2 Reducing tobacco harm in people with SMI is therefore of high importance and more focus is required to facilitate successful quit attempts.

UK primary care guidance on smoking cessation for patients with SMI suggests that they should be offered a combination of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and behavioural support, in the same way as to those in the general population.Reference Campion, Shiers, Britton, Gilbody and Bradshaw3 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance PH48 advises that all mental health trusts should be smoke-free by 2018,4 and provides recommendations on effective ways to help people stop smoking or to abstain from smoking while using or working in secondary care settings. Public Health England's subsequent guidance for mental health services on implementing smoke-free policiesReference Krishnan, Jones, Watson and Garnham5 and the Tobacco Control Plan in 20176 further cemented the importance of providing smoking cessation advice for people with SMI. Current literature primarily focuses on smoking cessation care provision for in-patient rather than community settings. Individuals with mental health conditions are currently referred to community cessation services that are available to the general public, but would likely benefit from programmes tailored to their needs.Reference Cheeseman and Harker1 The Action on Smoking and Health report recommended specific action to embed smoking cessation care in specialist mental health services.

The SCIMITAR+ trial

The Smoking Cessation Intervention for severe Mental Ill Health Trial (SCIMITAR+) (registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number database, under identifier ISRCTN72955454)Reference Peckham, Arundel, Bailey, Brownings, Fairhurst and Heron7 is the largest trial, to our knowledge, to evaluate the effectiveness of a bespoke smoking cessation intervention specifically for people with SMI, comparing regular smoking cessation provision (defined as what was available in the local area) with adapted and tailored support.Reference Peckham, Arundel, Bailey, Brownings, Fairhurst and Heron7 During the trial it became apparent that usual care varied across geographical locations and in some instances even changed. To further understand what constituted usual care in the sites taking part in the SCIMITAR+ trial, we asked the sites to complete a questionnaire describing local smoking cessation services. This paper therefore describes the existing usual care offered to people with SMI who sought smoking cessation support throughout the trial, as identified from 22 participating study sites. The aim is to better understand how smoking cessation interventions are delivered to those with an SMI diagnosis by adding to the limited information currently available.

Method

Tool

The SCIMITAR+ trial compared a mental health bespoke smoking cessation service with usual care. The survey was developed for the purposes of the SCIMITAR+ trial and provides an overview on usual care services by describing where services were provided, by whom, and how they were delivered. The survey (Appendix) comprised of eight questions, covering information on the local smoking cessation care usually provided to people with SMI.

Sample

All 22 centres that had recruited to the SCIMITAR+ trial were approached. Centres consisted of various primary and/or secondary care services in urban, suburban and rural locations across England that had significant target population sizes: Sheffield Health and Social Care Partnership National Health Service (NHS) Trust, Leeds and York Partnership NHS Trust, Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust, Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, Somerset Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, 2gether NHS Foundation Trust, Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, Rotherham Doncaster and South Humber NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust, Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust, Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, Kent and Medway NHS and Social Care Foundation Trust, Lancashire Care NHS Foundation Trust, Lincolnshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, South Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust, Solent NHS Trust, South West Yorkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Tees Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust and Vauxhall Primary Healthcare Centre.

Respondents

The research department at each SCIMITAR+ centre was initially approached in February 2017 and asked to complete the survey. Contact was made by email in the first instance, followed by a telephone call to the centre if a response was not provided within two weeks. All 22 centres completed the survey.

Research departments from each centre investigated local cessation services that acted as usual care for the SCIMITAR+ trial and provided results at an organisational level. This meant that research ethics committee and Health Research Authority approvals were not required and consent was implied. Some centres completed multiple surveys because they covered geographical areas with more than one smoking cessation commissioning; for example, Kent and Medway NHS and Social Care Partnership Trust returned one survey for Kent and one for Medway. This resulted in 28 survey responses, which are henceforth referred to as individual sites.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were produced to identify the availability of different types of services.

Results

All sites (n = 28) reported data on which organisations provide smoking cessation support in their region (Table 1). General practitioners (GPs) (n = 17) and the local council (n = 16) were the most common usual care service providers, followed by third-sector organisations (n = 15) and secondary care trusts (n = 9). However, typically these providers worked collaboratively with others to deliver smoking cessation support. It was only in three localities that the local council alone provided smoking cessation support and in two localities that GP surgeries alone provided the smoking cessation support. Third-sector organisations (voluntary and community organisations such as charities) and secondary care trusts acted as sole providers in four sites.

Table 1 Smoking cessation service provider frequency

GP, general practitioner; NHS, National Health Service.

a. Other NHS service refers to services provided by an NHS body other than a GP surgery or mental health trust.

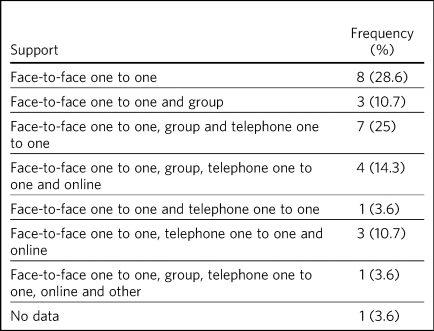

Data on the types of behavioural support available was provided in 27 sites (Table 2). One-to-one, face-to-face support was offered in all 27 responding sites. Of these, one-to-one, face-to-face support was offered in eight sites, one-to-one telephone support was also offered in 16 sites and group face-to-face support was offered in 15 sites. Online support in combination with another support type was offered in eight sites, and three or more options for behavioural support was offered in 15 sites.

Table 2 Frequency of type of support offered

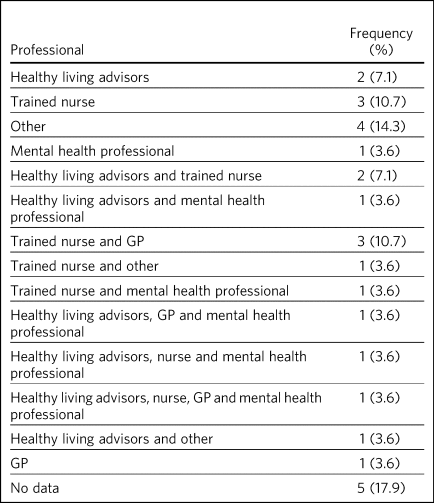

Responses on the profession of those who delivered the support was provided in 23 sites (Table 3). Multiple professions were involved in 12 sites and a single profession in seven sites. Trained nurses were the most frequent support providers (n = 12); a service delivered by nurses only and a collaboration with other professionals was available in three sites. Healthy living advisors were the second most frequent professional, reported to be available in nine sites, with seven of these instances being in collaboration with other professionals. Usual care was also delivered within sites by GP staff (n = 6), usually in collaboration with other professionals (n = 5), and by mental health staff (n = 6), also usually in conjunction with other professions (n = 5).

Table 3 Frequency of type of professional who delivers the smoking cessation support

GP, general practitioner.

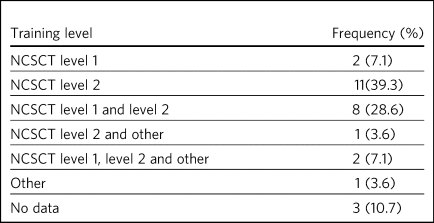

Behavioural support was offered as part of a smoking cessation service within 25 sites and no response to this item was provided within the remaining sites (n = 3) (Table 4). National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT) level 2 training was provided to practitioners in 22 sites, with 11 of those sites containing solely NCSCT level 2 practitioners, and services within ten sites were delivered by a combination of level 1 and 2 practitioners.

Table 4 Frequency of training level of practitioner who provided the behavioural support

NCSCT, National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training.

NRT provision data was supplied within 27 sites (Table 5). NRT was provided by the smoking cessation service directly in 12 sites, an NRT prescription from a GP was required in five sites and NRT was provided by both the GP and the smoking cessation service in eight sites.

Table 5 NRT provider frequency

NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; GP, general practitioner.

Finally, it was indicated that usual care changed during the course of the SCIMITAR+ trial within nine sites (6 October 2015 to 16 December 2017). Within three sites, positive changes to service availability were reported through increased training (n = 2), the secondary care trust becoming smoke-free (n = 1) and increased signposting (n = 1). Negative changes to service availability were reported within three sites. Cessation services were decommissioned within two sites, and in one of these instances, smoking cessation funding was reallocated to drug and alcohol services who would provide smoking cessation support. Within the third site, the offer of group support was ceased and further changes would occur once two local commissioners had merged. Additionally, a change in service provider during the trial was reported in two sites, with one site moving from GP surgeries to local pharmacies, and many pharmacies ceasing to provide services in the other site.

Discussion

NICE guidance advises that mental health services should become completely smoke-free, with all people who use mental health services being given full access to smoking cessation interventions.4 There is also a need for services to take into account the additional challenges that people with SMI may face when attempting to quit smoking; it is important to consider that conventional NHS smoking cessation programmes and services may not be sufficient for those with SMI.Reference Gilbody, Peckham, Man, Mitchell, Li and Becque8 However, where specialist smoking cessation services are available for people with SMI, these are generally not sufficiently evolved or embedded within the NHS.Reference Knowles, Planner, Bradshaw, Peckham, Man and Gilbody9

Principal findings

All geographical locations provided some form of smoking cessation service, but the service provider, type of service, support provider profession, smoking cessation practitioner qualifications and NRT provider varied substantially across the country and even within geographical regions. At the time of the survey in most of the sites, the smoking cessation service was provided by multiple providers.

One-to-one, face-to-face support was available in all responding regions, which was in line with NICE guidelines.4 Most sites (67.9%) also offered additional forms of support, such as group or telephone support, to offer modes of delivery tailored to patient preferences. There were also individual cases where the service providers executed their own strategies for smoking cessation. For instance, one large secondary care trust began to provide behavioural support and NRT to pre-empt the impact of enforced smoking cessation on mental health units. In this trust, all secondary care out-patients were invited to complete a care plan stating what type of NRT, if any, they would favour should they be admitted to an in-patient unit. This demonstrates a proactive approach to support patients through the smoke-free transition by taking on some service provision responsibilities.

A wide variety of professionals delivered the smoking cessation support in existing services, both between and within areas. However, our results show that it was uncommon for a mental health professional to deliver support, limiting the possibility of people with SMI receiving a service tailored to their mental health needs.

Practitioner training was somewhat standardised across regions, with staff in almost all sites having NCSCT qualifications. However, there were differences in the level of training that practitioners received. Some practitioners had only completed level one training, whereas others had attended a 2-day face-to-face training course. Although the NCSCT Smoking Cessation and Mental Health online module was available, it is not mandatory for level 1 or 2 training. Some practitioner training was provided by third-party organisations, the quality of which could not be verified.

The provision of NRT also varied across all sites, in part because of a national trend of transferring NRT provision from GPs to pharmacies or local councils, which began before data collection. Thus, in some areas GPs provided the whole cessation service (behavioural support plus NRT), whereas in others there was no GP involvement. In some sites, a prescription for NRT was required from the patient's GP despite pharmacies or local councils providing behavioural support, and in others, the GP provided the behavioural support but the prescription for NRT needed to be obtained from the pharmacy or local council.

The diversity across the various aspects of smoking treatment resulted in multiple service providers contributing to a single patient's smoking cessation care. In addition, in some centres, the provision varied depending on locality within the service area. This potential complexity of service provision is also reflected by the reported changes to a number of services during the SCIMITAR+ trial. This may be confusing for self-referring patients to understand where to access services and for staff to reliably inform patients on how to access cessation services, behavioural support and NRT. This may present a barrier to service access and a more standardised approach could be considered.

Clinical implications

The lack of uniformed pathway for smoking cessation and various local initiatives stresses the importance of local authorities to efficiently and effectively disseminate the service structure available in their region. Publicly available localised information for relevant staff to be able to signpost patients to the correct local service and for patients to self-refer to the correct local provider is therefore essential in the effort to reduce the smoking prevalence among people with SMI. In our SCIMITAR+ trial, for instance, participants in the bespoke smoking cessation intervention group fed back to the researchers that they would not have accessed smoking services without the support of a Mental Health Smoking Cessation Practitioner, who guided them through the service. This is reflected by the recent Action on Smoking and Health reportReference Cheeseman and Harker1 showing that diverse and fragmented services present a challenge to ensuring continuity of care across different parts of the healthcare system for people with a mental health condition who access cessation services. Substantial efforts are therefore required to improve referral pathways to services to make it easier to people with SMI to access relevant support. Signposting to relevant services could be improved by increasing use of the NHS Smokefree Local Stop Smoking Services website that details smoking cessation services by location (www.nhs.uk/smokefree/help-and-advice/local-support-services-helplines).Reference Knowles, Planner, Bradshaw, Peckham, Man and Gilbody9,Reference Bradshaw, Davies, Stronach and Richardson10

The absence of consistent provision of NRT might not in itself be a barrier to service access. However, if a patient has to visit multiple locations to receive both behavioural support and NRT, it might become an extra burden and discourage them from utilising the full services available, which could reduce the effectiveness of the service. Furthermore, in the case of separate provision of behavioural support and NRT, the lack of communication between the two providers might become a barrier to realise the full effectiveness of the services.

Study strengths and limitations

The present survey was a useful tool to describe usual care and summarise key service components. It successfully captures differences between and within the surveyed regions and has helped to point out the potential challenges to smoking cessation service provision for those with SMI. The survey was particularly effective at highlighting and quantifying the complexity of smoking cessation services in participating sites in England. The study does not evaluate the effectiveness of usual care services. This paper provides a description of services and gives an indication of service accessibility throughout the UK; however, the survey was not designed to evaluate accessibility nor measure the numbers of referrals made, service uptake or service success. These factors, which would provide clearer evidence for or against some forms of provision, warrant further exploration.

It is not clear whether multiple service providers operating in one area improves access by making services more available or whether this makes it more challenging to identify the correct referral pathway for both individuals and clinicians. For sites that reported multiple service or NRT providers, it was not clarified whether single or multiple options were available to patients; for example, pharmacies may issue NRT in one area and local councils may issue it in another.

Sites were not clearly instructed under what circumstances they should complete multiple surveys (for example, for separate areas within the Trust) and this lack of clarity may have led to unreliable data. Additionally, the present survey was completed by research staff and not by those embedded in clinical teams, which may reduce the reliability and validity of the data. Although some research staff reported that they consulted those within clinical teams for information when they could not find it themselves.

All participating sites recruited patients to the SCIMITAR+ study and hence were interested in smoking research. This could increase sample bias as these sites have demonstrated value in improving smoking cessation services and therefore may have more developed services than non-participating areas. Use of a wider sampling method and sampling clinical teams and patients would collect more in-depth data, increase generalisability and improve evaluation of NICE compliance on a national scale.

Future research

Further research could involve a random sample of patient-facing NHS staff being asked how they refer patients who seek smoking cessation support, to ascertain knowledge of service availability and referral pathways. In addition, patients who smoke could be surveyed to collect information on whether they have been referred to cessation services, whether they are aware of the services available to them and how they would access those services. This would provide additional information on how NICE guidelines are being implemented and how easy it is for NHS staff to implement the guidance.

About the authors

Paul Heron is a research fellow in the Mental Health and Addiction Research Group at University of York, UK. Tayla McCloud is a PhD student in the Division of Psychiatry at University College London, UK. Catherine Arundel is a research fellow at York Trials Unit, University of York, UK. Della Bailey is a research fellow in the Mental Health and Addiction Research Group at University of York, UK. Suzy Ker is a consultant psychiatrist at Huntington House Mental Health Resource Centre, Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Jinshuo Li is a research fellow in the Mental Health and Addiction Research Group at University of York, UK. Masuma Mishu is a research fellow in the Mental Health and Addiction Research Group at University of York, UK. David Osborn is Professor of Psychiatric Epidemiology in the Division of Psychiatry at University College London, UK and is a consultant psychiatrist in Research and Development at Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Steve Parrott is a reader in Health Economics in the Mental Health and Addiction Research Group at University of York, UK. Emily Peckham is a research fellow in the Mental Health and Addiction Research Group at University of York, UK. Alison Stribling is a research practitioner at the Windsor Research Unit, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Simon Gilbody is a professor and the director of the Mental Health and Addiction Research Group at University of York, UK.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Programme (project number 11/136/52). S.G. was funded by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Yorkshire and Humber. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, the NIHR, or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. D.O. is supported by the University College London Hospitals NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, and he was also in part supported by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care, North Thames at Bart's Health National Health Service Trust.

Appendix. Details of usual care form

Site name:________________________________________________

At the current time, who provides Stop Smoking Services in your area?

Local council □

GP surgery □

Secondary care trust □

Other NHS please state □

Not-for-profit company □

Charity □

Other third-sector organisation, please state______________

How is this support delivered? (Select all which apply)

One-to-one face to face □

One-to-one over the phone □

In a group □

Online support □

Other, please state __________________________

Does this service offer a choice of how the support is delivered?

Yes □ No □

Does this service provide behavioural support?

Yes □ No □

Who provides the behavioural support?

Trained nurse □

Healthy living advisor □

GP □

Mental health professional □

Other, please state ________________________________________

If the service provides behavioural support what level is the person providing the support trained to?

NCSCT level 1 □

NCSCT level 2 □

Other training, please state ________________________________

How does a person accessing the service receive NRT?

NRT provided by the service □

Service requests the GP to prescribe □

NRT not available □

Other, please state_________________________________________

Has usual care changed over the course of SCIMITAR+?

Yes □ No □

If yes, please state briefly how it has changed including details of how usual care was originally delivered at the start of the study:

___________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.