Introduction

In August of 2016, I participated in a shūkatsu-tsuā (end-of-life preparation tour), organized by the Nagano Elderly Cooperative (長野県高齢者協同組合), a voluntary non-profit organization (NPO) established by the Nagano elderly in 1996. About 20 of us took a bus ride to a tree burial ground (樹木葬) run by a Buddhist temple (see Figure 1). A tree burial is a form of natural burial that involves planting a tree in a good location and burying the ashes of the deceased at its roots. We listened to a monk explain the background of the natural burial ground: its history, budget, and operating system. After his talk, the elderly toured the natural burial ground, with some even scouting for a plot where they imagined they might be buried one day. Accordingly, this shūkatsu-tsuā (終活ツアー) provided the elderly with an opportunity to reflect on their own deaths, primarily on the issue of how they would dispose of their bodily remains.

Figure 1. Shūkatsu-tsuā to carry out a natural funeral. Source: Photo by the author.

The Nagano Elderly Cooperative has held the classes for local seniors in which I participated as a researcher from the early 2000s. Topics of interest include meals and exercise, nutrition and safety, combating arteriosclerosis and cognitive decline, finding a healthy balance between the body and brain, and volunteer opportunities in the local community. The elderly could participate in all the classes for a fee of ¥500. In 2010, with the rising trend among elderly people of preparing for one's own demise through various practices, a new topic emerged on the shūkatsu (終活) programmes, including the writing of an ‘ending note (エンディングノート)’. The purpose of an ending note is for someone, in preparation for the end of their lives, to leave notes about memories of their lives, wishes regarding their funerals, and messages to their loved ones.

Shūkatsu programmes, including the writing of ending notes, have been introduced by NPOs and local associations for the elderly in Nagano and other prefectures. Buddhist temples, meanwhile, have introduced one-day trips called shūkatsu-tsuā to burial grounds that offer so-called ‘natural funerals’. In 2009, Asahi Weekly even included a report on planning your funeral, including choosing your attire and disposing of your estate. In 2010, with shūkatsu becoming a popular neologism, businesses and trust banks began sponsoring exhibitions of products and services related to this fast-growing trend. In 2018, the sales value of death preparation businesses in Japan was estimated at approximately ¥1.84 billion, an increase from around ¥1.76 billion in 2014.Footnote 1

The ending note is one of the most accessible forms of shūkatsu for the elderly. Both elderly cooperatives and local governments began distributing their own ending notes for the local elderly population to complete, as part of a broader programme of classes and workshops on ending notes. Compared to a will, which directs the disposal of one's property and estate, an ending note is much more comprehensive. It contains specific instructions for a wide range of matters following one's death, including the disposal of assets; notifying family, friends, and next-of-kin; and funeral arrangements. Among the instructions for the funeral arrangements are details about the deceased's preference for either burial or cremation, coffin for the body or urn for the ashes, and their choice of music, photos, and decorations for the funeral service. More recently, the content of ending notes has expanded to include directives about life-prolonging treatments, should their authors become terminally ill.

The 2011 documentary ‘Death of a Japanese Salesman (エンディングノート)’ by Sunada Mami sparked much public interest. It chronicles the life of Sunada Tokoaki, the director's father, who worked as a ‘salaryman’ for over 40 years before being diagnosed with stage five stomach cancer. His diagnosis came just before his retirement. Despite this cruel twist of fate, Mr Tokoaki does not display fear, anger, or resentment. Instead, always a meticulous person, he spends his remaining days writing an ending note in which he leaves instructions for his funeral arrangements and guest list, and the execution of his will. After receiving rave reviews, this documentary, which initially opened in only two cinemas, went on to be shown at more cinemas across the country, eventually reaching an audience of over 200,000 people. With the popularity of the documentary, a national trend of ending notes began, especially among celebrities.

Building on this popular interest, there has been growing academic interest in the topic of death.Footnote 2 Research examining the attitudes and preparations for death among Japanese people has appeared in the fields of nursing, medicine, and gerontology. However, these studies have ignored the larger question of why the interest in death is steadily rising among the elderly. Similarly, an analysis of why so much interest, capital, knowledge, and discourse are being invested in the activity of preparing for one's death has also been lacking. Nor has there been sufficient focus on how this emerging discourse around preparing for one's death is transforming the lifestyles of the elderly.

Reflecting on the trend of end-of-life preparations in Japan, this article seeks to examine how the elderly think of such preparations and the types of dilemmas they face as they undertake these activities. In this way, this article explores why the elderly, who are the subject of this phenomenon, feel pressured to prepare for their own deaths. Further, I investigate how the emergence of new rituals in which the elderly are both imagining and preparing for their own deaths can be connected to larger sociocultural changes. This article is based on two years of intensive fieldwork from 2009 to 2011 in the city of Saku within the Nagano prefecture, with follow-up visits from 2013 to 2019. All the interviews, which were originally conducted in Japanese, and archival material were translated by myself. All interviewees have been given pseudonyms.

The changing trend of preparing for one's death in contemporary Japan

The Nagano prefecture where I conducted my research was once infamous for the practice of ubasute, in which elderly were left to die in the mountains once they turned 60.Footnote 3 In the postwar period, this region also had the country's shortest life span. With Nagano prefecture being far from the sea and 73 per cent of its landmass covered by forests, its residents had difficulty acquiring protein in their diet through meat or fish. Moreover, with its long and harsh winters and poor transportation infrastructure, the population relied on salt to preserve their food. This diet contributed to the highest mortality rate in the nation, resulting from cerebral vascular diseases, such as strokes.

From the 1960s, civil servants in the region, including medical staff, have aggressively waged public campaigns to reduce the amount of sodium in the residents’ diets. Moreover, they have introduced a variety of programmes, including medical check-ups and ‘health diaries’, to raise awareness of illness-related issues among local residents, who might otherwise only visit a hospital just prior to their death. As a result of these efforts, after the 1990s, the average life span of the elderly in Nagano prefecture became the longest in the country. Their employment rate showed a corresponding increase to also become the nation's highest. Additionally, the region still has the country's lowest expenditure on medical expenses and the shortest period of hospital stays for the elderly. Even so, few elderly people live past 100 years of age.Footnote 4 Given Saku's reputation as a ‘healthy city of longevity’ from the 1990s, where many elderly people live pinpin (healthily) and die korori (promptly), it served as a suitable setting for this study on dying in Japan.Footnote 5

The case study of Saku seems to be well explained by the notion of Michel Foucault's ‘biopolitics’. According to Foucault, with the onset of capitalist modernity, the mode of governance also began to change. The ultimate display of a sovereign's power to kill within the ancient regime began to be displaced by the imperative to cultivate the energies of the living as part of the calculated management of life within modernity.Footnote 6 Thus, what is happening in Saku was due to the transformation of the sovereign power that used to leave the elderly over the age of 60 to die in the mountains to a biopower that undertook diverse welfare policies to help the elderly achieve more pinpin korori.

However, as many scholars note, it is clear that Foucault's claim did not reflect sufficiently on how the emergence of biopower, whose highest function was no longer to kill but to invest in life, would provoke new forms of anxiety and disquiet.Footnote 7 For example, as anthropologist Amy Borovoy notes, the Japanese public health paradigm has explicitly linked health to broader social norms and cultural values. ‘Health’ is not a medical condition but a statement of beliefs, identity, and even national values. Intensive regimes of socialization have aimed to shape behaviour and subjectivity according to the public health paradigm in Japan since the late nineteenth century.Footnote 8 Yet, Borovoy explains how such a public health paradigm has come to emphasize self-responsibility for health in the transition to neoliberalism over the past few decades. Whether it is a health check-up programme that emphasizes a regular assessment of one's diet or the discourses that encourage the elderly to prepare for their own deaths, both create self-regulating neoliberal subjects. Consequently, the policymakers and medical teams make no mention of structural conditions leading to obesity, chronic illnesses, or involuntary retirement. Instead, they only emphasize individual responsibility. As such, there is a need to unpack the contradictory impact of government actions that aim to create comfortable lives for citizens, yet which give rise to new forms of anxiety, uncertainty, and even desperation.Footnote 9

Moreover, in contrast to what Foucault pointed out, the Japanese elderly have not turned away from death as a taboo topic, even within the regime of the biopower.Footnote 10 Rather, in contemporary Japanese society, death is a topic that is actively discussed. Also increasing is the number of elderly who are actively planning their own funerals. According to anthropologist Hikaru Suzuki,Footnote 11 similar to ‘the Revival of Death’ movement in the Western world discussed by Tony Walter, a new approach to death is exerting authority over how one is to die in Japan; that is, the deceased-to-be are physically and psychologically becoming ensnared in the drama of their own process of dying. As members of a ‘scattering ashes’ society or by purchasing a plot of land for a tree burial,Footnote 12 many are becoming not only the lead actors but also the directors of their own deaths. From a passive role where they were taken care of by others, the Japanese deceased-to-be are shifting to the active position of orchestrating their own dying.

The growing trend in Japanese society to methodically prepare for one's death while one is still healthy can be attributed to expanding forms of neoliberal governmentality. Within such a society, the individual is expected to manage themselves like a corporation. Following the practices of shūkatsu (就活, activities planning for employment) and konkatsu (婚活, activities planning for marriage), shūkatsu (終活, activities planning for one's death) simply becomes another arena for the self-management of one's life at a particular stage of that life.Footnote 13

This article examines the neoliberal biopolitics of ending notes by focusing on how preparing for one's death has become another facet of neoliberal self-management. Additionally, by critically examining the dilemmas experienced by the elderly as they go about meeting the social expectation that they will plan their own deaths, the article also aims to illuminate the unfolding politics of life in an East Asian context, which is rapidly transforming from an ageing society to a tashi shakai (多死社会, mass dying society). Indeed, as the Japanese elderly are increasingly pressured to reduce the meaning of dying to the material disposal of their bodily remains, they also struggle to re-secure death within the social and ethical realm of the living.

In order to accomplish these objectives, this article first investigates the expansion of a Japanese-style neoliberal welfare system, which is responsible for new anxieties among the elderly. Second, it explores the ways in which the new social pressures on the elderly to prepare for their own deaths are part of neoliberal life politics. Finally, this article discusses the dilemmas experienced by the elderly as they prepare for their deaths and the struggles they face as they refuse to reduce death to the disposal of their material remains.

The emergence of the Japanese neoliberal welfare regime and the increasing anxiety of old age

This section explores how the progression of the Japanese government's neoliberal welfare regime, which speaks of a socialization of care but still relies on the family and emphasizes individual responsibility, gives rise to new forms of anxiety among the elderly. Such anxieties centre, in particular, around the need to avoid a social death associated with dementia and other illnesses requiring the care of others. An entire system of managing ageing as a sign of dying has been built around this particular population. To understand such a neoliberal elderly health management system, it is necessary to examine how this concept of public health and hygiene was established in the historical context of Japan.

Since the invention of the Japanese public health regime in the nineteenth century, the primary health concerns of the Japanese government have shifted from sanitation and the control of epidemic diseases, such as smallpox, cholera, and typhoid, to the management of chronic conditions. The concept of eisei (‘hygiene’) was introduced by Nakayo Sensaie (1838–1902). As a member of the Iwakura delegation to the United States and Europe between 1871 and 1873 sent to learn about American and European civilizations, Nakayo first discovered the German concept of ‘public health’ (gesundheitspflege). As a pioneer of Western medicine in Japan since 1874, he soon familiarized himself with governmental techniques to ensure the health of citizens. Alongside the translation of the concept of ‘health’ to ‘hygiene’, the connotation of an active government intervention remained. In China, weisheng, which is now rendered into various English terms such as ‘hygiene’, ‘sanitary’, ‘health’, or ‘public health’, was associated with a variety of regimens of diet, meditation, and self-medication that were practised by the individual before the nineteenth century to guard fragile internal vitalities.Footnote 14 In both Japan and China, centralized government intervention became important for the provision of new social services through a large-scale public health infrastructure, such as the sewer system, which enabled the quarantine, surveillance, and vaccination of the population.Footnote 15

With the transition from an era of infectious diseases to an era of chronic diseases, public health introduced different interventions that focused increasingly on the modification of individual behaviour (that is, personal avoidance of risk) and daily practices to avoid infection. Meanwhile, the turn towards managing different aspects of lifestyles, such as exercise, diet, alcohol consumption, and sexual behaviour, raised questions about the appropriate purview of government and medical intervention. In turn, the newer concept of ‘population health’ (kenkō zōshin), which sought to extend public health activities to housing, income, and infrastructure, reflected these wider concerns.Footnote 16

This broad history of public health in Japan is also reflected in the creation of a medical welfare system to oversee the elderly population. The Japanese Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) was revised in 2005 to strengthen both preventive and community-centred programmes for the elderly. Such reforms were closely tied to the Japanese government's efforts to restrict the number of LTCI recipients. Claiming welfare abuse by the elderly, the government tried to rein in public expenditure on elderly care. With such reforms, it became the primary responsibility of civil servants and medical professionals to supervise the elderly. Government-run classes, in particular, became a major site for elderly recipients of LTCI to learn body- and health-management techniques.

According to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the estimated prevalence of dementia among people aged 65 and over increased from 681.9 per 100,000 people in 1999 to 2,029.5 per 100,000 people in 2014.Footnote 17 As the number of elderly people with dementia increased, the government tried to prevent the elderly from transitioning to the stage when they would need care. Nevertheless, the number of elderly people with dementia has increased from 1.49 million in 2000 to 4.6 million in 2018. With this increase, care has become a pressing social issue. Families who have trouble taking care of their elderly with dementia opt for nursing facilities where the elderly can stay indefinitely. In the case of elderly people with middle or late dementia, many lack the necessary level of care at home and need to enter specialist nursing homes.

Nevertheless, in Saku, as of March 2010, there were about 736 elderly on a waiting list for these specialist nursing homes which means that the number of people wishing to enter a nursing home was far greater than the number of available nursing home places. For this reason, only those with very poor health are able to make use of these facilities. In particular, in the case of specialist nursing homes operated with subsidies from the local government, increasing the number of places at these facilities would inevitably lead to an increase in the tax burden. Therefore, local governments actively controlled the number of specialist nursing homes.

Responding to this gap in elderly care, the Japanese government announced the expansion of ‘Shōkibo Takinō Shisetsu (small-scale multi-functional facilities)’ to support the care of elderly people with dementia living ‘within their own regions’. Following this announcement, one such facility was established in Saku. When I visited it in 2010 as a volunteer worker, I heard many complaints from the staff about their heavy workload. They declared that they were doing the same amount of work as those employed in a ‘large-scale multi-functional facility’. The staff of small-scale multi-functional facilities undertake intensive care for the elderly with dementia who live alone. This is done by visiting those they are contracted to care for, or whose families make such requests, once an hour at their homes to check in on them or to help them take medicines at the right time, and so on.

In 2010 on one such visit the care staff and I knocked on the door of Mr Yodashi, who was around 80 years old. When there was no answer, one social worker reached into her bag to take out a house key. When we stepped inside, the house was quiet and cold with no heating on. Opening the bedroom door, we saw Mr Yodashi sitting by himself quietly in a corner, with a vacant stare. All of his hair had fallen out. His head drooping, Mr Yodashi seemed to be unable to hear or see anything in front of him. Even though he displayed all the symptoms of dementia, his evaluation at ‘moderate’ meant that he was not yet eligible to be moved into a nursing home. When a care worker tried to engage him in conversation, he did not reply. We had no other choice but to step out of the house and lock the door, leaving him alone in his bedroom.

As seen in the case of Mr Yodashi, these small-scale multi-functional facilities do not necessarily help the elderly with ‘self-sustained living’. Rather, they facilitate the elderly who should not be living alone to remain in their homes. The regular visits mean that they will not be left dead for a lengthy time, thus preventing a kodokushi (lonely death). As mentioned above, some elderly with dementia live with their families or under the supervision of facility staff, but some are initially denied admission to a multi-functional facility if they are violent or have a habit of wandering. Only when their condition worsens or they are abandoned even by their families, do they become eligible to enter the facility.

In Japan, concerns over dementia overlap with those over the related but separate medical category of ‘boke (senility)’.Footnote 18 In contrast to ninchishō (認知症, dementia), many elderly feel that senility is something they can prevent through an active lifestyle. As such, they feel a strong obligation to avoid this condition through their own efforts. This pressure to maintain one's health and not be a burden on society is felt especially by the elderly who feel under threat of dementia.

Within Japan's welfare system for the elderly, which emphasizes reciprocity between individuals and society, the mere effort of the elderly to maintain their health is interpreted as a contribution to society. In contrast, becoming senile means that one is a self-centred and anti-social being, who is a burden to the society.Footnote 19 Accordingly, the elderly express a deep fear of getting dementia when they would be considered physically alive but socially dead. In my interviews with the elderly in the Saku area, this fear of becoming a social burden was made evident in the frequent mentions of how they would prefer to die from a heart attack or cancer than suffer from dementia. Many spoke from personal experiences as they had observed the heavy burden of care imposed upon families when an elderly person suffered from dementia.

As the neoliberal welfare system progresses, the fear of ageing and of becoming a burden to society is amplified. Even though the Japanese government has relied upon state-administered services to create a society of care, it has now reached a point where it has chosen to reduce the public demand for these services. In this context, the responsibility for taking care of the elderly who are susceptible to dementia has shifted from the state to the individuals themselves. Fearing the social burden associated with boke or ninchishō, the elderly are unrealistically pressured to lead healthy lives. In this manner, the promotion of the elderly population's well-being is inseparable from the government's efforts to prevent ‘bad deaths’.

Daily rehearsal of death

In the past, a ‘bad death’ in Japanese society referred to a case where one did not become an ancestor after one's biological death. In order to transition successfully to the ancestral world, the deceased needs to become the object of kuyō (ongoing rites of respect) by their living descendants.Footnote 20 Without someone to conduct the rites of respect, the deceased is unable to maintain the status of hotoke-sama (‘Buddha’) but becomes a muenbotoke (‘spirit without ties or wandering ghost’) within the ancestral world.Footnote 21 Put another way, a ‘good death’ in Japan requires one's body to be treated as ‘honourable remains’ by one's descendants. Neglecting one's attachment to one's ancestors is a failure to acknowledge the fundamental, interdependent relationship between the dead and the living.Footnote 22

It is important to note that as the neoliberal framework emphasizing the individual's responsibility became more established, the meaning of ‘bad death’ is transforming to refer to the death of a person who has not prepared for it appropriately. It is in this context that the interest in writing ending notes has increased. In 2011, the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry started a research group composed of 11 experts (including a lawyer, a funeral director, a representative of a consumer organization, and a journalist) to make recommendations on how the elderly should prepare for their deaths. Such initiatives not only challenge the social taboo surrounding death, they also create consumers who are ‘conscious of their own dying’. In one so-called ‘Ending Expo’, models of ‘rubbish houses’, including one of an abandoned elderly person, were put on display. By disclosing the unseemly consequences of an unplanned death, they encouraged the elderly to become consumers of their own death preparations.

Among the items associated with death preparation are: sorting out one's affairs, arranging hospice care, making funeral and burial plans, executing a will and working out issues of inheritance, and record keeping. Within the discursive structure calling for end-of-life preparations, one is expected to prepare for one's social death even prior to one's biological death. From the perspective of advocates of end-of-life preparations, ‘if one were to meet some misfortune before having expressed one's wishes in an ending note’, then it is already too late.Footnote 23

With the fraying of family ties and knowledge, ‘preparing for death in advance’ is becoming increasingly important. When parents die, children do not know whom to notify nor how to carry out the funeral rites as few have the necessary knowledge or the will to engage. These days, thanks to their pensions, the older generation enjoys a certain degree of financial stability. Facing a more uncertain future, the younger generation often lack the means to buy burial plots or carry out ancestral rites for their parents.Footnote 24 Even if they have the money, they are not expected by their parents to carry such costs.Footnote 25

In fact, the number of burial plots with interrupted ancestral veneration is steadily growing. Some become neglected when a family lacks descendants to take care of them. Others are left untended when family relations become distant.Footnote 26 In the Saku region, hakamairi (‘annual visit to one's ancestral graves’) opens on 1 August of every year. During this event, local residents not only look after their own family's burial plots but also those of their neighbours with no children.Footnote 27 The elderly feel that it is too burdensome, however, to ask their children to take care of the burial plots of both their direct and distant ancestors. Recently in Japan, the term hakajimai (墓じまい) has emerged which refers to the act of removing the tombstone and moving the ashes of the deceased to another burial site. Mmuyen-bochi (無縁墓) refers to the grave sites of those without relatives that are, thereby, left neglected without hakajimai. In Figure 2, once can see the steadily increasing number of grave sites in Saku area that have fallen into neglect.

Figure 2. Neglected grave sites in Saku area. Source: Photo by the author.

Aware of this trend, many elderly people I spoke to felt pressured to pay a funeral home or a Buddhist temple to prepare a burial plot for themselves and their children while they are still alive. As mentioned above, tours to grave sites, where the elderly can directly examine how they operate, are also popular. During such tours, the elderly without children can attend to various details, including their choice of tombstones, the words to be etched on them, and the contract period for the care of their graves. With the funeral plots already allocated, the only thing missing on the contract is the date on which they will be buried.

The ending note not only facilitates the elderly in deciding how to prepare for their funerals, but also how to end their social relationships with their peers. With fewer members of the younger generation willing or able to carry out the funeral rites, many elderly people in Saku refrain from attending a wake to pay their condolences when their friends pass away. If they attend the wake and help out, they are afraid that their friend's children will feel obligated to do the same when they themselves pass away. Accordingly, some make a request in their ending note not to receive the assistance of others when they die. The act of not participating in a funeral rite can be interpreted as ending the relationships one had in life with one's own generation. This carries significance in terms of redefining the meaning of the funeral.

Given that children often do not know how to carry out their parents’ funerals, many local governments, including Saku city, work hard to ensure that their elderly residents complete their ending notes before their deaths. A civic association in the Nagano prefecture also encourages its elderly residents to prepare for their deaths by supplying them with templates for their ending notes. In this way, writing an ending note is not simply a way to avoid becoming a muenbotoke (無縁仏, ‘spirit without ties or wandering ghost’). Rather, the reason why ending notes or preparations for death are so emphasized is not just to give instructions for one's funeral, but because of the pressure to put in order all the material remnants of one's life.

As seen above, ending notes are at the heart of shūkatsu activities that mandate one to deal with the contingencies around one's death ahead of time. In commercially available ending notes, the need to make arrangements for all contingencies, including dementia, is strongly emphasized. So is the need to prepare for the possibility of hospice care for an elderly patient who is bedridden, suffering from dementia, or both. Indeed, many of the questions relating to death preparation involve the issue of care. If an elderly patient is showing signs of cognitive or physical decline, to what extent should the doctors seek the diagnosis of the disease and treat them? What about life-prolonging treatments? Should they be pursued in the case of a terminal illness? How about assisted suicide? Has a form allowing for such contingency been completed, or the forms allowing the elderly patient to donate—or receive—a vital organ? And, finally, should one leave behind one's cadaver for scientific research?Footnote 28

The pressure to make arrangements for all contingencies around end-of-life care is also extended to funeral and burial arrangements. The ending notes are replete with questions relating to one's preferences for different aspects of the funeral service. For instance, should a funeral service be held? Has the name, contact number, and religion of the person to preside over the funeral service been confirmed? Have the reservations for the funeral parlour been made and funds to rent it been set aside? Is there a need for an altar? If so, should it be an ordinary or Buddhist altar? And how should it be decorated? With what type of flower arrangements?Footnote 29

The questions relating to the funeral service do not stop there but extend to the choice of coffins. Does the deceased-to-be prefer a plain coffin or one that is ornately decorated? The same goes for the funeral urn. If its use has been designated, does the elderly person prefer a white one or something more colourful? How about the vehicle to transport the hearse? Is an ordinary bus or a limousine preferred? If a car, does it matter that it is locally manufactured or does it have to an imported brand?Footnote 30

As such, the ending note mainly consists of questions for the elderly person on how to deal with their material remains, rather than presenting them with an opportunity to reflect on death as an existential transformation. This shows that the concept of funeral rites, which had previously performed the function of ending the grip of the deceased on the living in both symbolic and social ways,Footnote 31 is changing. Furthermore, as Philippe Ariès notes, the significance of drafting one's will, which at the beginning of the eighteenth century had served the religious function of allowing one to confess one's sins and profess one's faith before dying, is also changing.Footnote 32 Death within the context of end-of-life preparations for contemporary Japanese elderly resembles more of a shopping list of tasks to be completed. Under the previous interpretations of tsui (終, ‘the end’), the elderly focused on the broader existential questions of whether they had completed all their duties and responsibilities.Footnote 33 In ending notes, they are confronted with more material considerations, including whether they have properly disposed of their material remains following their biological death.

Through ending notes, the elderly person is required to create a ‘post-self’,Footnote 34 a person who is concerned about maintaining their reputation and image even after death. Such a post-self bears a strong resemblance to the enterprising self of neoliberalism, which seeks to calculate and better manage their assets in order to improve themselves.Footnote 35 Indeed, the ending notes produced by the shūkatsu business include countless questions that encourage the elderly to monitor themselves in order to create their post-selves. Within the discourse of the shūkatsu business, if a post-self lacks the rational capacity to govern itself, under the influence of dementia or life-prolonging treatments, then that post-self must be rejected.

Dilemmas of shūkatsu and the ethics of dying

When one applies the perspective of anthropologist Robert Hertz, who did not see death as a one-time event, but rather a period of transition in which the deceased moves from the realm of the living to the realm of the dead as a venerated ancestor, the post-self must inevitably be built on the support of those who remain alive. However, with the emphasis of the neoliberal stance stating the elderly must prepare for their own deaths, the elderly are also under pressure to prepare their own post-selves as well. The following three cases illustrate both the everyday preparations and ordinary dilemmas confronted by the elderly as they imagine their own deaths and their family members after their deaths.

Mrs Waku's case

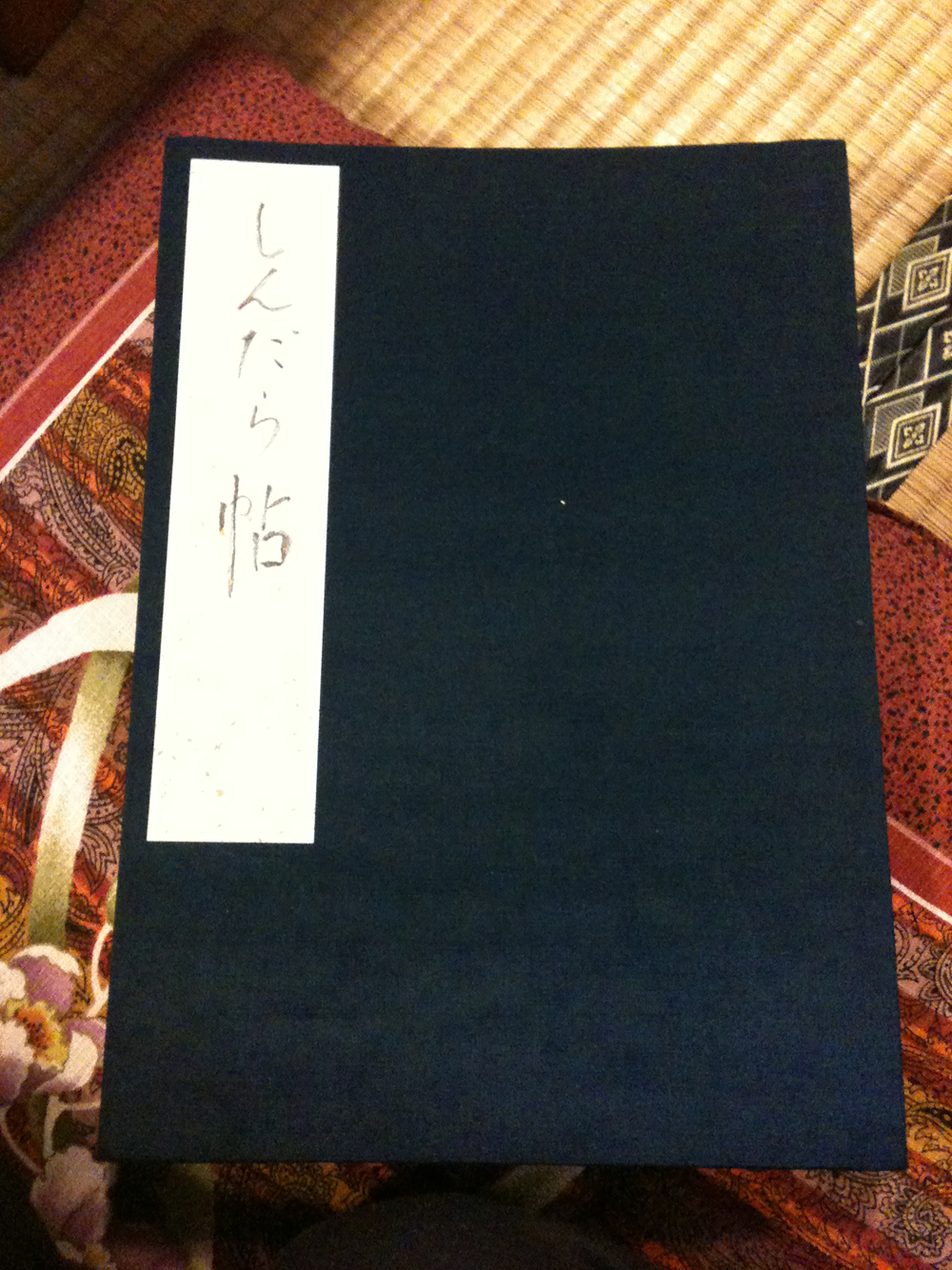

Mrs Waku, who turned 90 in 2019, started writing her ending notes at the age of 74 (see Figure 3). What motivated her to write them was the death of her husband from cancer and the funerals of several of her friends. More than anything, however, she was encouraged by a friend, Mrs Sunohara. A writer just like Mrs Waku, Mrs Sunohara gathered her friends and family members to hold an exhibition of her life and work as a memorial while she was still healthy. A month after tripping and falling in her home, Mrs Sunohara even completed the legal step of bequeathing her entire estate to her daughter-in-law, with whom she was on especially good terms. Upon observing Mrs Sunohara's preparations, Mrs Waku also came to realize that she did not know what would happen when she passed away. So she started creating an ending note with the title ‘Book for when I die’, ‘Sindara Chou (しんだら 帳)’. In the ending notes available at bookshops or provided by various local government or non-profit organizations, there are a number of common questions regarding the information needed to deal with one's material remains after one's deaths. As opposed to these ending notes, Mrs Waku prepared a notebook in which she wrote down her thoughts and requests regarding her death, and where she included messages for her loved ones.

Please don't put me on a life prolonging treatment. If I were to be put on life support via a feeding tube, then living everyday would be torture. I won't say anything so obvious as that I want to die in my own home. If you do take me to the hospital, just make sure, once again, that I am not put on a life-prolonging treatment. Passing away naturally in my own bed at home would be best. Can you understand where I'm coming from? I'm not saying that staying at home is always better than dying the hospital. I will let you make the decision as the situation unfolds. (15 October 2002)

Figure 3. Mrs Waku's ending note. Source: Photo by the author.

On that same day, Mrs Waku wrote specific instructions on how she wished to be treated when she was on her deathbed, and included a number of documents. First of all, she wished to avoid all types of life-prolonging treatments. Instead, she wished to die with dignity. She also wished to donate her body to medical research. Later, however, when she told her family doctor that she had written such a note, he replied that her instruction ‘I wish to refuse life-prolonging treatments’ was too general. In response, on 29 August 2007, Ms Waku added more sentences explicitly refusing the intake of fluids via an IV tube or food through a feeding tube. She later wrote,

I know that if I don't leave these explicit instructions, the doctor may be put in a difficult situation when the time comes: I don't wish for a feeding tube nor a respirator. I'm fine without an IV tube for fluids as well. If I can no longer eat nor drink, that will simply be the end [of my life]. And I'm happy with that. (29 August 2007)

In addition to instructions for hospice care, Mrs Waku also left instructions for her funeral. She put,

I would like a farewell party at home, not a funeral. I do not need an incense altar nor a guestbook. However, please do display the books that I wrote or edited, as well as the records and cassettes of my poems. These are my ‘life evidences’ as a person. Meanwhile, at the farewell party, I would prefer my favorite melody and the ringtone on my phone, ‘Longing’, to be played in the background.

Mrs Waku's left specific instructions for a farewell party that would be more a commemoration of her life and her work than a funeral. To ensure that the farewell party was exactly as she imagined it to be, she left instructions not only for the choice of flowers but also for the photos of herself that would be displayed. She even designated a family heirloom—a ceramic piece that she had used as candy jar—to hold her ashes after the cremation. Mrs Waku was not refusing traditional funeral rites per se, but she wanted the party to reflect her life philosophy rather than be a superficial and rushed ritual. As a result, Mrs Waku's ending note did not contain all the information that was usually recommended in the shūkatsu business, nor was it as detailed as recommended by end-of-life preparation experts.

Indeed, as Mrs Waku wrote her ending note, she found it difficult to separate her future deceased self from the person that she had been. In trying to describe the manner in which she wanted to die, she had no choice but to look back on the values that had guided her entire life. In other words, rather than existing as discrete moments separated by time, life and death became integrated in her life as one continuous stream. Her efforts to integrate her future self, which was dependent and overwhelmed by symptoms of dying, into her present self, guided by certain values, thus challenged the self in the end-of-life preparation discourses. These practices of Mrs Waku were different from the end-of-life preparation discourse that rejects the self who lacks rational capacity.

Moreover, as Mrs Waku kept writing her ending note over the course of 15 years, she began to encounter more dilemmas. For one thing, she kept changing her mind about certain matters. Initially, she had asked to be buried in her Western-style wedding dress. For her traditional Japanese wedding, Mrs Waku had not been able to wear a Western-style wedding dress. However, she really wanted one before she died, so she bought one with her son's first pay cheque. Later, however, thinking about the discomfort of lying in a narrow casket during her farewell party, before she would be cremated, she changed her mind and asked to be put in a simpler dress.

Mrs Waku's dilemmas as to the contents of her ending note were no more apparent than in her choice of people to tend to her death. Initially, Mrs Waku had left a heartfelt message for her daughter-in-law, Mrs Natsue:

Mrs Natsue, just like your name, you have always treated me gently. Not only am I grateful for the grandchildren that you have given me, I am also thankful for the kindness that you have always extended me.

However, ten years later, things were different. Her son had remarried, giving Mrs Waku a new daughter-in-law. This change, in turn, left Mrs Waku with no choice but to designate a new beneficiary to her estate. Similarly, the list of guests invited to her farewell party changed as friends moved on or they themselves passed away. Mrs Waku had a close friend in a friend of her own son. She had invited him to visit her burial site when she passed away and share a drink. However, when this friend passed away before her in a car accident, she had to delete this request from her ending note.

By March of 2012, Mrs Waku was referring to the ending note that she had crafted with instructions for her end-of-life care and funeral service as perhaps nothing more than her ‘impetuous thoughts’. Moreover, she expressed her hope that her funeral service would ‘minimally’ express her wishes. After witnessing the untimely deaths of hundreds of people following the earthquake and tsunami in northeastern Japan in March 2011, Mrs Waku felt the meaninglessness of preparing for death even more keenly:

I'm sorry but after the giant earthquake on March 11, 2011 my thoughts have changed a little. Of course, these hopes may be simply the impetuous thoughts of someone who's still alive. Only those who remain living can decide the way of funerals. I just want my family to hold a ceremony for me that contains even just minimally a little bit of my own thoughts. Finally, I am thankful that my ending note has become a topic of conversation among many people. (March 2012, towards nirvana)

By 2019, she had stopped writing in her ending note, tired by the loss of her first ending note and constant revisions. Rather than an ending note, it had become a diary.

As seen above, people's thoughts about their lives keep changing. The case of Mrs Waku resonates with Susan Orpett Long's point: death is a social event interpreted by all parties involved, including the family members of the deceased.Footnote 36 In order to respect the wishes described by Mrs Waku in her ending note, her relationships with others needed to remain the same. However, they kept shifting, which led to changes in Mrs Waku's thoughts. As such, the preparations for one's death cannot but reflect the dynamics of Japanese social and cultural relationships that are embedded within a life course.Footnote 37

Ms Sumida's case

Would the problems caused by not preparing for death ahead of time be resolved by writing the ending note in accordance with the shūkatsu discourse, which calls for the early writing of ending notes for the sake of the families that are left behind? In order to answer this question, I will turn to the case of Ms Sumida. In 2019, I interviewed Ms Sumida, who works as a shūkatsu counsellor. Advising the elderly about dying, she came to consider ending notes as an important tool of self-reflection. For instance, she realized how, in writing their ending notes, the elderly had the opportunity to think about how they would dispose of personal items, such as photographs. While such items were of little monetary value, they held great sentimental value for the elderly, leaving their surviving families in a moral quandary of how to dispose of them. Because of such dilemmas, Ms Sumida, as a shūkatsu counsellor, firmly believed that shūkatsu was needed and so she spent her days counselling the elderly about their final days. She also spent time helping her parents in their family business of selling burial plots which gave them many opportunities to discuss death. Her mother, for instance, made explicit her wish not to be put on life support should she suffer from a disease or illness.

Even though Ms Sumida had fully confirmed her mother's wishes during her lifetime, she was unable to fulfil them. One day, her mother suffered a stroke and was rushed to the hospital. After regaining consciousness, she was paralysed and could not move her body or speak. Despite her mother's wish to refuse life-prolonging treatments, Ms Sumida felt that she had no choice but to put her on life support. Luckily, she was backed up by her siblings in making this tough decision regarding their mother's care.

Through the incident with her mother, Ms Sumida came to realize that no matter how early one prepares an ending note, it will be difficult for the remaining family members to follow it completely. Still, Ms Sumida, who is single, was afraid of what would happen if she were in a similar situation. In her own ending note, she wrote that if she were found unconscious in her home, her siblings should not take her immediately to the hospital. Instead, they were to wait at least a day to see if she regained consciousness. She was afraid of putting her siblings—especially her elder brother—in a burdensome situation. When I asked whether she thought her elder brother would respect her wishes, she shrugged her shoulders. It was likely to be as difficult for him to make that decision when the time came, she said, as it had been for her with their mother.

Ms Sumida's case shows that family members have as much difficulty as the elderly in reducing the meaning of death to the mere disposal of material remains; and they find it hard following through the wishes of the elderly, as they themselves do not know how they will react when the time comes. Further, even though Ms Sumida tried to establish her post-self through her ending note, she realized she would be unable to completely control the situation following her death. Paradoxically, this anxiety created even greater pressure on her to prepare more for her death. In this way, the attempts to create a post-self through the use of ending notes were not helping people die in the way they wanted, but, rather, created greater anxiety around the fact that they would not be able to control death in the way they had sought to. As a result, the ending note did not relieve anxiety about dying, but instead became a deep dilemma for the families of the elderly.

Mrs Sakurai's case

Mrs Sakurai, 75, lives in a cooperative association for the elderly, where she leads seminars on shūkatsu. Not only does she introduce its members to the latest funeral arrangements, including natural funerals, she also advises them on writing ending notes. However, she herself does not have an ending note. Asked why, Mrs Sakurai replied,

Looking back and organizing one's past is a very important matter. However, it's hard to write down exactly what I want for my funeral, including who should be contacted. We don't know when we will die and things keep changing. So I simply tell my children, ‘Just do what you can do.’ Of course, it is bit difficult since one is not directly in charge of the funeral proceedings. Even though I've left instructions for my ashes to be scattered into the sea, I know that's a difficult thing to do in practice. I also wonder whether it's really ok to do something like that [scatter my ashes into the sea].

I gave my own mother a new ending note before she passed away. Even as she neared a century of living, she didn't have the heart to write in it. (Laughs) It was as expected. I think she felt sorry to write down her wishes. She wanted to do what she could do by herself.

Instead, when my mother turned 100 years old, I held an exhibition of all the dolls that she had handsewn. At the time, many acquaintances and relatives came to celebrate with her. My mom was so happy to see them. I wonder if that was her way of saying goodbye to the world.

In Mrs Sakurai's response, we can see many dilemmas involving ending notes. First, she does not consider death to be something that anyone can plan for. She is also worried about burdening her family members with requests after her death. She is afraid that they would feel guilty if they did not satisfy all her requests. This is especially true for the Shōwa hitogeta generation (born during the first decade of the Shōwa period), who are fearful of being a burden on others. Raised during wartime, they are not used to asking their families or friends for help.

Mrs Sakurai's case reveals an ironic dimension to ending notes. Shūkatsu professionals are seen to encourage the self-responsibility of the elderly in managing their own deaths and, thereby, reduce the burden they place on others. Yet, such ending notes do become burdensome on their surviving family members, tasked with the job of executing the requests of the deceased. In fact, a survey of 3,494 people over the age of 60 found that 85 per cent of them knew about ending notes. However, only 6 per cent of them—5.6 per cent of men and 6.9 per cent of women—actually kept them. This was because they knew the increased burden that their ending note would place upon their surviving family members.

The various dilemmas experienced by Mrs Waku as she prepared for her death tell us that death—like life—is not something that can be predicted or controlled. Of course, the endless questions in the ending notes can still be helpful in encouraging the elderly to think of how they will dispose of the biological and material traces of their lives. However, they cannot provide an answer to fundamental questions regarding death. Ultimately, the narrative of a person's death remains to be completed by those who are left behind. As a result, even though many elderly understand the need to write ending notes, they ultimately do not bother doing it. Through neglecting to write ending notes, the elderly try to resituate death—which has been reduced to the disposal of their material remains—in the sphere of ethics and sociality.

Conclusion

This article has examined how shifting social and material relations between the elderly and their families, society, and the government are resulting in new norms and practices for the disposal of the elderly's bodily remains after death, by investigating the reconfiguration of necrosociality within the late-capitalist Japanese society.Footnote 38 Recently, within Japanese society, the rituals and ‘practices to prepare for one's own death’, created as part of social welfare programmes, have emerged. They strive to prevent social death and purify death of its dangerous and disgusting elements. The efforts are being exerted to ensure that all aspects of death—including embalming, burial, and inheritance—are properly planned for and managed. The reason for these efforts to drive out ‘bad deaths’, such as dying alone or abandoned, through shūkatsu, can be found within this context. With the fall in the social status of death and its medicalization, the meaning of ‘bad death’ is also undergoing a change.

In the context of neoliberal governance intent on maximizing human resources, the elderly are pressured to think ahead to the costs and burdens of disposing of their dead bodies and belongings. Therefore, the elderly face the social demand for them to leave instructions on how their bodily and personal remains should be dealt with when they die through ending notes. The elderly are also pressured to attend to the materiality of their deaths by making sure that their corpses are properly decomposed and the urns are buried in their proper designated spaces. Within these shūkatsu discourses, dying is treated as simply a matter of making sure that all the material traces of one's life are properly disposed of, so as to not become a burden on others.

It is possible to see the act of writing an ending note as technologies of the self to create a neoliberal self that monitors and manages death. The shūkatsu discourse even urges the elderly to build their own post-selves in order to prevent having bad deaths. However, through examining their experiences, the elderly and the shūkatsu experts have come to realize that death—like life—is not something that can be predicted or controlled. The attempt to control death by rationalizing it is a fundamental act of negating it.Footnote 39 The elderly have realized that, as an absolute negation of existence, death is not something that can be rationally tamed. Simultaneously, the elderly are concerned that writing ending notes will increase the burden on their families to fulfil their wishes. Recognizing that they cannot know and decide everything regarding their own deaths ahead of time, many are leaving the decision-making up to their family members. They thus acknowledge that their own life narratives are to be completed by others, including their family members or friends. For the elderly, death is not an event, but a social project to be carried out with the help of others. Therefore, the practice of the elderly who refuse to write an ending note has significance as an act of resistance against the rule of neoliberalism and as a practice of a new politics of life and death.

In this manner, the politics of life and death in Japan is being enacted through the elderly's changing social relations with their families, neighbours, and the government. By reflecting on the appropriate way to behave under the gaze of others and their corresponding social relations, the elderly are remaking the ethics of dying. In such a manner, the politics of life and death within contemporary Japanese society is being enacted through material exchanges with diverse people who have died, as well as in the preparations for the deaths of people who remain living.

Competing interests

None.