Introduction

What determines which problems are addressed through international norms? Is it their severity, their framing, their visibility? And how do these factors affect each other? Numerous studies on international norms suggest that active and committed norm entrepreneurs, who raise problem awareness, construct a resonant framing, mobilise their audience, pressure the norm addressees, and create conducive institutional conditions, matter most for norm emergence.Footnote 1 But what about those cases where these conditions seem to be present, and yet, the norm-setting process fails?Footnote 2 This article highlights the decisive role of issue salience in explaining such outcomes by showing that high salience facilitates norm emergence, while low salience inhibits it.

Recently, several authors have urged to study salience systematically.Footnote 3 But since salience is not a completely unknown concept to norm research, why is it worthwhile to take up the plea and what is the new argument about salience that this article makes? First, paying attention to attention sensitises us to the discrepancies between the severity and urgency of some problems and their visibility – discrepancies that matter because one of their consequences is that certain problems are neglected by both norm entrepreneurs and by political decision-makers. Second, central norm-related concepts like agenda-setting and awareness-raising suggest that issue salience is a result of advocacy,Footnote 4 but I argue that salience has a distinct explanatory value in that it affects advocacy decisions.

Third, the term salience is being used inconsistently in norm research, denoting rather different features of norms, which are, moreover, already covered by other concepts – like strength,Footnote 5 resonance,Footnote 6 internalisation and acceptance,Footnote 7 influence,Footnote 8 or prominence and commitment.Footnote 9 In contrast, this article makes a case for a narrow definition of salience, which is common in communication and agenda-setting research,Footnote 10 but rare in norm research:Footnote 11 Salience is defined as the amount of attention granted to an issue and reflected in agendas – ‘set[s] of issues that are viewed at a point in time as ranked in a hierarchy of importance’.Footnote 12 In addition to providing a well-defined focus of study, this attention-based understanding opens space for a differentiated analysis and allows comparisons, for example, of the salience of the same norm to different audiences or over time, as well as of the salience of different norms.

The present study demonstrates the theoretical and empirical value of salience with regard to norm emergence, but salience is also worth further exploration with regard to other aspects of norm evolution, namely norm diffusion and norm erosion. The international diffusion of norms is usually captured through the adoption of respective legislative acts and/or through norm-compliant behaviour.Footnote 13 Studying the salience of these norms might complement the picture (or produce a different one) by revealing how they took hold, and it might explain the patterns observed in law and compliance. Also, while I will show a positive relationship between salience and norm emergence, the effects of salience on norm diffusion appear to be ambivalent.Footnote 14 Regarding norm erosion, if we extrapolate from Martha Finnemore’s and Kathryn Sikkink’s argument that internalised norms ‘acquire a taken-for-granted quality and are no longer a matter of broad public debate’,Footnote 15 increases in salience might help detect eroding international norms and reveal when the erosion began.Footnote 16

The main argument of this article is that salience, generated through journalistic selection, issue attributes, and attention dynamics, affects norm emergence through its impact on four other factors, namely on norm entrepreneurs, mobilisation, social pressure, and framing. Salient issues will be more likely adopted by gatekeepers and promoted by norm entrepreneurs. Furthermore, salient issues will more likely inspire mobilisation and social pressure. For framing, salience functions as a precondition of becoming noticeable – the most resonant framing will not be effective if its addressees are not aware of it.

To probe the hypothesised relationship between salience and norm emergence, I focus on the issue area of inhumane weapons, and in particular, on the adoption of the norm against incendiary weapons and the non-adoption of the norm against cluster munitions in the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW).Footnote 17 This focus is suitable for my purposes for three reasons. First, the fact that the adoption of CCW in 1980 exhibits simultaneous instances of both emergence and non-emergence of norms allows for controlling for alternative explanations, and thus, for assessing the relevance of salience. Second, I posit that salience particularly matters in contentious processes – and norms regulating the use of certain weapons are usually met with resolute resistance because they belong to the essential domain of security policy. Third, and additionally to its theoretical aspirations, this article contributes empirically to research on weapons prohibitions by analysing original data on two cases that have not received much attention thus far: Neither is there a study tracing the emergence of the norm on incendiary weapons,Footnote 18 nor is there one attempting to explain the failure to prohibit cluster munitions in the 1970s.Footnote 19

Understanding why norms against some weapons emerge but not against others is inherently relevant because these norms save lives. But even in the large body of insightful research on non-use norms on certain weapons, this puzzle has not been sufficiently addressed. Most of the (single case) studies were pursuing other research aims: to demonstrate that and how weapons norms matter in shaping state behaviour,Footnote 20 to trace the evolution of the taboos on particular weapons,Footnote 21 and to examine the role of specific institutions in weapons development.Footnote 22 Stressing the importance of the social construction of inhumanity, this research has identified central discursive stigmatisation figures such as the weapons’ destructiveness, their secrecy, their long-term impact or their association with weakness and uncivilised warfare. Only recently and sporadically, a comparative perspective is emerging, which draws attention to the contingency of these discourses and highlights resulting inconsistencies of the practices of weapons regulation – namely, banning certain weapons while ignoring other weapons whose effects might be considered equivalent.Footnote 23 It is this line of argument that I build upon and advance by arguing that we need to consider salience to understand why particular weapons are singled out for prohibition by the gatekeepers, and why some norm-setting efforts succeed while others fail.

Guided by the question of why the norm against incendiary weapons was adopted in the CCW and why the norm against cluster munitions was not, this article is organised as follows. In the first section, I introduce the theoretical argument by conceptualising salience and its impact on other explanatory factors. Subsequently, I develop the puzzle by providing details on both weapons and outlining their common characteristics. I then present the empirical results of my study, which show a striking discrepancy in the salience of the two issues. Synthetising the results, the next section explains why and how salience affected the outcomes of the two norm-setting processes. In the conclusion, I discuss the generalisability of the results.

Salience and norm emergence

Building on the insight that the media agenda is crucial for the fate of public issues,Footnote 24 one of the essential claims of norm research is that norm entrepreneurs initiate salience-generating media campaigns. While not disputing this assumption, in this section I introduce three factors other than norm entrepreneurship that facilitate issue salience; journalistic selection decisions, issue attributes, and attention dynamics. In the second step, I sketch out how salience may serve as a precondition both to norm adoption through norm entrepreneurs and to the very processes that norm entrepreneurs push forward.

Norm research acknowledges the media as essential allies of norm entrepreneurs, disseminating the latter’s messages to the public.Footnote 25 However, the media do not only have the power to determine which issues are important enough to receive attention and to choose from a repertoire of topics, but also the power to initiate and promote their own issues and interests.Footnote 26 Since such initial media reporting is often necessary for norm entrepreneurs to learn about certain problems and to set them on their agenda,Footnote 27 journalistic selection decisions are a precondition to salience. The main factor affecting those decisions is the ‘news value’ of an issue, which is less determined by the inherent presence or strength of the attributes, but rather by how journalists perceive and construct them.Footnote 28 Among the main attributes increasing this value are so-called triggering events (characterised by unexpectedness, rarity, intensity, and/or spatial extent), ideally followed by related events, which produce a regular stream of new information.Footnote 29 Other attributes are personification, proximity, risks, controversy, and conflicts.Footnote 30

After the issues pass the initial selection filter, changes in salience over time, that is, rises and declines of attention, are driven by three main mechanisms of issue-attention cycles: attention thresholds and cascades, saturation effects, and issue displacement.Footnote 31 To take off, issues need to overcome the attention threshold, but once reached, a certain salience alone makes issues more attractive and stimulates a cascade – a rapid increase in attention. Cascades matter for other, related issues at the same time as they produce spill-over effects, and they matter for the same issue in the longer run, as it is easier to reactivate issues if they had reached a certain salience in the past because they appear familiar. Declines in salience are partly caused by saturation effects (or issue fatigue), which denote the exhaustion of interest for issues that have been salient for some time. This process is accelerated through the emergence of new issues – they have the capacity to displace old issues because their news value is higher and because they are in the more dynamic stage of the cycle.

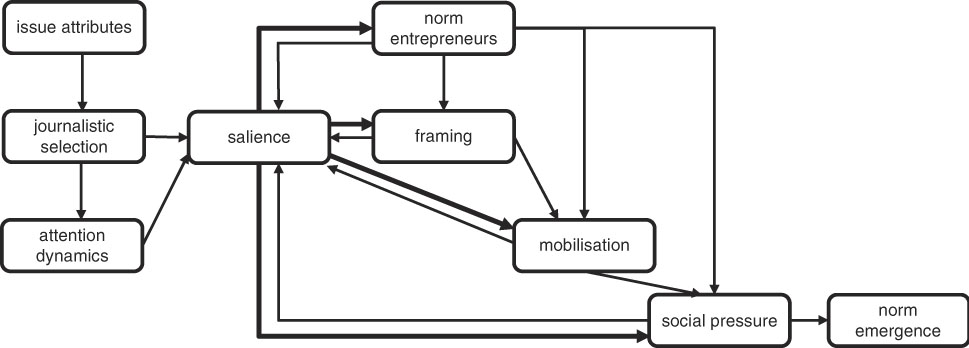

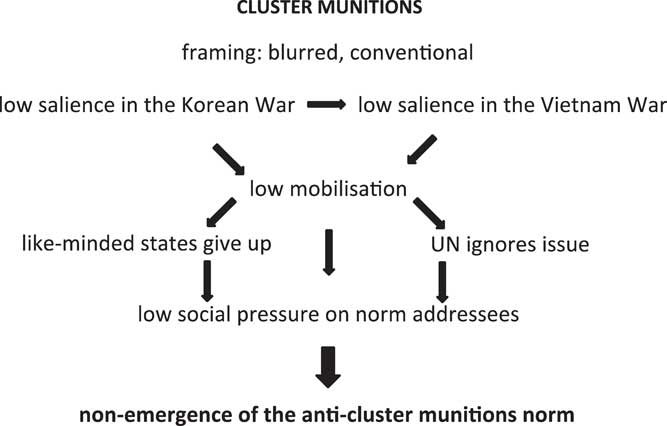

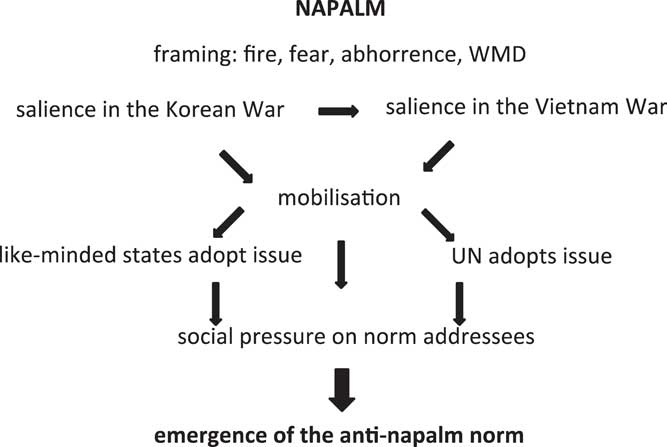

The model presented in Figure 1 hinges between previous and following sections by depicting the factors generating pre-advocacy salience and the factors usually deemed to be necessary for norm emergence, such as issue adoption by norm entrepreneurs, mobilisation, social pressure, and framing. Because we are dealing with mutual influence and multidirectional causality here, the model implies the causal path from norm entrepreneurship to salience, which has been established in the research on international norms already. Its focus, however, is on the reverse casual path – the one leading from salience to norm entrepreneurship and resulting factors.

Figure 1 The effects of salience on norm emergence.

The model concurs with norm research in assuming norm entrepreneurs to be the condition sine qua non for norm emergence.Footnote 32 It also echoes the research on the role of gatekeepers and on issue selection, which stresses organisational interests and strategic considerations in issue adoption decisions.Footnote 33 In determining which issues deserve transnational commitment, norm entrepreneurs assess whether an issue is easy to brand and to transmit, likely to acquire funding and to meet the interests of other institutional partners.Footnote 34 But issue salience, I argue, is an additional factor figuring into those calculations. Salient issues will be more likely adopted by gatekeepers and promoted by norm entrepreneurs for two reasons: These actors are more likely to become aware of salient problems, and they are more likely to invest their resources in salient issues because they deem the latter’s chances to be regulated as higher.

Another common assumption the model shares is that in contentious norm-setting processes, a high level of social pressure is necessary for norm emergence. Once the issue has been adopted, norm entrepreneurs increase social pressure on the norm addressees in two ways: indirectly, through addressing the ‘targets of mobilization’, and directly, through addressing the ‘targets of influence’.Footnote 35 The targets of mobilisation are actors with leverage (often the public, advocacy networks or other states) who are supposed to become active and to exert influence over the norm addressees. To mobilise them, norm entrepreneurs launch so-called awareness raising campaigns, which aim at increasing issue salience through information politics, consisting of instruments like reports, posters, or websites, and through action politics, consisting of instruments like demonstrations or fundraisers.Footnote 36 At the same time, due to cascade effects described above, mobilisation is more likely for issues that are salient already or have been salient in the past.

The targets of influence are the addressees of a norm themselves (mostly states, but also enterprises, or other non-state actors), that is, those actors who are supposed to adjust their attitude, or at least their behaviour, to the norm. Social pressure is supposed to affect their cost-benefit calculations by distributing social punishments and rewards.Footnote 37 To exert social pressure, norm entrepreneurs blame and shame the norm addressees by exposing norm-violating behaviour and norm-rejecting attitudes as well as casting their targets in a negative way.Footnote 38 In addition, praising (or altercasting), which is the other side of the coin, occurs. It refers to social rewards granted for norm support and the attribution of positive roles.Footnote 39 Same as mobilisation, social pressure does not only increase issue salience, but is also easier to exercise if it is related to issues that are salient already.

Framing is another established strategic element of norm-setting efforts that the model incorporates. Norm entrepreneurs use framing to define collective understandings of issues by ascribing meanings, defining categories, spinning narratives, grafting normative resources onto each other, embedding issues into normative networks, and using techniques like attribution, repetition, and association to promote certain perspectives on issues while excluding others.Footnote 40 While I agree that specific framing characteristics (for example, concreteness or simplicity) certainly explain why some issues become salient and others do not, my argument regarding salience and framing is twofold. First, I follow Maxwell McCombs and Salma L. Ghanem by arguing that salience is not only a distinct feature of issues, but also a feature of framing – strategic framing is all about making some attributes (and narratives and frames) more salient than other, competing attributes.Footnote 41 Second, I argue that issue salience is a precondition to the visibility of framing, since a framing that exhibits all favourable characteristics can still be invisible to the public.

In sum, in contrast to the literature that highlights the potential of norm entrepreneurs to increase issue salience through a favourable framing, mobilisation, and social pressure, I argue that issue salience itself affects those factors: Salience increases the chances of an issue to be adopted by norm entrepreneurs; it makes mobilisation and social pressure easier, and it allows the issue’s framing to become visible. Hence, I do not claim that salience is a rival explanation to the established ones. Rather, my interest is to study salience in conjunction with them and to demonstrate that it is a necessary element of the explanation, the consideration of which produces a more complete account of the emergence and non-emergence of norms.

Incendiary weapons and cluster munitions in the CCW: Background and alternative explanations

When the CCW negotiations began in 1978, several weapons, namely anti-personnel fragmentation weapons (known today as cluster munitions or cluster bombs), flechettes, fuel-air explosives, incendiary weapons, landmines, non-detectable fragments, and small-calibre weapons were proposed for restrictions because they were deemed particularly inhumane and contrary to the provisions of International Humanitarian Law (IHL).Footnote 42 The final document, however, only included protocols on three weapon categories: Protocol I prohibited the use of weapons producing non-detectable fragments; Protocols II and III restricted (but did not prohibit) the use of certain weapons – the former of mines and booby traps, the latter of incendiary weapons such as napalm. Following the logic of a most similar systems design, the different outcomes in the cases of incendiary weapons and cluster munitions seem to be the most puzzling, as both weapon types share some common characteristics regarding potential explanatory factors, namely inhumanity, military utility, and institutional setting.

Both incendiary weapons and cluster munitions qualify as inhumane due to their indiscriminateness and according to the criteria proposed by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).Footnote 43 Incendiary weapons burn people, often to death; cluster munitions tear them apart. Napalm-inflicted burns affect large areas of the human body and are especially severe, destroying the outer and the inner layer of skin as well as the tissue, nerve endings, and muscles, leading to third- or even fourth-degree burns.Footnote 44 Cluster munitions inflict large and deep wounds and penetrate the human body with tiny pieces of shrapnel; incidents with unexploded submunitions, which still occur long after the end of conflicts, lead to losses of limbs, blindness, and disfigurement.Footnote 45 The use of both weapons results in high mortality rates and extremely painful, severe, and large-area injuries, and both cause permanent disfigurement and disabilities to their survivors who might need complicated and long, often permanent, medical treatment.

Two observations invalidate the explanation that states merely agree to regulate weapons that they consider obsolete anyway.Footnote 46 First, massive uses of napalm and of cluster munitions in the Vietnam War indicate that both weapons were considered militarily effective.Footnote 47 Second, ban opponents stressed the military necessity of incendiaries and presented studies demonstrating their efficiency and superiority to other weapons at CCW negotiations.Footnote 48 And yet, a protocol restricting them was adopted eventually.

Another explanation that I exclude is the institutional setting. The latter is considered to provide (or lack) favourable conditions for persuasion,Footnote 49 and to determine the possibilities of norm entrepreneurs to influence outcomes via access, participation, and decision-making rights.Footnote 50 These factors, certainly playing a role in other cases, cannot explain the outcomes of interest here, since the norms on napalm and on cluster munitions were negotiated in the same institutional fora, and belonged to the same general norm-setting process that began after the Second World War and focused on a range of potentially inhumane methods and means of warfare.Footnote 51

Nevertheless, cluster munitions escaped a ban in the 1970s, whereas a norm on napalm emerged. Protocol III of the CCW prohibits the use of incendiary weapons against civilians and civilian objects, but also against military objectives located within concentrations of civilians and against forests and other kinds of plant cover except when these are used to conceal military objectives. The norm has been criticised as weak in legal terms,Footnote 52 but the social norm against incendiary weapons, and napalm in particular, is strong, despite occasional breaches.Footnote 53 Right after the adoption of the CCW, incendiary weapons were deemed to be those conventional weapons that invoked the greatest public revulsion and that were outlawed even without a legal ban.Footnote 54 Today, authors still diagnose a ‘near universal antipathy to napalm’ amounting to the extent of ‘public hysteria’.Footnote 55

Meanwhile, a norm on cluster munitions has been adopted as well: In 2008, the so-called Oslo Process resulted in the Convention on Cluster Munitions, which not only fully prohibits their use, but also their stockpiling, production, and transfer. Finally, the inhumanity of these weapons has been recognised by international law. But what explains the initial failure of this norm – and the success of the anti-napalm norm?

Method and data

Following observations would support my argument. The basic expectation is that the outcomes of the norm-setting processes correspond to the salience of the issues: the emergence of the anti-napalm norm should have been preceded by a high salience of the napalm issue; the non-emergence of the anti-cluster munitions norm should have been preceded by a low salience of the cluster munitions issue. Moreover, we should find that issue salience corresponds to other factors, that is, that high salience co-occurs with issue adoption by gatekeepers, high mobilisation, and high social pressure, whereas low issue salience does not. But since these relationships are multidirectional – how can we know what contributed to what? If consistent patterns of discrepancies are observed, the argument that salience affected the other factors and not vice versa implies a certain temporal succession,Footnote 56 namely that discrepancies in salience occurred first, and discrepancies in other factors followed. To show that the visibility of framing matters, the framing substance of the two weapons should be similar, and the framing salience should be different.

The observations are drawn from both secondary sources and primary data, which shed light on the public and the institutional developments of the two norms of interest. The period covered by primary data (Table 1) begins on 1 January 1945, and accounts for the fact that both weapons were used on a large scale during the last months of the Second World War, and for the fact that the formalisation of international humanitarian law began after this war.Footnote 57 It ends on 10 October 1980, the date of the adoption of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons.

Assuming the media discourse to reflect dominant political and societal discourses, I analysed the discourse in The New York Times and in The Guardian.Footnote 58 The New York Times is often considered to be a newspaper of global scope, read by international decision-makers.Footnote 59 The Guardian was included to correct the bias of the US-based New York Times during the Vietnam War,Footnote 60 and because criticism of the use of napalm had been voiced in Great Britain already during the Korean War.Footnote 61 Furthermore, The New York Times regularly included press clippings and letters to the editor from diverse regions of the world, which at least reduces the Northern bias problem (as does the institutional discourse in which speakers from all over the world were represented).

To cover the institutional discourse, I focused on three institutions where the norm-setting processes on napalm and cluster munitions unfolded: the ICRC, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and the United Nations Conference on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons Which May be Deemed to be Excessively Injurious or Have Indiscriminate Effects (UNCCW).Footnote 62 The ICRC process included the conferences of government experts (CGE) in 1971 and in 1972 in preparation of the Diplomatic Conference on the Reaffirmation and Development of International Humanitarian Law Applicable in Armed Conflicts (CDDH) as well as the Ad Hoc Committee on Conventional Weapons of the CDDH, which met in several sessions between 1974 and 1977. The United Nations General Assembly and its relevant subcommittees regularly discussed the topic of inhumane weapons in the 1970s. The UNCCW met in one preparatory and two main sessions between 1978 and 1980.

Table 1 Final document sample. All documents were coded twice following the method of content analysis.

Theory vis-à-vis the cases: Observations on salience and the norms against incendiary weapons and cluster munitions

Public salience, mobilisation, and social pressure

In the public discourse, the salience of the napalm issue exceeded the salience of the cluster munitions issue by factor 7.3. Except for two years (1945 and 1978), napalm was consistently the more salient issue (Figure 2 and Table 2)

Figure 2 Public salience, mobilisation, and social pressure in coded segments per year (1945–80).

Table 2 Public salience, mobilisation, and social pressure. ()=percent, distribution between the cases; ()*=percent, distribution within the case.

. The mobilisation, which I measured through the frequency of mobilising events, such as demonstrations, symbolic actions, press conferences and other public statements, mentioned in the media, was 14 times higher for napalm than for cluster munitions. Social pressure, which I measured through the frequency of statements blaming and shaming particular actors for issue-related actions, such as using, producing, or trading the weapons in question, was eight times higher for napalm.Footnote 63

The napalm issue took off during the Korean War (1950–3), achieving the attention threshold due to a regular stream of information through daily United Nations communiqués and other articles on the daily progress of the war, which simply stated that napalm, among other weapons, was being used in combat (Figure 3)

Figure 3 Public salience, mobilisation, and social pressure in coded segments per month (1950–3).

. The issue had maintained a relatively high salience level for 12 months, before first acts of social pressure occurred, and for almost 2 years, before first acts of mobilisation occurred. These acts – mainly letters to the editor,Footnote 64 but also statements from churchesFootnote 65 and resolutions by civil society organisationsFootnote 66 condemning napalm – were triggered by an article that interrupted the previous neutral reporting by describing in detail a person who had been struck by napalm.Footnote 67 The report caused an outrage precisely because people had previously been reading daily about napalm without being alerted to its effects and were now shocked to learn what the weapons really did: ‘Information from various sources concerning military operations in Korea creates the impression that the new weapon known as the napalm bomb is more horrible in its effects upon the human body than any previously used weapon of warfare except the atomic bomb.’Footnote 68 After this brief outburst, the issue’s salience dropped to its previous level and then declined completely when the Korean War ended.

The decline was only temporary (Figure 4)

Figure 4 Public salience, mobilisation, and social pressure in coded segments per year (1960–80).

. At the beginning of the sixties, napalm re-entered the debate politicised: Portugal was criticised for having used napalm in Angola, and France was criticised for having used napalm in Tunisia. A steep increase in salience occurred when the US officially entered the Vietnam War in 1965. This war has fuelled the information stream related to napalm with two different components: war reporting and mobilising events. In total, both contributed to napalm’s salience almost equally, but their proportions changed over time: In the first years of the war, reports about the use of napalm in the war prevailed, but from 1967 to 1970, reports related to mobilising events prevailed.

At its outset in the first half of the 1960s, mobilisation was largely marked by letters to the editors, voicing opposition to the Vietnam War and its atrocities, of which the use of napalm was one. The French philosopher Bertrand Russell was the first to openly criticise US policy, including the use of napalm, in a letter to The New York Times in 1963.Footnote 69 The New York Times disputed Russell’s accusations,Footnote 70 but he insisted,Footnote 71 supported by others.Footnote 72 Less than one year later, it was again Russell, who criticised the use of napalm in a letter to The Guardian.Footnote 73

In 1965, mobilisation against the Vietnam War in general, and the use of napalm in particular, started to intensify and to diversify, both in forms and in actors. Various anti-war groups were writing open letters to President JohnsonFootnote 74 and running anti-war advertisements;Footnote 75 members of the UK parliament were addressing the president in telegrams;Footnote 76 and Soviet representatives were criticising the war in speeches at the UN and elsewhere.Footnote 77 The first anti-war demonstration referring to napalm was mentioned in April 1965,Footnote 78 and, with some delay, many other protests marches, sit-ins, and pickets followed.Footnote 79 Various other mobilising actions, like the burning of draft files with napalm, on-site visits in Vietnam, or fundraisers for napalm victims, took place.Footnote 80

After the wave of major protests receded, the issue remained salient because the stream of information was still present, but both salience and mobilisation declined until the end of the Vietnam War (with the exception of 1972 when the photo of the Trang Bang incident showing children fleeing from napalm was published).Footnote 81 After this war, uses of napalm in other conflictsFootnote 82 kept the issue on the agenda, but on a lower level.

In contrast, the cluster munitions issue never achieved the attention threshold necessary to take off, despite a moderate increase in salience during the Vietnam War and a short-lived peak in 1967. The components of the information stream that made napalm salient were largely absent here. Cluster munitions were never mentioned in the context of the anti-war demonstrations,Footnote 83 and they were neither mentioned in regular war reporting, nor were there articles of other symbolic anti-war actions featuring cluster munitions. The issue’s highest salience peak in 1978 also was not enough to establish CM as an issue, as it was linked to one single event (an export scandal related to the US supply of cluster munitions to Israel, which the latter had used against civilian targets in Lebanon), and lacked follow-up events, which would have sustained the attention. While less conspicuous due to the low issue salience, the case of cluster munitions nevertheless supports the finding that mobilisation and social pressure require a certain degree of salience: the issue was lowly salient for about two years before mobilisation and social pressure set in.

These observations support the general expectation that salience matters for the emergence and non-emergence of norms: The issue with a consistently higher salience emerged as a norm, the issue with a lower salience did not. Also, both expectations regarding sequence were confirmed. First, napalm, which had already been an issue during the Korean War, easily recaptured the public’s attention during the Vietnam War.Footnote 84 In contrast, cluster munitions struggled to come up as a new issue. The anti-war mobilisation and the anti-US criticism spilled over to both issues, but they did so to napalm to a much larger extent. This indicates that the cascade effect also applies to mobilisation and social pressure – not only does an issue’s previous salience make it easier for an issue to become salient again, but it also accelerates mobilisation and social pressure, in particular, if both had occurred to a certain extent in the past. Second, in both cases, issue salience preceded mobilisation and social pressure. However, it remains puzzling why napalm’s mobilising effect was that much higher. In the following section, I analyse how the framing of the weapons contributes to the explanation.

Framing

The represented practices of use of both weapons were similar (Table 3)

Table 3 Framing. Aggregated data from media and institutional documents. ()=per cent, distribution between the cases; ()*=per cent, distribution within the case.

. Napalm and cluster munitions were most strongly associated with the same big conflict (the Vietnam War) and the same major users (the US and Israel). In both cases, the majority of mentioned targets were military, but the majority of mentioned victims were civilian. While these categories were similarly salient within the respective discourses, the absolute numbers of corresponding codings varied considerably between the two cases. For example, napalm was mentioned in the context of the Vietnam War almost ten times as often as cluster munitions,Footnote 85 and was associated with attacks against civilian targets as well as with civilian victims about seven times as often.

To stigmatise the weapons, a set of similar attributes was used, but the stigmatising framing of cluster munitions was more obscure and much less salient than the stigmatising framing of napalm. There was an overlap of stigmatising attributes attached frequently to both weapons: In the public discourse, ‘death’, ‘injury’, ‘children’, and ‘destructive’ were among them. In the institutional discourse, again ‘death’ and ‘injury’, but also ‘indiscriminate’ and ‘causing unnecessary suffering’ were attached frequently to both weapons, which demonstrates that both cluster munitions and napalm were perceived to conflict with respective IHL principles.

Four important differences are to be mentioned here: First, the framing of napalm revealed how this weapon caused destruction (namely by associating it with fire and burn injuries), but the framing of cluster munitions did not – both a pendant to fire and mentions of specific injuries lacked.Footnote 86 Second, the association of napalm with fire stimulated another attribute, which, however, was ascribed to cluster munitions only twice: fear. This fear, which is suggested to be rooted in different sources,Footnote 87 had a powerful stigmatising effect: ‘People have this thing about being burned to death’.Footnote 88 Third, the shares of stigmatising speech acts were higher for napalm by 16 percentage points in the public discourse, and by 9 percentage points in the institutional discourse. In the latter, stigmatising speech acts clearly prevailed with a share of 80 per cent in the case of napalm, and with a share of 71 per cent in the case of cluster munitions, while in both public discourses, stigmatising speech acts constituted less than 50 per cent. Fourth, the differences in absolute numbers – and thus, in the salience of specific frames – were immense: Main attributes, such as death and children, were attached to napalm up to 11 times as often as to cluster munitions; and the overall number of stigmatising attributes was six times higher in the napalm than in the cluster munitions case. Napalm-related stigmatising speech acts exceeded cluster munitions-related speech acts by factor 11 in the public discourse, and by factor 7 in the institutional discourse.

Both weapons were embedded in similar normative frameworks, but the strength of this embeddedness varied. The association with conventional weapons was strong in both cases, but in the napalm discourse, the share of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) references was by ten percentage points higher than in the cluster munitions discourse. In absolute numbers, WMD references in the napalm discourse exceeded WMD references in the cluster munitions discourse by factor 10. As to normative references, IHL was the most frequent grafting resource for both napalm and cluster munitions, but the absolute number of normative references was seven times higher in the napalm discourse.

These results demonstrate that framing and salience should be treated as complementary rather than as competing explanations. On the one hand, the stigmatisation of cluster munitions lacked some important aspects, which explains in part why the issue had such weak mobilising effects and did not become salient. On the other hand, cluster munitions weapons were being stigmatised, but their framing was almost invisible and not present in the public conscience, whereas the framing of napalm had reached the public. If the issue as such had caught more attention, its stigmatising frames would have become more salient, too.

Norm entrepreneurs and problem adoption

Two actors qualify as norm entrepreneurs for the cases in question, namely the ICRC and the United Nations Secretaries-General (UNSG). The ICRC’s mandate to serve as the ‘guardian of international humanitarian law’Footnote 89 as well as its prominence among (humanitarian) arms control actors qualify the organisation as a gatekeeper.Footnote 90 The UNSGs, addition to their role as chief administrators, serve as normative authorities by using their symbolic and representative power to support the creation and implementation of global norms.Footnote 91 The commitment of the ICRC and the UNSGs to the two norms in question varied. The ICRC acted as a norm entrepreneur for both napalm and cluster munitions; the UNSGs acted as norm entrepreneurs for napalm, but neglected cluster munitions. Does salience explain the variance in problem adoption?

Problem adoption by the ICRC reflected the varying levels of salience between the issues and over time. After the Korean War, during which only napalm had gained salience, the ICRC, too, had turned its attention to napalm only: In 1956, it issued the ‘Draft Rules for the Limitation of the Dangers Incurred by the Civilian Population in the Time of War’, where in Article 14, incendiary weapons and delayed-action weapons were the only conventional weapons proposed for prohibition. After cluster munitions had gained at least some salience during the Vietnam War, the ICRC tasked a group of governmental experts to examine the conformity of certain conventional weapons, including napalm and cluster munitions, with IHL. Eventually, the ICRC set both weapons on the agenda of the Ad hoc Committee of the CDDH.Footnote 92

The UNSGs, in contrast, consequently focused on the salient issue, napalm, and ignored cluster munitions. In 1970, Secretary-General U Thant issued a report on human rights in armed conflicts, which called upon states to prohibit or restrict certain means of warfare, namely weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and napalm.Footnote 93 His second report, issued in 1972, was devoted solely to napalm and stressed the necessity of prohibitions or restrictions on its use.Footnote 94 The next report, issued by U Thant’s successor Kurt Waldheim in 1976, dealt with all weapons discussed in the Ad hoc Committee, but its title singled out incendiary weapons.Footnote 95

The differences between the ICRC and the UNSGs have two implications for the relationship between issue salience and problem adoption. First, the ICRC was less affected by issue salience in its selection decisions than the UNSGs. The ICRC, too, stated that it tried to mirror the ‘global public opinion’ with its efforts,Footnote 96 but in addition, the organisation had systematically considered potentially inhumane weapons and made deliberate choices. The UNSGs, however, considered it as within the UN mandate to reflect the public spirit and thus picked up the issue that had figured prominently in public attention. Second, the problem adoption by the norm entrepreneurs affected issue salience in the negotiations in the respective institution, as the following section shows.

Institutional salience, social pressure, and norm emergence

The institutional negotiations evolved in two sequences: The first round took place in the Ad Hoc Committee from 1974 to 1977; the second in the UNCCW from 1978–80. In the Ad Hoc Committee, a group of seven like-minded states, led by Sweden and including Egypt, Mexico, Norway, Sudan, Switzerland, and Yugoslavia, initially had pushed for bans on both napalm and cluster munitions. This had an effect on issue salience: In the first session in Lucerne, cluster munitions were almost ignored, and the attention devoted to napalm exceeded the attention devoted to cluster munitions by factor 5.8. But in the second session, the attention to the latter rose considerably, and the salience gap narrowed to 2.6 (Figure 5

Figure 5 Institutional salience of cluster munitions and napalm in coded segments per year (1968–80).

and Table 5).

In the Lugano session in 1976, however, the group’s commitment to cluster munitions dissipated. The proposal on cluster munitions had met with resistance, and the discussion quickly centred on issues with greater potential for agreement, of which napalm was one.Footnote 97 Consequently, napalm’s salience increased by more than 50 per cent, while the salience of cluster munitions slightly declined; the salience gap widened again to 4.4. Eventually, the majority agreed that restrictions on incendiary weapons – and on landmines and undetectable fragments, but not on cluster munitions – were needed, but since the delegates could not agree on any specifics, they called upon the UNGA to conduct another conference.Footnote 98

The common ground that began to emerge in the Ad Hoc Committee solidified at the UNCCW. During the Preparatory Conference, the like-minded group, which now included some new members and all previous members with the exception of Norway, continued to demand a prohibition of incendiary weapons, but not on cluster munitions.Footnote 99 Solely Mexico had not given up on the issue completely and submitted a draft clause including a prohibition on cluster munitions as well as a draft of an umbrella treaty, which would include a protocol on cluster munitions.Footnote 100 But this effort was futile: Cluster munitions did not gain ground in the debate, and neither an informal plenary nor a working group were devoted to them.Footnote 101 Consequently, no draft protocol on cluster munitions was submitted to the main conference that began six months later – but several draft protocols on napalm.Footnote 102 In the ensuing negotiations, the delegates were fully occupied with the unresolved specifics of the tabled proposals, with no capacities left to revive proposals that had slipped off the agenda already, among them the one on cluster munitions.

What role did social pressure play for these outcomes and how was it exercised? There was almost no public social pressure related to cluster munitions at the time of the conferences. But it had also dropped considerably for napalm: the Vietnam War was over, and so was the shaming of its users; the international negotiations received very little public attention.Footnote 103 In the institutional discourse, shaming was rare with regard to both weapons, but it still occurred five times more frequently for napalm (Table 4)

Table 4 Salience, stigmatisation, and social pressure in the institutional process. ()=percent, distribution between the cases; ()** CCW and ICRC only.

. Also, shaming was limited to UNGA debates – it almost never occurred in the ICRC and the CCW negotiations, which indicates that shaming is a public-oriented strategy, not necessarily fitting into a diplomatic environment.

Table 5 Examples of statements referring to public opinion and UNGA resolutions.

And yet, the effects of social pressure were more persistent than its actual exercise. The public discussion had calmed down, but the delegates felt under pressure to achieve results, at least with regard to napalm.Footnote 104 Speakers emphasised the public revulsion towards napalm and the public expectation that the conferences would achieve results. The condemnation of napalm by the international political community, which had begun in the early 1970s with reports of the UNSGs and UNGA debates and resolutions, was another source of pressure (Table 6)

Table 6 UN resolutions referring to napalm and cluster munitions.

.

Both UN institutions had largely ignored cluster munitions in their efforts, but kept criticising the use of incendiary weapons and demanding an international prohibition. The salience of napalm in UNGA debates exceeded the salience of cluster munitions by factor 20.6. The perceptions of the delegates matched this imbalance: In the ICRC negotiations and in the CCW, the delegates regularly referred to UNSG reports and UNGA discussions when discussing napalm but almost never when discussing cluster munitions. Also, while abstaining from shaming, the ICRC and CCW conference participants built momentum through expressing support for the norms in plenary meetings – again, with a huge imbalance towards napalm, in terms of the breadth and intensity of support.

Eventually, the adoption of Protocol III hinged on the United States and the Soviet Union. The US were reluctant to agree – and the USSR conditioned their approval on the approval of the US. In the final days of the conference, the pressure on both worked out: The echo of Vietnam War protestsFootnote 105 and the persistence of the like-minded group ‘shamed the U.S., and maybe the Soviet Union too, into a concession’.Footnote 106 When the US agreed, so did the USSR.Footnote 107 As delegates reported later, for some, to prohibit or to regulate incendiary weapons was a ‘dictate of the public conscience’,Footnote 108 and the ‘raison d’etre for the CCW’Footnote 109 – ‘any agreement on conventional weapons which did not include a Protocol on incendiary weapons would have the distressing appearance of a fire-brigade which had forgotten to bring the hose-pipe’.Footnote 110 The conference closed with a norm against napalm.Footnote 111

Synthesis: Explaining the emergence of the norm against napalm and the non-emergence of the norm against cluster munitions

The emergence of the norm against napalm and the non-emergence of the norm against cluster munitions can be explained as a path-dependent process, in which initial discrepancies in salience grew further and became decisive through influencing the visibility of framing, mobilisation, and social pressure. Cluster munitions enjoyed some attention for the first time before napalm did, namely in 1945, but their use did not spur any criticism. Timing and context explain why. After all the cruelties of the Second World War, the public was numb; moreover, ending this war had become the overriding concern trumping humanitarian concerns about means and methods of warfare. Furthermore, after years of bombing cities, cluster munitions did not stand out as a particular bomb. When they did – to a certain degree – more than twenty years later, there was no attentional or mobilising precedent to adhere to, so the attention they received was still low, and their framing, despite conveying that the weapons were destructive and indiscriminate, was lacking concreteness as well as visibility. In turn, mobilisation around these weapons as well as social pressure on their users remained low (Figure 6)

Figure 6 The non-emergence of the norm against cluster munitions.

.

For napalm, the Korean War in the early 1950s became a critical juncture. Then, the emotional and legal reprocessing of the Second World War had begun, the new international system was being institutionalised, and the public became increasingly sensitised to humanitarian and human rights issues, of which the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were one. These factors drew attention to methods and means of warfare and thus, to the use of napalm.

This first salience peak of the napalm issue facilitated the recapturing and cascading of public attention during the Vietnam War. At the same time, the controversy over the conflict as such spilled over to the weapon closely associated with this conflict. In a self-sustaining dynamic, the criticism of the Vietnam War and the criticism of napalm mutually reinforced each other. The stigmatisation of napalm particularly benefited from two aspects: First, the discursive inseparability of napalm, fire, and burns triggered widespread fear.Footnote 112 Second, despite being considered a conventional weapon, napalm was strongly linked to WMD – not so much because its effects were comparable to the effects of any of the three categories of WMD, but rather because the abhorrence it caused was similar to the abhorrence caused by WMD. (Figure 7)

Figure 7 The emergence of the norm against napalm.

Conclusion

This article argued that salience explains norm emergence through its impact on four other factors, namely on norm entrepreneurs, framing, mobilisation, and social pressure. Napalm, the issue with a consistently higher salience, emerged as a norm – cluster munitions, the issue with a lower salience, did not. Salience appears as a necessary condition for other factors: rises in mobilisation and social pressure as well as issue adoption by institutional norm entrepreneurs were preceded by salience peeks; the effectiveness of similar framings varied depending on their visibility.

As I borrowed the concept of salience from other established disciplines, namely communication and media research, a huge amount of previous theoretical and empirical work supports the general claim of this study that issue salience is a relevant factor in explaining political outcomes. But how generalisable are my findings with regard to research on international norms? Since the emergence of norms may be very different and contingent upon many factors, I am neither suggesting that salience is a sufficient explanation nor that it matters in all cases. But, concluding from the cases analysed here, I consider the findings to be potentially applicable to norm-setting processes displaying following features: bottom-up processes initiated outside of governmental policymaking spheres by transnational or institutional norm entrepreneurs; processes promoting norms that are likely to be met with governmental resistance; and processes promoting rather non-technical norms with primarily ethical implications, which have the potential to ignite public opinion.

In addition to a better understanding of individual cases, further applications of the model suggested here promise to advance the theoretical understanding of the interplay of salience and other factors relevant for norm emergence. In my analysis, I bracketed the effects of mobilisation, social pressure, issue adoption, and framing on salience, which was sufficient to explain the cases of interest here. Yet, in other cases, the influence might be mutual, or the other factors might precede salience. This invites formulations of other models as much as further specification of the conditions under which the respective models apply.

Acknowledgements

For excellent comments on earlier versions of this article, I am grateful to Charli Carpenter, Caroline Fehl, Marco Fey, Marcel Heires, Catherine Hecht, Carsten Rauch, Niklas Schörnig, the editors of the journal and the three anonymous reviewers. I also thank the participants of the Junior Scholar Symposium at the ISA Annual Convention 2015. Karl Buchacher and Sophie M. Behr provided tremendous research assistance and language editing.