In depressive disorder, on average, the risk of recurrence increases with every new episode Reference Kessing, Andersen, Mortensen and Bolwig1–Reference Kessing and Andersen7 and without active treatment the duration of successive episodes seems to increase, Reference Swift8–Reference Kraepelin10 whereas with treatment the lengths of episodes seems constant or to decrease. Reference Angst and Sachar11–Reference Kessing and Mortensen14 Further, it is a widely held clinical belief that the severity of depressive episodes also increases during the course of illness. However, few studies have investigated the severity of successive episodes during the course of illness. Reference Lewinsohn, Zeiss and Duncan15,Reference Maj, Veltro, Pirozzi, Lobrace and Magliano16 Lewinsohn et al found a tendency of increasing severity from the first to the third depressive episode, Reference Lewinsohn, Zeiss and Duncan15 and Maj et al found a significant increase in severity from first to third episode. Reference Maj, Veltro, Pirozzi, Lobrace and Magliano16

It was the aim of the present study to investigate whether the severity of depressive episodes increases during the course of illness in depressive (unipolar) disorder and to investigate the relationship with age and gender. Severity of the depressive episodes was defined in accordance with the ICD–10 diagnostic system and the study included a nationwide register-based sample of patients who had had first contact with psychiatric in- or out-patient hospital settings.

Methods

The register

From 1 January 1995, the national Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (DPCRR) started to include information on all patients who have had contact with the psychiatric hospital system in Denmark (i.e. in-patients, out-patients in clinic- or community-based psychiatric care). Reference Munk-Jorgensen and Mortensen17 No private psychiatric in-patient hospitals or departments exist in Denmark; all are organised within public services and report to the DPCRR. However, privately practising psychiatrists treat about 15 000 patients a year and do not report to the DPCRR.

All 5.3 million inhabitants in Denmark have a unique identification number (Civil Person Registration (CPR) number) that can be logically checked for errors, so it can be established with great certainty if a person has previously had contact with psychiatric services, irrespective of changes in name, etc.

The ICD–10 18 has been used in Denmark since 1 January 1994. Information on treatment intervention is not available.

The sample

The study sample was defined as all in-patients and out-patients (patients in clinic- or community-based psychiatric care) with a main diagnosis of affective disorder (ICD–10, code DF30–39). The period in which patients were included was from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2003.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of a single mild depressive episode (ICD–10, code DF320, 3200, 3201), a single moderate depressive episode (ICD–10, code DF321, 3210, 3211) and a single severe depressive episode (ICD–10, code DF322, 323, 3230, 3231) at the end of first contact was calculated. Similarly, at the second and subsequent contacts, the prevalence of recurrent depressive disorder, current episode mild (ICD–10, code DF330, 3300, 3301), current episode moderate (ICD–10, code DF331, 3310, 3311), current episode severe (ICD–10, code DF332, 333, 3330, 3331) was calculated. Some patients received a diagnosis of a single depressive episode even though at a prior contact they had a diagnosis of a depressive episode. Such diagnoses were reclassified as recurrent depression. In this way, the prevalence of mild, moderate and severe depression was calculated at each new treatment contact – as a total and by gender.

Additionally, the prevalence of depressive episodes with psychotic symptoms (ICD–10, code DF323, 3230, 3231, 333, 3330, 3331) and the prevalence of an auxiliary diagnosis were calculated at each contact. Categorical data were analysed with a chi-squared test (two-sided). In additional analyses mild, moderate and severe episodes were scored at 0, 1 and 2 respectively, and the average value was calculated at each episode for groups of patients according to gender, age at first contact (⩽40 years; 41–60 years; ⩾61 years) and period of first contact (1994–1996; 1997–1999; 2000–2003). The effects of gender and current age were estimated in logistic regression models with severe depressive episodes v. other episodes and psychotic episodes v. other episodes respectively, as outcomes. The SPSS software package for Windows, version 11.0, was used; P<0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Results

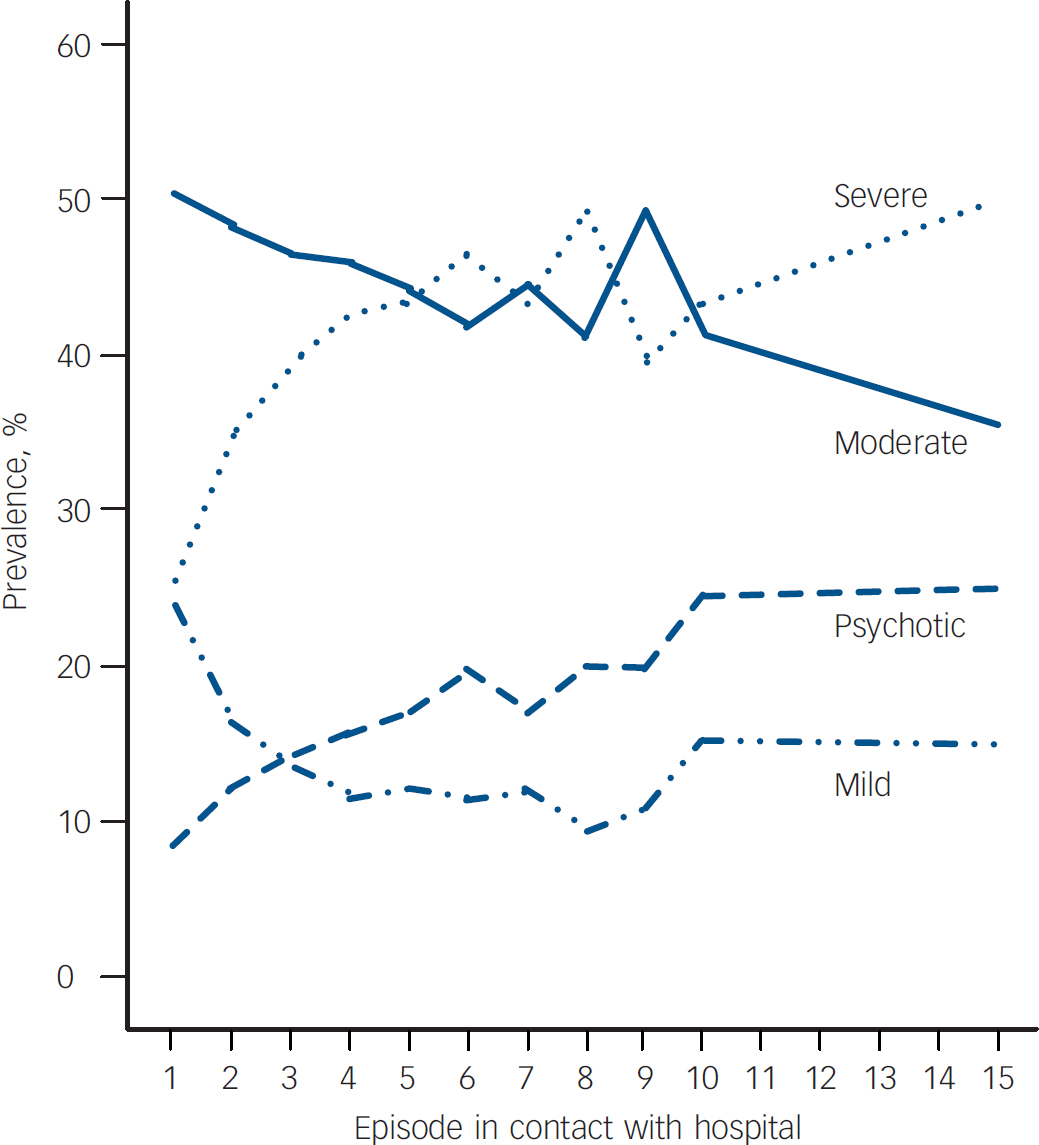

From 1995 to 2003, a total of 19 392 patients with a diagnosis of a single mild, moderate or severe type of depressive episode were identified; 64.1% of the patients were female and the median age was 50.8 years with a wide range – a quarter of the sample was younger than 33.7 years and a quarter was older than 72.8 years. A total of 24.0% of the sample had a mild depressive episode, 50.5% had a moderate depressive episode and 25.5% had a severe depressive episode. Furthermore, 8.7% had a severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (see online Table DS1). Among patients with a diagnosis of single depressive episode at first contact, 36.8% did not have a second psychiatric treatment contact within the hospital care setting, 45.2% (n=8767) received a diagnosis of recurrent depressive disorder, current episode mild, moderate or severe type at their second psychiatric treatment contact, 3.1% a diagnosis of persistent mood disorders or recurrent depression, currently in remission, 0.7% a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and 17.2% had a non-affective diagnosis at their second psychiatric contact. The 8767 patients with a diagnosis of recurrent depressive disorder, current episode mild, moderate or severe type, were selected for further analyses. The same procedure was undertaken at subsequent episode contacts (3–15) (i.e. at every contact selecting only patients with recurrent depressive disorder for further analyses). Table DS1 presents the prevalence of mild, moderate and severe depressive episodes as well as the prevalence of severe depressive episodes with psychotic symptoms at hospital contact (from 1 to 15) – as a total and according to gender. The prevalence of severe depressive episodes increased from 25.5% at the first contact to 50.0% at the 15th. Similarly, the prevalence of severe depressive episodes with psychotic symptoms increased from 8.7% at the first hospital contact to 25.1% at the 15th (Table DS1 and Fig. 1). In contrast, the prevalence of mild and moderate depressive episodes decreased during the course of the illness. The association between the episode number and the prevalence of severe depressive episodes could be a result of a selection bias, as patients with many episodes may have an increased prevalence of severe episodes from the beginning of their illness which could further dominate the analyses with regard to the number of episodes. Thus, in additional analyses, the association between the number of episodes and the prevalence of severe depressive episodes was stratified according to the total number of episodes during the study period. Also in these secondary analyses, the prevalence of severe depressive episodes increased with the number of episodes (results not presented).

Fig. 1 The prevalence of depressive episodes at hospital contacts 1–15.

The prevalence of auxiliary diagnoses increased from 17.2% at the first episode to 21.2% at the tenth episode but the prevalence of auxiliary diagnoses was inversely associated with the severity of the depressive episodes at all contacts (prevalence of auxiliary diagnoses in relation to mild/moderate/severe depressive episode: first contact 18.5%/17.8%/15.1%; tenth contact 61.5%/11.4%/16.2%; data not presented for other contacts).

In Table DS1, mild, moderate and severe episodes were scored at 0, 1 and 2 respectively, and the average value was calculated at each episode. As can be seen, the average increased from 1.02 (s.d.=0.70) at the first treatment contact to 1.35 (s.d.=0.74) at the 15th. This pattern was found for all groups of patients regardless of age at first contact (⩽40 years; 41–60 years; ⩾61 years), gender and period (1994–1996; 1997–1999; 2000–2003) as illustrated by online Fig. DS1.

More specifically, the pattern with an increasing prevalence of severe episodes and a decreasing prevalence of mild and moderate episodes with the number of hospital contacts was the same for males and females (Table DS1). However, males had a significantly higher prevalence of severe depressive episodes and psychotic episodes compared with females at the first two contacts. Borderline significant minor differences were found at a few subsequent contacts.

Table 1 shows the effect of gender (male v. female) and current age in logistic regression models with subtype of episode as outcome (severe episodes v. other episodes and psychotic episodes v. other episodes). As can be seen, it was confirmed that males had a higher prevalence of severe depressive episodes and psychotic episodes at the first two contacts, as well as when adjusted for the effect of current age. The prevalence of severe episodes increased significantly with age over the first five contacts but not at later contacts, when adjusted for the effect of gender. The prevalence of psychotic episodes continued to increase significantly with age for the first eight contacts, when adjusted for the effect of gender.

Table 1 The effect of gender and age on the prevalence of a severe episode v. other episodes and on the prevalence of a depressive episode with v. without psychotic symptoms

| Episode in contact with hospital | Male v. Female OR (95% CI) | Age, years OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| One | ||

| Severe | 1.18 (1.10–1.26) *** | 1.007 (1.005–1.008) *** |

| Psychotic | 1.16 (1.04–1.28) ** | 1.012 (1.010–1.015) *** |

| Two | ||

| Severe | 1.17 (1.07–1.29) * | 1.008 (1.006–1.010) *** |

| Psychotic | 1.18 (1.03–1.34) * | 1.013 (1.010–1.017) *** |

| Three | ||

| Severe | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) | 1.009 (1.005–1.012) *** |

| Psychotic | 1.03 (0.85–1.24) | 1.016 (1.012–1.021) *** |

| Four | ||

| Severe | 0.98 (0.81–1.18) | 1.006 (1.001–1.010) * |

| Psychotic | 0.90 (0.69–1.16) | 1.016 (1.010–1.022) *** |

| Five | ||

| Severe | 0.80 (0.62–1.04) a | 1.007 (1.000–1.013) * |

| Psychotic | 0.77 (0.55–1.10) | 1.014 (1.006–1.023) ** |

| Six | ||

| Severe | 0.86 (0.62–1.20) | 1.008 (0.999–1.016) a |

| Psychotic | 0.67 (0.44–1.04) a | 1.014 (1.003–1.025) * |

| Seven | ||

| Severe | 1.33 (0.86–2.05) | 1.004 (0.994–1.015) |

| Psychotic | 0.90 (0.50–1.63) | 1.029 (1.014–1.044) *** |

| Eight | ||

| Severe | 0.92 (0.52–1.60) | 1.009 (0.994–1.023) |

| Psychotic | 0.79 (0.38–1.65) | 1.028 (1.009–1.047) ** |

| Nine | ||

| Severe | 0.42 (0.18–0.94) * | 1.001 (0.983–1.020) |

| Psychotic | 0.50 (0.17–1.43) | 1.003 (0.981–1.027) |

| Ten | ||

| Severe | 0.45 (0.16–1.26) | 1.011 (0.986–1.035) |

| Psychotic | 0.39 (0.10–1.40) | 0.998 (0.971–1.026) |

a. 0.05<P<0.01

* P<0.05

** P<0.01

*** P<0.001

Discussion

This is the first study that systematically tested whether the severity of depressive episodes increases during the course of illness in depressive (unipolar) disorder. The study was a longitudinal investigation of a nationwide sample of all patients (in- or out-patients) treated for depressive disorder at first contact in psychiatric hospital settings. Data were collected as part of the daily routine and independent of research activities. The prevalence of severe depressive episodes increased substantially with the number of hospital contacts regardless of gender, age at first contact and period of first contact. These findings are in accordance with the findings in two other studies of an increasing severity from the first to the third depressive episode; unfortunately, they do not present data or more detailed results of the analyses as focus for these studies was relapse and recurrence and not severity of episodes. Reference Lewinsohn, Zeiss and Duncan15,Reference Maj, Veltro, Pirozzi, Lobrace and Magliano16 The results of the present study reveal that the severity of depressive episodes continues to increase throughout the illness after the third episode, with the same pattern for males and females, and regardless of age. In addition, the prevalence of depression with psychotic features increased with the number of contacts.

Females constituted 64.1% of the sample at the first episode contact and around 70% at subsequent contacts, in accordance with the finding that females have a higher risk of recurrence following initial episodes but not following later episodes. Reference Kessing2,Reference Kessing, Andersen and Mortensen19 Males experienced more often severe depressive episodes at the first and second contacts but at subsequent contacts no differences were found between genders. Similarly, the prevalence of severe episodes increased with age at the first five contacts, whereas no effects of age were found at subsequent contacts. We have previously in another register-based sample using ICD–8 diagnosis of depressive disorder found the same pattern in relation to recurrence: the rate of recurrence was higher for females following the first three depressive episodes, and increased with age at the first episode but not at later episodes. Reference Kessing20

Methodological considerations

Can the association between the increasing prevalence of severe depressive episodes and the number of episodes be explained by methodological considerations?

First, could poor diagnostic validity of the diagnosis of mild, moderate and severe depression play a role? In fact, a recent study of the Danish register data revealed that the categorisation in the ICD–10 of depression into mild, moderate and severe depression predicted long-term course and outcome (the risk of relapse leading to psychiatric hospitalisation and the risk of completed suicide) and thus seemed clinically useful. Reference Kessing20 Additionally, diagnostic misclassification will tend to dilute true differences and would not result in a systematic increase in severity across depressive episodes.

Second, could decreased treatment capacity with period of first contact explain the results? This did not seem to be the case as an increasing severity of episodes was found in three different periods although the severity of depressive episodes seven to ten had slightly increased in recent years (2000–2003) compared with previous years (1994–1996 and 1997–1999; Fig. DS1).

Third, could bias towards patients with a more severe course of illness explain the findings? Patients treated in psychiatric hospital settings for depression as in- or out-patients suffer from more severe depressive disorders or episodes. Bias may occur if the threshold for being treated in hospital settings for depression (as in- or out-patients) changes with the number of contacts with the healthcare system. On the one hand, it is possible that patients may not have attended secondary psychiatric care for a second or subsequent episode, particularly if this episode was mild or moderate. For example, among the sample of 19 392 patients with a diagnosis of a single depressive episode at first contact, 36.8% did not have a second psychiatric treatment contact within the hospital care setting either because they did not experience relapse/recurrence or because they were treated in a primary care setting (general practitioners or private specialists in psychiatry). On the other hand, as the number of depressive episodes increases for a given patient, it is becoming increasingly clear for the clinician, patient and relatives that the patient has a depressive disorder with a high recurrence of episodes. One may presume that the likelihood that such a patient will continue into the secondary psychiatric setting increases with the number of depressive episodes, thus resulting in an increase in the proportion of milder depressive episodes with the number of treatment contacts in the present study sample. I am unable to investigate the direction of such a possible bias, as I have no data on patients treated for depressive episodes in primary care. In summary, bias cannot be excluded as a possible explanation of the present findings.

Fourth, although the prevalence of auxiliary diagnoses increased from 17.2% at the first contact to 21.2% at the tenth, comorbidity did not explain the results, as the prevalence of an auxiliary diagnosis was inversely associated with the severity of the depressive episodes (see Results).

Finally, even though a patient should have the diagnosis of a single depressive episode according to ICD–10 only when no prior depressive episodes have occurred, it is possible that patients may have been seen in the primary healthcare setting for depression before their first contact, with psychiatric secondary care without this being made clear to the psychiatric clinician. Similarly, it cannot be excluded that some out-patients may have been seen in secondary psychiatric care before out-patients were included in the DPCRR in 1995. Although there was a wide range of age at first contact, with a quarter of the sample being younger than 33.7 years, the median of 50.8 years may suggest that some patients may have presented with depression before inclusion in the study. It is not possible to estimate how this may have affected our findings.

In conclusion, although it cannot be excluded that bias may explain part of my results, I find it hard to explain all my findings by methodological drawbacks as it was consistently found that the severity of depressive episodes increased with the number of contacts regardless of which sample was included in the analyses and the type of analyses. Besides, bias cannot be excluded in any longitudinal study investigating the association between severity of episodes and the number of episodes, as non-participation and withdrawal of patients in the long run will always occur. On the other hand, the present study has some advantages.

Advantages of the study

The study comprises an observation period of 10 years of the entire Danish population (5.3 million inhabitants), which is ethnically and socially homogeneous with a very low migration rate. All patients treated in the psychiatric hospital system in Denmark in in-patient or out-patient settings were included. Psychiatric care is well-developed in Denmark so individuals with affective disorders can easily come in contact with psychiatric community centres or hospitals. Also, as psychiatric treatment in Denmark is free of charge, the study is not biased by socio-economic differences. Together, these factors add to improve the generalisability of my findings for patients treated in hospital in- or out-patient settings in general. It should, however, be emphasised that it is possible that the findings cannot be generalised to milder forms of depressive disorders that may be treated by primary care doctors.

Interpretation of the results

The study does not include data on treatment so we cannot tell the effect of drug treatment on severity during the course of illness. In the study by Maj et al, severity was found to increase from the first to the third depressive episode among patients who received prophylactic drug treatment and among patients who did not. Reference Maj, Veltro, Pirozzi, Lobrace and Magliano16

The course of depressive disorder is progressive, with increasing risk of recurrence with the number of episodes, Reference Kessing, Hansen and Andersen3,Reference Kessing, Olsen and Andersen4 suggesting that biochemical and anatomical substrates underlying affective disorders evolve over time as a function of prior episodes, Reference Post21 leading to changes in gene expression, neuropeptides and transmitters in the hippocampus (and elsewhere) in the limbic system. Reference Post21,Reference Duman, Heninger and Nestler22 It is possible that episodes per se may change future psychopathology (sensitisation), leading to an increased severity of depressive episodes during the course of depressive illness.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.