Some structures, because of their long life, become stable elements for an infinite number of generations: they get in the way of history, hinder its flow, and in hindering it shape it. Others wear themselves out more quickly.

—Braudel Reference Braudel, Revel and Hunt1995, 122

INTRODUCTION

From Hellenic thought to present-day theorizing, scholars have postulated the significance of the middle class in affecting the balance between democracy and tyranny. Aristotle wrote about the reasonableness of the propertied, rule-abiding, enlightened strata and their role in nurturing a middle ground between oligarchy and mob rule (Glassman, Switos, and Kivisto Reference Glassman, Swatos and Kivisto1993). And in present-day autocracies, educated professionals, students, and entrepreneurs often rally behind pro-democracy protest movements, whether in Moscow or Hong Kong (Ortmann Reference Ortmann2015; Tertytchnaya and Lankina Reference Tertytchnaya and Lankina2020). Yet, we also have many examples of the democratic ambivalences, indeed authoritarian complicity, of middle classes across a variety of contexts. “Contingent,” “pragmatic,” and “dependent” are some of the epitaphs on the metaphorical tombstones charting the demise of the idea of the middle class as a harbinger of democracy (Bell Reference Bell1998; Bellin Reference Bellin2000; Chen Reference Chen2013; Foa Reference Foa2018; Greene and Robertson Reference Greene and Robertson2019). Nations with a history of state-led development and autocracies “incubating” a bloated public sector ostensibly harbor a middle class that falls particularly short of democratic expectations (Kohli Reference Kohli2007; Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2017; Wright Reference Wright2010).

While drawing inspiration from these rich debates, we take issue with their somewhat one-dimensional portrayals of the middle class (but see Baviskar and Ray Reference Baviskar and Ray2011). Contingent orientations and material dependencies on the state of course matter. But so does heterogeneity within a multitier middle class comprised of subgroups originating in distinct historical epochs and under different political regimes. Much of the recent scholarship on post-communist regimes in particular has largely neglected these longue durée aspects of the middle class. And the “great leveler” paradigms have continued to influence our thinking about the class structures of twentieth century “totalitarian” dictatorships (Piketty Reference Piketty2014; Scheidel Reference Scheidel2017). These works have underlined the wholesale destruction of the wealth of the “old” bourgeoisie in the furnaces of revolutionary repression and wars. Such assumptions are insensitive however to nonmaterial forms of social resilience. Prominent works in sociology have long argued that educational, professional, and cultural values are often transmitted within families and communities (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2010; Clark Reference Clark2015; Verba, Burns, and Schlozman Reference Verba, Burns, Schlozman and Horowitz2005; Weber Reference Weber, Bendix and Lipset1966). This could lead to the coexistence of multiple substrata of different historical origin within the middle class.

Our paper contributes to debates about the role of the bourgeoisie/middle classFootnote 1 in autocracies. We distinguish between “prongs” within this broad stratum—one prong originating within a capitalist order and another rapidly fabricated as part of state-led development. Our account departs from earlier research in that we conceptually and empirically parcel out the democratic legacies of historically distinct segments of a stratum conventionally bracketed under one generic umbrella. We make our case by leveraging within-country variation in historical legacies of Russia’s social structure. Russia’s regions have also starkly varied in the competitiveness of electoral races, vibrancy of civil society, and robustness of media scrutiny of politicians (Gel’man and Ross Reference Gel’man and Ross2010; Petrov Reference Petrov, McFaul, Petrov and Ryabov2005; Reisinger and Moraski Reference Reisinger and Moraski2017; Saikkonen Reference Saikkonen2017; Sharafutdinova Reference Sharafutdinova2011). To capture these within-nation democratic variations, we use district- and region-level measures of democratic competitiveness and media freedom. The subnational research design allows us to hold constant national-level institutional frameworks and guarantees for political contestation.

We locate the genesis of the “old” prong of the middle class, as distinct from the “new” communist-engineered one, in the intricacies of Tsarist Russia’s institution of estates. This institution survived until the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. The “four-estate paradigm” divided citizens into nobility, clergy, the urban estates of merchants and meshchane, and peasants (Mironov Reference Mironov2014). We regard the numerically sizeable meshchane as constituting the bulk of Russia’s pre-Revolutionary bourgeoisie. This designation encapsulates the material dimension of property ownership and less tangible characteristics like cultural capital and educational and professional aspirations (Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2017). Imperial Russia’s meshchane were not only prominent in trades and entrepreneurship; they increasingly colonized elite secondary schools (gymnasia), universities, and the professions. The medical doctor-turned-writer of global acclaim Anton Chekhov listed himself as meshchanin when enrolling at university; his sister taught in a gymnasium (Bartlett Reference Bartlett2004).

For our analysis, we constructed a unique historical dataset covering Russia’s entire territory. To our knowledge, we are the first to have matched Imperial districts with some 2,000 of their Soviet and present-day administrative equivalents.Footnote 2 The rich district (uezd)-level socioeconomic, occupational, and demographic statistics from the first General Population Census of 1897 (Troynitskiy Reference Troynitskiy1905) allow us to trace the correspondence between past social structure and present-day democratic variations. Individual-level data from a large author-commissioned survey carried out by Levada, Russia’s top polling agency, corroborate the robustness of associations between estate and present-day political outcomes. We also gathered archival and memoir materials illuminating the bourgeoisie’s adaptation to life in Bolshevik Russia.

Succinctly, we argue that the bourgeois estates’ legacies affect democratic processes via the (1) human capital and (2) entrepreneurial experiences and values channels. The human-capital channel takes account of the Bolsheviks’ appropriation of educated citizens as white-collar professionals. We also consider familial mechanisms of transmission of “bourgeois” values of educational attainment and aspiration for high-status professions. The entrepreneurial channel operates via societal transmission of values outside of state purview, for communist regimes ideologically vilified markets and private enterprise. Our argument takes account of the persistence of the “bourgeois” social stratum. It also considers its role in the genesis of educated and entrepreneurial population more broadly. Statistical tests confirm that the “bourgeois” legacies account for spatial variations in democratic competitiveness and media freedoms.

Our study is inspired by, and contributes to, the literature on intertemporal persistence in institutions, social structures, and values (Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001; Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Buggle and Nafziger Reference Buggle and Nafziger2019; Capoccia and Ziblatt Reference Capoccia and Ziblatt2010; Charnysh and Finkel Reference Charnysh and Finkel2017; Cirone and Van Coppenolle Reference Cirone and Coppenolle2019; Dasgupta Reference Dasgupta2018; Glaeser et al. Reference Glaeser, Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer2004; Kopstein and Reilly Reference Kopstein and Reilly1999; Lankina, Libman, and Tertytchnaya Reference Lankina, Libman and Tertytchnaya2020; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2018; Simpser, Slater, and Wittenberg Reference Simpser, Slater and Wittenberg2018; Voigtlaender and Voth Reference Voigtlaender and Voth2012). In many studies “intervening periods” between the legacy’s origin and long-term implications often remain “full of question marks” (Simpser, Slater, and Wittenberg Reference Simpser, Slater and Wittenberg2018, 421). We perform step-by-step analyses deploying data for distinct regimes, thereby illuminating transmission mechanisms in the causal chain.

Our paper is structured as follows. We first ground our theoretical assumptions in the literature on social structure and democracy. We then discuss Imperial Russia’s estates and justify the conceptualization of meshchane as a bourgeois stratum. Next, we outline the hypothesized transmission channels. We then discuss data and statistical analysis. The final section concludes with a discussion of findings and implications for wider scholarship.

SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND DEMOCRACY

Our baseline assumptions are that elements of Imperial social structure survived the Bolshevik social experiment; and that old regime bourgeois legacies have implications for post-communist democratic outcomes. We follow other scholars in defining legacy as “a durable causal relationship between past institutions and policies on subsequent practices or beliefs, long beyond the life of the regimes, institutions, and policies that gave birth to them” (Kotkin and Beissinger Reference Kotkin, Beissinger, Beissinger and Kotkin2014, 7). Social structure is here defined as a pattern of social relationships delineating social groups and built around social, economic, and cultural status (Mousnier, Labatut, and Durand Reference Mousnier, Labatut, Durand, Revel and Hunt1995).

Our analysis is inspired by classic works on the political orientations of the bourgeoisie in historical sociology (Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991; Moore Reference Moore1993); political science (Dahl Reference Dahl1971; Huntington Reference Huntington1991; Lipset Reference Lipset1959); and historical political economy (Acemoglu, Hassan, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Hassan and Robinson2011; Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2014). These research strands variously emphasize the bourgeoisie’s market-supporting values, entrepreneurial ethos, and demands to protect property rights via democratic institutions. They also draw attention to the democratic implications of educated populations sharing the values of tolerance, respect for autonomy, and a broad “normative commitment” to democracy (Herman Reference Herman2016, 254). However, numerous studies have questioned whether middle classes—and modernization processes arguably engendering this stratum—always straightforwardly covary with democracy (Dahl Reference Dahl1971; O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1973; Slater Reference Slater2010). Post-communist nations present particularly intriguing dilemmas when it comes to middle class–democracy links: they tend to be less democratic than nations with similar levels of socioeconomic development (Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Bates, Goldstone, Kristensen and Halloran2006; Herman Reference Herman2016; Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2017).

Robert Dahl (Reference Dahl1971, 73) provides a convenient heuristic for refining expectations about middle-class political orientations. He distinguishes between development that unfolds “autonomously” over a long stretch of time and one that advances rapidly in an “induced,” “centralized” or “hegemonic” fashion (see also Hoselitz Reference Hoselitz1965, 43). Across many developing settings, state-directed development has produced a middle class only weakly committed to democracy (Baviskar and Ray Reference Baviskar and Ray2011; Chen Reference Chen2013; Jones Reference Jones1998). In “induced” settings, the middle classes are often highly state dependent (Chen Reference Chen2013). Since the states take the lead in rapid industrialization to “catch up” with more developed nations (Gerschenkron Reference Gerschenkron1962), the state-dependent middle class frequently lacks experience in navigating the market (Chen Reference Chen2013), in contrast to countries where private entrepreneurship, risk taking, and generalized trust originate in, and are transmitted intergenerationally within, society (Dohmen et al. Reference Dohmen, Falk, Huffman and Sunde2012; Tabellini Reference Tabellini2008). Additionally, white-collar employees of a rapidly engineered variety are often low-status and enjoy weak occupational autonomy (Erikson and Goldthorpe Reference Erikson and Goldthorpe1992; Speier Reference Speier1986). By contrast, elite professions require lengthy specialized training and parental injunction and investment (Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu and Passeron1990; Verba, Burns, and Schlozman Reference Verba, Burns, Schlozman and Horowitz2005; Weber Reference Weber, Bendix and Lipset1966). Finally, middle classes that owe their livelihoods to autocracies may hesitate to challenge them (Chen Reference Chen2013; Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2017).

Communist countries present fertile terrains for analyzing covariance between middle-class origin and democracy. Here “peasant metropolises” (Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann1994) have featured middle classes hastily fabricated pursuant to ideological doctrine on the social elevation of peasant and proletarian masses. By 1990, Soviet urbanization had reached 66%, yet among those in the 60-years age bracket, a mere 15–17% were urban born; 40% among those aged 40; and only those aged 20 and younger featured over 50% native urbanites. “By the time of the USSR’s collapse,” writes Anatoliy Vishnevskiy, “citizens in their majority remained urbanites in the first generation” (Reference Vishnevskiy2010, 94).

Such rapid sociodemographic changes may have well engendered a “new” middle class conceptually distinguishable from the “old” one, which came into existence during the Tzarist period. We are careful not to idealize ancien régime Russia—a monarchy with incipient institutions of parliamentary democracy. But Russia had been also an “under-governed” empire with weak state penetration in peripheral districts (Mironov Reference Mironov2015, 436). It allowed for local initiative and governance—notably via the zemstvo movement (Dower et al. Reference Dower, Finkel, Gehlbach and Nafziger2018). Especially in the last few decades of the Empire, market enterprise, civil society, and private philanthropy flourished (Balzer Reference Balzer1996; Golitsyn Reference Golitsyn2016; Orlovsky Reference Orlovsky, Clowes, Kassow and West1991). This historical record is suggestive of a more “autonomous” developmental context compared with the far more “centralized” communist regime, which stifled markets, local autonomy, and civic initiative.

Our task is to parcel out the legacies of a bourgeoisie originating in a prior, more autonomous developmental order from those of middle classes fabricated in a state-planned way. This is a formidable challenge. Communist states notoriously persecuted the bourgeoisie (Alexopoulos Reference Alexopoulos2003; Dikötter Reference Dikötter2016). The urbanization figures provided above accentuate social-compositional shifts in space. Yet, even if we pause to digest Vishnevskiy’s (Reference Vishnevskiy2010) urbanization statistics, we cannot simply disregard the “old” urbanites—millions of people—coexisting with peasant entrants into the “new” middle class. Further, as recent studies have shown, the revolutionary state built upon, and in complex ways interacted with, pre-communist socioeconomic legacies (Kotkin and Beissinger Reference Kotkin, Beissinger, Beissinger and Kotkin2014; Lankina, Libman, and Obydenkova Reference Lankina, Libman and Obydenkova2016). Indeed, to an extent cultural values (Darden and Grzymala-Busse Reference Darden and Grzymala-Busse2006), partisan loyalties (Wittenberg Reference Wittenberg2006), and civic attitudes (Peisakhin Reference Peisakhin2013) survived Leninist projects. The author-assembled archival and memoir materials are suggestive of coexistence of the “new” middle class with “old” professionals, entrepreneurs, and rentier (Golitsyn Reference Golitsyn2016; Golubkov Reference Golubkov2010; Neklutin Reference Neklutin1976; Tchuikina Reference Tchuikina2006).

To capture middle-class heterogeneity based on origins, however, we ought to identify pre-communist population groups corresponding to the “bourgeoisie” designation. We now turn to motivating our choice of purported social carriers of a bourgeois legacy.

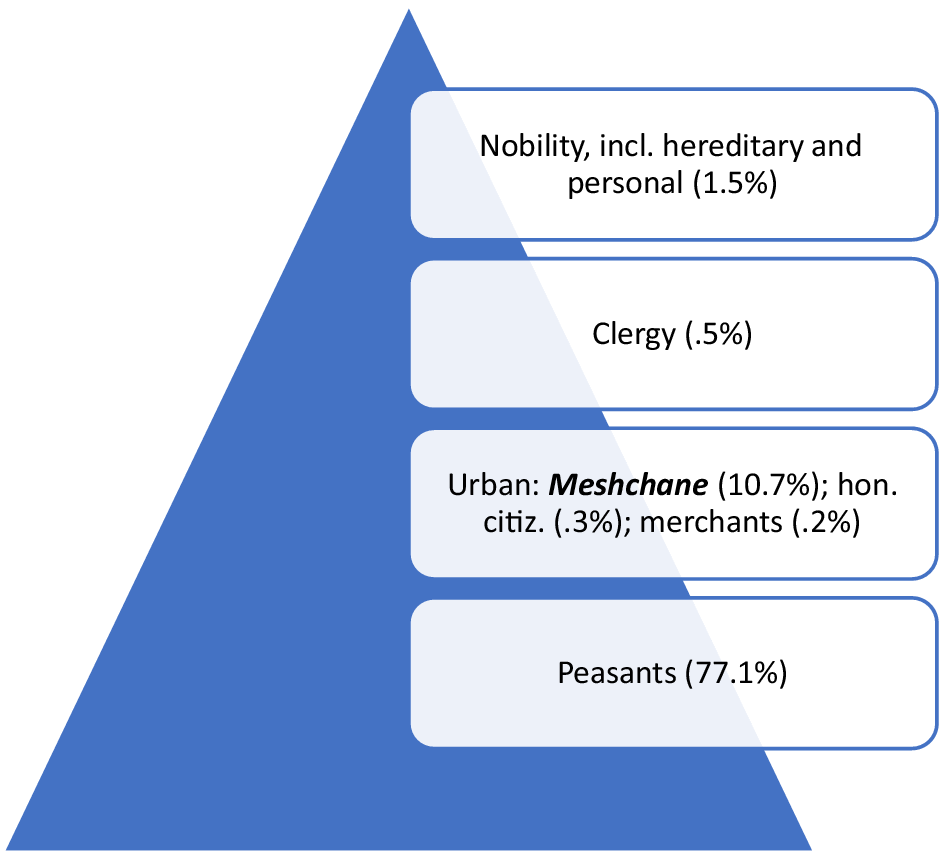

RUSSIA’S BOURGEOISIE

Until the Revolution, Russia combined features of a feudal order where individuals are divided into unequal caste-like social categories—estate (sosloviye)—with those of a modern society where at least in theory everyone possesses equal rights (Wirtschafter Reference Wirtschafter1997). The historian Boris Mironov defines estate as “a juridically circumscribed group with hereditary rights and obligations” (Reference Mironov2014, 334). The main estates in Russia were nobles, clergy, town dwellers (mostly meshchane and merchants), and peasants. Tsar Alexander II’s Great Reforms, notably peasant emancipation in 1861, accelerated the erosion of estate boundaries (Dower et al. Reference Dower, Finkel, Gehlbach and Nafziger2018; Finkel, Gehlbach, and Olsen Reference Finkel, Gehlbach and Olsen2015; Nafziger Reference Nafziger2011). Nevertheless, “the four-estate” paradigm remained an important social and juridical concept (Freeze Reference Freeze1986; Mironov Reference Mironov2014, 339). It influenced property rights, human capital, educational aspirations, and occupational choices. The overwhelmingly illiterate manorial peasants remained the most disadvantaged groups even after emancipation (Mironov Reference Mironov2014; Wirtschafter Reference Wirtschafter1997). Figure 1 helps visualize Russia’s estate structure.

Figure 1. Imperial Russia’s Four Key Estates

Note: Image created by authors; Empire-wide 1897 census data.

After the Revolution, a wide range of groups were bracketed as “bourgeois”—from aristocracy to petty tradesmen (Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick1993). The aristocracy, clergy, merchants, and meshchane boasted comparatively high education and literacy rates; they constituted the bulk of early Soviet intelligentsia. The aristocracy became the target of particularly vicious witch hunts (Alexopoulos Reference Alexopoulos2003). Aristocrats were also unlikely carriers of entrepreneurial legacy. Memoirs in the genre of “survival” chronicling the lives of fallen aristocrats corroborate either habitual disdain for entrepreneurship or inability to engage in market pursuits when opportunities briefly opened during the New Economic Policy (NEP) in the 1920s (Golitsyn Reference Golitsyn2016). The other high-human-capital stratum of clergy were not only subjected to restrictions on private enterprise under the Tzars (Mironov Reference Mironov2015, 45) but also targeted for repressions under the Bolsheviks. Because of low social status of clergy families in the Imperial era, many youths from this estate embraced radical left movements (Mironov Reference Mironov2014, 377). Merchants most closely approximated the twin bourgeois characteristics of interest to us—high human capital and entrepreneurship. Unlike meshchane, often characterized as petite bourgeoisie or lower middle class, a merchant title signified considerable material wealth (Rieber Reference Rieber1982). Furthermore, merchants were heavily investing in their children’s education. Wealth and modern education in turn enabled both private enterprise and professional employment (Neklutin Reference Neklutin1976). Yet, like aristocrats, merchants constituted a tiny fraction of the population—less than 1%. Because many merchants carried prominent names, they were visible targets for persecution.

Overall, meshchane possessed the twin characteristics that interest us. They were a high-human-capital stratum with market experience. They were also the most numerous estate after peasants and were far less conspicuous as class witch hunts unfolded. We consider meshchane as engendering a bourgeois legacy because of their legal status, property rights, and opportunities for accumulation of material and human capital. Until the beginning of the eighteenth century, all estates, including nobles, lacked clearly defined legal rights and freedoms (Mironov Reference Mironov2015, 38). Nobles and clergymen were the first to obtain protections against arbitrary crown rule, followed by the wealthiest urban stratum of merchants. After a time lag, meshchane also obtained special privileges. The Russian Empress of German origin Catherine the Great saw merchants, artisans, and meshchane as European-style civilized, law-abiding, and tax-paying burghers (Smith Reference Smith2014). She therefore granted urban estates a special charter in 1785 that enhanced their privileges vis-à-vis the unfree estate of peasants and others who wished to own property, pursue trade, or reside in towns. Tellingly, the 1897 census, which contains French translations of estates, lists only one group—meshchane—as bourgeois de ville—“bourgeois of city” (Troynitskiy Reference Troynitskiy1905). The addition of “bourgeois” next to “de ville” signifies meshchane’s distinction from peasants in towns: seasonal and other peasant laborers in some cities constituted half the population.

Much like with the emergence of burghers elsewhere in Europe, a combination of factors shaped the spatial distribution of town dwellers engaged in nonagricultural occupations. In some territories, peasants were granted state peasant status, which came with greater freedoms as compared with those of serfs on gentry manors; this status eased transition into commercial occupations in towns. Elsewhere, as in the Pale of Settlement, some communities like Jews faced restrictions on rural residence or occupations. An advantageous geographic location or poor soil quality also spurred commerce and artisan trades, facilitating peasants’ accumulation of capital and acquisition of a foothold in towns. As towns grew, they became magnets for “social deviants”—adventurous peasants escaping the manor or rural entrepreneurs with sufficient literacy, skills, and capital to move to towns (Lankina Reference LankinaForthcoming).

Yet, while estate to some extent reflected society, as an institution it also shaped social stratification. Urban burghers were granted special rights to trade, commerce, and property ownership within cities and legal protections, while peasants lacked the same kinds of rights (Mironov Reference Mironov2015). Urban self-governance and autonomy helped safeguard these rights. We acknowledge that all estates—including serfs—enjoyed some form of self-governance even at the height of absolutism, not least because there were too few state functionaries to micromanage localities in the Empire’s vast reaches. The difference is that some, like nobles, clergy, and merchants obtained the status of free citizens with more substantive autonomy to govern their estate and localities early on, followed by meshchane and manorial peasants—with a lag of nearly one hundred years after meshchane. As Mironov notes, “the trading-industrial population of cities, more than any other social group of Russian society, understood the importance of individual rights for successful economic activity in the sphere of commerce, artisan pursuits and industry.” It therefore fought tooth and nail to curb state expropriations of urban property, demanded respect for private property, and secured the establishment of special estate courts governed by law (Reference Mironov2015, 47). By the end of the eighteenth century, urban communes of elected burghers had acquired juridical person status, while the state peasants’ communes obtained these rights in the 1840s and manorial peasants—only in the 1860s (Mironov Reference Mironov2015, 249).

Thus, early on, burghers were able to rely on the letter of the law to fight random infractions against property. Although merchants enjoyed greater legal rights and protections than meshchane, any meshchanin could become a merchant by accumulating wealth. Furthermore, “consolidation of right to private property provided a stimulus for property accumulation without fear that it might be at any moment confiscated by the state” (Mironov Reference Mironov2015, 50). Even after the promulgation of peasant freedoms, the urban bourgeoisie were able to consolidate their hold on urban assets, enterprises, and trade, disadvantaging peasant newcomers. Meshchane’s corporate bodies engaged in selection and inclusion based on criteria of “moral worth” and creditworthiness. Certificates vouching for newcomers’ credentials were solicited, and burghers sought to keep destitute, property-less peasants out of towns (Smith Reference Smith2014). Because Imperial Russia failed to set up universal public schooling, well-off burghers enjoyed early-riser advantages in the educational marketplace. They could afford paid-for instruction in classical and professional-technical schools, and many obtained university degrees.

We could trace the fortunes of meshchane if we compare accounts focusing on the early nineteenth century and those closer to the end of the monarchy. In the earlier period, many meshchane reportedly engaged in both urban trades and quasi-rural pursuits of raising livestock and crops (Hildermeier Reference Hildermeier1985). Accounts covering the later period provide strong evidence of commercialization, professionalization, and social elevation of meshchane; many attained merchant or “honored citizen” status. Census records corroborate the meshchane’s stature as a propertied petit or middling bourgeois of an “industrious society” (de Vries Reference de Vries2008) variety. Significant chunks were “employers of labor,” running a “one person enterprise” and “employers using only family members” (Orlovsky Reference Orlovsky, Clowes, Kassow and West1991, 251–2). Many were rentier—renting out a “corner” or room to students, professionals, and peasant seasonal laborers (Dolgopyatov Reference Dolgopyatov2009; Koshman Reference Koshman2016). Meshchane also worked as pharmacists, bookkeepers, statisticians, middle managers, free professionals, and teachers (Hildermeier Reference Hildermeier1985; Kobozeva Reference Kobozeva2013; Orlovsky Reference Orlovsky, Clowes, Kassow and West1991).

Tellingly, the meshchane acquired a solid footing in Soviet-era scholarship as the “bourgeoisie.” Lenin, who set the tone for subsequent ideologically charged discourse on the meshchane, peppered his writings with their characterizations “in a political-economic meaning of this term” as “a petty producer operating under systems of market production” (Lenin [1895] Reference Lenin1967). A 1920s Soviet encyclopedia equated “meshchanin” to “small bourgeoisie in the West.” Throughout the Soviet decades, ideological struggles against meshchanstvo waxed and waned, usually coinciding with the regime’s battle against the “capitalistic processes” of the shadow market economy (Akkuratov Reference Akkuratov2002).

TRANSMISSION MECHANISMS

We have highlighted three features of meshchanstvo’s legacy: a combination of market-supporting pursuits, comparatively high human capital, and experiences of autonomous governance. How did these legacies survive across multiple generations in a regime ideologically hostile to the old bourgeoisie? We identify two key mechanisms of transmission: familial socialization and processes at the juncture of societal values and state policy.

Familial Channels of Human Capital and Value Transmission

We derive our first transmission mechanism from theories of the family’s imprint on human, cultural, social, and economic capital (Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu and Passeron1990; Coleman Reference Coleman1988; Verba, Burns, and Schlozman Reference Verba, Burns, Schlozman and Horowitz2005). This channel has been restated in numerous studies of communist societies (Bessudnov Reference Bessudnov, Bernardi and Ballarino2016; Gerber and Hout Reference Gerber and Hout1995; Shkaratan and Yastrebov Reference Shkaratan and Yastrebov2011; Shubkin et al. Reference Shubkin, Artemov, Moskalenko, Buzukova and Kalmyk1968a; Teckenberg Reference Teckenberg1981/1982). High human and cultural capital often drive self-selection into “deliberative,” as distinct from “executive” employment sites—academia, medicine, or the arts (Sorokin Reference Sorokin1927, 116). In communist countries, these provided a modicum of professional autonomy, were least saturated with ideology, or featured lax party membership criteria (Mark Reference Mark2005; Rigby Reference Rigby1968; Szelényi Reference Szelényi1988). The state-engineered middle class—including the illiterate or semiliterate peasants and factory workers who enjoyed preferential quotas in university admissions and employment—were not as well positioned to ascend into high-status autonomous professions (Shubkin et al. Reference Shubkin, Artemov, Moskalenko, Buzukova and Kalmyk1968b). Stalled or reverse mobility was common in communist countries (Erikson and Goldthorpe Reference Erikson and Goldthorpe1992; Gerber and Hout Reference Gerber and Hout1995; Shubkin et al. Reference Shubkin, Artemov, Moskalenko, Buzukova and Kalmyk1968a). The less-privileged groups also stood to lose more during market transition (Gerber and Hout Reference Gerber and Hout2004). We expect territories with a greater share of old bourgeoisie to sustain higher levels of human capital, which would spill over into relatively autonomous professions, as compared with those where the new state-engineered middle class predominated.

We conjecture that familial socialization would also account for the transmission of market values. Entrepreneurship flourished as soon as restrictions for the operation of markets were loosened from 1922 to 1928 during NEP (Osokina Reference Osokina2001). Many “nepmen” who seized business opportunities had been entrepreneurs in the past. Revisionist historiography and data from the “lost” 1937 census (Zhiromskaya, Kiselyov, and Polyakov Reference Zhiromskaya, Kiselyov and Polyakov1996) highlight the pervasiveness of the black market even at the height of Stalinism (Edele Reference Edele2011; Osokina Reference Osokina2001). We therefore expect territories with a comparatively large pre-Revolutionary bourgeoisie to feature workforce that is more willing to embrace private enterprise.

The State Reinforcing Social Inequalities by Leveraging Skills of Educated Groups

In articulating our second transmission channel, we are sensitive to the regime’s role in exacerbating extant social stratification. In Pierre Bourdieu’s work, for instance, the state emerges as an unwitting accomplice to inequalities in that school curricula and elite civil service jobs favor those from middle class backgrounds (Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu and Passeron1990). Across a variety of contexts, the imperatives of development or state consolidation have incentivized rulers to co-opt the educated elite and middle classes (Fabbe Reference Fabbe2019; Kohli Reference Kohli2007; Mamdani Reference Mamdani1997). In communist systems too, class vigilance often went hand in hand with perks for the old bourgeoisie. Lenin, a “fervent egalitarian” (Matthews Reference Matthews1978, 20), performed a volte-face on class when it became evident that rapid modernization would not be achieved relying on peasant and proletarian cadre alone. The “hardware”—Imperial schools, hospitals, universities—were also appropriated to serve the Bolsheviks’ developmental agenda (Lankina, Libman, and Obydenkova Reference Lankina, Libman and Obydenkova2016). The appropriations of extant facilities likely accentuated the social distinction between newer urban hubs and older conurbations with established bourgeoisie.

HYPOTHESES

We conjecture that a combination of factors would account for the hypothesized covariance between the bourgeois legacy and long-term political outcomes. First, we expect bourgeois legacies to engender a more discerning, politically informed, and engaged citizenry. Following recent critiques of the modernization paradigm (Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2017), we consider occupational structure as an important intermediating channel linking human capital to political outcomes. The lower-skilled state-dependent workforce is more vulnerable than are skilled professionals to political pressures and workplace mobilization (Frye, Reuter, and Szakonyi Reference Frye, Reuter and Szakonyi2014; Hale Reference Hale2015; Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2017; Stokes Reference Stokes, Boix and Stokes2007). Relatedly, territories with a robust legacy of old bourgeoisie would feature a workforce able to diversify the portfolio of employment options beyond the public sector. Our main hypothesis therefore postulates covariance between the “old” middle class and democratic outcomes. (We discuss our operationalizations and measures of democracy below). Two supplementary hypotheses are also proposed with reference to transmission mechanisms. (See also Figure 2).

Figure 2. Logic of the Argument

H1: Pre-communist bourgeoisie is positively correlated with democratic outcomes over and above the effects of Soviet modernization.

H2: Pre-communist bourgeoisie is positively correlated with education in communist and post-communist Russia.

H3: Pre-communist bourgeoisie is positively correlated with post-communist private sector employment, professional workforce, and entrepreneurship.

DATA, SOURCES, AND KEY MEASURES

District Data and Matching

To ascertain the democratic legacies of Tsarist social structure via the human capital and entrepreneurial value-transmission channels, we rely on a within-nation research design and employ subnational data. This approach helps improve identification via reduction of unobserved heterogeneity associated with cross-country variation in historical modernization patterns. The 1897 census contains detailed data for uezdy (districts), the administrative unit below the gubernii (regional) level roughly corresponding to present-day rayony and usually encompassing a major town and surrounding rural areas. We only include districts that are administratively part of Russia now, which comes to 423 observations in the Imperial period dataset. The dataset combining pre-Soviet, Soviet, and post-communist data has about 2,000 observations, reflecting administrative reorganizations over time. We exclude Moscow and St. Petersburg cities as outliers. Details of district matching are available in the Statistical Appendix (SA) 1.1.Footnote 3 Higher-level regions (oblast, kray, republic) and survey data are employed to test some of the hypotheses (Further details in SA2).

Motivating the Choice of Democracy Measures

We draw on Dahl’s Polyarchy to motivate our choice of the dimensions and operationalizations of the key outcome variable. Dahl’s baseline condition for a democratic political system is institutional guarantees for citizens to be able to formulate and signify heterogenous preferences and to have them “weighted equally in conduct of government” (Reference Dahl1971, 3). These guarantees include right to vote, right of political leaders to compete for support, availability of alternative sources of information, and free and fair elections. But democracy is meaningless unless institutional guarantees are honored in practice. Citizens may enjoy the right to vote, elections held regularly, and freedom of expression enshrined in the constitution, but ballot-stuffing may be rampant, journalists harassed, and chunks of the electorate uninformed and indifferent to these injustices. Furthermore, Dahl raises the possibility that the practice of democracy may vary across a country’s subnational units. Whether institutional guarantees are provided or not, “social characteristics” like a weak middle class, low levels of educational attainment, and “an authoritarian political culture” may hinder competitive politics (Reference Dahl1971, 74). Dahl therefore captures both the supply side of democratic institutions, as enshrined in laws, and the demand side of a populace able to take full advantage of the right to signify preferences and to hold politicians to account.

Our subnational research design allows us to hold constant national-level institutional frameworks governing these rights while teasing out subnational variations in the actual practice of democratic contestation. But even for the national, let alone subnational, level, operationalizing and measuring the various aspects of citizen opportunity and agency in the electoral arena presents notorious challenges. Fortunately, there are measures of some of the key aspects of the democratic process that have been validated in different subnational settings. We believe these measures help evaluate three important facets of Dahl’s ideal-type democratic system: the extent to which citizens exercise their right to vote in free and fair elections and thereby are able and willing to hold politicians to account, the extent to which political leaders can compete for support, and freedom of expression/availability of alternative sources of information. We bracket the electoral dimensions under the rubric of “democratic competitiveness” and availability of information as “media freedom.”

Democratic Competitiveness

To evaluate the competitiveness aspects of democratic process, we draw on measures of electoral participation and competition deployed in earlier studies (Petrov Reference Petrov, McFaul, Petrov and Ryabov2005; Saikkonen Reference Saikkonen2017). One such measure is effective number of candidates (ENC): it captures the degree to which citizen preference heterogeneity is reflected in votes for candidates in a competitive race. Higher ENC implies that a larger number of contestants received a sizable share of votes. This indicator, however, may overestimate electoral contestation where voter participation is modest and where a large measure of effective number of candidates could emerge accidentally. One way to deal with this issue is to deploy the more generic index of democratic competitiveness (IDC). Although this simple formula (Vanhanen Reference Vanhanen2000) was developed to gauge national-level democratic variations, several studies have validated it at the level of subnational politics in contexts as diverse as India and Ukraine (Beer and Mitchell Reference Beer and Mitchell2006; Lankina and Libman Reference Lankina and Libman2019). The index is based on two indicators: participation (electoral turnout) and competition (vote share for a candidate except those with the highest share of votes). The index allows us to gauge the extent to which a single political actor is dominant while also considering the level of citizen turnout in elections. This index is a sound way of capturing the reality of manipulated and controlled elections in present-day autocracies. Consider a scenario where local political bosses and enterprises are instrumental in mobilizing docile, dependent, or poorly educated electorates, thereby driving high turnout, but for a specific candidate only. We would have high turnout, but the index value would be still small because the share of nonwinning candidates would be modest.

We are upfront about potential issues with applying the ENC and IDC measures to the subnational level. In small jurisdictions, low values on indicators of democratic competitiveness could reflect strong partisan preferences. In the US, in some “red” or “blue” districts individual candidates dominate elections for decades. Here low IDC and ENC may signal strong partisan loyalties. Unlike the US or other developed nations featuring relatively stable geographic patterns of electoral preferences, or countries like Ukraine with strong identity-based preference polarization, since the 1990s, Russia has featured volatility in citizen party-candidate preferences (Gehlbach Reference Gehlbach2000; Menyashev Reference Menyashev2011). We therefore regard the Vanhanen measure as a suitable proxy for subnational competitiveness.

Media Freedom

Another key dimension of the democratic process that we could measure relates to freedom of expression/availability of alternative sources of information. Following Dahl, we expect citizens to make informed choices about political candidates when contestants can freely distribute information about their platforms—in independent press outlets, TV channels, or online media—and individuals have access to this information. We have at hand the 1999 Russian regional press freedom index developed by the Institute of Public Expertise (IPE). The index measures freedom of access to information, ease of news production, and distribution. These region-level data also nicely complement the district-level electoral competitiveness data. Consider the possibility that some candidates in an election could garner an overwhelming share of the vote because of broad-based support rather than lack of political competition per se. Establishing that the meshchane legacy is correlated with complementary proxies of democratic variations like media pluralism even under such a scenario would provide greater confidence that we are not simply capturing the extent of preference heterogeneity.

DATA ANALYSIS

Democratic Competitiveness: District-Level Analysis

We begin by testing whether our hypothesized association between the “old” bourgeoisie and post-communist subnational political variations holds (H1). To capture rayon-level variations in democratic competitiveness, we employ data from the first round of the 1996 presidential contest. Despite noted electoral irregularities, it is considered more competitive than subsequent electoral races (Hale Reference Hale2003; Reisinger and Moraski Reference Reisinger and Moraski2017).

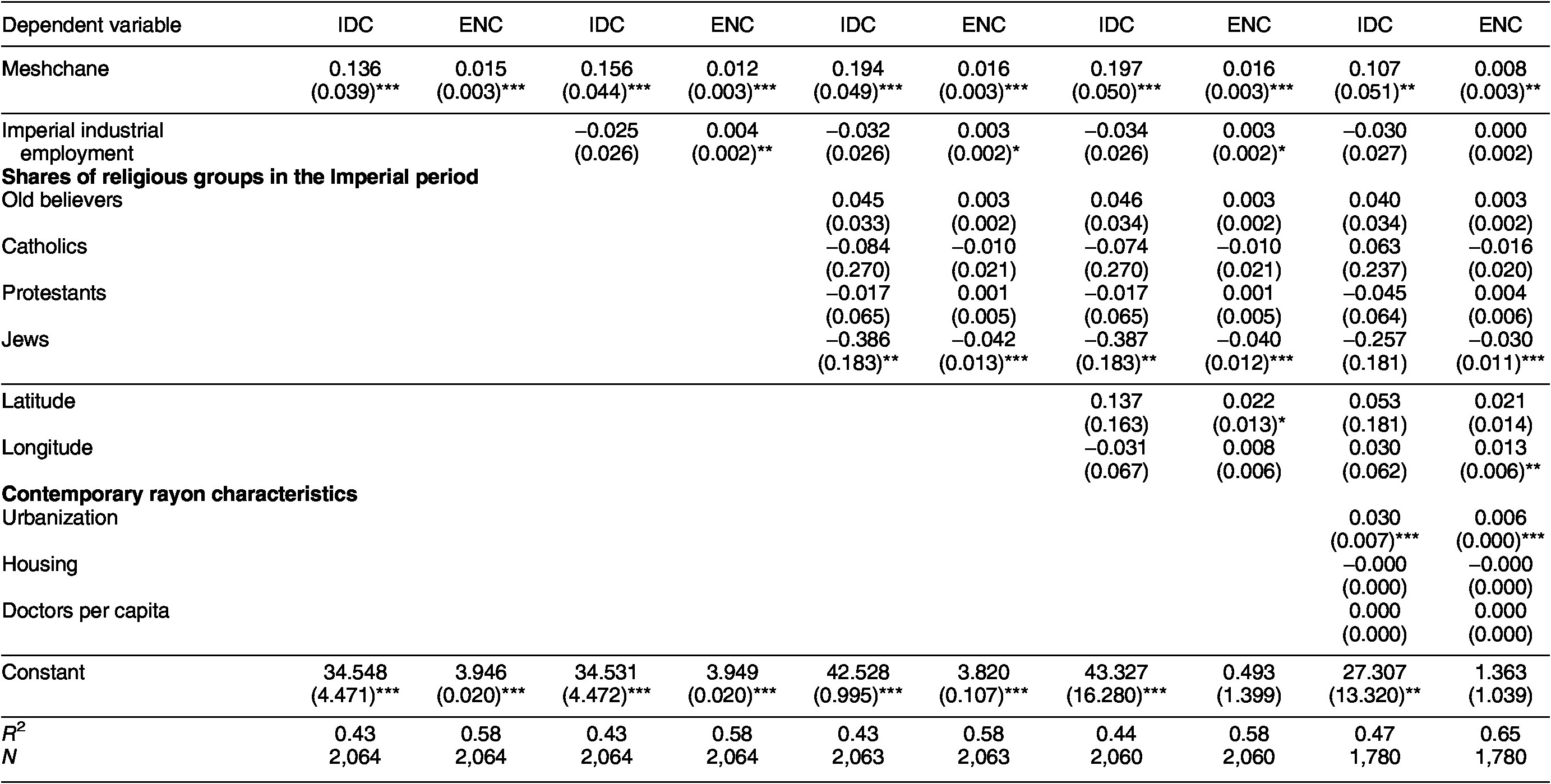

Table 1 reports the correlations between meshchane and our two democratic competitiveness proxies, conditional on other rayon characteristics. In the district-level analysis, all regressions include oblast fixed effects to reduce the effects of unobserved heterogeneity. We start by estimating a reduced-form regression, including only fixed effects, to avoid over-control bias (Lenz and Sahn Reference Lenz and Sahn2020). Because this model may miss important confounders, in the next step we add controls capturing historical economic development and industrialization, ethno-linguistic legacies, geographic location, and contemporary wealth and development (discussed in detail in SA3.1).

Table 1. Meshchane and Democratic Competitiveness in 1996

Note: The table reports correlations between the historical share of meshchane and democratic competitiveness (ENC and IDC) in the 1996 presidential elections. The unit of observation is rayon. Individual columns correspond to regressions with different dependent variables and with different sets of controls. Robust standard errors in parentheses. All regressions control for oblast fixed effects. Regressions estimated using OLS. The Oster delta for regressions in the first two columns is equal to 0.85 and 2.025, respectively (thus, it exceeds the threshold set by Oster for ENC and is below this threshold for IDC).

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Regardless of the model, meshchane are associated with higher democratic competitiveness. Thus, a rayon with 30% of meshchane compared with one with no meshchane would have 0.45 more effective candidates—in 1996 the average was 3.32, and 5.96 the rayon maximum. Cross-sectional regressions of course do not fully eliminate omitted variable bias. We therefore introduce a battery of controls and robustness checks in SA, adding multiple further controls (Dower et al. Reference Dower, Finkel, Gehlbach and Nafziger2018; Zhukov and Talibova Reference Zhukov and Talibova2018) and additional modifications to our regressions (SA3.1, SA3.3–3.7), and trace the meshchane effect over time using multiple quantitative indicators and qualitative characteristics of meshchane in the Historical Appendix (HA.III, Tables 3–5).

In a further check reported in SA3.8, we employ data for the 1995 parliamentary elections. The elections exhibited extremely high levels of political fragmentation, with 43 parties running. The results fully confirm our findings. In SA3.9, we analyze the 2012 presidential race coinciding with authoritarian consolidation. Although we find some evidence of meshchane legacy, it is weaker and less robust. We interpret this result with reference to consolidated authoritarianism. A decrease in electoral integrity may incentivize “deliberate disengagement” among educated strata (Croke et al. Reference Croke, Grossman, Larreguy and Marshall2016). In SA3.10 and SA3.22 we compare the influence of “new” and “old” middle classes on competitiveness.

Media Freedom: Region-Level Analysis

We now deploy the 1999 IPE regional press freedom index. Higher index values correspond to higher press freedoms. We find that the index is positively correlated with meshchane (Table 2). The results hold if we regress the media score on meshchane controlling for predictors of subnational democratic competitiveness conventionally employed in the literature on Russia’s regions (SA3.1) and when excluding five regions with the largest share of meshchane to deal with outliers (further robustness checks and discussion in SA3.10–SA3.11). An increase in the share of meshchane by 1 percentage point increases the press freedom index by about 0.006–0.011 units, with the index varying between 0.101 and 0.631. An increase in the meshchane share of 10 percentage points produces, depending on specification, an increase in the press freedom index of 1 standard deviation. Overall, the results reaffirm our interpretation of baseline findings as evidence of political competitiveness rather than regional electorates’ specific political preferences.

Table 2. Meshchane and Media Independence in 1999

Note: The table reports correlations between the historical share of meshchane and media freedom index in 1999. The unit of observation is region. Individual columns correspond to regressions with different sets of controls. Robust standard errors in parentheses. Regressions estimated using OLS. The Oster delta for the regression (3) is 0.504 and thus below the threshold.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Testing Mechanisms: Education

Having demonstrated the importance of the meshchane legacy for democratic competitiveness, we now test our first hypothesized transmission mechanism, education (H2). Specifically, we ascertain whether meshchane covary with Imperial education proxies and whether historical education is in turn a predictor of contemporary education levels. To explain human capital persistence, we also deploy Soviet-period statistics capturing regional occupational and educational structure and test whether it covaries with meshchane.

Meshchane and Persistence in Education

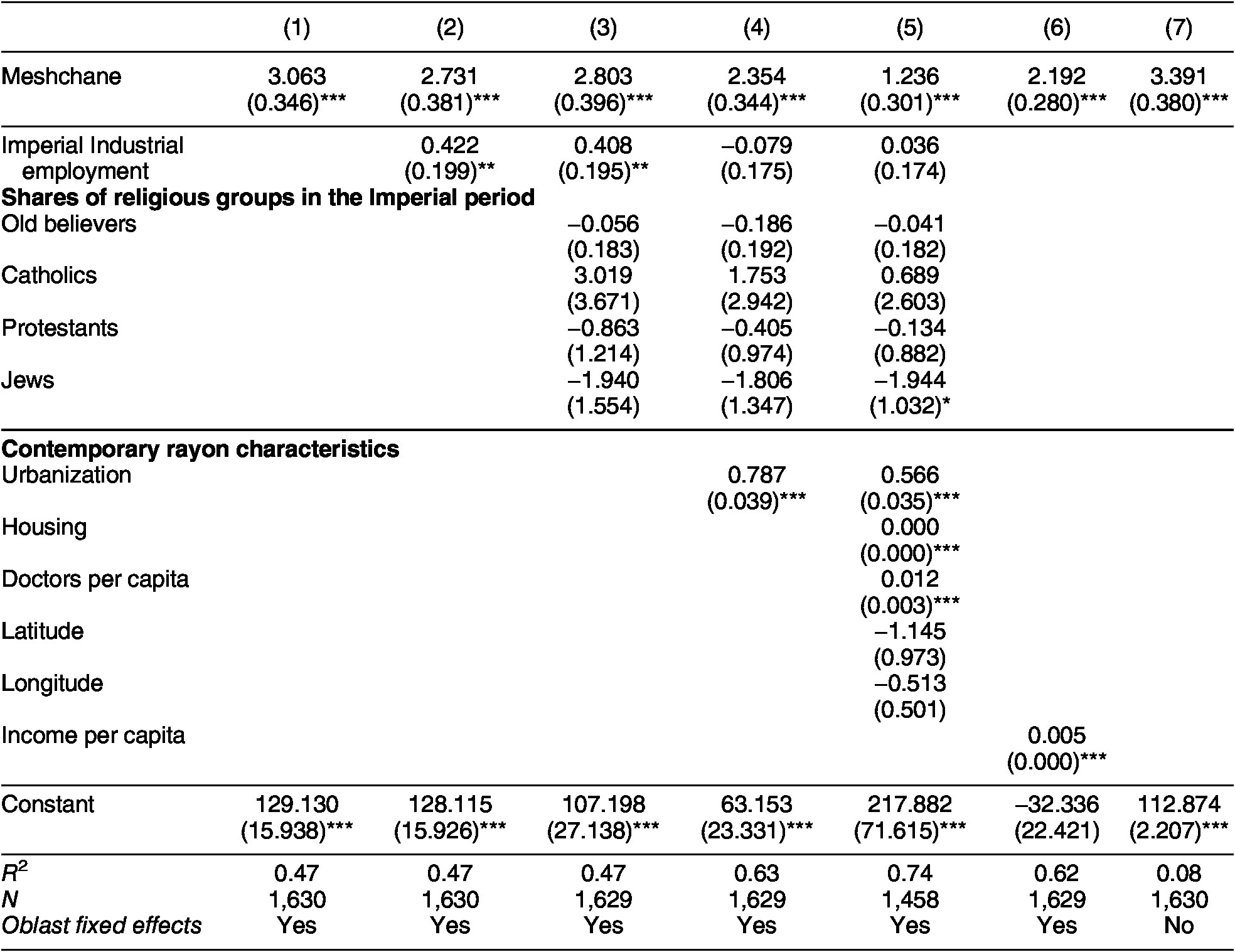

Our key outcome variable here is university attainment, a plausible proxy of human capital considering that the USSR boasted virtually universal literacy by the 1950s. Despite impressive strides in educational development, university degrees remained out of reach to most citizens. In 1979, only 5.55% of Soviet population aged 10 and older had a complete or incomplete university education.Footnote 4 Although it expanded considerably in post-communist Russia, among those 15 and older only 16.2% and 23.4%, in 2002 and 2010, respectively, obtained a university education.Footnote 5 Our measure of university attainment is rayon citizens with university degrees per 1,000 people (SA3.12 reports the oblast-level analysis). Table 3 shows that a 1-percentage-point increase in the share of meshchane leads to increase in rayon university degree holders by approximately 0.3 points. The average share of rayon degree holders is 13% (see also SA3.13 and SA3.14).Footnote 6

Table 3. Meshchane and Contemporary Education Levels

Note: The table reports correlations between the historical share of meshchane and education levels (number of rayon inhabitants with university degree per 1,000 people). The unit of observation is rayon. Individual columns correspond to regressions with different sets of controls. Robust standard errors in parentheses. Regressions estimated using OLS. The Oster delta for regressions in the column is equal to 1.11 and thus slightly exceeds the threshold.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Furthermore, meshchane are positively correlated with historical literacy rates (correlation coefficient of 0.432), the best proxy for Imperial human capital absent systematic Russia-wide data on schooling and tertiary education. Literacy, in turn, is positively and significantly correlated with contemporary university education (correlation coefficient 0.331) and is itself a significant predictor of competitiveness (for further analysis, see SA3.13–SA3.16).

Meshchane and Persistence in Education-Intensive Employment

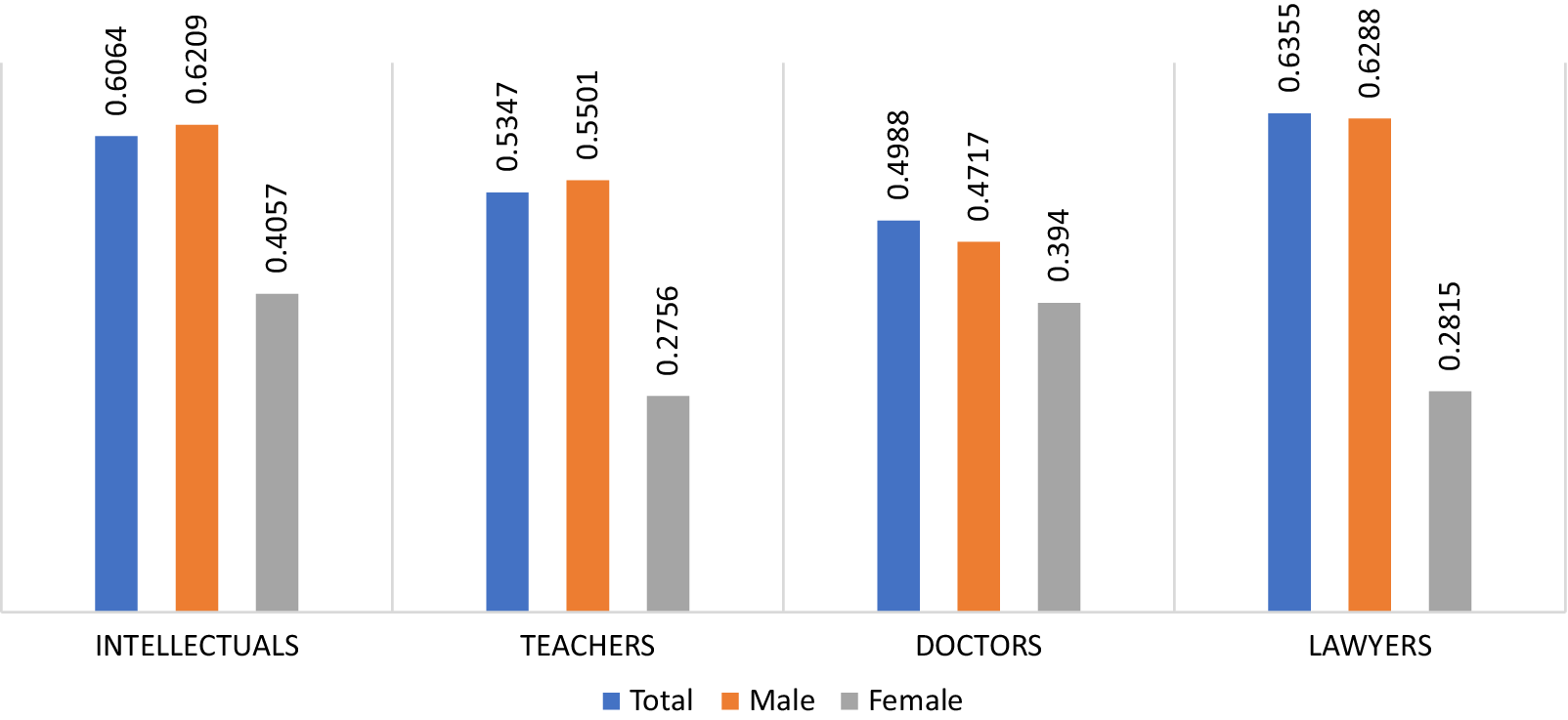

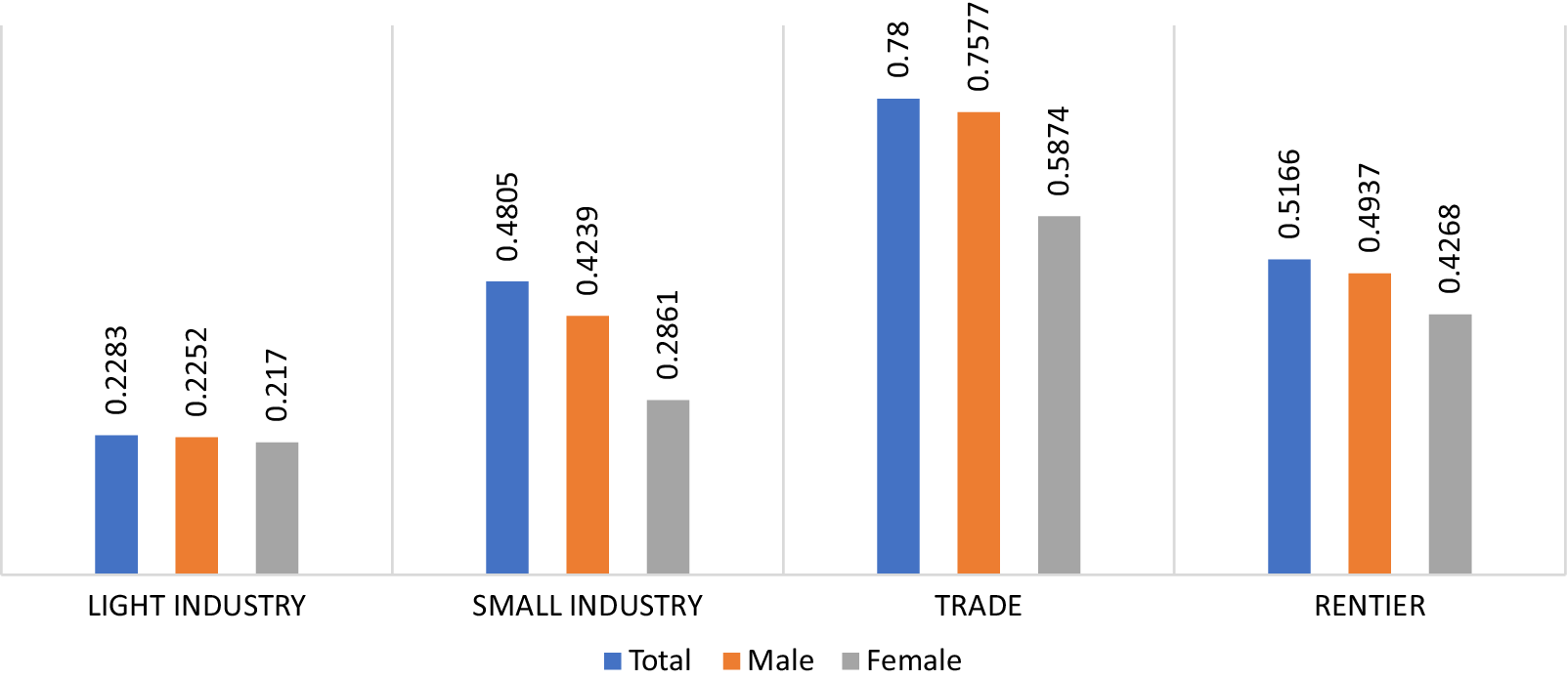

Next, we ascertain the links between Imperial human capital and Imperial and Soviet occupational structure employing additional author-assembled data. New historical accounts and memoirs are strongly suggestive of professionalization of meshchane in Tzarist Russia (HA.II). We therefore test for covariance between meshchane and “bourgeois” white-collar occupations. Deploying 1897 census data, we identify the occupational categories of health care, education, and research as reasonable proxies of white-collar professions requiring specialized skills beyond basic literacy and numeracy. This is precisely the skills set that the Bolsheviks drew on as they developed essential public services and rapidly industrialized. We find highly significant correlations between meshchane and white-collar occupations in uezd-level employment in 1897. Figure 3 plots the correlation coefficients for various occupations and separately for the total labor force, male and female.

Figure 3. Correlation Coefficients between Meshchane Share and Shares of Specific Occupational Groups in Total Regional Employment

Note: “Intellectual” occupations encompass health care, education, and research; doctors—all categories of health care employment, including nurses.

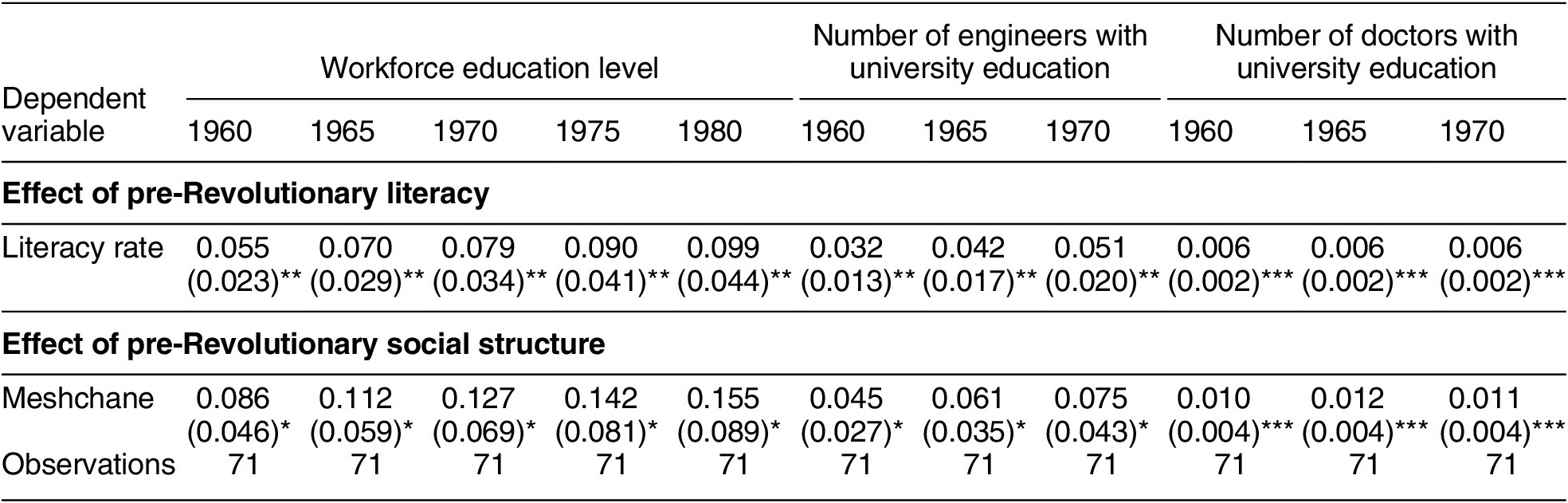

We now trace correspondence between Imperial social structure and Soviet skills-intensive occupations, namely engineering and medicine. Absent rayon-level education data, we gathered oblast statistics for 1960–1980 (percentage of employees with university degrees in regional populations) and for number of university-educated engineers and doctors in 1960, 1965, and 1970, the last year for which data are available (thousands of people). Table 4 shows that both Imperial era literacy and share of meshchane are strong predictors of Soviet-period high-skilled workforce. A 10-percentage-point increase in meshchane boosts the regional population share of educated labor force in 1980 by 1% (the regional mean is 4.2%). (See also HA Tables 6–7).

Table 4. Pre-Communist Literacy/Social Structure and Communist-Period Education/Social Structure

Note: The table summarizes results of two sets of regressions, all controlling for ethnic regions (autonomous republics) and distance from Moscow. Effects of control variables suppressed. The first set of regressions reports the correlations between Imperial-period literacy rates and communist-period education levels (shares of employees with university degree) and number of engineers and doctors with university degrees. The second set of regressions correlates the historical share of meshchane with communist-era characteristics. The unit of observation is region. Individual columns correspond to regressions with different dependent variables. Robust standard errors in parentheses. Regressions estimated using OLS.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Meshchane and Soviet Educational Infrastructure

As noted above, our narrative is sensitive to both familial channels of human capital transmission and state policy perpetuating social structure. We therefore examine covariance between the “old” bourgeoisie and location of Soviet-period skills-intensive infrastructures like higher educational institutions. Contrary to the USSR-propagated myth about the de novo origin of Soviet educational achievements, many of Russia’s top universities had been established before the Bolsheviks took power (SA3.17). We also establish covariance between Imperial social structure and location of specially designated “closed cities” where leading engineers, scientists, and other professionals labored in space, weapons production, and other high-tech industries (SA3.18). Finally, we link penal labor that the state used to effect rapid development to Imperial social structure. While the Gulag notoriously exploited inmates for break-back manual work, recent evidence points to strategic and selective exploitation of skilled professionals in sensitive industries within the “archipelago” (Khlevniuk Reference Khlevniuk2015). We demonstrate covariance between these variables and pre-Revolutionary concentration of “educated estates” and, specifically, meshchane (SA3.19).

Testing Mechanisms: Entrepreneurial Values

Meshchane and Imperial Entrepreneurship

We now test H3 concerning entrepreneurship, our twin facet of bourgeois legacy, something more straightforwardly traced to “old” middle-class values than specialized training. While the Bolsheviks eagerly promoted mass education, they were keen to obliterate the vestiges of private enterprise. Entrepreneurship in our analysis is also conceptually linked to the education aspect of the legacy, however, in that it helps broaden employment opportunities beyond public sector jobs. Generally in present-day autocracies, proprietors of businesses are reportedly more supportive of democracy than citizens who owe their livelihoods to the state (Chen Reference Chen2013). To begin to tease out the meshchane’s entrepreneurial legacy, we again turn to the 1897 census and analyze the covariance between meshchane and trade, entrepreneurial, and rentier pursuits. We find strong and significant correlations between these social-structure and occupational variables. Figure 4 reports the correlations between meshchane and trade-sector employment, share of rentier receiving income from capital as their main source of earnings, and share of employees in small-scale and light industries. For the trade and rentier measures, the correlation is particularly strong.

Figure 4. Correlation Coefficients between Share of Meshchane and Share of Specific Occupational Groups in Total Regional Employment, 1897

Persistence of Legacies through the Soviet Period

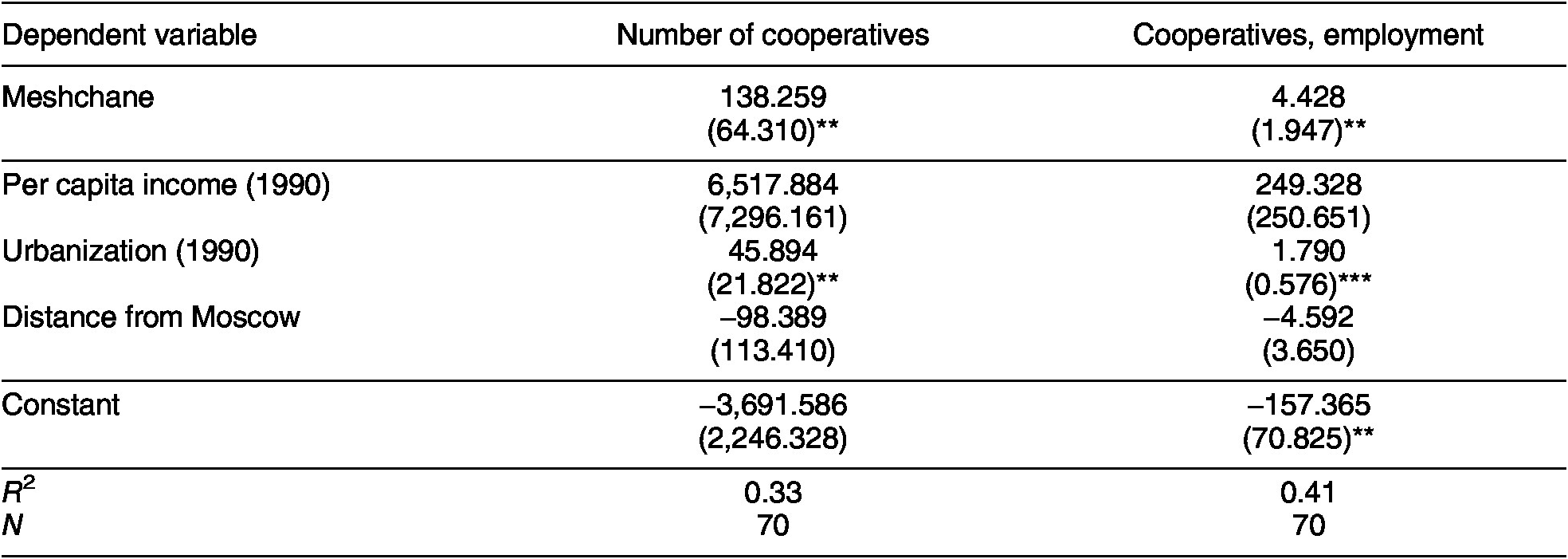

Were the meshchane’s entrepreneurial legacies in evidence during the Soviet period? This question is not entirely fanciful—the 1937 census, the last to employ Imperial social categories, revealed that many respondents were rentier. There was also a vast black market in consumer goods (Edele Reference Edele2011; Osokina Reference Osokina2001). One systematic proxy for communist entrepreneurship is the Gorbachev-era cooperative movement initiated in 1988. The “worker cooperatives” were largely indistinguishable in ownership structure from classic small and medium size enterprises in capitalist countries (Bim, Jones, and Weisskopf Reference Bim, Jones and Weisskopf1993). Table 5 demonstrates, using oblast-level statistics on cooperatives and their employees (published by Goskomstat) and controlling for Soviet developmental indicators, that meshchane significantly covary with perestroika-era proto-entrepreneurship. Put simply, if we take two regions with similar developmental characteristics as measured by urbanization and wealth, the region with significantly higher entrepreneurial activity in the late 1980s would also have had a higher population share of meshchane in 1897. An increase in meshchane share of 1 percentage point produced additional 138 regional cooperatives, with the average number being 1,840. We also run specifications controlling for literacy, to ascertain whether the effect is due to meshchane rather than an artifact of other estates with relatively high education levels (SA3.20).

Table 5. Meshchane and Cooperative Movement in the late 1980s

Note: The table reports correlations between the historical share of meshchane and number of cooperatives/size of cooperatives-employed workforce in the late 1980s. The unit of observation is region. Individual columns correspond to regressions with different dependent variables. Robust standard errors in parentheses. Regressions estimated using OLS.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 6. Meshchane and Entrepreneurship

Note: The table reports the correlations between the historical share of meshchane and characteristics of the small-to-medium-enterprise (SME) sector in 2012 per share of respondents in a region claiming to be willing to run their own business in the ARENA survey (https://sreda.org/arena). The unit of observation is region. Individual columns correspond to regressions with different dependent variables. Robust standard errors in parentheses. Regressions estimated using OLS.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Meshchane and Contemporary Entrepreneurship

Next, we employ available regional data on post-communist entrepreneurship as well as survey data on individuals’ willingness to start their own businesses (see SA3.20). We find significant covariance between the “old” bourgeoisie and present-day entrepreneurship, willingness to become entrepreneurs, and private-sector employment (from the representative public opinion survey). Thus, the share of those willing to start a business in a region rises by 2.5%, with a 10% point rise in meshchane share; the proportion of those interested in establishing their own businesses varies between 3% and 22%. SA3.20 reports the results of regressions of entrepreneurship variables on literacy in 1897. Because literacy has no significant effect on self-reported willingness to start a business, entrepreneurial legacies are in our analysis appropriately distinguished from those of human capital, though both, we argue, engender greater citizen autonomy in an autocracy. Controlling for literacy, the meshchane effect remains robust, except for private-sector employment.

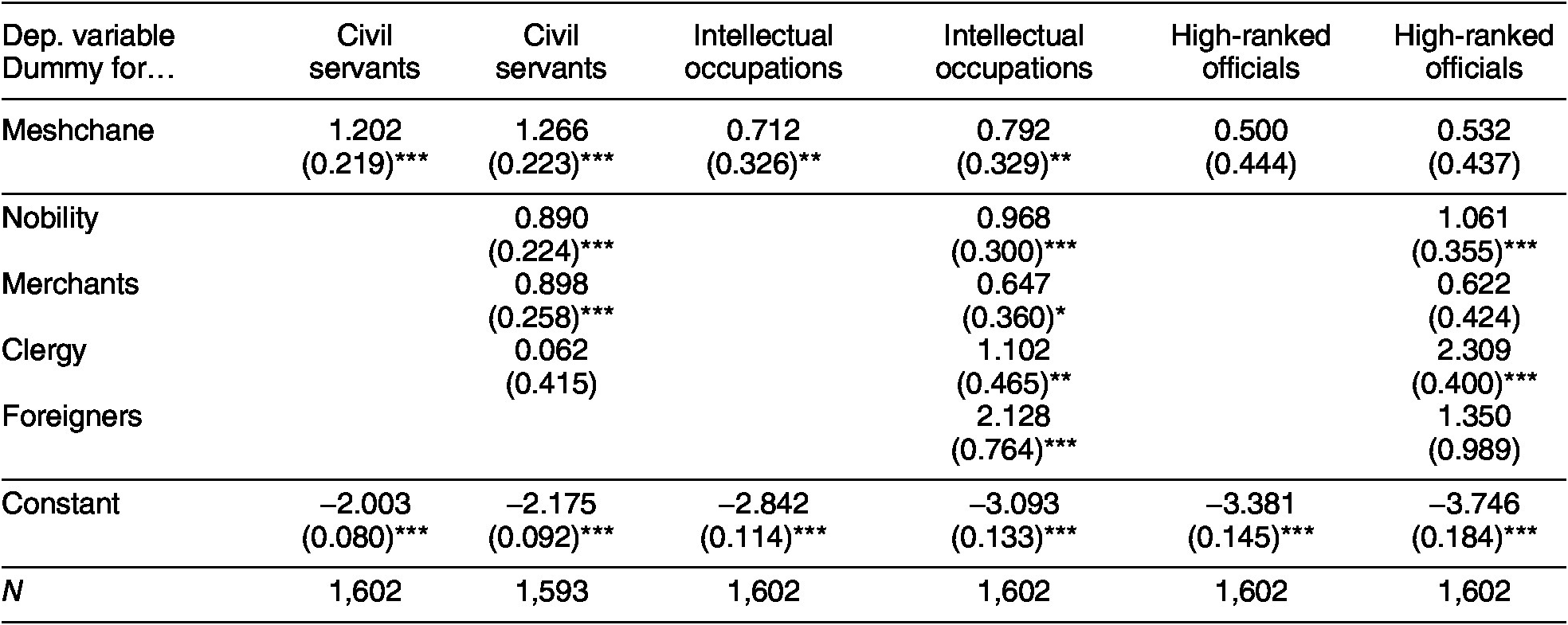

Legacies of Social Structure and Soviet Occupational Patterns: Survey Evidence

Up to now we explored the legacies of spatial variation in the distribution of estates. Because we are keen to address potential concerns of ecological inference, we commissioned a micro-level survey from Levada, Russia’s reputable polling agency.Footnote 7 In the first survey of this kind probing links between estate ancestry and occupational pathways, respondents were asked about the estate of their (great)-grandparents before the Revolution and their family’s Soviet-period social position. Details of the survey methodology are presented in SA4.

We begin by examining the self-reported Soviet-period social status of those claiming meshchane and other “educated” estates ancestry. This helps further probe whether meshchane’s descendants were likely to opt for skilled occupations (an alternative test of H2). Table 7 reports the covariance between self-reported Imperial origins and Soviet social status. We regress the estate data on human-capital-intensive Soviet occupations of parents encompassing civil servants (bureaucracy), intellectual occupations (teachers, doctors, engineers), and high-level state officials. We run two regressions in each case: one employing a dummy for those with meshchane origin and one with dummies for the other “educated” estates. The residual category is peasants, Cossacks, and smaller estates. We find that self-reported meshchane descendants are significantly more likely to report civil servant or intellectual occupations during the communist period. There is, however, no link between meshchane—and merchant—origin and high-level state positions. The result is consistent with our conjecture that the bourgeois estates became the backbone of professional middle class—a status distinct from position in the highest ranks of the state and party apparatus. And it suggests that the old bourgeoisie tended to opt for the least ideologically tarnished employment—the skilled professional, not party-managerial, routes to social mobility.Footnote 8

Table 7. Self-reported Meshchane Ancestry and Soviet-Period Occupation of Descendants

Note: The table reports the correlations between self-reported Imperial ancestry and occupation of parents in the Soviet period from the Levada survey. Individual columns correspond to regressions with different dependent variables and sets of explanatory variables. Regressions estimated using logit. Robust standard errors in parentheses. “Foreigners” dropped in one of the regressions due to perfect prediction.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Our micro-level data is an asset for our analysis also because it helps corroborate continuities in social structure in space. We merge our spatial and survey data to explore whether self-reported meshchane ancestry is correlated with historical share of meshchane in the respondent’s region. We find strong evidence that residents of regions with higher meshchane share in the past are also more likely to report meshchane ancestry. This finding is notable given the known compositional shifts in the population due to Soviet migration, repressions, and other dislocations (SA4.6). The developmental projects of the totalizing communist state may have profoundly affected Russian society, but they failed to completely obliterate the old regime’s social fabric. SA4.4 and SA4.5 show that self-reported ancestry has a strong and consistent with our theory effect on political outcomes, further supporting our argument.

DISCUSSION

We assembled original data and analyzed the implications of reproduction of the “old” middle class emerging within an “organic” context of capitalist development for democratic processes in a polity subjected to state-led modernization. Highly disaggregated pre-communist census data allow us to single out meshchane—a vestige of the estates-based feudal social order—as a proto-bourgeoisie. In late Imperial Russia, this group colonized the professions; engaged in trading, family enterprise, and rentier pursuits; and enjoyed legally enshrined self-governance earlier and greater in scope than the peasant subject populations. In what is an important finding for theories of the political role of the middle class in autocracies, we find strong covariance between the population share of these upwardly mobile groups and regional democratic competitiveness and media freedom, our proxies of democratic variations, over and above the effects of communist state-driven modernization.

Two hypothesized causal channels linking meshchane to regional democratic outcomes were proposed: (a) human capital stocks engendering a preference for higher education and prestigious professions and (b) intergenerational entrepreneurial value transmission. We acknowledge the parallel channel of the creation of educated strata from amongst hitherto underprivileged worker and peasant groups—the “new” middle class. But our statistical tests establish that the bourgeoisie nurtured within the more autonomous context of Imperial capitalist development is associated with significantly higher subnational democratic competitiveness and media freedom. To account for the apparent patterns of the reproduction of bourgeois values under communism, we consider policies intrinsic to the Soviet state’s developmental agenda, which built on pre-Revolutionary bourgeoisie’s human capital. We also explore the transmission of values related to both education and the market operating outside of Soviet policy.

We find strong and robust covariance between “bourgeois” legacies and regional distribution of professions like doctor and engineer, location of expertise-intensive “secret cities” furthering Soviet cutting-edge industrial programs, and even the spatial location of Gulag camps that likewise serviced the USSR’s developmental effort. There is also strong evidence of transmission of market-supporting values, which, unlike human capital, are more straightforwardly conceptualized as exogenous to Soviet policies. We find that meshchane are associated with not only perestroika-era proto-entrepreneurship but also with private business occupational choices outside of public-sector employment in present-day Russia. The analysis of author-commissioned survey data likewise reveals estate legacies consistent with the hypothesized mechanisms. These findings are confirmed in a battery of additional statistical tests and corroborated in author-assembled archival and memoir materials.

Our findings have significant implications for debates on the role of the educated middle classes in eroding, or, alternatively, augmenting authoritarianism. One promising strand of theorizing has highlighted that not all “educated” “white-collar” strata are made of the same cloth when it comes to orientations toward the political system (Chen Reference Chen2013; Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2017). Being “middle class” does not mean citizens would fail to cast a vote for autocracy. Far from it. Unfortunately, conventional survey and other data instruments force the scholar to work with generic categories of class, income, and occupation. These are insensitive to the fine historically conditioned and reproduced tapestries of variations among groups bracketed together. As our analysis demonstrates, these legacies may shape not only wider orientations toward the political sphere but also occupational choices that help sustain a modicum of independence from state pressures.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S000305542100023X.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Replication materials are available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JO8C7A.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Volha Charnysh, Keith Darden, Aditya Dasgupta, Scott Gehlbach, Theodore Gerber, Henry Hale, Steven Hoch, Otto Kienitz, Jeff Kopstein, Maria Kravtsova, Kyle Marquardt, Bryn Rosenfeld, Katerina Tertytchnaya, Daniel Treisman, and Yuri Zhukov for insightful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript and sharing data. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the APSA 2017 and 2018 annual conferences; the ASEEES 2018 conference; the PONARS Conference on Conflict, Contestation and Peacebuilding in Eurasia in 2018; the Venice Seminar in Analytical Sociology in 2018; the German Association for East European Studies Economic Section Conference in 2018; the DC Area Post-communist Politics Social Science Workshop at George Washington University in 2019; the Summer Workshop in the Economic History and Historical Political Economy of Russia at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2019; and the European Politics Working Group seminar at the University of Berkeley in 2021. We also appreciate the excellent research support of Giovanni Angioni, Lana Bilalova, Julia Blaut, Daniel Fitter, and Marnie Howlett. All errors are of course solely those of the authors.

FUNDING STATEMENT

Tomila Lankina is grateful for generous funding from LSE’s Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines (STICERD); the LSE Centre for International Studies; the LSE Department of International Relations; the Paulsen fund at LSE; and the LSE International Inequalities Institute. Alexander Libman is grateful for the support of the International Center for the Studies of Institutions and Development of the National Research University Higher School of Economics, which provided some of the data for the study. He also acknowledges the funding received within the framework of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE) and the Russian Academic Excellence Project “5-100.”

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.