Introduction

This article explores the role of institutions in shaping the politics of policy change. Since we habitually start from the agenda-setting stage to analyse the process of policy change, we use the powerful lens of the Multiple Streams Approach (MSA)Footnote 1 , which provides analytical advantages in dissecting the politics of this process. In a nutshell, MSA helps us trace the origins of a policy change through its five structural elements by focusing on how a policy entrepreneur, facing a perceived problem, sets the agenda by seizing a window of opportunity to push a policy solution when the political climate happens to be right (Kingdon Reference Kingdon2003, p. 189). Politics of policy change does not take place in an institutional vacuum. All of these structural elements are, therefore, institutionally embedded. In chasing after the politics of policy change in different geographies, we, thus, ask: Which institutions should we focus on when we study the politics of agenda-setting in different geographies? How do these institutions shape MSA’s structural elements?

Scholars who work on the politics of policy change have increasingly been relying on MSA over the last three decades. MSA was originally developed to depict the politics of policy change by focusing on the agenda-setting stage in the USA (USA). This approach assumed the institutional setting of American politics as given. As the geography of MSA expanded, scholars brought in formal political institutions as explanatory variables to account for varying outcomes (Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis1992, Reference Zahariadis2003, Reference Zahariadis2016; Béland and Howlett Reference Béland and Howlett2016; Sætren Reference Sætren2016b; Zohlnhöfer Reference Zohlnhöfer2016; Zohlnhöfer et al. Reference Zohlnhöfer, Herweg and Huß2016; Koebele Reference Koebele2021). They do so by arguing that institutions are “intervening variables (or structuring variables) through which battles over interest, ideas and power are fought” rather than variables having direct independent effects (Steinmo Reference Steinmo, Clarke and Foweraker2001, p. 571). Some emphasised how the parliamentary system in Germany forced political entrepreneurs to pursue different strategies than those featured in MSA studies on the USA (Zohlnhöfer Reference Zohlnhöfer2016; Zohlnhöfer et al. Reference Zohlnhöfer, Herweg and Huß2016). Others showed how the Norwegian executive-legislature relations determined the location and strategies of policy entrepreneurs (Sætren Reference Sætren2016b). Still, others demonstrated how spillover effects across different units in compound polities in the USA and the European Union (EU) open policy windows enabling policy changes (Mintrom Reference Mintrom1997; Ackrill and Kay Reference Ackrill and Kay2011). All these avenues of research nicely illustrate how different formal political institutions in different geographies shaped the politics of policy change in different ways.

In addition to formal political institutions, a handful of MSA applications introduced a set of informal rules into their analyses. Some scholars showed how past policies, as informal rules, structure the ways in which conditions are framed as problems in the USA (Weir Reference Weir, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992). Others emphasised how systems of interest intermediation and representation created path dependence and structurally empowered some policy communities over others in generating policy proposals in Latin America and Sweden (Spohr, Reference Spohr2016b; Sanjurjo, Reference Sanjurjo2020). Still, others examined how predominant approaches to policymaking, once institutionalised, shape where windows open leading to policy change in China and India (Liu and Jayakar Reference Liu and Jayakar2012). These MSA applications featuring informal rules provided us with clues as to how institutions effectively structure the politics of policy change as well (Steinmo et al. Reference Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992).

As MSA explored new lands, we learned how spatially- and temporally bound institutions structure the politics of agenda-setting processes in different ways. Focusing on the effects of these rules of the game promises us to compare the politics of agenda change in different contexts systematically. We, therefore, argue that only through focusing on institutions, which tell us “who can play and how they play” in agenda setting, can we explain the comparative politics of policy change (Steinmo Reference Steinmo2015, p. 181). After all, institutions provide “incentives and constraints for political actors” and thus “structure the political struggle itself” as it happens in real-timeFootnote 2 (Steinmo Reference Steinmo, Clarke and Foweraker2001, p. 571). We also argue that we need a “fine-grained” approach to institutions not only in revealing differences in the politics across sectors, time, and geographies (John Reference John2012, p. 56) but also in bringing formal and informal rules together. In this article, we illustrate how we can weave institutions more tightly into MSA’s backbone with the help of existing case studies.

In this article, we explore how MSA’s each structural element is institutionally structured. In problem definition, we illustrate how institutions distribute power, and hence, shape whether, to what extent, and how actors perceive and construct problems. Policy solutions are filtered by institutions that distribute resources among policy communities, bias their preferences, and determine where they operate. Institutions structure the political environment by distributing power and requiring consensus building among organised political forces and shaping public opinion, and the timing in which authorities address it. Institutions determine the location and the longevity of windows of opportunity. Institutions inevitably filter who gets to play the role of policy entrepreneurs, their strategies, and chances for success.

In terms of our research approach, we bring institutionalist insights into the politics of agenda setting. We adopt a broader conceptualisation of institutions as “building-blocks of social order” (Streeck and Thelen Reference Streeck and Thelen2005, p. 9), emphasis in original). Here, institutions “represent socially sanctioned, that is, collectively enforced expectations with respect to the behavior of specific categories of actors or to the performance of certain activities” (Streeck and Thelen Reference Streeck and Thelen2005, p. 9). They include “formal rules, compliance procedures and standard operating practices that structure the relationship between individuals and various units of the polity and the economy” (Hall Reference Hall1986, p. 19). In this conceptualisation, institutions are “regularized practices with a rule-like quality in the sense that the actors expect the practices to be observed; and which, in some but not all, cases are supported by formal sanctions” (Hall and Thelen Reference Hall and Thelen2008, p. 9). Thus, while some institutions are “formal (as in constitutional rules),” some others are “informal (as in cultural norms), but, without institutions, there could be no organized politics” (Steinmo Reference Steinmo2015, p. 181).

Adopting a broader conceptualisation of institutions, we highlight the ways in which the politics of agenda and policy change in different countries are structured by different sets of nationally-, sectorally-, and temporally specific not only formal but also informal rules. In many cases, informal rules, as much as formal rules, shape whether a problem is recognised, whether an alternative reaches the agenda and becomes a decision, how politics facilitates policy change, where policy windows open, and who gets to be an entrepreneur. Thus, we feel the need to bring informal rules to the forefront, which have traditionally remained in the background in much of public policy research. The comparative literature is replete with cases where the politics of policy change in two systems with similar formal political institutions differ due, more often than not, to different informal rules. In this broader definition of institutions, informal rules as much as formal ones “involve mutually related rights and obligations for actors, distinguishing between appropriate and inappropriate, ‘right’ and ‘wrong,’ ‘possible,’ and ‘impossible’ actions and thereby organizing behavior into predictable and reliable patterns” (Streeck and Thelen Reference Streeck and Thelen2005, p. 9). This conceptualisation allows us to explore how a panoply of formal and informal rules structure the politics of policy change in multiple streams in different institutional settings worldwide.

In terms of our methodology, in order to reveal how varying institutions structure the politics of policy change in different geographies, we bring together diverse case studies drawing on MSA and New Institutionalism. These cases help us identify which formal and informal rules shape problem stream, policy stream, political stream, problem windows, and policy entrepreneurs. The cases we selected to trace institutional effects span diverse sectors in varying geographies.Footnote 3 They are sufficiently abstract whose findings travel easily across other institutional contexts represented by unitary, federal, confederal polities; parliamentary, presidential, and semi-presidential systems; pluralist, corporatist, and statist interest intermediation systems; liberal, conservative, and social democratic welfare states; and proportional representation and majoritarian electoral systems. The institutions in the cases we focus on are located in Europe (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Finland, France, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the European Union), Latin America (Brazil), Asia (China, India, and Thailand), and the Middle East (Israel and Turkey). We also rely on the USA (where MSA originates from) as our comparator.

We learned from New Institutionalism that politics is structured in space and time. In order to reveal patterns of institutional effects on the politics of policy change, we draw on inter-spatial, inter-sectoral, and inter-temporal comparisons in this article. We hope to shed light on the effects of institutions in uncharted locations based on what we already know on the institutional effects in existing case studies with similar scope conditions. By doing so, we also hope to respond to the call of the co-editor of this journal, Peter John, who cautioned us to pay “attention to the rules about who makes decisions, what powers they have, what is the official sequence of the policymaking process, and what constraints decisionmakers operate under” to understand how policies are made (John Reference John2012, p. 29). Others working on MSA echo the need to bring institutions into the framework (Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2016; Zohlnhöfer et al. Reference Zohlnhöfer, Herweg and Huß2016).

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the architecture and the structural elements of MSA as well as institutions in John W. Kingdon’s work and beyond. Section 3 explores how institutions as formal and informal rules shape each of MSA’s structural elements. Section 4 concludes by summarising our key findings.

MSA: Architecture and institutions

Architecture and the structural elements of MSA

The architecture of MSA relies on five structural elements, each of which is conceptualised independently of one another. The problem stream involves the interpretation process of conditions interpreted as problems through indicators, focusing events, and feedback. These subelements help process and interpret how existing conditions fail to meet the public’s expectations, thereby creating problems. The policy stream is composed of policy communities that produce policy proposals to address problems. In the policy primeval soup, policy alternatives compete against each other to survive. A proposal’s survival depends on its technical feasibility, value acceptability, cost and benefit distribution, public acquiescence, and politicians’ receptivity. The political stream refers to the national mood, organised political forces, and changes in the government and the legislature. In this stream, key political actors determine which issue should enter the agenda and to what extent it would require consensus building among different groups. Policy windows may open in two streams: the problem stream or the political stream. Problem windows result from unpredictable problems, whereas political windows provide policy entrepreneurs with a sort of predictability such as regular elections. In both types of windows, policy entrepreneurs couple three streams to set the agenda. These actors may be inside or outside the government, and they may assume elected or appointed posts.

Institutions in Kingdon’s work and beyond

In his original work, Kingdon did not explicitly discuss the roles institutions play in the structural elements of his framework. He still provided us with significant clues as to the institutional mechanisms and the institutional features of the American policy process. For example, he illustrated how obvious institutional characteristics of the USA, i.e. federalism, pluralism, and its presidential system shape the structural elements of MSA. Furthermore, he typically referred to other types of institutions playing roles in these structural elements: values in the problem stream; technical feasibility, value acceptability, tolerable costs, and level of anticipated public acquiescence in the policy stream; consensus building in the political stream; spillovers in the policy window; and rules of the game in the operations of the policy entrepreneur.

In most MSA applications mentioning institutions, scholars generally focus on formal rules. These are defined as “arenas” (Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2016, p. 8) and the “constitutive key elements of the politico-administrative system like the cabinet, ministries, central agencies, and the legislature” (Sætren Reference Sætren2016b, p. 73). Institutions, in these studies, for example, shape “the institutional context of policy windows” (Zohlnhöfer et al. Reference Zohlnhöfer, Herweg and Huß2016, p. 245) and the location of policy entrepreneurs (Mintrom and Norman Reference Mintrom and Norman2009; Roberts and King Reference Roberts and King1991; Steinmo Reference Steinmo2015, p. 181; Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2003).

In other MSA applications, scholars also allude to informal rules, albeit without particularly distinguishing these from the formal ones. This time, they see institutions as “informally embedded social rules that may constrain or enable policymaking” (Béland Reference Béland2016, p. 236; Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2016, p. 1). These rules stem from “historically derived political and administrative cultures and resulting in unique national policy styles and politico-administrative traditions” (Sætren Reference Sætren, Zohlnhöfer and Rüb2016a, pp. 28–29; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2002, p. 629). Some follow the classic Northian definitions of institutions that go beyond formal rules and define “the rules of the game in politics” (Mintrom and Norman Reference Mintrom and Norman2009, p. 656; Sætren Reference Sætren, Zohlnhöfer and Rüb2016a, p. 28). Others emphasise the informal nature of institutions by defining them as “informal rules (social norms), that shape constellations of actors and their goals” (Spohr Reference Spohr, Zohlnhöfer and Rüb2016a, p. 251; Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2016). For example, informal rules in these studies structure the policy communities in the policy stream (Rozbicka and Spohr Reference Rozbicka and Spohr2016; Spohr Reference Spohr, Zohlnhöfer and Rüb2016a, p. 269), the origin of policy windows, and how long these windows need to remain open for bringing agenda change (Ackrill and Kay Reference Ackrill and Kay2011; Becker Reference Becker2019; Liu and Jayakar Reference Liu and Jayakar2012).

Structuring multiple streams: The role of institutions

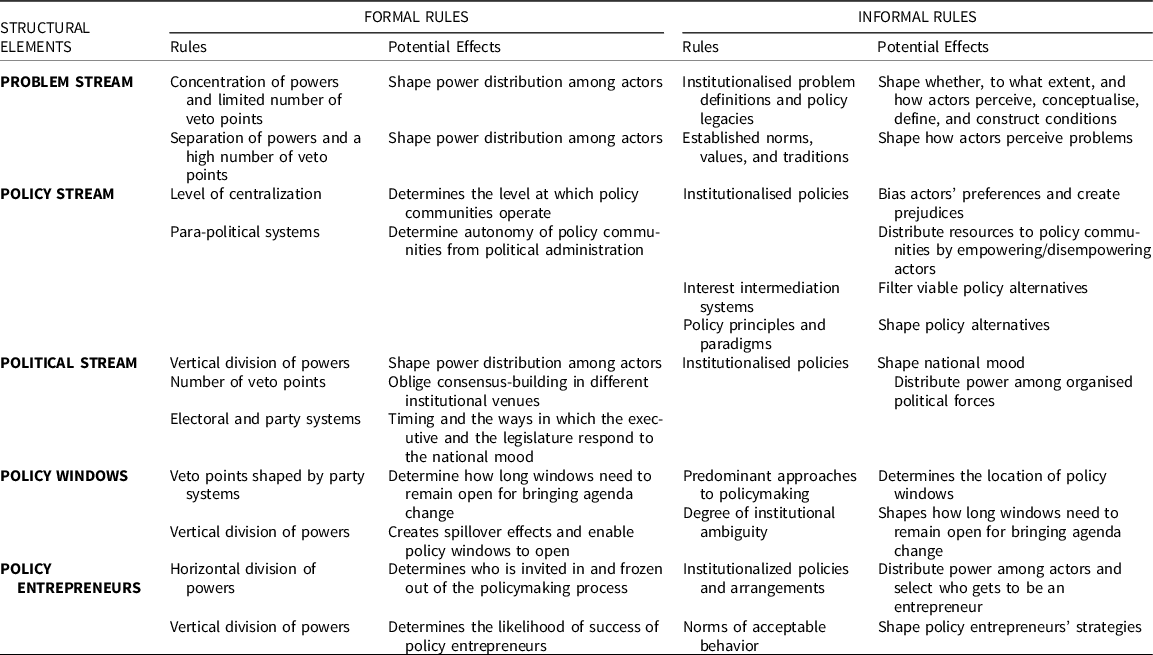

We depart from where MSA studies leave us and explore how institutions structure the politics of policy change in multiple streams. We propose to distinguish formal rules from informal ones as we observe that different policy outcomes do not only and necessarily result from different formal rules. We find that different informal rules do affect how the balance of power among who can play and how they play in two settings sharing similar formal rules.Footnote 4 Examples of formal rules we highlight in this article include constitutional arrangements on horizontal and vertical divisions of power, degree of separation of powers, electoral systems, number of veto points, level of centralisation, and para-political institutions. Examples of informal rules we draw attention to include path-dependent norms, values, traditions, long-established policies, interest intermediation systems, policy principles and paradigms, politico-administrative cultures, degree of institutional ambiguity, and prevailing rules of the game. These formal and informal rules, which we present in Table 1, are neither jointly exhaustive nor mutually exclusive. We hope scholars will further explore how other rules of the game shape who can play and how they play in multiple streams.

Table 1. Examples of how institutions shape MSA’s structural elements

How do institutions structure the problem stream?

Formal and informal rules in different geographies shape the problem stream in different ways. Which actors have positional advantages in different institutional contexts for defining problems? How do past policies in a given institutional setting, as informal rules, configure the choice set of problem definers? In addressing these questions, we hope to shed some light on the ways in which formal and informal rules structure the problem stream.

For most MSA scholars, the problem stream is conceptualised largely independent of formal political institutions (Zohlnhöfer Reference Zohlnhöfer2016, p. 88). Formal rules do not explicitly feature in how scholars explain, for example, which actors are more likely to emerge as problem brokers. Instead, scholars focus on other conditions intrinsic to the nature of problems, such as whether a condition is central to re-election or not (Herweg et al. Reference Herweg, Huß and Zohlnhöfer2015; Zohlnhöfer Reference Zohlnhöfer2016). Although MSA literature did not explicitly construct links between institutions and the problem stream, there are theoretical reasons to look for variation in the impact of formal and informal rules on problem definition. The institutionalist literature provides us with many case-based examples that would help us better understand the politics of the problem stream. In terms of formal rules, for example, a case under investigation may be represented by a political system with the concentration of powers and a limited number of veto points. In this case, actors in the executive would have positional advantages in framing conditions as problems and would, thus, emerge as problem brokers (Knaggård Reference Knaggård2015). In contrast, in a case represented by a political system with separation of powers and a high number of veto points, small groups would be able to enter into competition with the executive in framing problems (Immergut Reference Immergut1992). Another example may be a political system with a high degree of centralisation and insulation of the bureaucracy from electoral pressures (Immergut Reference Immergut1992). In this case, we would not be surprised if bureaucrats, as empowered actors, have positional advantages in framing conditions as problems. In any case, formal political institutions, due to their configuring characteristics as well as their enabling and constraining effects, will select the most likely problem broker in a chosen setting.

In terms of informal rules, Kingdon’s (Reference Kingdon2003, p. 90, 224) emphasis on path-dependent problem definitions as well as values provide a fertile ground to bring institutions back into the problem stream. By creating path dependence, established norms, institutionalised problem definitions, as well as policy legacies shape the problem stream in at least two ways. First, institutionalised problem definitions and policy legacies frame whether, to what extent, and how actors perceive, conceptualise, define, and construct conditions as problems. In this way, institutionalised policies, as informal rules themselves, shape and constrain present as well as future problem definitions (Pierson Reference Pierson, Shapiro, Skowronek and Galvin2006, pp. 114–131). A given problem definition, therefore, is typically patterned after “pre-existing preferences for particular policies” (Birkland and Warnement Reference Birkland, Warnement, Zohlnhöfer and Rüb2016, p. 92). In fact, institutionalists contributing to MSA have been emphasising how past policies structure the ways in which problems are “conceptualised and defined” (Weir Reference Weir, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992). Focusing on inherited problem definitions as informal rules, therefore, promises to help us understand the rationale behind the preferred problem choice sets. Second, established norms, valuesFootnote 5 , and traditions structure actors’ perceptions of problems (Sager and Thomann Reference Sager and Thomann2017, p. 289). For example, while pressures stemming from globalisation may be welcomed by problem definers in the liberal Anglo-Saxon welfare state regime, the same pressures may be seen as threats by problem definers in the social democratic Scandinavian welfare state regime (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1996). Another example is the evolution of education policies in England and Norway, facing similar exogenous pressures. Although England and Norway share many formal rules, defining problems in education policies diverged, given their different welfare regime characteristics structuring problem definition processes (Helgøy and Homme Reference Helgøy and Homme2006). A problem definition is, therefore, likely to change from one setting to another due to problem definers’ varying value systems and conception of the “ideal state” (Kingdon Reference Kingdon2003, p. 110; Spohr Reference Spohr, Zohlnhöfer and Rüb2016a). In both countries above, welfare regimes, as informal rules, are embodiments of past problem definitions. Problem definers in countries with similar formal rules perceive problems in different ways in different welfare regimes. Therefore, influential actors’ values on “institutional arrangements, rules, and understandings” filter problem definitions in different institutional settings in different ways (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990, p. 80).

How do institutions structure the policy stream?

How do institutions determine the level at which policy communities operate in different geographies? Which formal rules determine their autonomy from political administration? How do these shape (who forms) policy communities? How do institutionalised policies, interest intermediation systems, policy principles, and paradigms shape the prospects for policy alternatives in reaching the decision agenda? Having knowledge of formal and informal rules in different geographies helps us answer these questions. We explore how institutions structure the sub-elements of the policy stream – policy communities, actors playing different roles in these communities, and criteria for their survival.

Formal rules shape the policy stream in several ways. First, the level of centralisation of a political system configures the level at which policy communities operate. In the area of railroad policy, for example, in federal systems such as the USA, dispersion of power to states and local governments led policy communities to generate policy alternatives primarily at the regional level. In centralised unitary states such as France, however, the centralisation of power in the capital led policy communities to produce policy alternatives in the same policy area, yet this time, exclusively at the national level (Dobbin Reference Dobbin2004). The level of centralisation, therefore, directly shapes the policy venue where policy community members join one another and generate alternatives.

Second, formal political institutions shape the degree of autonomy of the “para-political sphere,” hosting policy community members from political administration (Beland Reference Beland2005, p. 8; Koebele Reference Koebele2021). The extent to which members of the policy communities are autonomous from political administration varies from one national setting to another. Thus, exploring how formal institutions affect the domestic para-political spheres helps us reveal, for example, the behaviour of policy communities functioning in these spheres. A key institution in the para-political sphere that shapes the behaviour of policy communities is the policy advisory system (Blum and Brans Reference Blum, Brans, Brans, Geva-May and Howlett2017). In France, the para-political sphere is formally organised in much less autonomous ways than it is in other institutional settings, such as the USA. In the French statist policy advisory system, the French government provides institutionalised access to policy community actors through government-sponsored agencies. For example, the Centre National de Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), sponsored by the government, hosts these actors. In contrast, in the USA, the organisation of the para-political sphere is largely independent of the administration and political parties (Beland Reference Beland2005). Moreover, the level of autonomy of the para-political sphere provides us with clues as to where members of the policy community would be found. If we are to look for acceptable academic members of a policy community in France, we are more likely to find them among civil servants in and around the CNRS. In the USA, however, the para-political sphere will be much more pluralist, and therefore, we are not likely to find academic members of a policy community in and around a specific single venue. Exploring the institutions that shape the level of independence of the para-political sphere from key government institutions will help us understand who are likely to become members of the policy community.

Informal rules, too, shape the policy stream. Among these are institutionalised policies, interest intermediation systems, policy principles, and paradigms.Footnote 6 First, institutionalised policies structure the policy stream in two ways. In biasing preferences of actors and creating prejudices, institutionalised policies structure how policy proposals evolve and are selected. This, in turn, determines the choice set of policy solutions that are available to key policy actors (Spohr Reference Spohr, Zohlnhöfer and Rüb2016a, p. 264; Weir Reference Weir, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992, p. 191; Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2016, p. 6). Another way institutionalised policies structure the policy stream is through providing funding and other resources to previously favoured policy solutions (Sheingate Reference Sheingate2003, p. 192; Weir Reference Weir, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992, pp. 191–192). Public policies distribute resources to different types of groups in society. They, thus, offer resources to policy communities that key policymakers view as producers and re-producers of favoured policy solutions. Policies, in this way, financially empower these communities in their efforts to dominate agenda-setting processes (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2014, p. 646).

Second, systems of interest intermediation and representation shape the policy stream by filtering which policy alternatives would reach the decision agenda. The decision agenda will be open to policy alternatives that would not challenge the ways actors have come to operate in these systems. In Latin America, in the area of anti-corruption policy, for example, long-standing unwritten rules reflected in corporatist practices empowered business associations in the political battlefield barring anti-corruption proposals stemming from other actors to reach the agenda (Sanjurjo Reference Sanjurjo2020, p. 210). In Europe, the interest intermediation system in Sweden, which did not require a consensus among social partners, unlike in Germany, allowed a similar policy proposal to reach the decision agenda more easily (Spohr Reference Spohr2016b, p. 264).Footnote 7 These examples illustrate that the exact policy solutions have different fates in different institutional settings with different interest intermediation systems. Therefore, taking into account interest intermediation systems, as informal rules, will help us predict the fate of a policy solution in reaching the agenda in different institutional settings.

Third, predominant policy principles and paradigms structure the policy stream by filtering the set of available policy solutions. Policy communities, members of whom share the same policy paradigm, are likely to converge on similar policy proposals. They will do so even if and when the contextual conditions change (Berman Reference Berman2006, p. 32). Even from the beginning, for a policy alternative to be viable, it needs to be developed within the boundaries of existing policy principles and paradigms. These informal rules, therefore, effectively shape the content of policy alternatives in the policy stream.

How do institutions shape the political stream?

When we apply MSA to cases beyond the USA, we need to sensitise ourselves to how the nationally specific formal and informal rules affect the political stream in the country we are studying. We, thus, need to focus on how institutions structure the subelements of the political stream: interest group behaviour, the national mood, turnover of key personnel as governments come and go, and why and when consensus is built in the political stream. In exploring agenda and policy change, a focus on institutions helps us contextualise these subelements of the political stream in a given political setting. Accordingly, we ask: Why do some interest groups have more power in setting the agenda in some geographies than in others? How do institutions impose consensus building in the political stream? How do they determine the level at which consensus needs to be built? Which institutional rules shape the national mood and how? How do informal rules afford positional advantages to organised political forces?

Formal political institutions shape the subelements of the political stream in many ways. First, formal rules constituting political systems shape the distribution of power among organised interests. This, in turn, empowers some societal actors in agenda-setting processes in some settings than in others. One example is how the vertical division of powers in a given country shapes the extent to which physicians have an impact on the political stream in the area of national health insurance policy (Immergut Reference Immergut1992, p. 29). In Switzerland, key decisionmakers take into account the voice of physicians in national health insurance policy since they have the veto to block any legislation in this area. In contrast, in France, physicians are institutionally less privileged than their Swiss colleagues in shaping the same policy sector (Beland Reference Beland2005, p. 3). Scholars need to focus on different institutional contexts that shape the terms in which national decisionmakers in these settings find themselves interacting with powerful organised political forces.

Second, formal political institutions determine the number of formal veto points that limit the possibility of change to agendas and policies (Spohr Reference Spohr, Zohlnhöfer and Rüb2016a, p. 253). Veto points in different political systems may force actors to build consensus at different institutional venues. Institutionalised “patterns of democracy” (Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012) help us think about these venues. In a coalition government in a consensual democracy, such as Belgium, actors will seek to build consensus among coalition partners in government given the Belgium institutional arrangements. In contrast, in a single-party government in a majoritarian democracy, actors will not feel the need to build consensus with other political parties that make up the legislature. Scholars who emphasised the importance of formal political institutions such as electoral systems in consensus building reach similar conclusions (Zohlnhöfer et al. Reference Zohlnhöfer, Herweg and Huß2016). The institutionalist emphasis on consensus building in the political stream directs us to where and whom to look at in analysing both agenda -setting and policy adoption processes.

Third, formal institutions, such as electoral systems, structure the political stream by shaping the composition of the executive and the legislature. These institutions also shape the timing and the ways in which the executive and the legislature respond to changes in the national mood (Zohlnhöfer et al. Reference Zohlnhöfer, Herweg and Huß2016, p. 246). Relatedly, the comparative political science literature shows that different party systems systematically produce different kinds of governments (single-party governments versus multi-party coalitions). Single-party governments are more likely to respond to shifts in national mood more swiftly than multi-party coalitions without particularly seeking the approval of other parties (Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2004). Scholars applying MSA to different political settings would benefit from exploring how electoral systems and party systems determine the time within which ruling governments respond to changes in the national mood.

Like formal rules, informal rules, too, structure the political stream. They do so in at least two ways. First, once established, widely popular policies become institutionalised through time. In doing so, as an informal rule, they shape elements of the political stream, such as the national mood. For example, social protection programmes, such as the Affordable Care Act (otherwise known as Obamacare), are likely to remain beyond the reach of future administrations’ retrenchment attempts given the consistent (and resilient) support for most of the central elements of the law. During the early years of the Trump administration, Republicans’ attempts at repealing and replacing the bill did not find much support from the public. The national mood, which was patterned by the popularity of the programme, was generally averse to any attempt at retrenchment. This meant that such a move was foreclosed from the beginning as Obamacare was widely seen as the most popular legislative attempt over the recent decades. Even though a solution was readily available, the popularity of Obamacare, as an informal rule, did not allow the administration to move forward with this reform attempt (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2018, p. 554). This shows that decisionmakers seeking popular support for their agenda items operate in an environment heavily shaped by institutionalised past policies.

Second, established policies, which become institutionalised through time, shape the political stream by distributing power among organised political forces, another subelement of this stream. Past policies empower some groups over others. Kingdon himself gives the example of the highway lobby, which protected existing policies at the expense of new policies (Kingdon Reference Kingdon2003: 150–152). New Institutionalist work is replete with examples of how entrenched interests organised around institutionalised policies shape the political stream. For example, the traditionally empowered teachers’ unions in the USA, as vested interest groups, are pivotal in influencing key political actors when they are shaping education reforms (Moe Reference Moe2015, pp. 304–307). Another example is the Ghent system, which as a long-standing policy, institutionalised the relationship between state and labour unions. The system, which emerged in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden during the 1930s, assigns significant power to labour unions in the area of unemployment insurance programmes. The political stream is structured such that whoever comes to power with a reform agenda will have to listen to labour unions even if this means disfavouring business groups (Scruggs Reference Scruggs2002). In the political stream, informal institutions, such as long-standing policies, in one political setting shape the relative power of organised political forces in different ways than in another political setting.

How do institutions shape policy windows?

Findings show that nationally specific formal and informal rules shape the origin and longevity of policy windows in diverse geographies in different ways. Originating from these, we ask: How do institutions determine how long windows need to remain open for bringing agenda change? In which institutional settings are policy windows more amenable to spillover effects? How do institutions determine where policy windows typically open? How do informal rules such as institutional ambiguity shape how long windows need to remain open for bringing agenda change?

First, the number of veto points, as formal rules, is likely to shape how long windows need to remain open for bringing policy change, hence their longevity (Blankenau Reference Blankenau2001). The time actors need for a policy change to be successful varies from one political system to another due to diverse numbers of veto points. This is particularly the case for “decision windows,” much more so than for agenda setting (Herweg et al. Reference Herweg, Huß and Zohlnhöfer2015, pp. 444–446). Parliamentary systems, compared to presidential systems, for instance, generally have a lower number of institutionalised veto points (Immergut Reference Immergut1992). In particular, a single-party government having a majority in the legislature is likely to face fewer veto points during decisionmaking in parliamentary systems than in presidential ones. A policy window remaining open for a short period of time, therefore, is likely to suffice for a policy change due to fewer veto points supported by its closely-knit legislative-executive relationsFootnote 8 (Blankenau Reference Blankenau2001, p. 40). In contrast, in presidential systems, a window may need to remain open for a longer period of time due to multiple veto points (Blankenau Reference Blankenau2001, p. 40). Therefore, the number of veto points in a political system is likely to structure the optimal longevity needed for a policy change. When applying MSA to different settings, scholars should consider the number of veto points that may structure the longevity of decision windows.

Second, formal political institutions, such as vertical division of powers, shape the extent to which spillover effects help open policy windows. For example, in a federal political setting, a successful policy solution in one subnational unit may create a learning effect for another. Such spillover effect, in this way, leads to the opening of a policy window in the other subnational unit (Mintrom Reference Mintrom1997; Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2003, p. 18). In unitary systems, however, such spillover effect is unlikely to emerge unless the unitary state in question learns from another. Thus, when scholars apply MSA to federal polities, they would benefit from looking for spillover effects among subnational units on policy windows. For unitary systems, focusing on inter-state spillovers would be helpful to observe their effects on policy windows.

Informal rules, too, shape policy windows. They do so in at least two ways. First, informal rules, such as predominant approaches to policymaking, shape where policy windows open. Being accustomed to informal rules such as these in an institutional setting will help policy entrepreneurs sense whether policy windows open in the problem stream or in the political stream. If windows are likely to open in the problem stream, entrepreneurs will tailor their solutions to the problems. If windows are prone to open in the political stream, entrepreneurs should keep their solutions ready to chase a problem (Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2008). Applications on China (where nonincremental approaches prevail) and India (where incremental approaches are the norm) nicely illustrate this. The literature shows us that in institutional contexts where policymaking follows a non-incremental approach, windows open in the political stream. Consequently, policy entrepreneurs in these settings (e.g. in China) present their pet solutions with the opening of a political window to change the agenda. In institutional contexts where policymaking follows an incremental approach, however, policy windows open in the problem stream. Accordingly, policy entrepreneurs (e.g. in India) tailor their pet projects to the problems as windows open in the problem stream (Liu and Jayakar Reference Liu and Jayakar2012).

Second, informal rules, too, such as the degree of institutional ambiguity (high versus low ambiguity), shape the longevity of policy windows (Ackrill and Kay Reference Ackrill and Kay2011; Becker Reference Becker2019). This might be best exemplified across different policy sectors characterised by different institutional features in a given single formal institutional setting. In the European Union, different levels of ambiguity, as unwritten rules, in different policy sectors present varying opportunities as to policy window openings. Depending on the degree of institutional ambiguity in a given sector, a change in one policy sector (whose contours may or may not be intertwined with others) may allow the opening of a policy window in a related policy sector (Ackrill and Kay Reference Ackrill and Kay2011, p. 75). Scholars call window opening resulting from institutional ambiguity in a given sector “endogenous spillovers.” As policymakers set the agenda on sugar policy in the EU, this creates endogenous spillovers into other policy sectors such as trade and development, which are represented by high institutional ambiguity (Ackrill and Kay Reference Ackrill and Kay2011). The opening of the first window in the agriculture sector opens a second and a third window in trade and development and extends their longevity more than what would have been the case otherwise. Therefore, a change in one policy sector may make changes possible in related policy sectors with high institutional ambiguity. Here, endogenous spillovers render new windows to be exploited by policy entrepreneurs for a longer period. In contrast, lower institutional ambiguity in the area of the Economic and Monetary Union limits the uncertainty for potential entrepreneurs to benefit from endogenous spillovers stemming from deepening reforms in the EU’s Social Dimension (Dupuy and Jacquot Reference Dupuy, Jacquot, Zahariadis and Buonanno2018). Therefore, the higher the ambiguity is in an institutional context, the longer the subsequent policy windows remain open. Consequently, policy entrepreneurs in contexts with higher institutional ambiguity are better placed than others in terms of window openings. In applying MSA, therefore, we need to take into account the level of institutional ambiguity, as informal rules governing behaviour, which will help us predict the longevity of policy windows.

How do institutions shape policy entrepreneurs?

Formal and informal rules in different geographies shape the location of policy entrepreneurs, the likelihood of their success, who gets to be a policy entrepreneur as well as their strategies. Thus, we ask, how do countries differ in terms of the institutional venues entrepreneurs operate? How do these venues affect the jurisdictions policy entrepreneurs choose to pursue policy agendas? How do established policies provide policy entrepreneurs with authority? How do informal rules, such as norms or acceptable behaviour and historical legacy, shape the strategies policy entrepreneurs follow?

First, formal political institutions, such as horizontal division of powers, may determine the main venues where policy entrepreneurs need to operate. In some settings, policy entrepreneurs may not need to operate within the innermost circle of the policymaking process. In parliamentary systems such as Norway, however, being an insider looks like a condition for entrepreneurship. Here, the closer the actors are to key executive actors (such as cabinet members), the more likely they will be able to emerge as entrepreneurs. This is especially true if the issue at hand is deemed sensitive by influential actors (Sætren Reference Sætren2016b). MSA scholars’ works on executive-legislature relations in the EU corroborate this argument as well (Borrás and Radaelli Reference Borrás and Radaelli2011, p. 479). Formal rules in an institutional setting, therefore, determine the likelihood of who gets to be a policy entrepreneur.

Second, formal political institutions, such as vertical division of powers, factor in determining the likelihood of success of policy entrepreneurs. They do so by either presenting venues to them at the subnational level (typically in federal polities) or precluding their entrepreneurial activities at any venue other than the national capital (typically in centralised unitary polities). In the USA, for example, policy entrepreneurs advocating parents’ rights in school choice were able to capitalise on policy windows at the local level (Mintrom Reference Mintrom1997). This was made possible by the availability of funding at the local level for prospective policies entrepreneurs advocated (Mintrom Reference Mintrom1997, Reference Mintrom2019, p. 36). In Brazil, policy entrepreneurs, as leaders of the movimento sanitário, made the Brazilian healthcare system more universal and more decentralised by using subnational venues. They brought about change at the local level when they realised bringing about reform at the federal level was foreclosed (Falleti Reference Falleti2010). The literature provides many examples of successful entrepreneurs operating at the local level in federal polities in diverse policy areas (Kalafatis and Lemos Reference Kalafatis and Lemos2017; Mintrom and Luetjens Reference Mintrom and Luetjens2017). Policy entrepreneurs in centralised unitary polities would find it very difficult to push through their agendas and succeed at the local level.

Informal rules in different institutional settings shape who gets to be a policy entrepreneur and their strategies in different ways. First, policies, once institutionalised, distribute power among actors. They, therefore, select who gets to be an entrepreneur. Those who are empowered by institutionalised policies, such as policy entrepreneurs, have a greater chance to enjoy “authoritative voices” (Weir Reference Weir, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992, p. 192). These voices would be found convincing in the decision arena than their less authoritative counterparts. It is in this sense that recent research confirms that “past laws and institutional arrangements” empower some policy actors (Mintrom Reference Mintrom2019, p. 33). In Turkey, for example, past policies on the road to neoliberal restructuring allowed a World Bank Vice President to emerge as a policy entrepreneur. Turkey’s macroeconomic policies since the 1980s rendered this entrepreneur a legitimate and authoritative voice to bring about a series of reforms in the early 2000s (Bakir and Jarvis Reference Bakir and Jarvis2017). In cases where potential policy entrepreneurs are not positioned favourably like this empowered actor, they would still have to navigate within the contexts shaped by past policies. Policy entrepreneurs should, therefore, develop their strategies taking into account the structuring effects of long-established policies.

Second, informal rules shape the strategies policy entrepreneurs pursue in different geographies (Galanti Reference Galanti, Bakir and Jarvis2018; Mintrom Reference Mintrom2019, p. 21). Informal rules shaping their strategies, as highlighted in the literature, include “norms of acceptable behaviour”Footnote 9 of a given setting (Petridou and Mintrom Reference Petridou and Mintrom2020, p. 7). Norms of acceptable behaviour effectively constrain policy entrepreneurs’ actions regardless of whichever direction they may take. In Thailand, for instance, policy entrepreneurs, in order to reform local governance, had to present themselves as “the benevolent brother, with a responsibility to help those with limited resources” given the country’s long-established “hierarchical social system” (Chamchong Reference Chamchong2020, p.79). Likewise, in Israel, long-held “religious and national sensitivities” on the holly lands effectively constrained policy entrepreneurs by imposing an “incremental” approach to altering the settlements (Shpaizman et al. Reference Shpaizman, Swed and Pedahzur2016, p. 1049). These sensitivities rendered the option of abrupt displacement of existing policy on the status of Holy Basin of Jerusalem beyond the reach of any policy entrepreneur. Given the standard operating practices in the policy field, policy entrepreneurs had to resort to an incremental strategy of conversion. In these ways, informal rules such as “coalition building and networking” determine the strategies through which policy entrepreneurs pursue their reform agendas (Mintrom and Luetjens Reference Mintrom and Luetjens2017, pp. 1366–1373).

Conclusion

In this article, we aimed at exploring the politics of policy change by zooming in on the agenda-setting stage. Focusing on how the politics of agenda change is institutionally structured, we explored: Which institutions should we focus on when we study the politics of agenda setting in different geographies? How do they shape the structural elements problem stream, policy stream, political stream, policy windows, policy entrepreneur of MSA? In addressing our first question, we followed a fine-grained approach to institutions and listed examples of formal and informal rules playing key roles in agenda-setting processes.

In addressing our second question, we illustrate the ways in which formal and informal rules structure each founding element of MSA. First, in the problem stream, we show that institutions effectively shape the politics of problem definition in two ways. Formal rules in an institutional setting confer positional advantages to some actors and increase their chances to emerge as problem brokers. Informal rules shape whether and if so, how, and to what extent actors perceive, conceptualise, define, and construct conditions as problems. Second, zooming in on the policy stream, we illustrate that formal rules in given geography determine the location where policy community members venue shop and the degree of autonomy they enjoy from political administration. When it comes to informal rules, we explored how they shape the distribution of resources among policy communities by empowering some actors while disempowering others. Additionally, we learned that informal rules bias actors’ preferences and prejudices and filter viable policy alternatives in the policy stream. Third, focusing on the political stream, we show how formal rules configure power distributions among organised political actors in different institutional contexts. Formal rules also function to intermediate these actors. Moreover, they determine the timing and the ways in which key actors respond to changes in the national mood. Likewise, we learned that informal rules produce and reproduce the national mood. They also distribute power among organised political forces. Fourth, as to policy windows, we now know that formal rules in different geographies determine how long windows need to remain open for bringing agenda change. These rules also affect the extent to which spillover effects may open policy windows in other jurisdictions to produce changes in agendas. Informal rules determine whether windows open in the problem stream or the policy stream. Like formal rules, informal rules, too, affect how long windows need to remain open for policy action. Fifth, in terms of policy entrepreneurs, we show how formal rules select the venues in which policy entrepreneurs should operate and shape the chances of their success. Informal rules determine who gets to be an entrepreneur in a given geography. They also heavily shape their entrepreneurial strategies in bringing about agenda change.

This article, in this way, explored how institutions play key roles in structuring the politics of policy change through the powerful lens of MSA. It drew on the powerful insights of two bodies of literature, comparative public policy, and comparative politics, which we believe have much to learn from one another. Comparative public policy provides us with an intuitive tool, MSA, which helps us explore who gets what, when, and how in the policy process. In doing so, it equips us with a clear template to analytically dissect the politics of the policy process starting from the agenda-setting stage. Comparative politics, with its due focus on a wide range of institutions, guides us in exploring “who can play and how they play” (Steinmo Reference Steinmo2015, p. 181) in policy change. This literature allows us to pursue a fine-grained strategy towards institutions in discovering how the politics of policy change is institutionally structured in space and time (Hall Reference Hall, Fioretos, Falleti and Sheingate2016).

Bringing together these two bodies of literature, we believe, will allow us to weave institutions into MSA’s backbone more tightly. We thus hope we gain some mileage in responding to authoritative voices’ calls for bringing institutions into theories of the policy process in general and MSA in particular. By signposting a set of key formal and informal rules, structuring the politics of policy change in different institutional settings, we hope we will produce more comprehensive and systematic comparisons.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Emina Hasanagic, Ali Berk İdil, and two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and incisive and stimulating comments on the earlier versions of this article. We also would like to thank the convenors, discussants, and participants of the panel “The Multiple Streams Framework: Theoretical Refinements and Empirical Applications” at the 5th International Conference on Public Policy, Barcelona, 2021. This article draws, in part, from the research Deniz Yıldırım's doctoral project in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at Bilkent University.

Competing interest declaration

The author(s) declare none.

Funding information

This research was supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK) under Grant number 115.02-166509 and TÜBİTAK under Grant number 109K443.

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.

H. Tolga Bolukbasi is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at Bilkent University.

Deniz Yıldırım is an Instructor (part-time) in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at Bilkent University.