Introduction

The existing publications about healthcare reform are mainly from developed countries, with a shortage of information from developing countries (Arrow et al., Reference Arrow, Auerbach, Bertko, Brownlee, Casalino, Cooper, Crosson, Enthoven, Falcone, Feldman, Fuchs, Garber, Gold, Goldman, Hadfield, Hall, Horwitz, Hooven, Jacobson, Jost, Kotlikoff, Levin, Levine, Levy, Linscott, Luft, Mashal, McFadden, Mechanic, Meltzer, Newhouse, Noll, Pietzsch, Pizzo, Reischauer, Rosenbaum, Sage, Schaeffer, Sheen, Silber, Skinner, Shortell, Thier, Tunis, Wulsin, Yock, Nun, Bryan, Luxenburg and van de Ven2009). In some systematic reviews about healthcare reform, the requirement for the full text to be available in English has excluded many documents from developing countries, especially those without English as a native language, although the inclusion criteria usually include studies from low- or middle-income countries (Dickersin, Reference Dickersin2010; Robert et al., Reference Robert, Annette, Elizabeth, Varnee, Jesper, Arvind, Frank, Adriano, Brandi, Andrey and Ronald2010; Balkrishnan et al., Reference Balkrishnan, Chang, Patel, Yang and Merajver2013). Health affairs in developing countries tend to be more difficult than in developed countries, as the former are often less advanced socioeconomically, scientifically and technologically. Accordingly, healthcare reform in developing countries is more complex than in developed countries. They need help from developed countries but in turn, may inspire the developed countries to make further reforms.

China is the largest developing country. Although there are many shortcomings in China’s healthcare system, there have also been some positive results in terms of population health, such as an average life expectancy of 74.83 years and infant mortality rate of 13.93‰ in 2010 (National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, 2010). More importantly, these achievements were made from a state of ‘poverty and blankness,’ with shortages of medical services and medicines. According to the health services comparative research of Shanghai County, China and Washington County, USA (1981), the life expectancy improvement of Shanghai County from 44.7 years old to 72.4 years old took 30 years (from 1950 to 1980), and those of Washington County from 49.2 years old to 73.2 years old took 80 years (from 1900 to 1980). The mortality rate of infant and the general population of Shanghai County in 1980 were 14.8‰ and 6.2‰, respectively; with 27 RMB per capita health costs, and those of Washington County were 16.3 and 9.5‰, respectively; with 885 Dollar per capita health costs (Lu, Reference Lu2003; Li, Reference Li2007).

China’s experience has been highly praised by the World Health Organization (WHO), and recommended to other countries. As the most generalized information currently available, China’s National Health Guiding Principles (CNHGP) are perhaps among the most valuable and worthy of sharing. This article provides a profile of CNHGP, and highlights their value for healthcare reform. The aim of this article is to provide a new perspective on international healthcare reform.

The history of CNHGP

CNHGP is a product of the collective wisdom of health professionals and statesmen and has been in place throughout the 60 years since the end of the Chinese Civil War and the period of socialist construction (Hu and Liu, Reference Hu and Liu1993). In 1950, the second year after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the first national health conference was held, and the new government introduced the preliminary national health guiding principles. These were:

-

∙ the workers, farmers and soldiers (in essence, the masses or grassroots) are the top priority;

-

∙ disease prevention must be placed first; and

-

∙ Chinese traditional medicine and Western medicine must work together.

Two years later, at the second national health conference held in 1952, Mao Zedong, the first Chairman of The People’s Republic of China, proposed an additional guiding principle – that health affairs must be driven by mass participation, linked to the principle of coming from the masses and going back to the masses, or for the masses and by the masses in the Chinese Communist Revolution. These four health principles persisted into the 1990s (Lan, Reference Lan1998). Guided by these, China’s government made remarkable achievements in the health field under poor economic conditions. The average life expectancy increased from 35 years in 1949 to 68 years in 1980, higher than the average life expectancy during the same period globally (61 years) or in middle-income countries (64 years) (Wang, Reference Wang2003; Wagstaff et al., Reference Wagstaff, Yip, Lindelow and Hsiao2009).

At the 1996 national health conference, China’s government put forward the following national health guiding principles:

-

∙ people in rural areas are the top priority;

-

∙ disease prevention must be placed first;

-

∙ Chinese traditional medicine and Western medicine must work together;

-

∙ health affairs must depend on science and education; and

-

∙ society as a whole should be mobilized to participate in health affairs, thus contributing to the people’s health and the country’s overall development.

The principle that ‘people in rural areas are the top priority’ originated from ‘the masses are the top priority,’ because China is still essentially an agricultural country. That ‘the whole society should be mobilized to participate in health affairs’ emerged from ‘health affairs must be driven by mass participation.’ These principles have been maintained to date, and are predicted to have important, far-reaching and long-lasting effects on Chinese health in the 21st century and possibly beyond.

The value of CNHGP for healthcare reform

For countries faced with much talk but little action on healthcare reform, CNHGP, with its 60-year history, may provide a new perspective (Fuchs, Reference Fuchs2009; Duncan, Reference Duncan2013). Because of the complexity of healthcare systems, healthcare reform needs to learn from experience and politics (Ross, Reference Ross2009; Duncan, Reference Duncan2013). As the product of the collective wisdom of health professionals and statesmen, CNHGP may provide particular value. It is worth noting that since the reform and opening up of China, especially in the last 10–20 years, China has imported advanced Western medical science, technology and management experience while ignoring its own effective methods of healthcare, and to some extent, even devaluing them. Nowadays, in China, CNHGP does not get the recognition and further development that it perhaps deserves, and its contribution has not been analyzed in any depth. We believe that there are four values of CNHGP for healthcare reform.

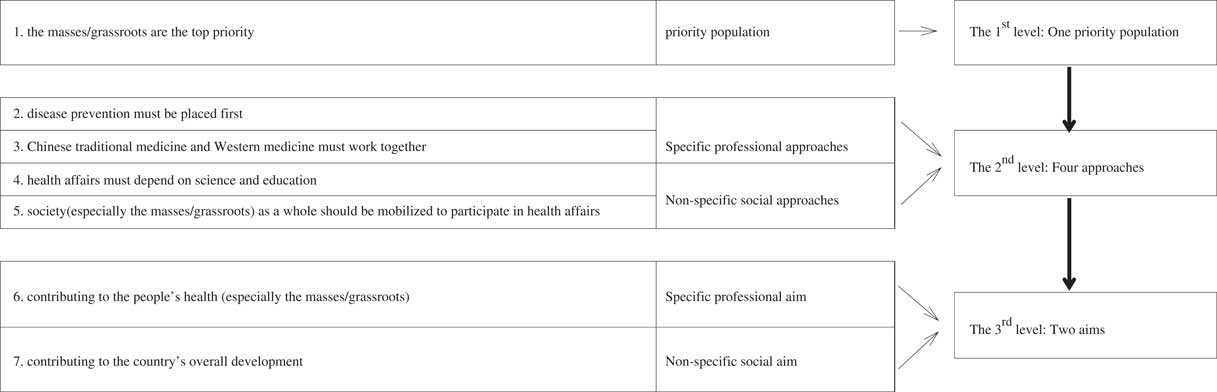

First, these principles provide an innovative strategic framework for healthcare reform with three levels, from ‘One priority population’ to ‘Four approaches’ and then to ‘Two aims’ (Figure 1). Nowadays, the chief difficulty encountered in healthcare reform is the lack of systematic guiding principles that can inform strategic frameworks for policy-making, practice and evaluation, a gap that could be filled by CNHGP.

Figure 1 Logical structure of China’s National Health Guiding Principles

The second is the importance of mass/grassroots participation, which runs through all three levels of CNHGP. The Cooperative Medical Scheme (CMS), which has widely benefited farmers in rural China and was highly praised by the World Bank and WHO in the 1960 and 1970s, could provide an example of successful focus on the masses (World Bank, 1981; Sidel, Reference Sidel1982). According to the Ministry of Health in China, the essence of the CMS, just as its name suggests, is cooperation between healthcare staff and farmers focused on the health-related risks associated with agricultural work and the farmer’s way of life (China’s Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme Act, 1979). In other words, this cooperation places responsibility at least partly on the farmers and agricultural workers, and not solely on healthcare staff (Wang and Liang, Reference Wang and Liang2017). However, China’s New Rural CMS, which was launched in 2003 as a new health insurance program covering the rural population, deviates somewhat from the original idea and principle (Yip and Hsiao, Reference Yip and Hsiao2009; Yang, Reference Yang2013).

In fact, the idea of mass/grassroots participation is not limited to China. As early as 1994, researchers in the United States proposed grassroots participation, and believed that it was a pattern of development that could prove helpful to reformers, users, and providers of healthcare services (Crawshaw, Reference Crawshaw1994). Although the terms social participation and public involvement are now more commonly used, their essence is the same (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman2003; Contandriopoulos, Reference Contandriopoulos2004; Fleury, Reference Fleury2011). The idea is widespread, but it is worth noting that there is one key difference between the Western and Chinese ideas of mass participation: the Chinese focus was on the mobilization of the masses to address health-related risks, while the western idea was perhaps more designed to overcome opposition from special interest groups. Mass participation in China might provide extended coverage and improved quality, while also making coverage more affordable, which would be very helpful for healthcare reform (Brook, Reference Brook2009).

The third value is that the CNHGP used nonspecific social approaches, an innovation in healthcare delivery that addressed the social determinants of health. As Figure 1 shows, specific professional approaches and nonspecific social approaches are two parallel options for managing health affairs. An immunological phenomenon may help us to understand the relationship between them. Specific professional approaches would be analogous to ‘specific immunity’ and nonspecific social approaches would be analogous to ‘nonspecific immunity.’ Nonspecific immunity is essential for human immunology, and similarly, nonspecific social approaches may also be essential for healthcare. Existing studies about healthcare reform always emphasize the power of the government and markets (Bamford and Porter-O’Grady, Reference Bamford and Porter-O’Grady2000; Schlesinger, Reference Schlesinger2002; Burström, Reference Burström2009; Tang, Reference Tang2013; Çiçeklioğlu et al., Reference Çiçeklioğlu, Öcek, Turk and Taner2015; Maarse et al., Reference Maarse, Jeurissen and Ruwaard2015). However, given the social determinants of health, the power of nonspecific social approaches, such as community involvement, as well as science and education have perhaps not been sufficiently emphasized. Very few comparisons between the two approaches have been made, and this may be worth further study in the future. Good healthcare is not only a matter of medicine, but also a product of the organization of care and social approaches (Lantz et al., Reference Lantz, Lichtenstein and Pollack2007; Duncan, Reference Duncan2013).

The fourth value is the integration between Chinese traditional medicine and Western medicine. From a global perspective, this approach would be the integration of complementary/alternative medicine (CAM) and Western modern medicine. Chinese traditional medicine has been in a weak position, since Western medicine came to China about 100 years ago. At present, although the modernization of Chinese medicine encountered a lot of difficulties and obstacles, and also by some scholars questioned, it has more than 3000 years of history, which guarantees the Chinese nation for thousands of years of national reproduction and civilization development. It is worth noting that the people’s acceptance of Chinese traditional medicine showed a slight upward trend in the last 30 years. Especially, the ratio of the number of visits per year of Western medicine/those of Chinese traditional medicine every five years from 1980 to 2000 was 10.45, 5.84, 3.42, 3.03 and 3.21, respectively (National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, 2004). Additional, CAM were widely used around the world, such as 52.2% of the population in Australia (MacLennan et al., Reference MacLennan, Myers and Taylor2006), 40% of adults in the United States (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Bloom and Nahin2008), 33.8% of cancer patients in Turkey (Üstündağ and Demir, Reference Üstündağ and Demir2015), 44.6% of cancer patients in Japan (Shumer et al., Reference Shumer, Warber, Motohara, Yajima, Plegue, Bialko, Iida, Sano, Amenomori, Tsuda and Fetters2014), 33.8% of cancer survivors in Norway (Kristoffersen et al., Reference Kristoffersen, Norheim and Fønnebø2013) and 57% of children in Germany (Gottschling et al., Reference Gottschling, Gronwald, Schmitt, Schmitt, Längler, Leidig, Meyer, Baan, Shamdeen, Berrang and Graf2013). Furthermore, the integration between CAM and Western medicine needs to play their own strengths. Perhaps, Western medicine would need to provide acute and severe services, such as organ transplantation, reproductive technology and traumatology and CAM would need to provide primary healthcare (Zhang and Hui, Reference Zhang and Hui2015).

In summary, international discussion and debate on essential healthcare reform is important involving the participation of developing countries. CNHGP provided a valuable framework for developing countries with four values, namely the innovative strategic framework for healthcare reform with three levels from ‘One priority population’ to ‘Four approaches’ and then to ‘Two aims;’ the mass/grassroots participation; the innovation in healthcare delivery addressed the social determinants of health; and the integration between CAM and Western medicine.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank National Natural Science Foundation of China for funding this study. The authors acknowledge the valuable comments of the anonymous PHCRD reviewer.

Financial Support

This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71273098). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

None.