The application of life course and osteobiography approaches to the remains of individuals in the archaeological record allows researchers, in more fluid and holistic ways, to begin reconstructing who those individuals were as people, some of their life experiences, and how they were treated and remembered by their family at death. Inspired by these approaches, this article applies a multifaceted methodology that draws on osteological, archaeological, and epigraphic data to gain a better understanding of the life and death of an individual buried at the Maya site of El Palmar, Mexico. Epigraphic studies suggest that this individual had the title of lakam (“banner” in Colonial Yukatek Maya; thus, a “standard-bearer”), an important political position during the Late Classic period (AD 600–800).

In ancient Mesoamerica, standard-bearers played crucial political and economic roles (Braswell Reference Braswell, Smith and Berdan2003; Houston and Stuart Reference Houston, Stuart, Inomata and Houston2001; Lacadena Reference Lacadena2008; Palka Reference Palka2014; Rice Reference Rice2007; Tsukamoto and Esparza Olguín Reference Chase, Chase, Demarest, Rice and Rice2004). Nevertheless, their life history and physical characteristics have remained unknown, mainly because few burials of known standard-bearers have been found in the archaeological record. An exceptional case is El Palmar where we find long inscriptions that depict genealogical ties between standard-bearers and its north plazuela group (Tsukamoto et al. Reference Tsukamoto, Camacho, Valenzuela, Kotegawa and Olguín2015). This article demonstrates how a multifaceted approach can, through several lines of evidence, provide a holistic view of changing identities over time at an individual level.

Life Course and Osteobiography

Life course analysis combines concepts and methods from disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, psychology, and history (Inglis and Halcrow Reference Inglis, Halcrow, Beauchesne and Agarwal2018). This approach has gained popularity in bioarchaeological studies because it more holistically connects individuals with the historical and socioeconomic contexts in which they lived (Agarwal Reference Agarwal2012; Elder et al. Reference Elder, Johnson, Crosnoe, Mortimer and Shanahan2004; Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2012; Glencross Reference Glencross, Agarwal and Glencross2011; Knudson and Stojanowski Reference Knudson and Stojanowski2008). A critical aim of the approach is to understand the human life experience as a continuum, rather than compartmentalizing the analysis into datasets that correspond to successive segmented stages of life, such as infancy, childhood, adolescence, or old age (Inglis and Halcrow Reference Inglis, Halcrow, Beauchesne and Agarwal2018).

Contextualization of gender and aging has been crucial in the development of the life course approach within archaeology and bioarchaeology. For example, researchers have examined the differences between physiological, chronological, and cultural ages within a group and the relationship between biological sex, as well as the cultural construction of gender (e.g., Agarwal Reference Agarwal2012; Beauchesne and Agarwal Reference Beauchesne and Agarwal2018; Geller Reference Geller2009, Reference Geller2018; Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1999; Glencross Reference Glencross, Agarwal and Glencross2011; Hollimon Reference Hollimon, Agarwal and Wesp2017). Others have studied disability, disease, and social inequalities (Byrnes and Muller Reference Byrnes and Muller2017; Hawkey Reference Hawkey1998; Roberts Reference Roberts1999; Tilley and Oxenham Reference Tilley and Oxenham2011).

The body has also been a central focus of investigation in an attempt to bridge theoretical and methodological divisions between the study of human remains and socially informed archaeological interpretations of the past (Hollimon Reference Hollimon, Agarwal and Wesp2017). Sofaer (Reference Sofaer2006) emphasizes that the body is socially constructed and should be conceptualized as the union between the biological and material bodies. Archaeologists and bioarchaeologists have used embodiment theory to understand social constructions of the body, how individuals used their bodies, and how the body was perceived by past populations (Fisher and Loren Reference Fisher and Loren2003; Joyce Reference Joyce and Chesson2001, Reference Joyce2005; Meskell Reference Meskell1999; Meskell and Joyce Reference Meskell and Joyce2003; Perry and Joyce Reference Perry and Joyce2001). Embodiment describes how the physical body is shaped and how habits and practices are inscribed on the skeleton over the course of life through complex interactions between an individual's biology and the social context (Hollimon Reference Hollimon, Agarwal and Wesp2017; Joyce Reference Joyce and Chesson2001, Reference Joyce, Nelson and Rosen–Ayalon2002). Several researchers have juxtaposed identity and embodiment using a variety of data from the archaeological record (Fisher and Loren Reference Fisher and Loren2003; Joyce Reference Joyce2005; McClelland and Cerezo-Román Reference McClelland, Cerezo-Román, Giles and Williams2016; Meskell Reference Meskell1999; Meskell and Joyce Reference Meskell and Joyce2003; Perry and Joyce Reference Perry and Joyce2001). Those using a life course approach at the population level have been successful in exploring the biological body and the social body (e.g., Agarwal Reference Agarwal2012; Agarwal and Wesp Reference Agarwal and Wesp2017; Beauchesne and Agarwal Reference Beauchesne and Agarwal2018; Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2000; Gowland Reference Gowland, Gowland and Knüsel2006; Sofaer Reference Sofaer2006). Nevertheless, the application of this approach at the individual level is challenging. Through applying osteobiographic principles in conjunction with embodiment and the life course approach, we attempt to overcome some of the difficulty in reconstructing individual life histories.

Inspired by Krogman's identification methods of human remains (Buikstra Reference Buikstra, Buikstra and Beck2006; Krogman Reference Krogman1935), Frank and Julie Saul (Saul Reference Saul1972; Saul and Saul Reference Saul, Saul, Yasar İşcan and Kennedy1989) introduced the term “osteobiography.” This approach primarily stresses methodology and involves collecting data about demography or functional adaptations and pathologies from individual skeletons. The goal is to identify the individual biological profile in order to address questions ranging from health, diet, and occupation to the status of women in the past (Buikstra Reference Buikstra, Buikstra and Beck2006; Buikstra and Scott Reference Buikstra, Scott, Knudson and Stojanowski2009; Geller Reference Geller2012; Watson and Stoll Reference Watson and Stoll2013). Following Saul (Reference Saul1972; see also Saul and Saul Reference Saul, Saul, Yasar İşcan and Kennedy1989) and Hawkey (Reference Hawkey1998), Stodder and Palkovich (Reference Stodder and Palkovich2012) emphasize the osteobiographical approach as a useful methodological and theoretical framework for understanding the life history of individuals.

Subsequently, these ideas were expanded and elaborated on by considering the connection of the individual to the broader group, moving away from a strictly descriptive and functional approach. For example, several researchers (e.g., Grosman et al. Reference Grosman, Munro and Belfer-Cohen2008; Voss Reference Voss, Casella and Fowler2005; Whelan Reference Whelan1991) used the osteobiographical method to analyze specific individuals within a group. Robb (Reference Robb, Hamilakis, Pluciennik and Tarlow2002) proposed that osteobiography should be treated as a cultural narrative or story of a person that stresses the past life events of individuals and the postdepositional processes affecting their remains. Geller (Reference Geller2012) and Geller and Suri (Reference Geller and Suri2014), in contrast, emphasize life and death histories to examine the identities of individuals. Geller developed the concept of “death history” to describe the community's ongoing engagement with decedents’ bodies and to better understand how individuals experience the world during life and death (Geller and Suri Reference Geller and Suri2014). Whereas some researchers include death histories in their osteobiographical analyses (Mayes and Barber Reference Mayes and Barber2008), others focus only on individual biological and life experiences (Alfaro Castro et al. Reference Castro, Martha Elena, Waters-Rist and Zborover2017; Lessa and Guidon Reference Lessa and Guidon2002).

Inspired by the life course and osteobiographical approaches, this article analyzes an individual recovered from Burial 1 at El Palmar to assess who he was, some of his personal life experiences, and how he was treated and remembered at death by family members, mourners, and the broader community. We reconstruct the life history and osteobiography of this individual by combining data from the skeleton and his treatment at death with the archaeological and epigraphic data. Then, we discuss some issues we confronted in the research while attempting to reconstruct the life course of an individual as a continuum.

El Palmar

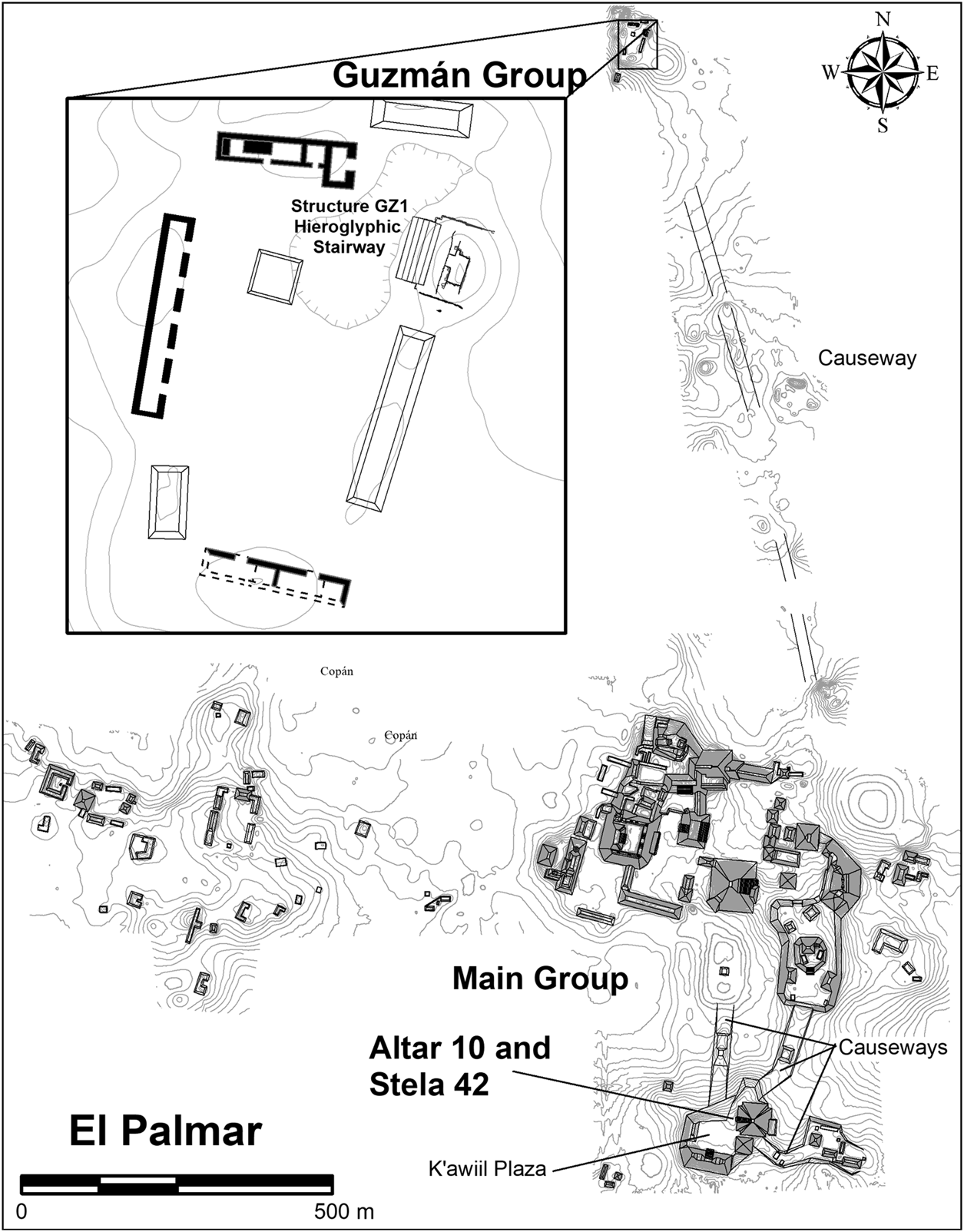

El Palmar is located at the eastern edge of the Central Karstic Uplands of the Yucatan Peninsula (Figure 1). Surrounding El Palmar are other large sites such as Tikal and Calakmul, the latter of which became the capital of the Snake Dynasty after AD 635 (Helmke and Awe Reference Helmke and Awe2016; Martin and Velásquez García Reference Martin and García2016). El Palmar was occupied from the Late Preclassic to the Terminal Classic period (ca. 300 BC–AD 850), with an urban transformation occurring during the Middle Classic (AD 400–600; Tsukamoto Reference Tsukamoto, Tsukamoto and Inomata2014). Epigraphic studies revealed El Palmar's dynastic history from AD 554 to 820, including political interactions with Calakmul (Esparza Olguín and Tsukamoto Reference Esparza Olguín, Tsukamoto, de Velasco and Vega2011).

Figure 1. Map of Yucatan Peninsula showing the location of El Palmar and other archaeological sites.

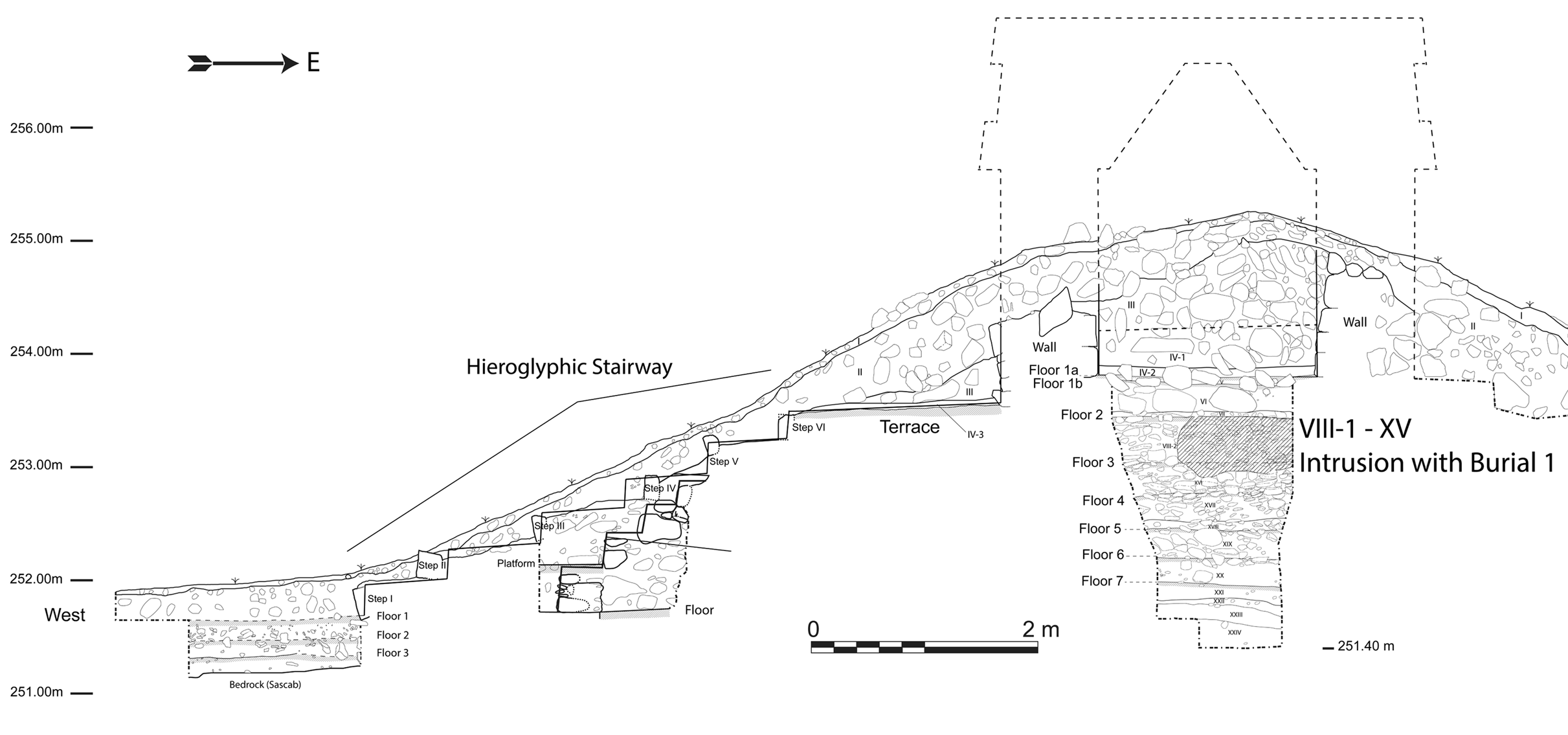

During the 2009 field season, Tsukamoto documented the Guzmán Group, an outlying plazuela (a small plaza compound) located 1.3 km north of the Main Group. It comprised a small plaza surrounded by a temple (Structure GZ1) at its east end and six rectangular structures on the other sides (Figure 2). This particular spatial configuration is a typical layout known as Plaza Plan 2 in the Maya Lowlands (Becker Reference Becker1991; Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Demarest, Rice and Rice2004). The eastern temples usually have a burial, and researchers have interpreted the individuals inside the burials as ancestors of the social groups who occupied these plazas (McAnany Reference McAnany1995). Extensive excavations revealed that the Guzmán Group began with scattered modest houses with chultunob by cal AD 321; it was transformed into a plazuela group by cal AD 682, serving as a location for administrative, ceremonial, and domestic activities (Tsukamoto et al. Reference Tsukamoto, Fuyuki Tokanai and Nasu2020). The excavations at Temple GZ1 exposed a hieroglyphic stairway that was built in AD 726 (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Map of the Main Group and the Guzmán Group at El Palmar.

Figure 3. Excavated section of Structure GZ1 with the location of Burial 1.

The inscriptions depict a standard-bearer who played the role of ambassador in negotiating political alliances between El Palmar, Copán, and Calakmul (Tsukamoto and Esparza Olguín Reference Tsukamoto, Olguín, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2015). In prehispanic Mesoamerica, standard-bearers were frequently depicted in procession, tributary, and ceremonial scenes on carved monuments, murals, and polychrome vessels and in graffiti (e.g., Kerr Reference Kerr1998:K680). Different lines of evidence including iconographic images suggest that they played important roles in constituting Mesoamerican polities. Among some of the earliest known examples are an Olmec carving on Monument 13 at La Venta, which shows a walking nobleman called the “Ambassador” (Rice Reference Rice2007:96–97) or the “Walker” (Palka Reference Palka2014:125). In this carving, a footprint or travel/arrival glyph appears alongside a person carrying a banner and arriving on foot to the site to participate in a ritual (Palka Reference Palka2014:125). Historical accounts of lolmay or lolmet, the K'iche’ name for ambassador, describe the importance of these type of nonroyal elites who served as intermediaries in negotiating political alliances between rulers (Braswell Reference Braswell, Smith and Berdan2003).

Temple GZ1's text documents an individual, Ajpach’ Waal, who was a descendant of standard-bearers (for more detailed information, see Tsukamoto and Esparza Olguín Reference Tsukamoto, Olguín, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2015). It commemorates his journey to the kingdom of Copán located 350 km to the south of El Palmar. On June 25, AD 726, he was allowed to meet Waxaklajuun Ubaah K'awiil, Copán's thirteenth ruler. This event occurred most likely under the auspices of Calakmul (i.e., the Snake Dynasty), because one of its kings, Yuknoom Took’ K'awiil, also appears in the texts. Three months later on September 13, AD 726 (or 9.14.15.0.0), Ajpach’ Waal built the stairway, claiming his ownership of the temple and presumably of the entire Guzmán Group by listing his genealogical tie to lakam ancestors from his father, Ajlu…Chih, to his great-grandfather. The word lakam means banner in Colonial Yukatek Maya, and therefore people who hold the lakam title are considered standard-bearers. Some painted vessels depict lakam elites (or lakamob) in tributary and processional scenes (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston, Stuart, Inomata and Houston2001; Lacadena Reference Lacadena2008; Stuart Reference Stuart2010). The genealogical list on the inscriptions probably indicates that the standard-bearers lived in the Guzmán Group for generations, which was common practice in ancient Maya society (McAnany Reference McAnany1995). In addition to the historical event and the genealogical list of standard-bearers, the center of the second step shows iconographic images of a large ball flanked by two ballplayers. The stairway was almost intact, meaning that it was most likely found in situ with minimum pre- and postabandonment alterations.

Stratigraphic excavation at a temple in its north architectural group uncovered a burial (Burial 1) containing an individual with two polychrome vessels as offerings (Tsukamoto et al. Reference Tsukamoto, Camacho, Valenzuela, Kotegawa and Olguín2015). The individual is either Ajpach’ Waal, who owned both the hieroglyphic stairway attached to the temple and presumably the entire Guzmán Group, or his father Ajlu…Chih, who also appears to have been a standard-bearer. This exceptional finding helps us piece together the life history of Classic period Maya standard-bearers.

Burial 1 Analysis Results

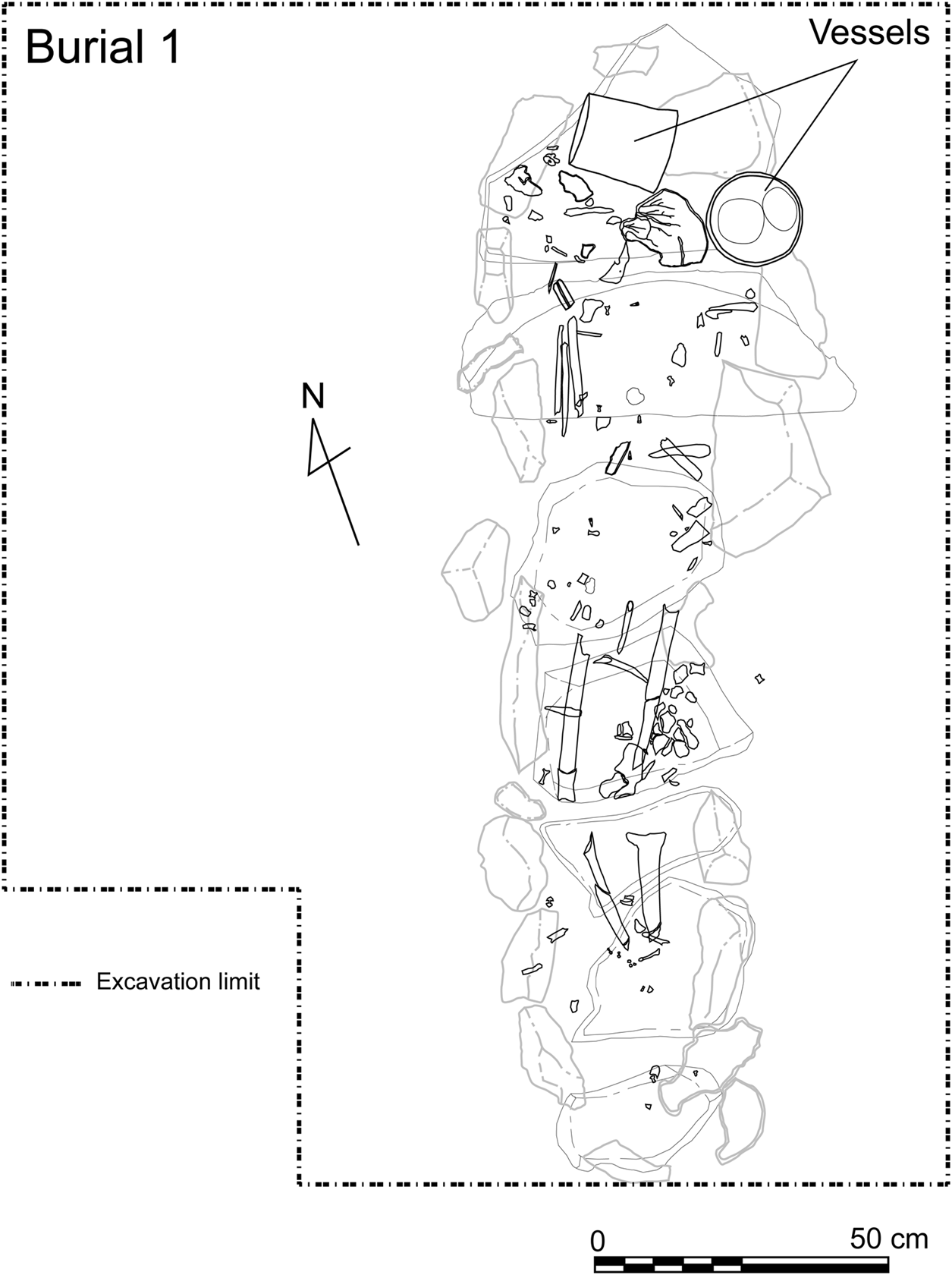

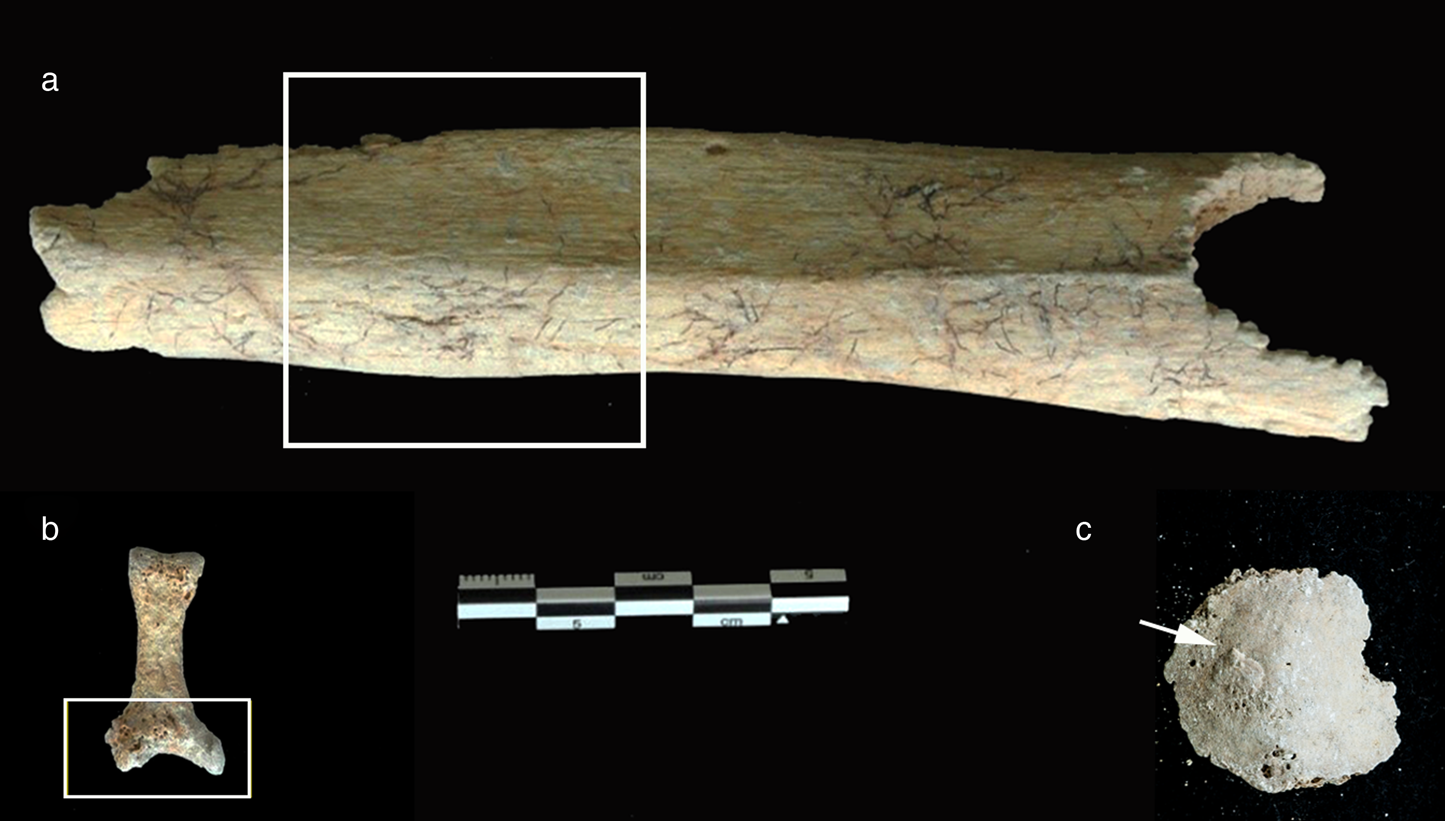

The primary inhumation burial (Burial 1) was found in a cist located underneath the floor of the upper shrine. The cist, which measures 2 m long, intrusively cuts into the fill of the previous plaster floors and was formed by seven stone slabs aligned from north to south. The individual lay extended with the head positioned toward the north. The bones were in relative anatomical position, and the degree of articulation suggests that the body decomposed in situ (Figure 4). The cist created a space that allowed minor movement of the skeletal elements as the body decomposed (Duday Reference Duday2009). There is no archaeological evidence that the grave was ever reopened. The bones received minor biodisturbances from small animals such as rodents, soil, and plant roots.

Figure 4. Burial 1.

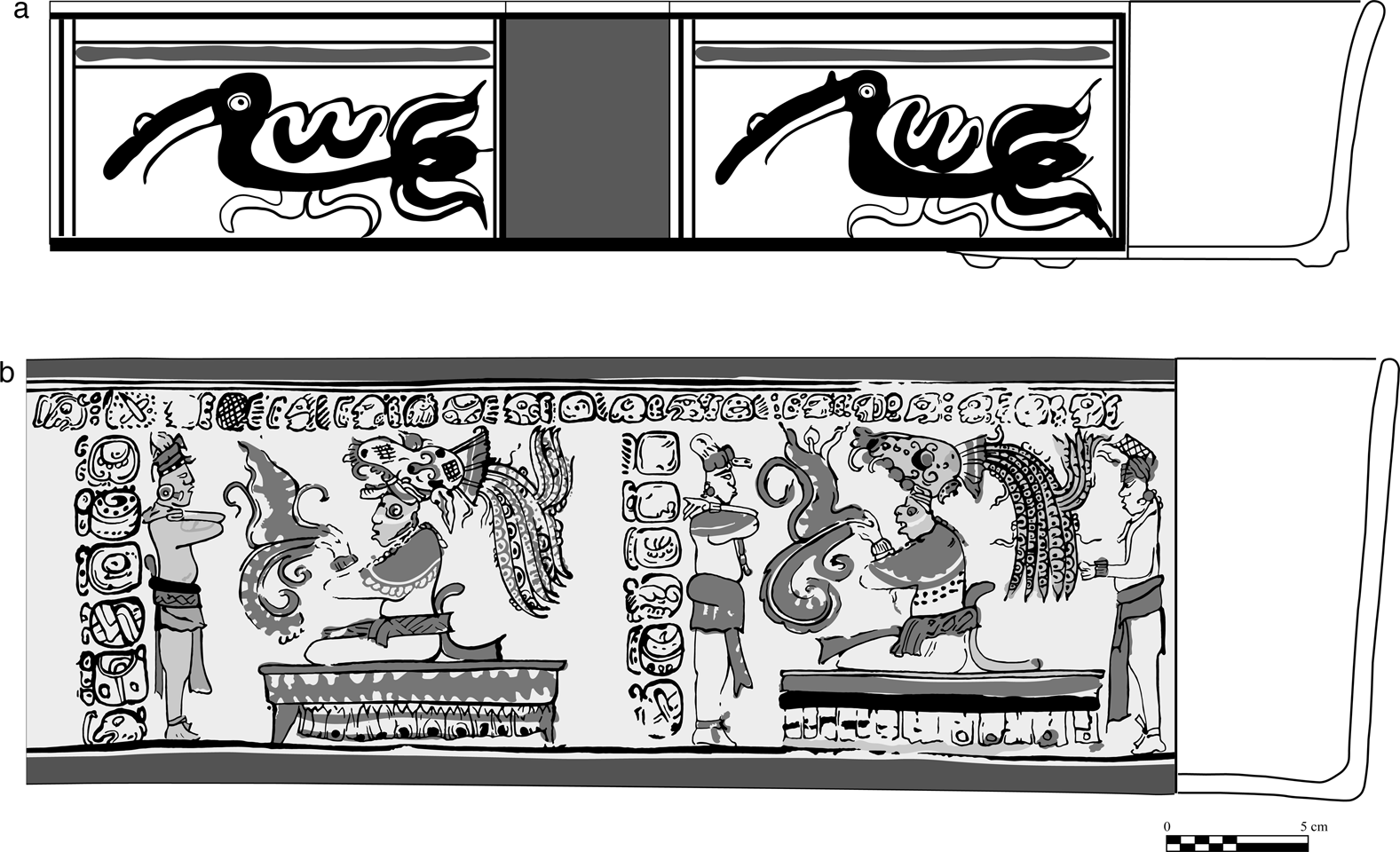

Two polychrome vessels were placed at the north end of the cist as a mortuary offering. Although Tsukamoto mentioned these vessels elsewhere (Tsukamoto et al. Reference Tsukamoto, Camacho, Valenzuela, Kotegawa and Olguín2015:207–208), it is worth describing their iconographic representations here because of their relation to the individual. The first vessel is a tripod bowl that depicts a bird on two sides with black feathers, a cormorant-like beak, and heron-like eyes that may represent an aquatic bird (Figure 5a; Schele and Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986:55). The second one is a cylinder vase that represents two mythological scenes of the fire ritual (Figure 5b). In each scene an individual with a luxurious headdress sits on a decorated bench. Flames or smoke issues from the hands of the main individual, and a servant stands in front of (and in one case also behind) the individual; three bands of pseudo-glyphs are drawn on the upper register and in between the scenes. Two radiocarbon dates, in concordance with stratigraphic relations and ceramic types, suggest that the burial was interred around AD 726 when the stairway was constructed (Table 1; Tsukamoto et al. Reference Tsukamoto, Camacho, Valenzuela, Kotegawa and Olguín2015).

Figure 5. Rollout drawings of polychrome vessels recovered from Burial 1: (a) Zacatel Cream Polychrome tripod bowl (drawing by Kenichiro Tsukamoto); (b) Saxche Orange Polychrome cylinder vase (drawing by Daniel Salazar Lama and Kenichiro Tsukamoto).

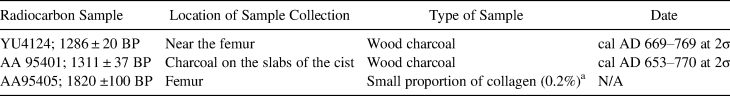

Table 1. Radiocarbon Dates, Location, and Sample Information.

aPossible imprecise dating due to the small proportion of collagen in the femur, although we do not entirely preclude this date as valid (Oxcal v. 4.3.2; Ramsey Reference Ramsey2017; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Warren Beck, Blackwell, Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Lawrence Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Felix Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Marian Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

Preservation of the skeletal remains allowed us to assess the sex of the individual, the age at death, some pathological conditions, and cultural modifications. Cranial, appendicular, axial, and extremity skeletal elements were identified and documented using osteological recording protocols proposed by Buikstra and Ubelaker (Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994) and the Arizona State Museum (Reference Museum2018). Burial 1 was male and between 35 and 50 years old when he died (see Supplemental Text 1 for the details of our osteological analysis).

Oral pathologies include dental calculus, hypercementosis on the maxillary right first incisor, an abscess possibly associated with the mandibular right first premolar, and extensive antemortem tooth loss on the left side of the mandible with considerable alveolar reabsorption (Figure 6). The teeth featured inlays from the right to left maxillary canine, classified as type E1 with dental alterations of the enamel (Romero Molina Reference Romero Molina and Stewart1970; Tiesler et al. Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Ramírez-Salomon, Burnett and Irish2017; Williams and White Reference Williams and White2006). Tabular cranial modification was observed on the occipital bone; because the frontal area was not completely preserved, it is not certain whether cranial modification was present on the forehead.

Figure 6. Mandible with antemortem loss of teeth and extensive alveolar reabsorption, calculus on maxillary right canine (#6), and dental modifications. (Color online)

Additionally, the individual exhibited microporosity on the ectocranial surface in the left and right parietal, which is related to mild porotic hyperostosis (Supplemental Text 1). We also found a minor healed periosteal reaction on the radii, as well as a healed fracture on the distal midshaft of the right tibia (Figure 7a). Light to moderate degenerative joint disease was recorded on the carpal phalanges of one hand (side unknown), right ulna, left femur, and left patella, as well as on the proximal and distal tarsal phalanges (Figure 7b and 7c).

Figure 7. (a) Right tibia with healed fracture; (b) small deposits of bone in tarsal phalange; and (c) left patella small surface osteophyte. (Color online)

Reconstructing the Life Course of the Individual in Burial 1

A multifaceted approach allowed us to reconstruct aspects of the individual's life and how he was treated and remembered by the mourners and community in death. Simultaneously, we recognize that there exist limitations on the amount of information that the analysis of the human remains, archaeological context, and epigraphic evidence can provide, especially when studying a single individual and trying to elucidate his entire life course. Nevertheless, it is possible to infer some of the life history of this individual from early infancy to death.

The individual in Burial 1 at El Palmar allows us to broaden our understanding of nonroyal elites. He had mild porotic hyperostosis, which is a nonspecific health indicator often associated with childhood disease (Plumer Reference Plumer2017). Specifically, it articulates with megaloblastic and hemolytic anemias, as well as scurvy (Ortner and Ericksen Reference Ortner and Ericksen1997; Ortner et al. Reference Ortner, Whitney Butler and Milligan2001; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Bathurst, Rebecca Richman and Andrushko2009; Zuckerman et al. Reference Zuckerman, Garofalo, Frohlich and Ortner2014). In the Americas, Walker and colleagues (Reference Walker, Bathurst, Rebecca Richman and Andrushko2009) suggest that this condition is commonly due to megaloblastic anemia caused by dietary deficiencies and malabsorption of vitamins B12 or folic acid. Other hematological and radiographic studies also indicate deficiencies in iron and vitamins A, B12, B6, and B9 (Rivera and Mirazón Lahr Reference Rivera and Lahr2017). This sort of bone modification can result from any combination of inadequate diet, a heavy reliance on maize, poor sanitation, diarrhea, intestinal parasites, infectious disease, cultural practices related to breastfeeding in childhood, or even in utero conditions (Walker et al. Reference Walker, Bathurst, Rebecca Richman and Andrushko2009). The frequency of porotic hyperostosis in Maya samples varies (e.g., subadults versus adults, core versus periphery), but its presence is common at low rates in sites such as Cuello, Iximché, Lamanai, and Tipu and at high rates in sites such as Chichén Itzá and Copán (e.g., Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1997; Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, O'Connor, Danforth, Jacobi, Armstrong, Whittington and Reed1997; Geller Reference Geller2012; Hooton Reference Hooton, Hay, Linton, Lothrop, Shapiro and Vaillant1940; Saul Reference Saul1972; Saul and Saul Reference Saul, Saul, Yasar İşcan and Kennedy1989; Storey et al. Reference Storey, Márquez, Schmidt, Steckel and Rose2002; Wright Reference Wright1994).

Although it is difficult to ascertain definitively what role the environment played in the health of the people at El Palmar and what specific social circumstances contributed to the compromised health conditions of the individual in Burial 1, the presence of porotic hyperostosis sheds light on some of these matters. The condition in infancy resulted from a combination of the actions of the individual's caretakers and the cultural/environmental conditions of the social group in which this individual lived. Storey (Reference Storey1985) effectively suggests that urban centers in the Americas could have experienced problems of public sanitation and hygiene. Tropical environments provide a potential home for several endemic diseases, and parasitic infection is frequently increased by higher population density. Danforth (Reference Danforth, Whittington and Reed1997) suggests that Late Classic Maya sites could have regularly faced sanitary problems and inadequate diets, conditions that probably existed at times at El Palmar.

At a broader level, the political environment around El Palmar was unstable during the Classic period. Epigraphic evidence indicates that the nearby powerful dynasties of Tikal and Snake/Calakmul shared intense and long-term rivalries during the period between about AD 378 and 736 (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008), creating unstable social circumstances in the region. The instability in the region likely affected the health of the individual found in Burial 1, starting in early infancy and continuing throughout his life.

During infancy, caregivers modified the skull of the Burial 1 individual and permanently influenced how he looked in life. There is no evidence to indicate that cephalic modifications were a marker of social position (Tiesler Reference Tiesler1999, Reference Tiesler2014), with the exception of superior head flattening—a type of modification achieved by either using cradleboards or cephalic devices—which is commonly found in association with opulent funeral attire linked to the elites (Tiesler Reference Tiesler2014). Tiesler and Zabala (Reference Tiesler, Zabala, Murphy and Klaus2017:282) mention that “head shaping is generation-bridging to signalize enduring social identities, physical embodiment, and long-standing ideas on the body and child-rearing” (see also Duncan and Hofling Reference Duncan and Hofling2011; Tiesler Reference Tiesler2014). They also suggest that head shape would have acted as a visible sign of outer and inner beauty (Tiesler and Zabala Reference Tiesler, Zabala, Murphy and Klaus2017). Although the cultural meaning of cranial modification was probably polysemic, based on the modest funeral attire and the specific head shaping of the individual in Burial 1, the cranial modification likely emphasized a combination of the individual caregivers’ group identity(ies) and their ideas about beauty and the body, child-rearing, and ideology and was not related to sociopolitical status.

At some point during puberty or as a young adult, the individual acquired jade and pyrite inlays in his teeth that resulted in lifelong social and health consequences. Dental inlays are commonly found among individuals buried at centers associated with ruling elites (Eppich Reference Eppich2007, Reference Eppich2017; Romero Molina Reference Romero Molina and Stewart1970; Tiesler et al. Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Ramírez-Salomon, Burnett and Irish2017; Williams and White Reference Williams and White2006). For example, excavations at the el Perú-Waka’ site revealed the presence of powerful nobles (Eppich Reference Eppich2007, Reference Eppich2017). One of the el Perú-Waka’ individuals shows similar dental inlays to the individual at El Palmar. Dental inlays were also found on an individual of elevated status from Chan Chich (Geller Reference Geller, Gowland and Knüsel2006). At the site of Dos Hombres, a stone-lined tomb dating from the Early Classic (ca. AD 250–550) contained two socially prominent individuals who had type Romero E1 hematite inlays in their maxillary teeth (Geller Reference Geller, Gowland and Knüsel2006, Reference Geller and Wrobel2014), similar to the individual from El Palmar.

The dental inlays took three to four steps to complete and required a skilled craftsperson with time and access to rare materials (Fastlicht Reference Fastlicht1971; Fastlicht and Romero Molina Reference Fastlicht and Molina1951; Mata Amado Reference Mata Amado1993; Ramírez et al. Reference Ramírez Salomón, Tiesler, Arias and Amado2003; Tiesler Reference Tiesler2000). Researchers argue that dental inlays in Classic Maya society were a sign of higher social status, preferentially performed among elites who lived in the urban core of the Maya Lowlands (Geller Reference Geller2004; Sharer Reference Sharer1978; Tiesler Reference Tiesler2014; Tiesler et al. Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Ramírez-Salomon, Burnett and Irish2017). Dental procedures probably occurred during or after puberty, as inlays are infrequently found in subadults (Braswell and Pitcavage Reference Braswell and Pitcavage2009; Mayer Reference Mayer1983; Plumer Reference Plumer2017; Romero Molina Reference Romero Molina1958). Teeth alterations were probably part of a rite of initiation that occurred when a person received some charge or office that in many cases was related to religion and ideology (López-Olivares Reference López-Olivares, Whittington and Reed1997). Joyce (Reference Joyce, Nelson and Rosen–Ayalon2002) and Geller (Reference Geller, Gowland and Knüsel2006) suggest that in Maya society individuals embodied their different identities through clothing and body modification.

Dental modification likely involved pain if the drilling exposed the dentine (Geller Reference Geller, Gowland and Knüsel2006). The dentine contains many microscopic tubules with fluids; depending on the size and number of these tubules, pain and tooth sensitivity can be triggered (van Loveren Reference van Loveren2013). Geller (Reference Geller, Gowland and Knüsel2006) argues that this modification facilitated an identity change through an initiation ritual associated with becoming part of a group that shared the same experience. People in other societies also modified their teeth as a part of rites of passage into adulthood (Artaria Reference Artaria, Burnett and Irish2017; de Groote and Humphrey Reference de Groote, Humphrey, Burnett and Irish2017). Dental modifications were probably regulated by group membership and served as adornments to increase individual beauty and impart social distinction (Tiesler et al. Reference Tiesler, Cucina, Ramírez-Salomon, Burnett and Irish2017).

The individual in our sample was subjected to the dental procedure at least six times, suggesting his frequent endurance of short-term pain. These dental procedures were related to significant social events and changes in his life history. Perhaps they marked his inclusion and full participation into a more select group such as the lakam elites in the El Palmar dynasty or welcomed him to the broader social group as an adult. These physical changes are a clear manifestation of the fluidity in an individual's social identity throughout his life. The dental modifications were highly visible in face-to-face interactions when the individual spoke and opened his mouth, signaling to others his different status and identity. In addition, the raw material from one of the inlays, jade, is commonly associated with elites and was highly controlled (Taube Reference Taube2005).

Small round inlays were applied to the teeth of the individual, but only two still hold the stone pieces. The rest of the pieces were lost either antemortem or postmortem. The dental inlays probably had long-term health consequences, which may not have been noticed in life by the individual. The first right maxillary incisor has hypercementosis, an idiopathic condition characterized by abnormal growth of the cementum at the root of the tooth (Aufderheide and Rodríguez-Martin Reference Aufderheide and Rodríguez-Martin1998; Bürklein et al. Reference Bürklein, Jansen and Schäfer2012; Ortner Reference Ortner2003). This incisor had been partially drilled with a small round piece of stone placed inside the hole.

Long before the individual died, this person experienced extensive antemortem tooth loss on the left side of the mandible, indicated by the presence of extensive alveolar reabsorption in this area. None of these dental issues seem to be related to the inlays. Antemortem tooth loss probably affected some aspects of his life, creating challenges to chewing hard food with the left side of the mouth. There was also a possible abscess on the first mandibular lower right premolar that likely caused pain, in addition to a moderate accumulation of dental calculus, a hardened form of plaque.

The man in Burial 1 experienced other health problems throughout his life, including a fractured right tibia from which he had recovered years before death. We cannot determine whether this was a result of an accident or a violent encounter, but we do know that this kind of fracture is often seen today in contact sports such as rugby, football, and soccer (Emami et al. Reference Emami, Bengt Mjöberg and Larsson1996; Praemer et al. Reference Praemer, Furner and Rice1992; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Finkemeier and Tornetta2003). The iconographic representation of ballplayers on the Guzmán stairway suggests that members of the lakam participated in or witnessed ballgames, but no additional evidence connects this injury specifically to ballgame activities. Ballgames were common and visible public events among the Classic Maya with a risk of injury, entangling sacrifices and power (e.g., Cohodas Reference Cohodas, Scarborough and Wilcox1991; Stoll and Anderson Reference Stoll, Anderson and Voorhies2017).

He also had healed periostitis on the radii. Periostitis, which results in some tenderness and aching pain in the afflicted area (Aufderheide and Rodríguez-Martin Reference Aufderheide and Rodríguez-Martin1998; Ortner Reference Ortner2003), is commonly caused by nonspecific bacterial infection, trauma, tuberculosis, or metabolic disorders like scurvy and rickets (Novak et al. Reference Novak, Howcroft and Pinhasi2017; Ortner Reference Ortner2003; Weston Reference Weston and Grauer2012). No evidence of tuberculosis or rickets was observed elsewhere. As he aged, light to moderate degenerative joint disease (DJD) developed in the articulations of the right elbow, hands, left knee, left ankle, and feet (Aufdeheide and Rodríguez-Martin Reference Aufderheide and Rodríguez-Martin1998; Ortner Reference Ortner2003). DJD has been observed in Maya areas, especially in individuals of higher socioeconomic status associated with crafting and specialized labor (Plumer Reference Plumer2017). Individuals with DJD experience pain and stiffness around the affected areas, particularly after periods of inactivity or in the mornings, and the pain often increases in intensity with age (e.g., Sharma Reference Sharma2016; Wesseling et al. Reference Wesseling, Bierma-Zeinstra, Kloppenburg, Meijer and Bijlsma2015).

DJD has a multifactorial etiology and can be associated with obesity, repeated mechanical stress to a joint, and age (Rogers and Waldron Reference Rogers and Waldron1995; Weiss and Jurmain Reference Weiss and Jurmain2007). The DJD observed in his hand and elbow joints could be evidence of different activities and manual labor, possibly a result of the tasks performed by standard-bearers with their hands. His role as a banner-bearer in life was embodied in his body. Creating and carrying a shaft or pole representing the rulers of El Palmar for a long time and distance can undoubtedly create physiological stress in the joints. The DJD in the knees and ankles could be related to normal weight-bearing and aging (Zampetti et al. Reference Zampetti, Valentina Mariotti and Belcastro2016), as well as activities that placed significantly more force on the knee by requiring frequent bending from ascending and descending stairs, crossing varied terrain, and hiking (Austin Reference Austin2017; Jensen Reference Jensen2008; Komistek et al. Reference Komistek, Kane, Mahfouz, Ochoa and Dennis2005). If he was an ambassador or banner-bearer and therefore involved in a tributary role as part of the standard-bearers, it is likely that he frequently went up and down stairs and often walked shorter and longer distances over a wide range of terrains. The Central Karstic Upland in which El Palmar is located contains undulating landscapes that probably placed a burden on his body. Rice (Reference Rice2007) mentions that expeditions can also involve trading, pilgrimages, and chiefly legitimation rituals, among other activities, and were clearly part of elite culture, power, legitimation, and wealth.

Braswell (Reference Braswell, Smith and Berdan2003:302) stresses the political importance of Maya ambassadors who were engaged in long-distance travel to discuss political and trade issues. He mentions that Hernán Cortés's fourth letter to the Crown describes a meeting with a delegation from Kaqchikel in northern Veracruz seeking an alliance with the Spaniards against the K'iche’. Additionally, a possible lolmay or lolmet, the K'iche name for ambassador, visited the Aztecs in Xoconochco for political reasons (Braswell Reference Braswell, Smith and Berdan2003:302). These historical narratives accord well with the inscriptions of the Guzmán stairway at El Palmar, which commemorate the journey of Ajpach’ Waal as an ambassador to Copán under the auspice of Calakmul's Snake Dynasty.

The osteobiography of the individual suggests that his status changed during his life. Close to his death around AD 726, when the Snake Dynasty attempted to ally with Copán through El Palmar, the economic and sociopolitical conditions of the individual interred in Burial 1 seem to have changed. He lost a dental inlay that was not replaced. We were able to identify that the decorative piece in the right maxillary canine was lost antemortem, because the circular orifice of enamel contains a moderate amount of calculus (Figure 6). Replacing a decorative piece was probably important for maintaining the status of the person in face-to-face interactions; thus, it is possible that this antemortem loss signified a change in his status before death. The modest offering of only two polychrome vessels could indicate moderate wealth for Individual 1, given that high-status burials usually contain more elaborate offerings in Classic Maya society (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1992; Coe Reference Coe, Benson and Griffin1988; Haviland and Moholy-Nagy Reference Haviland, Moholy-Nagy, Chase and Chase1992; Tiesler and Cucina Reference Tiesler and Cucina2006; Weiss-Krejci Reference Weiss-Krejci, Fitzsimmons and Shimada2011). There are some exceptions, of course, as in the case of Piedras Negras (see Plumer Reference Plumer2017; Scherer Reference Scherer2015) and Río Bec, an archaeological site close to El Palmar where grave construction does not correlate with social hierarchy (Pereira Reference Pereira2013).

Burials in the Maya area are usually found within household structures (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1996; Plumer Reference Plumer2017). The individuals buried within the structures were most likely the owner of the residence, important household members, or other distinguished relatives (McAnany Reference McAnany1995, Reference McAnany and Houston1998; Weiss-Krejci Reference Weiss-Krejci, Fitzsimmons and Shimada2011). The placement of the individual in Temple GZ1 attests to his sociopolitical importance among lakam elites. The mourners carefully placed the body of the individual, along with polychrome vessels, in a cist that had been cut into the plaster floor of Structure GZ1. His placement under the floor in close connection to the living provides a direct link to and constant reminder of this individual, his lineage, and collective group histories. The burial was closed with slabs, and a fire ritual was performed on top of the cist. Cists and slabs placed in cists have been found at other Maya sites (Brady and Ashmore Reference Brady, Ashmore, Ashmore and Bernard Knapp1999; Pereira Reference Pereira2013) and are symbolically associated with caves and ideas about the underworld (Brady and Ashmore Reference Brady, Ashmore, Ashmore and Bernard Knapp1999; Pereira Reference Pereira2013). Traces of fire observed at the point of closure could link the dead with the house and honor the deceased (Fitzsimmons Reference Fitzsimmons2009; Pereira Reference Pereira2013). Thus, the fire ritual found in Burial 1 was tied to both the internment and the building ceremony of the hieroglyphic stairway.

At the Guzmán Group, both archaeological evidence of the fire ritual and its iconographic representation on the offering vessel reinforce the sociopolitical importance of this person, probably embodying his various identities. The timing of the burial in conjunction with Ajpach’ Waal's claim of the eastern temple in the texts suggests that the individual is either Ajpach’ Waal himself or his father, Ajlu…Chih. There is no textual evidence from the burial offerings indicating the name and title of the person. Nonetheless, Ajpach’ Waal is a strong candidate judging from his emphasis on his ownership of the temple and the entire group.

Conclusions

In this article, inspired by the life course and osteobiographical approaches, we explore who the individual found in Structure GZ1 was and what kind of experiences he had throughout life and death. Different lines of evidence suggest that the individual in Burial 1 experienced diverse social, political, and economic situations that constantly changed during his life and at his death. Living through periods of political turbulence, he must have experienced a wide array of events that shaped and reshaped his identities, affiliations, and sociopolitical status throughout his life course.

We consider the importance of fluidity in individual identities. These multiple intersecting identities are often challenging to extract from artifactual analyses, epigraphic studies, or osteological analysis alone. Combining diverse methods, however, sheds light on the formation and transformation of the variable identities of an individual. Our approach revealed a nonroyal elite member of Classic Maya society who was linked both to local internal politics and regional dynastic interactions. This person suffered a variety of diseases, injuries, and pain throughout his life. His kin were also likely concerned with beautification even when they were physically uncomfortable and underwent painful procedures such as cranial modification and dental inlays. Individual 1 probably frequently witnessed and was actively engaged in critical political events as a standard-bearer for El Palmar's royal elites. At the end of his life, he was buried and commemorated by members of his group in a unique carved monument that is regularly associated with royal elites in the Maya lowlands. Future studies of human remains from El Palmar will help incorporate this individual into more nuanced contexts regarding health, trauma, and physical appearance in this dynasty.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the Consejo de Arqueología INAH; Centro INAH Campeche; Coordinación Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural; Ejido Kiché Las Pailas, the codirector of the El Palmar Archaeological Project, Javier López Camacho; and the project crews for their support. Special thanks to Thomas Fenn, Matthew Pailes, Marc Levine, Marijke Stoll, Jessica Munson, and reviewers for their productive comments and suggestions for an early version of this article. This research was supported by awards to Tsukamoto from the National Science Foundation (BSC-111640) and the JSPS KAKENHI (15J00280, 19K13408, and 20H05141).

Data Availability Statement

All osteological inventories and field notes for this study are stored in the Bioarchaeology Laboratory, Department of Anthropology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, and the Department of Anthropology University of California, Riverside. All data are available upon request from the authors.

Supplemental Materials

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.96.

Supplemental Text 1. Osteological Analysis.