Introduction

Only recently there have been attempts to bridge the literatures between the welfare state and party politics focussed on the populist radical right. One of these difficulties has been the heterogenous nature of the ideologies and policy agendas of these parties. However, after the Great Recession, there is now a general agreement of the ideologies of Populist Radical Right Parties (PRRP) as combining nativism, authoritarianism, and populism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2015),Footnote 1 and their ‘policy platforms seem[ing] to have become more consistent over time’(Rathgeb and Busemeyer, Reference Rathgeb and Busemeyer2022: 15): ‘not so blurry after all’ (Enggist and Pinggera, Reference Enggist and Pinggera2022), embodying ‘welfare chauvinism’, ‘welfare nostalgia’, ‘producerism’, and ‘particularistic-authoritarianism’ (Fenger, Reference Fenger2018; Ivaldi and Mazzoleni, Reference Ivaldi and Mazzoleni2019; Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Rathgeb and Sahm2022; Rathgeb and Busemeyer, Reference Rathgeb and Busemeyer2022). This now allows for research on PRRP voting to move beyond socio-cultural explanations (i.e., immigration, crime, national way-of-life) and ask ‘how might the welfare state [and economic policies] shape the fortunes of RPPR’ (Rathgeb and Busemeyer, Reference Rathgeb and Busemeyer2022: 2)?

While early radical right parties attracted petite bourgeoise interested in economic deregulation and socially conservative working-class voters, increasingly studies have tied motivations for PRRP voting into a framework based on the threat of social status decline (Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Engler and Weisstanner, Reference Engler and Weisstanner2021) related one’s employment (Im et al., Reference Im, Mayer and Palier2019). If occupational risk is a potential factor in determining propensity to vote for populists, then arguably, governments can institute policies that mitigate such risks, such as providing compensatory social policy should one become unemployed, labour market policies that support the unemployed in finding work, or make it more difficult to fire an employee from their job. This paper joins others in assessing the contextual role that government policy has in mitigating occupational risks associated with voting for populist radical right parties – PRRP (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019; Im et al., Reference Im, Mayer and Palier2019; Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022).

While the focus of the above research has been on those facing social status decline, too often overlooked are the political behaviours of those experiencing socio-economic status increases in the contemporary economy (Gallego and Kurer, Reference Gallego and Kurer2022). Subsuming all workers in occupations subject to automation into a single measure produces some inexplicable findings, such as that these workers are more likely to vote for the populist radical right with greater amounts of public service provision (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019: 5, 7). Below, the preferences of the ‘modernization winners’ – managers and professionals – are argued to diverge from the preferences of those facing decline and are then analyzed as such.

Finally, the implementation of such policies that intend to ‘cushion’ radical right support, might have an adverse feedback effect of ‘catalyzing’ greater support for radical right parties (Ennser-Jedenastik and Koeppl-Turyna, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Koeppl-Turyna2018). Should policies favour socio-demographic groups that potential populist radical right voters displease of, such as those not affiliated with nostalgic views of the welfare state like immigrants or labour market outsiders or those not involved in ‘producerist’ activities, like the unemployed, voters might turn to the populist radical right to reorient policies in favour of those currently employed, especially if such policies are large enough to be quite ‘visible’ to labour market observers, and thus potentially raise the salience of such programmes (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2014; Rathgeb and Busemeyer, Reference Rathgeb and Busemeyer2022).

This paper blends these three lines of research: occupational labour market risks, preferences over labour market policies, and heterogeneous feedback effects of such policies. Taking inspiration from similar studies on the topic, this article explores to what extent employment risk can predict voting for populist parties and if public policy can mitigate or exacerbate these risks (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019; Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022). However, this article differs from others in the use of multiple measures of labour market insecurity, the focus on government labour policy, and modelling heterogeneous effects based on labour market hierarchies. Using three rounds of post-Great Recession European Social Survey (ESS, 2018; ESS, 2020; ESS, 2021) data collected between 2014 and 2018 from 14 countries, results indicate that (1) voters’ objective economic position relates to their subjective risk assessment; (2) PRRP differ on their labour policy preferences as compared to other voters; (3) government labour policy has an impact on voting decisions; (4) these policies have heterogeneous effects across employed individuals; and (5) larger government interventions may produce a positive feedback on populist voting. Strong employment protection or spending on active labour market policies may catalyze highly specialized workers and routine workers in elementary occupations to become even more predisposed towards voting for the radical right. If governing mainstream parties wish to limit the popularity of populist parties, greater spending and interventions may work at odds towards these goals depending on the nation’s occupational structure.

Occupational risk and the demand-driven populism in the 21st century

Demand-side explanations of populism have focussed on how globalization, neoliberalism, and technological change have made life more insecure for the working and middle classes, while enhancing the status of those with higher education and higher skills (Berman, Reference Berman2021). The diffusion of computers complemented skilled workers, increased their salaries, and led to job growth in high-tech high-skill fields (e.g., engineering and management) and low-paying service jobs that cater to them; however, this same process substituted for labour in routine tasks performed in industrial, sales, or clerical middle-income occupations accessible to those without college degrees (Gallego and Kurer, Reference Gallego and Kurer2022). In the 1990s and 2000s, routine occupations decreased by a relative third while nonroutine analytical and interactive occupations have increased by a third (Oesch, Reference Oesch2013). This has led to a decrease in the share of routine occupations in the middle of educational and wage distributions, polarizing the workforce (Autor et al., Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2015) into ‘modernization winners’ and ‘modernization losers’ (Halikiopoulou and Vlandas, Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2016). Populist parties benefit from the lack of responsiveness of mainstream parties to changing socio-structural transformations of society (Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos, Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020). The Manichean, us-versus-them, worldview of populists pits the ‘us’ of those being made more insecure against the ‘them’ of perceived beneficiaries of change: liberal elites, government bureaucracy, minorities, and new social groups competing for jobs, including immigrants, foreign workers, fixed-term or part-time employees, and women.

The underlying risk of occupational unemployment can thus be thought of as a continuum (Marx and Picot, Reference Marx and Picot2020) that varies by skill level (Iversen and Soskice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2001), skill specificity (Cusack et al., Reference Cusack, Iversen and Rehm2006), and the tasks performed at work (Kaihovaara and Im, Reference Kaihovaara and Im2020). Those with high incomes in the current economy or education that enables them to find gainful employment in the current economy face the least risks, such as those in managerial positions or self-employed professionals (Rehm, Reference Rehm2009).

Workers in professions requiring specific skills are likely to face greater labour market risks. A petroleum engineer in a petrochemical surveying firm might have skills that would be useless in other professions. As such, she would face more risks than an office manager, whose inter-personal and administrative skills might transfer well to other occupations. Thus, the former would prefer more government intervention to protect her job. Individuals with specific skills have been found to be more supportive of redistribution, for if they lose their occupation, they will be less likely to be able to find equally gainful employment (Iversen and Soskice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2001). Given their low level of re-employment potential (Cusack et al., Reference Cusack, Iversen and Rehm2006), policies that ensure the stability of employment would likely reduce their perceived risk of income loss. Relatedly, they also prefer greater spending on unemployment, industrial aid, and healthcare (Gingrich and Ansell, Reference Gingrich and Ansell2012).

The prospect of automation also lies on a spectrum related to the tasks associated with particular occupations. Some tasks follow a script or set of rule-based procedures. Computers can perform routine, defined, and repetitive tasks like manufacturing, data transcription, or record keeping, though are {yet} unlikely to replace abstract interpersonal tasks or service skills like truck driving or food preparation. These tasks are not necessarily related to education or training, for even complex tasks can be routinized (e.g., bookkeeping) (Thewissen and Rueda, Reference Thewissen and Rueda2019). Even if they are institutionally well protected, workers with highly routine (i.e., automatable) tasks might perceive economic insecurity (Marx and Picot, Reference Marx and Picot2020) and thus support programmes that would aid them, were they to suffer from a reduced income, as a form of insurance against occupational hazards. Indeed, support for redistributive programmes increases with job routinization, moreso among high-income groups who have more to lose, and of a greater effect than those with high levels of skill specificity (Thewissen and Rueda, Reference Thewissen and Rueda2019).

A consistent finding of the literature is that those who lose out to technological innovation – those in routine occupations (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019) or at risk of automation and coping financially (Im et al., Reference Im, Mayer and Palier2019) – turn against the political status quo and towards PRRP (Gallego and Kurer, Reference Gallego and Kurer2022). With increasing income inequality, the loss of jobs to outsourcing and skill-biased technological change would likely produce a fear of falling further down the income and social ladder, creating a sense of status anxiety and feeling ‘left behind’: a feeling strongly felt by those with lower levels of education and those working in low-skill services or routine occupations like mail sorting clerks and shop assistants (Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2020). Whether valid or not, individuals worried about their worsening financial situation due to automation or foreign or domestic competition become resentful and susceptible to the anti-establishment messages put forth by populist parties (Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Berman, Reference Berman2021; Gallego and Kurer, Reference Gallego and Kurer2022).

Economic and social policy preferences of PRRP and voters

While less than a decade ago, research had concluded that populist right parties tend to blur their economic positions (Rovny, Reference Rovny2013), by the mid−2010s their policy agenda had become more distinct and responsive to their core working-class constituency. Echoing the notion of economic decline, Fenger’s ‘welfare nostalgia’ perspective (2018) holds that social benefits should be reserved for traditional workers (‘modernization losers’) based on traditional economic and family patterns at the expense of migrants, women, the self-employed, and temporary workers. In Fenger’s analysis of speeches and manifestos post−2010 from six nations, PRRPs tend to reject ‘the necessity to adjust the welfare state to new economic, demographic, and social realities like an ageing population or growing single parenthood’ (Fenger, Reference Fenger2018: 202).

This stands in contrast to the ‘social investment paradigm’ of flexible labour markets and a commitment to lifelong education to prepare individuals, families, and societies for new risks as opposed to protecting against the old through measures such as early retirement or unemployment assistance. Protecting the losers of modernization would imply a return to the golden age of the welfare state and undoing many social investment reforms (Fenger, Reference Fenger2018). An analysis of manifestos, from mainly 2017 and later, have identified that PRRP take the strongest stances against social investment measures – childcare, higher education, rehabilitation, retraining, job-search search assistance – and the strongest stances favouring old age pensionsFootnote 2 (Enggist and Pinggera, Reference Enggist and Pinggera2022).

‘Producerist’ frames have also come to be representative of PRRP economic approaches. Producerism argues that ‘the producers’ of the nation’s wealth should be able to enjoy the economic fruits of their labour, privileging individuals and groups driven by work (Ivaldi and Mazzoleni, Reference Ivaldi and Mazzoleni2019). Just as populism is characterized by a morality of a good people and corrupt elite, producerism suggests that workers are virtuous, being squeezed by non-productive ‘parasites’ above – bureaucrats, politicians, elites, bankers, and international capital – and below – immigrants, undeserving poor using benefits – who live off their labour. Again, the focus here is on the economic decline and threatened position of the ‘true’ people characterized by their ‘work ethic’ – the workers; ‘the makers’ against the ‘the takers’, and a nostalgia for an idealized past of real community values with traditional hierarchies of social prestige (Ivaldi and Mazzoleni, Reference Ivaldi and Mazzoleni2019; Rathgeb, Reference Rathgeb2021). Again using data from after the Great Recession (Ivaldi and Mazzoleni, Reference Ivaldi and Mazzoleni2019), producerist frames can be found in publications associated with the Tea Party Movement, ‘Prosperity and opportunity come from the ingenuity and hard work of individuals and entrepreneurs, not from government’ (ibid 14), France’s National Front opposing job market flexibility and Le Pen campaigning, ‘more and more people are getting social benefits, but it is always the same people who get welfare, and the same people who have to pay for it’ (ibid 19), Swiss People’s Party’s claim that the ‘welfare of the middle-class are undermined because of the growth of social expenditure’ (ibid 20), the Dutch Party for Freedom and Flemish Interest stressing the need to counter fraud and abuse by those unwilling to work to protect hard earned social security, and all PRRP parties expressing scepticism about the ability of the state to manage welfare arrangements in terms of cost-effectiveness and directing towards the deserving recipients, with the Dutch Party for Freedom noting how ‘millions of people sit at home on benefits’ (Abts et al., Reference Abts, Dalle Mulle and van Kessel2021: 29, 30, 33).

Combined, these economic policies exhibit a ‘nostalgic producerism’. Focussing on ‘hard-working’ typically male breadwinners is not simply rhetoric, as emerging studies have also identified what policies result from PRRP in government. Their aversion towards bureaucratic complexity (Meardi and Guardiancich, Reference Meardi and Guardiancich2021) has led them towards retrenching programmes that benefit public servants (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Afonso and Spies2018). They have expanded familialist policies defending a male-breadwinner model that promotes ‘work, family, fatherland’ (Meardi and Guardiancich, Reference Meardi and Guardiancich2021) and have prevented right-wing coalition partners from further retrenchment or deregulation, even producing increases in welfare state generosity and economic regulation in governments that last longer than 1 year (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Afonso and Spies2018). In a case study examining Austria’s Freedom Party in office, Rathgeb looks for evidence of this PRRP targeting the entitlements of employees with short and discontinuous employment while defending the rights of workers with long employment records and ‘male breadwinners’ through tax breaks and benefits for families. While in government, the Freedom Party created an early retirement scheme for those with 40/45 (f/m) years of paid employment and a new child benefit scheme, consenting to cuts to non-standard workers with a discontinuous employment history, and opposed plans to reduce the maximum duration of unemployment benefits for workers with long contribution records (Rathgeb, Reference Rathgeb2021).

Relating back to the key aspects of Mudde’s (Reference Mudde2015) characteristics of RPPR ideology, a RPPR economic ideology composed of ‘Economic Nativism’, ‘Economic Authoritarianism’, and ‘Economic Populism’ can also be found in several party manifestos independent from traditional left-right issues (Otjes et al., Reference Otjes, Ivaldi and Jupskås2018). RPPR parties thus, respectively, advocate for (1) privileging nationals’ access to healthcare, welfare benefits, and crucial economic sector ownership; (2) excluding the underserving poor {criminals, fraudsters, unemployed refusing to work}, who threaten the sustainability of the welfare state for the working and deserving poor; and (3) reducing the number of civil servants and expenditure on politicians: “the corrupt elite” ignoring or betraying the well-being of the “people” (Ivaldi and Mazzoleni, Reference Ivaldi and Mazzoleni2019).

The supply side of economic policy of PRRP is congruent with their voters, also surveyed in the mid−2010s – as not easily being transcribed onto a left-right dimension. PRRP voters are found to hold sceptical views of the behaviours of welfare recipients (Attewell, Reference Attewell2021). Busemeyer et al. (Reference Busemeyer, Rathgeb and Sahm2022) identify a particularistic-authoritarian model of the welfare state held by PRRP voters that echoes the nationalist, particularistic, and exclusionist solidarity of producerism advocated by PRRP that divides society into the deserving and undeserving that should be punished. PRRP voters are found to oppose social investment and have limited support of social transfers: low levels of support for increasing expenditure for education, family support, assistance to the poor, unemployment benefits, and labour market programmes; more than a majority of PRRP supporters supported an expansion of pensions and healthcare; and PRRP supporters were found to be particularly fond of ‘workfare’ policies that require those on unemployment to accept employment quickly.

Does labour market policy cushion PRRP support?

Having thus now identified a set of issues driving demand-side populism – status anxiety and labour market risk – and the types of policies advocated for by PRRP, the two literatures can help determine an individual’s policy and political preferences. In short, the risks a family-wage earner faces in the labour market determine one’s preferences for social and labour policy (Iversen and Cusack, Reference Iversen and Cusack2000), and theoretically, the welfare state can mitigate occupational risks and moderate the impact of economic insecurity and therefore support for PRRP (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019; Rathgeb and Busemeyer, Reference Rathgeb and Busemeyer2022; Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022). At the macro-level, governments that have more generous welfare regimes, and had smaller retrenchment experiences, tend to have less support for populists (Foster and Frieden, Reference Foster and Frieden2019). The argument that follows explores the effect of labour market policies at the micro-level. While the idea that groups might experience different levels of insecurity across nations is not controversial, it is still rarely explored in the literature (Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022: 7): at its core, the question remains unanswered of whether government policies that mitigate economic distress actually ‘work’ in preventing economic insecurity from being translated as political insecurity.

Two studies speak directly to this micro-level question. In previous research, Halikiopoulou and Vlandas (Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2016) identified the role that labour policies can have on depressing support for national levels of PRRP support in European Parliament elections. The ‘costs’ of unemployment are reduced with greater unemployment benefit spending serving as a form of compensation while dismissal protections reduce the ‘risk’ of unemployment in the first place. When these are high, national unemployment levels do not lead to increased support for PRRP. They expand upon and apply this theory at the individual-level identifying several forms of compensatory policy – unemployment benefits for the unemployed, pension benefits for retired, disability policies for the disabled, childcare policies for parents – and regulatory policy – Employment Protection Legislation (EPL) for permanent contract workers and minimum wages for low-income workers – that might reduce the levels of individual insecurity and thus moderate the support for PRRP (Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022). No distinction is made, however, between individuals facing different occupational risks associated with the winners and losers of modernization, although this call is made in their conclusion.

Gingrich (Reference Gingrich2019) specifically investigates this distinction by focussing on the impact that ‘policy responses to automation’ has on routine versus non-routine workers. The investigated policies include compensatory early retirement, government in-kind service spending aiming to capture the integration and employment of new cohorts of workers, and EPL protecting the traditional workforce. The results as it relates to voting for PRRP are limited. While indeed more routine workers are more likely to vote PRRP, none of these policies is shown to mitigate the relationship. In fact, greater in-kind service spending was found to increase the likelihood of voting for PRRP among those with higher levels of job routinization.

There are two potential misspecifications that can provide guidance on why EPL cushions PRRP voting for average voters but not those in routinized positions. The first is the grouping of all routine workers under a single measure of job routineness. While the focus of much research has been on the losers of modernization/digitalization, there has been less of a focus on the political behaviour of modernization/digitalization winners (Gallego and Kurer, Reference Gallego and Kurer2022). While middle- and lower-skill routine labour has lost out, the professionals at digitizing firms certainly benefit from the increased productivity and though perhaps engaged in routine occupations would not be concerned about compensatory social or labour programmes. Highly skilled workers in routinized industries might in fact benefit from automation (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019), as computerization of simple tasks could result in jobs of greater complexity (Autor et al., Reference Autor, Levy and Murnane2002). Differentiating between low-skilled routine workers as compared to higher skilled could produce alternative results, resulting in their average producing insignificant effects.

A second misspecification similarly lies in the interaction between routineness and employment protection. As noted above, some routine positions might gain from digitization and workers might be interested in easily transitioning into newer productive firms. As opposed to occupational routineness, a worker might be more concerned about their skill specificity. The more specific a worker’s skill is to a job or firm, the more sensitive to adverse economic conditions an individual would be, as they may have to accept re-employment in jobs where their skills (and the returns to investment in such skills) cannot be transferred (Cusack et al., Reference Cusack, Iversen and Rehm2006) resulting in lower incomes. As such, workers with more specific skills are more concerned about the possibility of income loss and more likely to support government intervention (Iversen and Cusack, Reference Iversen and Cusack2000).

Beyond misspecification, the “nostalgic producerist” economic policy stances of PRRP discussed above also provide a more thorough explanation for why government service spending might catalyze PRRP voting. PRRP favour some types of labour market intervention at the expense of others:

-

(a) Employment protection legislation would serve as a preferred form of labour market intervention as it captures the producerist aspect of PRRP economic policy. These policies directly benefit ‘the makers’ by making it more costly to fire workers and enables workers and collective organizations to challenge dismissal. With greater dismissal costs, firm management – ‘the takers’ – would be less likely to resort to firing workers during economic downturns (Halikiopoulou and Vlandas, Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2016), in effect preventing risks from arising in the first place (Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022).

-

(b) Active labour market spending – employing government bureaucrats to aid in the training, job search, and integration of new social groups like the long-term unemployed and labour market outsiders such as those on non-traditional contracts – would serve as the least preferred form of labour market intervention. These policies engage with the social investment perspective, specifically benefitting non-traditional workers and ‘labour market outsiders’ (Swank, Reference Swank, Careja, Emmenegger and Giger2020) while employing complex public bureaucracies. This form of intervention stands in strong contrast to the nostalgic forms of welfare state activities, protecting the male-breadwinner. Ennser-Jedenastik and Koeppl-Turyna (Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Koeppl-Turyna2018) would also argue that generous government services make voters more concerned about increased numbers of immigrants coming in to claim benefits, as larger programmes are more visible on the minds of voters and raise the salience of such issues (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2014).

-

(c) Unemployment assistance serves as a middle ground. While indeed workers at risk would hope there would be generous unemployment benefits, should they need it to cushion the decline in economic status associated with unemployment, requiring unemployment would thus transform someone into a ‘taker’. The workfare attitudes expressed by PRRP voters and statements from PRRP highlight the abuses of the undeserving beneficiaries of such programmes (Abts et al., Reference Abts, Dalle Mulle and van Kessel2021) who should be held to tight restrictions and the inefficiencies of government bureaucrats administering them. Unemployment compensation might not be enough to cushion potential PRRP voters, as they are not especially strong supporters of redistributive programmes to begin with (Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2020).

Can labour market policies catalyze support for PRRP?

Social and labour market institutions produce ‘policy feedback’ (Gingrich and Ansell, Reference Gingrich and Ansell2012; Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2014), as existing structures tie more citizens hands to them and create a self-reinforcing preference for stronger government intervention (Pierson, Reference Pierson1996). Cutting these programmes in favour of new ones faces opposition by beneficiaries and the clientele of pensions, unemployment, and healthcare (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann, Bonoli and Natali2012).

The finding that large welfare expenditures might catalyze support for the PRRP has been noted or suggested by other works than those already discussed above (Rooduijn and Burgoon, Reference Rooduijn and Burgoon2018; Rathgeb and Busemeyer, Reference Rathgeb and Busemeyer2022). More formally, this suggests that some policies might have a “self-undermining” feedback effect, whereby high levels of intervention might lead to public opinion (and voting behaviour) to decrease interventionism and vice versa (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Abrassart and Nezi2021).

Active labour market policies employ government workers and financing in a direct role in re-education, job placement, and subsidization of wages. Such measures tend to reduce subjective economic insecurity moreso than social policy generally (Anderson and Pontusson, Reference Anderson and Pontusson2007) as they have the ‘unambiguous objective’ to benefit those facing labour market risks (Rueda, Reference Rueda2014: 388). Higher levels of spending on labour programmes have a risk-homogenizing effect, with the state bearing more of the burden of addressing economic risks and uncertainties faced by individuals (Gingrich and Ansell, Reference Gingrich and Ansell2012). Spending on active measures has been correlated with increasing levels of employment (Barbieri and Cutuli, Reference Barbieri and Cutuli2016), which might be particularly beneficial to routine service workers, who are subject to the highest levels of labour market vulnerability in post-industrial economies (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2020).

Yet, large social programmes might also prime low-skilled workers about potential competition from low-skilled immigrants entering a country and claiming benefits from the taxes and contributions of the native population (Ennser-Jedenastik and Koeppl-Turyna, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Koeppl-Turyna2018). More ‘visible’ welfare states and labour market interventions shape the overall salience of social programmes (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2014). Voters tending towards PRRP might then be strongly primed by observations of a policy they tend to disfavour. As opposed to compensating for labour market risks, greater spending on active measures might then increase PRRP vote shares (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019). As active labour market policies directly involve larger government resources to implement (or mismanage), they suggest an increase in the size of the bureaucracy (‘the takers’) and involve a social investment in a universal programme for those needing unemployment assistance (‘the undeserving’), we could suppose that the impact of active labour market policy spending might ‘self-undermine’ this programme and lead voters to PRRP, who have taken the strongest stances against this policy formula. Thus, one should expect the following:

Spending on active labour market policies catalyzes support for PRRP, with the exception of lower-skilled non-tertiary workers, whose occupations tend to have greater employment as a result of these programs (Escudero, Reference Escudero2018).

Relaxing employment protection legislation was implemented through the 1990s and early 2000s as a remedy against low economic growth, slow job creation, and broad macro-economic shocks (Barbieri and Cutuli, Reference Barbieri and Cutuli2016). Both economic liberal and social democratic parties were among the main advocates of such policies. The reduction in employment protection legislation for those nations that did engage in liberalization tended to not have the expected effect of increasing employment (Barbieri and Cutuli, Reference Barbieri and Cutuli2016). One can consider such a situation to contain ‘self-reinforcing’ feedback effects, whereby nations with a high level of intervention have interest groups supporting the continuation of such interventions, while nations with low levels of existing intervention lack an interest group environment advocating for reform.

Employment protection unambiguously benefits those with specific skills (Estevez-Abe et al., Reference Estevez-Abe, Iversen and Soskice2001). Individuals who make risky investments in specific skills will demand policies that protect against possible future loss of those investments. These along with low-skill routine workers would thus have the most to lose from liberalization. As employment protection does not require large government resources to implement, suggest an increase in the size of the public sector, or grant benefits to the unemployed or ‘undeserving’, specialized workers or low-skill routine workers in situations of high employment protection through self-reinforcing feedback effects are thus a prime constituency for a PRRP voter, who post-2010 have not indicated any support for retrenching such policies. Thus, one should expect the following:

The probability of PRRP voting is cushioned for most workers through increasing levels of EPL, though protected highly-specialized and low-skill-routine workers may be catalyzed by strong EPL, promoting a PRRP vote.

As discussed previously, the effect of unemployment benefits is ambiguous, and as such, no directional expectation is clear. That said, given the inclusion of this labour market policy by other scholars, it would be inappropriate to not analyze whether this policy, too, can cushion or catalyze support for PRRP.

Data and methods

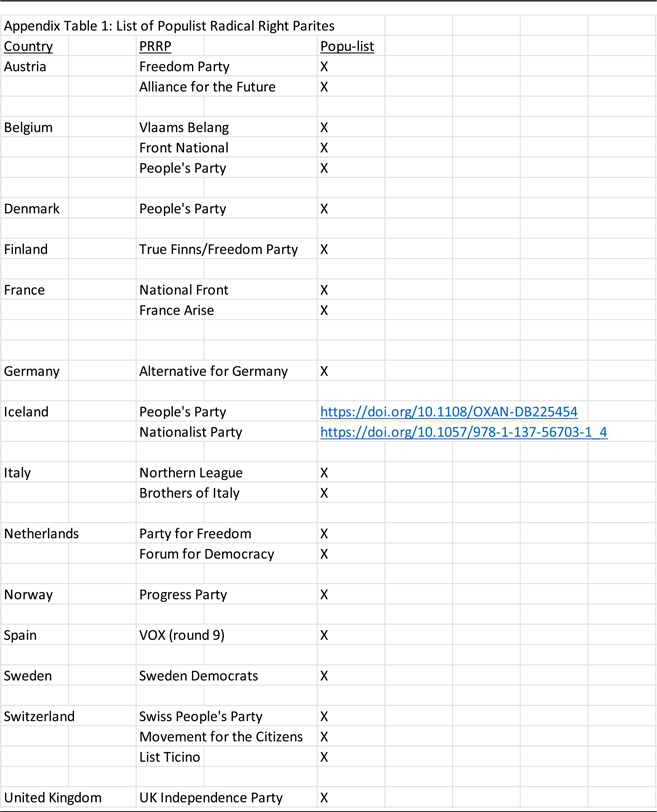

Data on preferred party were taken from the vote choice variable in European Social Survey rounds 7–9.Footnote 3 PRRP in each nation are identified following the work of previous scholars (Foster and Frieden, Reference Foster and Frieden2019; Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019; Attewell, Reference Attewell2021; Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022) with updated coding for the latest ESS rounds using the PopuList.Footnote 4 To best dialogue with other studies of voting interested in state-feedback effects towards labour market risks and populist voting, the sample is restricted to those actively in the labour market (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019) earning income from wages on permanent contracts (Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022). Also following the approaches of others who also have individual-level variables, national-level variables, and cross-level interactions, multi-level random intercept models will be used (Gingrich and Ansell, Reference Gingrich and Ansell2012; Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022). All models include errors and intercepts clustered at the country-ESS round level (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019), of which there are 37 in this analysis, weights provided by the ESS,Footnote 5 and controls for national economic conditions: GDP growth, unemployment level, and GINI inequality (OECD, 2020), as each of these has a potential impact on the job market, perceived economic condition, and PRRP vote shares.

A variety of individual characteristics typical in voting and social policy preference literature were identified (Gingrich and Ansell, Reference Gingrich and Ansell2012): 10-point decile family income, female, age, part-time, current trade union membership, children if live in household with children, public sector if one’s primary employment is for the government or government services (as these employees would be protected from international or domestic competition) (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2020), and if someone is currently a student. Educational attainment is also coded, as those with greater education have been found to be less likely to vote for populist parties as high-skilled service workers are the winners of modernization (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2020). As ideology, immigration opinions, and religiosity have been regularly used in studies of PRRP voting, a 10-point left right scale is included, as is a control for religious where respondents could rate themselves on how religious they were with 10 signifying “very religious”. A measure of those Favorable (toward) Immigration is also included.Footnote 6

ESS data uses the International Standard Classification of Occupation (ISCO), which classifies occupational groups hierarchically according to their similarity in terms of job and skill into 438 categories. For example, a level 1 measure of “clerks” is broken down into level two measures of “office clerks” and “customer service clerks”, which can be broken down into level 4 measures of 24 different occupations including secretaries, data entry operators, scribes, tellers, and travel agency clerks. Occupational characteristics are coded as follows:

Specialization is derived by Cusack et al. (Reference Cusack, Iversen and Rehm2006) to measure the ‘s1’ ‘relative skill specificity’ measure of Iversen and Soskice (Reference Iversen and Soskice2001). Coded at ISCO − 2 digit level, the logic behind this measure is that if more of the workforce is contained within an occupational category or there is a greater level of skill specialization, then there will be more codes at the ISCO - 4 digit level. For example, ISCO code 82, ‘machine operators and assemblers,’ has 36 subcategories, whereas ISCO code 52, ‘models, salespersons, and demonstrators,’ has only three subcategories. If both groups account for around 5% of the workforce, then Iversen and Soskice (Reference Iversen and Soskice2001) argue that the former group has much more specific skills than the latter (Gingrich and Ansell, Reference Gingrich and Ansell2012). These values are standardized so that this variable ranges from 3.44 for ‘stationary-plant and related operators’ to −1.01 for ‘models, salespersons and demonstrators’.

Skill Level comes directly from ISCO level 1 measures which groups occupations on an ordinal scale of 1 to 4 (Iversen and Soskice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2001; Cusack et al., Reference Cusack, Iversen and Rehm2006) defined in terms of the educational levels and categories of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). ‘Elementary occupations’ such as sales, agriculture, or construction labourers are assigned a skill level 1 (Ennser-Jedenastik and Koeppl-Turyna, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik and Koeppl-Turyna2018). ‘Professionals’ like those employed in health, science, or higher education and ‘legislators, senior officials, and mangers’ are assigned a skill level 4. ‘Technicians and Associate Professionals’ are rated a 3 and most other professions have a skill level of 2 termed as ‘Craft, Assembly, Clerk, & Service Occupations’ in this article, composed of clerks, service workers, shop and market sales workers, craft and related workers, plant and machine operators, and assemblers.

Routine task intensity – RTI index (Goos et al., Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014) has been used by numerous other scholars measuring occupational risk, social preferences, and voting behaviour (Autor and Dorn, Reference Autor and Dorn2013; Autor et al., Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2015; Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019; Thewissen and Rueda, Reference Thewissen and Rueda2019; Kaihovaara and Im, Reference Kaihovaara and Im2020). Routine cognitive, routine manual, nonroutine physically manual, nonroutine personal manual, nonroutine cognitive analytical, and nonroutine cognitive personal task inputs are derived per occupations classified by their ISCO − 88 4-digit codes and the log importance of routine measures minus log manual and abstract inputs rescaled to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. The ESS rounds under analysis here use ISCO − 08, which were downgraded to ISCO - 88 codes using values provided by Kaihovaara and Im (Reference Kaihovaara and Im2020). The least routinize/automated jobs are ‘religious professionals’ (RTI = −2.12), ‘education methods specialists’ (RTI = −1.59), and ‘sanitarians {inspectors and data collectors}’ (RTI = −1.36) while the most are ‘domestic helpers and cleaners’ (RTI = 1.89), ‘fashion and other models’ (RTI = 2.19), and ‘metal moulders and coremakers’ (RTI = 2.49). RTI is interacted with skill-level to differentiate high-skill routine from low-skill routine occupations.

Three hypothesized country-level labour market policies are included and data comes from the OECD (2020). EPL (permanent) measures the strictness of job dismissal regulations along four dimensions: i) procedural requirements before notice is given; ii) notice period and severance pay; iii) the regulatory framework for unfair dismissals; and iv) enforcement of unfair dismissal regulation. Higher values indicate stronger regulations in favour of employees (Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022). ALMP harmonized – Active labour market spending as % of GDP (OECD, 2020), covers spending on public employment services and administration, labour market training, measures aimed at helping youth transition from school to work, programmes to provide or promote employment for unemployed persons, measures for the disabled, and subsidized employment (Anderson, Reference Anderson2009). UNEMP harmonized covers traditional passive compensatory unemployment expenditure as a % of GDP (OECD, 2020). These %GDP-based measures are divided by unemployment rate to harmonize these measures per unemployed worker (Kweon, Reference Kweon2018). Summary and distributional statistics for all variables used in the analysis are displayed in Appendix Table 1.

Empirical analysis of occupational risk and voting

First to test the assumption that those with the predicted occupational risks discussed above do indeed feel subjective risk, a fixed effects ordinal logistic model with country clustered standard errors is run using a question for a rotating welfare attitudes module in ESS Round 8 on the subjective likelihood of having enough money to pay bills in the next year as the dependent variable. Here, the dependent variable is a 1–4 scale of the subjective belief that the respondent will not have enough money for necessities in the next 12 months ranging from ‘not very likely’ to ‘very likely’. Full results are displayed in Appendix Table 2.

Females, those with children, and younger individuals are more likely to believe they will need money in the coming year, while wealthier, public-sector workers, part-time workers, and the more educated are less likely to feel this risk. Key to the argument presented, all of the hypothesized variables that assume to capture labour market risk indeed are correlated with individuals indicating they would be more likely to not have enough money in the coming year: those whose work entails high levels of routine tasks, those in professions that have highly specific skills each are more likely to expect subjective income risk. Skill-level works against this subject fear, with those in higher-skill professions being less likely to hold such fear.

Another question on the welfare attitudes module asked respondents for their preferences of ‘spend[ing] more on education for unemployed at cost of unemployment benefit’. Using this question as a proxy for opinions towards active labour market policy over unemployment, a statistical difference (via both chi-square and t-test) is found between wage-earning PRRP and other wage-earning voters, with twice the percentage of PRRP voters being ‘strongly against’ such a shift in spending and also being less likely to be ‘in favor’ and ‘strongly in-favor’ of spending more on education for the unemployed. The associated gamma statistic is −0.1, indicating not only a statistical difference, but also one that is substantively detectable. Appendix Table 3 displays these cross-tabs.

The full regression results for PRRP voting are presented in Appendix Table 4. Column 1 presents logistic coefficients indicating whether a specific variable leads to an increased or decreased likelihood of voting for a PRRP, focussing on the interaction between skill specificity and labour market policies. Column 2 presents logistic coefficients indicating whether a specific variable leads to an increased or decreased likelihood of voting for a PRRP focussing on the interaction between skill level, RTI, and labour market policies. As expected, and in bold, those identifying with the ideological right are more likely to vote for PRRP while those holding favourable views towards immigration are less likely to do so. Also less likely to vote for the PRRP are public-sector workers, whose interests are not in alignment with the economic populist calls for a reduction in government bureaucrats. As compared to those with master’s degrees or higher, all other education levels tend to be more likely to vote for PRRP, except for those completing only upper-secondary or less, which previous research had found to be associated with abstention.

In turning to the key arguments, first there is no effect of the level of harmonized unemployment spending on the likelihood of PRRP voting. This is not entirely out of line with previous research that has found this spending to reduce the propensity of those unemployed voting for PRRP (Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022); the analysis here was focussed specifically on those currently employed. No level of occupational risk is associated with either mitigated or aggravated probabilities of supporting PRRP. On the other hand, active labour market policy spending appears to have a catalyzing effect on support for PRRP, with greater spending leading to greater support for PRRP. There are no significant differences between levels of specialization. While most skill levels are catalyzed by greater active labour market spending, craft, assembly, clerk, and service occupations almost reach significant levels being cushioned by those policies. Finally, employment protection legislation is found to both catalyze and cushion support for PRRP depending on the level of occupational risk. Investigating the conditional impact of this labour market policy will form the bulk of the remaining analysis section.

The upper tercile of Figure 1 Footnote 7 estimates predicted probabilities of voting for PRRP model 1 for a worker with median skill specificity (e.g., authors and journalists) and one with the 95th percentile of specific skills (e.g., a car/tax/van driver). These are graphed along the range of EPL across nations. In comparing across nations, when there is a greater amount EPL, we see that workers are less likely to vote for PRRP, yet we can observe that this effect is stronger for those with mid levels of skill specificity than those with very specific skills. The strength of this difference in effect is visible in the middle graph of Figure 1. Here, the marginal effect of skill specificity is graphed along the range of EPL with 95% confidence intervals. The hollow circles on the x-axis indicate where countries fall along this range. It becomes visible that in countries with high levels of EPL, those with greater skill specificity are more likely to support PRRP. This provides evidence for the self-reinforcing nature of this policy, as voters who particularly benefit from them, might feel the greatest threat from its repeal and thus would select PRRP over other parties less concerned with nostalgic producerism. In these cases, then, the presence of EPL can increase the support of PRRP of highly-specialized workers. The bottom tercile reports the marginal effect of EPL on the 1st−99th percentile range of skill specificity, with the hollow circles on the x-axis indicating where voters are placed. It is clear from this figure, as opposed to the catalyzing effect among the most-specialized in protected labour markets, that ELP indeed cushions support for PRRP, reducing the likelihood of that vote choice among low and medium levels of skill specificity.

Figure 1. Predicted and marginal effects of employment protection legislation and skill specificity.

A related divergent situation can be examined in the analysis of the conditional effect of employment protection legislation on routineness as a source of labour risk among different skill levels in assessing PRRP vote choice. Figure 2 separates the estimated marginal effects of employment protection legislation on each of the skill levels. The hollow circles on the x-axis identify the routineness of various occupations within the skill level. The upper left quadrant identifies those in elementary educations, such as domestic and hospitality cleaners, food preparation assistants, and mining labourers. Of note here is the positive marginal effect of EPL on voting for PRRP for those in the most routine (risky) low-skilled educations. Thus, one would expect a greater probability of voting PRRP from an all-else equal worker in a situation with greater levels of employment protection. Even with protection, these workers potentially are subject to status or income anxiety and support PRRP, who advocate on their behalf against labour market regulation. While these low-skilled workers are catalyzed by employment protection, of particular note is how those holding professional occupations are nearly all cushioned by the effects of EPL. Comparing an all-else equal worker, with greater employment protection, the worker is less likely to support PRRP. Recall, the professional class is often seen as winner of modernization and thus no matter how routine their occupation is, we can expect a moderated support for PRRP with EPL. The catalyzing and cushioning effects discussed above appear to counter one another for those in the middle of the skill distribution, as at no point is there an identifiable statistical catalyzing or cushioning effect of EPL on the PRRP for these workers.

Figure 2. Marginal effects of employment protection legislation & routineness on PRRP vote.

The impact of active labour market policies is almost universal in their catalyzing effect on PRRP voting. Figure 3 follows a similar format to Figure 2. Almost all of those with elementary occupations, technicians and associate professionals, and professionals, no matter their routineness, have a positive marginal effect of ALMP spending. In other words, the larger and more visible a nation’s ALMP programmes and spending, the more likely that most of these workers would support parties that tend to oppose them. This self-undermining feedback effect, however, is not felt by those in craft, assembly, clerking, and service occupations. Active labour market programmes tend to have a stronger effect on employment for those without tertiary education (Escudero, Reference Escudero2018), and so for this skill level, evidence would suggest that the catalyzing effects and cushioning effects counter on another with no overall effect of RTI or ALMP spending on these workers.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of active labour market policy spending & routineness on PRRP vote.

Conclusion

In a similar vein to a still-limited number of studies, this paper set out to examine whether government policy might mitigate the probability of voters experiencing labour market risk to vote for a populist radical right party (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019; Vlandas and Halikiopoulou, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022). Unlike these previous analyzes, however, the policy preferences of PRRP and their voters were included in theory building. As opposed to other forms of social policy previously examined, here it was argued that not only will all labour policies have a mitigating effect on PRRP voting propensities, but also that some policies might interact with one’s occupational position to catalyze further support for populist parties. It was found that workers most at risk (those with highly specialized skills or low-skilled workers in routine occupations) might actually increase their support for PRRP with strong government interventions in the economy.

The PRRP policy influence of ‘nostalgic producerism’ was highlighted as being one particular reason for this. As opposed to other parties of the mainstream left and right, PRRP are guided by a strong sense of defending ‘the makers’ and the producers in society from ‘the takers’ (Ivaldi and Mazzoleni, Reference Ivaldi and Mazzoleni2019) and argue for the regulatory protection of workers. It was then argued that high levels of employment protection legislation might then lead these voters facing occupational risk and status decline, through self-reinforcing, feedback to vote for the party that argues for the continuation of such policies. Relatedly, spending on active labour market policies may produce a self-undermining effect, especially for those inclined towards ‘nostalgic producerism’ as these types of programmes help those outside the labour market (‘takers’) and non-traditional workers (e.g., fixed-term workers, women, immigrants) and require an active role from (potentially inefficient and wasteful) government bureaucracies. Almost all occupational groups were found to be more likely to vote for PRRP under conditions of higher spending on active labour market programmes.

This paper found no effects for traditional forms of unemployment insurance on PRRP voting arguing that perhaps these policies both cushion and catalyze support for PRRP. Those facing occupational risks could potentially benefit in the future from generous unemployment insurance policies, but so too might undeserving non-traditional workers. Future research might more closely examine the relationship between PRRP and this traditional form of labour policy. In general, more fine-grained research is needed in the analysis of populist party platforms and campaigns to ascertain their stances on the labour policies examined above. This would provide further validation that indeed parties and voters in more interventionist economies find these issues to have high levels of salience in influencing their voting decisions (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2014). Some aspects of active labour market policy, for example, employment maintenance incentives, might be less objectionable than others like benefit administration or placement services. Additional research might also integrate the labour policies and preferences of populist left voters, as one might imagine this group to have different opinions on some of the labour policies discussed in this paper (e.g., unemployment insurance) (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Rathgeb and Sahm2022). Further research on the economic policies of populist parties should clarify these remaining questions.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this paper was presented at the 27th International Conference of Europeanists on the panel ‘Combining the Micro and Macro Explanations of Populist Voting in Europe’. The author thanks those participants for their assistance in framing the paper’s contributions and for the research assistance of Jonah Noaum and Benjamin Haußmann. The editors of the journal and three anonymous reviewers are also thanked for their careful reading of an earlier version of this manuscript. Financial support has been provided by the (FWF) Austrian Science Fund (project number: I 3793-G27).

Conflict of interests

The author(s) declare “none”.

Appendix

Table A1 Parties included in analysis

Table A2 Likelihood of not having enough money in next year

Random-Effects Ordinal Logistic Coefficients Displayed.

Standard errors clustered by country-election in brackets.

Ordinal-cut points omitted.

+P < 0.1; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Table A3 PRRP Voters More Opposed to ALMP spending over traditional unemployment

Pearson chi2(3) = 26.1654 Pr = 0.000.

Gamma = −0.0973 ASE = 0.037.

Table A4 Multi-level logistic regression results of PRRP vote

Random-Effects by country-election Logistic Coefficients Displayed.

Standard errors clustered by country-election in brackets.

***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1.

Table A5 Parties included in analysis