Introduction

Cymbals have resounded in a great range of musical contexts: The triumphant end of a Beethoven symphony, the driving pulsations of jazz bands, and the clashing strikes of Ottoman mehter bands signaling an incoming attack by Janissary infantrymen. Unlike the violin or guitar, however, the cymbal's pervasiveness in disparate musical contexts is closely intertwined with the generational experiences of one family—the Zildjian family—who currently claim a 400-year-old history as cymbal-makers. Whether onstage at Boston's Symphony Hall or Coachella, performers of diverse musical genres today frequently regard Zildjian cymbals as the gold standard of that instrument. Although lineages of acclaimed instrument makers have occasionally achieved notoriety that permeates mainstream cultural consciousness (one thinks of the Stradivari family and the 1998 film The Red Violin), the longevity and mobility of the Zildjians and the mythmaking around the family and their instruments have contributed to the cymbal's ubiquity.

A museum and exhibit space in the foyer of the current Zildjian cymbal factory in Norwell, Massachusetts, currently run by the fourteenth generation of Zildjian descendants, celebrates this longevity. The material artifacts and processes throughout the Zildjian factory render its visitor awash in different historical moments and places. The entrance is replete with the framed correspondence of Avedis Zildjian III, the first Zildjian to run the company in the U.S. after emigrating from the Ottoman Empire in 1909, a plaque commemorating Zildjian's official recognition as the United States’ oldest family-run business, a painted tree showing descendants who have run the Zildjian Company, and a mannequin in full regalia of the Ottoman mehter bands. Throughout the space of corporate offices are full drum sets played by or commemorating famous jazz and rock artists who championed Zildjian, and wall-to-wall spreads of distinguished drummers’ photos with Zildjian equipment.

Past and present are continuously superimposed on the approach to the factory space. Before entering, one sees the hammering tools used long before Zildjian incorporated assembly lines and industrial smelters into their process; upon entry, there are forklifts, conveyor belts, and the robots which hammer and spin the metal disks, mimicking the randomized patterns hammered by cymbal-makers for Ottoman mehter bands centuries ago. Next to the massive industrial equipment, “Zil-dj-ian” is written on the factory walls, the script of the company logo itself suggestive of Ottoman calligraphy. The gloss underneath explains that Zil is Turkish for cymbal, dj is Turkish for “maker,” and -ian is the Armenian suffix for “son of,” and that this name was bestowed upon Avedis I, the first in the Zildjian line, by Ottoman Sultan Mustafa in 1618. Nearby, a laser etches the Ottoman script signature of a Zildjian from generations past into a metal sheet lathed by hand and hammered by machine.

In this exploration of the iconic “Zildjian cymbal,” I investigate not only the materiality and narrativization of the instrument as an evolving transcultural and transhistorical object, but also ideas about history, culture, kinship, and nation that emerge from the Zildjians’ relationships to their cymbals. As I discuss in the following, historical narratives about the production of Zildjian cymbals describe the cymbal alloy being passed down for centuries from father to eldest son; they also suggest a natural evolution of the cymbal from Ottoman mehter to orchestral ensemble and eventually as an instrument in jazz and other popular music. However, such narratives overlook how sociopolitical oppression in the early twentieth-century Ottoman Empire and United States impeded certain articulations of ethnoreligious and minority identities, initiating Zildjian family members’ migration and leading to even greater reliance on transmitting cymbal-making knowledge to generate “Zildjian kinship.” In seeking to understand how the cymbal, particularly the Zildjian cymbal, achieved its iconic status and ubiquity in disparate musical genres, I argue that these organological and human kinships are co-constitutive: Reading the transmission of cymbal-making knowledge as an act of securing kinship tells a more complex story of transnational movement and belonging among and beyond the Zildjian family. Indeed, the branding of the Zildjian cymbal was more than simply promoting the moniker: I contend that the materiality and narratives of the cymbal are indicative of the experiences of the Zildjian family in the face of broader sociopolitical and assimilatory pressures in the Ottoman Empire, Turkish Republic, and United States.

Sifting through Zildjian promotional material, my brief correspondence with the current executive chair and president Craigie Zildjian, and published interviews with members of the Zildjian family involved in the business, I encountered a consistent narrative: An Ottoman alchemist discovers the alloy for the world's best cymbals; his kin carefully guard and diligently pass down the secrets of this craft; with each passing generation, Zildjian cymbals are adopted into ensembles ever further afield, accumulating new cultural meanings; they eventually cross the Atlantic, making their way into the hands of jazz and rock legends. Cymbals are highly marked in promotional materials as an instrument with an ancient and even exotic Turkish/Ottoman/Armenian past hearkening back to Constantinople in 1623; however, the cymbal is paradoxically rendered an unremarkable “humble object” in its assumed inclusion in military bands, marching bands, jazz bands, and orchestras.Footnote 1

Examining the meanings and relationships associated with the Zildjian cymbal is an exercise in confronting dissonances in representations of time. Considering how the cymbal sonically indexes a disparate range of musical ensembles and historical moments involves examining the Zildjians’ representations of the instrument's and their own historical pasts. Mikhail Bakhtin's notion of the chronotope (“timespace”) emphasizes the impossibility of discrete categories of time and space—time must materialize to be visualized, an exercise which necessarily requires space.Footnote 2 I consider the Zildjian cymbal an object that frequently facilitates the invocation of timespaces—that is, as a resonant material object that has circulated continents for centuries, the cymbal enables its human interlocutors to imagine certain timespaces (the Ottoman Empire, the jazz era, etc.) they associate with the cymbal as well as their own relation to those timespaces.

I also premise this exploration on an interpretation that understands things and matter (cymbal and human alike) as co-constitutive unfolding processes rather than isolated fixed states. Drawing inspiration from Edward Casey's discussion of the “gathering” power of a place which takes on “the qualities of its occupants, reflecting these qualities in its own constitution and description,” I regard the cymbal as a sort of “emplacing object,” with its own tendency to both gather and project resonances of its human and material interlocutors.Footnote 3 The meanings of a cymbal crash are constituted by the sensational contexts and paradigms of countless other (significant and signifying) living and non-living beings (or perhaps more appropriately, “becomings”) in concert with one another. In considering how the cymbal sonically indexes a disparate range of musical ensembles and the timespaces they resound for listeners, I draw inspiration from scholars who have called for recognizing instruments as subjects (rather than objects) of study, considering them as sites or agents of meaning-making and contestation.Footnote 4 Rather than concretize these contexts within the framework of static notions of “history” or “culture,” I examine materiality as a means of “confront[ing] a tradition of subordinating objects and images to culture and history.”Footnote 5 As Christopher Pinney writes, “The intransigence of the object has been submerged in the analytic surety of the power of humankind—that is, those who make culture and history, or those other frames within which we chose to dissolve the problem of the object and annul its enfleshed alterity.”Footnote 6 Through paying attention to materiality, we can approach the logics that allow a robotic arm to continue a 400-year-old cymbal hammering tradition as one of many “densely compressed performances” that enable us to construct ideas about timespaces and the meanings ascribed to them. We can discern how instruments, sensible (if not sentient) actors and performers in their own right, mediate understandings of human identities, kinship, institutions, and cultures.

In the following sections, I discuss the cymbal's shifting musical contexts and functions in Ottoman mehter bands, European orchestras, American jazz bands, and many other ensembles over the past four centuries, as well as the role of the Zildjians in this musical expansion. Then, I examine how twentieth-century negotiations of Zildjian kinship emerged in contentions over the authenticity and ownership of cymbal production. Finally, I consider how the assimilatory pressures of nation-states shaped narratives of cymbal production as well as the Zildjians’ mobilities. In doing so, I pay attention to the context of the ethnoracialization of minority populations in the late Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic as well as the struggle of Armenian migrants to the United States to be recognized as valid American citizens at the turn of the twentieth century. By approaching the cymbal itself as the main interlocutor of this exploration, I aim to bring to the fore the ways in which cymbals have sounded and resounded the mobility and kinships of its human creators.

The Cymbalic Narrative

The dominant narrative of the 400-year-old Zildjian Company, reproduced in its online interactive timeline, coffee table books, company museum and factory tour, and consumer discourse worldwide, is of an object circulating across increasingly extensive culturally bounded timespaces. Achieving the Zildjian cymbal's present iconic status meant not only preserving its historical lore, but also describing its emerging ubiquity. In this narrative, the Zildjian cymbal originates as the Ottoman mehter instrument produced in the early 1600s by an Armenian alchemist in the Ottoman court and used to induce psychological terror during attack. By the mid-twentieth century, it appears in the form of the high hat and ride cymbal. In fact, by referring equally to the instrument performed by mehter ensembles, orchestral percussionists, jazz drummers, rock musicians, and others, the word “cymbal” belies the extent to which this term has become a hypernym, ever-expanding to facilitate the inclusion of its disparate physical and sonic manifestations, performance techniques, and musical functions.

Cymbals were a signature feature of Ottoman mehter music, which could involve dozens or hundreds of musicians playing small and large kettledrums (nakkare and kös), a bass drum (davul), wind instruments (zurna and boru), the shaken percussive Turkish crescent (çoğan) as well as cymbals. Mehter ensembles continue to be strongly associated with the Ottoman military forces, as they accompanied the elite infantry corps known as the Yeni Çeri (“New Army,” often rendered as “Janissary”) into battle; however, the tendency for Western observers to refer to this musical tradition as “Janissary music” or “Ottoman military music” overlooks the fact that mehter ensembles also frequently performed separately in other official peacetime contexts such as for the greeting of diplomats and political representatives and in guild processions.Footnote 7 The cymbals of these ensembles were smaller in diameter and thus more portable than standard symphonic orchestral cymbals; however, both are typically played in pairs and secured with handstraps in the center of the bell.Footnote 8 Mehter cymbals were typically played in pairs in one of two positions: Dikçalış (“vertical playing”), in which the cymbal player holds one cymbal in each hand and strikes them together, or yatıkçalış (“horizontal playing”), in which the cymbal player (either seated or on horseback) holds one cymbal and strikes it against the other in his lap, leaving one hand free.Footnote 9 The mehter cymbal also took on paralinguistic functions, relaying information to initiate the start of an attack or to encourage troops on the battlefield. Slightly smaller cymbals (called halîl) were also used contemporaneously in Ottoman Sufi lodges to accompany religious music using a technique called halîlevî, in which the cymbals are not brought far apart after being hit together softly to sustain their resonance.Footnote 10 Cymbals served and continue to serve a sacrosanct role in many Armenian churches, where the instrument (ծնծղա, transliterated from Armenian as tsntsgha) provides an essential component of religious ceremonies along with other ceremonial percussive instruments, including the liturgical flabellum kshots (կշոց) and censer burvar (բուրվառ) with bells that accompany certain liturgical chants.Footnote 11 As of 2017, a pair of cymbals made by the Zildjian family were in active use at the Armenian Church of Surp Takavor in the Kadıköy district of Istanbul.Footnote 12 Cymbals additionally featured prominently in secular and informal performance in the Ottoman Empire. Finger cymbals (parmak zili or çalpara) were commonly used in Ottoman courtly contexts by performers such as the often female-presenting male köçek and female çengi; they also featured regularly in performances by professional dancers and musicians (largely non-Muslims such as Romani, Greeks, and Armenians) in public entertainment sites such as meydan (public squares), fairgrounds, and street intersections.Footnote 13

Although the symphonic cymbal is often used to accent or add effects and colors in a composition (most notably, at dramatic climaxes), in mehter music, the cymbal (along with percussion instruments kudum and daire) is a fundamental component that gives coherence to the entire musical creation through articulating its usul (rhythmic cycle), thus providing a sense of orientation for the entire ensemble. Polish-origin Ottoman interpreter and musician, ʿAlī Ufuḳī Bey (born Albert Bobowski, 1610–1675), a prolific documentarian of Ottoman court life, music, and language, indicated the centrality of the zil in the mehter ensemble: “If you are to enter the place of the musical masters, first learn to play all of the usuls with the kudüm, daire, and cymbal” (Figure 1)Footnote 14.

Figure 1. Image of a zilzen (cymbalier) in the Ottoman military, as illustrated in Mahmud Şevket Paşa, L'organisation de l'armée ottomane [“The Organization of the Ottoman Army since 1826”], Mekteb-i Harbiye Matbaası (1907).

This primary function of the zil seems to have been generally lost on Europeans encountering mehter music during the Ottomans’ many military incursions, from the 1453 conquest of Constantinople (the seat of Christianity under the Byzantine Empire) to the 1529 and 1683 sieges of Vienna. Particularly following the Ottoman Empire's failed siege of Vienna in 1683, denigrating the Ottomans bolstered the development of European identity.Footnote 15 Drawing on sources describing European encounters with mehter music as well as its imitations at European courts, Harrison Powley and Edmund Bowles note that European observers in this period frequently referred to the “noisiness,” “ugliness,” “tonelessness,” and general inferiority of mehter music.Footnote 16 In the seventeenth century, mehter became “the music by which Europeans judged all ‘Turkish music’” and contributed to cementing a widespread fear of Turks generally in the European imagination.Footnote 17 The psychological terror inflicted by the mehter's sound created a “lingering trauma” Europeans associated with Turks and contributed to a widespread practice of parodying mehter (alongside “wild men, pygmies, or ‘Indians’”) in European court festivals and pageants. European nobility and court musicians from the 1500s through the 1700s frequently dressed up flamboyantly in such pageants to enact the defeat of Ottoman sultans and infantry.Footnote 18

As Eve R. Meyer has suggested, as the Ottoman Empire's military and economic dominance declined and diplomatic relations warmed (particularly after the Ottoman defeats in Europe at the end of the seventeenth century), a cultural fascination with “Turquerie” engulfed much of Europe.Footnote 19 Particularly after the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 and Sultan Mehmed IV's presentation of a full mehter band to King of Poland and Elector of Saxony August II, many European courts sought to produce their own “Turkish” ensembles with musical instruments from mehter. In 1725, Empress Anne of Russia sent a musician to Constantinople to assemble her own Turkish-style military band; in the 1740s, Austrian and French rulers also formed similar ensembles, and soon many other European armies followed suit. These ensembles were frequently fashioned after European exoticization of mehter and Ottoman life (often featuring “blackamoors in gaudy oriental garb”) and prominent in musical accompaniment and dramatic entertainment at courtly festivals and celebrations (including royal weddings).Footnote 20 These ensembles’ instrumentation and sonorities were noted (and even derided by both Turkish and European observers) for varying significantly from that of the Ottoman mehter.Footnote 21 Nonetheless, cymbals would continue to contribute the martial associations of these and subsequent military bands, as well as the signification of Turkishness in European art music compositions of the period.Footnote 22 Incidentally, Sultan Mahmud II's major reforms of the Ottoman military and abolition of the elite infantry corps in 1826 prompted the replacement of mehter with Muzıka-i Hümayûn (the Ottoman Imperial Band), an ensemble modeled on the western European military band tradition inspired by the European ensembles that had initially incorporated musical elements from mehter (including cymbals) as a result of fear, mockery, and imitation of the Ottomans.

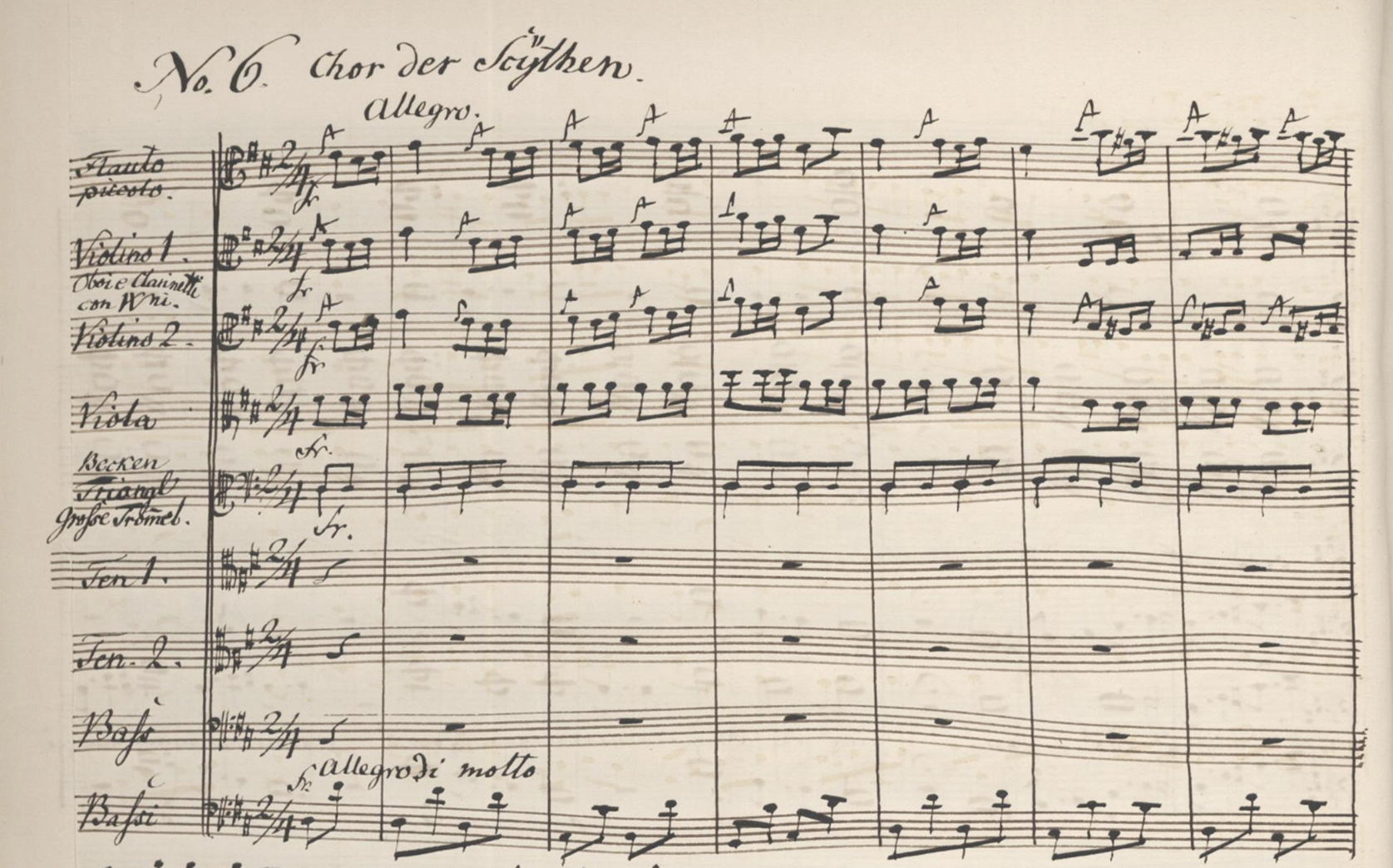

Nicolaus Adam Strungk's 1680 opera Esther and Domenico Freschi's Berenice vendicata (1680) mark perhaps the earliest uses of cymbals and bass drum, but it was only from the mid-eighteenth century that a widespread fascination with Ottoman military band music swept up composers of the European art music tradition such as Christoph Willibald Gluck, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Franz Joseph Haydn.Footnote 23 The bass drum, cymbals, and triangle were often treated as a unified element known as the “Turkish music instruments” (seated in a group separately from the timpani) that contributed an iconic tone color, typically in the loudest movements of a composition such as the first and last movements of a symphony or overture and finale of an opera.Footnote 24 Some scholars have underscored the homogeneous treatment of bass drum, cymbals, and triangle in compositions of this period, noting the tendency for percussion parts (often merely “skeletal notations”) to be purchased as supplements to orchestral part sets (Figure 2).Footnote 25

Figure 2. Excerpt of the Chorus of Scythians from Gluck's Iphigenia in Tauris (the 1781 German-language version of his 1779 French opera “Iphigénie en Tauride”). As seen in the fifth stave, the composer indicated a single part notated for cymbal, triangle, and bass drum (“Becken, Triangl, Große Tromel”).

Generations of Zildjians actively responded to and promoted demand for cymbals in European contexts, particularly as a larger symphonic ensemble format, concern with musical expressivity, and public concert-going became prevalent across Europe. As cymbals became a familiar part of the “Turkish music” instrumental group in the expanding European orchestra, Zildjian cymbals, produced in larger sizes and played with new techniques for aesthetic effect, achieved a conspicuous place in the ensemble. Hector Berlioz's 1827 Requiem required at least ten pairs of cymbals, and Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) (1848–1876) cycle and other operas featured cymbals extensively, played with a variety of methods to convey dramatic nuances that had previously seemed beyond the scope of musical expression. Berlioz, who recalled the “profoundly violent shock” he felt hearing cymbals introduce a troupe of cannibals in Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride (Iphigenia in Tauris), describes in his orchestration treatise how he himself used cymbals as part of the musical fantastique to convey a “noise…of extreme ferocity” signaling “horror or catastrophe.”Footnote 26 He includes a pair of cymbals in his outline of the ideal instrumentation for the contemporary concert orchestra, and writes about the musical possibilities of utilizing the cymbal separate from the bass drum, including striking a suspended cymbal with a sponge-headed stick to create a shimmer, rapidly sliding one cymbal against another (a technique he notated with the instruction sec), soft cymbal crashes, a two-plate roll achieved by simultaneously rubbing and rotating the cymbals one around the other, quickly repeated clashes, and specifying durations for the instrument to ring or whether to muffle a crash.Footnote 27 Wagner's operas feature not only cymbal crashes to convey dramatic climaxes but also suspended cymbal shimmers and rolls that communicate the power and curse of the gold ring (in Das Rheingold) and the impact of a mysterious blessing (Die Walküre). More than mere exoticized noise, such uses of the instrument indicated the absorption, transformation, and even invention of meanings associated with the cymbal.

Berlioz wrote to his acquaintances of his frustration in encountering cracked or notched cymbals in the orchestras of Germany: “It was always a great source of wrath to me, and I have sometimes kept the orchestra waiting half an hour, being unwilling to begin a rehearsal before they brought me a pair of really new cymbals, really quivering, really Turkish, as I wished them to be…they do not seem to suspect the effects that can be drawn from them…the players are far from knowing all their resources.”Footnote 28 As the Zildjian Company website explains, both composers’ specific requests for Zildjian cymbals further elevated the Zildjians’ reputation in European art music circles. Rather than acknowledging prior Ottoman–European political, military, and musical exchanges, however, the Zildjian narrative credits the resourcefulness of antecedent patriarchs such as Kerope II, who was said to have built a 25-foot schooner to transport his cymbals from Constantinople to Marseilles and London for the World Trade Fair in 1851.Footnote 29 Zildjian cymbals began to attract international recognition and accumulate awards, including the Honorable Mention at the 1867 World Exhibition in Paris; notably, before 1851, they had been popularly referred to as simply “Turkish cymbals.”Footnote 30 Impressed by their utilization in Gluck's opera Iphigénie en Tauride, French musicologist Oscar Comettant described encountering the cymbals at the Paris World Exhibition:

Of all the musical instruments on exhibit, it was the cymbals which really deserved note and the undivided attention of the entire music world, they attracted such widespread comment. The resonant, high-pitched and prolonged ringing sound are truly valuable qualities. They may be played with drums or successfully on their own…The Turks do not wish to divulge the secret of the metal compound used in manufacturing these cymbals. Assisted by his brothers, the cymbal maker Kerope Effendi, receives export orders for 1300–1500 pairs of cymbals per year; each pair costing between forty and fifty-two thousand francs.Footnote 31

Showcasing the connections between Zildjian cymbals and European art music composers remained an important publicity strategy through the twentieth century. In a 1949 interview, Avedis Zildjian III bragged that “Harry Edison, the cymbalist for [conductor Arturo] Toscanini, has three chests full—about 200 [Zildjian cymbals].”Footnote 32

With the rise of jazz, the cymbal was again reinvented as a means of orienting a musical ensemble. As Avedis Zildjian III (1889–1979) started a cymbal factory in the U.S. at his uncle Aram's behest in 1927, the cymbal of early jazz pioneers was still a relatively small instrument. Collaborating with virtuoso jazz drummers, particularly Gene Krupa, Chick Webb, and Papa Jo Jones, Avedis III developed the much thinner cymbal that would become the hi-hat, ultimately developing many new cymbal designs, sounds, and functions as well as terminology to describe them: Splash, ride, crash, pang, ping, bounce, and sizzle. Avedis III's son Armand, Zildjian Company president from 1977 until 1999, recalled, “Gene had many great ideas about playing cymbals, such as using them as the timekeeper on the kit in place of the snare drum.”Footnote 33 In a sense, responsibility for ensemble coherence and orientation returned to the cymbal for the first time since the Ottoman musical context.

The Avedis Zildjian Company was able to survive the rations on metal during World War II as they fulfilled orders for cymbals from the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps marching bands and the British Admiralty.Footnote 34 The cymbal's reinvention after the war again transformed the instrument's role in musical ensemble. In addition to a time-keeping role, Zildjian cymbals’ new and explosive diversity of sounds and effects contributed to the instruments becoming an essential element in drum kits. This versatility also afforded drummers a new positionality as virtuosi.Footnote 35 Drummer Peter Erskine recalled that the cover of the “Rich Versus Roach” LP featured two drumsets “both with Zildjian cymbals topping them off, and both being played by the two towering titans of drumming: Buddy Rich and Max Roach….The genius of Max Roach gave these drum battles an entirely new sound, however. Max soloed more like a saxophonist or trumpeter than (merely!) a drummer.”Footnote 36

Under Armand Zildjian, the Zildjian Company continued generating new cymbal varieties (each with its own sobriquet) in collaboration with leading drummers; the company also regards the Beatles’ televised performance on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964 as having catalyzed an explosion in demand for the company's cymbals.Footnote 37 Today, Zildjian cymbals remain among the most popular cymbal choices for drummers, and the company sponsors over 200 prominent drummers and percussionists as members in the “Zildjian Family of Artists.”Footnote 38

Zildjianealogy: Debating the Authenticity of Kinship and Production

These days, as the cymbals are shaved down infinitesimal amounts by master lathers in the Zildjian factory in Norwell, Massachusetts, golden shavings accumulate on the ground, then are collected and recast with newly added ingots of copper, tin, and silver to form the treasured secret alloy. This process has been passed down from Zildjian to Zildjian over generations. As reported by factory workers, these shavings, along with cymbals deemed sub-standard, are returned to this literal melting pot. Upon hearing this, we might fantasize that remnants of the earliest Zildjian instruments are mixed in with this blaze, and perhaps even that the alloy the Zildjians used to cast the first church bell in the Surp Giragos Armenian Church in present-day Diyarbakir, Turkey, now resonates in the splash and ride cymbals churned out by the Norwell factory.Footnote 39

Indeed, in the Zildjian's fiery foundry, as all returns to molten metal, old mixes with new and artisanship coalesces with the automated. After casting and lathing, a robot spins and hammers cymbals, impressing upon each one a pattern mimicking the randomness of the imprint previously left by the hammers of the smiths producing cymbals for the mehter. An article in 1949 in the Lowell Sun featuring Avedis Zildjian III and the Zildjian cymbal company notes that the thousands of cymbals the twelve men in the factory produced annually required forty-five days being hammered by hand four to six times; Avedis remarked, “It isn't easy to hammer cymbal…It takes a man at least six years to become skillful.”Footnote 40 Hammering the cymbal compresses the metal more densely in the hammered areas, disrupting the sound waves such that cymbals with larger hammered marks create a sound that is considered “warmer,” “darker,” “trashier,” and “dirtier.” Robotic hammering is more time-efficient than hand hammering, which is believed to guarantee that no two cymbals will be identical. Automation in the modern-day factory simulates the historical practice for each new cymbal made (albeit perhaps without the randomization guaranteed by human error). A patent the Zildjian Company filed in 1972 for a metal percussion instrument buffing method declares the new machine “more reliable and much faster” than historical cymbal-making processes, which “consume[d] perhaps 30 minutes per cymbal.”Footnote 41

In streamlining and codifying the production process through simulations and perfections of human processes, does the machinery still imbue the cymbals with “authentic” Ottoman (and/or Turkish and/or Armenian) workmanship? Zachary Sayre Schiffman posits a reliance in the present upon a “‘living past’ that was, at one and the same time, different from the present and of vital importance to it as a cultural norm.”Footnote 42 A modern reliance on differentiating the past from the current moment enables the Zildjians, “America's oldest family-run business,” to produce new cymbals that derive value from historical production practices and resonant timespaces (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Robotically hammered K. Zildjian Constantinople cymbals. Photo by author.

The past has measurable value. Online forums such as r/drums on Reddit frequently feature posts from users sharing how they incorporate Zildjian cymbals into their drum kits, debating the superiority of certain lines and vintages of Zildjian cymbals, and asking for assistance identifying and dating their Zildjian cymbals; the latter pursuit has led to at least one article and multiple websites dedicated to methodically analyzing Zildjian trademark stamps for the purpose of cymbal identification and valuation.Footnote 43 Such assessments rely upon distinctions such as size, positioning, ink usage, and script of the cymbal's stamp to evaluate the instrument's manufacturing era and place, product line, intended market, quality, and suggested current retail value. The valuation of cymbals based on their vintage and place of manufacture creates a taxonomy of stratified timespaces (centuries, continents, cultures, and religions) made tangible in the materiality of the cymbal. As I argue in this section, for the Zildjians as cymbal-makers, producing this “emplacing object” entailed creating and curating a consumable past. I consider how claims about the instrument's authenticity, proprietorship, belonging, and national origin shaped the Zildjians’ own demarcation of kinship. As I will argue, twentieth-century proprietary claims on the Zildjian cymbal are indicative of the ethnoracializing forces that catalyzed the mobility of its human interlocutors and have shaped their relationships to notions of history, culture, and nation.Footnote 44

The Zildjian Company traces both the family's and cymbals’ lineage using historical documents and artifacts tying them to an Armenian heritage in Constantinople, the cultural heart of the Ottoman Empire. The company narrative projects an unbroken chain of inheritance from a fabled seventeenth-century alchemist, with fathers passing down the secret alloy to sons (and in the twentieth century, daughters). Although the Zildjian Company affirms Avedis Zildjian I as the innovator of the alloy and cymbals, historian Pars Tuğlacı writes that the earliest known member of the family was his father, Kerope, who migrated from the Black Sea coast to Samatya, a neighborhood of today's Istanbul (formerly Constantinople). According to Tuğlacı, “[Kerope] was originally a copper smith who won such repute that he was appointed Chief Cauldron Maker to the Ottoman Palace.”Footnote 45 Legends from Samatya claim that Kerope grew up in the Surp Kevork Armenian church orphanage in that neighborhood, where his enthrallment with the church bells laid the groundwork for his lifelong vocation.Footnote 46 Tuğlacı asserts that Kerope, who lived until the age of 96, established the first Turkish cymbal workshop in 1623 in Samatya and passed it on to his son Avedis, who discovered the famous secret alloy that would win acclaim for himself and future generations of Zildjians.Footnote 47

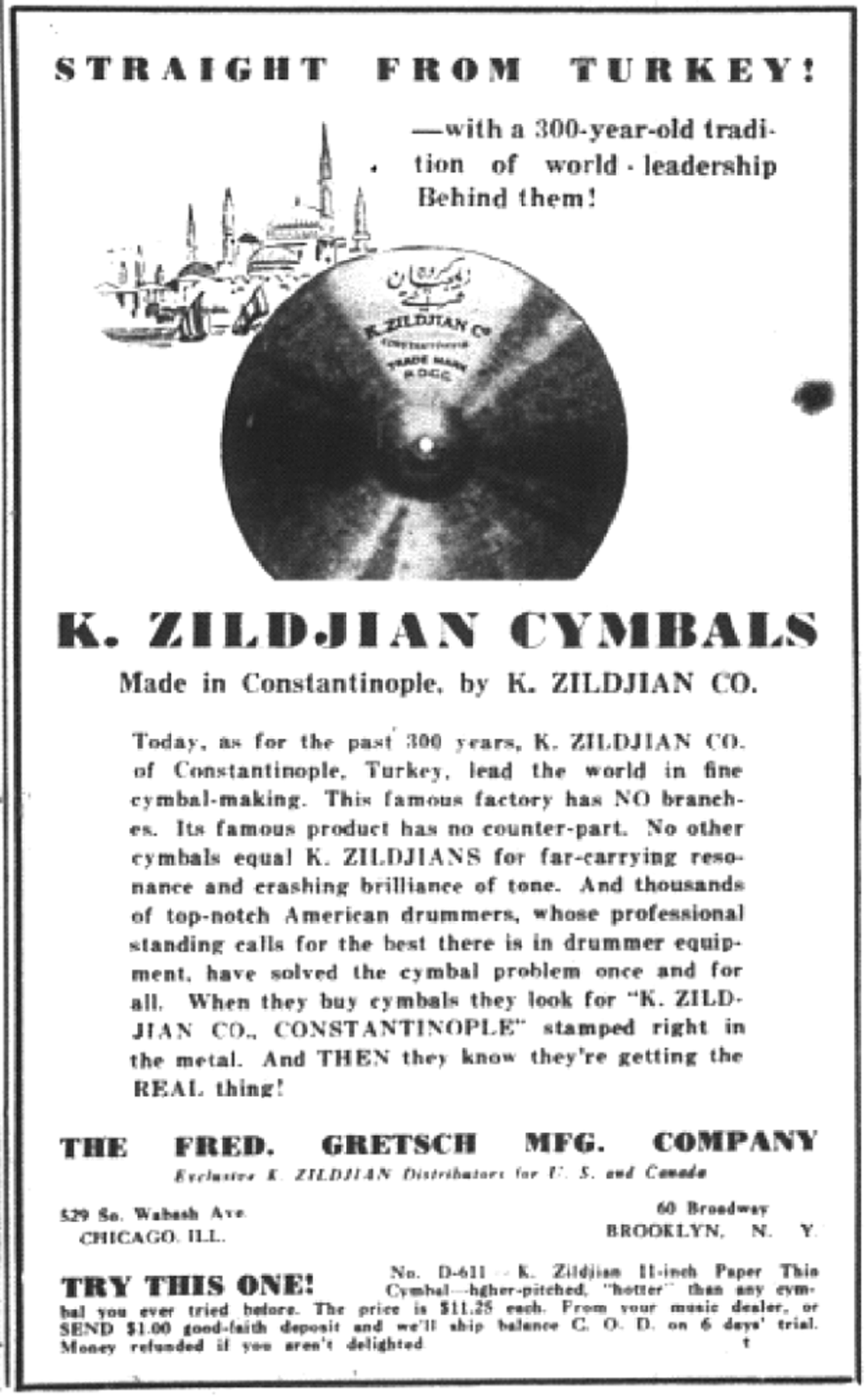

However, by the twentieth century, the existence of cymbal-making operations by different Zildjians and their collaborators motivated contested claims of authenticity and superiority based on alternative claims about the Zildjian lineage. Advertisements for Zildjian cymbals from the mid-twentieth century (some published nearly 20 years after Turkey's capital had been officially renamed Istanbul) illustrate further (Figure 4):

Today, Avedis Zildjian cymbals are the only genuine, old-time Turkish cymbals made by Zildjian in any part of the world by that famous 300-year-old secret Zildjian process…[since 1623]. (Figure 5)Footnote 48

Today, as for the past 300 years, K. Zildjian Co. of Constantinople, Turkey, lead the world in fine cymbal-making. This famous factory has NO branches…And thousands of top-notch American drummers, whose professional standing calls for the best there is in drummer equipment, have solved the cymbal problem once and for all. (Figure 6)Footnote 49

Direct from Turkey and the 300 year old factory of K. Zildjian Constantinople…World's Great Symphony Orchestras and Bands Use “K. Zildjians”…No other cymbals can match the rich, brilliant, exciting tones of K. Zildjians—the world's standard of cymbal quality since 1623.Footnote 50

Figure 4. 1937 advertisement for Avedis Zildjian Cymbals DownBeat (September 1937), 18. Provided by the Zildjian Company.

Figure 5. 1937 advertisement for K. Zildjian Cymbals, distributed by the Fred Gretsch Manufacturing Company, DownBeat (September 1937), 30. Provided by the Zildjian Company.

Figure 6. 1948 advertisement for K. Zildjian Cymbals, distributed by the Fred Gretsch Manufacturing Company, Music Educators Journal 34(3) (1948). Provided by the Zildjian Company.

In these advertisements, the resonance of the Zildjian cymbal is imagined to evoke Constantinople in 1623, contemporary Turkey, New York City and Chicago in the 1930s and 40s, the Euro-American symphonic musician, a 300-year period, an Ottoman signature, and a mosque. These advertisements animate the idea of a present from which the viewer can recollect simultaneous still frames of various frozen pasts. Selling the cymbal becomes an act of producing history, affirming that the material instrument enables access to an associated collection of flattened scenes from static pasts.

Although the modern Zildjian Company appears monolithic, in the early 1900s K. Zildjian and A. Zildjian Companies (named for their respective founders Kerope and Avedis) were separate companies operating in two different countries, only one of which was Turkey; the Gretsch Company served as the sole U.S. distributor for the Turkey-based K. Zildjian Company until the U.S.-based A. Zildjian Company acquired it in 1977, merging to become the Zildjian Company. As in the above advertisements, both K. and A. Zildjian Companies underscored the authenticity of their product's linkages to Turkey and an origin in 1623. K. Zildjian's operations perhaps marked the first time a woman (Victoria) had been charged with keeping the secret alloy formula; she then passed it along to her sister's husband Mikhail Dulgaryian, a transference outside the typical Zildjian chain of inheritance by the oldest son.Footnote 51

After opening a Bucharest-based Zildjian cymbal company in the early 1900s and operating it for around two decades, Aram Zildjian sought to transfer the operation to his Massachusetts-based nephew Avedis Zildjian III in 1927. The current Zildjian Company factory tour asserts this is because the aging Aram wanted to pass on the mantle to his closest living relative. Hence, he traveled to Massachusetts to help Avedis start what would be incorporated as the “Avedis Zildjian Company.” According to the 1958 lawsuit filed by Avedis’ U.S.-based company against Gretsch, the U.S. distributor of the Turkish-based K. Zildjian Co. of Constantinople (by that time, Istanbul), the cymbals produced at Aram's Bucharest-based Zildjian factory were of subpar quality.Footnote 52 The emergence of two separate companies, based respectively in Turkey and the United States but each run by Zildjians and purporting to sell “authentic” Zildjian cymbals to an American market, fueled tensions between the firms.Footnote 53 In 1929, a Massachusetts district court consent decree ruled that Gretsch, the Turkish K. Zildjian Company's U.S. distributor, was the sole owner of the trademark “Zildjian”; the court also ruled that Avedis’ new U.S.-based cymbal company could not use the names “A. Zildjian Co.” and “K. Zildjian Co.” or represent that its cymbals were made by a process similar to that used by the Turkish company.Footnote 54 Disputes over the rights to trademarks and patents between the two companies continued to erupt both in legal battles over whether “Genuine Turkish Cymbals” could simultaneously be “Made in the USA”; they also emerged in the companies’ advertising asserting unbroken inheritance of the secret production process. After decades of protracted litigation between the Avedis Zildjian Company and Gretsch, in 1968, the former purchased the K. Zildjian Company trademarks and negotiated with Baldwin (which owned Gretsch) to secure distribution rights.Footnote 55 This resulted in the eventual consolidation of what would become today's Zildjian Company, the 1968 opening of a Canada-based factory (which in 1980 would become the headquarters of the Sabian cymbal company), and the 1977 closure of the Turkish Zildjian operation (and its reinvigoration by its former apprentices Agop Tomurcuk and Mehmet Tamdeğer).

Utilizing the Zildjian lineage to project an authentic and therefore “superior” product motivated an array of attempts to demonstrate kinship through relationship to the Zildjian family and secret alloy. When the Turkish government banned surnames with the Armenian suffix -ian (“son of”) during the institution of the Surname Law in 1935, Mikhail Dulgaryian changed his surname to Zilçan (meaning “cymbal bell” and pronounced nearly identically to “Zildjian”).Footnote 56 Zildjian contenders also included Karekin Zildjian, who was apparently considered to be outside the line of inheritance but in 1907 moved to Mexico City, where he attempted to start his own rival Zildjian cymbal factory. The somewhat apocryphal-sounding and oft-enumerated saga suggests that relation to and transmission of the alloy can affirm and exclude kinship.Footnote 57 Indeed, the ultimate result of Karekin's exploits suggests a retribution by the alloy itself, as drummer and journalist Hugo Pinksterboer reports: “His experiments ended abruptly in an explosion that tore his head off and ‘encased his body in molten bronze.’”Footnote 58 In this portrayal, being rightfully bestowed with the alloy empowers more distant kin and grants possession of the Zildjian name, although blood relatives who do not receive these gifts are punished spectacularly. These kinships—based on familiar and metallurgic ties—are thus co-constitutive, and the convergences of their lines of ascent form the plane of tradition, namely the myth and history of the Zildjian Company.

Particularly illustrative is the case of Robert Zildjian (uncle of current Zildjian Company executive chair and president Craigie), who is portrayed in the Zildjian Company factory tour as having effectively betrayed the Zildjian family legacy by starting his own successful cymbal company, Sabian; now, on the family tree painted on the wall of the front space in the current Zildjian factory, Robert's branch is covered in mushrooms. It is interesting to note that Robert Zildjian further inscribed kinship into his commercial endeavors as he derived the name Sabian from the first names of his children (Sa- for Sally, -bi- for Bill, and -an for Andy); at the same time, like Zildjian, Sabian contains the Armenian suffix -ian, which, as mentioned above, means “son of.” By creating his own line of alloy derived from but separate from that of Zildjian, Robert nonetheless draws upon his own lineage as Zildjian kin while continuing to instill the value of kinship and lineage in his own brand's moniker.

Even those outside the family tree have invoked the lineage of the Zildjian cymbal to beneficially position themselves and their products. Istanbul Agop and Istanbul Mehmet cymbal companies were founded by Agop Tomurcuk and Mehmet Tamdeğer after the 1996 dissolution of their partnership as the 1980-founded Zilciller Unlimited Company (shortly thereafter renamed Istanbul Zilleri). Agop Tomurcuk was born in Samatya in 1941 and worked in Mikhail Zilçan's workshop (the Istanbul-based K. Zildjian Company) from the age of eight or nine, as did his brothers Oksant and Garbis.Footnote 59 Mehmet Tamdeğer apprenticed at this Zildjian workshop consecutively, and like Agop, became a skilled cymbal-maker. Both Agop and Mehmet claimed to have observed the secret alloy formula and even improved upon it in their own workshops, experiences both companies incorporate into their brand narrative. In a 2014 interview, Agop's son Arman (who currently co-operates Istanbul Agop with his brother Sarkis) commented, “We believe the Zildjian family is at the foundation of our success today.”Footnote 60 Although neither Agop nor Mehmet were part of the Zildjian family lineage, their company narratives extol the quality of their cymbals by representing their creators as professional progeny of the Zildjian family and their alloy as an extension of that metallurgic legacy.

Mobility, Assimilation, and the Cymbal

The expanded inclusion of the cymbal in American popular musical genres is frequently attributed to Avedis Zildjian III's 1909 migration to the United States alongside many thousands of other Armenians in the early twentieth century (in total over 60,000 by 1914).Footnote 61 This ultimately proved to be a fortuitous business move placing Avedis in the orbit of swing and jazz music pioneers; it also coincided with the mass exodus of Armenians from the Ottoman Empire in the early twentieth century amidst mounting systemic opposition and violence. For the Zildjians themselves, commercial success has entailed navigating their own ethnoracialization, particularly as it accorded with dominant ideologies of national identity formation, within the Ottoman Empire, Turkish Republic, and United States. Historically contextualizing the force of these nation-states in shaping narratives and mobilities of the Zildjians over the last century provides a new dimension to the success story.

The final decades of the nineteenth century saw “a rise in the national consciousness of the [Ottoman] empire's Armenian population,” which had formerly coexisted as a millet (a state-designated ethnic minority based on religious difference) with the many other ethnic populations under Muslim rule in the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 62 State designation as a millet afforded Armenians religious freedom and the ability to establish communal identities within the broader Ottoman population, but also entrenched their status as the Christian gayrimuslim (non-Muslim) “other” through overtaxation and other forms of discrimination. As urban Armenian intelligentsia sought constitutional reforms and improved status for Armenians, they extolled, romanticized, and increasingly connected with an Armenian peasant class and culture with which they previously had had little contact.Footnote 63 The 1876 ascension of Sultan Abdulhamid led to violent conflicts and brutal suppression of rural uprisings encouraged by Russian Armenian revolutionary groups, which only intensified following military engagements with Russia in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) and World War I. Fearing Armenian allegiance with European and Russian powers, between 1894 and 1896, Ottoman administrators executed systematic massacres targeting eastern Anatolian villages and Constantinople in which an estimated 100,000 Armenians died.Footnote 64

This hostile and oppressive environment likely motivated Aram Zildjian's membership in a group of Armenian nationalists revolting against the Ottoman government, as he allegedly participated in a failed attempt to assassinate Sultan Abdulhamid II with a suicide carriage outside a mosque in Constantinople in 1905. It appears that the political danger motivated Aram to flee to Bucharest, where he opened a Zildjian cymbal factory and remained for decades.Footnote 65 Hostilities only intensified after the political reformers known as the “Young Turks” stripped the sultan of his powers in 1908 and reinstated the previously established constitutional government. The movement's most radical Turkish nationalists formed the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), assuming one-party rule in 1913. Following military defeats in the 1912–1913 Balkan Wars, beginning in 1915, the CUP deported and executed hundreds of Armenian intelligentsia from Constantinople and oversaw the systematic exile and killing of an estimated one million Armenians across the provinces of Anatolia. Many historians have situated these campaigns as part of a broader pattern of genocide in the former Ottoman Empire waged against ethnoreligious minorities including Armenians as well as Greeks, Jews, Assyrians, and Kurds.Footnote 66

This hostile climate instigated a mass exodus of Armenians to the United States, where in the mid-1800s American missionaries had sent Armenians to undergo theological training (the first of multiple major waves of Armenian migration over the past century that have resulted in substantial diasporic populations in New England as well as Los Angeles, Lebanon, Iran, and Russia).Footnote 67 Avedis Zildjian III migrated to Massachusetts in 1909 and worked for a confectioner before opening his own candy factory; his naturalization witnesses Simon H. Shooshan and Michael Hagop Hintlian were also Armenian confectioners who had migrated from the Ottoman Empire and become naturalized U.S. citizens. Although Simon had been running a confectionary in New Hampshire as early as 1894 and thus migrated at least 15 years earlier, Michael in fact had arrived on the same ship as Avedis in 1909 and applied for naturalization in 1911 just one day earlier. In a 2015 interview, Avedis’ granddaughter Craigie Zildjian explained that the threat of Avedis’ conscription by the Turkish army motivated his migration, commenting, “There was a lot of religious tension in that part of the world at that time, a lot of conflict. This was his way out.”Footnote 68

Although Aram had fled to Bucharest, the K. Zildjian Company's operations out of the Constantinople neighborhood of Samatya remained active (under the supervision of Kerope Zildjian II's daughter Victoria and her nephew Mikhail Dulgaryian) despite the intimidation of and violence towards Armenians in the early 1900s. Indeed, unlike the later waves of unskilled and semi-skilled Armenian migrants from Black Sea villages as well as inner Anatolia seeking work in Constantinople from the 1840s onward, sources claim that the Zildjian family had migrated from the Black Sea region of Trabzon at least two centuries earlier and established strong relationships with the Ottoman elite through their skilled craftsmanship.Footnote 69 Nonetheless, historian Talin Suciyan describes how, following the violent campaigns waged on Anatolian villages, the Armenian community in Constantinople was fundamentally fractured as urban long-term resident Armenians who had not been subjected to the massacres and exile confronted an influx of traumatized Armenian villagers who had survived them and been deported to the city. She explains that once in the city, surveillance by “communal mechanisms and state institutions” subjected Armenians to life within a “panopticon.”Footnote 70

Following the 1923 foundation of the Republic of Turkey, efforts to homogenize the citizenry coincided with top-down campaigns aimed at uniting the population around Turkish nationalism. This entailed new coercive assimilatory policies against ethnoreligious minorities, even as the nation's elite claimed for the new Turkish nation the success of cultural products produced in a formerly plural society. In 1940, the Turkish newspaper Son Posta published a front-page feature entitled “It seems we've been exporting jazz band cymbals to the entire world!” (quickly leading with the line, “It turns out we have no idea what important things we have exported!”) This self-congratulatory article celebrates the demand for “Turkish cymbals” in Western nations such as Germany and France, comparing their fame to that of Turkish tobacco and Kütahya porcelain.Footnote 71 Buried halfway through the article is the mention of “the Jewish citizen” Yako Toledo, who organizes the international export of cymbals; as a passing thought, the article notes, “however, the maker is Armenian,” referring to the brand “K. Zilciyan” (the Turkish spelling of Zildjian) without referencing any of the craftspeople.Footnote 72 Accompanied by a caricature of a Black jazz drummer (drawn with exaggerated physical features and an inaccurately portrayed drum kit), the article proclaims, “We will certainly have customers in America. It is thought that jazz was born there. If the noisiness of America's music were to come to one's attention, one would easily understand how many ‘cymbals’ they need.”Footnote 73 Here it is worth noting the parallels between the Turkish newspaper's exoticized representation of “noisy” American jazz music (and assertions of the cymbal's suitability for the genre) and the aforementioned European observers’ descriptions of the “noisiness” of Ottoman mehter music featuring cymbals in the seventeenth century. Ironically, the latter part of the article primarily covers exporter Yako Toledo's disdain for the cymbals produced by the American-based A. Zildjian Company (“in America our imitator has arisen”), whose collaborations with jazz drummers resulted in the cymbal's central role in and re-design for jazz music (Figure 7).Footnote 74

Figure 7. “It seems we've been exporting jazz band cymbals to the entire world!” Son Posta, March 6, 1940. Provided by İstanbul Üniversitesi Gazeteden Tarihe Bakış Projesi.

Despite efforts to construe the global demand for cymbals as an accomplishment of the Turkish nation, oppressive policies intended to Turkify the population stifled members of ethnoreligious minorities, including those at the helm of the Istanbul-based K. Zildjian operation. The CUP had largely eradicated non-Muslim groups from the Anatolian regions of Turkey between 1913 and 1923, and significant minority populations (Greeks, Armenians, and Jews) remained only in Istanbul.Footnote 75 During World War II, the Turkish government implemented the Varlık Vergisi (Capital Tax), disproportionately and swiftly imposing steep taxes on non-Muslims. Compared to the 4.94 percent tax imposed on Muslim Turks, the tax imposed on Greeks was 156 percent, Jews 179 percent, and Armenians 232 percent; furthermore, the new law seized and liquidated the assets of debtors and exiled them to forced labor in Eastern Anatolia if they could not pay in cash within days.Footnote 76 As historian Sait Çetinoğlu has described, the ruling elite deliberately designed these discriminatory measures to “destroy the economic and cultural base of these minorities, loot their properties and means of livelihood, and, at the same time, ‘turkify’ the economy of Turkey.”Footnote 77 A 1943 New York Times article describes tax assessments on ethnoreligious minorities as “confiscatory figures” that seemed “intended to drive non-Moslems out of business and thus solve once and for all the problem of minority control of much of Turkey's commercial life.”Footnote 78 Despite the feature article reveling in the success of Turkish cymbals abroad just a few years prior, the K. Zildjian Company (run by Mikhail Zilçan) was subjected to the same harsh assessment under the Varlık Vergisi. A public notice in the newspaper Tasvir-i Efkâr broadcast the outcome: “‘The lathe, machinery, complete iron and wooden boilers, tools and equipment for the production of cymbals, and 17 band cymbals and other band equipage’ at the business located at 45-47 İnekçi Street in Sancaktar Hayrettin neighborhood were confiscated from Vahan and Mikail Zilciyan, who did not pay their tax debts.”Footnote 79, Footnote 80 An article featuring an extensive interview with Robert Zildjian also notes, “In 1941, Kerope Zilcan narrowly escaped being killed in a political massacre”; although the article does not provide further detail on Kerope's experience, it is notable that 1941 was the year in which the Turkish government conscripted non-Muslim subjects to heavy labor under extremely adverse conditions in work battalions, an event known as the Twenty Classes (Yirmi Kur'a Nafıa Askerleri).Footnote 81 In this period, Salomon Covo, son-in-law of the aforementioned Yako Toledo, prevented the Istanbul company's insolvency by purchasing it, serving as owner and general manager.Footnote 82

Although sources on his experiences in this period are limited, one can imagine that these difficulties took a toll on Mikhail and his family. He traveled to the U.S. in 1955 to testify on behalf of Gretsch in a lawsuit brought by the A. Zildjian Company. There, he successfully asserted that the cymbals the two firms produced were not identical products and thus should maintain the right to the K. Zildjian trademark. That year also marked a large-scale pogrom in Istanbul that destroyed and looted thousands of Greek, Jewish, and Armenian homes and businesses, a government-organized mob that sought to intimidate, disenfranchise, and displace minorities. The tax burden to which the Turkey-based Zilçans were subjected, whether they were threatened with forced labor, and the extent to which the pogrom affected their neighborhoods and livelihoods are unclear. Nonetheless, despite national and international celebration of the cymbal, the climate in Istanbul was undoubtedly hostile and the challenges from the American A. Zildjian operation stymying.

In a 1976 New York Times article, Mikhail reminisced about the success he had enjoyed in the 1930s and attributed current difficulties turning profits to “the rising costs of men and metal,” lamenting, “Everywhere I go in Europe or the states, the Zildjian family is known. People think we are very rich, they don't know that we are penniless.”Footnote 83 The A. Zildjian Company's 1977 acquisition of the K. Zildjian Company marked the end of its operations in Turkey. Mikhail's death the following year mobilized his former apprentices Agop Tomurcuk and Mehmet Tamdeğer to start their own cymbal workshop from the remnants left after the acquisition and his passing. Agop's son Arman explained that his father had clandestinely observed the secret alloy formula while working for Mikhail: “First, my father tried to buy the business, but when Zilcan refused, he felt he was entitled to get that formula. And since that night, we have kept it as our family secret.”Footnote 84

Although the tens of thousands of Armenians who migrated to the United States in the early 1900s left behind the Ottoman millet system and oppression they faced under the CUP and its Republican successors, once in the U.S., they often faced contestations of their racial identity and right to American citizenship. The Christian faith of most Armenians may have somewhat eased their entry into the U.S. Extensive foreign media coverage decried the persecution of “Christian” Armenians in Turkey (including 145 articles in 1915 by the New York Times alone), and editorials discussed American and European ideological and hegemonic incentives to support a self-governed Armenian state.Footnote 85 In a volume of editorials published by the Armenian National Union of America in 1919, American ex-ambassador to Germany James Gerard indicates that these incentives included fears of militant pan-Islamism and “pan-Turanian peril” if the former Ottoman empire were to spread through all of Central Asia. He also states the U.S.'s duties to a fellow Christian nation and the potential for Armenia to become the “outpost of American civilization in the east” as reasons to offer support (Figure 8).Footnote 86

Figure 8. A 1932 fundraising campaign poster for the American Committee for Relief in the Near East. Library of Congress.

Moreover, efforts to represent Armenians’ race as “European” rather than “Oriental” (including in court testimony by anthropologists such as Franz Boas) facilitated assimilation.Footnote 87 Legal rulings, including the 1909 Halladjian court decision in Massachusetts (the first Armenian naturalization case) and the 1925 dismissal of the United States vs Tatos Osgihan Cartozian naturalization challenge, helped give Armenian immigrants legal standing to claim status as “free white person[s]”; per the judge in the latter case, Armenians were empowered to assert their ability to “amalgamate readily with the white races, including the white people of the United States.”Footnote 88 These rulings were supported through testimony that often entrenched white supremacist ideology, framing Armenian white identity in contrast to that of racialized Japanese, Chinese, and Black subjects as well as “Turkish invaders.”Footnote 89 Unlike with Armenian communities in or from the Middle East, where articulating an Armenian ethnic identity and transmitting Armenian language skills were more compatible with life in a multicultural host country, “the assimilation of Armenian immigrants in the United States proceed[ed] hand in hand with changes in the nature of [their] Armenianness.”Footnote 90 Gender theorist Janice Okoomian describes Armenians in this period as navigating “racial borderlands,” in which achieving “secure” white status meant downplaying “Oriental” differences and articulations of suffering in the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 91

The Zildjian cymbal narrative does not dwell on the challenges of negotiating an Armenian diasporic identity in America; the official line underscores that Avedis III had opened a candy factory and married an American woman (Sally, the “Yankee” mother of the “two American sons”), but agreed to take over the cymbal business if he could continue the operation in America.Footnote 92 The story of the cymbal's entrance into the drum kits of legends such as Max Roach tends to highlight Avedis’ relationships with jazz drummers rather than the difficulties of being Armenian in America, much less American ideological and hegemonic aspirations in Turkey or the ways in which Armenian “whiteness” was established in contrast to other ethnoracialized minority populations in the United States. On the current website, the Zildjian Company timeline marker for the year 1936 attributes Avedis’ cymbal innovations to the fact that he was “quick to embrace the talented African-American musicians who are leading the jazz movement. Having been discriminated during his own childhood as an Armenian living in Turkey, Avedis vows there will be no place for discrimination at the Zildjian Company.”Footnote 93

Avedis III's story is one of successful assimilation and the accompanying rewards of the American dream. Emphasized is his mastery of five languages and close collaborations with famed drummers of the day.Footnote 94 A Newsweek feature in 1939 highlighting Avedis’ ingenuity with the craft and ability to build a business despite the economic challenges of the Great Depression further cements progress and emergence as a capitalist subject as distinguishing features of the Zildjian legacy.Footnote 95

Pressure from forces in the entertainment industry and broader geopolitical forces may have also had bearing on the Zildjians’ ability to assert their own heritage as well as the cymbals’ heritage as overtly Armenian. The Turkish ambassador to the U.S. between 1934 and 1944 Münir Ertegün sought to suppress anti-Turkish sentiment and vehemently denied Armenian genocide. In 1935, Ertegün contacted U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull to protest MGM's production of a film rendition of the Forty Days of Musa Dagh, threatening Turkish backlash if the studio made a movie of the popular novel about the Armenian genocide. MGM cancelled the film production, and in 1947 Ertegün's sons Ahmet and Nesuhi founded Atlantic Records, which would become one of the most successful and powerful record labels (particularly for jazz) in the U.S.Footnote 96 Given that some of the Zildjians’ most influential musical collaborators recorded with Atlantic Records, it is plausible that the Ertegün family's influence and the pro-Turkish lobby in the U.S. may have led the Zildjians to emphasize a shared Ottoman past rather than risk controversy by highlighting the Zildjian cymbal-makers’ Ottoman–Armenian legacy. Until 2019, the U.S. government actively denied recognizing the systematic massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire as a genocide due to the desire to maintain favorable relations with the Turkish government, a critical NATO ally, which also sponsored campaigns to discredit evidence that such events had ever occurred. Although Avedis gave up Ottoman citizenship with his naturalization in the U.S. in 1916, emphasizing the cymbal's historical Ottoman connections has remained an essential part of the company's marketing strategy; similarly, Armenian–American newspapers to this day still claim the Zildjians as Armenian success stories.Footnote 97 Maintaining the Zildjian cymbal's historical ties thus entails condoning a romanticized view of a multicultural and ethnoreligiously plural society in the Ottoman Empire while sidestepping direct confrontation of Ottoman and Turkish national policies that contributed to coercion and violence against Armenians, directly affecting the trajectory of the Zildjians and their cymbals.

Conclusion

Let us momentarily return to the Zildjian factory in Norwell, Massachusetts: The Ottoman mehter mannequin is displayed steps away from a replica of Ringo Starr's drum kit, a hallway away from the master (human) lathers working alongside robotic hammering machines. One encounters in the Zildjian factory's vat of alloy a material embodiment of Henri Bergson's durée: Creation, production, reproduction, and modification exist in one flow of time, rendering the distinction of “present” versus “past” inconsequent and immaterial.Footnote 98 In the alloy, predecessors, successors, contemporaries, and consociates meet as one, and timespaces and the genealogies that they support (familial and metallurgic alike) emerge in the symbolic divisions of cymbalic production. Just as the Zildjian cymbal can at once sonically index Ottoman mehter bands, symphonic orchestras, jazz and rock bands, and many other ensemble formats and genres, so too can it resound multiple, seemingly disparate, timespaces in its materiality and narrativization. The materiality of the Zildjian cymbal, the lineage of its alloy, also offers glimpses into the construction of familial lineage and identity for the human Zildjian descendants (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Gravestone of Puzant Zildjian in Mt. Auburn Cemetery, Massachusetts. Photo by author.

The gravestone of Puzant Zildjian, younger brother of Avedis III who helped to start the first U.S. factory, lies in Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 13 miles north of the first American Zildjian factory in Quincy, Massachusetts. It bears not only the names of him and his wife Arpine, but also a cymbal mounted into the stone—a fitting reminder of how the instrument, in its narrativization and material creation, has served to animate and sustain a sense of kinship across a longer Zildjian family lineage.

In examining a well-hammered Zildjian cymbal, we can glimpse how its human creators derive value from the history ascribed to a material object, capitalizing upon and transforming the various cultural meanings associated with it. As an instrument that gathers and resounds the meanings inscribed upon it, the cymbal serves a vital role in human constructions of self and belonging in relation to notions of past, present, and future timespaces. Reflecting on its present ubiquity entails considering the many meanings it has acquired through its manifestations in Ottoman mehter ensembles, European orchestras, American jazz bands, and now countless popular music genres around the world. Once largely regarded as noisy, exotic, and even terrifying, over the past four centuries, the sound of the cymbal has become assimilated as a standard musical tone color in orchestras and bands; tracing these processes can also illuminate the assimilatory pressures confronted by individual members of the Zildjian family, and more broadly many Armenians, in the Ottoman Empire, Republic of Turkey, and United States. The intertwined mobilities of instrument and maker also indicate the complex shifts and conflations of the Zildjians’ identity: As Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, Armenians contradistinctive to the (former) Ottoman Empire, Ottoman and/or Turkish for advertising purposes (whether for the historical, national, or exoticized element), “white enough” to be American citizens and yet grappling with ethnoracialization as Other in ways that facilitated affinity with Black musicians and musical styles.

It is my hope that this exploration invites further contemplation about how Eurocentric models of the modern nation-state are reified through commodifying “emplacing objects” such as the cymbal and the various circumscribed meanings ascribed to them. The assimilatory pressures exerted by modern-nation states have frequently required that subjects suppress and/or curate expressions of difference within dominant ideologies around “heritage,” “history,” and “culture,” subordinating discordant expressions of identity contained within such categories to narratives of modernity, progress, and success. I suggest we engage with musical instruments as essential mediators of histories of cultural and musicological development as well as constructions of human identity and relationship, glimpsing how such objects may both reify and unsettle our epistemologies and the institutions of modern life.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Kay Kaufman Shelemay and Kate van Orden for organizing the visit to the Zildjian factory in Norwell that sparked this exploration. I appreciate Anne Shreffler, Martin Brody, Christopher Hasty, Jonathan Gomez, and David Forrest for their encouragement and willingness to discuss the arguments presented in earlier drafts of this article. I benefited from presenting previous versions of this work to the participants at the 2019 conference “Entangled Encounters: Antiquity and Modernity in Armenian Studies” at Harvard University and the 2021 Society for Ethnomusicology meeting. I thank Katie Callum for her editorial feedback before the submission process. The thoughtful feedback of this journal's editors and two anonymous reviewers indelibly strengthened this article. Finally, I extend tremendous thanks to my institutional sponsors over the past years, including Koç University's Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, the British Institute at Ankara, the Fulbright-Hays DDRA Grant program, and the Orient-Institut Istanbul, whose inspiring scholarly communities and financial support have enabled me to pursue my research.

Competing interests

None.

Audrey M. Wozniak is an ethnomusicologist who writes about discursive and material constructions of kinship and the state in urban diasporic contexts, particularly those of Turkey and China. Her current monograph project centers the notion of discipline within historical and contemporary patterns of musical labor in Turkey and its diaspora. She is also an accomplished violinist performing Western and Turkish classical music and experienced facilitator of multimedia artistic programming. She seeks to cultivate cross-cultural exploration and curiosity, creating experiences that invite the audience to engage with culture, sound, and space in unanticipated ways. For more, please visit www.audreywoz.com.