Introduction

In archaeology, the story of the past is largely told through the experiences of men. There have been noticeably fewer explorations of the wider spectrum of gendered identities and ideologies that undoubtedly existed during the human past. This is perhaps not surprising given that many inequalities based on sex, sexual preference or sexual identity persist to the present day. Our versions of the past reflect the context in which archaeological knowledge is produced: a patriarchal society in which (white) men are privileged above others tends to write a past based on the supremacy of males in highly stratified cultures, mirroring their present. More surprising is that this situation persists more than 30 years after the first feminist critiques of archaeology (Conkey & Spector Reference Conkey and Spector1984; Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1991). Does this general silence about gender within the discipline of archaeology represent a backlash against feminism? Is it that feminist perspectives to the past are merely unpopular today, or are they viewed as too much of a challenge to the status quo? In a time of global feminist activism, encapsulated by movements such as ‘#MeToo’ and ‘TimesUp’, ‘Everyday Sexism Project’, ‘Repealthe8th’ and ‘Musawah’, this absence cannot reflect a disinterested audience. Rather, it demonstrates that archaeology is behind the times and needs to respond to contemporary global and intersectional feminist voices. This article represents a renewed call for explicit challenges to continuing androcentrism within archaeology. It reviews the evidence for gender disparity in the authorship of archaeological publications. The impact of this inequality is explored through the lens of later medieval archaeology in Britain and Ireland (the period AD 1066–1400 is discussed here), before providing a feminist critique of castle studies.

Gender inequality and the construction of archaeological knowledge

The gender imbalance in academia has been discussed thoroughly (see Harley Reference Harley2003: 377–92; European Commission 2008; Van den Brink & Benschop Reference Van den Brink and Benschop2012: 71–92). In archaeology, this imbalance manifests in senior roles within academia and professional practice (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2014: 1–9). How does such gender imbalance within the discipline affect the construction of knowledge and, in particular, the representation of women and the interrogation of gender in the past (Conkey & Gero Reference Conkey and Gero1997; Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1999)? This question is addressed here by analysing ‘The Oxford Handbooks of Archaeology’ series as an index for gender imbalance in authorship. These volumes are commissioned as ‘go-to’ guides for students and professionals that make, shape and capture the state-of-the-art in the discipline. Ten handbooks from a wide chronological, thematic and geographic range are considered: Archaeology (Gosden et al. Reference Gosden, Cunliffe and Joyce2009), Anglo-Saxon archaeology (Hinton et al. Reference Hinton, Crawford and Hamerow2011), Ritual and religion (Insoll Reference Insoll2011), North American archaeology (Pauketat Reference Pauketat2012), African archaeology (Mitchell & Lane Reference Mitchell and Lane2013), European Bronze Age (Fokkens & Harding Reference Fokkens and Harding2013), Death and burial (Stutz & Tarlow Reference Stutz and Tarlow2013), Neolithic Europe (Fowler et al. Reference Fowler, Harding and Hofmann2015), Later medieval archaeology (Gerrard & Gutiérrez Reference Gerrard and Gutiérrez2018) and Childhood (Crawford et al. Reference Crawford, Hadley and Shepherd2018) (Figure 1). For balance, potential gender disparity in authorship is also assessed within three journals of medieval archaeology published in France, Britain and Italy (Figure 2). For multi-authored papers, all authors were included in the analysis.

Figure 1. Gender balance in a selection of Oxford handbooks of archaeology (figure by the author).

Figure 2. Breakdown of gender balance in three medieval archaeological journals: Reti Medievali, Archéologie médiévale and Medieval Archaeology 2014–2017 (figure by the author).

Men dominate the authorship in eight of the ten handbooks (Figure 1). Based on their public profiles, the authors presented as overwhelmingly white (over 95 per cent) in all publications. The gender disparity of the handbooks only somewhat contrasts with the three medieval archaeology journals (Figure 2). In the Oxford handbook of later medieval archaeology (Gerrard & Gutiérrez Reference Gerrard and Gutiérrez2018), for example, there are twice as many male authors as female authors. In the section on ‘Power and display’, all five chapters are by men. In contrast, six of the nine papers in the ‘Growing up and growing old’ section are by women (66 per cent). The message for medieval archaeologists is that women = nurture/care, and men = power. In Ritual and religion there were only 15 female authors in contrast with 53 male. Women outnumber male authors in only two of the handbooks: Childhood and Death and burial. These comparisons are revealing in relation to contemporary gender roles: today, women are largely responsible for the primary care of children and elderly people. World religions—organised or otherwise—still exclude women from roles as ritual specialists. While power and display are explicit themes in many of the Oxford handbooks, gender is not. The discussions therefore only account for an assumed and projected heteronormative past, and anything beyond the ‘normative’ is unexplored, including Queer or LGBTQ+ perspectives.

It could be argued optimistically that the discipline has ‘mainstreamed’ gender or, in other words, that gender has been embedded in wider interpretation and no longer requires explicit discussion. This, of course, is precisely the problem: a particular gendered ideology is implicit throughout many archaeological texts—that of the lives and practices of white, able-bodied heterosexual men. This means that many archaeologists, not just men, write about what is effectively the modern status quo. Not all men, of course, write exclusively about other men, or use masculinist perspectives; nor are all people with different gendered identities, including women, interested in writing about females, disenfranchised or underrepresented people. Yet it remains the case that women and all those who fall outside the ‘mainstream’ category of the white, heteronormative male are noticeably absent from the narrative—both as topics for discussion and as authors.

The question is: does this matter? Do we need more diversity in authorship in order to see more diversity in the past? I argue that this is imperative. Embracing different and diverse voices would enhance our understanding of both the past and the present. It is unlikely that people would openly oppose this sentiment, but the evidence suggests that we still fall short of achieving these aims. We must ask then: who is responsible for ensuring that we have diverse representation? The answer is, of course, all of us. Together, we must strive to include others. We must all be reflective and conscious of what choices we make in relation to our archaeological practice; who is represented, as well as underrepresented, and who is affected. There is, however, a special onus on those ‘gatekeepers’ who control or influence archaeological discourse to be as inclusive as possible (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012). This means actively addressing these disparities. It may also mean asking difficult questions or refusing to participate in an event or publication that lacks fair representation, while recognising that, despite best efforts, such editorial balance can be difficult to achieve (Gerrard & Gutiérrez pers. comm.).

While this article focuses on gender inequality and feminism, the wider “matrix of domination”, which reinforces structural inequalities especially with regard to racism, must be acknowledged (Collins Reference Collins2000: 227). It is noted that the majority of authors were white males, and where women are included, they are also predominately white. It is hypocritical to argue for the greater inclusion of (white) women while ignoring the structural inequalities that result in the exclusion of people of colour—especially women of colour, indigenous people and trans and gender-non-conforming people. We must be careful not to forget (or deny) the inherently patriarchal structure of academia and the colonial origins of archaeology as a discipline (Gosden Reference Gosden2004; Kim Reference Kim2017). A broad-brush analysis of race, class, sexual orientation and ethnicity, however, is not attempted here, as these require detailed attention in their own right (Franklin Reference Franklin2001). Racism, for example, exists and must be challenged in our discourses. A positive shift to address this—particularly within the disciplines of medieval history and literature—is the emerging field of ‘Global Middle Ages’, which foregrounds studies of ‘Race and racism’ and decolonises the Middle Ages as a Eurocentric idea (Heng Reference Heng2011; Kim Reference Kim2017; Montón-Subías & Hernando Reference Montón-Subías and Hernando2018).

Gendered archaeologies

The twenty-first century has witnessed an increasing acceptance that gender is fluid, non-binary and non-normative (Gosling Reference Gosling2018). Gender differences are socially constructed, historically contingent and changing. For millennia, people have (re)negotiated context-specific gendered roles and other aspects of their identities involving ethnicity, sexuality and age. Awareness of this is evidenced by examples of gendered archaeologies (e.g. Tringham Reference Tringham, Gero and Conkey1991; Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1999; Sørenson Reference Sørensen2000; Brück Reference Brück2009), as well as archaeologies of sexuality (Voss Reference Voss2008). Yet there remains a resistance (or an apathy) towards more broadly incorporating the ways that scholars have created, assembled and reinforced gender roles into archaeological accounts of the past. It is telling that there is no ‘Oxford handbook of gender archaeology’, and studies that offer insights into what women and other gendered identities did in the past are still rare (Dowson Reference Dowson2000; Voss Reference Voss2000, Reference Voss2008; Ghisleni et al. Reference Ghisleni, Jordan and Fioccoprile2016). Problematically, gender-inclusive archaeologies often consist of ‘filling in the gaps’ of past narratives (Figure 3); this approach, however, fails to critique the gendered assumptions on which pre-existing interpretations were based (see Tringham Reference Tringham, Gero and Conkey1991: 94). Also, the projection into the past of gendered ideologies based upon heteronormative family units is rarely challenged, although there are some exceptions; these include that of Reeder (Reference Reeder2000), who advanced the (contested) idea of a homosexual relationship to explain depictions of two Egyptian elite males within their shared tomb (c. 2300 BC). This raises important questions: are scholars afraid that studies of gender, women or those who existed outside mainstream ‘normative’ society are not ‘acceptable’ within the Establishment? Can we attribute the paucity of gender research to anxieties about what is valued by the Academy? Are we reifying power dynamics in our scholarship that are more revealing of the sexual politics of our world than those of the past (Conboy et al. Reference Conboy, Medina and Standboy1997: 2)?

Figure 3. ‘Filling in the gaps’: an outdated approach (image by the author).

Gender and medieval archaeology in Britain and Ireland

The paucity of research into gendered identities in the medieval past is difficult to comprehend. It seems that the closer we come to the white-washed, heteronormative and patriarchal ‘modern world’ (of Europe), the harder it is to imagine an alternative past. In the context of medieval European archaeology, this may be because the medieval past can seem so familiar that it is easy to assume that we already know it intimately. We know people's names, the places they lived, the words they wrote down, the plays they watched, the songs they sang, the fields they worked, and we have some of the things that they used, loved and cared about. Furthermore, modern religions still retain and perform certain aspects of their cosmology.

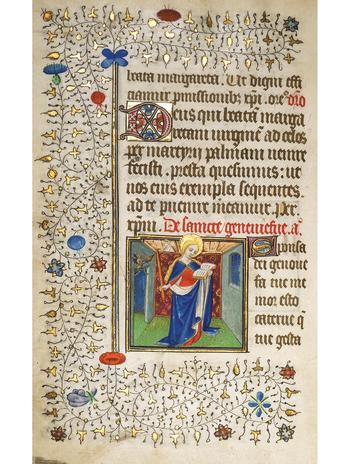

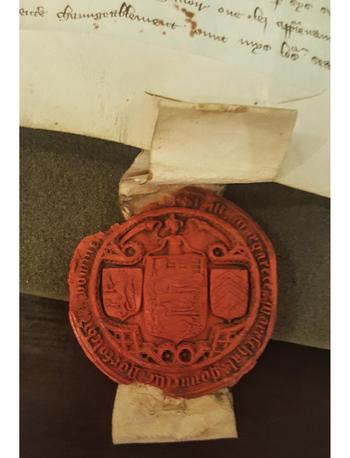

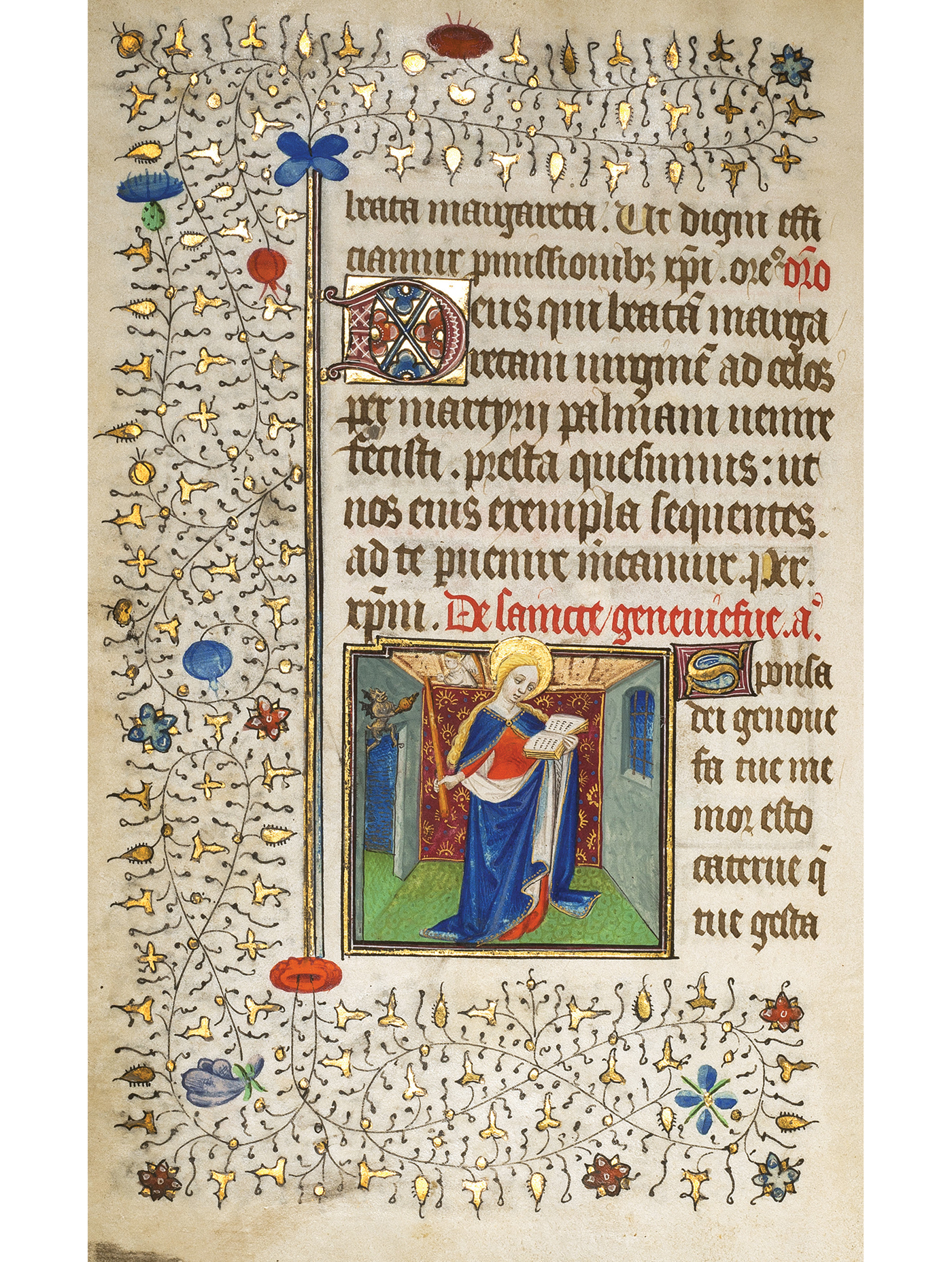

The material culture of late medieval Britain and Ireland is incredibly rich. Funerary monuments and effigies offer insights into mortuary practices and representations of the dead, while architecture provides a material context embodied with gender relations and domestic tensions (Figure 4). Literary texts and images are a rich source for representations of rituals surrounding belief and devotion, but also of daily life and the gendered aspects of book ownership (Figure 5). The design, production, use and decommissioning of objects, such as ceramics and metalwork, further inform our understandings (Figure 6–7). Interweaving these ‘data’ with our investigations of social relations demonstrates how the archaeological record—in the widest interpretation of that term—can be used to tell less fragmentary stories about the gendered lives of medieval people.

Figure 4. Chepstow Castle in Wales (photograph by the author).

Figure 5. Detail of St Genevieve in MS 2087 Book of Hours (courtesy of University of Reading Special Collections).

Figure 6. Seal of Margaret Mareschall, Countess of Northfolch and Lady Segrave (photograph by the author, courtesy of Charlotte Berry, Magdalen College, Oxford).

Figure 7. Exeter puzzle jug (courtesy of Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Exeter City Council).

Given the richness of our sources, it is curious that inclusive studies are not more common in medieval archaeology. Why are other disciplines—particularly medieval history and literature—capable of exploring individual agency, social relations and the lived experiences of medieval men and women? (e.g. Woolgar Reference Woolgar1999; Gee Reference Gee2002; Nolan Reference Nolan2009; Martin Reference Martin2012; Moss Reference Moss and Martin2012; Jasperse Reference Jasperse2017; Delman Reference Delman2019). Key themes addressed in these cognate disciplines are sponsorship (patronage) and religious devotion among elite women, while non-elites, such as washerwomen, maidservants, midwives and prostitutes, feature somewhat less (Rawcliffe Reference Rawcliffe2009; Müller Reference Müller, Beattie and Stevens2013). These disciplines, however, still show an explicit awareness of the complex ways in which medieval people constructed their identities. This has resulted in innovative explorations of sexuality, the body, gendered identities, queerness and, of course, women and feminist activism (e.g. Green Reference Green2008; L'Estrange Reference L'Estrange2008; French Reference French2013; Maude Reference Maude2014; Moss Reference Moss2018).

The absence of these approaches is keenly felt in the study of later medieval archaeology, which remains shaped by the predominance of androcentric (male-biased) perspectives. Gilchrist (Reference Gilchrist1991) first examined inequality in the practice and discourse of archaeology in Britain, later demonstrating how a gendered archaeological approach could reveal a more complex story of the past (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1994, Reference Gilchrist1999, Reference Gilchrist2012). Beyond Gilchrist's scholarship and work by Johnson (Reference Johnson2002), Giles (Reference Giles2007, Reference Giles, Giles and Kristiansen2014) and Graves (Reference Graves2007), there has been an apparent resistance to the types of social approaches, such as embodiment, materiality or phenomenology, that have been employed in prehistoric studies (e.g. Cooney Reference Cooney2000; Brück Reference Brück2009; Carlin Reference Carlin2018). Except in rare instances (e.g. Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2012; Robb & Harris Reference Robb and Harris2013), archaeologies of the life course and the body have largely been neglected. Studies that include Queer theory (Dowson Reference Dowson2000; Voss Reference Voss2000; Ghisleni et al. Reference Ghisleni, Jordan and Fioccoprile2016) are absent. Gendered interpretations that explore LGBTQ+ perspectives are non-existent and very rare across archaeology more generally. While some publications do foreground ‘gender’—a malapropos for the study of women—these largely tell stories of women in the male world (Standley Reference Standley2008, Reference Standley2016; Hicks Reference Hicks2009; Richardson Reference Richardson2012; Wiekart Reference Wiekart and Stull2014; Collins Reference Collins, Campbell, Fitzpatrick and Horning2018). With few exceptions, this perceived disinterest in gender contrasts with early medieval, Anglo-Saxon and Viking studies, in which these subjects are explored to some extent (e.g. Lucy Reference Lucy, Hinton, Crawford and Hamerow2011; Poole Reference Poole2013; O'Sullivan Reference O'Sullivan2015). Is this indifference a reflection of unconscious bias in scholarly research or a conscious effort to reinforce a particular status quo? Gendered differences are manifest in both past and present, and the absence of attention to the performance of gender is therefore startling.

Gender and castle studies: the missing link

Understanding the issues in relation to gender within castle studies requires some reflection; while this article does not provide a full historiography of castle studies, brief commentary is necessary (Barry Reference Barry2008; O'Conor Reference O'Conor2008; Creighton Reference Creighton2009; Hansson Reference Hansson, Gilchrist and Reynolds2009). As with archaeology more generally, castle studies requires an interdisciplinary approach to explore the past in full; the application of necessary methods, however, has been limited. Nonetheless, the field has undergone a profound transformation over the past three decades, moving away from military frameworks (Allen Brown et al. Reference Allen Brown, Colvin and Taylor Brown1963) and embracing deeper explorations of space and place. New approaches have emerged that focus on the symbolic meaning of castles and explore what these buildings might have meant to the medieval person. The emphasis has shifted from simply recounting detailed architectural descriptions towards integrated, interpretative approaches that view the spatial arrangement of buildings as a reflection and enactment of cultural ideologies (e.g. Coulson Reference Coulson1976; Heslop Reference Heslop1991; Fairclough Reference Fairclough1992; Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1999; Marshall Reference Marshall, Meirion-Jones, Impey and Jones2002; Richardson Reference Richardson2003; Mol Reference Mol2011; O'Keeffe Reference O'Keeffe2015). Subsequently, a new wave of castle studies operating at a landscape-scale have looked beyond the masonry buildings to propose that the castle was only one part of a seigneurial package. This complex comprised many features, including dovecotes, villages, earthworks, water features and farms, through which to display, enhance and manage lordly economic, political and cultural authority (Hansson Reference Hansson2006; Creighton & Liddiard Reference Creighton and Liddiard2008). This shift in approach represents a reaction against long-standing essentialist arguments based on binary oppositional understandings: military vs domestic, and defence vs display. The debates that ensued resulted in a more critical discourse and an acknowledgement that castles served multiple roles (Johnson Reference Johnson2002; Speight Reference Speight2004; Liddiard Reference Liddiard2005; Creighton & Liddiard Reference Creighton and Liddiard2008).

While these methodologies were at one time beneficial, they are now problematic. Landscape studies are based on macro-scale approaches that concentrate on displays of power, economic production, ecological exploitation and diet (Liddiard Reference Liddiard2005; Creighton Reference Creighton2009; O'Conor et al. Reference O'Conor, Naessens and Sherlock2012; Swallow Reference Swallow2014; Beglane Reference Beglane2015). They rarely, however, address the micro-scale of daily life, or other issues such as gender, sexuality, emotion and the life course. Castle studies has not yet fully embraced social archaeology. While spatial approaches have been a key focus for archaeologists and architectural historians for two decades, they have not brought us any closer to understanding how people occupied these spaces. Interpretations of the spatial arrangement of buildings remain heavily influenced by perspectives of masculine rationality (Boys Reference Boys and Ainley1998). Buildings are thought to have a ‘grammar’ to be ‘read’ (Johnson Reference Johnson2002). Medieval use of space is still characterised and debated through dualistic binaries: public vs private, sacred vs profane, military vs domestic and male vs female, thus reinforcing oppositional understandings of man vs women, self vs other, subject vs object. This culture of dualisms stems from androcentric thinking, in which man is the beneficiary. In other words, the male ‘subject’ is viewed as active, rational and powerful, the female ‘object’ is emotional, passive and can be exploited.

While we can demonstrate that medieval society was highly stratified and that social space and interaction were regulated (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1999; Hannson Reference Hansson, Gilchrist and Reynolds2009), there remains an onus on the gender scholar to prove that matters are anything other than male. Buildings may be thought of as active agents, but often only in terms of masculine power, wealth and status. Women, in this model, are determined as passive, secluded ‘objects’, excluded from the ‘location of power’, which is a male or masculine space (Johnson Reference Johnson2002). If this view is accepted, then one could safely assume that this exclusion had a physical manifestation in the form of a particular set of rooms from which women were excluded or secluded within. Yet, confusingly, the idea of ‘female space’ in the castle is persistently resisted, despite their obvious and tangible presence. Goodall (Reference Goodall2011: 21) contends that women and children were entirely absent from castles, and that medieval elite households were celibate and male. Even if this were true, why are homosocial behaviours (Moss Reference Moss2018), performances of masculinities or potential male homosexual relations not explored in this scenario?

Our current view of the later medieval period typically comprises buildings, objects and landscapes often detached from each other. Discussions of castles have not yet combined people, places and things together within their historical context. Architecture has a much richer role to play in archaeological interpretation than as a passive reflection of human behaviour, or as a binary didactic instrument, containing or transmitting social cues. Architecture must be examined in terms of lived experience and as material culture. While some scholars do concentrate on the latter, it is often analysed in a typological or scientific manner—especially pottery—and not contextualised spatially within the castle (e.g. Creighton & Wright Reference Creighton and Wright2016). People are mostly discussed in terms of power, as patrons or ruling lords; in other words, elite males or females who operated as such. Taken together, these traits reveal the discipline's lack of enthusiasm to engage in meaningful discourses about biographies, life cycles, social practices, beliefs and identities.

One key issue is that castle studies remains a male-dominated field. Despite the ‘new wave’ of such studies moving beyond militarism, it still typically reproduces male-centred interpretations epitomised by a focus on political power or status. Studies that focus on women often endeavour to insert the female into ‘traditionally’ male activities, rather than creating a narrative of the female experience of living in the medieval world (e.g. Richardson Reference Richardson2012). This is problematic, as it results in ‘male qualities’ being prioritised in analyses of social activities. There is no doubt that castles and associated activities have been long viewed as male, where metonyms for masculinity comprised weapons, armour and horses (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1999: 121). Generally, castle scholars no longer explicitly depict the castle as an aggressively male-only world of sweat and testosterone; the current, insidious ‘gender-blindness’ within castle studies, however, ensures the preservation of this now implicit ideology. Women, and those who were (or are?) not accepted as part of mainstream society, are absent(ed)—figuratively and literally. It seems that the discipline is focused on maintaining a particular status quo in the present by projecting ‘known’ gender constructs and roles onto the past, thereby ignoring other possibilities (Conkey & Spector Reference Conkey and Spector1984).

Ideally, castle studies would foreground human-centred stories that emphasise the real complexities of everyday life, where—as today—the world is experienced through the spectrum of human emotions. My current Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship, ‘HeRstory’, aims to achieve this by focusing on 12 castles as case studies across Ireland, Britain and France. Crucially, it integrates people, places and things, and asks new questions of the archaeological evidence, such as: how was gender constructed and mediated in relation to the medieval castle? What was it like to be a person, other than an elite male, living in the medieval castle? What material and social practices shaped the world of the castle? The inclusion of gendered interpretations is a fundamental issue not just for castle studies, but also for medieval archaeology and archaeology more generally, where many scholars still take a singular view of the past: that of able-bodied, heterosexual men of power—in other words, the modern ‘masculine’ status quo.

Conclusion

Archaeology reinforces or projects a real and mythologised patriarchal hierarchy within its scholarship. Consistently endorsing male authors, male perspectives and male stories, it perpetuates the idea of ‘male activities’ as superior. This affects not only our understanding of the past, but also maintains the patriarchal status quo in the present. If a male-oriented narrative is dominant and represented in scholarship, and it is embedded within a patriarchal academy that reinforces androcentrism, then archaeological (or other) evidence that speaks to the contrary will continue to be overlooked or disregarded. Our discourses must create multi-vocal narratives that reveal the social complexities and diversity of the world. In an era of global feminist activism, it is no longer acceptable to portray the past through one master narrative that consistently ignores the lives and experiences of othered people, especially women and those who do not conform to the heteronormative or white Eurocentric ‘ideal’. This means moving away from accepting or assuming binary and heteronormative notions of the past.

Our scholarship needs to stop identifying gender—especially in attempting to make women visible—and to acknowledge that gender is already there. Rather than “add women and stir” (Tringham Reference Tringham, Gero and Conkey1991: 94), we need to weave a new story, reimagining all the threads of various elements of past identities and social relations, and the wide spectrum of gendered identities, to form a rich tapestry of the past and the present that constructs it (Figure 8). If we remain complacent to the current gender (and racial) disparity, we are complicit in reinforcing the unequal status quo, and we fail to reach a large part of the potential audience for archaeology—those who feel disenfranchised by patriarchal, heteronormative or colonial narratives.

Figure 8. Imagining the past as a textile: ‘Entwined’ (image courtesy of Jill Sharpe).

While we now accept that our ways of being in the present inform how we view and interpret the past, many scholars are unable (or unwilling?) to discuss their personal motivations for choosing a particular interpretative approach. The lack of reflection given to the author's personal perspective in many archaeological studies is a core issue in how structural inequalities endure, including the perpetuation of patriarchal approaches. Discrimination today based on sex, gender or sexual orientation is intrinsically linked to the paucity of research on gender in the past. To combat this, we must all demonstrate who we are and why we ‘do’ our studies in our own particular way. To paraphrase Virginia Woolf, this means changing and adapting, re-arranging our rooms (physical, literal and digital) to encourage other people to take up and redefine that space in order to enable a diverse, multi-vocal archaeology.

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 74606. Thanks to Neil Carlin, Daisy Black and Aleks Pluskowski for commenting on this article. A very special thanks to Roberta Gilchrist for assistance and constructive comments. This article adds to the conversation she initiated in Antiquity in 1991.