Looking forward, looking back

![]() One day, hundreds of years in the future, archaeologists digging an early twenty-first-century rubbish dump will come across a sharp stratigraphic interface between a thick deposit of disposable paper cups and a layer of vinyl gloves and plastic aprons. What events might have caused such an abrupt cessation of coffee consumption and a new concern for personal protection? Looking further afield, the archaeologists might observe other contemporaneous changes such as increased mortality and reduced levels of CO2 in the atmosphere. Was this rapid and global-scale change the result of political collapse, warfare—or pandemic?

One day, hundreds of years in the future, archaeologists digging an early twenty-first-century rubbish dump will come across a sharp stratigraphic interface between a thick deposit of disposable paper cups and a layer of vinyl gloves and plastic aprons. What events might have caused such an abrupt cessation of coffee consumption and a new concern for personal protection? Looking further afield, the archaeologists might observe other contemporaneous changes such as increased mortality and reduced levels of CO2 in the atmosphere. Was this rapid and global-scale change the result of political collapse, warfare—or pandemic?

Over the first months of 2020, the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, has transformed our lives and lexicons: self-isolation, social distancing, shielding and curve flattening, key workers and home workers, lockdowns, shelter-in-place orders and social bubbles—the new normal. At the time of writing (early May), more than a quarter of a million lives have been lost and large parts of the world's population remain under various restrictions on their freedom to travel, work and socialise. While some countries have ‘passed the peak’ and have begun to reopen shops, factories and schools, others have yet to experience the full force of the virus. Everywhere there is great uncertainty about the myriad implications of COVID-19 for the future.

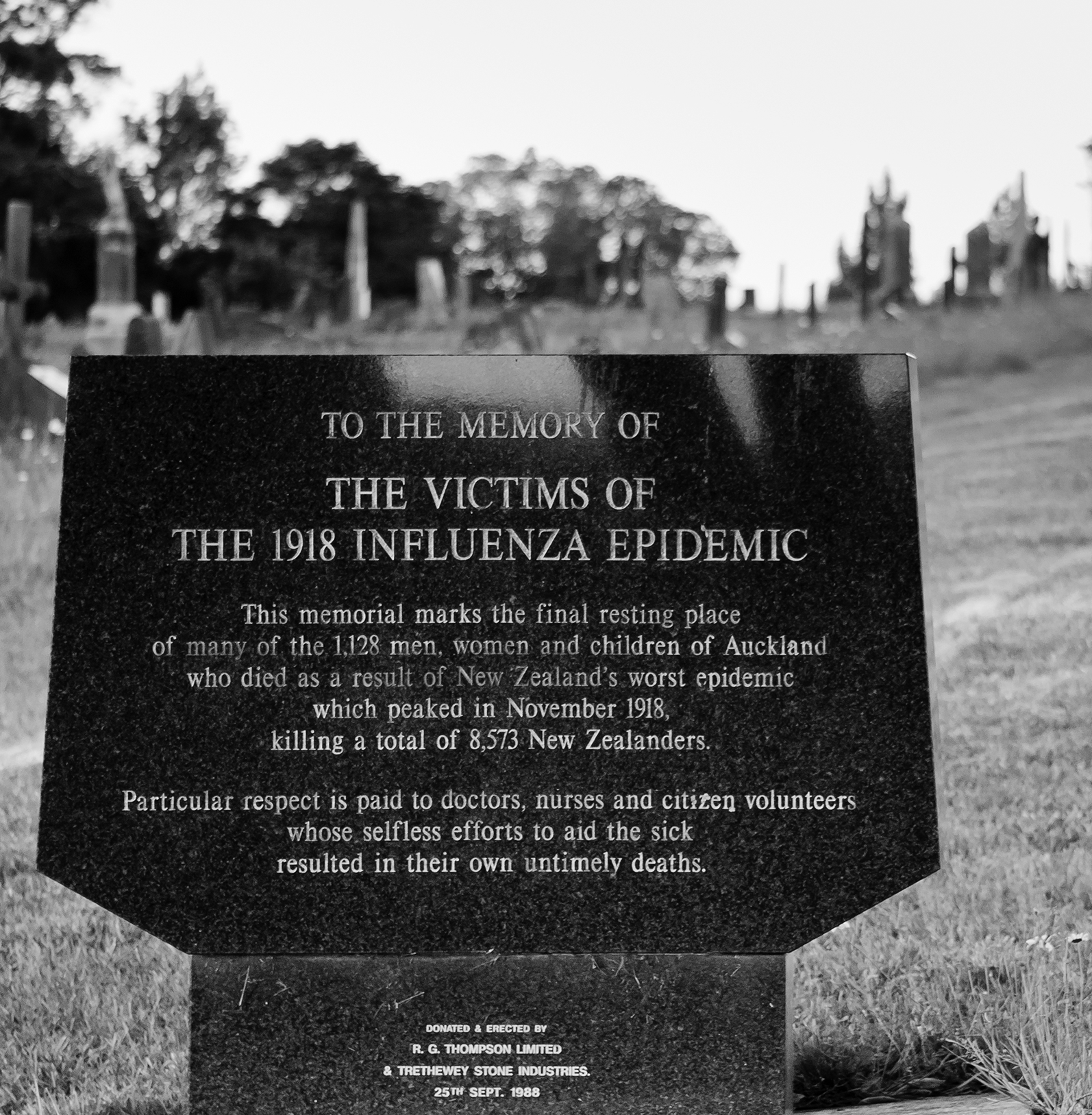

As a society, we could seek insight into our predicament by looking back to historical outbreaks of disease and their consequences. The most obvious example is the 1918 flu pandemic, which struck in the aftermath of the First World War, ultimately claiming many more lives than the war itself. Our collective memorialisation of pandemic and war, however, are very different. The many monuments to fallen soldiers contrast sharply with the sparse commemoration of those lost to disease; high-profile events to mark the centenary of the armistice far exceed those recalling one of the most deadly pandemics of the twentieth century (Figure 1). Hence, although ‘plague columns’ were once a common sight in European cities, today our collective memories concentrate on moments of national origins, greatness or sacrifice. For example, the events planned—although now scaled back—to mark the 400 years since the Mayflower landed in Massachusetts, are unmatched by similar events recalling historical outbreaks of disease. Will the bicentenary of the second cholera pandemic of 1826–1837 be as visibly marked as this year's 250th anniversary of Cook's arrival in New Zealand and Australia? The victims, and the lessons, of previous pandemics are not at the fore of our collective consciousness.

Figure 1. A plaque erected to commemorate some of the victims of the 1918 flu pandemic in Auckland, New Zealand. The plaque reads: This memorial marks the final resting place of many of the 1,128 men, women and children of Auckland who died as a result of New Zealand's worst epidemic which peaked in November 1918, killing a total of 8,573 New Zealanders (image source: 1918 Influenza Epidemic Site; author: russellstreet; cropped from original, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en ).

With politicians and the public understandably anxious about the present and concerned for the future, archaeologists worrying about how we maintain our study of the past might easily be dismissed as myopic. Yet now is precisely the time to seek a long historical perspective on the evidence for earlier pandemics and other societal shocks, and to evaluate both the immediate and enduring effects for social organisation, economic inequality and health.

Such thinking is embedded in archaeology's ‘grand challenges’, a series of questions intended to prioritise archaeological research on the interaction of past human and natural systems, and to encourage other disciplines to make use of our insights.Footnote 1 Of the 25 questions defined back in 2014, two assume particular resonance for our current predicament: ‘what factors drive health and well-being in prehistory and history’; and ‘can we characterise social collapse or decline in a way that is applicable across cultures, and are there any warning signals that collapse or severe decline is near?’. Archaeologists have long studied communicable diseases, such as tuberculosis, and their evolution due to human activities such as animal domestication, warfare, trade and environmental exploitation. Did we see the ‘warning signals’? Arguably, yes. Were we able to communicate these concerns in ways that informed political debate, contingency planning and social policy? Arguably, no, although as a discipline we have no more failed than have the medics and epidemiologists whose warnings of a pandemic much worse than SARS or MERS fell on deaf political ears. In the years ahead, we will need to rethink how we communicate the knowledge and understanding gained through our study of the past to inform political leaders and policy-makers of the consequences of actions—or inaction—in the face of humanity's grand challenges.

As the restrictions on social and economic activities begin to lift, we will need to rethink almost every other aspect of our profession as well. Conferences offer a case study of the disruption to our usual ways of working, of the systemic problems exposed by the virus and of the potential for alternative ways of organising ourselves. Over the past few years, the numbers of international conferences, workshops and meetings have grown. These gatherings serve a critical role in communicating results and discussing ideas, in networking and in advancing knowledge; they are also about sociality and experiencing new places. Huge meetings such as the SAA and EAA are major annual events bringing together archaeologists dispersed across entire continents and beyond; many smaller, specialist and periodic conferences fill out the calendar. Now, nearly all of these meetings have been cancelled, postponed until 2021, or are seeking to ‘go digital’. The disappointment and disruption is significant, but we should take the opportunity to reflect on our conference habit. For while each meeting can justify its own existence, how many, collectively, do we really need? Not only do these meetings have an enormous aggregate carbon footprint, but also their prohibitive costs exclude many colleagues, especially younger researchers and those from less well-funded institutions or regions. While these are not new observations, COVID-19 provides the exogenous shock that makes it both more essential and easier to change direction.

There are various potential models. Recently, for example, a group of ecologists has advanced the concept of the ABCD conference, intended to address the same range of concerns that challenge archaeologists.Footnote 2 (ABCD stands for All continents, Balanced gender, low Carbon transport and Diverse backgrounds.) The format mixes in-person and pre-recorded talks with live-streamed presentations to encourage a wider range of participants while reducing the environmental impact. The venues for physical gatherings rotate to different parts of the world, allowing regional scholars to gather in person, while video-conferencing facilitates inclusive international participation. Such formats will require experimentation, but the speed with which we have turned to online teaching, virtual viva examinations and Zoom meetings suggests that, when required, we can rapidly innovate our practices. Inevitably, such formats will fail to replicate in full the ‘real-world’ conference experience—the serendipitous conversations, the local cuisine, the annual party—but the gains to be made regarding our social and ecological responsibilities are tangible and achievable.

Global perspectives

![]() The ongoing social, economic and political shifts catalysed by COVID-19 are so rapid and profound that any current thinking about the pandemic's impact on the discipline is inevitably preliminary. Nonetheless, as we begin to grapple with the changes that will play out over the coming months and years, there is value in assembling a snapshot of the fears and hopes that characterise the present moment. We have therefore invited colleagues from around the world to offer their initial thoughts. The aim is to gather a range of voices representing different regions and archaeological sectors, acknowledging that this can only incompletely reflect the scale and varied impact of the pandemic. We start with the President of the World Archaeological Congress (WAC), Koji Mizoguchi of Kyushu University, Japan.

The ongoing social, economic and political shifts catalysed by COVID-19 are so rapid and profound that any current thinking about the pandemic's impact on the discipline is inevitably preliminary. Nonetheless, as we begin to grapple with the changes that will play out over the coming months and years, there is value in assembling a snapshot of the fears and hopes that characterise the present moment. We have therefore invited colleagues from around the world to offer their initial thoughts. The aim is to gather a range of voices representing different regions and archaeological sectors, acknowledging that this can only incompletely reflect the scale and varied impact of the pandemic. We start with the President of the World Archaeological Congress (WAC), Koji Mizoguchi of Kyushu University, Japan.

A virus that transcends animal and human boundaries, that spreads across all socio-cultural, economic, political and ethnic boundaries. A virus that divides and closes down human society. A virus that spreads through the infrastructural systems of globalisation and destroys global solidarity. A virus that is a contradiction and therefore embodies and exposes the contradictions of the contemporary world. Confronted by this absolute, even transcendental, threat, what should we do to maintain solidarity? How can we halt the spread of the virus while continuing to live and work together?

The COVID-19 pandemic challenges archaeologists and heritage specialists in ways that vary by country and region and that impact differently according to age, gender, ethnicity and income. Yet collectively, our discipline faces an existential challenge: is archaeology necessary in these difficult times? And if so, for whom and with what purpose? We can claim to learn lessons from the past, including insights into human successes and failures in response to earlier destructive episodes. We could therefore say that archaeology is both necessary and valuable for the identification of ideas about how to respond to the pandemic and to maintain the well-being of society. Inevitably, the pictures that emerge from archaeological investigations are complicated, messy, and rarely provide us with clear answers. Such pictures nonetheless provide multi-faceted ideas for how each of us can change our behaviours and the consequences that might follow.

The problem is that, in these difficult times, this line of thinking—this belief—derived from our daily experience of dealing with complex, long-term archaeological phenomena, might be criticised, rejected or even laughed at. One reason is that, from long before the pandemic, increasing numbers among us have promoted simplistic cause-and-effect explanations and short-term answers. Ironically, this attraction to uncomplicated causation and easy solutions, both in our personal lives and throughout global society, results from the same globalisation and hyper-capitalism that have facilitated the very spread of the virus.

The long-term welfare of societies and communities is sustained by the sense of ontological security shared by their members. The health of a civil society depends upon mutual tolerance and support among its citizens: they must feel that they know who they are and what to expect from and do for their compatriots. These senses derive from a shared grasp of the necessity of maintaining the sociality that historically has enabled individuals and communities to survive and thrive despite the messiness and complexity of reality. This is what the archaeological study of the past can teach us or, at least, what we as archaeologists feel and believe through our daily experiences.

Confronted with COVID-19, the challenge is whether as archaeologists and heritage specialists we can convincingly share our experiences and beliefs with the general public, who ultimately support our operation financially. We must collaborate with the general public, here and now, to provide long-term perspectives on the pandemic and its consequences, which will prepare us for the sustained, highly complicated and messy struggle ahead. More than ever, these archaeologies need also to bring us joy, a sense of belonging and of connectedness across all of the boundaries that divide us at this moment of crisis.

WAC aims to bring together archaeologists from around the world to promote responsible and inclusive practice. Among many other activities, this aim is supported by meetings of the Congress every four years. The next meeting, WAC-9, scheduled to convene in Prague in July, has inevitably been postponed, one of the many conferences, field seasons and lab projects that have been cancelled or postponed over the past few months. Such activities are integral to archaeological research, so what has been the impact of the pandemic on research-intensive institutions? As Director of the Department of Archaeology at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History based in Jena, Germany, Nicole Boivin oversees a large community of researchers with a global portfolio of partnerships and projects, with particular strengths in the archaeology of Asia, Africa and South America.

Like many research organisations around the world, the Department of Archaeology at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History has been severely impacted by COVID-19. Most of our projects involve either lab-based research or overseas fieldwork, and all such research has come to a halt. We are unlikely to be able to return to the field anytime soon, and many planned conferences, exchanges and meetings are indefinitely on hold. Furthermore, our staff consists primarily of early career researchers who will be especially hard hit by the impending recession, facing what is increasingly anticipated to be a brutal job market as universities begin to cancel or postpone recruitment. It is thus all the more remarkable to see colleagues focused on supporting each other and finding solutions. Early career researchers have pushed on with reconfigured projects, and shown extraordinary resilience. This is critical because as we face the dual challenges of a devastating pandemic and continued anthropogenic climate warming, doing and promoting science is more important than ever.

Resilience and creativity will be critical in the coming years. Like our students reimagining their projects, we should use COVID-19 as an opportunity to reimagine our discipline and our priorities. This includes recognising that we need to become better at communicating science to the public, and making the past relevant to the challenges we face today. It might also mean using the experience of our rapid and enforced shift to online exchange to reimagine how we interact and build international collaborations, as well as how we could potentially provide greater flexibility to working parents. We might also reconsider the necessity for so much travel and the huge conferences that fly people across the world for a few days and leave a devastating ecological footprint. Times of crisis bring great challenges but also opportunities to reassess, re-evaluate and rethink the world that we inhabit, participate in and actively create. In the coming years we will face many challenges in archaeology, and in academia more broadly, but perhaps the greatest of these will be to avoid going back to ‘business as usual’ when COVID-19 eventually recedes.

The impact of COVID-19 on the comparatively well-funded and globally connected institutions of Europe, East Asia and North America is likely to be severe. What does the situation look like from the perspective of smaller organisations in other parts of the world? Shanti Pappu and Kumar Akhilesh of the Sharma Centre for Heritage Education send a note from India.

Amidst the familiar sounds of excavation—the hum of conversation, the swish of brushes, the excited cries of visiting children—COVID-19 was a term as distant in time and space as the people who fashioned the stone tools buried beneath our feet. Now, within weeks, we are in lockdown, a world of social distancing alien to the Indian lifestyle. The dust from the trench is replaced by an invisible enemy; scarves morph into masks. Confronted with fear, death and hunger, the lives of long-forgotten hominins and their tales of past resilience seem of little relevance.

Our fieldwork plans for the year are put on hold. Instead, we turn to social media, seeking free video-conferencing tools to reach out to collaborators around the world. We develop a new online discussion group, ‘Down Ancient Trails’. For some of us, the switch to a virtual world is effortless, for others it is a struggle to adapt to new technology and behavioural rules—not unlike the experiences of our Palaeolithic ancestors.

Over the years, we have developed a stoic acceptance of being quarantined, not by a virus, but by a paucity of funds that largely excludes us from participation in international conferences. We live on the fringes of the global discourses and networks dominated by the West, relegated to communicating through the written word. Will COVID-19 overturn the rules of the game for archaeologists in countries such as India? With traditional conference models temporarily shelved, will online exchange multiply previously silent voices and diverse views? In this virtual world is there potential to tilt the balance of the existing cliques of power and privilege? Far removed from these thoughts of research, we also temporarily suspend the renovation of our children's museum and our onsite public outreach activities and student workshops. We shift instead from teaching through hands-on ‘mock’ trenches and stone knapping to modes of instruction governed by the touch of the mouse and viewed on a screen, whilst sadly aware that few of the children with whom we usually work have access to these virtual worlds.

By the time this note is published, novelty will have become routine as we adapt to new realities, combining high science with our supposedly characteristic skills of Indian ‘Jugaad’, endlessly pulling through by relying on local innovation. In this deadly present, echoing a John Wyndham novel, ancient behavioural patterns confront new circumstances evolving into patterns that will become a focus of study for future archaeologists. Footnote 3

Despite all of the uncertainty and tragedy brought by COVID-19, it is striking that our contributors also find hope in the opportunity to reimagine a future where the practice of archaeology is more ecologically sustainable, more equitable and, as our next correspondent argues, more useful. Shadreck Chirikure of the University of Cape Town and winner of the 2019 Antiquity Prize reflects on the potential impact and implications of COVID-19 on the future of African archaeology.

The insidious COVID-19 pandemic has been so devastating that it has placed most of the world under lockdown. Africa, the world's second largest continent, appears to be the last to experience the devastation. It is too early to predict how severe the full impact of the virus will be in different African countries, each with its own set of challenges, such as hunger, poverty and inequality. Against this background, how will African governments respond to the localised and globalised events triggered by COVID-19? This question is essential because under ‘normal’ circumstances, the low prioritisation of archaeology and heritage makes it legitimate to ponder the situation that may emerge in the aftermath of the pandemic. Depending on how one looks at it, the crisis offers a unique opportunity for archaeologists to combine curiosity-driven research with investigations that address the challenges facing Africa in areas such as diet and nutrition, social inequality and the evolution of diseases and local cures. Coronavirus or no coronavirus, research pursuing the past for its own sake is unhelpful both to the discipline and to African communities and policymakers alike. These broad foci of research are essential for correcting the view that archaeology and heritage exist only as fodder for tourism and to provide the materials for moulding national identities. For if African governments continue with business as usual and do not provide financial support for archaeology, it is likely that foreign funding will continue to sustain research in Africa, with agendas developed outside the continent. In that case, research is likely to continue for the short to medium term, but without African priorities as the guiding principles. Either way, a business-as-usual approach is unlikely to produce meaningful results. It will be essential to balance curiosity-driven investigations with solutions-based research so that archaeologists can address some of the exceptional challenges affecting African society, such as climate change, hunger, disease and (un)employment. In this way, the discipline might be shifted from the periphery to the centre of decision-making.

In many countries around the world, the majority of archaeological fieldwork undertaken is rescue- or developer-led assessment and excavation. With strict physical-distancing regulations in place, much of this activity has been halted temporarily, although it will likely be among the first sectors of the economy to return to work. Yet, with significant recession on the horizon, longer-term construction plans will be scaled back, evoking memories of the impact of the 2008 financial crash on commercial archaeology in countries such as Spain and Ireland. Dominique Garcia, the Head of Inrap, gives an update on the impact of COVID-19 on the work of France's Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives.

Between 17 March and 11 May 2020, some 200 Inrap archaeology projects employing 2000 archaeologists were suspended and all of the Institute's 50 research centres temporarily closed. Unfinished excavations were physically secured and placed under video surveillance to protect both the archaeological remains and the data already collected: field recordings, surveys and photographs. Despite the COVID-19 shutdown, however, we have been keen to ensure that our research activity continues wherever possible.

In France, preventive excavation is linked by definition to the construction and public works sector, with which we have maintained close relationships during this period of suspended fieldwork. For our part, we have sought to prioritise the most urgent situations in order to allow the construction companies affected to catch up on their schedules. As archaeological assessments must be examined by local prefectures before authorisation for the release of land to builders can be granted, we have continued to process data, to write up reports and to submit texts to publishers. In addition to working with industry, we also disseminate archaeological results to researchers and to the public. In the context of the physical restrictions imposed by COVID-19 regulations, Inrap has developed an open-access policy making freely available its entire documentary collection of thousands of site reports to allow students and researchers to continue their work via the Dolia digital library. Moreover, we have maintained our core educational aim through the provision of free cultural and educational digital resources (available via inrap.fr), which have been in great demand from schoolchildren and teachers.

Over the past three months, the suspension of many of our activities has led to a loss of income amounting to tens of millions of euros. This financial hit poses a threat to our mission to research, protect and educate. The resumption of operational activities (11 May), however, was only possible when health guarantees for our field staff could be met and when the French government was once again able to exercise its scientific and technical control in the field.

Finally, we return to Antiquity's backyard in the north of England and the site of Vindolanda, a fort on the northern frontier of the Roman Empire. Over the past 50 years, the site has developed into both a research hub and an important regional heritage attraction. What are the effects of the global pandemic on the many independent organisations that own and manage archaeological sites, museums and other heritage attractions and the wider communities and economies of which they are part? Andrew Birley, Director of Excavations, explains.

The impact of COVID-19 on the Vindolanda Trust, its research agenda and economic viability has been severe. The Trust raises most of its income through visitors to our sites, supporting research, excavation, conservation and the care of our Nationally Designated Museum collection. Based on 2019 figures, the Vindolanda Trust will lose nearly half a million pounds towards those aims and objectives between April and June this year. These are catastrophic losses.

To protect jobs and the future viability of the organisation, researchers, archaeological and conservation teams, and customer service staff have been furloughed. Nonetheless, our obligations to protect the sites, museums and collections remain, as do the costs. As elsewhere, excavations, research and scientific conferences have been cancelled through to June, and plans through to the end of the year remain under threat. Our vital Vindolanda volunteer community is currently unable to come in person to the site, but we have sought to engage with them virtually and to maintain their active involvement.

Going forward the Trust assesses the greatest threat will be the nature and length of the recovery. An anticipated economic depression, reduced travel, partial reopening of different sectors and lower incomes will all have a profound negative impact on our research and conservation work. We expect the loss of partners in the academic and commercial archaeology worlds, reduced opportunities for funding applications, and a sustained downturn in visitors stretching into 2021 and 2022. Vindolanda is tightly networked into a mutually supportive framework of local businesses and providers who rely on each other's success. Without the survival of pubs, cafes, B&Bs and hotels there will be fewer facilities to attract and service the visitors who support the regional economy of which we are part. Post-COVID-19 will not be business as usual. But we are confident that we will survive, even if we cannot at the moment predict what shape we will be in this time next year.

Thanks to all the contributors for offering their insights at this early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic and for venturing their thoughts on how we might reimagine our discipline over the years to come. Whether you are still under lockdown, Zoom-ing into an online class or digging in a trench at an appropriate distance from your co-workers, stay safe!