For the musicologist Hermann von der Pfordten, writing in 1917, it was proof of German cultural superiority that young soldiers sang “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles” as they charged the enemy near the village of Langemarck, Belgium, in autumn 1914, meeting inevitable death. Singing, he explained, was engrained in German character—including in the trenches and on the battlefield. This patriotism, everywhere apparent in his book on “the historical and national foundations of German music,”Footnote 1 was how von der Pfordten, age sixty, helped the war effort. From a prominent Munich family and on the faculty of the Ludwig Maximilian University, von der Pfordten sought to bolster morale while his younger cousin Theodor was first lieutenant on the western front—until a minor injury qualified the jurist to become commander of a prisoner of war camp where Russians were allegedly abused. Von der Pfordten's book has long since been forgotten and so too its author—although Theodor, who went on to plan the 1923 Munich Putsch with Hitler, would be memorialized in the Third Reich as one of the sixteen Nazis shot dead in the fracas.

The dissemination of the report about German soldiers at Langemarck is remarkable as a study of failed war propaganda (its claim of victory implausible to most) that flourished as myth. The military action was catastrophic—a last German effort in the first battle of Ypres by four reserve corps, newly formed from young recruits, to dislodge the British by advancing across open ground. It left ten thousand dead and wounded, and the British held Ypres throughout the war, although their own later offensives around Ypres proved equally disastrous. Originally a tale of youthful bravery, Langemarck became more useful as a moving story of patriotic sacrifice. In a war where so many men died on remote battlefields without proper family rites, the Langemarck narrative provided a redeeming vision of an appalling and fruitless massacre. Singing gave death on the battlefield a face—as well as aestheticizing the gruesome modernity of war.

From the first reports of the battle on November 11, 1914, the singing at Langemarck sparked the literary imagination. Yet the adaptations in poetry and fiction, traced here in the initial years of dissemination, cannot be read as a reliable testimony about the lives of those who participated in, or witnessed, the war. The massive outpouring of poetry and songs, especially early in World War I, which reach beyond traditional bourgeois literary circles, creates the illusion of a literary hegemony, with soldiers writing and consuming poetry in communion with those at home. This vision of soldiery is, however, absent in letters written on the front. The transmission of the Langemarck report shows a relatively narrow audience, not just in the war years but as the right wing embraced the myth during the Weimar Republic.

The Langemarck myth has fascinated historians, most notably the World War II veteran Karl Unruh and German-Jewish émigré George Mosse.Footnote 2 Yet the significance of the soldiers singing and what they sang has been all but ignored. If the intended purpose of the Langemarck report is difficult to reconstruct, the many paths of transmission make clear that one consequence of the myth, if not its purpose, was to solidify the choice of the Deutschlandlied as the new republic's national anthem in 1922. This article proposes to examine how the song became endowed with an almost sacral significance for those who may have died singing it, those for whom that constructed memory sanctified it, and for those who instrumentalized their memory.

“Deutschland, Deutschland über alles,” unlike other national anthems, was musically attributable to a major composer, Joseph Haydn. Originating in his 1797 hymn “Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser,” the theme inspired Haydn to compose a variation set that same year to supply the slow movement for his string quartet, Op. 76, no. 3. Adaptations to the text allowed Haydn's Kaiser hymn to remain in use in the Austro-Hungarian empire until 1918 and again during Austria's first republic from 1922 to 1938. This usage did not stop Hoffmann von Fallersleben in 1841 from crafting a poem that matched the melody exactly, “Das Lied der Deutschen,” as he envisioned a nation spanning the German-speaking states “from the Maas to the Memel, and from the Etsch to the Belt” (Meuse and Niemen, the waterways on the west and east, Adige and Danish Straits, on the south and north).

The story of Langemarck exemplified not just German bravery, for von der Pfordten and his generation, but the German patrimony of a profound musicality and associated morality. Dismissive of “foreign arias,” von der Pfordten invoked the metaphor of the “healthy home cooking [by] the German girl and the German woman” to describe the musical probity of what was sung by men in the tavern, students at a cafe, and youth while hiking. Von der Pfordten circled back to the Langemarck anecdote later in his book, within a discussion of Haydn. The inestimable value of this melody was that “art music and folk music are in essence one and the same.” Haydn achieved the simplicity and beauty of a “true folk song,” and yet the theme has such artistic integrity that could support a variation set. Imbuing the melody with a quasi-spiritual meaning, at the liminal space between life and death, von der Pfordten recounted how Haydn, ill and unable to compose at the end of his life, would sit at the keyboard playing that same melody. Yet as a scholar, von der Pfordten felt compelled to add, “Whether it is literally true that he sought emotional consolation need not concern us; it is clear that the afterworld was revealed to him in unexpected power.” This slippage from fiction into myth is telling: readers were to accept as undisputed that Haydn confronted death more meaningfully in playing the tune. Von der Pfordten concludes with a broad historical sweep:

This melody did not remain the Austrian Kaiser Hymn but rather became the Song of Songs of German identity. With it, we recognize our national sanctity. With this song, our youth encountered death. With it, our heroes showed their sacrifice. With it, we who remain at home show our eternal faith in the fatherland. With this melody, we sing our “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles.”Footnote 3

The Langemarck story served to enhance the popularity of the Deutschlandlied at a time when the official national anthem, “Heil dir im Siegerkranz,” came under attack. The melody of the latter, taken from the British anthem “God Save the King,” discredited the song during the war, even though the lyrics were originally written by a Schleswig German for the Danish king, Christian VII, then sovereign over the German duchy. The cult that developed around Langemarck during the war and early postwar years helped to bolster the contested claim of “Deutschland, Deutschland, über alles” as national anthem in 1922. Without seeking to establish an etiology for the Langemarck myth, this article introduces several pertinent sources in the press, any one of which could have emboldened High Command to release the brief report on November 11, 1914.

The most brash proposal for a new national anthem came from Friedrich von Gagern, later admired by Hitler as a populist writer of antisemitic leanings. German patriotism came easily to von Gagern when war broke. Unable to afford his familial Mokrice Castle in Croatia (its contents and buildings gradually sold during World War I) and alienated from the Catholic Church (he converted to Protestantism in 1910 order to marry a divorcée, Countess Mathilde Kospoth), von Gagern found himself widowed with a toddler and a baby in March 1914. Vacating his deceased wife's familial castle in Briese, Silesia (Brzezinka, which would become the site of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp), von Gagern moved to Leipzig, a Protestant musical bastion, to study with the renowned organist of Bach's Thomaskirche, Karl Straube. It is here where the Austrian author and now organ student, too old to enlist (age thirty-two) but witnessing the mass of men who did, took up his pen with a patriotic fervor.

How could a Volk that produced the “heroes of music”—Beethoven, Mozart, Schumann, and Wagner—not create its own national anthem, von Gagern asked. “For our Kaiser, for our fatherland, for Germany and for Germans, we want to have another song.” Railing against the inauthenticity of “Heil dir im Siegerkranz,” von Gagern felt certain that military success would generate a new national anthem. Longtime editor of a hunting magazine and aspiring nature writer, von Gagern hatched an organic metaphor to explain how a national anthem gains legitimacy: “It must emerge from the people, as the tree grows from the earth; it must have roots in the people; and its sap must be the spirit of the people.” In his metonym, the German national anthem would defeat those of France, Britain, and Russia:

Perhaps from Germany's rapid and shining victories a true and pure German Kaiser song will arise. It will arise in defeating the Marseillaise and Rule Britannia, and the late Aleksey L'vov's chorale—which is far too good for Russia. The weapons will write and compose it. And the Volk, in deep gratitude, and reborn in need and blood and courage, will sing it before the towering instances of its praise.Footnote 4

The aestheticization of song was in keeping with von Gagern's aristocratic literary circles (Count Anton Alexander von Auersperg was his great uncle). Yet in the wake of the so-called “August experience”—an enthusiasm for war that was as much contrived in the press as self-generated in the crowds of large cities—von Gagern found a wider audience for his patriotic excesses. Buoyed by the German victories on the western front on August 21–30, von Gagern wrote this article for the Berlin populist newspaper Der Tag on September 4, 1914. Within days, the German advance lost its momentum in the First Battle of the Marne, and eventually von Gagern lost interest in producing war propaganda.Footnote 5

Music, Morale, and War Reporting

As the confidence in a swift victory dissolved, many questioned the very reason for war, which spawned a range of defensive arguments from both individuals and the state. Managing public opinion became more important than it had been for any past war. Newspapers needed to include details that fostered trust, yet headlines remained positive, and bad news from the front was suppressed or delayed. These tactics did not, however, succeed in allaying concerns about the war. A striking example is the Berliner Tageblatt on Monday, August 24, 1914. Headlines announcing “victory”—all allegedly Germany's—were well positioned, with three on the front page and one on the second page, whereas articles on the wounded and on welfare organizations were relegated to the third and fourth pages. (The last page, mostly advertising, included sports and a report on the US economy.) It was not difficult to see through the veil of optimism. The headline across the front page, “The German Army at Lunéville—A Victory of the Crown Prince,” was explained under another headline, lower center: “Victory at Longwy under the German Crown Prince,” which presented the official report that on Sunday morning, Crown Prince Wilhelm had “victoriously” pushed back the French at Longwy, and the Bavarian Crown Prince, leading the army that had been “victorious in Lothringen,” pressed the defeated French back to Lunéville. (This fleeting success would be overturned on August 24–26 at the Battle of the Trouée de Charmes, which caused the Germans to move back to their positions before the victory at the Battle of Lorraine, which began on August 14.) The reporting was accurate, yet the “victories” were successful initiatives made possible by the disorderly retreat of the French, not full-fledged battles.

The misinformation came from the account of the third “victory,” positioned in the lower right-hand corner of the front page. “The Russian Offensive” was the main headline, with descriptive headlines below: “The Russian Attempts to Break Through—The Victory at Gumbinnen [Gusev, Russia]—The Russian Forces Advancing.” The false claim of a German victory on August 20 at Gumbinnen originated in the official report of August 22, in which the eight thousand prisoners taken were said to be Russian, when in reality they were German. German troops were ordered to withdraw from East Prussia; the general held responsible for the debacle was replaced (Maximilian von Prittwitz), and many troops were transferred from the western front (although thanks to plans found on a dead Russian officer, Germany secured a decisive victory some ten days later in the Battle of Tannenberg). Germans back at home did not necessarily believe the rosy press. In his diary on August 23, Eduard Engel—a linguist who published detailed diaries of the war—recounted his sleepless nights and nightmares about the war even as he reproduced the daily upbeat news telegraph.Footnote 6

Writing that same day, the Berliner Tageblatt's military expert who authored most of the war reports, Major Ernest Morath, sought to mediate between the official account and the bleak reality of the eastern front, interlacing assertions of German superiority and past victories with concessions about the intensity of the Russian attacks and the vulnerability of German positions.Footnote 7 The evening edition released a detailed report from War Minister Hermann von Stein. The number of Russian captives rose to 8,500—still no reference to any German prisoners of war—and three German victories were claimed on the eastern front. Yet the larger picture was bleak, and readers were reminded of the “unexpectedly favorable” success on western front to counterbalance the news of the “encounter with the enemy on German territory” on the eastern front. The German retreat was alleged to be a precautionary move, not a sign of defeat. Acknowledging rumors to the contrary, von Stein stated in boldface, “No German army has been defeated.” In a telling formulation, he made the nondefeat seem psychological rather than tactical: “Our troops are equipped with the awareness of victory and superiority.”Footnote 8

On that same morning, the Berliner Tageblatt editors resorted to cultural programming to address the unspeakable question of when—and implicitly whether—Germany would actually be victorious. The framework was itself a type of propaganda: Leopold Hirschberg, a book collector and staff writer at a music journal, published a lengthy essay, “How Beethoven Sang of War and Victory,” marking the centenary of the German defeat of Napoleon that had proved so inspiring to the composer. Slipping into the present tense, Hirschberg suggests the utility of music to the troops: “For the soldier on the front, music is almost as important as food and sleep. Everyone who has been a soldier knows how the music of a regimental band can dispel even the worst fatigue, and how a song about the Kaiser and the fatherland pumps courage and strength into the veins.” Hirschberg admits that musically, Beethoven's war music is not among his best and yet “it is thoroughly wrong to dismiss” these works as “occasional music.” The reason for valuing this war music was its authenticity: if Beethoven's “inner self did not fully feel what happened in the grandeur of the moment, which he portrayed in these works, he never could have composed them thus.” Following a repertoire still today obscure, Hirschberg ended with a concession that a speedy victory was nearly inconceivable. In reference to a celebratory work by Beethoven, Hirschberg concluded, “Let us hope and pray that we can sing this lofty song by Beethoven not just in 1915 but even in 1914! That would be a secular commemoration more magnificent than has ever been conceived.”Footnote 9

There was historical precedent for the invigoration of German troops through music. Franz Kugler's oft-reprinted history of Frederick the Great recounted the miraculous effect of singing on German troops at Leuthen on December 5, 1757, after they had defeated the much larger Austrian forces:

In the fervor after victory, the following occurred after Friedrich ordered the grenadier battalion to Leśnica [Wrocław]. The army had set off quietly and earnestly; each walked deep in thought about the eventful, bloody day; the cold night wind spread gruesomely through the fields, which were filled with the moaning and whimpering of the wounded. Then one old grenadier began to sing the beautiful song “Nun danket alle Gott”; the brass joined, and at once the whole army, more than 25,000 men, sang as if from one mouth:

The darkness and still of the night, the horror of the battlefield—where at any point one could step on a body—gave the song a wondrous solemnity. Even the wounded forgot their pain, in order to take part in this general offering of thanks. A renewed, inner strength rejuvenated the tired soldiers. Then from all mouths resounded a loud, rising [song of] joy; and as they heard the artillery in Leśnica they hastened one after another to support their King. All enemy soldiers in Leśnica were captured.Footnote 10

If there was a specific influence on the staffer at High Command who concocted the report of soldiers in song near Langemarck, the detail is unrecoverable. If many sources suggested that reading about music on the front was comforting to those back home, one seems most pertinent. Writing in late October 1914 in the leading music journal, the gifted composer Katharina Schurzmann proposed song as a way to connect with the troops. Quoting the popular war song “Empor, mein Volk [Arise My People],” she asked, “Who does not, in the broad march rhythm…, feel transported far into enemy territory, where thousands and thousands fight for the freedom of our fatherland?… Who, in the present day, does not feel these words ringing in their heart?” She concluded with a moving allusion to soldiers who die with a song on their lips, and she insisted that the song will not die for the German people. “Born in the Great Era of the Franco-Prussian War and revived in our own present war ‘Empor mein Volk’ will resound, as almost no other song, deep in the heart.”Footnote 11

It was likely Will Vesper (a Nazi favorite) who first envisioned music as war propaganda. Vesper returned to Germany with his wife (and illustrator) after their artists’ commune in Italy was destroyed when the war broke out and, at age thirty-two, in March 1915, he volunteered for the infantry. But already in a blistering patriotism on October 8, 1914, Vesper envisioned music as an allegory for battle: “German Music” raged against the British wartime ban on German masters. Vesper in turn promised that another “music” would be forced upon the British soldiers: “A music of the Devil … a music which everyone understands, which goes from the heart to the heart, written in flaming blood-red notes.” The poet went on to threaten a musical onslaught (the guns are flutes, the cannons are double basses, and the swords are violin bows) that will turn the French and Belgians pale and make the British tremble. When the curtain rises, Vesper concluded, “our musicians will charge across the British channel!”Footnote 12 Whether it was the shrill patriotism of Vesper or the emotionalism and historical allusions of Schurzmann or some other such attempt, the receptivity of the German public to the mobilization of music was amply clear.

“Deutschland, Deutschland über alles” on the Battlefield

What really happened at Langemarck? On the morning of November 11, 1914, the news report from High Command included these details about the preceding day: “West of Langemarck, young regiments singing ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles’ broke through and captured the front line of the enemy's positions and took them. Approximately 2,000 men of the French regular infantry were taken prisoner and six machine guns captured.”Footnote 13 The engagement as reported had the mellifluous, German-sounding “Langemarck” stand in for Bixschoote, three miles due west. The report opened with the general claim that “Yesterday we made good progress in sections of the Yser River area.” The other alleged victories in Flanders included charging the town of Diksmuide (the capture of “more than 500 prisoners” and 9 machine guns) and expelling the enemy from the village of Sint-Elooi (with the capture of “approximately 1000 prisoners and 6 machine guns”).

Local movements on the western front are difficult to verify because the misinformation from High Command was widely disseminated, and official regimental histories only appeared starting in the late 1920s. It is clear that on November 11, good news was needed to offset the loss on the eastern front (Battle of the Vistula River, ending on October 31, 1914), where the German troops were reorganized and poised for the Battle of Łódź (which began on November 11). That same day newspapers published the acting Chief Admiral Paul Behncke's announcement that the SMS Emden had been abandoned at the Battle of Cocos on November 9, and that the SMS Königsberg was blockaded in German East Africa (Tanzania), two further setbacks that could be offset by an optimistic spin on the western front. The Berliner Börsen-Zeitung's front page featured a large headline, “Joyful Progress on the Western Front,” above the smaller headline, “‘Emden’ and ‘Königsberg’ lost.” The Berliner Tageblatt featured a larger central headline, “Dixmude taken in storm,” below which appeared in small font, “Heroic downfall of the ‘Emden.’” The same central headline appeared in the more populist Berliner Volks-Zeitung but without calling attention to the naval setbacks.

Historians agree that the actual conflict near Langemarck took place on October 22 (rather than shortly before November 11). Prince Albrecht von Württemberg, who led the Prussian Reserve Regiment 215, prepared for what would be massive losses—approximately 70 percent of his men over three days. Accepting the charge, he promised that “Every officer and every soldier is ready to carry out their duty down to the last breath, with old German bravery and loyalty, to give their last drop of blood for the right and sanctimony of our fatherland.”Footnote 14 The German position deteriorated rapidly. On the nights of October 26 and 29, the Belgians opened the sluices during high tide, flooding the region from the beach town of Nieuwpoort to Diksmuide, ten miles south, blocking the Germans. By November 11, Germany was six days away from discontinuing the attacks in Flanders. Winter cold hit, and, at a cost of eighty thousand men over twenty days, Germany had failed to gain access to the sea.

No contemporary sources corroborate the singing at Langemarck. It is, moreover, striking that newspapers did not comment on the spectacular statement about Langemarck—German soldiers in song who seized two thousand French prisoners. The claim of a decisive victory in trench warfare may not have convinced. Even the day before, on November 10, the official report was subdued—the attacks at Ypres proceed “slowly”; the British counterattacks, though rebuffed, were “strong.”Footnote 15 Berlin's Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung withheld the report from High Command until the following day (November 12). Instead, its November 11 evening edition relied on foreign press. Under the dark article title, “Intense Fighting in West Flanders,” news was taken from the Dutch Telegraaf, referencing the “tenacious battle at Bixchoote and Wytschaete.” Dismissing the reports of German “officers who threaten their men in battle,” the Telegraaf noted that “these people seemed driven by a contempt for death.” The Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung quoted another Dutch paper in praise of the Berlin volunteers: “One has to marvel at the German army not just for its order, discipline, and patriotism, but also its tenacity and toughness.” The author continued, “Especially the recruits educated in Berlin fought with truly fatal courage and were fired up by those comrades recruited from the best intellectual circles.”Footnote 16

Other news outlets supplied balanced accounts to offset the High Command's optimism. The Berlin branch of a women's welfare organization, Hilfsverein Deutscher Frauen, financed the publication of weekly war reports that also appeared in both English and German in the United States under the title Weltkrieg: Kriegs- und Ruhmesblätter. With a similar lede (“On November 10, material progress was made by the Germans along the Yser-Ypres canal”), the World-War went on to describe the Belgian flooding of the canals near the Yser and its tributaries, which succeeded in holding back the German advance. After conceding the enemy gains on the coast toward Lombartzyde, the World-War summarized the news from High Command's November 11 report.Footnote 17

Another reason for reporting the young soldiers in song in mid-November was proximity to the major liturgical holiday of mourning. The beautiful image of “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles” on young lips, bold in the face of death, offered succor at a time of uncertainty and bleak news to individual families. All Souls Day, the Catholic Church's commemoration, had passed (November 2), and the Lutheran Sunday of the Dead, a state holiday in Prussia since the Napoleonic Wars, was less than two weeks hence (in 1914, November 22—the last Sunday before Advent). The court chaplain in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, who published several of his wartime sermons, began by explaining,

Sunday of the Dead! Never before in our life has this holiday been so blood-soaked and so heavy with tears. Our fatherland has become a widow, a mother bowed over in pain, who with a lowered torch mourns the grave of her sons. But how? At their graves? Ah, she mostly doesn't even know the grave, where her beloved rests.

In his sermon this symbolic mother wanders everywhere, to the west, to the east, across the oceans, to find the small grave where she can kneel and cry.Footnote 18

Although propaganda about Langemarck surely originated in the High Command's attempt to conceal the November 10 defeat near Bixschoote, the basic facts were lost in the early transmission at least in military circles—in particular, the claim of victory, the high prisoner count, and even the location. Some five weeks later after the report, General Josias von Heeringen gave several interviews to the New York Times. Asked about the “bravest deed” in the war thus far, he responded, “There have been so many brave deeds that no one of them stands out pre-eminently.” The general went on, “But in the retrospect the finest thing, to my mind, was our young troops, charging for the first time in the face of a murderous fire, singing, ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles.’” The brevity of his account is peculiar, as if intimating disbelief—especially compared to the detailed story that followed (how the general's son wandered through Antwerp in search of officials to sign a surrender agreement).Footnote 19

The confusion over precisely where soldiers sang the “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles” may have begun when Paul Schreckenbach, a rural minister turned novelist, published the first volume of his illustrated history of the Great War in 1915. He republished the official November 11 report but went on to conflate two conflicts when he described the soldiers singing in Diksmuide (not Bixschoote): “The seizure of Diksmuide was the greatest German victory that November on the Western Front, and almost greater than the strategic achievement was the moral achievement. No German can read, without being moved, that the youth of their people charged into battle and death singing.” Schreckenbach went on to describe the troops—misinformed that they were mostly students—and their enormous enthusiasm.Footnote 20 His stress on the moral rather than the strategic victory would be important in years to come.

Langemarck as Literary Inspiration

Eduard Engel channeled his excitement about Langemarck into literary effusion in the war diary he began to publish in 1915. The heading for that page of his diary is “Germany's young heroic regiment.” As Reichstag stenographer for almost a half century, Engel had a predictable manner, extracting from sources available to him rather than analyzing and reflecting. But these circumstances were for Engel exceptional. After reproducing the November 11, 1914, report, Engel continued, “For centuries hereafter one will think of the young regiment at Langemarck. All of Germany quivers at this news, in a joyful cry that is smothered by tears of proud, inward joy.” Conjoining life and art, Engel reproduced the poem “Transformation” (Wandlung) by Heinrich Zerkaulen—who was stationed on the eastern front in Reserve Infantry Regiment 251—in which a youth's passion for military service transforms him into a man.Footnote 21 (Gravely wounded, Zerkaulen survived and went on to welcome National Socialism in 1933, as did Engel, a political conservative whose Jewish heritage led to a publication ban and loss of his pension; he died impoverished, at age eighty-seven.) After Zerkaulen's poem, Engel explained that “Great pride in our male youth cheers us despite the following news.”

Patriotic writers felt inspired by the idea of singing “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles,” whatever else did or did not happen near Langemarck. Most prominent was Ludwig Ganghofer (a favorite of Kaiser Wilhelm II), who, at age fifty-nine, enlisted as a war correspondent and was so widely read that one general (according to a joke in circulation) waited to attack until Ganghofer showed up.Footnote 22 Ganghofer established a serial pamphlet sold to benefit soldiers titled Deutsches Flugblatt. In a lengthy Christmas story he supplied for the triple holiday edition of 1914, a St. Nicholas–type figure is delivering Christmas presents when he notices a dark area with a few campfires. “He arrived at many, many tiny mounds of fresh dirt” (soldier graves) and, bending down, patted them such as a father strokes his child's cheek. “Millions of voices,” both youth and men, began singing the Deutschlandlied. The song issued forth from all quarters—churches, hostels, castles, huts, stables, and so on, including the trenches—until, suddenly, a huge Christmas tree appeared, and gifts were distributed.Footnote 23

Walter Flex, an aspiring playwright who blossomed on the front as a writer (killed in action in 1917), took more freedom in his own fantastical “Christmas story about dead soldiers,” which he read to his comrades in a village church on December 24, 1914. In the story, a war widow and her son travel to a realm inhabited by fallen soldiers; every day, a new soldier has the job of “king,” whom God appoints to monitor the “music of the voices of the living” (that is, the activities on earth), assuring that “the music is pure, strong and pious, like a huge organ.” Music resurfaces in various roles, including metaphorical ones; for example, musical sounds emanate from the walls of this underworld. The king “ministers to the soul of his people and cares for them as if they were an old, holy organ.” Finally, “the poor woman listened and heard the living brothers of the gray guards singing on distant battlefields.”Footnote 24 Various poems “sung” within Flex's story circulated over the years and continued to be set to music well into the Third Reich.

The innocence of the youth slaughtered at Langemarck became defensive propaganda after the Germans became the first to deploy the mass use of poison gas in the spring of 1915. (Germans had used gas against the Russians four months earlier, but low temperatures counteracted its effect.) The British and French were surprised and unprepared, and the international community outraged, by the lethal chlorine gas attacks in the Second Battle of Ypres (April 22, April 24, and May 5). In the wake of this dishonorable victory, which seemed to dissolve heroism into the depravity of modern science, Germans needed to prove, as ninety-three illustrious writers and professors had attested in their October 4, 1914, manifesto, that Germany was ethically and culturally superior: we “believe that we will fight this war to the end as a nation of culture, to whom a Goethe, a Beethoven, and a Kant are just as sacred as its own hearth and home.”Footnote 25 Not just Germany's purpose but also its method in the war was claimed as ethical. As Thomas Mann put it in his infamous embrace of the war, from November 1914, “Our soldiery is spiritually connected to our moralism.” As Mann continued, “While other cultures embrace the structure of civilian cultivation and show a tendency towards refinement, including in art, German militarism is in truth the form and manifestation of German morality.”Footnote 26

One occasion to contemplate the meaning of soldiers singing as they charged was Cantate Sunday (the fourth Sunday after Easter Sunday—May 2, 1915), when sermons traditionally focus on liturgical music. The administrative head of the Southeast Diocese of the Saxon Lutheran Church, Paul Gennrich, gave a sermon on singing in the armed services.Footnote 27 Gennrich credited the Langemarck story to the official report, even though he sidestepped the question of whether Germany actually won: “With ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ on their lips, the youth in Belgium went to their death confident in victory (siegesgewiß).” His purpose was to show the moral fiber of the German soldiers whose courage was steeled through music. Such men, one can infer, do not shirk combat by resorting to gas canisters. “How much enthusiasm, how much joy in battle and courage in death, how much confidence in victory were released by ‘Die Wacht am Rhein,’ ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ and ‘Heil dir im Siegerkranz’! These songs fortify the will to fight, to win, and to die.” Gennrich spoke most forcefully about the ethical character of these men: “German song has prepared and helped to support our soldiers emotionally and morally for this battle.” Music was so influential, he believed, because German character had two parts: “the soft, sensitive, receptive heart and at the same time the steely, strong will to fight, both indivisibly blended together.” Veering toward fiction, Gennrich envisioned a similar heroism in the navy—but in a curious shift to the present tense: “When the battleship sinks, the crew on it, in the face of death, sings the Flaggenlied”—a song from 1883 (text by Robert Linderer and composed by Richard Thiele) that was enormously important in schools and the armed services alike.

Perhaps uncertain of the Langemarck anecdote's reliability, Gennrich reached back to Bismarck as an authority, citing the chancellor's 1893 speech to the Orpheus singing group: “To me, it is impossible to assess how much song prepared and facilitated our quest for unity.” The most gripping example, for Bismarck, was how singing “Wacht am Rhein” could build fortitude even through the winter when material support was scarce. Because German military superiority over the French derived from its troops’ enthusiasm and discipline, Bismarck explained, “I do not want to underestimate the German song as an ally in war.”Footnote 28

Gennrich's sermon was reproduced two months later in an East Prussian daily in the summer of 1915. He must have been pleased by the publicity—indeed, two years hence Gennrich would be the administrative head of the entire diocese of East Prussia. A music journal also reprinted much of the sermon; however, in an effort to reach out to all Germans, whatever their denomination, only the newspaper was credited, without reference to the source being a Protestant sermon.Footnote 29

A common source in histories of what became Langemarck Day is the extravagant account published in the Deutsche Tageszeitung on the first anniversary of the High Command's report, November 11, 1915. At a point of stalemate on the western front, with hundreds of thousands dead, many of whom had no proper burial, the author offered comforting language assuring the memory of those fallen soldiers. The young recruits at Langemarck established in their bravery “a monument as laudable, worthy, and durable as marble.” Dismissing traditional forms of commemoration (namely, a festive ceremony), the author proposed that when memorial holidays are formalized after the War, Langemarck Day should entail an hour of quiet reflection in every German school. The main point of such a commemoration would be that sorrow (Schmerz) is to be “overshadowed by pride in how they understood what it meant to fight and to die.” The Deutsche Tageszeitung commended the fresh volunteers because they “fought like old and experienced troops,” but the essayist, curiously, did not mention the detail of their singing.Footnote 30 Was the myth of singing at Langemarck insufficiently manly or somehow beneath the alleged objectivity of reportage?

Fissures in the military propaganda around Langemarck became everywhere apparent. No other newspapers drew attention to Langemarck on that alleged anniversary.Footnote 31 Not even High Command, in its daily report on November 11, 1915, mentioned Langemarck.Footnote 32 If forgotten as military history, the lore became all the more gripping in literary circles. It was that same poet and soldier, Will Vesper, who first harnessed the Langmarck myth as propaganda on September 2, 1915. In the absence of any legitimate story of German success near Langemarck, Vesper described soldiers in song during the German advance across the Yser, which involved capturing the towns of Keiem, Schoore, and Mannekensvere (October 18–21, 1914)—thus an entirely different location, seventeen miles north of the subsequent conflict in Bixschoote. Vesper knew that the purpose of song in battle was less a display of patriotism than a means of calming one's nerves, like wine:

The text of the Deutschlandlied appears in the description of their victory:

With its brash quotation from the Deutschlandlied, the poem offered meager inspiration to composers. The sole setting for voice and piano, published in a conservative cultural journal, was not publicized in the standard venue,Footnote 34 and the composer credited was probably a pseudonym, Robert Weise (the latter a term for a simple melody). The target audience was not soldiers. The “slow march” was through-composed (new music for every stanza), rather than a single strophe repeated for each of the poem's stanzas. The A minor dotted-rhythm for the first stanza suggests a simple funeral procession, though the references to the youth of the fallen soldiers (“Knaben, ist jeder noch ein Kind [repeated]”) bring a turn to the major mode:

In the middle two strophes, which re-create the action on the battlefield, the pace increases in the piano accompaniment. If the voice (as usual) represents the protagonists, the piano creates the atmosphere. Piano accompaniment is rare in war songs, and in this case the full chords, harmonic daring, and extended solo interludes are far in excess of the mostly stepwise movement of the voice. The piano part exposes the song as a bourgeois postcard of brave soldiers charging, not a song for soldiers. The final stanza brings closure by returning to the subject of the first—the dead soldiers—and recomposes the opening strophe with few changes. The inflections to major, which before showed the sweetness of the boy soldiers, here intimate their peace and comfort, buried in foreign land. The constraints of the rhyme scheme and the simple meter leave much unspoken, and hence the active role of the piano, making the tragedy palatable for listeners at home.

The appeal of this poetry is clear. Envisioning life in the trenches and on the battlefield was important back home, not least because modern warfare often precluded a proper burial and adequate information about how the death occurred. This rupture of mourning rites inspired a host of artists, especially women, to fill an emotional needFootnote 35—and also gave traction to the anecdote of brave soldiers who sang at the moment of their death.

In the Concert Hall: The Limits of Langemarck

The Langemarck narrative had its limits, however, for serious musicians. It might be appropriate for young brave soldiers to sing, but the concert hall was not the battlefield and the reluctance to exploit the Haydn string quartet was revealing. There was, to be sure, a spike in performances of the quartet, which was the progenitor of “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles,” and in particular the peculiar decision to extract the pertinent variations set (on “Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser”) that constitutes the third movement. But there is no evidence of musicians welling up at the report of singing at Langemarck nor any sign of composers moved to put pen to paper. The dogma of classical music as universal language across classes, as important as it was illusory, likely discouraged the reviewers at these performances from searching for parallels between current events and the concert hall. It seems obvious in retrospect that they wished to preserve the quasi-sacred status of classical music in bourgeois circles at a time when patriotic programming and benefit events flooded central European concert halls to the chagrin of most professional music critics.

Resistance to hearing a Haydn string quartet as political came partly from the social parameters of the genre. Unlike the broadly public traditions of patriotic choral music and symphonic music (which by dint of its sheer force had political resonance going back at least to the French Revolution), chamber music was heard in a smaller space by a presumably more elite audience. The rarified genre of string quartet, above all, was a feast for the mind and did not typically alight patriotic fervor. When Vienna's Rosé Quartet performed in Berlin in mid- or late November 1914, Wilhelm Altmann went so far as to refer to feeling an “immense consolation,” but he made clear that this emotional response was to the ensemble's superb playing, not their choice of repertoire—Haydn's “Kaiser Quartet,” Beethoven's Harp Quartet, Op. 74, and Mozart's B-flat major Quartet K458.Footnote 36

At a time when multi-movement works were not excerpted in public performance—unlike in the eighteenth century—the beloved Bohemian Quartet extracted the variations movement from the rest of the Haydn Quartet at the war benefit concerts they gave in several cities from mid-November through late December 1914. Although it is difficult to prove that the Langemarck report from November 11 inspired their plans, the critical reaction to the peculiar programming indicates that at least some understood the allusion to the war. A survey of reviews also illuminates stark contrasts in the response to Haydn's theme and variations movement in Habsburg cities (where the theme was the Kaiser Hymn) and in German cities (where the theme reminded listeners of “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles”).Footnote 37

In Vienna, the Bohemian Quartet opened their “war welfare” benefit concert with Haydn's variations movement. Ignoring any war-related basis for the programming decision, the old establishment critic (age seventy-one) Theodor Helm lavished praise on the Bohemians for using the “Kaiser Quartet” variations to honor the sixty-sixth anniversary of Franz Josef's accession to the throneFootnote 38—since the concert took place on December 2, 1914. In Prague, however, Ernst Rychnovsky was annoyed by the programming. In his first report since the war broke, Rychnovsky complained that “the concert season is struggling to gather momentum. It started with an evening of the Bohemian Quartet, organized for the purposes of war welfare causes, with the variations movement from Haydn's Kaiser Quartet as a lead-in.” As a Czech music specialist who later also wrote on Czech nationalist causes, Rychnovsky did not welcome a political symbol of the kaiser in the concert hall.Footnote 39

The larger issue, for most critics, was whether to welcome the Haydn variations as a more artistic expression of patriotism than so many freshly composed works or wring their hands at the intrusion of patriotism in the concert hall. In Berlin, the Bohemians’ concert (as the press fondly referred to the Bohemian Quartet) benefited the War Welfare Office in Bohemia and the German Red Cross. There was enormous enthusiasm for the event. The concert opened with the Bohemians’ beloved trademark, Smetana's Quartet “For My Life” (which depicted the composer falling into deafness), and concluded with the sensational Venezuelan pianist Teresa Carreño, some two years before her death, joining in Robert Schumann's Quintet, Op. 44. Haydn's variations movement came before the central work, Franz Schubert's famously lengthy and complex Quartet in G major. One reviewer did not register any qualms about the program or playingFootnote 40—which is unsurprising given the Bohemian Quartet received uniformly positive reviews over the years. But another, the old-guard Bruno Schrader (erstwhile student of Franz Liszt), objected to the “thoroughly superfluous war demonstration.” As if the Bohemians had betrayed the tacit understanding that the concert hall was a space in which ethnic and national differences were transcended, Schrader heard the ensemble as differently marked: their “grandeur and idiosyncrasy” came forth in the Smetana, and their “idiosyncrasy” in the Haydn, so much that the eighteenth-century composer's “simple melodic line” sounded like a “hot-blooded Slavic folksong.” (It was widely accepted that Haydn drew on a Croatian folk song in his Emperor's Hymn,Footnote 41 so the insult was well grounded.)

Later in this same report on Berlin musical life, Schrader vented against programming that referenced the war. Recounting a song recital by the great baritone Alexander Heinemann, Schrader wrote, “Unfortunately he, too, lapsed into concessions to wartime.” Most annoying to Schrader was that the text of standard repertoire (Schubert's “Am Tage aller Seelen” for All Soul's Day and Carl Loewe's ballade on Frederick the Great) was adapted to refer to the war. “This eternal playing of the war into the artistic freedom of the concert hall grates on one's nerves. The whole day one hears and reads about nothing other than the war, and not even in the evenings, in art, can one rise above this gruesome reality!” To conclude, he mused that “genuine patriotism” resists verbal description as does “true piety”—and here he quoted Jesus on the garrulous heathens.Footnote 42

The Bohemians’ programming of Haydn's variations movement also displeased a reviewer in Leipzig. Their first concert in Leipzig, in November 1914, included Haydn's full “Kaiser Quartet.”Footnote 43 When the Bohemian Quartet returned later that month to give a concert benefiting the Austrian Red Cross, Max Unger, a young musicologist who would go on to become a leading Beethoven scholar, willfully ignored Haydn's variations movement when he listed the works on the program. Unger would eventually, in 1942, qualify ideologically to be offered a position from top Nazi music administrators, and even in 1914, compared to his peers, Unger reached for national and cultural stereotypes more than his peers did. The Bohemian Quartet stood out for their “beautiful sensuous tone, sparkling and free rhythmic coordination, and gorgeous ensemble playing,” and Unger praised their interpretation of the Czech programming in the terms of cultural discipline—“they did not veer too much into the emotional as they savored Dvořák's bliss in music-making.”Footnote 44 Soon thereafter, Unger reported on the same performance for another journal, noting that the Haydn variations were “actually, from an artistic standpoint, superfluous,” presumably since the entire quartet had been played at their previous concert.Footnote 45

It seems likely that the Bohemian Quartet played Haydn's variations movement during each of their benefit concerts as a display of patriotism. Although there was no consensus among critics as to the precise significance of this programming, some adamantly denied any connection to the war. Two outlier responses are instructive.

When the Bohemian Quartet performed in Munich in January 1915, Erika von Binzer praised the “unusually high level” of their playing and found “incomparable pleasure” in the Schubert's “Death and the Maiden” Quartet, Beethoven's Quartet, Op. 59, no. 1, and to some degree also Smetana's “From My Life.” Yet as one of the few female music critics (her gender purportedly veiled by publishing under an initial) von Binzer did not appear to feel entitled to comment upon politics and the war. She observed tersely that Haydn's variations movement, which concluded the concert, was “uplifting.”Footnote 46 The composition itself, regal and staid, is by no means uplifting musically, but the enormous pride associated with the work may very well have had an uplifting effect on listeners.

During World War I—as again during the Third Reich—a number of compositions included the melody for “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles.” These were mostly the product of minor figures—compositions that were acknowledged as political, often to the chagrin of professional critics. Without a title or text that refers to Langemarck, these works are more likely patriotic in a more general sense and not responsive to the specific myth of Langemarck. One likely influence was an arrangement of Haydn's Kaiser hymn titled To Our Fallen Heroes, published within weeks of the November 11, 1914, report about Langemarck. The arranger was none other than the longstanding royal music director in Berlin, choral conductor Felix Blaesing. New lyrics were affixed to the hymn: two stanzas honoring the fallen soldiers are sung to the opening strophe; a third stanza empowering those who survive and calling upon them to pursue ethical virtues in their pursuit of victory. The culminating and final line was “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, über alles in der Welt!”Footnote 47 It was too meager a creative effort to warrant orchestration or even a chamber setting, but Blaesing felt compelled to produce arrangements for the most common ensembles—unaccompanied mixed chorus, three-part school chorus, voice with piano (December 1914), and unaccompanied men's chorus (January 1915).

It is striking, however, that composers meticulously avoided the theme of Langemarck, even despite its obvious significance to ideas of German musicality. The awkwardness, in aesthetic terms, of using music to represent music may be one reason composers drew no inspiration from Langemarck (until the Third Reich, when brash attempts to bring politics into music, and music into politics, left no room for aesthetic considerations).

The Langemarck Myth after World War I

The singing at Langemarck took on a new political valence after the enshrinement of “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles” as the national hymn. The president's declaration did not come with a vote in the Reichstag and was widely recognized as a concession to the right and others who protested the adoption of the black-red-gold national flag.

The idea of singing “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles” in battle became codified as right-wing propaganda by none other than Adolf Hitler. In a Landsberg jail from March to December 1924, writing Mein Kampf on the reams of paper delivered by Richard Wagner's daughter-in-law Winifred, Hitler reconstructed the scene at Langemarck, yet avoided the term itself. As an amateur stage designer and passionate opera spectator, Hitler gave a chiefly sonic description of the battle:

We marched in silence throughout the night and as the morning sun came through the mist an iron greeting suddenly burst above our heads. Shrapnel exploded in our midst and spluttered in the damp ground. But before the smoke of the explosion disappeared a wild “Hurrah” was shouted from two hundred throats, in response to this first greeting of Death. Then began the whistling of bullets and the booming of cannons, the shouting and singing of the combatants. With eyes straining feverishly, we pressed forward, quicker and quicker, until we finally came to close-quarter fighting, there beyond the beet-fields and the meadows. Soon the strains of a song reached us from afar. Nearer and nearer, from company to company, it came. And while Death began to make havoc in our ranks we passed the song on to those beside us: “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, über alles in der Welt.”Footnote 48

This passage has fascinated historians, who point out that there is no corroboration in Hitler's letters from shortly after the battle.Footnote 49 Moreover, in lieu of any personal recollection, Hitler relied on the collective “we” throughout.Footnote 50

Hitler's regiment was, however, ordered to shout “Hurrah” as they approached the enemy, and these hurrahs rippled across the fieldFootnote 51—a memory he may have translated into the myth of troops singing the Deutschlandlied in waves, each troop in turn. There is no hint of this experience in the detailed letter Hitler sent to his close friend Ernst Hepp on February 5, 1915, in which he tried to be as accurate as possible because he was re-creating a letter that had been lost. In fact, Hitler spent much of the battle lying on the ground and in trenches—hardly worthy material for Mein Kampf. The most intense moment was, again, the soundscape as the British attack unfolded: “While we lay pressed one against the other whispering and looking up into the starry sky, the distant noise drew closer and closer, and the individual thuds of the guns came faster and faster until finally they merged into one continuous roar. Each one of us could feel his blood pound in his veins.”Footnote 52 This fraught process of waiting for a battle in which so many of his own were shot was potentially transferred onto the sanitized anecdote about the Deutschlandlied. Later in Mein Kampf, “Deutschland über alles in der Welt” became a synecdoche for German domination:

What did universal suffrage matter to us? Is this what we had been fighting for during four years? It was a dastardly piece of robbery thus to filch from the graves of our heroes the ideals for which they had fallen. It was not to the slogan, “Long Live Universal Suffrage,” that our troops in Flanders once faced certain death but with the cry, “Deutschland über alles in der Welt.” A small but by no means an unimportant difference.Footnote 53

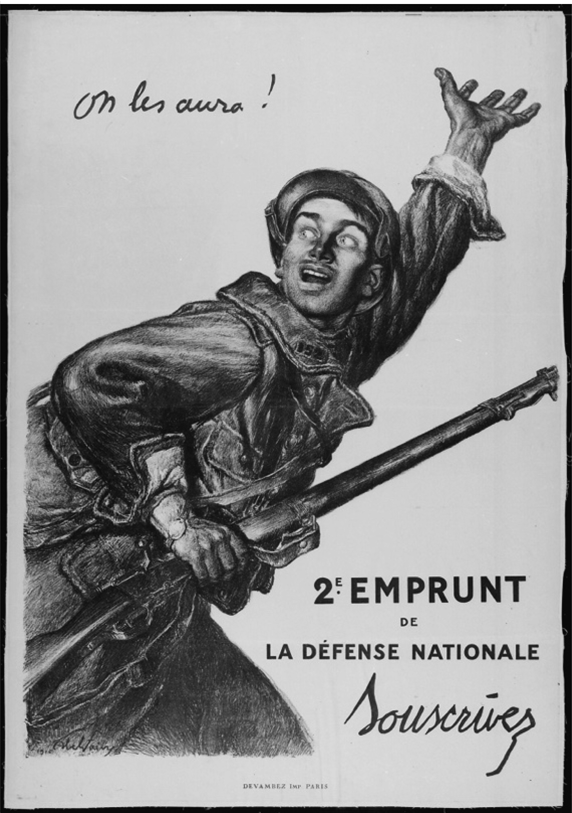

The idea of politicizing the soldiers singing the Deutschlandlied may have come to Hitler from the poem “The Dead of Langemarck,” appearing in a popular literary magazine in April 1924. Karl Gustav Grabe's poem is a nationalistic twist on Goethe's “Erkönig.” Riding through a stormy night, Satan mocks Germany for accepting unjust terms of peace. As the bell tolls midnight, one by one the bodies of the war dead rise from their graves, bloody and torn asunder from battle, until there is a “chorus” of thousands to sing the anthem:

At 1:00 am, the spirits vanish into their graves. Riding through the night, Satan explains the poem's message in a manner that would appeal to Hitler and other National Socialists, for whom January 30, 1933, would constitute a “revolution”:

Official regimental histories, many appearing in 1930s, tried to document the singing of the Deutschlandlied.Footnote 55 One reserve battalion supplied a practical basis for these anecdotes: “We think of the uncertainty and the upset of the previous night, but singing gives courage in need and in danger. We call to the storming comrades, ‘Whoever does not sing “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles,” is an enemy.’ … The singing penetrates ever more, until the whole German front at Bixschoote sings ‘Deutschland über alles,’ bellowing in turn.” The narrative shifts to the streets of Bixschoote, fighting man to man, with almost no ammunition; as the Scots enter this fray, “We throw them back, singing our Deutschlandlied. Finally Bixschoote is ours!”Footnote 56 The history of the Reserve Infantry Regiment 205, most closely associated with the November 11, 1914, report, recounts the tired German soldiers resting in the ruins of Bixschoote: a pianist revived his comrades with a dance and military marches, “and then as the commander gives the signal to march on, the one song that is capable of raising the departing men to the grandeur of this great day: with the song ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles,’ they depart for the front lines.”Footnote 57

* * *

In the twilight of the Weimar Republic, commemoration of Langemarck Day fell to youth and student organizations. For the tenth anniversary of the battle in 1924, the Bündische Jugend organized a camping trip. Some two thousand youth, including from Austria, traveled to the Rhön mountains at center of Germany, a forested region renowned for its remnants of Celtic and Roman civilizations. Rudolf Georg Binding's remembrance booklet documents the “grave sublimity” of the gathering, which cannot be reduced to incipient National Socialism.Footnote 58 On the first night, in pitch dark with torches, the participants stood shoulder to shoulder in rows that formed a huge square. A few men and boys sang a medieval Rhenish mass, “with tenderness, almost with love,” and another troop sang a death lament, accompanied by violins. A poet who had fought in the battle of Langemarck invoked “pride and mourning” for those who fell.

The flame from that first evening was preserved until the culminating commemoration the following day. (The ancient tradition of the Olympic flame would soon be revived—at the 1928 Summer Olympics.) Atop a nearby peak, an ancient slab near a clearing became the site of Langemarck commemoration on German soil. The consecration came through song—songs about death and the fatherland, the young singers aglow. In a classic description of ritual, Binding described commemoration of the youth from Langemarck through a litany of all sources of dissention that fell away, concluding that “no differences in appearance, denomination, race, social status, or statehood disturbed the commemoration of purely noble disposition. Here nothing separated us; will and action became one.” The unveiling of the memorial—a feat of scouts turned kitsch, with the letters “Langemarck” spelled in small flags and streamers—proved so moving, in its mythic grandeur, vitality, and inwardness, that all were speechless. After brief readings of Friedrich Hölderlin and Friedrich Nietzsche, the speaker chosen by the youths proclaimed, “We are now worthy of singing the German song, the Song of Langemarck. ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ roared from the souls towards heaven, just as it may have on rare occasion resounded from each hero himself, in the same mindset.”Footnote 59 Binding left no doubt over the political utility of Langemarck, even if his romantic leanings would later annoy Hitler Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach, among others.

The embrace of Langemarck by university student organizations is unmistakable, especially as right-leaning factions came to dominate.Footnote 60 At a national gathering in Eisenach in the summer of 1930, student representatives envisioned the government as seeking to disrupt or suppress pan-Germanism and “patriotic renewal.” Langemarck, as one participant recalled, became a call to action: “This word has become a living strength, which shakes those who slumber and propels those who hesitate.” For Germans who could not visit the Langemarck cemetery in Belgium, the student union gathered writings and other creative works about Langemarck and World War I, published in time for the first Langemarck Day in the Third Reich.Footnote 61

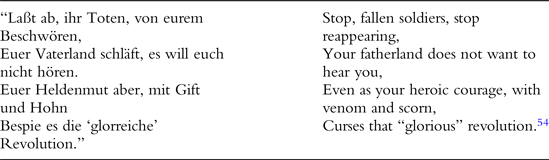

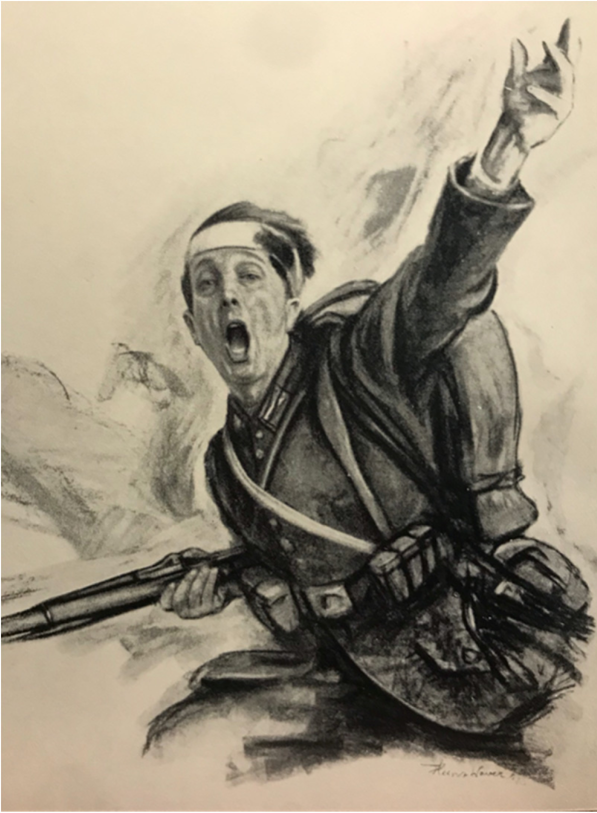

The book reproduced an engraving by Heinz Wever, who had served on the western front. It originated as a wedding present for Prince Wilhelm of Prussia from the Stahlhelm-Studentenring Langemarck, the paramilitary group he had joined years earlier (image 1). It is possible that the soldier, who charges in vigorous song, despite the bandaged head wound, was an allegory for Wilhelm defying his grandfather (the former Kaiser) in both joining the Stahlhelm and marrying beneath his rank. But Wever, poised to become a leading propagandist, was more likely seeking to outdo the fabled enemy poster, created by Abel Faivre in 1916 (image 2). The French soldier points toward battle, looking behind him to encourage others to follow; the diagonal exudes energy, as do the strong lines formed by his outstretched arm and gun. The entire design expresses the exclamation point in the title, On les aura!. By contrast, Wever's soldier sings forcefully, as if approaching the viewer. Faivre, moreover, pictured a boyish face in order to convince the French public to support the troops by subscribing to the defense loan. Yet the soldier's outstretched hand—disproportionately large and muscular—bears gritty details that vouch for his strength, unlike the idealized shaded lines of the German singer. The German trumps the French youth in the force of sound. The French soldier's mouth is open, but the call to battle, written out above his head, was well known as General Pétain's at Verdun (and itself a quotation from Joan of Arc). By contrast, the German extends his free hand in an operatic pose, the exertion showing in the tendons near his wrist. Even as the lowered eyelids suggest fatigue, perhaps the peace of death, and his grip on the gun is relaxed. The soldier exults in patriotic song.

Image 1. Heinz Wever, Langemarck 1914.Footnote 62

Image 2. Abel Faivre, On les aura! (Lithograph, 1916)

In short, it is the German soldier who truly sings, and whose song we know. The title of the engraving suggests both: the Langemarck narrative fused death, heroism, and song in a potent mix of sound and manufactured memory that helped sustain German nationalism from one war to the next. The song itself, thanks to Haydn's music, could survive as the national anthem of the Federal Republic and then of unified Germany after 1989, with its third verse celebrating brotherhood replacing “Deutschland über Alles.” The German counterpart to the French Lieux de memoire volumes includes Fallersleben's song as a site of memory. Did the recruits at Langemarck sing joyously as they were mowed down? It hardly mattered to those who helped themselves to the memory: the music and the words found new voices as surely as the silenced voices may have earlier found their song.

The popular embrace of the Langemarck myth—in poetry, in memoirs, and other lore—shows the vulnerability of German society and culture to aestheticization be it to elevate soldiery or political control. This gripping story, captured in the mellifluous sound of a word that was itself almost musical, “Langemarck” sustained a dream of heroism on the battlefield that energized nationalist Germans through World War II.