Box 1. Definition of key terms.

Environmental flows: ‘[Q]uantity, timing, and quality of freshwater flows and levels necessary to sustain aquatic ecosystems which, in turn, support human cultures, economies, sustainable livelihoods, and well-being’ (Arthington et al. Reference Arthington, Bhaduri, Bunn, Jackson, Tharme and Tickner2018, p. 2)

Environmental water: ‘[E]ncompasses all water legally available to the environment through the array of possible allocation and legislative mechanisms. Each year, the precise volume of environmental water actually allocated or remaining under these legal mechanisms may vary depending on overall water availability, demands, and priorities’ (Horne et al. Reference Horne, O’Donnell, Webb, Stewardson, Acreman, Richter, Horne, Webb, Stewardson, Richter and Acreman2017b, p. 2)

Legitimacy: This has been defined to include both input and output legitimacy (Hogl et al. Reference Hogl, Kvarda, Nordbeck, Pregernig, Hogl, Kvarda, Nordbeck and Pregernig2012). Input legitimacy focuses on the process and the level of acceptability to people affected by the programme. Input legitimacy requires explicit consideration of access, equal representation, transparency, accountability, consultation and cooperation, independence and credibility. Output legitimacy focuses on the solution and whether the intervention actually solved the problem or otherwise achieved its goal. Output legitimacy emphasizes outcomes, including awareness, acceptance, mutual respect, active support, robustness and common approaches to shared problem-solving (see also O’Donnell et al. Reference O’Donnell, Horne, Godden and Head2019b)

Introduction

The Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly 1992) duly recognizes the ongoing conflicting nature of water allocations due to increasing human demands, urbanization and climate change. Pleas for access to water are being sounded not only from people, but also from the environment more generally. This ongoing disputation prompted global action to protect ecological systems of waterways, thus giving rise to the concept of ‘environmental water’ in the 1990s (Poff et al. Reference Poff, Allan, Bain, Karr, Prestegaard and Richter1997, Tickner et al. Reference Tickner, Opperman, Abell, Acreman, Arthington and Bunn2020). Environmental water (also sometimes referred to as ‘environmental flows’; see Box 1) refers to water allocated specifically for the maintenance, regeneration and sustainability of waterway ecosystems (Arthington et al. Reference Arthington, Bhaduri, Bunn, Jackson, Tharme and Tickner2018). Although essential for the protection of river health and sustainable river management, the belated acknowledgement of environmental water also increased contestation between water users in overallocated systems where water had to be recovered from existing users to provide for the environment (Horne et al. Reference Horne, O’Donnell, Tharme, Horne, Stewardson, Webb, Acreman and Richter2017a).

Many countries – including Australia, the USA, Canada, China and South Africa – have implemented environmental water management policies (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell and Brebbia2013, Harwood et al. Reference Harwood, Johnson, Richter, Locke, Yu and Tickner2017) using a range of different mechanisms to allocate water to the environment, broadly categorized into: (1) creating a right to water for the environment; or (2) placing conditions on the use of water by others (such as caps, daily limits on extraction or water release from storage; Horne et al. Reference Horne, O’Donnell, Tharme, Horne, Stewardson, Webb, Acreman and Richter2017a). Where resources in a system are limited, recovering water for the environment can be achieved through investing in irrigation efficiency, administrative reallocation and/or market-driven reallocation (Meinzen-Dick & Ringler Reference Meinzen-Dick and Ringler2008).

However, reallocation of water is not easy, and water has become highly politicized as a result (Kemerink et al. Reference Kemerink, Ahlers and van der Zaag2011, Sultana & Loftus Reference Sultana and Loftus2012, Hart Reference Hart2015, Hanasz Reference Hanasz2017, Walker Reference Walker2019). Decisions regarding environmental water allocations are among the most highly charged, with distributional effects producing winners and losers from policy reform (Charney Reference Charney2005, Macpherson et al. Reference Macpherson, O’Donnell, Godden, O’Neill, Holley and Sinclair2018, O’Donnell et al. Reference O’Donnell, Garrick and Horne2019a). There are many differing perspectives on how to provide environmental water, how much to provide and who gets to decide. Understanding community perceptions of environmental water will help us to navigate this contested space.

Since its emergence from the physical sciences, environmental water management has seen an expansion in interdisciplinary approaches over the last 20 years (Horne et al. Reference Horne, O’Donnell, Webb, Stewardson, Acreman, Richter, Horne, Webb, Stewardson, Richter and Acreman2017b, Poff et al. Reference Poff, Arthington, Tharme, Horne, Webb, Stewardson, Richter and Acreman2017). There has been a growing recognition of the importance of participatory processes for water planning and management (Conallin et al. Reference Conallin, Dickens, Hearne, Allan, Horne, Webb, Stewardson, Richter and Acreman2017, Mussehl et al. Reference Mussehl, Horne, Webb and Poff2022), including perspectives from local communities as well as Indigenous peoples (Pahl-Wostl et al. Reference Pahl-Wostl, Arthington, Bogardi, Bunn, Hoff and Lebel2013, Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Cosens, Jackson, Leonard and McCool2018, Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Jackson, Tharme, Douglas, Flotemersch and Zwarteveen2019). Similarly, there is also a growing awareness that the legitimacy of water allocation and planning stems from both the outcomes achieved (healthy river systems) and the processes used (in which all members of the affected community have had an opportunity to be heard; O’Donnell et al. Reference O’Donnell, Horne, Godden and Head2019b). As water management becomes more contested under climate-induced water scarcity, the way in which decisions are made in water policy is becoming increasingly scrutinized in the public arena. Water managers and policymakers are more aware of the importance of community and stakeholder input into water planning (Conallin et al. Reference Conallin, Dickens, Hearne, Allan, Horne, Webb, Stewardson, Richter and Acreman2017, Schirmer Reference Schirmer, Hart and Doolan2017), which has led to investment in research into citizen science and stakeholder engagement in water management. Inclusion of communities in planning offers a pathway to increased legitimacy in policy choices and increased acceptance of those policy outcomes (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Jackson, Tharme, Douglas, Flotemersch and Zwarteveen2019), but gauging perceptions is often very difficult. What common themes and points of difference emerge across multiple contexts? This paper aims to address this question by reviewing the existing literature using a narrative review approach (Bryman Reference Bryman2016) and providing an evaluation for future directions.

Review methodology

We conducted a search of peer-reviewed scholarship (including dissertations) published in English up to April 2021 (Table 1). Articles were sourced through the databases Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar and ProQuest using the search terms in Table 1. The timeline for the search had no start date. The initial search yielded 538 articles (Table 1). In finding appropriate search terms for this study, we settled on using the globally accepted terminology of ‘environmental flows’, a term that has been the global standard since the Brisbane Declaration (International River Foundation 2007). In attendance for the Brisbane Declaration were over 800 researchers and practitioners from 57 nations. More recently, this had been reaffirmed as preferred terminology in 2018 (Arthington et al. Reference Arthington, Bhaduri, Bunn, Jackson, Tharme and Tickner2018). It is, however, important to note that the terminology on environmental flows has varied in the past, and this may affect the results. It could explain the greater number of Australian studies found in the literature search, as the term has had a more widespread use in Australia than elsewhere.

Table 1. Literature review search terms and articles found using Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar and ProQuest.

This search incorporated grey literature, of which two were included as additional evidence in this review (see Loo et al. Reference Loo, Penko and Carpenter2018, Murray–Darling Basin Authority & Orima Research 2021).

The majority of the identified articles were technical in approach, exploring data-driven ecological indicators of river systems. The abstract of each article was reviewed to determine its relevance to the research scope of community perceptions in environmental water management. This resulted in 46 articles: 21 were analytical and 25 were theoretical. This field is interdisciplinary: articles came from various fields of study such as economics, environmental studies, geography, policy, planning and management, law, urban planning and engineering. The 46 papers were then subjected to open inductive coding using the NVivo program by extracting themes from each article, categorizing them and comparing them to one another (Bryman Reference Bryman2016). It should be noted that there are a number of limitations within this study. These include limiting articles to those that are peer reviewed (bar the two reports mentioned) and in English.

Literature overview

While there are large numbers of publications on environmental water generally (yielding over 9000 hits in Web of Science), only 46 linked environmental water to community perceptions, indicating that this research area remains in its infancy. However, the number of articles has had an upward trajectory in the last 20 years (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Academic publications on environmental water and community perceptions: number of articles per year. 3 per. Mov. Avg. = three-point moving average.

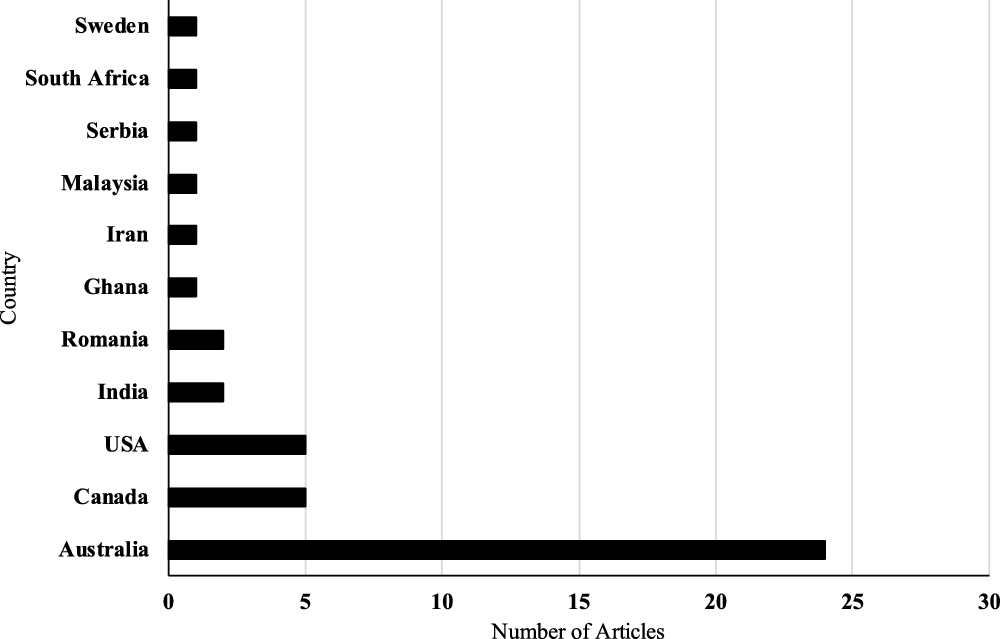

The studies are overwhelmingly based in Australia, followed by those in the USA and Canada (Fig. 2). Although the study methodology did not exclude any geographical locations and utilized global search tools, the predominance of the literature from Australia is probably due to the mature nature of environmental water policy in Australia, in particular its market-based approach to water allocation (Garrick et al. Reference Garrick, Siebentritt, Aylward, Bauer and Purkey2009, Grafton & Wheeler Reference Grafton and Wheeler2018).

Fig. 2. Location, by country, of the studies found in the literature review.

Key themes

Articles either discussed the conceptual basis for stakeholder engagement and key emerging themes from stakeholder groups or included empirical studies of stakeholder perceptions of environmental water (see Table S1 for a full breakdown of the empirical articles).

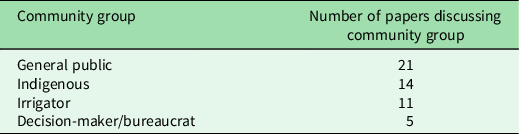

Detailed analysis of the empirical studies provided quantitative or qualitative measurement of the ways in which different groups perceive environmental water. The most common groups were the general public, Indigenous peoples, irrigators and water decision-makers (bureaucrats, water agencies, government departments, etc.; Table 2).

Table 2. Different definitions of ‘community’.

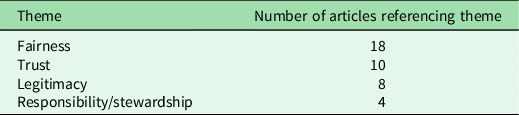

The review of all of the relevant papers highlighted a core theme of legitimacy and fairness permeating the discussion (Table 3). Public perceptions of environmental water both shape and are shaped by people’s perceptions of the legitimacy and fairness of the allocation process. As these perceptions also affect the level of political support for environmental water policies, a better understanding of public perceptions of different groups is therefore critical in designing policy approaches. Doing so will also centre not just ecological science, but the broader socio-ecological system and the social interactions that define it.

Table 3. Key themes from qualitative coding.

Perceptions of different communities

General public perceptions

There are limited academic studies specifically addressing general public perceptions of environmental water, and it is important to acknowledge the contextual factors within these studies, as the majority of them were undertaken within Australia (e.g., Mendham & Curtis Reference Mendham and Curtis2018, Syme et al. Reference Syme, Nancarrow and McCreddin1999), Canada (e.g., Bjornlund et al. Reference Bjornlund, Xu and Zhao2014) and the USA (e.g., Mott Lacroix et al. Reference Mott Lacroix, Xiu and Megdal2016). Each of these locations (refer to Table S1 for the full list) has differing underlying cultural associations with water, and this may affect attitudes towards the allocations.

Most of these studies separated the respondents into groups or clusters. These were organized either by common values (Parrack Reference Parrack2010, Bjornlund et al. Reference Bjornlund, Zuo, Parrack, Wheeler and De Loë2011, Mendham & Curtis Reference Mendham and Curtis2018), by activity (Mendham & Curtis Reference Mendham and Curtis2018), by occupation (Mott Lacroix et al. Reference Mott Lacroix, Xiu and Megdal2016) or by location (Bjornlund et al. Reference Bjornlund, Zuo, Parrack, Wheeler and De Loë2011). These studies show that personal values strongly correlate with policy preferences in environmental water management (Bjornlund et al. Reference Bjornlund, Zuo, Parrack, Wheeler and De Loë2011, Reference Bjornlund, Parrack and De Loë2013a). Unsurprisingly, those that held pro-environmental values have the most positive judgements of the benefits of environmental water (Mendham & Curtis Reference Mendham and Curtis2018).

Pro-environmental groups that are prevalent among urban dwellers also prefer greater government intervention, while the pro-economic groups prefer limited government involvement, with a predilection for market-driven forces (Parrack Reference Parrack2010, Bjornlund et al. Reference Bjornlund, Parrack and De Loë2013a, Reference Bjornlund, Zuo, Wheeler, Xu and Edwards2013b). Urban dwellers also expressed a normative desire to increase flows for environmental use, which runs in contrast to pro-economic groups, which orientate towards the retention of water within the irrigation sector (Parrack Reference Parrack2010). Similarities have been reported between these two contesting groups: both pro-environmental and pro-economic clusters agreed on set minimum flows for rivers and that only water above those minimum flows should be flagged for economic purposes (Parrack Reference Parrack2010). Mendham and Curtis (Reference Mendham and Curtis2018) reported that only 24% of public respondents agreed that the benefits of environmental water outweighed any of its drawbacks, with 36% disagreeing and 30% unsure. Negative judgements of environmental water were from farmers, non-town (rural) people and non-walkers. Highest positive judgements came from birdwatchers and walkers, emphasizing the importance of relationships with nature in determining river values. Trust factors were present, with those that have affirmative judgements also being positively associated with increased levels of trust in the water management agency (Mendham & Curtis Reference Mendham and Curtis2018).

Market research commissioned by the Victorian Environmental Water Holder in Australia in 2017 showed that, in general, levels of water literacy were low in the general public, with only 16% of respondents being aware that Victoria’s waterways had been modified by human activities (Loo et al. Reference Loo, Penko and Carpenter2018). Only 17% of respondents had heard of environmental water. After environmental water had been explained, 66% were supportive of the concept. Although some had strong opinions (10% opposed, 26% supported), the majority (64%) remained ambivalent and unsure. Measuring perceptions of environmental water in the public is not without its difficulties, considering the lack of general knowledge and disinterested attitudes towards the concept (also a key finding in Mott Lacroix et al.’s (Reference Mott Lacroix, Xiu and Megdal2016) study in the USA).

Indigenous perspectives

Many of the studies focused on the recognition of Indigenous cultures and identities in environmental water management, but all of these (except one: Mott Lacroix et al. Reference Mott Lacroix, Xiu and Megdal2016) were located within the Australian settler-colonial context. These studies aimed to document the views of different Indigenous communities on environmental water, recognizing the often-porous borderline between environmental water and cultural flows. The term ‘cultural flows’ refers to a group’s requirements for a certain quantity of water to maintain human interactions and relations with their river systems (Jackson Reference Jackson and Wohl2021). It is often used in conjunction with First Nations groups, which require cultural flows (or ‘cultural water’) to ensure the cultural continuity, survival (including spiritual) and maintenance of traditional life (Australian Cultural Heritage Management 2014).

The laws and cultural protocols of First Nations and Traditional Owners encompass a sense of stewardship and responsibility in managing land and water using traditional knowledge (Jackson Reference Jackson2015). Although First Nations peoples have never ceded their rights to water and explicitly state their desire to exercise authority over its management, it remains the role of government departments and agencies to make the case for environmental water (Jackson Reference Jackson2015, Reference Jackson, Horne, Webb, Stewardson, Richter and Acreman2017). The modernist principle upon which water management is based, particularly its strong reliance on Western forms of data collection (Hartley & Kuecker Reference Hartley and Kuecker2020), largely ignores the knowledge and cosmologies of Traditional Owners (Jackson Reference Jackson2015, Yunkaporta Reference Yunkaporta2019). Current water management objectives do not fully incorporate diverse knowledge claims into practices and ignore species of high cultural importance to Indigenous peoples (Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Bark, Garrick and Pollino2015).

Indigenous values often do not align with non-Indigenous environmental values, forcing Indigenous peoples to advocate for their inherent right to cultural flows (Yates et al. Reference Yates, Harris and Wilson2017, Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Godden and Lindsay2018, Curley Reference Curley2019, O’Donnell et al. Reference O’Donnell, O’Bryan and Godden2021). Environmental degradation of rivers contributes to a loss of cultural identity of Traditional Owners, with associated spiritual, physical and mental health impacts. The sense of grief that underpins this change in environment is wholly felt by those in Conroy et al.’s (Reference Conroy, Knight, Wassens and Allan2019) study, with losses of bird life and freshwater fish having a profound effect on Indigenous community relationships with the land and water. As Jackson (Reference Jackson, Horne, Webb, Stewardson, Richter and Acreman2017, p. 176) notes: ‘For Indigenous peoples, the contamination, diversion, and depletion of water bodies represent an attack on collective identities and survival as peoples as well as their direct health and well-being.’

This interdependence between the cultural management of water and healthy ecosystems lends itself to the comingled nature of environmental water and cultural flows, frequently leading to the conflation of the two. A focus group participant in Conroy et al. (Reference Conroy, Knight, Wassens and Allan2019, p. 177) stated: ‘But environmental water is just like cultural water, to me. It’s all from the same thing.’

Researchers and Indigenous advocacy groups generally regard current environmental water management to be separating ecological indicators for the river from its social and cultural contexts, resulting in a dichotomy that continues to disenfranchise Indigenous peoples (Nikolakis et al. Reference Nikolakis, Grafton and To2013, Jackson Reference Jackson2015, Reference Jackson, Horne, Webb, Stewardson, Richter and Acreman2017, Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Bark, Garrick and Pollino2015, Conroy et al. Reference Conroy, Knight, Wassens and Allan2019). Conroy et al.’s (Reference Conroy, Knight, Wassens and Allan2019, p. 178) study described the potential disempowering effects on to Indigenous groups of issuing cultural water licences, stating that ‘the allocation of a small cultural water licence, while potentially beneficial to the health of a small number of individual waterbodies, may have the perverse outcome of limiting Indigenous people’s involvement in broader conversations around environmental water planning and delivery, because it creates a potentially false dichotomy between environmental and cultural values’. Although environmental water is not the same as cultural water, Indigenous peoples have expressed a strong interest in managing environmental water (Jackson & Nias Reference Jackson and Nias2019), a sentiment echoed by a Traditional Owner in Victoria who stated that ‘all water is Aboriginal water’ (O’Donnell et al. Reference O’Donnell, O’Bryan and Godden2021, p. 5).

Indigenous peoples in the Northern Territory of Australia were overwhelmingly not in favour of managing environmental water through market mechanisms, citing the danger of economic interests trumping those of the environment (Nikolakis et al. Reference Nikolakis, Grafton and To2013). Unless environmental water management practices recognize the role of Indigenous peoples in the stewardship of these rivers and the role of river systems in the provision of food, medicine and cultural practices, the allocation and management of environmental water will continue to exacerbate the impacts of colonization (Nikolakis et al. Reference Nikolakis, Grafton and To2013).

Irrigator perspectives

In the contestation for scarce water, irrigators represent a group for which a reliable supply of water has a direct causal relationship with production, economic livelihoods and the livelihoods of the wider community. Typically, environmental water allocation systems have shown lag times in recognizing the overallocation of water to irrigation uses, with the water needing then to be reallocated to the environment (Garrick et al. Reference Garrick, Siebentritt, Aylward, Bauer and Purkey2009, Lane-Miller et al. Reference Lane-Miller, Wheeler, Bjornlund and Connor2013).

The empirical studies considered not only irrigators’ willingness to give up water rights, but also their understanding of the instream environmental degradation caused by changed flow regimes. In Australia, irrigators’ recognition of the importance of environmental water dropped from 60% recognition in 1998 to 35% in the mid-2000s, before rising to 44% recognition in 2010–2011 (Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, Zuo and Bjornlund2014). A noteworthy drought from 1996 until 2010 is likely to have had a prominent impact upon farmers’ perceptions. Of those irrigators willing to donate their own water allocation to the environment, 81% recognized the environmental need for the flows, while those that sold any of their allocation in that season were also more likely to donate their allocation to the environment (Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, Zuo and Bjornlund2014). In the Murray–Darling Basin, 86% of irrigators were aware of the need for environmental water, but 33% of water access entitlement holders distrusted the scientific information (hydrological and ecological data) underlying environmental flow decisions (Graham Reference Graham2009, Murray–Darling Basin Authority & Orima Research 2021). A total of 82% of farmers particularly distrusted water information relayed by government agencies (Murray–Darling Basin Authority & Orima Research 2021), corroborating the findings from a previous study by Wheeler et al. (Reference Wheeler, Hatton MacDonald and Boxall2017). Without trust in experts and water agencies, it is difficult to provide ‘proof’ of the benefits of environmental water that will be considered by and in turn alter farmers’ acceptance of environmental water decisions. This is especially true in light of the lack of directly observable benefits of environmental water allocations when visiting rivers (Lukasiewicz & Dare Reference Lukasiewicz and Dare2016).

In both Australia and the USA, values that relate to family and lifestyle had a large influence on decisions to participate in environmental water buyback schemes, with many feeling pressure not to sell water outside of their immediate communities (Lane-Miller et al. Reference Lane-Miller, Wheeler, Bjornlund and Connor2013). In Canada, clusters of values reflecting broad worldviews on the environment and the economy had a statistically significant association with selling water rights (Hall Reference Hall2014). At the time of that study, water was extremely scarce, and most irrigators had the intention to buy water, not to sell their allocation, although those that did decide to sell were more likely to be doing this based on a pro-environment worldview (Hall Reference Hall2014).

In the USA, non-governmental organizations and water trusts helped to increase the willingness of irrigators to sell their allocated water through fostering trust with the broader community. Lane-Miller et al. (Reference Lane-Miller, Wheeler, Bjornlund and Connor2013) described the impact of the Oregon Water Trust in developing diverse methods of water trading such as split season leasing, source switching, diversion changes and modified land management. The wide range of options and the investment of time and money in developing context-specific water buyback arrangements that keep farmers on the land helped to improve trust and drive participation.

Decision-maker perspectives

The perceptions and attitudes of decision-makers such as water policymakers, water resource managers and government officials towards the allocation and management of environmental water have been the least represented in studies. Lukasiewicz et al. (Reference Lukasiewicz, Syme, Bowmer and Davidson2013) and Wineland et al. (Reference Wineland, Fovargue, York, Lynch, Paukert and Neeson2021) discuss these perceptions of decision-makers, albeit with differing contextual environments and study aims. In an Australian study of social justice in the management of water using market-based approaches (i.e., water as a property right), a key finding was the difference in the ways in which government water managers and participants from the general public saw the environment (Lukasiewicz et al. Reference Lukasiewicz, Syme, Bowmer and Davidson2013). While government managers perceived the environment as representing ‘interconnecting ecosystems, fragile habitats and degraded landscapes which need to be protected from further human encroachment’, landholders saw it as their ‘surrounding and resources to be lived in, used and enjoyed’ (Lukasiewicz et al. Reference Lukasiewicz, Syme, Bowmer and Davidson2013). This is a key distinction between adopting a paternal, protective approach to environmental management and adopting the landholder view of the environment as a commodity. This stark contrast between the government and the landholder views results in vastly differing policy preferences that drive a schism between the groups.

In a Texas and Oklahoma (USA) survey of water and natural resource managers, the contrast between these groups was measured based on whether they had bearish (pessimistic about current and future environmental water) or bullish (optimistic about current and future environmental water) outlooks (Wineland et al. Reference Wineland, Fovargue, York, Lynch, Paukert and Neeson2021). The largest difference between these groups was stakeholders’ willingness to participate in environmental water programmes: the bearish group ranked this as least important in their assessment of environmental water programmes, while the bullish cluster recognized it as their second most important factor (Wineland et al. Reference Wineland, Fovargue, York, Lynch, Paukert and Neeson2021). However, Texas and Oklahoma do not currently have any provision in place for ensuring the allocation of environmental water along waterways (Wineland et al. Reference Wineland, Fovargue, York, Lynch, Paukert and Neeson2021), which makes it different from New South Wales and South Australia that had implemented such environmental flow requirements (Lukasiewicz et al. Reference Lukasiewicz, Syme, Bowmer and Davidson2013). The Wineland et al. (Reference Wineland, Fovargue, York, Lynch, Paukert and Neeson2021) study was also limited to 24 responses, which may not be representative of the cohort of decision-makers.

A qualitative analysis of interviews with environmental water managers and policymakers in south-eastern Australia and western USA highlighted the differences in approach between these two jurisdictions (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell2018). In Australia, the focus within environmental water allocation and management during 2007–2017 was on ecological health, with limited investment in demonstrating the outcomes for communities, while in western USA the focus was much more strongly on the role of communities, as achieving environmental flow was only considered successful if it also achieved public support.

Discussion

Fairness, trust and legitimacy

The most cited theme in the literature is the importance of fairness in environmental water allocations. Public perceptions of fairness are crucial in order for water policies to be considered acceptable by communities (Syme et al. Reference Syme, Nancarrow and McCreddin1999). However, there are differing perceptions of fairness, of how best to establish fair allocations of water (Garrick et al. Reference Garrick, Siebentritt, Aylward, Bauer and Purkey2009, Lane-Miller et al. Reference Lane-Miller, Wheeler, Bjornlund and Connor2013, Lukasiewicz et al. Reference Lukasiewicz, Syme, Bowmer and Davidson2013) and of how to fairly spread the burdens of delivering environmental water (Lukasiewicz & Dare Reference Lukasiewicz and Dare2016).

Community engagement in environmental water decision-making is increasingly prescribed to include participatory processes in water law and policy. However, in practice, bureaucrats often rely on mere information sharing, falling short of genuine power-sharing engagement (Arnstein Reference Arnstein1969, Innes & Booher Reference Innes and Booher2004) and best practice in public participation (Durham et al. Reference Durham, Baker, Smith, Moore and Morgan2014, Godden & Ison Reference Godden and Ison2019). This results in processes that are technocratic and expert-led, often denying genuine engagement with communities (Srdjevic et al. Reference Srdjevic, Funamizu, Srdjevic and Bajčetić2018, Kosovac et al. Reference Kosovac, Hartley and Kuecker2021). Without fair and equitable consultation with these groups, the processes serve to delegitimize government decisions on environmental water, causing a reduction in acceptance of contentious allocations (Syme et al Reference Syme, Nancarrow and McCreddin1999, Godden & Ison Reference Godden and Ison2019, O’Donnell et al. Reference O’Donnell, Horne, Godden and Head2019b).

Fairness and legitimacy both affect communities’ trust in water institutions. Trust, which not only forms an integral part of social capital (Putnam Reference Putnam2000) but also aids in the transfer of information effectively (Mumbi & Watanabe Reference Mumbi and Watanabe2020), is another factor in the public acceptance of environmental water policy. One of the challenges for establishing trust in water institutions is a reported anti-government and anti-expert cynicism (Graham Reference Graham2009, Murray–Darling Basin Authority & Orima Research 2021). Thus, in the Murray–Darling Basin in Australia, community engagement (including with Indigenous peoples) was government-mandated, but the outcomes were highly variable. Of the 20 water proposal plans submitted by the state of New South Wales for approval under the federal process, 19 were initially rejected for reasons including failure to engage adequately with Indigenous peoples (Davies Reference Davies2021).

However, careful consideration of how stakeholder groups are organized is required to ensure acceptance and legitimacy. A lack of transparency, working group turnover and high exclusivity of the group will not be readily accepted as effective localism in environmental water decision-making (Dare & Lukasiewicz Reference Dare and Lukasiewicz2019). In Australia, where environmental water managers have publicly referred to themselves as ‘the largest irrigator in the basin’ and have participated in the water markets, there has been a discernible shift in communities’ willingness to support environmental water (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell2017). This is in stark contrast to western USA, where environmental water managers actively seek to create and renew trust with each water recovery (Gilson & Garrick Reference Gilson, Garrick and Wheeler2021).

The distributive justice principle of ‘need’ overlays much of the discussion surrounding water allocation (Lukasiewicz et al. Reference Lukasiewicz, Syme, Bowmer and Davidson2013). The perception of fairness and environmental water is positioned within a general view that higher levels of water efficiency should be considered more deserving of use (Syme et al. Reference Syme, Nancarrow and McCreddin1999, Lukasiewicz et al. Reference Lukasiewicz, Syme, Bowmer and Davidson2013) and that existing irrigation rights should be honoured. Much of the commentary on environmental water and stakeholder perceptions links to the reallocation of water to the environment from consumptive water users. In parts of Australia, Canada, the USA and South Africa, a neoliberal market approach to trading water in water-stressed areas has been a central plank of water policy (Wheeler Reference Wheeler2021). The overarching logic behind the market is to ensure that quantities of water are allocated to the highest economic value for their use (Freebairn Reference Freebairn and Bennett2005). In a number of regions (e.g., Australia and western USA), government agencies and non-governmental organizations have entered the water market on behalf of the environment in a bid to recoup some of the missing flows that work to sustain the ailing flora and fauna along rivers (Garrick & O’Donnell Reference Garrick, O’Donnell and Bennett2016). The environment is then considered ‘another water user’ with water rights equivalent to those held by other consumptive water users, which can further erode support for environmental protection (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell2017). The commodification of water resources is often seen as not being complementary to the way in which many communities understand and culturally manage natural resources (Swyngedouw Reference Swyngedouw2005, Nikolakis et al. Reference Nikolakis, Grafton and To2013, Jackson Reference Jackson2015). Hall (Reference Hall2014), Syme et al. (Reference Syme, Nancarrow and McCreddin1999) and Parrack (Reference Parrack2010) found generally that more than market mechanisms are required for a fair and just allocation policy. The cluster of studies in the 1980s and 1990s consistently highlighted the inadequacy of addressing various community values purely through the use of market instruments (Syme et al. Reference Syme, Nancarrow and McCreddin1999).

Jackson (Reference Jackson2019) explored how legitimacy might be achieved in a society divided by colonial relations of power. Power sharing is vital not only in water policy, but also in recognizing multiple knowledge practices. Viewing environmental water through the lens of settler-colonial theory emphasizes the assumption that when the colonizer arrived, no one ‘owned’ the water, so they could therefore pass laws to govern it (see Marshall Reference Marshall2017). This is further compounded by ongoing impacts of colonial histories and Western epistemologies of environmental water, which rely on technocratic paradigms of framing environmental water needs in purely hydrological terms (Jackson Reference Jackson2015, Moggridge & Thompson Reference Moggridge and Thompson2021). Jackson (Reference Jackson2015) called for water decision-makers to alter their current approach so as to avoid utilitarian values trumping relational ones. Therefore, many of the legitimacy issues surrounding environmental water stem from programme objectives and the methods used to address these objectives, including expert opinions that do not reflect community values (Kosovac Reference Kosovac2022, Mussehl et al. Reference Mussehl, Horne, Webb and Poff2022).

The power of values and community perceptions of environmental risk

This review identified two key findings that strongly influence environmental water across all groups: (1) personal values have tended to determine the acceptance of allocation of environmental water (Syme et al. Reference Syme, Nancarrow and McCreddin1999, Parrack Reference Parrack2010, Bjornlund et al. Reference Bjornlund, Zuo, Parrack, Wheeler and De Loë2011, Lane-Miller et al. Reference Lane-Miller, Wheeler, Bjornlund and Connor2013, Mendham & Curtis Reference Mendham and Curtis2018, Conroy et al. Reference Conroy, Knight, Wassens and Allan2019, Wineland et al. Reference Wineland, Fovargue, York, Lynch, Paukert and Neeson2021); and (2) willingness to support or give up water allocations has been highly dependent on perceptions of risk to the environment (Graham Reference Graham2009, Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, Zuo and Bjornlund2014, Mott Lacroix et al. Reference Mott Lacroix, Xiu and Megdal2016).

These two issues – values and risk – combine to shape community perceptions of and responses to environmental water. Personal values refer to the individual values of each being (Sagiv et al. Reference Sagiv, Roccas, Cieciuch and Schwartz2017) that are positioned to consider the environment, community, personal responsibility, safety or even the role of the government and markets.

Decisions around environmental water will hinge on the value system and objectives of stakeholders that often conflict with one another, prompting the decision-maker to establish a hierarchy of value preferences.

Much of the environmental water movement has been driven by the physical sciences and subsequently has filtered through to the objectives set for environmental water (O’Donnell & Talbot-Jones Reference O’Donnell and Talbot-Jones2018). These science-based objectives are not necessarily readily interpreted by stakeholders to link to what they perceive as valuable about a river and its ecosystem. Indeed, the public perception of river health largely stems from aesthetic features (Tarannum et al. Reference Tarannum, Kansal and Sharma2018, Flotemersch & Aho Reference Flotemersch and Aho2021, Mumbi & Watanabe Reference Mumbi and Watanabe2020) or cultural and religious beliefs (Lokgariwar et al. Reference Lokgariwar, Chopra, Smakhtin, Bharati and O’Keeffe2014), which may not necessarily reflect hydrological and ecological river health data. This dissonance between what is reported and what is publicly valued can create the public distrust in data previously reported.

There are regular calls to identify how much water the environment needs at any time (Lukasiewicz & Dare Reference Lukasiewicz and Dare2016). Lukasiewicz et al. (Reference Lukasiewicz, Syme, Bowmer and Davidson2013) and Syme et al. (Reference Syme, Nancarrow and McCreddin1999) highlighted the government’s characterization of the environment through a quote from one participant: ‘[T]he environment has to justify every single drop of water it uses … whereas the same hurdles aren’t placed on the irrigators’ (Lukasiewicz et al. Reference Lukasiewicz, Syme, Bowmer and Davidson2013, p. 248). Respondents in one study expressed a desire to see the impacts of environmental water and to ensure that it is used efficiently: ‘The lack of directly observable outcomes can create cynicism’ (Lukasiewicz & Dare Reference Lukasiewicz and Dare2016, p. 190). This call to justify the use and efficiency of environmental water poses a number of challenges. Firstly, the quantity of water required links back to value judgements regarding the type of aquatic life that should be bolstered and the riparian environment that should be helped (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Hatton Macdonald and Bark2019). Secondly, ecosystems and hydrology are highly variable systems, and predicting ecosystem responses – particularly based on a comparison to a ‘no environmental flows’ scenario – is fraught and full of uncertainties. The response times are also not immediate but may take decades to be realized. Monitoring programmes are often established with a dual purpose of improving ecological knowledge and simultaneously providing justification to the broader public for the funding of environmental water.

In considering the general public’s perceptions of environmental water, existing studies report on the lack of firm or rigid beliefs about environmental water (Mendham & Curtis Reference Mendham and Curtis2018). This is in line with the lack of knowledge and understanding of what environment water is (Loo et al. Reference Loo, Penko and Carpenter2018, Murray–Darling Basin Authority & Orima Research 2021). Those that do have knowledge of environmental water often have pro-environmental values or engage often with their natural surroundings and subsequently are more likely to be supportive of environmental water allocations (Mott Lacroix et al. Reference Mott Lacroix, Xiu and Megdal2016).

Economic arguments tended to come up less in the general public’s perceptions of environmental water compared to, for example, those of irrigators (Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, Zuo and Bjornlund2014). The economic framing of environmental water in studies with irrigators highlighted a distinct link between productive value and the price of water. In locations that have water trading markets, the inherent underlying assumption is that those that can pay for the high prices of water are more likely to experience greater economically productive use of the water (Alexandra & Rickards Reference Alexandra and Rickards2021).

The importance and economic value of environmental water to irrigators are directly linked to the prevalence of drought conditions (Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, Zuo and Bjornlund2014, Loo et al. Reference Loo, Penko and Carpenter2018). Although many studies reflected the importance of values in public perceptions of environmental water (Hall Reference Hall2014, Syme et al. Reference Syme, Nancarrow and McCreddin1999), this had mixed results when considering irrigator perspectives (e.g., Lane-Miller et al. Reference Lane-Miller, Wheeler, Bjornlund and Connor2013). Unlike studies on public viewpoints, findings on irrigator perspectives seem to highlight a larger distrust of science and governments in general in the management of environmental water. This view influences the way in which environmental water is framed and perceived, in particular with regard to its benefits (Graham Reference Graham2009).

Those working in government roles related to managing water have framed environmental water in a starkly differing fashion from that of the general public, whose views have often revolved around the enjoyment of rivers (Mendham & Curtis Reference Mendham and Curtis2018, Wineland et al. Reference Wineland, Fovargue, York, Lynch, Paukert and Neeson2021). As discussed, government water practitioners often saw themselves as custodians and protectors of the rivers while simultaneously framing themselves as another ‘irrigator’ in the system (a nod to the ‘productive’ use of water). Arguably, this can be seen as subliminal framing directed at irrigators in the attempt to position environmental water as a productive and efficient use of the resource. The current government approach of stewardship over waterways and its management is wholly incongruent with Indigenous understandings of environmental water, which link the importance of cultural and social aspects of water together with ecological indicators (Jackson Reference Jackson2015, Reference Jackson, Horne, Webb, Stewardson, Richter and Acreman2017, Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Bark, Garrick and Pollino2015, Conroy et al. Reference Conroy, Knight, Wassens and Allan2019).

Conclusion

Understanding the perspectives of varied stakeholders within environmental water remains essential to the ongoing management of water resources, whether this be in rural or urban spaces (Kosovac et al. Reference Kosovac, Davidson, Malano and Cook2017a, Reference Kosovac, Hurlimann and Davidson2017b). Although limited in number, the studies that have been highlighted throughout this paper provide an important acknowledgement of the current state of knowledge regarding community perceptions of environmental water.

Our analysis confirms the finding of Brewer et al. (Reference Brewer, McManamay, Miller, Mollenhauer, Worthington and Arsuffi2016) that there is an persistent gap in terms of research into perceptions of environmental water globally. There is an opportunity to explore sentiment towards ‘water for the environment’ principles in different contexts, as this is under-researched and could provide the impetus for future action in protecting ecosystems. In this review, we also highlight a number of notable gaps and limitations in the current scholarship on this issue:

-

o The majority of empirical studies focus on the general public, with little empirical exploration of government decision-makers.

-

o Cultural water and environmental water are often conflated, making it difficult for policymakers to fully grasp the requirements in the area, thus continuing to exclude and deny the interests of Indigenous peoples.

-

o The locations of the studies are highly constrained, with the vast majority being undertaken in Australia, Canada or the USA. Environmental water is a global phenomenon, and scholarship that examines community perceptions of environmental water requires a much broader geographical scope.

-

o The studies have predominantly been undertaken in a water market context where the water is separated from land rights in order to be bought and sold. This places environmental water in a context in which it is given monetary value, which could serve to skew societal perceptions of its value in comparison to situations in which it is not commodified.

The views and values of stakeholders are critical to the management of any socio-ecological system. However, to date, community perceptions of environmental water represent an area of scholarship that is limited geographically to a small number of countries, predominantly Australia. We would expect that the number of articles addressing this topic will continue to rise as a result of increasing politicization of water issues and ongoing interest in participative decision-making. A continued proliferation of studies in this field presents a pathway to understanding and building support for global environmental water programmes, a welcome move for the future of environmental sustainability.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892923000036.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

AK and ACH are funded through ARC DECRA award DE180100550. EO’D is funded through the Melbourne Law School Early Career Academic Fellowship.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

None.