This chapter analyses the find story attached to the discovery of the Nag Hammadi texts, a topic of much scholarly debate of late. Some of the early researchers engaged with the elucidation of the texts’ discovery have been accused of Orientalism, which has ultimately begun to affect the way the texts’ ancient background and use has been interpreted. In this chapter the find story is revisited, and it is argued that the accusations of earlier scholars’ Orientalism are exaggerated; furthermore, this is a much less problematic aspect of Nag Hammadi scholarship than the contemporary romanticisation of Gnosticism.

Following the Evidence

Recently, a new and much welcomed perspective has developed within the field of early Christian materiality. Several large projects are currently focused on tracing the modern history of ancient manuscripts with the aim of investigating the question of how best to deal with those appearing on the black market without a clear archaeological provenance.Footnote 1 Brent Nongbri, one of the pioneers of this new perspective, highlights the importance of being aware of the modern history of the manuscripts we study in order to avoid labouring under preconceived notions when pursuing their ancient contextsFootnote 2 – a precept I follow here.

Since very few ancient texts are discovered or exhumed by professional archaeologists, with most turning up on the black market in antiquities, it is worthwhile retracing the steps of a manuscript’s discovery and trying to ascertain the details surrounding it; finding the discovery site can, understandably, provide clues to the historical background of a text. There are, however, several circumstances that face anyone who ventures to establish the facts surrounding an ancient text’s modern discovery. Nongbri sums up the difficulties as follows:

[There are] several reasons why the exact details of a discovery of ancient books can be very difficult to reconstruct after the fact: Finds of books can be divided almost immediately upon discovery and dispersed among those present. Books can be further subdivided by intermediaries. News of a discovery can quickly attract antiquities dealers from out of town who can purchase and further scatter parts of a find while at the same time mixing the materials from the new discovery with their existing inventories. The fear of confiscation by the government can lead to the suppression of accurate information and the production of false stories.Footnote 3

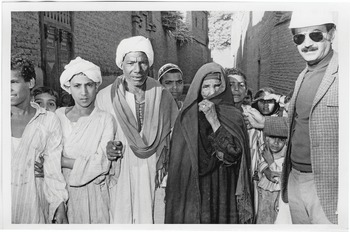

Enormous efforts have been made to retrace the steps of the Nag Hammadi texts’ discovery and how they ended up on Cairo’s black market for ancient artefacts in 1945. Ultimately, although the texts’ likely discovery site has been narrowed down to the general area adjacent to the southern Egyptian town that has given the text collection its modern name, we will probably never be sure of the exact circumstances in which they were found or even if all of the books that were discovered have yet been accounted for (see Fig. 2.1). Many different stories have been told by the people supposedly involved in the discovery (see Fig. 2.2). Even the fellah at the centre of the story, Muhammad Ali al-Samman, has provided varying versions at different times: the codices were found when digging for sabkha (fertiliser), in a jar, next to a body, behind a rock, in a tomb, in a cave. Was Muhammad Ali al-Samman alone, or accompanied by fellow camel drivers? Exactly where was the discovery made? How many books were found and what happened to them after the discovery?

Figure 2.1 Scenic shot of desert lake oasis with Jabal al-Ṭarif cliff in background. Buildings can be seen against the backdrop of the mountains.

The scholar first on scene to investigate the context of the finding was Jean Doresse, who travelled to Upper Egypt several times at the end of the 1940s and was told by his local guide that the texts were found hidden in a large earthenware jar by peasants digging for fertiliser. They were then sold to traders who took them onward to Cairo. Doresse had also been told that some of the texts, or parts of them, might have been destroyed by the peasants, who supposedly used them to kindle a fire. What is more, he learned that some of the protagonists had been involved in a revenge killing in close proximity to the time of the discovery.Footnote 4 Years later, in the 1970s, James Robinson – director of the international translation team that subsequently presented the first modern editions of the texts – visited the site in order to find out more. He made repeated efforts to locate the find site, interview witnesses and backtrack the codices’ steps to the black market, retrieving many details which Doresse had omitted or failed to uncover.

Robinson’s efforts were fruitful as he found the person who was said to have made the discovery, Muhammad Ali al-Samman. In one of the first versions of the find story he published, Robinson tells us that al-Samman discovered a large jar while out digging for fertiliser.Footnote 5 Afraid that a jinni might be hiding inside it, he hesitated until, consumed by curiosity and the hope that it might contain gold, he finally broke it open, only to find old books. Disappointed, he took the books home and threw them in the courtyard, where his mother subsequently found them and used some of the papyrus to kindle a fire. He then forgot the books for a while because he was tangled up in a family feud, Robinson was told. Al-Samman’s father had been murdered some time before and the alleged perpetrator, a man from a rival clan named Ahmed Isma’il, had disappeared, only to resurface around the time of the discovery. When al-Samman found out that his enemy was back, he took action and killed the man in revenge for his father’s death and was placed in jail. Upon his release he returned home, found the books still in the courtyard where he had left them and subsequently sold them on.Footnote 6

While some scholars have successfully deconstructed the reports conveyed by Muhammad Ali al-Samman, via Robinson, and included them in the scholarship about the text – strengthening parts of the story with new evidence while disregarding other less credible aspectsFootnote 7 – others have questioned the credibility and thoroughness of Robinson’s reports of his ventures in Egypt, arguing that the find story should be altogether disregarded as evidence for the background of the texts.Footnote 8 It is true that Robinson’s accounts of his many and long explorations in Egypt are not without fault. Details of the find story have varied over the years, without a clear statement of the reasons for the changes (even if they were justified).Footnote 9 Moreover, some scholars have recently accused Robinson of Orientalism, viewing his version of the find story – one that gained wide notoriety through Elaine Pagels’ popular book The Gnostic Gospels, where it was retold – as a disturbing Western narrative full of prejudice. Mark Goodacre has presented the following analysis:Footnote 10

It is a fantastic story, irresistible for introducing these amazing and important discoveries. The bloodthirsty, illiterate peasants happen upon an amazing find while out looking for fertilizer. They worry about genies but lust for gold, they have no inkling of the magnitude of their find, and their mother is as stupid as she is callous, burning valuable documents and then encouraging her sons to use the very mattocks that had broken open the earthenware jar now to murder a man. The narrative scarcely hides its moral, that important artefacts like this need to be wrested from the hands of those who cannot hope to understand them, and placed in the hands of responsible, Western academics.Footnote 11

Goodacre is not alone in levelling criticism at Robinson. Nicola Denzey Lewis and Justine Ariel Blount also viewed Robinson’s story as Orientalist, maintaining that the texts were not found near the slopes of Hamra Dun, outside the modern city of Nag Hammadi, as Robinson’s initial reports conveyed. Instead, they suggest that the books were found in graves because they were actually ‘books of the dead’ meant to guide the soul of the deceased to heaven. This hypothesis has gained few supporters. The article in which this position is advanced takes its departure in debunking previous interpretations of the find story and harshly critiques Robinson’s story and all those who have promoted it. We should be ashamed of ourselves, they write, even to consider that people could act in the manner Robinson suggests for Muhammad Ali al-Samman. They go on to add, ‘The narrative is a fine one for classroom telling, but it works less and less effectively as we become more sensitised to our own Western prejudices and assumptions. Egyptian peasants do not fear jinni in bottles or rip out each other’s hearts and eat them on the spot – and shame on us for believing, even for a moment, that they do.’Footnote 12 Denzey Lewis, Blount and Goodacre argue that the description of Muhammad Ali al-Samman in Robinson’s version of the find story mirrors how prototypical Oriental ‘Others’ are often portrayed by Occidental colonialists: murderous, superstitious and greedy. The story attached to the texts’ discovery only solidifies Western prejudices about the East as ignorant and immoral, unlike the civilised, rational and humane West.Footnote 13

There are indeed aspects of Robinson’s reports of the events that one should be careful about accepting without qualification. Goodacre criticises Robinson for not employing the interview techniques that one would expect of an anthropologist and being less than transparent about the discrepancies in the find story he was told on different occasions. What is more, as mentioned above, he has presented different versions of the story without being clear which he favours and why. As Nongbri notes, the critique could have been avoided if Robinson had been more straightforward about his own doubts as, he too had reservations as to the validity of the find story, given the various versions he had been told.Footnote 14 Nevertheless, it is my view that the accusations of Orientalism are ultimately unreasonable.Footnote 15

I argue – and here I follow Nongbri and BurnsFootnote 16 – that Robinson was painstakingly meticulous and critical in tracing the books’ provenance. Muhammad Ali al-Samman was, for example, not able to identify the exact location where he found the texts, and changed his story at times about the details of the find, which is why Robinson conducted excavations at several sites. Despite these efforts, uncertainty about the precise location of the actual find site is not denied: ‘the excavation produced no archaeological confirmation of the precise site of the discovery’, Robinson states.Footnote 17 In a monumental two-volume work, Robinson retraces the steps he took and those taken by his predecessors, an invaluable resource for those of us interested in the texts’ modern and ancient background.Footnote 18 Robinson’s many years on the ground in Egypt should be applauded – few scholars of antiquity ever undertake such ventures – and I am unable to find any indications suggesting that he viewed and treated his Egyptian informants with anything but respect and recognition of their dignity. But intentions aside, is it still not Orientalism?

Goodacre’s and Denzey Lewis and Blount’s critiques of Robinson’s findings are attempts to apply to Nag Hammadi scholarship the many valuable lessons post-colonial theory has taught us about the violent and intrusive effect Western dominance has had on the lives of the Other. It is undeniable that the high price ancient texts command on the black market – the result of Western demand – has led to the unfortunate situation we see in Egypt and other places around the world, where looting of such artefacts is much too common. This leads to grey areas in the find stories (which also record a crime), as well as the mishandling and sometimes destruction of invaluable historical objects. It is indeed difficult to know whether one should criminalise the buying of ancient artefacts that are not from sanctioned digs, a course of action which poses the risk that those that have been dug up in suspicious circumstances and consequently remain unsold will be forever lost, deposited on the back shelf of some black market dealer’s shady inventory.

Pioneers in post-colonialism, like Edward Said, have contributed a great deal to our awareness of the way we reify the Other, and, like most dynamic fields of research, even post-colonial perspectives have improved of late. For example, as pointed out by Richard King, the importance of indigenous peoples’ portrayal of themselves to others must be recognised when discussing views of the ‘East’ in the ‘West’. Let us take the category ‘Hinduism’ as an example. Said argued that this was an empty category forced upon a multitude of Indian religions by lazy Western scholars and British administrators in their efforts to assert control over what they did not understand. The efforts made by Indians themselves in adopting and implementing the category are ignored, missing the fact that many Indians could appreciate the benefits of having an umbrella term for the diverse religious practices on the subcontinent, which ultimately aided in the unification of its people against British dominance. It is not necessarily an expression of oppression if a people adopts categories and terminology that have been invented by outsiders. In fact, that is the way new categories are often conceived. Indeed, this is how the term ‘Christian’ was first constructed, coined by outsiders and only later adopted by Jesus-followers themselves.Footnote 19 As Jean-Paul Sartre famously argued: becoming aware of the gaze of others is the first step toward becoming aware of our own subjectivity.Footnote 20

By ignoring the agency of the Other (yet again!), we risk ending up with a one-sided view of history.Footnote 21 I argue that some of this narrowness of vision is reflected in the critique Goodacre, Denzey Lewis and Blount have levelled at Robinson, as well as indirectly by those who have disseminated his version of the Nag Hammadi discovery uncritically (including myself!). The unreasonableness of their accusations becomes evident in light of a four-part drama documentary called Gnostics, aired in 1987 on Channel 4 (UK). The Border TV production, written by Tobias Churton,Footnote 22 offers the viewer basic information on so-called Gnostic literature, and the Nag Hammadi discovery is one of the central plots in Episode 1: ‘Knowledge of the Heart’. A number of prominent scholars appear in the film, including Hans Jonas, Gilles Quispel, Elaine Pagels and James Robinson, and the viewer is invited to follow Gilles Quispel on an expedition to the village in Egypt near where the discovery of the codices was said to have been made. Quispel meets and thanks Muhammad Ali al-Samman himself for his efforts in bringing the texts to the world’s attention. What follows is a short interview with Muhammad Ali al-Samman where he gets to tell the story, again; it is a word-for-word account of al-Samman’s appearance in the documentary, as translated by the interpreter employed by Border TV productions:Footnote 23

Muhammad Ali al-Samman: I was digging for sabkha, for fertiliser, with my pick axe, and carrying it back to the fields on the camel. Then I came across this big earthenware pot which was buried in the sand. I had a feeling that there might be something inside.

The interview breaks off and a conversation with Robinson is inserted to give additional information on Muhammad Ali al-Samman. Robinson says the following: He is from the al-Samman clan, which dominates many of the villages in that part. He was – is a peasant, illiterate, a Muslim. Worked as a camel driver for a middle-class Copt. And in his generation it was typical, the Copts were the white collars and the Muslims were the physical laborers.

The film cuts into Muhammad Ali al-Samman again and the story continues: I came back later the same day and I smashed the pot open. I broke it open exactly where I had found it. I thought there might be an evil spirit inside, a jinni. I had never seen anything like it before. I smashed the pot on my own and inside I found these books, then I brought the others over to see. They said: ‘We don’t want anything to do with these books, they belong to the Christians, the Copts.’ They said, ‘It’s nothing to do with us.’

Robinson is cut into the picture again and while the documentary films the courtyard and house of Muhammad Ali al-Samman, Robinson tells the story of how the books were brought back and some of them were burned. Again Muhammad Ali al-Samman is brought back to the scene and he is asked about this fact, and answers: It was all just rubbish to us. Yes, my mother did burn some, in the bread oven.

After being presented with a publication containing his picture, Muhammad Ali al-Samman continues the story: One of the people of the village of Hamre dun killed my father, so it was decided that I should kill his murderer, and revenge. I did kill him, and with my knife I cut out his heart and ate it. I was in jail because of the killing, and when I got out of jail I found that my mother had burned a lot of those old papers. Later on I sold one book, all the others had gone. I got eleven Egyptian pounds for it.

He is then asked by Quispel if he had any regrets about what happed when he found the books. No, I don’t care. I don’t give a damn about them! It does not even enter my head to think about it.Footnote 24

Here Muhammad Ali al-Samman recounts a version of the find story that includes many of the details that Goodacre, Denzey Lewis and Blount have presented as unbelievable inventions and exaggerations by Orientalist Western scholars. The ambition to avoid colonial prejudices can only really be fulfilled if we contextualise the object of study, letting the Other appear on its own terms – by applying a Geertzian ‘thick description’Footnote 25 or through an alterity as suggested by LevinasFootnote 26 – rather than rejecting portrayals of foreign cultural practices as unbelievable or narrow-minded because they do not fit our view of moral or ‘rational’ behaviour.

Let us try to approach the find story from what we actually know of the cultural milieu with which we are dealing. Firstly, believing in jinn is – contrary to what Denzey Lewis and Blount seem to believe – widespread in rural Egypt and not a colonialist invention. Secondly, retaliating for perceived wrongdoings aimed at your family/clan is also quite understandable, a righteous act in shame–honour societies such as those in rural Egypt.Footnote 27 Nonetheless, there are aspects here that problematise the story of murder, but not for Orientalist reasons. There are no records of Muhammad Ali al-Samman’s having been officially accused of murder or convicted of the crime. If he committed the murder, as he claims, in the eyes of the law he would have been sentenced to a minimum of twenty-five years in prison, and not released shortly after the event, as he also claims. But this does not mean it did not take place. Assuming Muhammad Ali al-Samman’s clan and that of the murdered man followed the social patterns portrayed in anthropological studies of the area, there are scenarios which would have let al-Samman evade the authorities.Footnote 28 If the two families resolved the issue among themselves through the law of custom (ʿurf), the authorities could have been left out of the arrangement. If possible, dealing with the authorities is generally avoided for a multitude of reasons, including corruption, draconian police treatment, the uncertainty of outcome and the time-consuming nature of the bureaucracy.Footnote 29 If a death or killing takes place, one can seek to resolve the issue by asking the victim’s family for forgiveness or requesting the aid of a so-called reconciliation assembly. These complicated processes involve a number of mediators and arbitrators. However, if a solution had been reached through a reconciliation assembly, one would not expect the party asking for forgiveness to act as Muhammad Ali al-Samman does in the interview, proudly and without remorse – even describing the act itself (and possibly grossly exaggerating it). He would have been expected to show remorse or at least humility. Furthermore, if the conflict had been resolved, Muhammad Ali al-Samman would probably have avoided dwelling on something that would risk reawakening a reconciled conflict and would not, in detail and with exaggerated wording, have described the act which had been resolved/forgiven. With these factors in mind, one can surmise that the conflict between Muhammad Ali al-Samman and the rival family was ongoing when Guilles Quispel met Muhammad Ali al-Samman in 1986. And if this were the case, Muhammad Ali al-Samman would have felt honour bound to cause harm to the other family and its reputation at any given opportunity. Thus, we should treat any information he provides about the incident with marked scepticism. Nevertheless, it is not Orientalism to take him at his word, as killings of the nature he describes (although the gruesome detail could well have been added to enhance his machismo) are anything but uncommon in family feuds.

Gnosticism and the Mystic East

While I am of the opinion that Goodacre’s and Denzey Lewis and Blount’s critique of Robinson’s find story goes too far, there are some scholars who have gone even further. Maia Kotrosits, for example, writes that the find story connected to the Nag Hammadi texts ‘represents and perpetuates the Orientalist epistemological tropes that have since been fixed onto the individual texts themselves’.Footnote 30 This is a bold statement and, if applied too generally, it is also problematic. Unfortunately, Kotrosits does not provide detailed discussion of the erroneous interpretations of the individual Nag Hammadi texts which she claims would be the result of Orientalism. And in my opinion there is little that supports the view that the find story has much to do with subjection of the texts themselves to Orientalising interpretations.Footnote 31 We cannot ignore decades of studies of the mechanisms behind constructions of orthodoxy vis-à-vis heterodoxy, nor what we know about the heresiological genre.Footnote 32 The early Christian authors who disqualified the forms of Christianity represented in the Nag Hammadi texts – judgements which influenced modern perceptions of the Christian/Gnostic dichotomy that have informed theologians since the end of the seventeenth century – did not do so on Orientalist grounds. Anachronisms of this kind would be an unfortunate result of post-colonial theory being applied inaccurately.

Although we should avoid generalising about the mechanisms of Orientalism, Kotrosits has a point, nevertheless. There have indeed been aspects of romanticisation that have impacted on the Nag Hammadi texts, but I argue that this has to do with the texts being attached to the notion of Gnosticism, rather than the story of the texts’ discovery. As Dylan Burns has argued, the Nag Hammadi texts have been interpreted as containing ‘Eastern’ wisdom, more similar to Buddhism or Hindu philosophy than contemporary Christianity.Footnote 33 From this perspective, then, interpretations of the texts have been coloured by Orientalist preconceptions. Burns also calls attention to the fact that one can find what he calls ‘auto-Orientalising’ tendencies in the texts themselves; that is, they appropriate images of Egypt or other Eastern contexts or traditions as places of spiritual knowledge that is of greater purity than the much younger Hellenic wisdom (Zostrianos being just one example of a text that legitimises its content by attaching it to the ancient Persian sage Zoroaster).

I would argue that the form of Eastern religion that the Nag Hammadi texts have been thought to represent, since they are understood to be representing ‘Gnosticism’, is not Eastern religion per se but, rather, contemporary views of Eastern religion invented to fit a Western context. Take Buddhism, for example. When exported to the West, Buddhism was packaged for a Western audience in the religious language of Christianity.Footnote 34 Furthermore, it was not just any Buddhism that was exported, it was an intellectual, elite version, one that put more emphasis on introspection, text reading and meditation than practice, belief in spirits and ‘unreflective’ ritual activity. If the Nag Hammadi texts have been exposed to Orientalist preconceptions that determine how they are read, it is in a form that I would call ‘backdoor Orientalism’. Gnosticism and the Nag Hammadi texts have not been likened to Eastern religions so much as Westernised versions of Eastern religions, and they have not been represented as containing hidden wisdom because they were found in the East (Egypt), but because they have been associated with heresy, subversion and counter-culture. Ironically, the ‘backdoor Orientalism’ to which the Nag Hammadi collection has been subjected is attached to the very same mechanisms that produced critical theories such as post-colonialism. The discovery of the Nag Hammadi codices coincided with a religious awakening in the West, particularly in America, with Indian gurus touring the West and famous popstars and intellectuals visiting the East. In popular culture, the East was associated with an ancient form of wisdom that represented all the ideals that the beatnik generation and the subsequent Flower Power era stood for: free love, pacifism, spirituality, contemplation, introspection and the attainment of higher truths and knowledge, as well as gender equality.Footnote 35

Thus, the Orientalism that has coloured modern conceptions of the Nag Hammadi texts has not much to do with the find story, as Kotrosits, Goodacre, Denzey Lewis and Blount would have it. There is something much more complex going on, which has to do with the texts’ association with heresy and counter-culture. Owing to their often-misdirected association with the esoteric and subversive, the texts have been interpreted in erroneous ways. The New Age generations were the intellectual heirs of the occult milieux and social movements taking form in Europe from the nineteenth century, while reception of the Askew codex in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries exemplifies mechanisms similar to the biases applied to the Nag Hammadi texts. The Askew codex was received as the Gnostic Bible and – although it did not fit squarely with how the Church Fathers had described the ‘Gnostic’ – it was made to represent the anti-establishment ideas popular at the time of its discovery.Footnote 36

There are, of course, points where Orientalist preconceptions intersect with counter-cultural ones; the fact that the East was considered mystical and dangerous is surely one of the reasons many famous occultists were drawn to China, India and the Middle East.Footnote 37 While modern interpretations of the texts are of less importance in this study than the Nag Hammadi codices’ antique context – and what we can learn of it by engaging with the codices’ material features – the post-colonial perspectives Burns regards as ‘auto-Orientalisation’ tendencies cannot be neglected in this regard.

Conclusion

The rest of this book is devoted to the material aspects of the Nag Hammadi texts. In light of this and the previous chapter, the methodological and theoretical perspectives that inform the study as a whole should, hopefully, have become more transparent. As we have seen, in their efforts to approach the Nag Hammadi texts without the preconceived notions attached to Western prejudices against the Eastern Other, some scholars have gone too far and rejected the find story altogether and, thus, been able to present alternative interpretations of the texts’ ancient uses. The texts have certainly been romanticised and – by way of the concept Gnosticism – been attached to preconceived notions regarding the existence of a spiritual knowledge that has been passed down in an unbroken chain since antiquity. As such, the texts are still subjected to Orientalising interpretations, being portrayed by some as speculative and less genuine than ‘pure Christianity’ or ‘pure philosophy’, while others elevate them on the basis that they contain pure and unmitigated spiritual truths with which people of the West have lost touch. Thus, the reception of the Nag Hammadi texts follows well-known patterns familiar from the ways that Eastern religions have been received in the West since the nineteenth century.