Introduction

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) caused by Staphylococcus aureus exceed 50 cases/100,000 population, even in high-resource countries, with a mortality rate approximating 20%–30%. Reference van Hal, Jensen, Vaska, Espedido, Paterson and Gosbell1 Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) adds an even greater impact through higher 30-day and in-hospital mortality rates. Reference Blot, Vandewoude, Hoste and Colardyn2 The burden of BSIs caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is not just restricted to patient outcomes. Reference Cassini, Högberg and Plachouras3 MRSA BSIs account for more than 250,000 extra bed days (BDs) in countries of the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA). Reference de Kraker, Davey and Grundmann4 Several regions have reported an apparent reduction in MRSA proportions from blood culture S. aureus isolates. 5 However, despite a significant reduction in resistance proportions, Cassini et al. estimated that the incidence of MRSA BSIs in the EU/EEA actually increased by 1.28 times between 2007 and 2015. Reference Cassini, Högberg and Plachouras3 MRSA bacteremia therefore remains an important medical challenge which demands effective efforts at prevention and control.

Setting

Mater Dei Hospital (MDH) is the sole tertiary care hospital in Malta, a Mediterranean island with a population of approximately 500,000. This 1000-bed facility provides various specialist services, including intensive care, transplantation, and complex surgery. Not surprisingly, it is the main contributor to the country’s AMR epidemiology. For the best part of the 1990s and 2000s, infections caused by MRSA were hyper-prevalent. In 2008, Davey et al identified Malta as having the second highest incidence of MRSA bacteremia in the EU/EAA. Reference Davey, Sneddon and Nathwani6 We outline sequential interventions to address this challenge in the subsequent decade. For the purpose of this publication, a case of healthcare-associated MRSA bacteremia (HA-MRSA-B) was defined as an MRSA isolate grown from a blood culture taken 48 hours or later after admission to hospital or preceded by an intervention in the previous 30 days (such as surgery or hemodialysis).

Interventions

Hand hygiene campaign

Surveillance data on MRSA bacteremia, following participation in EU/EEA surveillance networks, elicited a previously absent sense of urgency to address the problem. This coincided with the launch of the World Health Organization’s “Clean Care is Safer Care” Global Patient Safety initiative, promoting improved hand hygiene (HH) through increased alcohol hand rub (AHR) use at critical moments of patient contact. Reference Pittet, Allegranzi, Storr and Donaldson7 A HH campaign was launched in 2008 and has been described elsewhere. Reference Abela and Borg8 It focused heavily on extensive audits of HH compliance and monitoring of AHR use, which we have previously shown to correlate well with assessment of HH performance through visual observations at MDH. Reference Borg and Brincat9

Root cause analysis

At around this time, the successful efforts of the United Kingdom to address its hitherto high MRSA prevalence were being highlighted. Reference Duerden, Fry, Johnson and Wilcox10 A cornerstone of this initiative was the requirement to perform a root cause analysis (RCA) for each case of HA-MRSA-B, conducted by the patient’s clinical team. The protocol required early gathering of data to find out what happened, generating an action plan to address the key issues identified and the implementation and monitoring of an action plan which would feed learning into an organization’s governance to help reduce the chances of a repetition. 11 In 2010, an attempt was made to leverage positive deviance from this experience and implement a similar approach in MDH. However, initial experiments to replicate the UK administrative model were unsuccessful, primarily due to lack of ownership by front-line professionals. RCAs only materialized when the hospital’s Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) team took over their full management. IPC performs the preliminary review of the case and invites all the key stakeholders involved in the patient’s care to a meeting, led by the IPC Lead. The clinical team provides the background which is then followed by a discussion, asking the “five why’s?” to identify possible factors. Reference Venier12 Every effort is made to ensure that the meeting takes place in a safe, non-punitive environment and that everyone can provide their input, keeping the focus on the event and related processes. At the end of the meeting, based on RCA conclusions, action items are agreed and minuted. The minutes and corrective actions are sent to all meeting participants and copied to senior management. The IPC team reviews implementation of agreed corrective actions and raises any identified lack of progress with senior hospital management.

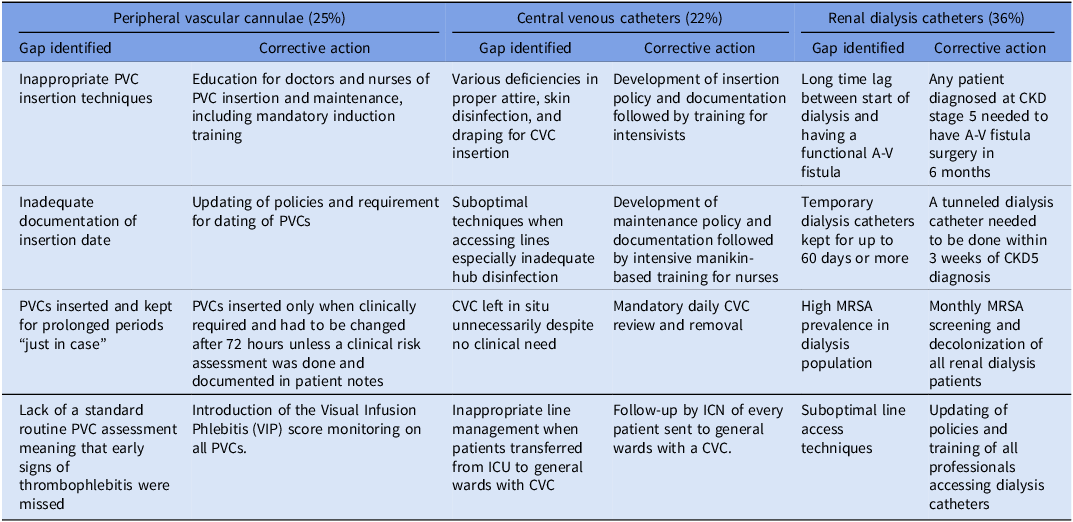

An assessment of the RCAs held in 2011, the first full year of the initiative, showed that the absolute majority of cases were attributed to intravenous (IV) devices. Most were linked to renal dialysis (36%) where almost all patients had had a non-tunneled double-lumen hemodialysis catheter (NTDLHC) at the time of the HA-MRSA-B. A further 25% of HA-MRSA-B were linked to peripheral vascular cannulas (PVC) and 22% to central venous catheters (CVC). In practically all of these RCAs, clear practice gaps were identified and evidence-based corrective actions instituted hospital-wide (Table 1).

Table 1. Main factors identified from root cause analysis (RCA) reviews held in 2011 and corrective actions implemented.

Intravenous device interventions

The corrective actions included a mixture of policy development/updating, education and training, positive and negative motivators as well as—essentially—system change. In renal dialysis, targets were established to reduce the lag period from the start of dialysis until arterio-venous fistula surgery. NTDLHCs were only allowed as an emergency interim measure for no longer than 3 weeks. Within this period, and in all elective cases, a cuffed tunneled line needed to be inserted for hemodialysis. Reference Gallieni, Brenna, Brunini, Mezzina, Pasho and Giordano13 Whereas 30.1% of patients on hemodialysis had a NTDLHC in March 2011, this reduced to 0.5% in March 2017, despite a 64% increase in the hemodialysis population during the same period. This major change was only possible following the engagement of two specialist radiologists with experience in such insertions. Maintenance of dialysis lines was also improved through adoption of dressings with higher moisture vapor transmission rates (MVTR) and training of nurses in care bundles.

The Visual Infusion Phlebitis (VIP) score became a required mandatory daily assessment for each patient with a PVC. Reference Morris and Heong Tay14 This policy modification was only possible after another system change: the introduction of PVC dressings with transparent visibility windows. The implementation of a 72-hour cutoff for PVC duration was more contentious, since publications at the time had shed doubt on its effectiveness. Reference Rickard, McCann, Munnings and McGrail15 Nevertheless, it was determined that the level of PVC monitoring and care in the centers where the studies were held, had not yet been achieved in MDH; therefore the literature could not necessarily be transposed to the hospital situation. CVC initiatives mirrored the recommendations of the Institute of Health Improvement and were based heavily on the work of Berenholtz et al. Reference Berenholtz, Pronovost and Lipsett16 They were however modified to reflect local culture. In particular, ICU nurses raised objections to supervising intensivists during insertion and, even more, to stopping the procedure if they noted any deviations from operating procedures; neither was adopted. In addition, the checklists were used more as an aide memoire than the more stringent application in the reference publication.

Universal MRSA admission screening

The third key intervention was introduced in 2014 with the commencement of universal MRSA admission screening for practically all patients admitted to the hospital, other than in pediatrics and obstetrics. Reference Borg, Suda, Scicluna and Brincat17 This intervention was also not without some controversy since consensus at the time advocated primarily risk-based MRSA screening strategies. Reference Robotham, Deeny, Fuller, Hopkins, Cookson and Stone18 Nevertheless, as we have already described previously, Reference Borg, Suda, Scicluna and Brincat17 it was felt that the hyper-prevalence of MRSA colonization in admitted patients at the time (exceeding 13%) as well as local issues which made consistent risk assessment at ward level improbable, were sufficient reasons to trial a universal strategy. This decision was vindicated by a significant reduction in all MRSA infections (including HA-MRSA-B) at very reasonable annual cost of €1058 per QALY gain per year. Reference Borg, Suda, Scicluna and Brincat17 Once again a centralized process was adopted, managed completely by care assistants employed within the MDH IPC team. They identify new daily admissions from the hospital’s patient administration system, visit the wards to perform the screening themselves directly onto culture media, and then coordinate the decolonization of all positive cases by a 5-day regimen of nasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine bathing. Reference Septimus, Weinstein, Perl, Goldmann and Yokoe19

In order to assess the impact of the interventions on HA-MRSA-B rates, we used multiple change-point analysis using the R package changepoint (R Studio Ver 2023.03.0, United States) to detect significant shifts in the mean of the data, without prior setting of any intervention points in the time series model. Reference Killick and Eckley20 Due to the retrospective nature of the data, the offline type was utilized. We adopted the binary segmentation technique proposed by Scott and Knott and avoided overestimation of the number of change points by applying penalties utilizing the Schwarz information criterion (SIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Hannan–Quinn information criterion (HQIC). Reference Scott and Knott21 A one-tailed Mann–Whitney test was used to determine whether overall incidence in the segments following each change point was significantly different from that in the segment preceding it. To justify the use of the Mann–Whitney test, we ensured that the data within segments were stationary and independent using the Dickey–Fuller test and Ljung–Box test, respectively. A Shapiro–Wilk test was also conducted to check for normality within each segment. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was chosen because the normality assumption was violated on more than one occasion. R Studio was also used to conduct this analysis.

Results

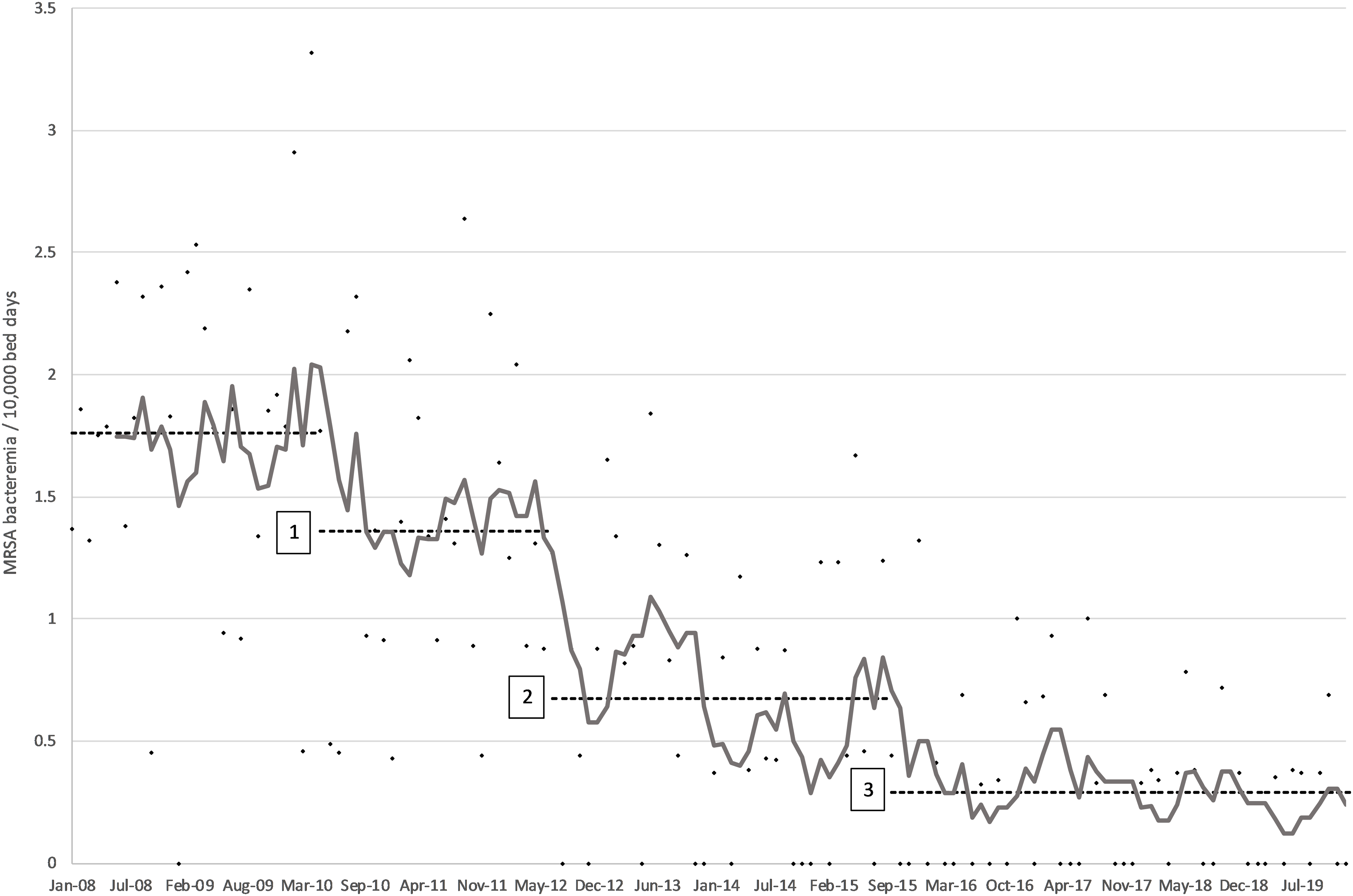

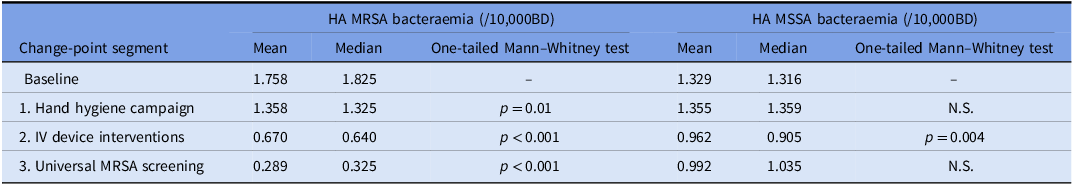

All four penalty variations yielded identical change points. The first change point was determined to have taken place in May 2010, with a mean improvement of 0.4 cases/10000BD from baseline (Fig. 2). This first change point coincided with reaching a monthly AHR consumption level in excess of 40 L/1000BD (Fig. 1). The second change point was reported at July 2012. It resulted in the highest average reduction of 0.688 cases/10000BD. The third change point was established in September 2015 and resulted in a further drop in incidence of 0.381 cases/10000BD. The mean yearly MRSA bacteremia rate had been greater than 1.7/10000BD before the start of the intervention (Fig. 2). In subsequent years, the rate reduced consistently—year on year—to reach 0.18/10000BD by 2019; a decrease of almost 90%. The only exception was 2015 when a spike in incidence was apparent in the first half of the year. At this time, mupirocin was not available due to supply issues and decolonization was attempted using polymyxin nasal ointment instead. The latter has been shown to be inferior to mupirocin to achieve MRSA decolonization. Reference O’Grady, Hirji and Pejcic-Karapetrovic22 The Mann–Whitney test showed that, in all cases, each successive segment resulted in an overall significant decrease in incidence rate, confirming that the implied cause of the change point affected an improvement (Table 2).

Figure 1. Monthly alcohol hand rub (AHR) consumption in L/1000BD (dots) with 12-month moving average (line).

Figure 2. Monthly incidence of MRSA bacteremia/10000BD (dots) with 6-month moving average (gray line) and average mean incidence for baseline and each of the three change points identified (dashed line).

Table 2. Mean and median incidence (cases/10,000BD) of healthcare-associated MRSA and MSSA bacteremia for each of the segments determined by change-point analysis

During 2011, 34 HA-MRSA-B cases were identified in MDH. Of these, 26 (83%) were related to intravascular devices. Following the start of corrective measures, IV-related HA-MRSA-B started to reduce: 13 in 2012 and 6 in 2013. In 2014, no such cases were identified by the RCAs. On the other hand, HA-MRSA-B related to other sources (primarily urinary, surgical site, and lung) remained relatively unchanged in number (Fig. 3). It was only when universal admission screening was introduced that the latter started to reduce as well. During the whole study period, no changes in the incidence of community-acquired MRSA bacteremia were identified. However, rates of healthcare-associated methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (HA-MSSA-B) showed a significant reduction in conjunction with the IV device interventions (Table 2). The segments relating to HH and MRSA screening initiatives did not show any differences in HA-MSSA-B.

Figure 3. Number of MRSA bacteraemia cases (by year) after IV device interventions attributed to IV device-related factors and to other likely causes, following root cause analysis.

Discussion

The 90% overall reduction in HA-MRSA-B at MDH is arguably one of the most effective IPC interventions reported from the Mediterranean, the European region with the highest MRSA prevalence. Reference Borg and Camilleri23 The quasi-experimental methodology and sequential implementation allowed each intervention to be evaluated independently for effect. This is often not possible in IPC multimodal initiatives, which have often been criticized for confounding effects. Reference McLaws24 Our results suggest that HH improvement, on its own, did contribute significantly toward an initial reduction in HA-MRSA-B rates. It is however to be noted that the change point happened only when AHR consumption reached 40L/1000BD, two years after the beginning of the campaign. The most recent point prevalence survey (PPS) of healthcare-associated infections (HAI) in European acute care hospitals reported that only 6 out of the 34 participating EU/EEA countries achieved this level of AHR consumption. 25 The RCA initiative, and the corrective actions implemented as a result, had the most significant influence on HA-MRSA-B rates. RCAs have already been shown to be very effective to reduce HA-BSIs. Reference Hallam, Jackson, Rajgopal and Russell26–Reference Sood, Caffrey and Krout28 However, they are often implemented as part of a bundle of measures and the specific contribution of the RCA component may be difficult to extrapolate. Our results suggest that, even on its own, RCA was a valuable tool for IPC professionals to identify possible corrective actions against HA-MRSA-B and contribute to system-wide learning within the organization. Reference Taitz, Genn and Brooks29 Interestingly, the IV device interventions addressing HA-MRSA-B also had a horizontal effect on HA-MSSA-B. This is not surprising since both are essentially the same organism with identical modes of transmission. On the other hand, neither the HH campaign nor MRSA admission screening impacted on HA-MSSA-B rates. Again, this is to be expected since neither are likely to impact significantly on MSSA colonization and subsequently infection. Reference Nurjadi, Eichel and Tabatabai30

In retrospect, we believe that the initiative was successful because it employed most of the key requirements of a proper behavior change strategy, as highlighted by Kotter’s 8-step model. Reference Campbell31 EU surveillance reports were utilized to instill urgency. The IPC team provided the vision, guidance, and communication to enable action. Short-term wins were celebrated while barriers addressed and overcome. Above all, transformational change was achieved by recognizing and understanding organizational and national cultural backgrounds and adapting interventions accordingly. Reference Borg32,Reference De Bono, Heling and Borg33 This was manifest in the predominantly top-down approach, coupled with regular communication and feedback with front-line staff. It was in line with the high uncertainty avoidance and power distance that characterizes Maltese national culture. Reference Borg32 However, this heavily centralized approach and extensive day-to-day direct involvement in all aspects of the interventions placed a heavy workload on the IPC team. Procedures that were part of previously published successful studies (such as nurse supervision of CVC insertion) were modified because they were deemed to be culturally incompatible and could have undermined the whole project. Similarly, whereas evidence-based literature was used to inform the interventions, the setting where these studies were undertaken was always considered. This was seen in the decision to set a 72-hour cutoff for duration of PVCs, although this has now been replicated in more recent studies showing a lower risk for BSI following routine replacement of PVCs than based on clinical indication. Reference Buetti, Abbas and Pittet34 We posited that the organizational context and environment of any successful study needed to be comparable to our own before the intervention was introduced. Reference Dixon-Woods, Leslie, Tarrant and Bion35 Above all, a considerable lag period (in excess of 18 months) was needed before the impact of each intervention became apparent in terms of infection outcome. This is not surprising because IPC interventions are essentially aimed at achieving behavior change. Even when eventually successful, this change needs time to materialize. Yet many IPC studies, including randomized control trials, are often organized for relatively short durations, even as little as 12 months. Reference Teesing, Richardus and Nieboer36 It should be no surprise if sufficient behavior change, that impacts on infection outcomes, cannot be achieved within such a short time interval.

In conclusion, our experience confirms that a significant reduction of multidrug-resistant HAIs is achievable, even in very high endemic settings. This can be accomplished through behavior change strategies that incorporate smart, relatively cost-neutral, interventions—such as RCAs—which provide information required for action. It is critical that interventions formulated from such data take into account, and are compatible with, local realities and culture. Lastly, because they address human behavior, a lag period is to be expected before improvement becomes evident and the implementation period needs to be long enough to take this into account.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, MAB.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize and acknowledge the contributions of all the members of the Infection Prevention and Control Department of Mater Dei Hospital in the interventions described in this publication.

Author contribution

MAB: Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Supervision; Writing—original draft;

DS: Analysis and Reviewing and editing;

ET: Administration and Reviewing & editing;

CF: Administration and Reviewing & editing;

DX: Administration and Reviewing & editing;

MBI: Analysis and Reviewing & editing.

Financial support

No competing financial interests exist.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.