In the first six months of 2012, the largest state in India's federation, Uttar Pradesh (UP or “northern province”), will go to the polls at the end of the five-year term of office of its elected government. UP is so populous that if it were sovereign, it would be the sixth largest country in the world.Footnote 1 For the five years between 2007 and 2012, a single party, the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), founded on the support of Dalits or “untouchables,”Footnote 2 formed the state's government. The 2007 election victory of the BSP was a landmark in India's social and political history as the first occasion on which the potential of the cheap, mass-based mobile phone was exploited by the leaders and dedicated followers of a long-standing political organization.

The mobile or cell phone has radically changed the potential for political organization in India, perhaps more notably there than anywhere else in the world. This is because of India's unique structures of privilege and social discrimination and the way in which cheap cell phones can subvert such structures. Mass dissemination of mobile phones has created possibilities that previously did not exist.

This essay explores these rapid and profound changes. It argues that the 2007 state elections in Uttar Pradesh were India's first “mass mobile phone” elections. To be sure, cell phones were part of Indian elections from 1996. But at that time, the cell phone was still a scarce commodity, monopolized by ruling elites and giving them another lever to control the machine of power that they drove.

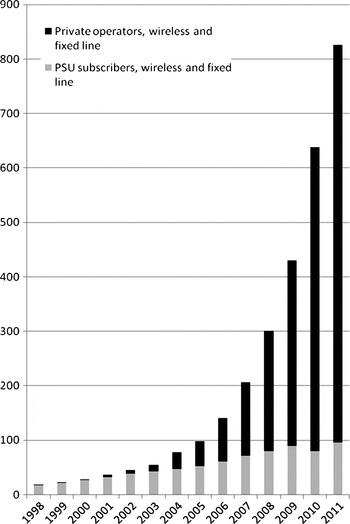

By 2007, however, the cell phone had become cheap enough for “the masses” to own. In the mid-1990s, India had fewer than 20 million phones of all kinds. By the time of the 2004 national elections, when Prime Minister Vajpayee recorded mobile-phone messages that went out to thousands of voters, India had about 75 million phones. But by 2007, when the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) won the Uttar Pradesh state elections, the country had 200 million phones; the number had almost trebled in three years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fixed-line and wireless phone connections in millions, private operators and public-sector undertakings (PSU), 1998–2011

The UP elections of 2007 brought outright victory (204 seats in 403-seat assembly) to the BSP, a partly led by an “ex”-untouchable woman, Mayawati, and founded on the support of “untouchables” or Dalits. It was the first time since 1991 that a single party had won a majority in its own right in UP. The result was a surprise: “no one foresaw such a huge victory for Mayawati,” wrote a journalist who had followed the campaign (Suman Reference Suman2007). “In the end,” wrote another, “Mayawati was right [in having predicted outright victory] and everyone else was wrong” (Hasan and Naidu Reference Hasan and Naidu2007).

The social coalition that brought victory was based on an unlikely partnership between Brahmins, the highest of castes, and Dalits, the very lowest. Together, these two groups accounted for more than 30 percent of the population of UP. If most of them could be persuaded to vote for the same candidate, such a candidate would have a strong chance of victory in a first-past-the-post, multi-candidate election. But how was such instruction to be imparted convincingly, widely and relentlessly?

Mobile phones alone did not produce this election result. But they played an essential role. The BSP campaign in 2007 changed the nature of Indian political campaigning by marrying a remarkable grassroots organization with the capacity of the mobile phone to connect, motivate and organize – and to do these things even for oppressed groups that in previous times might have had difficulty in moving freely out of their villages. Ideology and technology proved a potent combination. The organizational capacity of the BSP had been created over 20 years of bicycle-powered network-building. Placed in the hands of thousands of diligent workers, the mobile phone proved a crucial multiplier. Marginalized people acquired a new and effective tool for struggling and organizing.

While recent events across the globe have shown mobile phones to be effective tools in mass politics and democratic mobilization (Rafael Reference Rafael2003; Ayerdi Reference Ayerdi2004; Canadian Broadcasting Corporation 2004; Zhou Reference Zhou2008; Hauben Reference Hauben2008; Walton and Donner Reference Walton and Donner2009), the examples from Uttar Pradesh are different. The story in UP is not about “flash mobs” and large crowds demonstrating in the streets (Henry and Hirsch Reference Henry and Hirsch2005); rather it is about the way in which dedicated workers, hampered in the past by poor communications and constraints on their own movements, embraced the mobile phone. The wide availability of affordable mobile phones provided a political movement steeped in aspiration and shared grievance with an organizational tool unlike anything previously available. There are echoes of the Obama primary and national election campaigns in the USA in 2007 and 2008 – a similar emphasis on the combination of workers and technology “to help deliver our message person-to-person” because “trust in … traditional media sources seemed to be dwindling rapidly.” The “marrying [of] digital technology and strategy with a strong grassroots campaign” was common to Uttar Pradesh in 2007 and the US in 2007–08 (Plouffe Reference Plouffe2009 21, 36).

To be born a poor peasant in Uttar Pradesh in 1947 when India achieved independence was to be born to a hard life. To be born a poor untouchable peasant was to be born to a life that was both hard and degrading. Dalits make up about 21 percent of the population of UP – 40 million people in 2011. Although democratic India outlawed untouchability, the practice continues, in spite of reserved seats for Dalits in legislatures and positive discrimination in government jobs and education.

In electoral politics after 1947, Dalits were often treated as additional voters for the landowners on whose land they lived and worked. Stories of landlords marching “their” Dalits to the polling booths to vote as instructed were common in parts of UP throughout the first thirty years of independence (Joshi Reference Joshi1981, 1359; Pai Reference Pai2002, 37, 78). Dalits in many villages were treated like children or animals. Ancient scripture could be called on to validate their exclusion from information: “If a Sudra [and Dalits were even lower in status] … listens in on a vedic recitation, his ears shall be filled with molten tin or lac; if he repeats it, his tongue shall be cut off; if he commits it to memory, his body shall be split asunder” (Gautama Dharmasutra Reference Olivelle1999). Dalit movements were restricted, they were forced to ask permission to leave the village or hold marriages and festivals, and they faced beatings or worse if they transgressed. In 1971, Dalit literacy in UP was ten percent. In 2001, it had reached 46 percent (Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India 2001; Chanda 2004, 173). Of UP's 35 million Dalits in 2001,Footnote 3 85 percent lived in villages; more than a third of those villages had no electricity (Rangarajan Reference Rangarajan2007).

Out of a population predominantly poor, heavily discriminated against, overwhelmingly rural, and more than half illiterate, how did a political movement arise that could win elections and install a woman of its own kind as Chief Minister? Though India's attempts at positive discrimination in favor of Dalits have produced slow and spotty results, some of the spots have been bright. By the 1980s, fifteen percent of lower-order government jobs in India were held by Dalits – in line with their proportion of the population – and Dalits held six percent of higher-status government jobs. It was estimated that more than two million Dalits worked for the government (Joshi Reference Joshi1987, 86; Kapur et al. Reference Kapur, Prasad, Pritchett and Babu2010). In doing so, they acquired connections and capacities that could be turned to social and political organization.

Kanshi Ram (1934–2006), the founder of the BSP and architect of Dalit political mobilization in north India, was incapacitated by a stroke in 2003, just as mobile phones were beginning to spread across India. A relentless organizer and visionary, Kanshi Ram saw government-employed Dalits as the kernel of a Dalit middle class and the spear-point of a movement to capture political power. After fifteen years in government service, he became a fulltime organizer in 1971, dedicated to gaining political power for Dalits (Bose Reference Bose2008, 30–1). He harped on the theme that organization leading to political power must be the goal of poor and low-status Indians. He and others founded BAMCEF (All India Backward and Minority Communities Employees' Federation) in 1973 to organize the talents and resources of government servants from low-status backgrounds, particularly Dalits (Bose Reference Bose2008, 28–40). In the 1980s, Kanshi Ram carried the message of “organize to win political power” around north India by every cheap, available means. In 1983, a 40-day “cycle yatra”–a propaganda march by bicycle drawing inspiration from Mahatma Gandhi's 1930 Salt March–led by Kanshi Ram took the message of caste-based inequity across 3,000 kilometres and seven north Indian states. When ridiculed for using such antiquated methods, he foreshadowed the use to which his successors were able to put the cheap mobile phone:

Trucks, tractors, buses, car and rail are all in the hands of capitalists and those who are holding power … The very same facilities cannot be available to the oppressed and exploited people … (The) bicycle is the best weapon for them … If their two feet are all right they can reach any place to make their presence felt (quoted in Bose Reference Bose2008, 59).

By the time of his death in 2006 a mobile phone was cheaper than a bicycle, and “oppressed and exploited people” found a new weapon that could reach farther, faster and constantly.

From the BAMCEF and other experience of mobilization, a political party emerged – the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), which began contesting elections in 1984. At first, it was regularly defeated, but in 1989, it contested 372 seats in the Uttar Pradesh legislature, won 13 and took nearly 10 percent of the vote. The BSP's 67 seats in 1993 gave it a pivotal role in coalition governments and enabled Mayawati, a tough young Dalit woman mentored by Kanshi Ram, to become Chief Minister in 1995 for the first time. She again held the post briefly in 1997 and 2002–03 before the landmark election victory of the BSP in 2007.

Kanshi Ram used all means of communication that were within the reach of poor people. This included exploiting a resource that resulted from reservation of government jobs for Dalits: the significant Dalit presence in the Indian Posts and Telegraphs (IP&T). This meant, even in the 1980s, that on his mobilizing travels and cycle yatras, he could count on telegrams being sent and delivered, telephone calls made and messages transmitted, even though phones were rare and inaccessible until 1985. India's network of post offices extended deep into small towns and large villages, and Dalit employees of the IP&T were everywhere. They could usually be relied on to communicate messages about coming speakers and exhibitions, if not actually to organize such events themselves. This was in line with Kanshi Ram's goal of using this incipient middle class of “educated employees who feel deeply agitated about the miserable existence of their brethren.” (BAMCEF 1974, quoted in Bose Reference Bose2008, 34). Mayawati's father had been an employee of IP&T.

During the movement against the British, and for the first generation after independence, one of the strengths of the Indian National Congress had been its organization. It was capable of aggregating large numbers of people around common interests and ideas and of producing “party workers” who connected leaders and followers. This so-called “Congress system” was captured in an anecdote recounted by the late W. H. Morris-Jones. Researching the Congress Party in Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh in 1967, he reached the Congress office to be told by the elderly party-worker at a typewriter to come back after office hours: “Look, you must understand, I am working for the Party,” he told Morris-Jones, “and nobody can interfere with this work.” Morris-Jones concluded: “Gandhi had indeed done the trick – harnessed the traditional call of seva (service) to the modern party machine” (Morris Jones Reference Morris-Jones1987, 79–80). Kanshi Ram, BAMCEF and the BSP attracted similar commitment by the 1990s. At that time, it was based not on cell phones but on bicycles, postcards, telegrams and the rare and jealously guarded landline telephones of IP&T. We have no evidence that Kanshi Ram ever used a mobile phone; but for the BSP, the cell phone gave a dedicated team a game-changing device.

When Kanshi Ram suffered his stroke in 2003, the rapid diffusion of cheap cell phones had barely begun. India had about 50 million phones of all kinds, mostly landlines in businesses, government offices and middle class homes. Eighty percent were provided by the government's two telecommunication companies, Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd (BSNL), which served the entire country, and Maha Nagar Telecommunications Ltd (MTNL), which served the metropolises of New Delhi and Mumbai. BAMCEF and the BSP could, however, call on their adherents in Indian Post and Telegraphs. A BSP functionary recalled:

We are Dalits from a village some 60 km outside Lucknow, and it was my older brother who introduced me to the party. He was a clerk in the post office, and is now retired, but in those days they used to convey the message through the telephone and tell people when Kanshi Ram was due to arrive in the train-station. This way my brother and others like him were able to organize people from the area to come and meet Kanshi Ram in the railway meeting rooms….But now the mobile has made it very easy for us to convey our message also at village level. People can recharge for only 10 rupees.

In the same interview in June 2010, another senior functionary, Anil Kumar (pseudonym), had two mobile phones constantly ringing, one of which had a screensaver of the Chief Minister, Mayawati. When asked whether the party paid for mobile calls, he replied: “Nothing is paid by the party; people have and use their own mobiles.” Another person sitting beside him dressed in the khaki uniform of a government servant added that this was precisely why BAMCEF members were required to be educated and have a government job: so that they did not need to rely on the party. “BAMCEF members are strongly committed to the Dalit cause,” he said, “and their work is carried [on] after working hours, on Sundays and public holidays”. He then switched from English to Hindi to reflect on the past:

We went from mohalla to mohalla, door to door talking to people, even on Sunday and all other holidays…that was a time when people were possessed [hum divane te] by the ideology; we used to divide areas and go from village to village to organize the cadre and organize night meetings and only then public meetings. Now it is much easier to spread the word. (Interview June 7, 2010a)

Such commitment and organizational focus are noted by many observers; but in a time when lack of genuine ideology and commitment has been a constant refrain in discussion of political parties in India, their significance has not been adequately appreciated (Pai 2003; Kumar 2008; Choudhury Reference Choudhury2010, 111–14). This is not to argue that the BSP represented a heroic mobilization of the downtrodden masses or that the BSP government formed in 2007 transformed the lives of the poor and oppressed. It is to argue, however, that in 2007 the BSP had a large body of dedicated workers whose zeal and effectiveness were multiplied many times by their use of the mobile phone.

In transforming the mobile phone into an item of mass consumption, the price barrier was crucial. It began to be broken from 2003–04. In those years, the average cost of a call from a mobile phone fell below one rupee for 30 seconds; mobile phones increased in number from 13 million to 33 million in 12 months (TRAI 2005–06, 100). The cost of a call came within the reach of even the poorest people. The cost fell steadily thereafter, and by June 2010 one rupee could buy more than three minutes of phone time. (A rupee is worth about two cents in US currency). By 2005, the cost of a new cell phone was less than Rs 2,000 – six weeks' wages for the poorest agricultural labourer, but not an impossible dream for even poor families if a household had three or four earners.Footnote 4

The number of cell phones in Uttar Pradesh more than doubled between 2005 and 2007. When the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) analyzed phone numbers in March 2005, it recorded a total of 13.25 million phones in Uttar Pradesh. In March 2007, just prior to the state elections in May, UP recorded 30.77 million phones (TRAI 2005–06, 40; TRAI 2006–07, 41). In a population of about 180 million, this meant – in theory – one in every six people had a phone. Distribution of course was highly skewed towards middle-class people in towns and cities. In rural areas, where most of UP's population lived, mobile-phone coverage was patchy, and phone penetration was estimated to have reached 10 phones per 100 people only in 2009 (Department of Telecommunications 2009, 129). For organizational purposes, however, what was important was not that everyone owned a phone but that key organizers did. For getting people to meetings and for political evangelizing, face-to-face was best – as the Obama campaign also believed (Plouffe 2010, 378) – though a personal telephone call for a specific purpose was a strong second. More important, the mobile phone enabled meetings and talks to be organized quickly and effectively. And the phone allowed lower-level organizers to be in regular touch with people higher up in the BSP's chain of command; they experienced the exhilaration of being called by a superior and asked to provide information or carry out an assignment. The phone connected and energized as a postcard or telegram never could.

Kanshi Ram died in October 2006, less than a year before the party he founded came to power in its own right in the biggest state in India. In 2005, however, the BSP seemed stalled – capable of winning only about 20 percent of the vote in Uttar Pradesh, which roughly reflected the Dalit population of the state. Mayawati's biographer tells us that from 2005, “she sat down with her aides … to plan” for the coming elections. She increasingly welcomed the advice of Satish Mishra (b. 1952), a Brahmin lawyer who had been advocate-general of UP and then her legal adviser (Bose Reference Bose2008, 175). The arithmetic was enticing. Dalits constituted about 20 percent of UP's population; Brahmins were more than 10 percent. If large numbers of Dalits and Brahmins, coming from different ends of the old social hierarchy, could be induced to vote for the same candidate, it could produce a winning foundation.

At first glance, a Dalit-Brahmin association seemed implausible. In its early years, the BSP had constantly berated high castes. Tilak, taraju aur talwar, unko maaro juutee char was a particularly catchy slogan: “Brahmins, Banias and Rajputs – beat them with shoes.” But Brahmins in UP had been sidelined in the political equations of recent years, “orphaned by the changing contours of the two parties [Congress and Bharatiya Janata Party] that had claimed to represent their interests” (Bose Reference Bose2008, 176). From 2005, the BSP, with Satish Mishra as a diligent link to Brahmin groups, campaigned to convince Brahmins and Dalits that Brahmin-Dalit association made sense and that to vote for the BSP would serve the interests of both. The method of propagating the message, as described by Mishra and journalists who followed the story, involved dozens of meetings around the state to set up bhaichara samitis – brotherhood committees reaching down even to the level of individual polling booths. Such committees, made up of Brahmins and Dalits, disseminated the message that Brahmin-Dalit unity was desirable because it could bring electoral victory and a government sympathetic to the needs of both groups.

A polling station is based on about 1,000 voters, and with 130 million voters, there were more than 100,000 polling stations in UP in 2007. The BSP organization, and the bhaichara samitis that grew from it, did not create organizations at every one of the 100,000 polling stations; but they established thousands of polling-station-level committees in all 403 constituencies. The dedicated BSP organization came into play. Members of the party describe a six-tier system. At the top of a leadership pyramid, Mayawati and her inner group developed strategy, which was transmitted downwards from state party leaders to divisions, districts, constituencies, sectors and ultimately polling booths. At each level, there were workers willing to devote time and energy – and their mobile phones – to working for the party. Kanshi Ram had created the framework and recruited faithful workers over years of cycle yatras and touring. “To this day it is the cycle yatris and the DS-4 cadres who play a role akin to that of Mao's cadres of the Long March,” an observer asserted in 2007 (Sharma Reference Sharma2007, 17–19). In 2005–07, this network supported Satish Mishra and his associates in the mission of bonding Dalits and Brahmins. Mishra and his collaborators held scores of meetings, at which local people were inducted into bhaichara samitis and instructed in how to organize similar meetings themselves. They were also given responsibility for regular liaison with the BSP hierarchy. Mobile phone numbers were exchanged, lists of workers and their phone numbers were assembled and thereafter messages were regularly passed up and down the chain by voice and by SMS (text messaging). Workers received inspirational messages, talking points, tasks, target dates, and directions about how to organize visits by party leaders.

BAMCEF members in Lucknow elaborated on the disciplined and systematic nature of the party. They pointed out that in 2010 other parties sought to emulate the BSP system. According to them, the bhaichara samitis functioned at various levels of the party's tiered system (Interview June 8, 2010). Organizational registers, proudly shown by party workers, demonstrated a meticulous operation: remarkable record-keeping, with precise information about the composition of each sector down to individual polling booths. Pages tabulated the details of the office bearers, party volunteers, and activists. At the sector level, for example, information began with a person's name, portfolio (e.g., Organizing Secretary), father's name, caste, level of education (e.g., intermediate, junior high school, etc), address – and mobile phone number.

Underneath were listed the names of the booths within each of these sectors (between nine and twelve booths per sector). Additional information recorded the precise nature of these booths and its responsible party officials, including names, full address, and mobile phone numbers. On the right side of the page a listing of the sector's caste breakdown was recorded. For example, one sector, which was dominated by a Muslim population of 4,020 people, also listed other castes or identities, including Brahmin (1300), Vaishsava (962), Kayasth (448), Yadav (478), Punjabi (164), Passi (499) and so on. The information was regularly updated on a computer.

A senior BAMCEF member, who works as a BSNL employee – the roots in Indian Post and Telegraphs remain significant – explained that this information enabled them to decide the most effective composition of the bhaichara committees prior to elections. In a sector dominated by Brahmins, they aimed to form a Brahmin bhaichara samiti. Prior to the 2007 elections the focus was more on Dalit-Brahmin alliances, but in 2010 the focus had widened to include other groups, especially Muslims. These bhaichara samitis, he said, were formed at district or sector levels, with between 500 and 2000 participants. The steering committee would always have a Dalit as its secretary and a president from the other caste group (e.g., a Brahmin in the case of a Brahmin bhaichara samiti).

These regular connections with thousands of workers would have been impossible without the mobile phone. Uttar Pradesh, to be sure, was not awash with mobiles. By March 2007, as we have seen, rural penetration was less than 10 percent of the population. But by this stage, key people could afford phones. Activists insist that phones were not given out by political parties as enticements or rewards. Rather, workers readily volunteered to use their phones for the cause. The fact that calls were now cheap, and incoming calls were free, no doubt fostered public spirit.

The number of people actively involved in BSP organization and in the evolving bhaichara samitis reached tens of thousands. Indeed, had there been only one person per polling station in UP, more than 100,000 people would have been involved. The organization probably did not exceed that number, but simply to have a BSP organization in every constituency (403) and bhaichara samitis in 80 districts involved thousands of workers and associates. In some constituencies, organization did in fact extend down to the level of the polling station.

The mobile phone allowed this network to be created, kept fresh and made to do electorally effective work. Regular instructions came downward specifying precise activities that were to be undertaken at particular times: ensure that all potentially favorable voters in your area of responsibility were on the rolls; take particular care that all eligible (and potentially favorable) women voters were enrolled; explain why the Brahmin-Dalit alliance was beneficial; remind people of the terrible state of law and order in UP under Mulayam Singh, the incumbent Chief Minister; emphasize what would be done under a BSP government. BSP slogans were witty and instructional: “Chad gundon ki chhati pe, button dabaa do haathi pe” (to get rid of the goondas [the incumbent government], push the elephant button [the BSP's symbol on the voting machine]) (Rangarajan Reference Rangarajan2008). This cell-phone traffic increased as the election campaign began. Such phone messages came in the form of texts in Devanagari and English. Occasionally, superiors in the chain made personal calls to elicit information, pass on instructions, learn about local conditions or arrange meetings and events.

Anil Kumar, a BSP official in Lucknow, showed a page in his files headed “important numbers,” which listed the mobile numbers of key figures, including the cabinet minister Naseem Siddiqui. Workers at Kumar's level maintained regular communication with such seniors, especially during the election period, when they reported on the needs and requirements at sector and booth levels. Lower-level workers felt pride at being spoken to person-to-person by a “superior” and in having the superior's phone number on their cell phone (Interview June 8, 2010). This top-down direction was constantly informed and refined by bottom-up communication.

How important really was the mobile phone in this system? The question might be put another way: could anything like this have been made to work without the cell phone? The physical limitations of Uttar Pradesh, and the constraints on the lives of most Dalits in Uttar Pradesh, are worth reiterating. Basic communications in UP were poor, even at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The “road network [was] one of the lowest in the country” relative both to population and area (INDIA-Uttar Pradesh State Roads Project 2002). Eighty-five percent of Dalits lived in villages. Wealthier, higher-caste neighbors could sometimes prevent Dalits from moving freely in their own villages and from going outside to visit others. Strangers could be prevented from visiting Dalit areas of a village or could find their visit closely scrutinized. Cheap mobile phones nibbled away at such control and isolation. In 2005–07, though mobiles were still scarce among Dalits, they were nevertheless available and affordable for a few. And it needed only a few mobiles to transmit messages over previously formidable barriers. A single call could alert and inform hundreds of people. Such calls leapt obstacles imposed by illiteracy, bad roads, long bus rides, uncertain postal services and hostile neighbors.

The mobile phone helped in another crucial task: explaining to potentially skeptical audiences why Dalit-Brahmin cooperation was a good idea. The success of the bhaichara samitis depended on such storytelling and convincing. The BSP's long-standing unpopularity with the mainstream media made the role of personalized explanation especially important. Owned by caste-Hindus and with virtually no Dalits employed in editorial duties of any kind, major newspapers and television channels were disdainful of the BSP and often hostile to Dalit-oriented policies (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey2001, 225–38). The BSP under Kanshi Ram and Mayawati had reciprocated the disdain and hostility. In 1996, BSP workers roughed up media people who were said to have insulted Kanshi Ram and Mayawati (Hardtmann Reference Hardtmann2009, 3; Bose Reference Bose2008, 110–11). “The BSP leader's constant refrain about a biased manuvadi [caste-Hindu] media,” wrote Mayawati's biographer, “was an accurate description” (Bose Reference Bose2008, 111). The diffusion of the cell phone counteracted many of these disadvantages. For their part, Dalits were not widely exposed to mainstream media: televisions were too expensive, and newspapers had less presence among a largely illiterate, village-based population. “Dalit activists,” Hardtmann writes, “formed their own arenas … and interacted with their own networks” (Hardtmann Reference Hardtmann2009, 3). The cell phone enriched such networks, sending communication far wider, enabling it to be more frequent and making it easily accessible to people who would rather speak and listen than read and write.

On the Brahmin side of the strategy for the 2007 elections, the mobile phone allowed scores of meetings to be organized and workers recruited. Once recruited, workers could be regularly reminded of the story they were to tell and the responsibilities they were expected to fulfil. It was, after all, not an obvious message: in old-fashioned terms, the lowest and the highest were to work together for mutual benefit. Dalit-Brahmin brotherhood events discussed mutual problems and the need to promote collaboration. Talking points, intended to highlight Brahminical support for Dalits, emphasized how B. R. Ambedkar, the great Dalit leader of the nationalist era, found guidance and support from Brahmins and how even his name was given to him by his Brahmin teacher Mahadev Ambedkar, who inspired him during his early schooling (Interview, 8 June 2010). When there were doubts and questions about how to pursue such topics, workers used their cell phones to communicate with senior leaders for guidance and reinforcement.

Satish Mishra, key organizer of the BSP campaign and the bhaichara samitis, emphasized that the BSP was a cadre-based party with messages and instructions coming down from the top to individual polling booths through the tiers of organization. He was at pains to discount any suggestion that the party used mobile phones to make direct, mechanized appeals to voters. Though mainstream media were against the BSP, the party's extensive organization meant that its workers went straight to individual voters face-to-face (Interview June 7, 2010).

Mishra recounted how he spent three months from June 2005, touring every district in Uttar Pradesh and covering 23,000 kilometres, to form bhaichara samitis and to convince people why they should participate in such committees. It was difficult, he said, but he and his associates explained why age-old prejudices should be put aside and how such prejudices could be overcome. Afterwards, these committees were kept in touch and directed by mobile phones. Every member of the new organization, down to the level of the booth committee, had a mobile. The organization did not provide mobiles; people had them already and were willing to use them for party work. Cell phones kept workers motivated by reminding them of their tasks and keeping them in regular touch with the BSP organization.

The ability to converse was crucial. Since the national elections of 2004, politicians had experimented with mass voice messaging; the effects on voters were hard to gauge but mixed at best. Prime Minister Vajpayee's voice messages to hundreds of thousands of voters in the national election campaign of 2004 were judged by many to have become an annoyance. People who initially were fascinated by the calls, and wanted to talk back to the Prime Minister, soon discovered that the traffic was only one way. On the other hand, Narendra Modi's use of the same technique in the Gujarat state elections of 2007 was said to have been relatively well received (Interview June 8, 2010b). However, the mobile phone's ability to provide one-to-one conversations over vast areas was more important than its broadcast or mass-mailing capacity. As the mobile phone became available to “the masses,” the masses expected to be spoken to as individuals.

Satish Mishra believed that the Brahmin-Dalit alliance led Brahmins to encourage Dalits to vote, and that Dalits who in the past might have found it difficult to vote were induced to do so (Interview June 7, 2010b). The state-level evidence for this, however, is unconvincing. The UP elections in 2007 had the lowest overall turnout of voters since 1985 (about 46 percent; see Figure 2). It was the lowest Dalit turnout (44 percent) since 1991. However, among the rest of the population (i.e., everyone except Dalits), 2007 marked the lowest turnout (46 percent) in 30 years and nine elections. How does such a fall in participation accord with arguments about the potency of the mobile phone for political organization? One response might be that when populations lose interest in elections, the party with the strongest organization – the party best able to identify its supporters and urge them to vote – will fare best. In 2007 in Uttar Pradesh, this party was the well-organized, mobile-savvy BSP.

Figure 2. Vote turnout in Uttar Pradesh, 1977–2007. Overall Turnout marks the total votes cast measured against all eligible voters; General Turnout marks the non-scheduled caste voters who voted measured against all non-scheduled class people; SC Turnout marks scheduled caste voters who voted measured against all scheduled castes eligible to vote.

The 2007 elections in Uttar Pradesh were remarkably fair and free from intimidation. This resulted in part from the powers and determination of the Election Commission of India. Polling was carried out in seven phases over a month to allow police to move from one region to another to supervise voting. Police were brought from other parts of India to try to ensure impartiality, and the Election Commission strictly enforced the guidelines for fair conduct of elections. All this could have happened without mobile phones, but the mobile permitted rapid reporting of, and response to, breaches of the guidelines. All election agents had mobile phones. It needed only one observer and one phone call to draw attention to misbehavior, even at remote polling stations. In UP in 2007, this was doubly important for the BSP. First, the incumbent ruling party, the Samajwadi Party, had a strong-arm reputation–much of it, it appears, well deserved. Previously, a party with such capacity could capture polling booths, stuff ballot boxes and indulge in other heavy-handed and effective techniques. Second, Dalits in the past were particularly vulnerable to intimidation. They could be prevented from voting or coerced into becoming tools of vote-managing thugs. In 2007, however, people with mobile phones – election agents of the various parties, election officials and ordinary citizens – were present at every polling station. The phone numbers of election authorities were widely publicized and citizens encouraged to report irregularities. Many mobiles now had a camera. Intimidators ran the risk of being photographed and identified, and the old practices of smashing the camera or seizing the film were less likely to succeed: a photo on a mobile phone could be quickly forwarded to authorities or become an offering on YouTube. None of these possibilities would have mattered, however, unless there were an energetic Election Commission with effective police forces at its command. The ability to report malpractice instantly and to respond forcefully made for a notably fair election, and fair elections protect poor, marginalized and vulnerable voters.

Why did other parties not adopt the techniques of the BSP in 2007? First, they lacked the network of dedicated workers on which the BSP was based. The BSP found in the mobile a new and superior tool. It allowed them to transmit ideas and enthusiasm to new recruits, and it allowed party seniors to urge on followers, inform them of plans and refine campaign arrangements. But in the beginning was the organization. The mobile phone did not create it; the mobile phone only enhanced it.

Second, others did in fact see what the partnership between the cell phone and the BSP could achieve. One such observer was P. L. Punia (b. 1945). An Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer and a Dalit, Punia was three times principal secretary to Mayawati when she was Chief Minister in 1995, 1997 and 2002. “Punia,” an official told a journalist in 2009, “knows about the structure and methodology of the BSP” (Indian Express 2009). Punia and Mayawati parted ways acrimoniously in 2003, and he retired from government service in 2005 and joined the Congress Party. In the 2007 state elections, he contested and ran third behind two women in the seat of Fatehpur; but in the national elections in 2009, he won the constituency of Barabanki for the Congress with a majority of 167,000 votes over his nearest rival (Election Commission of India 2009). His methods recalled those of the BSP in 2007:

Before the election … it is easy to appoint a booth-level worker, but it's very difficult to keep them mobile and keep them activated. And that is what I did through mobile phone, and also through the material I sent off and on continuously before the election. The mobile did work …

The mobile made it possible to give booth workers meaningful tasks and for them to be in touch with the candidate and to feel that they were playing an important role in the campaign. Punia's team gave them constant activities:

[We told them] what they are supposed to do for the day – that is, the revision of electoral rolls, issue of identity cards, constitution of booth committees: … that you should have representation of women, you should have representation of Scheduled Castes, you should have representation of Backward Classes, and you should have the representation of the most dominant caste … So give them [booth committees] some work or the other and not allow them to remain idle.

If the organization is to be kept ready and useful, the sense of personal, one-to-one connection, which was important in the election campaign, continued after:

Even now people will approach me [from] … any village. I ask who was the booth adhyaksh [chairman] who was in charge of the booth, what is his mobile number, whether you were associated with me in the last elections, whether you are still in touch with the booth adhyaksh. So I will know whether he is my man or not my man. And the booth adhyaksh will also get an honour – that “I am being remembered. I am being consulted on each and every matter if it pertains to my booth.”

Such close contact was only possible through the mobile phone. Nor, given the warmth the phone conversations seemed capable of engendering, was it surprising that such party workers “had their own phones. They were not given by us. [They were] very happy to use their phones” (Interview June 5, 2010).

Six reasons explain the potency of the mobile phone for Dalit politics in Uttar Pradesh in 2007. The phone was fast, cheap, widely available and did not require high levels of literacy. It overcame physical barriers, whether imposed by social superiors or by distance and cost. It bypassed mainstream media controlled by caste-Hindus, unsympathetic to Dalit causes. It enabled the difficult message of Brahmin-Dalit alliance to be explained personally, relentlessly and widely. It fostered workers' sense of importance and purpose by enabling person-to-person conversations to instruct, inform, rally and praise. And it ensured a fair, free election by providing rapid access to responsive election officials.

As a tool for marginalized people, the cell phone is not a magic wand; but it can be a box of matches. Matches enable any individual to strike sparks. Depending on the available fuel and ingenuity, you can cook a meal, burn your fingers, start a steam engine or set fire to a forest. Mobile phones, as the BSP demonstrated in 2007, have similar potential.

Acknowledgments

Sharat Pradhan, Maxine Loynd and Professor Vivek Kumar provided invaluable help in the research and writing of this essay.