Introduction

From December 2019 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection spread rapidly around the world, and in March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic (World Health Organization, 2020).

The impact of the coronavirus disease was dramatic also because appropriate tools for diagnosis and therapy were not available at the time.

Quarantine has been defined as the separation and restriction of movement of people who have potentially been exposed to a contagious disease to ascertain if they become unwell, so reducing the risk of them infecting others (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Quarantine was used mainly at the local level during historic outbreaks, e.g. during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in African villages.

For coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), quarantine and social distancing measures were effective public health tools in limiting the dissemination and outcomes of the infection (Tognotti, Reference Tognotti2013). Although the severity of these restrictions has varied between and within countries, they have had a significant impact on people's daily life, influencing their job, leisure activities, livelihood and social relationships. Each country's general population has experienced the emotional, social and economic impact of this emergency.

Previous studies have shown that widespread outbreaks of infectious diseases, such as SARS, Ebola and H1N1, are associated with psychological distress and mental health symptoms (Bao et al., Reference Bao, Sun, Meng, Shi and Lu2020; Maalouf et al., Reference Maalouf, Mdawar, Meho and Akl2021; Chaundri et al., Reference Chaudhry, Kazmi, Sharjeel, Akhtar and Shahid2021). The psychiatric implications continued far beyond the outbreak: SARS survivors reported having persistent mental health issues years afterwards (Mak et al., Reference Mak, Chu, Pan, Yiu and Chan2009).

A review published at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020) showed that quarantines could lead to deleterious psychological effects, including post-traumatic stress symptoms, confusion, anger, infection fears, frustration and boredom.

Several studies have investigated the mental consequences of COVID-19 on target populations such as children, students and healthcare professionals (Husky et al., Reference Husky, Kovess-Masfety and Swendsen2020; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Xue, Zhou, Zhu, Liu, Zhang and Song2020; Segre et al., Reference Segre, Campi, Scarpellini, Clavenna, Zanetti, Cartabia and Bonati2021; Stocchetti et al., Reference Stocchetti, Segre, Zanier, Zanetti, Campi, Scarpellini, Clavenna and Bonati2021)

While such a focus is understandable, it is also necessary to detect relevant changes in health behaviours that may be occurring at a community level in order to better understand the range of psychosocial consequences of the pandemic's containment measures.

A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted at the beginning of the pandemic (Salari et al., Reference Salari, Hosseinian-Far, Jalali, Vaisi-Raygani, Rasoulpoor, Mohammadi, Rasoulpoor and Khaledi-Paveh2020) showed that the prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression symptoms among the general population was 30% (95% confidence interval (CI) 24.3–35.4), 32% (95% CI 28–37) and 34% (95% CI 28–41), respectively.

Since lifestyle behaviours can affect mental wellbeing and health behaviours can change during the COVID-19 pandemic (Parletta et al., Reference Parletta, Aljeesh and Baune2016; Arora and Grey, Reference Arora and Grey2020), the potential benefits of mandatory mass quarantine need to be weighed against the possible costs, including psychological ones.

Although the first wave of the pandemic seems far away, two others have followed and others, albeit less intense, may occur. The use of quarantine to deal with epidemics or pandemics, however, may occur again.

Although many studies (Necho et al., Reference Necho, Tsehay, Birkie, Biset and Tadesse2021; Prati et al., Reference Prati and Mancini2021; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Pan, Cai and Pan2021) have evaluated the mental health consequences of the current pandemic on the general population, there has been no published systematic review focusing primarily on the broader psychological impact of COVID-19 quarantine on European general population samples.

The main objective of the present study was therefore to investigate the effects of the COVID-19 quarantine during the first wave (the most intense one) on mental health and lifestyle changes of the general population in European countries. Specifically, it aimed to analyse the socio-demographic and COVID-19-related variables in order to identify those individuals at elevated risk for adverse mental health outcomes. Specific focus was placed on pre-quarantine predictors of psychological impact and stressors during quarantine.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

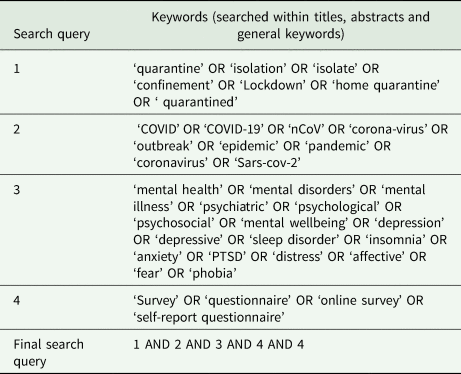

For the present review, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were followed. A computer-based literature search was conducted on the following databases: PubMed, PsycINFO and Scopus, including studies published from the inception of the pandemic (January 2020) until the 20th of April 2021. A manual search on Google Scholar was performed to identify additional relevant studies. The full list of search terms can be found in the Appendix (Table A1). In brief, we used a combination of terms relating to quarantine (e.g. ‘quarantine’, ‘isolation’, ‘confinement’ and ‘lockdown’), psychological outcomes (e.g. ‘psychological’, ‘mental health’, ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’, ‘insomnia’, ‘eating habits’ and ‘lifestyle changes’), survey (e.g. ‘online survey’ and ‘questionnaire’) and COVID-19 (e.g. ‘COVID’, ‘corona-virus’ and ‘pandemic’).

For studies to be included in this review they had to be journal articles, report on primary research, be published in peer-reviewed journals, be written in English, include participants asked to enter into quarantine outside of a hospital environment for at least 24 h and include data on the prevalence of mental health symptoms or psychological wellbeing, or on related factors. In particular, studies with a cross-sectional design and longitudinal studies with data collected only during the quarantine were included. Studies were excluded if they focused on particular subgroups of the population such as healthcare workers, students or people with chronic conditions, or if they did not have full-text availability. The present review followed the PRISMA checklist and reporting guidance (PRISMA-P Group et al., Reference Moher, Shamseer, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati, Petticrew, Shekelle and Stewart2015).

The titles and abstracts were evaluated by the authors, independently, to decide whether to include or exclude the studies. Disagreements on the eligibility of a study were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. Moreover, a review of the references of the included studies was performed. Complete references were downloaded and stored using Reference Manager 2011.0.1 software (Thompson Research Soft, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

After the first screening, only studies conducted during the first wave of the pandemic on European countries' general adult population were included. In particular, those living in countries located in the European continent, extending from the island nation of Iceland, in the west, to the Ural Mountains of Russia, in the east, were considered.

Data analysis

The network analysis approach (Borsboom and Cramer, Reference Borsboom and Cramer2013) was used to investigate the relationship between the 20 variables considered as potential risk factors for mental health outcomes related to COVID-19 quarantine (gender, age, educational level, marital status, parental status, working situation, living conditions during confinement, financial situation, social support, levels of general health, being in a vulnerable group, pre-existing mental health disorder, working situation, changes in diet and nutrition, changes in sleep, physical activity during quarantine, living in specific areas during the pandemic, symptoms of COVID-19/Physical symptoms, contact with COVID-19 cases, coping strategies/strategies to deal with stress). The Fruchterman–Reingold algorithm was used (Fruchterman and Reingold, Reference Fruchterman and Reingold1991), in which a force-directed layout dissembles the graph as a system of a large quantity of nodes or vertices. Psychological distress is seen as a network of specific risk factors (termed nodes) that dynamically interact with, and impact, one another. The nodes represent the 20 variables considered and the edges represent the connections between the nodes. Nodes act as mass particles and edges behave as springs between the nodes. The degree of a node is its number of connections (how many neighbours the variable has with other variables). The figure generated shows the most consistent associations, where thicker edges show stronger relationships and thinner edges weaker relationships.

For each node, we calculated:

• betweenness centrality, which measures all the shortest paths between every pair of nodes of the network and then counts how many times a node is on a shortest path between two others,

• closeness centrality, which calculates the shortest paths between all nodes, then assigns each node a score based on its sum of shortest paths,

• eigen centrality, which measures a node's influence based on the number of links it has to other nodes in the network and can identify nodes with an influence over the whole network, not just those directly connected to it.

A community detection analysis was carried out using the Louvain method (Blondel et al., Reference Blondel, Guillaume, Lambiotte and Lefebvre2008) to extract communities and calculate modularity. It is one of the most frequently used methods for clustering on large networks, it is very efficient and allows one to define communities in a hierarchical way to group together certain nodes, diminish the dimensionality of a dataset and facilitate interpretability. Network analysis was performed using Gephi version 0.9.2 (Bastian et al., Reference Bastian, Heymann and Jacomy2009).

Methodological quality/bias risk were recorded using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional and cohort studies (see Appendix Tables A2 and A3).

Results

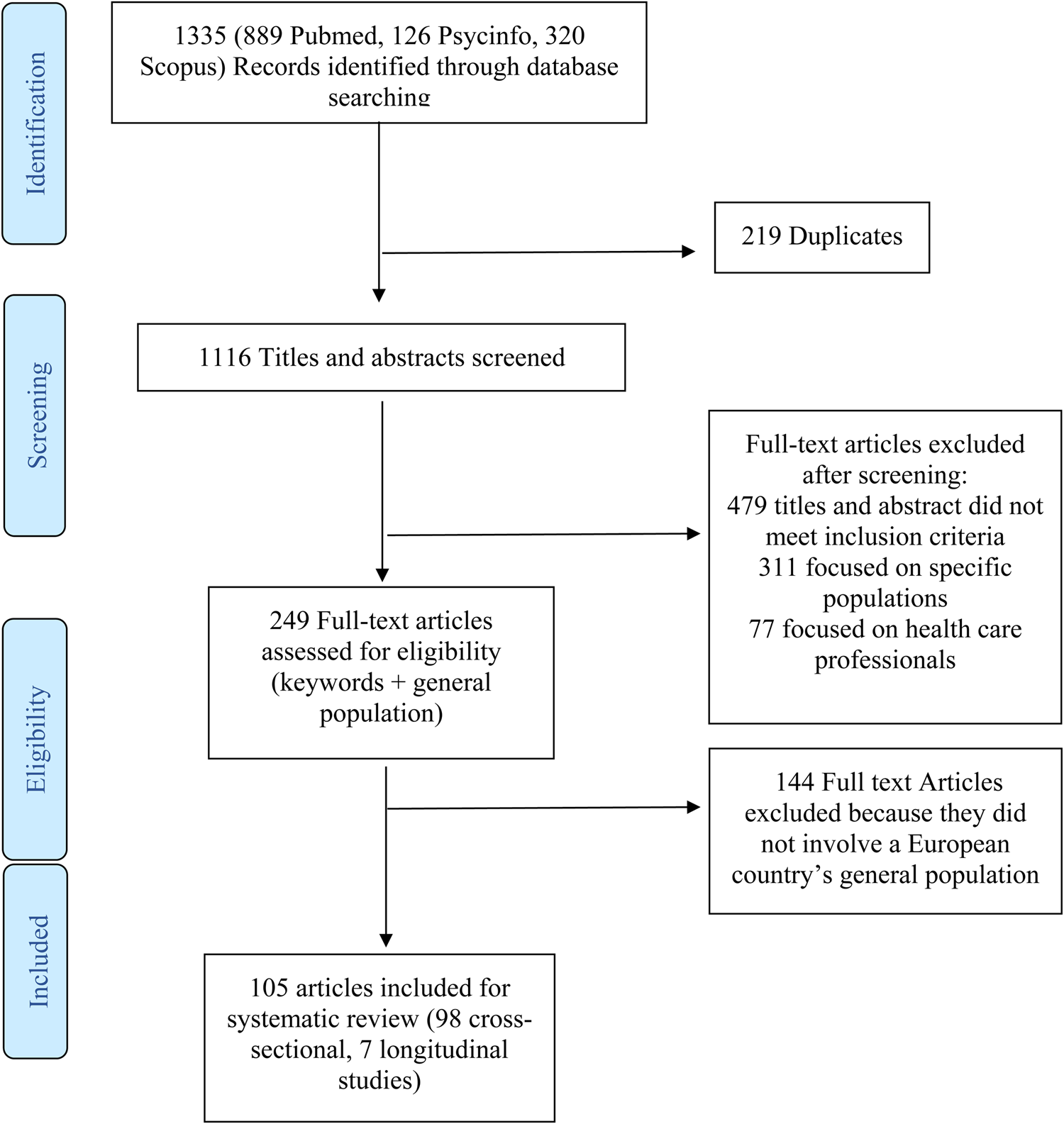

Figure 1 presents the procedural steps adopted and the record count, duplicates and final studies obtained after screening. The initial search yielded 1335 studies, of which 105 included relevant data and were included in this review.

Fig. 1. Study selection.

An overview with the characteristics of the studies is presented in online Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

All eligible studies were included in the review, regardless of their quality assessment results. Of the 98 cross-sectional studies, 45 studies (46%) were of very good quality (maximum score on the JBI) and 8 (9%) were of poor quality (JBI score <5 points). All cohort studies were of good quality. Selected studies were conducted mainly in 17 different countries (Italy: n = 39, Spain: n = 25, UK: n = 9 and Greece: n = 4).

The psychological impact of quarantine

Seventy-nine studies reported anxiety symptoms in the general population, with a prevalence ranging from 5.5 to 70.4%. The highest levels of anxiety were found in an Italian study (Di Renzo et al., Reference Di Renzo, Gualtieri, Cinelli, Bigioni, Soldati, Attinà, Bianco, Caparello, Camodeca, Carrano, Ferraro, Giannattasio, Leggeri, Rampello, Lo Presti, Tarsitano and De Lorenzo2020); these involved 70.4% of the enrolled population, 57.8% of whom with physical manifestations of anxiety (tachycardia, headache, sweating). On the contrary, three studies (Bonati et al., Reference Bonati, Campi, Zanetti, Cartabia, Scarpellini, Clavenna and Segre2021; Budimir et al., Reference Budimir, Pieh, Dale and Probst2021; Silva Moreira et al., Reference Silva Moreira, Ferreira, Couto, Machado-Sousa, Fernández, Raposo-Lima, Sousa, Picó-Pérez and Morgado2021) found low percentages of anxiety symptoms (<10% of the sample).

A comparative investigation between Spanish and Greek participants (Papandreou et al., Reference Papandreou, Arija, Aretouli, Tsilidis and Bulló2020) observed a similar prevalence of moderate and severe anxiety symptoms, with 12.3% in Spain and 13.2% in Greece. Similar rates were found also in a German study (Munk et al., Reference Munk, Schmidt, Alexander, Henkel and Hennig2020), in which 12% of the sample met the criteria for the general anxiety disorder (GAD) during the lockdown, compared with 2% before the pandemic.

Depressive symptomatology and mood variables were assessed in 74 studies and their clinical prevalence ranged from 3.2 to 82.6%. Sixteen studies classified the frequency and severity of symptoms in three categories: mild, moderate and severe. The lowest percentages of severe depressive symptoms were found in 3.2% of the Austrian sample (Budimir et al., Reference Budimir, Pieh, Dale and Probst2021) and 9.3% of the Greek sample (Fountoulakis et al., Reference Fountoulakis, Apostolidou, Atsiova, Filippidou, Florou, Gousiou, Katsara, Mantzari, Padouva-Markoulaki, Papatriantafyllou, Sacharidi, Tonia, Tsagalidou, Zymara, Prezerakos, Koupidis, Fountoulakis and Chrousos2021). Close rates were reported in the Portuguese population (Paulino et al., Reference Paulino, Dumas-Diniz, Brissos, Brites, Alho, Simões Mário and Silva Carlos2021) in which only 11.7% of the participants presented moderate to severe depressive symptoms on the ‘Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale’ (DASS). On the contrary, the findings of a Polish study (Bodecka et al., Reference Bodecka, Nowakowska, Zajenkowska, Rajchert, Kaźmierczak and Jelonkiewicz2021) showed that the majority of participants displayed at least mild depressive symptoms (82.6%). Nearly two-thirds of the Italian respondents (61.3%) experienced depressed mood (Di Renzo et al., Reference Di Renzo, Gualtieri, Cinelli, Bigioni, Soldati, Attinà, Bianco, Caparello, Camodeca, Carrano, Ferraro, Giannattasio, Leggeri, Rampello, Lo Presti, Tarsitano and De Lorenzo2020).

Psychological distress has been assessed with different tools: the majority of the included studies used the DASS stress scale. Four Italian studies (Costantini and Mazzotti, Reference Costantini and Mazzotti2020; Landi et al., Reference Landi, Pakenham, Boccolini, Grandi and Tossani2020; Pakenham et al., Reference Pakenham, Landi, Boccolini, Furlani, Grandi and Tossani2020; Bonati et al., Reference Bonati, Campi, Zanetti, Cartabia, Scarpellini, Clavenna and Segre2021) used the ‘COVID-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index (CPDI)’ with positive responses ranging from 15 to 40%. Nearly one-third of people experienced symptoms of mild to moderate and severe peritraumatic distress in two studies (Costantini and Mazzotti, Reference Costantini and Mazzotti2020; Pakenham et al., Reference Pakenham, Landi, Boccolini, Furlani, Grandi and Tossani2020), while lower rates (15.5% of the sample) were reported in another study (CPDI mean 17.95, s.d. 11.50) (Landi et al., Reference Landi, Pakenham, Boccolini, Grandi and Tossani2020).

Eighteen studies focused their attention on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. In total, 54.4% of the Italian participants met criteria for a clinical level of stress related problems and 30% of the sample had probable diagnosis of PTSD (Panno et al., Reference Panno, Carbone, Massullo, Farina and Imperatori2020). Lower scores of PTSD (5.1%) were reported in a study (Favieri et al., Reference Favieri, Forte, Tambelli and Casagrande2021) that specifically used the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Related to COVID-19 (COVID-19-PTSD). High levels of avoidance symptoms at the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) were found in two studies (Fiorillo et al., Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano, Albert, Carmassi, Carrà, Cirulli, Dell'Osso, Nanni, Pompili, Sani, Tortorella and Volpe2020; Jiménez et al., Reference Jiménez, Sánchez-Sánchez and García-Montes2020).

Seventeen studies focused specifically on resilience and/or coping strategies, i.e. the individual's ability to cope with stress and adapt to changes. Resilience has been associated with a lower risk for any mental health symptoms; the same results were obtained regarding coping (Munk et al., Reference Munk, Schmidt, Alexander, Henkel and Hennig2020). A higher score on the positive coping strategy dimension was associated with a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms, while more supportive/distractive strategies were associated with an increased prevalence (Skapinakis et al., Reference Skapinakis, Bellos, Oikonomou, Dimitriadis, Gkikas, Perdikari and Mavreas2020).

Pre-quarantine predictors of psychological impact

Several predictive factors were identified from the included studies.

Female gender is the most common risk factor associated with psychological symptoms during the COVID emergency. The risk of developing anxiety, depression, distress symptoms or PTSD was double in female compared to male participants (Casagrande et al., Reference Casagrande, Favieri, Tambelli and Forte2020; Fiorillo et al., Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano, Albert, Carmassi, Carrà, Cirulli, Dell'Osso, Nanni, Pompili, Sani, Tortorella and Volpe2020; Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Lo Moro, Voglino, Bert and Siliquini2020; Landi et al., Reference Landi, Pakenham, Boccolini, Grandi and Tossani2020; Mariani et al., Reference Mariani, Renzi, Di Trani, Trabucchi, Danskin and Tambelli2020; Mazza et al., Reference Mazza, Ricci, Biondi, Colasanti, Ferracuti, Napoli and Roma2020; Pieh et al., Reference Pieh, Budimir and Probst2020; Rodríguez-Rey et al., Reference Rodríguez-Rey, Garrido-Hernansaiz and Collado2020; Suso-Ribera and Martín-Brufau, Reference Suso-Ribera and Martín-Brufau2020; Bonati et al., Reference Bonati, Campi, Zanetti, Cartabia, Scarpellini, Clavenna and Segre2021; Rettie and Daniels, Reference Rettie and Daniels2021). On the contrary, a Spanish study reported similar levels of anxiety, stress and depression (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., Reference Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Idoiaga Mondragon, Dosil Santamaría and Picaza Gorrotxategi2020). Women reported more frequent and severe sleeping problems (such as insomnia) than men (Bacaro et al., Reference Bacaro, Chiabudini, Buonanno, De Bartolo, Riemann, Mancini and Baglioni2020; Casagrande et al., Reference Casagrande, Favieri, Tambelli and Forte2020; Margetić et al., Reference Margetić, Peraica, Stojanović and Ivanec2021); they exhibited more PTSD or secondary traumatic stress and posttraumatic growth, were less resilient and used all kinds of coping strategies more often (Kalaitzaki, Reference Kalaitzaki2021).

An age-related variation was analysed in different studies: the psychological impact of COVID-19 confinement seems to ameliorate as people get older. The youngest participants (<35 years old) showed higher levels of depression, anxiety, stress, insomnia and PTSD symptoms compared to the other age groups (Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Frontini, Amaro, Salvador, Matos, Morouço and Rebelo-Gonçalves2020; Bacaro et al., Reference Bacaro, Chiabudini, Buonanno, De Bartolo, Riemann, Mancini and Baglioni2020; Bonsaksen et al., Reference Bonsaksen, Heir, Schou-Bredal, Ekeberg, Skogstad and Grimholt2020; Rodríguez-Rey et al., Reference Rodríguez-Rey, Garrido-Hernansaiz and Collado2020; Paulino et al., Reference Paulino, Dumas-Diniz, Brissos, Brites, Alho, Simões Mário and Silva Carlos2021; Rettie and Daniels, Reference Rettie and Daniels2021; Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Jannini, Socci, Pacitti and Lorenzo2021). The greater vulnerability to distress in young adulthood could be due to the precariousness of the working activities, with consequent interruption of income, and/or the interruption of the initial phase of development of one's professional activity, and/or the presence of children, with resulting age-related concerns or the forced cohabitation in a phase in which young adults would normally leave the family of origin. Age remained positively associated with wellbeing and negatively associated with depression (Dawson and Golijani-Moghaddam, Reference Dawson and Golijani-Moghaddam2020): marked differences in prevalence of depression were found between 18 and 24 year (63.3%) olds and people over 65 years of age (11.5%) (Pieh et al., Reference Pieh, Budimir, Delgadillo, Barkham, Fontaine and Probst2021). A similar pattern, even if slighter, was reported for sleep problems (Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Lo Moro, Voglino, Bert and Siliquini2020; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Léger, Fressard, Peretti-Watel and Verger2021). Results of a Spanish (Vicario-Merino, Reference Vicario-Merino2020) and a UK study (Neill et al., Reference Neill, Blair, Best, McGlinchey and Armour2021) stated that symptoms of stress and depression tended to increase with an increase in age range.

Being more educated predicted greater wellbeing: lower educational status was significantly associated with higher depression, anxiety and PTSD symptoms (Benke et al., Reference Benke, Autenrieth, Asselmann and Pané-Farré2020; Di Crosta et al., Reference Di Crosta, Palumbo, Marchetti, Ceccato, La Malva, Maiella, Cipi, Roma, Mammarella, Verrocchio and Di Domenico2020; Haesebaert et al., Reference Haesebaert, Haesebaert, Zante and Franck2020; Skapinakis et al., Reference Skapinakis, Bellos, Oikonomou, Dimitriadis, Gkikas, Perdikari and Mavreas2020; Suso-Ribera and Martín-Brufau, Reference Suso-Ribera and Martín-Brufau2020; Gutiérrez-Hernández et al., Reference Gutiérrez-Hernández, Fanjul, Díaz-Megolla, Reyes-Hurtado, Herrera-Rodríguez, Enjuto-Castellanos and Peñate2021; Silva Moreira et al., Reference Silva Moreira, Ferreira, Couto, Machado-Sousa, Fernández, Raposo-Lima, Sousa, Picó-Pérez and Morgado2021). The trend of the association with education level, however, is likely also related also to the cultural context, as found in Italian results (Bonati et al., Reference Bonati, Campi, Zanetti, Cartabia, Scarpellini, Clavenna and Segre2021) v. Portuguese ones (Paulino et al., Reference Paulino, Dumas-Diniz, Brissos, Brites, Alho, Simões Mário and Silva Carlos2021).

Moreover, having a partner also predicted greater wellbeing (Haesebaert et al., Reference Haesebaert, Haesebaert, Zante and Franck2020): married participants and those cohabiting with their partner showed significantly lower psychological impact and felt less lonely than single participants (Balsamo and Carlucci, Reference Balsamo and Carlucci2020; Cerbara et al., Reference Cerbara, Ciancimino, Crescimbene, La Longa, Parsi, Tintori and Palomba2020; Saita et al., Reference Saita, Facchin, Pagnini and Molgora2021). Although, an Italian study (Velotti et al., Reference Velotti, Rogier, Beomonte Zobel, Castellano and Tambelli2021) reported that having a partner was associated with overeating and social network use during the quarantine, sharing everyday life with someone during quarantine was a protective factor (Dawson and Golijani-Moghaddam, Reference Dawson and Golijani-Moghaddam2020; Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Lo Moro, Voglino, Bert and Siliquini2020).

Additionally, living with children in the household was revealed as a protective factor against psychological distress, anxiety and depressive symptoms in five different studies (Gómez-Salgado et al., Reference Gómez-Salgado, Andrés-Villas, Domínguez-Salas, Díaz-Milanés and Ruiz-Frutos2020; Mazza et al., Reference Mazza, Ricci, Biondi, Colasanti, Ferracuti, Napoli and Roma2020; Rodríguez-Rey et al., Reference Rodríguez-Rey, Garrido-Hernansaiz and Collado2020; Ellen and De Vriendt Patricia, Reference Ellen and De Vriendt Patricia2021; Saita et al., Reference Saita, Facchin, Pagnini and Molgora2021). In particular, a low rate of psychological distress was observed among people living with older children or adolescents (Gómez-Salgado et al., Reference Gómez-Salgado, Andrés-Villas, Domínguez-Salas, Díaz-Milanés and Ruiz-Frutos2020; Rodríguez-Rey et al., Reference Rodríguez-Rey, Garrido-Hernansaiz and Collado2020), but those living with children under ten had poorer wellbeing (Haesebaert et al., Reference Haesebaert, Haesebaert, Zante and Franck2020).

The impact of confinement was more damaging for people living in very poor cohabitation conditions. In particular, participants living in houses of more than 120 square meters showed lower psychological impact, stress, anxiety and depression symptoms than those living in less than 30 square meters (odds ratio (OR) 1.98, 95% CI 1.19–3.30) (Ramiz et al., Reference Ramiz, Contrand, Rojas Castro, Dupuy, Lu, Sztal-Kutas and Lagarde2021). Moreover, people with access to an outdoor space (e.g. garden, balcony) had higher wellbeing scores (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.00–1.89) (Ramiz et al., Reference Ramiz, Contrand, Rojas Castro, Dupuy, Lu, Sztal-Kutas and Lagarde2021) and better mental health (Haesebaert et al., Reference Haesebaert, Haesebaert, Zante and Franck2020; Ellen and De Vriendt Patricia, Reference Ellen and De Vriendt Patricia2021). Both the number of cohabitants and the quality of the relationships must be taken into account, however, levels of psychological distress were higher and sleep quality was lower in people living alone (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Masegoso and Hernández-Espeso2021).

Being affected by a pre-existing mental disorder or having a pre-existing physical disease were found to be factors associated with worse levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms (Fiorillo et al., Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano, Albert, Carmassi, Carrà, Cirulli, Dell'Osso, Nanni, Pompili, Sani, Tortorella and Volpe2020; Mazza et al., Reference Mazza, Ricci, Biondi, Colasanti, Ferracuti, Napoli and Roma2020; Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Masegoso and Hernández-Espeso2021; Rettie and Daniels, Reference Rettie and Daniels2021). In particular, people in ‘vulnerable’ groups were significantly more anxious, and more anxious concerning their health, compared to individuals in nonvulnerable groups (Rettie and Daniels, Reference Rettie and Daniels2021).

Stressors during quarantine

Unemployed participants, who were more vulnerable to the possible economic crisis in the pandemic's aftermath, presented higher rates of depression, anxiety and stress symptoms compared to employed participants (Benke et al., Reference Benke, Autenrieth, Asselmann and Pané-Farré2020; Pieh et al., Reference Pieh, Budimir and Probst2020; Bonati et al., Reference Bonati, Campi, Zanetti, Cartabia, Scarpellini, Clavenna and Segre2021; Paulino et al., Reference Paulino, Dumas-Diniz, Brissos, Brites, Alho, Simões Mário and Silva Carlos2021). Unemployed participants were also at higher risk of developing sleep disorders (68%), often associated with some impairment of their daytime daily activities (OR 1.34; 95% 95% CI 1.02–1.70) (Casagrande et al., Reference Casagrande, Favieri, Tambelli and Forte2020; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Léger, Fressard, Peretti-Watel and Verger2021). Working outside the home was associated with higher levels of psychological distress: people working in-presence showed significantly higher psychological impact compared to those working remotely (Di Giuseppe et al., Reference Di Giuseppe, Zilcha-Mano, Prout, Perry, Orrù and Conversano2020; Gómez-Salgado et al., Reference Gómez-Salgado, Andrés-Villas, Domínguez-Salas, Díaz-Milanés and Ruiz-Frutos2020; Mazza et al., Reference Mazza, Ricci, Biondi, Colasanti, Ferracuti, Napoli and Roma2020; Paulino et al., Reference Paulino, Dumas-Diniz, Brissos, Brites, Alho, Simões Mário and Silva Carlos2021), although the type of job and professional role may affect the relationship (Fiorenzato et al., Reference Fiorenzato, Zabberoni, Costa and Cona2021). Economic stability, and socioeconomic status in general, are related to depression, anxiety and PTSD symptoms (Di Crosta et al., Reference Di Crosta, Palumbo, Marchetti, Ceccato, La Malva, Maiella, Cipi, Roma, Mammarella, Verrocchio and Di Domenico2020; Prati, Reference Prati2021): participants with high monthly family income showed lower psychological impact than those whose family income was lower (Nese et al., Reference Nese, Riboli, Brighetti, Sassi, Camela, Caselli, Sassaroli and Borlimi2022; Pieh et al., Reference Pieh, Budimir and Probst2020, Reference Pieh, Budimir, Delgadillo, Barkham, Fontaine and Probst2021; Skapinakis et al., Reference Skapinakis, Bellos, Oikonomou, Dimitriadis, Gkikas, Perdikari and Mavreas2020; Pérez-Rodrigo et al., Reference Pérez-Rodrigo, Gianzo Citores, Hervás Bárbara, Ruiz-Litago, Casis Sáenz, Arija, López-Sobaler, Martínez de Victoria, Ortega, Partearroyo, Quiles-Izquierdo, Ribas-Barba, Rodríguez-Martín, Salvador Castell, Tur, Varela-Moreiras, Serra-Majem and Aranceta-Bartrina2021).

Health became one of the primary concerns during the COVID-19 confinement. Symptomatic individuals expressed higher psychological impact and increased levels of depression, anxiety, stress symptoms and sleep disorders; these symptoms could be interpreted as potential symptoms of COVID-19 (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Léger, Fressard, Peretti-Watel and Verger2021; Paulino et al., Reference Paulino, Dumas-Diniz, Brissos, Brites, Alho, Simões Mário and Silva Carlos2021; Vujčić et al., Reference Vujčić, Safiye, Milikić, Popović, Dubljanin, Dubljanin, Dubljanin and Čabarkapa2021). Patients with polymerase chain reaction-confirmed COVID-19 reported greater sleep problems (52% severe) and worse levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms (Fiorillo et al., Reference Fiorillo, Sampogna, Giallonardo, Del Vecchio, Luciano, Albert, Carmassi, Carrà, Cirulli, Dell'Osso, Nanni, Pompili, Sani, Tortorella and Volpe2020). Having had a contact with a positive case in the previous 14 days showed a statistically significant relationship with the presence of psychological distress (Gómez-Salgado et al., Reference Gómez-Salgado, Andrés-Villas, Domínguez-Salas, Díaz-Milanés and Ruiz-Frutos2020).

Home confinement affected habits and lifestyle (in terms of sleep disorders, food consumption and physical activity), inducing common mental health problems (Balanzá-Martínez et al., Reference Balanzá-Martínez, Kapczinski, de Azevedo Cardoso, Atienza-Carbonell, Rosa, Mota and De Boni2021).

In total, 74% of the participants of a French study reported trouble sleeping, of whom females and the young had greater frequency and severity (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Léger, Fressard, Peretti-Watel and Verger2021). Reduced sleep, poor sleep quality and changes in usual sleep patterns were associated with more negative mood and anxiety symptoms (Bacaro et al., Reference Bacaro, Chiabudini, Buonanno, De Bartolo, Riemann, Mancini and Baglioni2020; Suso-Ribera and Martín-Brufau, Reference Suso-Ribera and Martín-Brufau2020). Adhering to a routine, maintaining the same weight and moderate physical exercise were associated with fewer negative effects, indicating that they are important protective factors (Gismero-González et al., Reference Gismero-González, Bermejo-Toro, Cagigal, Roldán, Martínez-Beltrán and Halty2020). Age was inversely related to dietary control, and being female was associated with being more anxious and disposed to eating comfort food than males (Di Renzo et al., Reference Di Renzo, Gualtieri, Cinelli, Bigioni, Soldati, Attinà, Bianco, Caparello, Camodeca, Carrano, Ferraro, Giannattasio, Leggeri, Rampello, Lo Presti, Tarsitano and De Lorenzo2020).

Increased emotional eating was predicted by higher depressive and anxiety symptoms, quality of personal relationships and quality of life, while an increase in bingeing was predicted by higher stress (Cecchetto et al., Reference Cecchetto, Aiello, Gentili, Ionta and Osimo2021).

The respondents who maintained the same physical activity habits had higher levels of positive emotions (energy), lower levels of negative emotions (fear and anxiety) and lower levels of experienced symptoms (headache and fatigue) (Di Corrado et al., Reference Di Corrado, Magnano, Muzii, Coco, Guarnera, De Lucia and Maldonato2020). Increased duration and greater intensity of physical activity were both associated with further reduction in the prevalence of depression (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Tully, Barnett, Lopez-Sanchez, Butler, Schuch, López-Bueno, McDermott, Firth, Grabovac, Yakkundi, Armstrong, Young and Smith2020; Pieh et al., Reference Pieh, Budimir and Probst2020), in particular in females, suggesting that variations in physical activity habits may have more influence in women's psychological status than in men's (Maugeri et al., Reference Maugeri, Castrogiovanni, Battaglia, Pippi, D'Agata, Palma, Di Rosa and Musumeci2020).

Network analysis

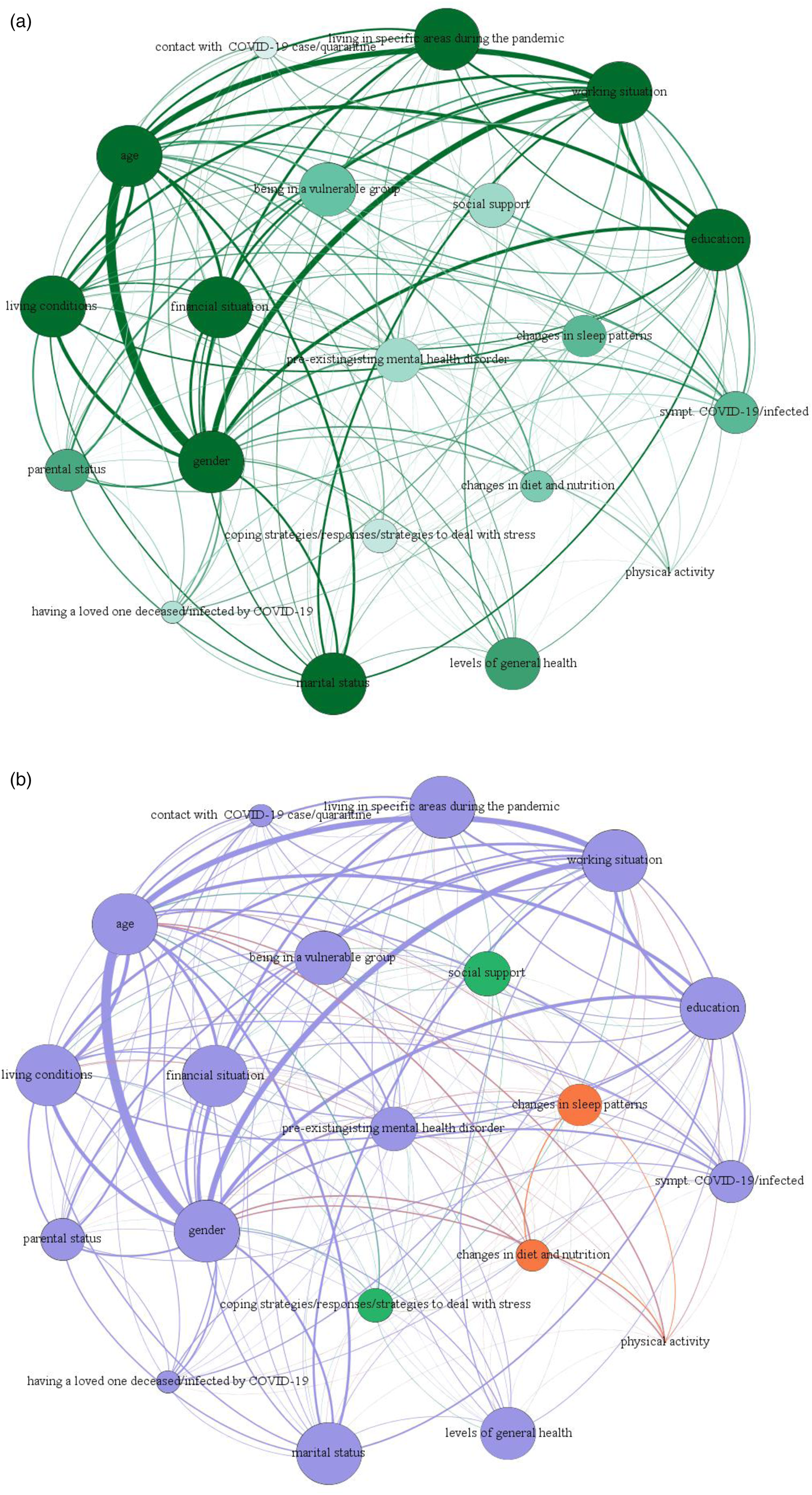

The connections between the 20 prevalent variables analysed in the retrieved studies and the structure of the network are shown in Fig. 2a, where the diameter of the node refers to the degree centrality and the hue of the node refers to betweenness centrality (darker = higher value). The network had 330 non-zero edges out of 380 possible edges. The weights of the connections are presented in online Supplementary Table 3.

Fig. 2. Network analysis.

In agreement with the narrative analysis reported above, the strongest connection emerged between gender and age, meaning that these were found to be the most common risk factors for psychological distress during quarantine. A cluster was found between age, gender, living in specific areas and working situation during the pandemic. Other noteworthy associations were reported between gender and working situation, age and living area, and working situation and living area, during the quarantine.

Figure 2b shows the results of the community detection analysis, where the colour of the node refers to the partition of the network. All nodes related to socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, working situation, living condition, financial situation and marital status) and variables related to health (symptoms of COVID-19/physical symptoms/being infected by COVID-19, pre-existing mental health disorder) formed one large module (node in violet). Two nodes were found outside this large module: the first comprised of changes in diet and nutrition, changes in sleep patterns and physical activity (node in orange); the second one (node in green) was related to coping strategies/responses/strategies to deal with stress and social support.

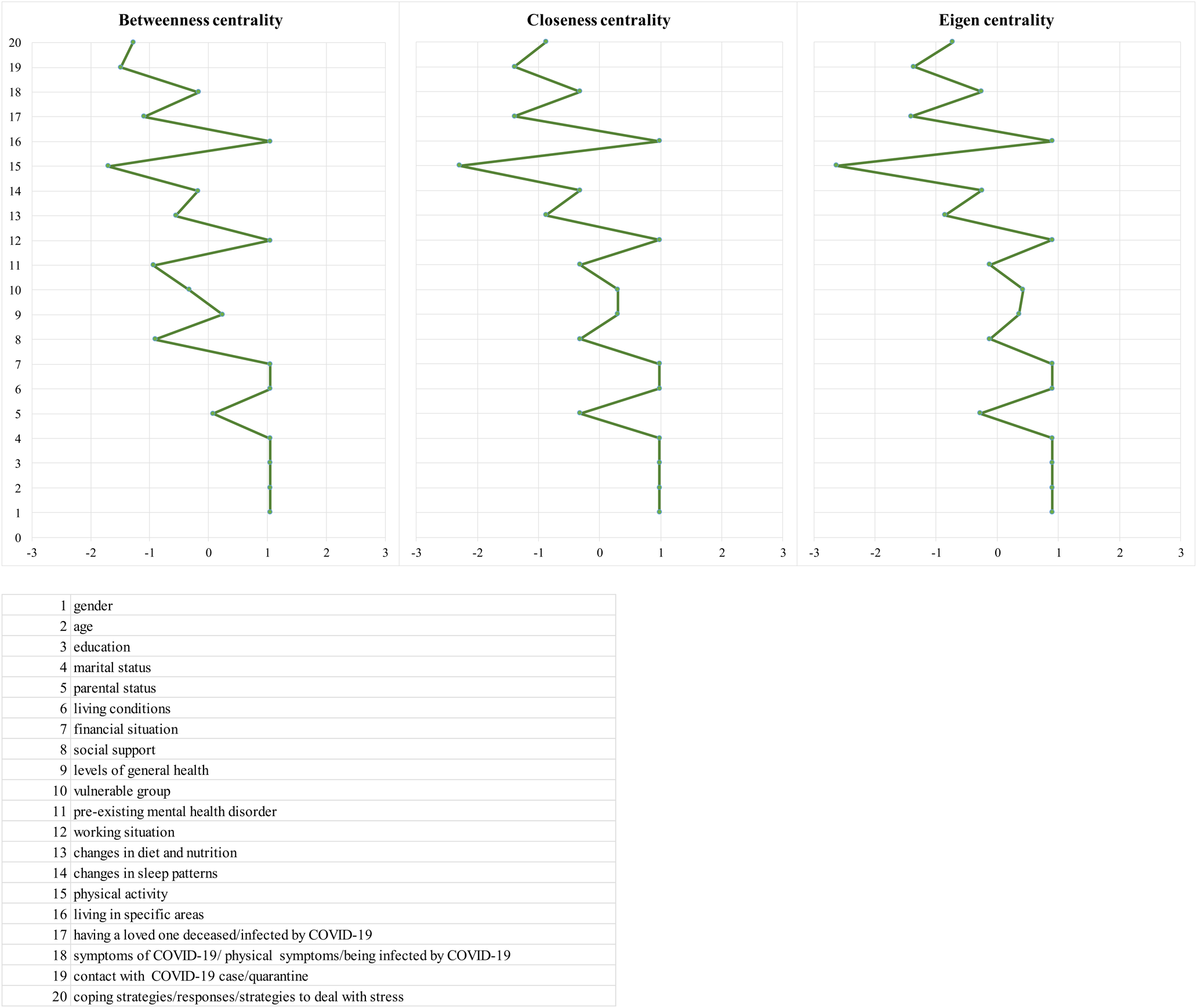

Figure 3 shows the resulting plot for centrality metrics, which highlights the differences in connectivity of the network.

Fig. 3. Centrality measures (centrality metrics are shown as standardised z-scores).

The three indices are significantly intercorrelated with each other: the correlation between eigen and closeness is 0.99 (p < 0.01), the correlation between eigen and betweenness is 0.91 (p < 0.01) and the correlation between closeness and betweenness is 0.95 (p < 0.01).

Gender, age, education, marital status, living conditions, financial situation, working situation and living in specific areas have the highest betweenness, closeness and eigen strengths, being the most central nodes, suggesting that they have the most connections in the network.

All the centrality measures indicate that the most central isolation variables in the network are physical activity, contact with COVID-19 case/quarantine and coping strategies/responses/strategies to deal with stress. Parental status, levels of general health, changes in sleep patterns and symptoms of COVID-19/physical symptoms/being infected by COVID-19 are the most central variables in the distribution of the three z-scored centrality metrics.

Discussion

This systematic review has analysed data from different studies that investigated the psychological impact of the quarantine on the general European population during the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Similar to those of other reviews (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Guo, Yu, Jiang and Wang2020; Salari et al., Reference Salari, Hosseinian-Far, Jalali, Vaisi-Raygani, Rasoulpoor, Mohammadi, Rasoulpoor and Khaledi-Paveh2020), the findings of the present study highlight the fact that anxiety, depression, distress and post-traumatic symptoms were frequently experienced during the COVID-19 quarantine and were often associated with changes in sleeping and eating habits. In particular, the overall effect of the pandemic has been linked with worsening psychiatric symptoms. The long-term effect of direct COVID-19 infection has, however, been associated with no, or mild, symptoms (Bourmistrova et al., Reference Bourmistrova, Solomon, Braude, Strawbridge and Carter2022)

These data should be interpreted with caution since different studies reported a considerable heterogeneity of mental health problems: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic may have been different across different social groups and across different contexts and countries.

An increase in mental health problems was seen from pre-pandemic assessments through the first phase of lockdown; during lockdown, no uniform trend could be identified and after lockdown, mental health problems decreased slightly (Richter et al., Reference Richter, Riedel-Heller and Zuercher2021).

Similarly, another recent review (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Sutin, Daly and Jones2022) observed an increase in mental health symptoms among most population sub-groups and symptom types soon after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which then decreased and were comparable to pre-pandemic levels by mid-2020.

On the contrary, a relatively small effect of lockdowns on mental health was reported (Prati and Mancini, Reference Prati and Mancini2021) providing evidence of people's robust capacity for resilience.

Several issues should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings of the current study.

Only studies written in English have been considered in the present review, and this may have led to some bias, although a study conducted in 2012 (Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Polisena, Husereau, Moulton, Clark, Fiander, Mierzwinski-Urban, Clifford, Hutton and Rabb2012) showed that little evidence of bias was introduced from the exclusion of non-English studies.

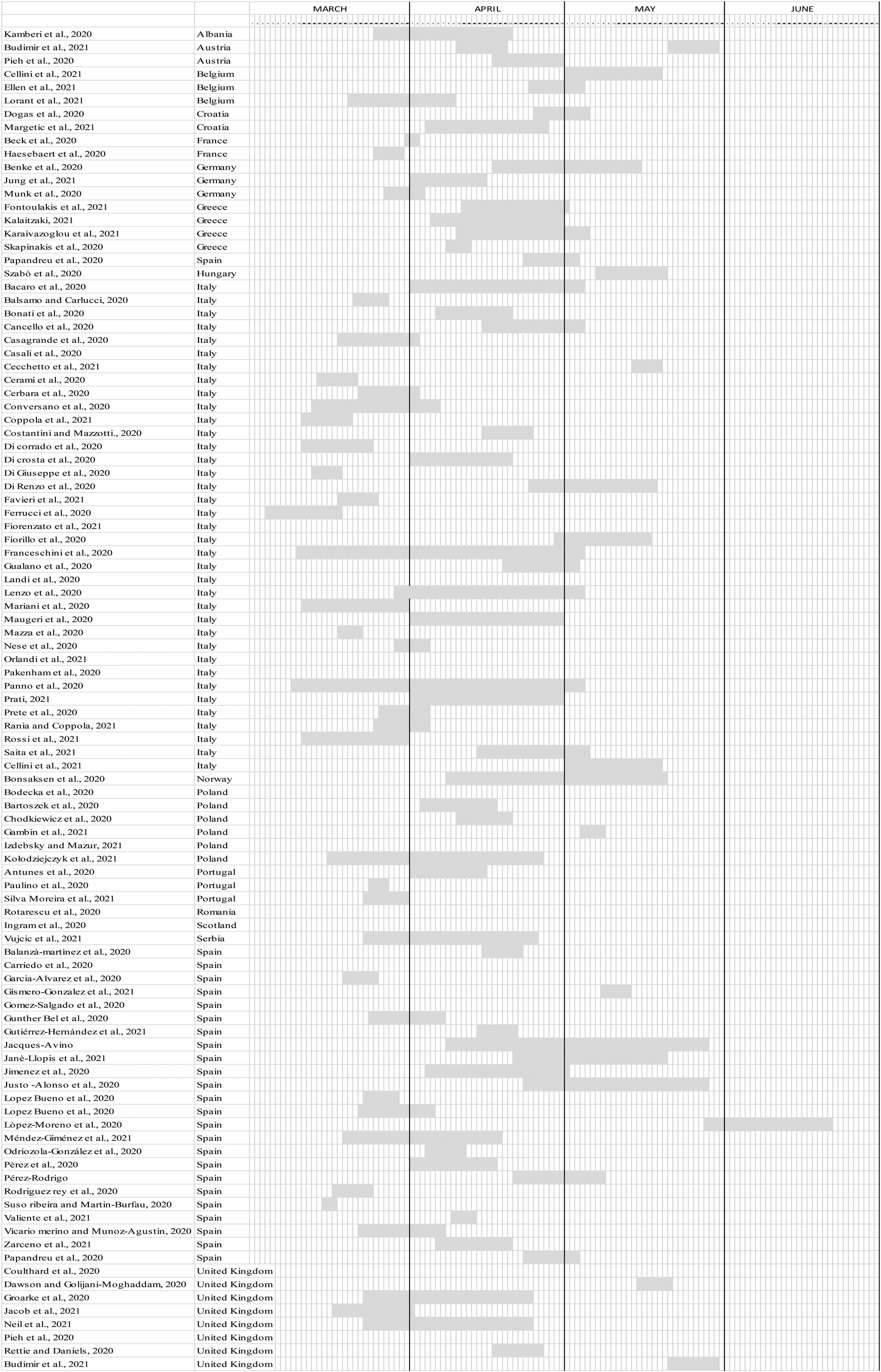

Some of the selected studies were conducted during the initial stages of the COVID-19 outbreak; it is therefore possible that they underestimated the actual occurrence of traumatic stress in the population, since delayed onset of symptoms, especially PTSD ones, is conceivable. Moreover, data collection time for cross-sectional studies (online Supplementary material, Fig. 4) differed also because decisions concerning time and type of quarantine differed between European countries.

Fig. 4. Timing of data collection for each European country.

The majority (98 out of 105) of the selected studies had a cross-sectional observational design, which does not allow one to establish cause and effect relationships and temporal association between variables, so these should be interpreted with caution. Time-limited, cross-sectional survey data shed little light on the enduring effects of quarantine, on how adaptations to quarantine changed or evolved over time, and on what happened during re-opening, when home-confinement restrictions began to ease. Only a few studies (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., Reference Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Idoiaga Mondragon, Dosil Santamaría and Picaza Gorrotxategi2020; Salfi et al., Reference Salfi, Lauriola, Amicucci, Corigliano, Viselli, Tempesta and Ferrara2020; Ausín et al., Reference Ausín, González-Sanguino, Castellanos and Muñoz2021; Cheval et al., Reference Cheval, Sivaramakrishnan, Maltagliati, Fessler, Forestier, Sarrazin, Orsholits, Chalabaev, Sander, Ntoumanis and Boisgontier2021; O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Wetherall, Cleare, McClelland, Melson, Niedzwiedz, O'Carroll, O'Connor, Platt, Scowcroft, Watson, Zortea, Ferguson and Robb2021; Velotti et al., Reference Velotti, Rogier, Beomonte Zobel, Castellano and Tambelli2021; Zavlis et al., Reference Zavlis, Butter, Bennett, Hartman, Hyland, Mason, McBride, Murphy, Gibson-Miller, Levita, Martinez, Shevlin, Stocks, Vallières and Bentall2021) analysed data at different time-points during the restrictive measures, in order to investigate the psychological impact caused by the pandemic longitudinally.

Considering that previous research on the long-term effects of pandemics and quarantining (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020) has shown that not only acute mental health effects occur, but that psychological distress may persist long after the crisis, it is essential to prioritise studies with longitudinal designs.

It is thus imperative to prospectively document the synergistic effects of multiple co-occurring risk factors, such as economic precarity, unemployment, isolation, uncertainty, loss, and fear, which may increase the likelihood of mental health difficulties. It is also important to highlight the fact that the effects of stress exposure may not manifest themselves immediately, but, in some individuals, may unfold over time (Wade et al., Reference Wade, Prime and Browne2020; Veldhius et al., Reference Veldhuis, Nesoff, McKowen, Rice, Ghoneima, Wootton, Papautsky, Arigo, Goldberg and Anderson2021).

Moreover, the processes that cultivate resilience change dynamically over time, and this supports the fact that the pandemic requires longitudinal analyses in order to monitor individual adaptation to uncertain conditions.

Only four studies (Szabó et al., Reference Szabó, Pukánszky and Kemény2020; Castellini et al., Reference Castellini, Rossi, Cassioli, Sanfilippo, Innocenti, Gironi, Silvestri, Voller and Ricca2021; Lorant et al., Reference Lorant, Smith, Van den Broeck and Nicaise2021; Ramiz et al., Reference Ramiz, Contrand, Rojas Castro, Dupuy, Lu, Sztal-Kutas and Lagarde2021) compared data collected during the pandemic's quarantine with the level of psychological status found in the general population under normal conditions.

Concerning the assessment tools, the majority of the studies used validated and reliable assessment instruments in order to investigate several domains of mental health and psychological wellbeing. Different assessment scales were used for population screening and different cut offs were employed by studies that used the same tests. The self-report questionnaires used in the majority of the studies were ‘the Patient Health Questionnaire’ (PHQ), used in 29 studies, and the GAD, used in 27 studies. Seven studies created ad hoc questionnaires (Cancello et al., Reference Cancello, Soranna, Zambra, Zambon and Invitti2020; Cerbara et al., Reference Cerbara, Ciancimino, Crescimbene, La Longa, Parsi, Tintori and Palomba2020; Di Corrado et al., Reference Di Corrado, Magnano, Muzii, Coco, Guarnera, De Lucia and Maldonato2020; Đogaš et al., Reference Đogaš, Lušić Kalcina, Pavlinac Dodig, Demirović, Madirazza, Valić and Pecotić2020; Ferrucci et al., Reference Ferrucci, Averna, Marino, Reitano, Ruggiero, Mameli, Dini, Poletti, Barbieri, Priori and Pravettoni2020; Nese et al., Reference Nese, Riboli, Brighetti, Sassi, Camela, Caselli, Sassaroli and Borlimi2022; Izdebski and Mazur, Reference Izdebski and Mazur2021). It must be noted that data collected relied on self-report measures related to psychological symptoms, and thus cannot be considered sufficient to formulate diagnoses of specific disorders.

The degree to which self-reported prevalence rates effectively represent common distress is still unknown, as well as to what extent this distress will result in increased rates of mental disorders and need for subsequent health treatment (Richter et al., Reference Richter, Riedel-Heller and Zuercher2021).

Although the symptomatology was assessed with widely used screening tools, scores should not be confused with a diagnosis, which can be assessed only by mental health professionals with additional assessment methods such as structured clinical interviews. It is important to note that the increase in psychological distress during quarantine is related to subjective perception and that there is a lack of pre-post pandemic analyses.

Another relevant aspect that should be considered is the possibility of selection bias related to the use of online surveys. The use of online surveys, and the snowball method for increasing participation, limit the generalisability of the results, although surveys currently represent the best methodological choice for data collection in a short time and in a pandemic situation. The convenient non-probabilistic nature of the chosen sample may not represent the countries' general populations: use of an online tool limits the participation of persons who do not use this type of technology, penalising, for example, elderly people or those living in socially disadvantaged contexts. Moreover, it was not possible to assess the participation rate since the number of subjects who received the link to the surveys was unknown.

A possible gender-related effect, which may not have been identified due to the small number of men who responded, should also be taken into consideration. More women than men participated in the studies, coherently with previous research, reaffirming that it is more difficult to recruit male participants (Korkeila et al., Reference Korkeila, Suominen, Ahvenainen, Ojanlatva, Rautava, Helenius and Koskenvuo2001; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Jordan, Lacey, Shapley and Jinks2004). Furthermore, variable distribution might differ between a sample and the population of reference for residence, age, sex, education and other characteristics, and this requires that study findings be generalised with caution.

Lastly, more than half of the studies enrolled Italian and Spanish populations: 40 studies collected data from Italy and 26 from Spain. This represents an unbalanced interest compared with other European countries, although the severity of COVID-19 in the two Mediterranean countries from the beginning of the pandemic can, in part, justify such a huge production. All the questionnaires were launched nation-wide but, at the time of data collection, the COVID-19 outbreak was more severe in some countries and in specific regions. This may have motivated more people living in those areas to fill in the questionnaires compared to residents from other regions. Moreover, COVID-19 has had different mortality rates worldwide, and the severity and frequency of mental health outcomes could be related to the intensity of the viral spread.

What can be done to mitigate the consequences of quarantine?

The current COVID-19 health emergency has completely changed the daily life of the population. Both the confinement scenario and the spread of the virus, as well as associated consequences, could alter people's cognitive and emotional state through perceived threat from the virus and through development of negative affective balance and feelings. Several individual, economic and psychological factors have also been found to play a role in the development of higher levels of symptomatology.

The pandemic has highlighted the need to pay greater attention to gender and to the private sphere to prevent, and alleviate, the psychological consequences of pandemic on more vulnerable groups.

Despite the limitations of the retrieved studies, justified in part by the need to rapidly to assess the situation as a whole, our results highlight the importance of identifying which groups may face more difficulties in adopting healthy behaviours (e.g. physical activity, healthy food choices and sleep routines) and maintaining physical and psychological wellbeing. By identifying vulnerable groups, intervention strategies may be more targeted, and the effectiveness of health strategies may be improved.

Maintaining regular habits during restrictive measures could be considered a protective factor for mental health outcomes. Encouraging healthy food choices, regular mealtimes and the carrying out of physical activity at home could therefore be a useful strategy to make the population aware of the need to remain healthy. The promotion of correct lifestyles is important for the protection of health, but it becomes even more important during periods of forced home confinement in reducing long-term negative effects of quarantine. Suggestions on how to maintain a correct lifestyle could be provided through video or app-based supports, but also through non-digital channels (such as TV, newspapers, journals, posters or leaflets) in order to reach less technology-oriented people.

Given that the most effective healthcare measure for reducing the incidence of the coronavirus pandemic was quarantine, and the fact that globalisation and travel increase the likelihood that a similar situation may occur in the future, knowledge of the emotional and cognitive effects of quarantine on the population could lead to the implementation of more effective measures aimed at facilitating coping strategies.

It is essential to implement psychoeducational programmes to manage the emotional and affective alterations caused by restrictive measures, especially if they are taken on a mass level and are repeated in time.

Conclusions

The implementation of forced restrictive measures to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 infection, in particular the more limiting ones such as quarantine, has influenced individual mental health. Depression, anxiety, psychological distress and post-traumatic symptoms have been the predominant, new-onset psychological health problems in European general populations during the pandemic. Several risk factors have been identified, such as being female, young, having a low income, being unemployed and having COVID-19-like symptoms.

Overall, despite the limitation of the studies, due also to the emergency pandemic situation, the results of this review suggest that there is an immediate psychological impact of the quarantine. Concerning the long-lasting effects, this impact may depend on each country's strategies and duration of restrictive measures taken. To mitigate the significant negative effects on emotional wellbeing, the adoption of appropriate strategies by health services is fundamental, as is preparing the general population for possible future waves of the pandemic. When applying quarantine measures, policy makers should attempt to find the right balance between reducing the risk of infection and minimising the risk of negative mental consequences, while also empowering wellbeing, especially in vulnerable groups.

Future research, based on longitudinal analyses, should attempt to monitor the increase in mental health symptoms over time, in particular their course after the end of the restrictive measures. It would also be important to investigate the social context-related factors that are likely to influence their relationship with quarantine.

Moreover, in addition to providing a focus on the most vulnerable populations, research should investigate between-country variations that result from the confluence of specific environmental stressors and time and type of quarantine in that given area.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000051

Availability of data and materials

The data are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Chiara Pandolfini for language editing and Daniela Miglio for editing.

Author contributions

G. S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from M.B. R.C. did the network analysis. M.B. critically revised the article and reviewed the final draft of the article. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The authors read and approved the final manuscript. M.B. is the guarantor.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix

Table A1. Keywords used for searching databases

Table A2. Critical appraisal of cross-sectional studies

Table A3. Critical appraisal of cohort studies